Abstract

This paper develops a methodological framework to review the literature relevant to the implications of social cohesion for entrepreneurs collaborating in the pursuit of innovation. The framework is then used to understand the current state of the art for that phenomenon. Thirdly, a theoretical model is developed for areas of concern in the stewardship of collaborating entrepreneurs. The abstracts of 631 academic resources between 1950 and 2020 are analyzed using Webster and Watson’s (MIS Quarterly, 26(2):xiii–xxiii, 2002) methodology. Sixty-four salient resources are identified and critically analyzed, categorizing research methodology, subject area, and additional, pertinent bibliometrics. Entrepreneurial collaboration is an emerging field of research that draws from a variety of disciplines and requires clarification in its use of terminology for both entrepreneurial collaboration and social cohesion. In addition to making those clarifications, the tendency of managers to maintain a hands-off approach in their oversight of entrepreneurial cadres is challenged. The theoretical model provides a useful overview of related concepts for future research and encourages managers to rethink their agency as necessary and not as a matter of interference. This paper contributes to the growing field of entrepreneurial collaboration by proposing the moderation of social cohesion as a means to sustain innovation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Firms seeking competitive advantage increasingly involve entrepreneurs defining and overcoming challenges (Carayannis et al., 2014, 2015). As entrepreneurial collaboration becomes more common in the pursuit of innovation, managers need a better understanding of how they can oversee these groups to sustain innovation without wasting finite organizational resources, principally time and money. The prevailing belief among managers is that interfering with the entrepreneurial process is likely to douse the very spark for the novel solutions they are seeking (Kempster & Cope, 2010; Stevenson & Jarillo, 2007). The uncertainty in managerial approaches to entrepreneurial collaboration is the motivation for this study.

Scholars agree that the very spark of innovation rests in the social bonds between individuals, referred to as social cohesion (Chan et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2017). Social cohesion must exist for synergy to develop, and synergy must be optimal for innovation to occur (Dundon, 2002; Witges & Scanlan, 2015). However, when social cohesion is excessive, innovation is unlikely (David et al., 2020; Quince, 2001; Schultz et al., 2016; Sulistyo & Ayuni, 2020; Wise, 2014). While the phenomenon of entrepreneurs working with one another is not new, studies do not explore how social cohesion moderation can optimize synergy. Therefore, this paper identifies a knowledge gap in understanding how managers can moderate social cohesion to foster sustainable innovation among collaborating entrepreneurs.

To explore the vast array of scholarly resources available in entrepreneurship, collaboration, social cohesion, organizational synergy, and related issues, the authors adopted the methodology of the structured approach described by Webster and Watson (2002). To select the source material for this systematic literature review, relevant thought leadership and major contributions were sought in leading journals, including prominent conference papers, dissertations, and published texts. This task was made possible using The University of Liverpool online library, which utilizes Discover library collections of print and online content to search a wide variety of content from, among other resources, journal articles, conference proceedings and reports, theses, and dissertations, as well as print and eBooks. Of particular focus were search results from EBSCO’s premier aggregated database in Academic Source Complete, Business Source Complete, JSTOR, Emerald, Elsevier, Wiley, Springer, Taylor & Francis, Sage, IEEE, WOS, and Scopus.

The methodological framework used in this study reveals active academic interest in social cohesion in the area of entrepreneurship and reveals an insufficient understanding of how social cohesion could be moderated to sustain innovation among collaborating entrepreneurs. Moreover, this study finds that managers cannot sit idly nor be self-assured that entrepreneurs will automatically, let alone sustainably, innovate. Managers must establish a collaborative agency in which they are seen as a resource by collaborating with entrepreneurs to support the development of interpersonal trust, sharing, and, most importantly, criticality. While providing a helpful overview for future researchers in locating and considering academic resources on the topic, this paper motivates new approaches to managerial intervention.

The next section of this paper is structured to analyze the methodology for conducting the literature review followed by analysis results. The authors then critically analyze and synthesize the selected academic resources’ insights concerning the identified concepts. The study’s conclusions and implications are presented at the end of the paper, closing with the authors’ thoughts on limitations and future research possibilities.

Methodology

Webster and Watson (2002) describe a selection process for peer-reviewed journal articles that is readily applicable to other forms of scholarly resources, such as conferences, doctoral theses, and published texts. This process allows the researcher to systematically eliminate vast numbers of scholarly resources that are not relevant as a first step (step 1). Examination of the references used in resources being considered comprised a backward search (step 2) as recommended by Webster and Watson (2002) as well as a forward search (step 3) to examine where and by whom selected papers had been cited. The preferred resource to expedite forward-searching was Google Scholar because of the ease of use and simplicity of the user interface compared to database utilities within Discover.

In step 1, approximately 4000 resources were gathered using keywords (entrepreneur*, collaboration, group cohesion, social cohesion, synergy, and innovation) and permutations using an asterisk (*) through the advanced search utilities within Discover and the databases listed above using Boolean as well as natural language searches. The selected keywords were based on the context of entrepreneurs collaborating in the pursuit of innovation. The asterisk was used to allow for wildcards. For example, “entrepreneur*” would allow searches to include various related words such as entrepreneur, entrepreneurs, entrepreneurial, and entrepreneurship. Step 1 was particularly helpful in supporting the efficiency of selecting scholarly resources even where varying definitions of particular terms returned inconsistent results. For example, entrepreneurial collaboration is not standardized to mean individual entrepreneurs working with one another to innovate. Many researchers use the term to describe instances of different entrepreneurial initiatives being melded as a matter of collaboration between firms.

The authors use this example to highlight the efficacy of a systematic literature review. Six hundred thirty-one academic resources were selected for further analysis and thirteen published texts, six dissertations and theses, and five conference papers. Of the peer-reviewed articles, 103 were found to be duplicates, while the other resources did not have duplicates in the searches conducted. Further selection scrutiny found 252 peer-reviewed articles to have irrelevant titles along with one prospective conference paper. One hundred eighty-eight peer-reviewed articles were rejected, along with two published texts, three dissertations, and one conference paper in the researcher’s review of abstracts and summaries. Finally, consideration of the full text reduced the number of peer-reviewed articles by forty-four. The selection process yielded sixty-one academic resources at the end of step 1. Step 2 identified one additional peer-reviewed article selected by backward searching. Finally, step 3 identified two additional peer-reviewed articles for a total of sixty-four resources as being of significant relevance. This process is summarized in Fig. 1 to illustrate the process of elimination undertaken by the authors and the process of elimination undertaken by the authors, and the identification of additional, relevant resources using backward- and forward-searching.

Using the concept matrix analysis, academic resources can be classified according to particular themes and traced to whether they are present or absent (Klopper et al., 2007). For example, in the context of social cohesion and how it might bear on collaboration among entrepreneurs, a general theme of limits and implications of social cohesion in entrepreneurs collaborating permits an efficient assembly of resources. Table 1 is formatted according to the year of publication for purposes of organization according to themes as emphasized by Webster and Watson (2002), not to undertake a chronological summary. Furthermore, this organization enables rigor in synthesizing state-of-the-art literature by avoiding the selection of resources that only support the authors’ bias or point of view (Klopper et al., 2007; MacLure et al., 2016).

In Table 1, the concept matrix for this study is summarized along with selected bibliometric data to orient the reader to the discussion and figures below. The authors’ intent in this section is to provide a “clear take-home message” for the reader regarding this study’s academic resources (Bem, 1995:p.172). Table 1 (concept matrix and selected bibliometrics) organizes the academic resources for this study in descending order by year and author(s). The key concepts identified in the above paragraph are then indicated using an “x” in the row associated with a given academic resource if that resource provides salient insight. Following the three steps of Webster and Watson (2002), five types of academic resources are used for this study: peer-reviewed journal articles (PRJA), academic texts or books (BOOK), expert opinions (EXPO)—namely, Harvard Business Review, conference or working papers (CONF), and doctoral theses (DOCT). The type of academic resource is also indicated in Table 1. The research methodology is noted as archival study (A), case study (C), survey (S), or theoretical (T). The country of publication for the academic resource is noted using ISO 3166 three-letter country codes. The SJR h-index (SCImago) is also noted in Table 1 unless it is either not applicable (N/A), such as in the case of most published scholarly books, or not listed (-), such as in the case of lowly cited journals. While several different indices exist to indicate the importance and prestige of journals, poorly cited journals are rapidly entering the indices, and researchers must have metrics that allow greater precision in distinguishing the prestige of a given journal (González-Pereira et al., 2010). While ideally, researchers would read each article and make their own judgments, they accept that not all resources or journals have the same value (Garfield, 2006; Guerrero-Bote & Moya-Anegón, 2012). This paper is not intended to debate the merits of the various indices available to distinguish journals’ prestige. The authors’ rationale for choosing the SJR h-index is methodological and technical. The SJR h-index establishes different values for citations according to the scientific influence of the journals that generate them. It resolves the computational issues for journals with no references to other journals in the database, unlike PageRank-based methods (González-Pereira et al., 2010). Finally, Table 1 lists the subject area and category listed for the given academic resource by SCImago (i.e., deriving from the Scopus database). Of course, this is not an exhaustive listing of the subject area and category descriptions that may exist for a given journal, but it allows the reader to develop a good sense of what domains contributed saliently to this study. The subject area and category descriptions are assigned arbitrary numbers corresponding to their alphabetical listing because of space constraints, as provided in Table 3.

Results

Bibliometric reporting is a helpful tool for researchers to share the lay of the land in a given field of research regarding where salient contributions and thought leadership are situated and disseminated. The authors pursued relevant literature identified using the methodology of Webster and Watson (2002) whereby concepts, not authors, determined the organizing framework allowing a fuller synthesis of salient insight. A given academic resource can report on more than one of the three themes traced in the concept matrix analysis shown in Table 1. The authors find that a fair representation of each theme is evident in the resources selected for this systematic literature review, as shown in Fig. 2 below. Within those sixty-four academic resources, thirty-five address limits and implications of social cohesion, 28 address dimensions of entrepreneurial collaboration, and 24 address effect and antecedents of organizational synergy.

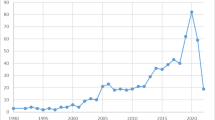

This study’s academic resources span 70 years from 1950 to 2020 and vary concerning the type of publication. Certainly, the concept of entrepreneurs collaborating is not new. However, the exacting knowledge of how the social cohesion of those entrepreneurs contributes to positive synergy and innovation is only gaining momentum since 2010. Table 2 summarizes the academic sources selected for this systematic literature review according to the type and year they were published.

The distribution of the type of academic resources selected using the methodological framework used in this study is represented by Fig. 3.

The selected sources show a clear majority of salient insight being held in peer-reviewed journal articles (PRJA) at 53%. Scholarly books comprise 35% of the academic resources informing this literature review, followed by conference papers at 6%, expert opinion (namely, the Harvard Business Review) at 3%, and doctoral theses at 3%. Figure 4 separates the type of academic resources selected by year.

While this general aggregation of the type of resource shown in Fig. 3 is helpful, the authors wish to provide the reader with a more detailed understanding of how scholarly books are increasingly being used to disseminate thought leadership in understanding entrepreneurial collaboration dimensions.

Based on the classification shown in Table 1, the methodologies of the academic resources used in this study are shown in Fig. 5.

Of the sixty-four academic resources selected for this study, 59% were archival, 22% were case studies, 16% were theoretical, and 3% used surveys. These resources are listed under 25 different subject areas or categories representing salient contributions from their respective domains. Table 3 summarizes the frequency of each of the subject areas or categories of the academic resources. The reader should bear in mind that several subject areas may be applicable to a given resource, which is the reason behind summarizing this information in Table 1 to have a convenient reference summary.

Unsurprisingly, the subject area of “Business, Management, and Accounting” is used to describe 19.3% of the salient resources while “Entrepreneurship” claims only 9.6%. Again, the methodological framework’s value is apparent as searching for insights into the entrepreneurial collaboration under the subject area of “Entrepreneurship” would have been disappointing in furthering the understanding of the implications of social cohesion in that phenomenon. Figure 6 helps to highlight the contributing subject areas for better emphasis to the reader.

Twenty-five subject areas and categories contribute to this study. However, the results of the literature review show 195 different keywords in the descriptions of the selected resources as compared to the six used in conducting the literature review itself (i.e., entrepreneur*, collaboration, group cohesion, social cohesion, synergy, and innovation). The authors generated a word cloud shown in Fig. 7 to represent the top 100 most frequent keywords in the results by showing the most frequent words in larger and more central print.

While this word cloud is a helpful visual tool to inform the reader about which keywords were more often associated with the results that provided salient insights, it also highlights the fact that the keywords used to conduct the search may not align perfectly with those in the results. For example, “social” is listed as part of twenty-four different keywords in the results (i.e., social aspects, social attitudes, social capital, social cohesion, social economy, social exclusion, social groups, social groups, social groups research, social inclusion, social integration, social loafing, social network topology, social networks—models, social order, social organization, social participation, social psychology, social psychology, social recognition, social relations, social responsibility, social structure, and social system).

The country of publication is an important consideration for understanding where relevant knowledge is being published and where it is likely to be disseminated. The country in which the academic resources for this study were published are listed in Table 4 and presented graphically in Fig. 8.

Knowledge about the country of publication can inform the researcher about the research output level for a given field. However, the country of publication is not necessarily the country where the researcher resides, let alone where the research was undertaken. For the resources used in this study, 6% were published in Canada, 25% in Germany, 15% in the UK of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, 2% in India, 2% in Mexico, 8% in the Netherlands, 2% in Poland, and 40% in the USA.

As discussed previously, the authors intend to provide a useful summary of the lay of the land concerning salient resources that contribute to furthering the understanding of the implications of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. In representing the prestige—or lack thereof—of the journals where academic resources used in this study were found, the authors selected the SJR h-index for its methodological and technological merits. Table 1 lists the SJR h-index rankings for the academic resources used in this study. Journals or resources that are not listed are indicated in Table 1 with a dash (-). Books are not typically ranked and are scored in Table 1 as N/A for not applicable. The journals that SCImago ranks are shown with their corresponding SJR h-index on March 31, 2021, in Fig. 9.

Of the twenty-six journals that are scored, Contaduría y Administración starts the list with an SJR h-index of 9, and the Annual Review of Psychology tops the list with a commendable SJR h-index of 230. The Harvard Business Review is well regarded as a magazine providing expert opinions despite not following a peer-review process and has an SJR h-index of 170, tied with the Journal of Business Venturing. Nevertheless, researchers must be vigilant to not fall victim to a bias of only consulting the highest-ranked journals. For example, “The Fifth Discipline” was written by Peter Senge in 1990 and is regarded as one of the twentieth century’s seminal business texts by the Harvard Business Review. This scholarly work is not ranked in the SJR h-index, yet it provides ground-breaking insight into navigating the social bonds central to this study’s key concepts. The academic resources used in this study represent a vast body of knowledge reflecting different research methodologies reported in scholarly resources that range from some of the most prestigious journals to those that are so infrequently cited that they are not ranked.

Concepts

Critically reviewing state of the art from the perspective of the major themes allows rigorous synthesis to critically examine the exploitation of social cohesion to optimize positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration and identify adaptations to managerial sensemaking in ascertaining the level of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. Using the themes defined in the concept matrix analysis (Webster & Watson, 2002, this analysis is divided into three sections:

-

1.

Dimensions of entrepreneurial collaboration

-

2.

Limits and implications of social cohesion

-

3.

Affects and antecedents of organizational synergy

Dimensions of Entrepreneurial Collaboration

A key point echoed by several researchers is that what is happening between the individual entrepreneurs has primacy over their mere proximity or bringing them together at an organizational level, especially because the structure with which they relate to one another may not be discernible to someone observing or judging their interactions externally (Corwin et al., 2012; Dundon, 2002; Quince, 2001; Stacey, 2011). Kempster and Cope (2010) and Stevenson and Jarillo (2007) find that managers overwhelmingly prefer to avoid interfering with entrepreneurs collaborating. However, others argue that managers must facilitate these interactions, but they do not explore the implications of social cohesion beyond noting its necessity for innovation to occur or its interference when excessive (David et al., 2020; Dundon, 2002; Larson & Starr, 1993; Quince, 2001; Sulistyo & Ayuni, 2020). Managers are not provided with direction on how to adapt their sensemaking to support entrepreneurial collaboration, let alone how their intervention could help optimize positive synergy. Chen et al. (2017), Schlaile and Ehrenberger (2016), Schultz et al. (2016), Stevenson and Jarillo (2007), and Quince (2001) agree that entrepreneurs are inventive in making changes through the introduction of new and novel ideas. However, Birley (1985) points out that entrepreneurs alone cannot be expected to sustainably generate actionable solutions without the benefit of others who also possess similar creative and innovative attributes and outlook, comprising a nurturing environment. Chen et al. (2017) further argue that by facilitating the social exchange of the individuals working jointly with one another, the synthesis of their diverse perspectives and collective intelligence becomes possible in the quest for innovation. Therefore, the authors argue for the standardization of the term entrepreneurial collaboration to mean the phenomenon of individual entrepreneurs working jointly to pursue innovation. Nearly half of the total number of resources rejected resulted from an inconsistency in using the term to mean collaborative entrepreneurship, even in recent thought leadership (cf. Berger & Kuckertz, 2016). Collaborative entrepreneurship describes entrepreneurial processes’ marshaling, especially in collaborations between (educational) institutions and private corporations. Quince (2001) is the significant, relevant scholarly resource that more often aligns with the authors’ use of entrepreneurial collaboration despite still using the term interchangeably with collaborative entrepreneurship.

As posited by Clar and Sautter (2014), organizational support of social exchange between entrepreneurs maximizes the conversion of market challenges into market opportunities. At the heart of this lofty expectation lies the possibility for collaborating entrepreneurs to achieve something greater than what they could achieve individually—synergy (Corwin et al., 2012), especially by focusing on joint development to motivate joint learning in the pursuit of concrete solutions (Clar & Sautter, 2014; Covi, 2016). Senge (1990) and Stacey (2011) emphasize that the need for firms to develop their capacity to innovate is not only a matter of key strategic advantage but also, as argued by McNish and Silcoff (2015), a matter of economic significance that ensures the survival of the firm. Consequently, organizations can certainly benefit from the inclusion of entrepreneurs, but they must oversee how such individuals can be engaged effectively, sustainably, and, of course, profitably (Dundon, 2002; Najmaei, 2016; Schlaile & Ehrenberger, 2016; Senge, 1990). Bringing entrepreneurs together can permit the participants to cooperate and construct solutions together, creating an opportunity and more critical decision-making (Chen et al., 2017; Sulistyo & Ayuni, 2020). As reported by McNish and Silcoff (2015), nothing is guaranteed, where the collaboration of entrepreneurs can be positive or negative with corresponding economic outcomes.

Scholars uniformly observe that entrepreneurs from within the firm, or externally, are increasingly brought together to face new challenges and to solve problems as organizations seek to bolster the key strategic advantage of innovation (Carayannis et al., 2014, 2015; Felden et al., 2016; Senge, 1990; Stacey, 2011). Birley (1985) adds that entrepreneurs’ inherently collaborative nature does not ensure innovation, especially when entrepreneurial participation is grafted onto existing organizational structures or processes. Furthermore, Kempster and Cope (2010) highlight entrepreneurs’ preference to own their own business rather than being employed. For the firm supporting entrepreneurial collaboration, several scholars concede that managers prefer to rely on entrepreneurs’ inherently collaborative nature, rather than risk interfering with their innovativeness (Bernard, 2000; Burgelman & Hitt, 2007; Koellinger, 2008; Stevenson & Jarillo, 2007). A further complication to the stewardship of entrepreneurial collaboration is the lack of positive associations that entrepreneurs tend to have with leadership in general, including as an aspiration for themselves (Kempster & Cope, 2010). In other words, the preference of entrepreneurs is neither to undertake a leadership role nor to be under an employer’s leadership per se (Kempster & Cope, 2010). This finding may seemingly validate managers’ appropriateness in keeping a hands-off approach to entrepreneurial collaboration but challenges any effort to balance the continued participation of members within entrepreneurial collaboration with any hope of sustained innovation (Dundon, 2002; Wong, 1992).

Therefore, if the justification for the engagement of entrepreneurs by any firm is to seek innovation as a matter of competitiveness and, in some cases, survival, as argued by McNish and Silcoff (2015), then the organizational resources (i.e., time and money) to support entrepreneurial collaboration must be allocated in a manner that can promote optimal organization synergy. Dundon (2002) pointed out that optimal synergy is necessary for innovation to occur in entrepreneurial collaboration and must not be left to serendipity, suggesting the need for managerial involvement. Interpersonal relationships are the very links where and through which entrepreneurs create innovation (Birley, 1985; Burgelman & Hitt, 2007; David et al., 2020; Larson & Starr, 1993; Najmaei, 2016). Tracing the knowledge held in the theme of entrepreneurial collaboration reveals a deficiency in how the aforementioned links could be exploited to optimize organizational synergy. The exploitation of these links, defined as social cohesion, is not described in the literature and constitutes the aim of this study to critically assess how social cohesion intervention could be used to optimize positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration.

Since “performance is the enduring result of innovation” (Carayannis et al., 2015:p.13) and the frank purpose of entrepreneurial engagement, necessitating managers to facilitate entrepreneurial collaboration is key to fostering greater innovative capacity (Carayannis et al., 2014, 2015). Accordingly, managers are advised to emphasize linking participants through interpersonal interaction to bolster their sense of belonging to the group comprising the entrepreneurial collaboration and should not fear triggering conflict as there is an inherent moderation of conflict in collaboration through which entrepreneurs become empowered to co-create innovation (Carayannis & Rakhmatullin, 2014; Quince, 2001). However, recommendations for the limits or nuance of that emphasis are not made beyond emphasizing the importance of creating access and interaction between the knowledge networks within the firm and external ones (Carayannis et al., 2015; Sulistyo & Ayuni, 2020).

Limits and Implications of Social Cohesion

The term social cohesion is increasingly claimed for use in the fields of economics and politics. The core of the phenomenon is not necessarily rooted in nationalist discourse because the sense of belonging anchors social relations towards the common good, resting in the interactions (Schiefer & Van der Noll, 2017). Group cohesion or social cohesion is the willingness of individuals to cooperate to survive and prosper with a sense of belonging, as defined by Dyaram and Kamalanabhan (2005). These terms are used interchangeably in the body of knowledge, with the preference in management science to use the term group cohesion to describe the concept. Literature about macroeconomics more often uses the term social cohesion. However, in so doing, economists and political scientists alike focus the concept of social cohesion broadly on the macro-level or nation-level interactions of innovative groups. However, compelling arguments exist to include micro-level social relationships of individual participants in consideration of social cohesion (Mulunga & Nazdanifarid, 2014). Mutuality and trust comprise the norms of the very social networks in which the links among individuals persist to support the use of social cohesion as the preferred term for intrinsic micro-level behavior (Berman & Phillips, 2004; Chan et al., 2006; Smith & Polanyi, 2008; Vveinhardt & Banikonyte, 2017). The very essence of entrepreneurship is embedded in those linkages (Najmaei, 2016). Carron (1982) regards social cohesion as establishing social bonds that potentiate the group’s persistence in a unified fashion by the participants. Some scholars suggest the concept is best defined as “a dynamic process that is reflected in a tendency for a group to stick together and remain united in the pursuit of its goals and objectives” (Carron, 1982:p.124; Mudrack, 1989a, b). The notion of fondness is also considered in the literature, but not accepted in any universal fashion because the management context is more concerned with the performativity of the members of the group in accomplishing an assigned task than the sociability of the group members with one another (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009; Mudrack, 1989a, b).

According to Barile et al. (2018) and Forsyth (2010), theorists decry the fact that cohesiveness is used to describe a vast array of group interactions and group functionality such that the concept itself lacks cohesion. This issue highlights the persistent deficiency within the body of knowledge concerning the discourse between the operational and conceptual definitions of cohesiveness (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009; Quince, 2001). Theorists and managers alike conflate the term group cohesion with task cohesion, which focuses principally on the group’s performance as it relates to the coordination of the motivations and skills of the members of the group (Casey-Campbell & Martens, 2009; Mudrack, 1989a, b). Mudrack (1989a) argues that despite decades of research on the topic of cohesiveness, the body of knowledge remains “dominated by confusion, inconsistency, and almost inexcusable sloppiness about defining the construct” (p. 45). Moreover, while the attraction between the individuals of the group is not a matter of mere fondness, the attraction between individuals to form a group together is the essence of social attraction which, when intensified, can permeate the entire group and transform the individuals from being conjoined to being cohesive (Barile et al., 2018; Forsyth, 2010; Mudrack, 1989a). The economic benefit of entrepreneurial collaboration is embedded in the strength and appeal of the social relationship between the entrepreneurs working jointly (David et al., 2020; Quince, 2001; Sulistyo & Ayuni, 2020). The primacy of social cohesion in the pursuit of innovation through entrepreneurial collaboration is highlighted without further direction on how moderating social cohesion could help sustain positive synergy. Here, the authors assert their preference for the use of social cohesion instead of group cohesion in the context of entrepreneurial collaboration, especially in the context of global enterprise where tasks may vary or lack clear definition. Therefore, to recruit and assemble diverse entrepreneurial individuals, task cohesion cannot be considered a priori primacy over social cohesion in fostering the innovative potential of individual entrepreneurs. This consideration returns the authors’ curiosity to consider managerial adaptations through sensemaking of social cohesion towards supporting organizational synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration.

People develop links between one another and their group as a whole, whether they are brought together for social interactions or a particular task, creating a sense of belonging (Hoigaard et al., 2006). Despite an ever-evolving definition of social cohesion, the notion of a sense of belonging is central to its understanding and rests in the interpersonal bonds between members of the group (Chan et al., 2006; Chen et al., 2017). Some scholars have declared social cohesion as “the total field of forces which act on members to remain in the group” (Festinger et al., 1950: p.164) because it is exceptionally challenging to quantify in empirical research (Chan et al., 2006). Social cohesion bears on individual and organizational bonds comprising social processes where the sense of belonging remains the dominant characteristic (Reitz & Banerjee, 2005). In a management context, social cohesion is multi-faceted but widely accepted as a hinging on the sense of belonging valued by any group member through their interpersonal relationships. It drives their willingness to work jointly, arising from individuals’ collaboration fuelled by their level of mutual admiration in creating a heightened sense of belonging (Dyaram & Kamalanabhan, 2005; Forsyth, 2010). Despite the consensus regarding social cohesion as a sense of belonging, the literature does not report how it might be exploited to optimize positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration. There are limits to social cohesion on which organizational survival hinges (Berger, 2018). Without social cohesion, members of a group will leave (member exit), disintegrating the group such that it would no longer exist (Dion, 2000). However, with social cohesion, members of a group increase their participation with much less risk of member exit (Dyaram & Kamalanabhan, 2005; Wong, 1992). The key concern from a managerial perspective arises when group members face new problems and must adapt collectively in creating new solutions by performing together in a manner that exceeds their capabilities (i.e., positive synergy). Such performance is an antecedent to innovativeness (Dundon, 2002). If entrepreneurs are to co-evolve with market challenges, they require involvement and interaction towards a sense of belonging that values cooperation and knowledge in supporting innovation (Covi, 2016). Therefore, a managerial decision to trust in a socially cohesive entrepreneurial collaboration’s innovative capabilities may prove erroneous.

The exact role of social cohesion in fostering innovativeness ranges from finding a direct and positive relationship (Wong, 1992) to the finding that the relationship diminishes when social cohesion is excessive (Stewart et al., 2008; Wise, 2014). However, social cohesion may be more likely to have a moderating effect on innovativeness. A better understanding of how social cohesion bears upon innovativeness in entrepreneurial collaboration is valuable to organizations that seek to integrate entrepreneurial cadres into their firms’ culture. This discussion gives rise to the first research question of this study, RQ1 (How can social cohesion intervention be used in entrepreneurial collaboration to optimize positive organizational synergy?).

Managerial sensemaking must adapt to recognize when synergy among collaborating entrepreneurs is inadequate, optimal, or excessive. Social cohesion rests in the interpersonal relationships within entrepreneurial collaboration and entrepreneurship itself (Berger & Kuckertz, 2016; Dundon, 2002; Hoigaard et al., 2006). Social cohesion does influence organizational synergy; it does not always do so in a manner that contributes positively to collective performance or problem-solving capacity, especially in highly socially cohesive groups where the ability to innovate in the face of new challenges stalls (Griffith et al., 2015; Hoigaard et al., 2013; Sethi et al., 2001; Wise, 2014). A pragmatic manager may be reluctant to sacrifice satisfactory functionality for innovative capacity that may or may not be necessary for some time. This conundrum further supports the need to inquire into how social cohesion intervention can optimize positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration. Accordingly, this discussion gives rise to the second research question for this study, RQ2 (How should managers adapt their sensemaking of social cohesion to support positive organizational synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration?).

Social cohesion has been identified as the site of innovativeness and economic impact in entrepreneurial collaboration and, therefore, merits consideration of the possibility of its measurement. Identifying an appropriate instrument supports the furtherance of understanding how managers can adapt their sensemaking of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. The sociometric technique is a qualitative, descriptive instrument that has been in use for more than half a century and allows the measurement of what is happening in a group in terms of social cohesion, although this procedure is unable to answer why individuals have formed linkages (Forsyth, 2010). The sociometric technique in research about social cohesion in entrepreneurial environments is a valid and persistent practice (Barile et al., 2018). The sociometric test is a drawing undertaken by the subject to represent the structure of social relationships among the members of a group in a particular time reference. This drawing reflects perceptions of rejection and leadership within the group. This technique is widely used in education and has been a useful indicator of social cohesion, especially useful for small groups (Barile et al., 2018). The criticism of the sociometric technique arises from the reliance of one individual rating others and representing a very general indication of the linkages between group members (ibid). However, to consider the implications of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration, the sociometric technique is entirely appropriate. It provides a means of gauging social cohesion among collaborating entrepreneurs that is situated in their perspective. Moreover, confronting the strength of interaction through social cohesion evaluation can support collaboration because the self-assessment of strengths and interactions is key to innovating and learning collaboratively (Clar & Sautter, 2014).

The utilization of internal observations such as sociometric technique or external observations such as proximity tags or advanced audio–video analysis is a matter of fervent debate in the literature because new, interesting models shall develop that help both researchers and practitioners to differentiate between the internal and external perceptions of a group through the use of automatically extracted cues (Barile et al., 2018; Hung & Gatica-Perez, 2010). Proximity tags track the time an individual spends with or near another member of the group. This technique cannot provide any further insight into how such proximity impacts the quality versus the strength of linkages towards optimizing the group’s collective performance. Collaborating entrepreneurs with high levels of social cohesion may consider themselves to have a high level of performativity. However, external observation may reveal inefficiency owing to excessive time being utilized to strengthen their social bonds rather than collaborating on a solution for the problem at hand (Hung & Gatica-Perez, 2010; Stewart et al., 2008; Wise, 2014; Wong, 1992). Regardless, the optimization of organizational synergy hinges on the quality—not just the strength—of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration.

Affects and Antecedents of Organizational Synergy

Synergy refers across disciplines to the whole being greater than the sum of its parts. The term, however, did not arise in management sciences but in the field of physiology in the mid-nineteenth century, where it was used to address the notion of a collective evolutionary drive in a sociological context (Werth, 2002). It was considered the universal constructive principle of nature enhancing cooperative output (Ward, 1918). Whether further extended into politics or business, the implication that such cooperative output is always positive is challenged (Frigotto, 2016; Goold & Campbell, 1998; Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013). In the management context, synergy refers to the individual people and their related knowledge, abilities, and processes merging to expand the firm’s capabilities, especially in the face of new challenges and problems (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Lawford, 2003). Tracing the theme of limits and implications of social cohesion establishes social cohesion as the antecedent to organizational synergy and the site where the potential for economic impact and the innovativeness attributed to entrepreneurs resides. Without the linkages that comprise social cohesion, organizational synergy would not be possible (Lawford, 2003; Najmaei, 2016; Oketch, 2004; Wise, 2014). In the case of entrepreneurial collaboration, the driving force behind bringing entrepreneurs together is the pursuit of innovation, for which meaningful organizational synergy must occur (Camuffo & Gerli, 2016; Dundon, 2002; Lawford, 2003; Liening et al., 2016). While organizational synergy may be present to some degree, demonstrably enhancing the collective abilities of group participants, it can be suboptimal or even negative due to diminished critical thinking and decision-making reducing the capability to innovate (Dundon, 2002; Goold & Campbell, 1998; Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Lerner et al., 2015).

Managers can bolster synergy through the micro-level interactions of participants by the quality of events they organize to promote success in problem-solving or other collaborative activities (Vveinhardt & Banikonyte, 2017). As individuals perceive themselves to be successful in their desire to contribute increased, enhancing the participants’ quality of interconnectedness. The challenge remains in how to effectively moderate social cohesion so that it does not become excessive. Managers of entrepreneurial collaboration must foster social cohesion, but they must be vigilant for evidence of its excess manifesting as wasteful negative synergy (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Wise, 2014). Principally, organizational synergy is believed to be reflected in the efficiency by which a given team or group can accomplish their task (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Kempster & Cope, 2010; Lawford, 2003; Namjoofard, 2014; Wise, 2014). This perspective may be significant and helpful in assessing the team’s performance through their output for a given task. However, such an approach overlooks the need to consider the sustainability of the underlying strategic advantage being cultivated, which is the organization’s innovative capacity. While it is important for any supporter or manager of entrepreneurial collaboration to recognize when organizational synergy is occurring, it is perhaps even more important for such stakeholders to recognize what is not reflective or indicative of organizational synergy (Goold & Campbell, 1998). In highly socially cohesive groups, suboptimal synergy is characterized by concurrence seeking, known as groupthink. This diminishes the consideration of alternative solutions and criticality because of the desire of individual members to maintain harmony, thereby constraining the generation of new ideas or novel applications of existing solutions, even among entrepreneurs (Fox, 2019; Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Janis, 1973; Wise, 2014). However, individuals in a highly socially cohesive group can also aggregate and polarize within the group, becoming increasingly entrenched in a particular point of view and less willing to consider alternative solutions (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013). The diminished consideration of alternative solutions can be further exacerbated in highly socially cohesive groups by a willingness to make riskier decisions than those that would have been taken by any individual member (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013).

Therefore, in the pursuit of positive synergy, managers cannot overlook the perils of excessive social cohesion. The need to better understand the risks to organizational synergy from leveraging social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration arises must also be addressed. The literature shows that entrepreneurial collaboration engagement by organizations striving for global competitiveness is left ambiguous because models of organizational synergy rely heavily upon organizational commitment and leadership. This tendency is ill-suited to collaborating entrepreneurs who are typically not employees and are averse to positional leadership, especially as a personal aspiration in the pursuit of innovation (Dickel & Graeff, 2016; Frigotto, 2016; Kempster & Cope, 2010; Oketch, 2004; Namjoofard, 2014; Wong, 1992). Compared to conventional hierarchical organizational structures that employ conventional worker archetypes, understanding how social cohesion can be exploited to optimize positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration is necessary to avoid wasting organizational resources, especially time and money. But the relentless pursuit of synergy by managers frequently leads to a bias that overemphasizes social cohesion without realizing that the result can lead to positive (or optimal) as well as negative (or suboptimal) synergy (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Lawford, 2003; Witges & Scanlan, 2015). Striving for organizational synergy very often results in a synergy bias which means that managers or even more powerful organizational actors overestimate the benefits of what they believe to be reflective of organizational synergy and underestimate the organizational cost in terms of time and money in that pursuit (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Lawford, 2003). Again, the need to address how managers should adapt their sensemaking of social cohesion to support positive synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration arises but is not addressed in the literature.

Furthermore, suboptimal synergy occurs in highly socially cohesive groups in the form of counteracting measures being taken by individuals to decrease the capabilities, criticality, and decision-making of the group rather than increase them beyond the sum of abilities of individual members of the group (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Janis, 1973). In such an occurrence, a manager could easily misread the proximity and time being spent by individuals interacting as evidence of positive organizational synergy. Of great interest to the overseers of teamwork, especially in the case of entrepreneurial collaboration, is the fact that positive synergy represents an optimal state which improves the utilization of resources which could extend not only to the time and money the organization is allocating for entrepreneurial collaboration but any other organizational resource, such as the utilization of technology assets (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Lawford, 2003). Negative or suboptimal synergy manifests not only in reduced efficiency of operations but very often with decreased quality alongside underutilization of resources with the potential to increase organizational cost and contribute to the underestimation of cost by managers should they succumb to synergy bias (Goold & Campbell, 1998; Lawford, 2003). Perhaps the most significant indicator of suboptimal or negative organizational synergy is disequilibrium with the external environment (Lawford, 2003). These issues are of considerable value in addressing and validating the need to consider the risks to organizational synergy from leveraging social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. The synthesis of the selected literature traced through the theme of effects and antecedents of organizational synergy reveals that any framework to optimize entrepreneurial collaboration’s innovativeness must include conceptualizing moderating suboptimal synergy moderating social cohesion.

As managers observe an increase in group members’ communication and interactions, they can be misled to presume that the underlying increase in social cohesion will strengthen mutually positive attitudes between individuals and the rest of the group (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013). Of course, this issue demands an improved understanding of how and to what extent managers should adapt their sensemaking of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. Concerning any teamwork or managerial effort, organizational synergy reflects the combined effort of the team’s members but the condition of positive or optimal organizational synergy towards creative problem-solving. Innovation cannot be achieved until the individual members interact with a greater joint effect than the sum of those acting alone (Huczynski & Buchanan, 2013; Lawford, 2003). As Lawford (2003) argues, organizational synergy can be positive or negative where positive synergy has beneficial, contributory, and productive effects, allowing for improved efficiency and greater exploitation of those opportunities available to or created by the organization. While most managerial interventions are satisficed to deliver required or even increased productivity, such an outcome does not necessarily require optimal organizational synergy. In facing new problems, the entrepreneurial cadre must function in a state of positive synergy to optimize the likelihood of successful innovation (Dundon, 2002; Felden et al., 2016; Najmaei, 2016; Wise, 2014). Furthermore, in the case of excessive social cohesion, the group’s performance may be satisfactory without being able to outperform the abilities of the individual members because known sustainably, counterproductive phenomena arise as pointed out by Huczynski and Buchanan (2013).

Positive organizational synergy will most often lead to more efficient use of existing organizational resources, while negative organizational synergy will not. This point remains theoretical without further probing of the selected literature to explore how such an observation can translate to meaningful intervention while important to be included in any managerial sensemaking efforts. Here, an important point synthesized from the tracing of effects and antecedents of organizational synergy through the scholarly resources selected for this structured literature review is that social cohesion is not a by-product or meta-phenomenon of organizational synergy; rather, the opposite is true. Therefore, if organizational synergy is to be fostered from a managerial perspective, social cohesion must be moderated to ensure that the quality of the very linkages that potentiate the economic benefit and innovativeness of entrepreneurial collaboration is given primacy over the strength of those linkages.

Theoretical Model

The consensus among scholars regarding the related concepts in entrepreneurial collaboration is that social cohesion must exist for the entrepreneurial cadre to exist in any effective way. If the synergy in that group is suboptimal because of excessive social cohesion, valuable organizational resources, including time, money, and technological assets, will be squandered, and the quality of decision-making will diminish. If the synergy in that group is optimal because of just the right amount of social cohesion, then innovation is much more likely to occur. The authors’ propose the following theoretical model (Fig. 10) based on the results of this study to represent the relationship between social cohesion, moderation, entrepreneurial collaboration, and synergy. In doing so, the authors’ intended to encourage other researchers to focus on these key areas. The authors provoke them to rethink their tendency to maintain a hands-off approach to oversee entrepreneurs’ oversight for managers.

This theoretical model should alert the reader that future research directions should continue to address the gap revealed in this study: the current understanding of how social cohesion could be moderated to sustain innovation among collaborating entrepreneurs is insufficient. As modern firms increasingly add entrepreneurial collaboration in the pursuit of competitive advantage, scholars and managers must further understand how to engage with the entrepreneurs that are being asked to provide novel solutions. The challenge lies in understanding how to increase interpersonal trust, sharing, and, most importantly, criticality in entrepreneurial cadres without causing member exit.

Conclusion and Implications

This systematic literature review demonstrates consensus that social cohesion is antecedent to synergy. Moreover, optimal synergy is necessary for successful innovation in entrepreneurial collaboration. These findings are significant in fulfilling the first objective of this study to critically examine social cohesion’s exploitation to optimize positive organizational synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration. This study’s findings also provide insight for RQ1 (How can social cohesion intervention be used in entrepreneurial collaboration to optimize positive organizational synergy?) insofar as validating the notion to explore the moderation of social cohesion as a means of sustaining optimal synergy as an active area for future research. Social cohesion is validated as the site for intervention. What particular activities might reliably and cost-effectively deliver sustainable optimal synergy by moderating social cohesion are not revealed in the academic resources analyzed in this study. However, this creates a significant opportunity for experimentation and future research.

The addition of entrepreneurial collaboration to bolster problem-solving capacity is an option for organizations seeking a competitive advantage and an increasingly recommended inclusion to modern firms’ organizational structures.

Several clarifications in terminology become possible and necessary in analyzing the selected academic resources in the context of this study:

-

1.

The authors argue that the term entrepreneurial collaboration be standardized to refer to the phenomenon of individual entrepreneurs working jointly to pursue innovation.

-

2.

Optimal synergy and positive synergy are used interchangeably to mean that the collaborating entrepreneurs function with a problem-solving capacity over their abilities or contributions.

-

3.

Suboptimal synergy can be the result of insufficient as well as excessive social cohesion. When social cohesion is insufficient or too low, the entrepreneurial collaboration can disintegrate through member exit. When social cohesion is excessive, this study confirms that groupthink, and polarization can occur, leading to resistance to alternate solutions and unnecessarily risky choices.

This systematic literature review is partly fulfilled; the second objective is to identify some adaptations to managerial sensemaking in ascertaining the level of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration. Managers are well served to watch for evidence of suboptimal synergy, as discussed above. Whatever intervention may be used to mitigate excessive social cohesion, managers cannot assume their actions would only support optimal synergy. It is possible that maladroit intervention could diminish social cohesion drastically, making it necessary to consider member exit as a possible consequence. In addressing RQ2 (How should managers adapt their sensemaking of social cohesion to support positive organizational synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration?), the authors acknowledge that further sensemaking adaptations would support more effective stewardship of entrepreneurial collaboration. Those sensemaking adaptations would benefit significantly from triangulating the level of social cohesion within the entrepreneurial collaboration by incorporating data from external observation technologies alongside sociometric testing.

Therefore, this study contributes new knowledge by demonstrating that the moderation of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration is possible and an important research direction and necessary for modern firms pursuing innovation. This paper’s most significant results provide an overview for researchers interested in this area along with a theoretical model that highlights areas of key concern. The authors draw attention to the relationships of key concern areas, encouraging further exploration by researchers and inclusion in managers’ agency and sensemaking efforts.

Limitations

Systematic literature reviews provide an excellent tool to inform practice development (Rees & Ebrahim, 2001). The authors consciously selected academic resources according to identified themes and research quality as opposed to the agreement with their opinions. This safeguards the systematic literature review from becoming a summary of a particular viewpoint or a particular author (Webster & Watson, 2002). However, the selection of academic resources can never be completely free of the authors’ biases despite the wide variety of databases used in this study (Kraus et al., 2020).

Future Research

This literature review shows that the implications of social cohesion in entrepreneurial collaboration are a fledgling area of research. The body of knowledge does not offer specific guidance for managerial intervention. The strategies to successfully maintain adequate social cohesion and prevent member exit must be balanced with those strategies that mitigate excessive social cohesion and prevent wasteful negative synergy. The methods by which managers can access entrepreneurial cadres’ internal dynamics will be supplemented by newer external technologies, including proximity tags and advanced audio–video analysis. By studying various techniques, rigorous research will someday be able to accurately ascertain the level of social cohesion in an entrepreneurial cadre and help managers maintain optimal synergy in entrepreneurial collaboration. Research must also evaluate the design of interventions to moderate social cohesion in terms of the appropriate allocation of organizational resources, including time, money, usage of technological assets, etc.

References

Barile, S., Riolli, L., & Hysa, X. (2018). Modelling and measuring group cohesiveness with consonance: Intertwining the Sociometric Test with the Picture Apperception Value Test. Systems Research and Behavioral Science, 35(1), 1–21.

Bem, D. J. (1995). Writing articles for Psychological Bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 172–177.

Berger, P. L. (2018). The limits of social cohesion: Conflict and mediation in pluralist societies. Routledge.

Berger, E. S., & Kuckertz, A. (2016). Female entrepreneurship in startup ecosystems worldwide. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 5163–5168.

Berman, Y., & Phillips, D. (2004). Indicators for social cohesion. European Foundation on Social Quality, Amsterdam.

Bernard, P. (2000). Social cohesion: A dialectical critique of a quasi-concept. Strategic research and analysis directorate, Department of Canadian Heritage, Paper SRA-491.

Birley, S. (1985). The role of networks in entrepreneurial process. Journal of Business Venturing, 1, 107–117.

Burgelman, R. A., & Hitt, M. A. (2007). Entrepreneurial actions, innovation, and appropriability. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 1(3–4), 349–352.

Camuffo, A., & Gerli, F. (2016). The complex determinants of financial results in a lean transformation process: The case of Italian SMEs. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in Entrepreneurship, Innovation and Technology Research – Applications of Emergent and Neglected Methods (pp. 309–330). Springer Nature.

Carayannis, E. G., Grigoroudis, E., Sindakis, S., & Walter, C. (2014). Business model innovation as antecedent of sustainable enterprise excellence and resilience. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5(3), 440–463.

Carayannis, E. G., & Rakhmatullin, R. (2014). The Quadruple/quintuple innovation helixes and smart specialization strategies for sustainable and inclusive growth in Europe and beyond. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5(2), 212–239.

Carayannis, E. G., Samara, E. T., & Bakouros, Y. L. (2015). Innovation and entrepreneurship: Theory, policy and practice. Springer.

Carron, A. V. (1982). Cohesiveness in sport groups: Implications and considerations. Journal of Sport Psychology, 4, 123–138.

Carron, A. V., Colman, M. M., Wheeler, J., & Stevens, D. (2002). Cohesion and performance in sport: A meta analysis. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 24(2), 168–188.

Casey-Campbell, M., & Martens, M. L. (2009). Sticking it all together: A critical assessment of the group cohesion–performance literature. International Journal of Management Reviews, 11(2), 223–246.

Chan, J., To, H. P., & Chan, E. (2006). Reconsidering social cohesion: Developing a definition and analytical framework for empirical research. Social Indicators Research, 75(2), 273–302.

Chen, M. H., Chang, Y. Y., & Chang, Y. C. (2017). The trinity of entrepreneurial team dynamics: Cognition, conflicts and cohesion. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 23(6), 934–951.

Clar, G., & Sautter, B. (2014). Research driven clusters at the heart of (trans-)regional learning and priority-setting processes. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 5(1), 156–180.

Corwin, L., Corbin, J. H., & Mittelmark, M. B. (2012). Producing synergy in collaborations: A successful hospital innovation. The Innovation Journal, 17(1), 1–16.

Covi, G. (2016). Local systems’ strategies copying [sic] with globalization: Collective local entrepreneurship. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 7(2), 513–525.

David, K. G., Yang, W., Bianca, E. M., & Getele, G. K. (2020). Empirical research on the role of internal social capital upon the innovation performance of cooperative firms. Human Systems Management, 1–15.

Dickel, P., & Graeff, P. (2016). Applying factorial surveys for analyzing complex, morally challenging and sensitive topics in entrepreneurial research: The case of entrepreneurial ethics. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 199–218). Springer Nature.

Dion, K. L. (2000). Group cohesion: From” field of forces” to multidimensional construct. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 4(1), 7–26.

Dundon, E. (2002). The seeds of innovation: Cultivating the synergy that fosters new ideas. Amacom.

Dyaram, L., & Kamalanabhan, T. J. (2005). Unearthed: The other side of group cohesiveness. Journal of Social Sciences, 10(3), 185–190.

Felden, B., Fischer, P., Graffus, M., & Marwede, L. (2016). Illustrating complexity in the brand management of family firms. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 219–244). Springer Nature.

Festinger, L., Schachter, S., & Back, K. (1950). Social pressures in informal groups: A study of human factors in housing. In: Festinger, L., Schachter, S. & Back, K. (eds.) Social Pressure in Informal Groups, Chapter 4. Cambridge, Massachusetts, MIT Press.

Forsyth, D. R. (2010). Group Dynamics (5th ed.). California, Wadsworth.

Fox, S. (2019). Addressing the influence of groupthink during ideation concerned with new applications of technology in society. Technology in Society, 57, 86–94.

Frigotto, M. L. (2016). Effectuation and the think-aloud method for investigating entrepreneurial decision making. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 183–198). Springer Nature.

Garfield, E. (2006). The history and meaning of the journal impact factor. JAMA, 295(1), 90–93.

González-Pereira, B., Guerrero-Bote, V. P., & Moya-Anegón, F. (2010). A new approach to the metric of journals’ scientific prestige: The SJR indicator. Journal of Informetrics, 4(3), 379–391.

Goold, M., & Campbell, A. (1998). Desperately seeking synergy. Harvard Business Review, 76(5), 130–143.

Griffith, R. L., Sudduth, M. M., Flett, A., & Skiba, T. S. (2015). Looking forward: Meeting the global need for leaders through guided mindfulness. In: Wildman, J.L and Griffith, R.L. (eds.), Leading Global Teams, New York, Springer, pp.325–342.

Guerrero-Bote, V. P., & Moya-Anegón, F. (2012). A further step forward in measuring journals’ scientific prestige: The SJR2 indicator. Journal of Informetrics, 6(4), 674–688.

Hoigaard, R., Boen, F., De Cuyper, B., & Peters, D. M. (2013). Team identification reduces social loafing and promotes social laboring in cycling. International Journal of Applied Sports Science, 25(1), 33–40.

Hoigaard, R., Säfvenbom, R., & Tonnessen, F. E. (2006). The relationship between group cohesion, group norms, and perceived social loafing in soccer teams. Small Group Research, 37(3), 217–232.

Huczynski, A. A., & Buchanan, D. A. (2013). Organizational behaviour. Pearson.

Hung, H., & Gatica-Perez, D. (2010). Estimating cohesion in small groups using audio-visual nonverbal behavior. IEEE Transactions on Multimedia, 12(6), 563–575.

Janis, I. L. (1973). Groupthink and group dynamics: A social psychological analysis of defective policy decisions. Policy Studies Journal, 2(1), 19–25.

Kempster, S., & Cope, J. (2010). Entrepreneurs’ and managers’ leadership roles compared: Context is what matters: What a person does trumps who they are. Development and Learning in Organizations: An International Journal, 24(4), 30–32.

Klopper, R., Lubbe, S., & Rugbeer, H. (2007). The matrix method of literature review. Alternation, 14(1), 262–276.

Koellinger, P. (2008). Why are some entrepreneurs more innovative than others? Small Business Economics, 31(1), 21–37.

Kraus, S., Breier, M., & Dasí-Rodríguez, S. (2020). The art of crafting a systematic literature review in entrepreneurship research. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 16(3), 1023–1042.

Larson, A., & Starr, J. A. (1993). A Network Model of Organization Formation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 17(2), 5–15.

Lawford, G. R. (2003). Beyond success: Achieving synergy in teamwork. The Journal for Quality and Participation, 26(3), 23–27.

Leavitt, H. J. (1974). Suppose we took groups seriously... Prepared for Western Electrics Symposium on the Hawthorne Studies. [Online] Available from: http://www.eric.ed.gov/contentdelivery/servlet/ERICServlet?accno=ED103291Accessed 2 Feb 2017.

Lerner, J., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. (2015). Emotion and decision making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66, 799–823.

Liening, A., Geiger, J., Kriedel, R., & Wagner, W. (2016). Complexity and entrepreneurship: Modeling the process of entrepreneurship education with the theory of synergetics. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 93–116). Springer Nature.

MacLure, K., Paudyal, V., & Stewart, D. (2016). Reviewing the literature, how systematic is systematic? International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy, 38(3), 685–694.

McNish, J., & Silcoff, S. (2015). Losing the signal: The untold story behind the extraordinary rise and spectacular fall of BlackBerry. Harper Collins Publishers.

Mudrack, P. E. (1989a). Defining group cohesiveness: A legacy of confusion? Small Group Research, 20(1), 37–49.

Mudrack, P. E. (1989b). Group cohesiveness and productivity: A closer look. Human Relations, 42(9), 771–785.

Muhlenhoff, J. (2016). Applying mixed methods in entrepreneurship to address the complex interplay of structure and agency in networks: A focus on the contribution of qualitative approaches. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 37–62). Springer Nature.

Mulunga, S. N., & Nazdanifarid, R. (2014). Review of social inclusion, social cohesion and social capital in modern organization. Global Journal of Management and Business Research, 14(3), 14–20.

Najmaei, A. (2016). Using mixed methods designs to capture the essence of complexity in the entrepreneurship research: An introductory essay and a research agenda. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 13–36). Springer Nature.

Namjoofard, N. (2014). An examination of factors of employee-centered corporate social responsibility and their relationship with the employee’s motivation toward generating innovation (Doctoral dissertation, Argosy University, Chicago).

Oketch, M. O. (2004). The corporate stake in social cohesion. Corporate Governance: THe International Journal of Business in Society, 4(3), 5–19.

Quince, T. (2001). Entrepreneurial collaboration: Terms of endearment or rules of engagement? University of Cambridge.

Rees, K., & Ebrahim, S. (2001). Promises and problems of systematic reviews. Heart Drug, 1(5), 247–248.

Reitz, J. G., & Banerjee, R. (2005). Racial inequality and social cohesion in Canada: Findings from the Ethnic Diversity Survey. In: Canadian Ethnic Studies Meeting.

Schlaile, M. P., & Ehrenberger, M. (2016). Complexity, cultural evolution, and the discovery and creation of (social) entrepreneurial opportunities: Exploring a memetic approach. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 63–92). Springer Nature.

Schultz, C., Mietzner, D., & Hartmann, F. (2016). Action research as a viable methodology in entrepreneurship research. In E. S. Berger & A. Kuckertz (Eds.), Complexity in entrepreneurship, innovation and technology research – Applications of emergent and neglected methods (pp. 267–286). Springer Nature.

Schiefer, D., & Van der Noll, J. (2017). The essentials of social cohesion: A literature review. Social Indicators Research, 132(2), 579–603.

Senge, P. M. (1990). The fifth discipline: The art and practice of the learning organization. Doubleday.

Sethi, R., Smith, D. C., & Park, C. W. (2001). Cross-functional product development teams, creativity, and the innovativeness of new consumer products. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(1), 73–85.

Smith, P., & Polanyi, M. (2008). Social norms, social behaviors and health: An empirical examination of a model of social capital. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 27(4), 456–463.

Stacey, R. D. (2011). Strategic management and organisational dynamics: The challenge of complexity (6th ed.). Harlow, Pearson.

Stevenson, H. H. & Jarillo, J. C. (2007). A paradigm of entrepreneurship: Entrepreneurial management. In: Entrepreneurship (pp. 155–170). Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg.

Stewart, A., Lee, F. K., & Konz, G. N. (2008). Artisans, athletes, entrepreneurs, and other skilled exemplars of the way. Journal of Management, Spirituality & Religion, 5(1), 29–55.

Sulistyo, H., & Ayuni, S. (2020). Competitive advantages of SMEs: The roles of innovation capability, entrepreneurial orientation, and social capital. Contaduría y Administración, 65(1), 1–18.

Vveinhardt, J., & Banikonyte, J. (2017). Managerial solutions that increase the effect of group synergy and reduce social loafing. Management of Organizations: Systematic Research, 78(1), 109–129.

Ward, L. F. (1918). Glimpses of the cosmos: A mental autobiography. New York, G.P. Putnam’s Sons.

Webster, J. & Watson, R. T. (2002). Analyzing the past to prepare for the future: Writing a literature review. MIS Quarterly, 26(2), xiii-xxiii.

Werth, M. (2002). The joy of life: The idyllic in French art, circa 1900. CA, University of California Press.

Wise, S. (2014). Can a team have too much cohesion? The dark side to network density. European Management Journal, 32(5), 703–711.

Witges, K. A., & Scanlan, J. M. (2015). Does synergy exist in nursing? A concept analysis. Nursing Forum, 50(3), 189–195.

Wong, L. (1992). The effects of cohesion on organizational performance: A test of two models (Doctoral dissertation, Texas Tech University).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Minhas, J., Sindakis, S. Implications of Social Cohesion in Entrepreneurial Collaboration: a Systematic Literature Review. J Knowl Econ 13, 2760–2791 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00810-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13132-021-00810-0