Abstract

Objectives

Cardiometabolic health during pregnancy has potential to influence long-term chronic disease risk for both mother and offspring. Mindfulness practices have been associated with improved cardiometabolic health in non-pregnant populations. The objective was to evaluate diverse studies that explored relationships between prenatal mindfulness and maternal cardiometabolic health.

Method

An integrative review was conducted in January 2023 across five databases to identify and evaluate studies of diverse methodologies and data types. Quantitative studies that examined mindfulness as an intervention or exposure variable during pregnancy and reported any of the following outcomes were considered: gestational weight gain (GWG), blood glucose, insulin resistance, gestational diabetes, inflammation, blood pressure, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Qualitative studies were included if they evaluated knowledge, attitudes, or practices of mindfulness in relation to the above-mentioned outcomes during pregnancy.

Results

Fifteen eligible studies were identified, and 4 received a “Good” quality rating (1/7 interventional, 1/5 observational, 2/2 qualitative). Qualitative studies revealed interest among pregnant women in mindfulness-based practices for managing GWG. Some beneficial effects of mindfulness interventions on maternal glucose tolerance and blood pressure were identified, but not for other cardiometabolic outcomes. Observational studies revealed null direct associations between maternal trait mindfulness and cardiometabolic parameters, but one study suggests potential for mindful eating to mitigate excess GWG and insulin resistance.

Conclusions

There currently exists limited quality evidence for mindfulness practices to support prenatal cardiometabolic health. Further rigorous studies are required to understand whether prenatal mindfulness-based interventions, either alone or in combination with other lifestyle modalities, can benefit cardiometabolic health.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

The Developmental Origins of Health and Disease paradigm explains how suboptimal conditions or exposures in utero affect fetal development through alterations in cells, tissues, and organs, thus contributing to long-term disease risk in the offspring (Barker et al., 2002; Gluckman et al., 2007). In this regard, maternal cardiometabolic health during pregnancy, which encompasses gestational weight gain (GWG), glycemic control (including gestational diabetes mellitus [GDM]), blood pressure, and inflammation, plays a critical role in influencing child health outcomes (Brand et al., 2021; Han et al., 2021; Montazeri et al., 2018; Oken et al., 2009), while also influencing risk of adverse perinatal outcomes and long-term chronic disease risk for the mother (Farrar et al., 2016; Liu et al., 2016). Therefore, achieving optimal cardiometabolic health during pregnancy is an important public health consideration as it has potential to influence individuals’ health trajectories across generations.

In developed societies such as the United States, approximately 60% of pregnant women gain weight in excess of recommendations (Carmichael et al., 1997; Webb, 2008), 3–7% of pregnancies are affected by GDM (Catalano et al., 2012), and up to 16% are affected by hypertensive disorders (Ford, 2022). Excess GWG and GDM are both associated with increased odds of cesarean delivery and large for gestational age newborns (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2018a; Rogozińska et al., 2019), and additionally, GDM is associated with a 70% odds of future development of type 2 diabetes for the mother (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2018a).

Even in the absence of excess GWG or overt GDM diagnosis, maternal insulin resistance and hyperglycemia (collectively referred to as “glycemic control” in this paper) exert effects along a continuum and are associated in a graded, dose-dependent manner with increased risk of adverse maternal and child outcomes, including increased risk for childhood obesity and maternal risk for developing type 2 diabetes (Coustan et al., 2010; Durnwald et al., 2011; HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, 2008, 2010a, 2010b; Vambergue et al., 2000; Walsh et al., 2011). Similarly, elevated blood pressure during pregnancy, even in the absence of preeclampsia, is associated with risk of preterm delivery and neonatal intensive care unit admission (Greenberg et al., 2021), and positively associated with offspring blood pressure (Jansen et al., 2019). Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy are also the leading cause of pregnancy-related mortality in the United States (Ford et al., 2022). Therefore, appropriate interventions and guidance on achieving a healthy cardiometabolic state during pregnancy (i.e., appropriate GWG, good glycemic control, blood pressure within normal ranges) are relevant for all pregnant women.

Existing interventions that aim to improve aspects of cardiometabolic health during pregnancy primarily focus on physical activity or dietary behaviors, but little attention is given to the role of psychological well-being in the pathophysiology of these conditions, or to the influence of poor psychological well-being on the very health behaviors that such intervention studies are attempting to alter (i.e., driving poor eating habits and sedentariness). Growing evidence supports that prenatal psychological well-being is associated with GWG, dysregulated glycemia, GDM, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (Caplan et al., 2021; Hartley et al., 2015; Horsch et al., 2016; Matthews et al., 2018; Shay et al., 2020). Observational studies have found that higher maternal distress (i.e., stress, depression, anxiety) may affect these markers of cardiometabolic health through direct pathways such as altered cortisol patterning (e.g., flattened cortisol decline and higher evening cortisol) (Gilles et al., 2018), lower insulin sensitivity index (Valsamakis et al., 2017), and reduced cardiac vagal control (i.e., lower high-frequency heart rate variability) (Rouleau et al., 2016), or through indirect pathways such as reduced dietary quality (Boutté et al., 2021; Lindsay et al., 2018) or physical activity levels (Sinclair et al., 2019).

Maternal stress and lifestyle factors may also interactively impact cardiometabolic health-related outcomes (Marques et al., 2015). For example, in a prospective longitudinal study, pregnant mothers’ higher negative emotions mitigated the beneficial effect of a Mediterranean diet on insulin resistance (Lindsay et al., 2020). In another prospective study, pre-existing anxiety disorders potentiated the effects of elevated maternal body mass index on development of hypertension during gestation (Winkel et al., 2015). Improving maternal psychological well-being holds potential to exert direct, beneficial effects on the underlying pathways involved in the pathophysiology of cardiometabolic outcomes in pregnancy. It also remains to be determined whether approaches to support maternal psychological well-being can indirectly promote improved cardiometabolic health by supporting engagement in and adherence to healthy lifestyle behaviors.

The prevalence of psychological distress (i.e., stress, depression, anxiety) during pregnancy has been reported to range from 5 to 20% in the US depending on the tools used for screening or diagnosis (Biaggi et al., 2016; Dunkel Schetter & Tanner, 2012). However, prior studies posit that even higher rates of low-grade chronic maternal distress may exist due to unique physiological, hormonal, socioeconomic, and interpersonal changes experienced during this time (Berthelot et al., 2020; Lin et al., 2020; Obrochta et al., 2020). Given the detrimental consequences of psychological distress on maternal outcomes, many studies have investigated the psychological impact of stress management interventions among pregnant women. Of these, mindfulness-based interventions have been frequently studied in recent years, as the benefits of mindfulness practice in non-pregnant populations have gained increasing attention. Mindfulness may be defined as the awareness that arises through paying attention, on purpose, in the present moment, non-judgmentally (Kabat-Zinn, 2003). Numerous reviews indicate that mindfulness-based interventions can reduce maternal perceived stress, depression, and anxiety during pregnancy (Dhillon et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2016; Lever Taylor et al., 2016; Lucena et al., 2020). Despite these favorable effects on psychological outcomes, there is a limited understanding of how mindfulness practice is associated with cardiometabolic outcomes during pregnancy. A number of systematic reviews of studies from non-pregnant populations indicate beneficial cardiometabolic effects of mindfulness-based interventions (Black & Slavich, 2016; Carriere et al., 2018; Dunn et al., 2018; Ni et al., 2021; Pascoe et al., 2017; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2020). However, there has been no published review to date assessing this evidence in the context of pregnancy.

A synthesis of current evidence from prenatal studies is required to understand whether and how these non-invasive, non-pharmacological approaches should be incorporated into future intervention studies with the goal of improving maternal health and pregnancy outcomes. We conducted a preliminary literature search that suggested a small number of diverse study types have been published on this topic in pregnancy cohorts (i.e., qualitative studies and quantitative studies with interventional and observational designs) although no pre-defined concept of gestational cardiometabolic health exists. Thus, a systematic review was deemed inadequate to comprehensively synthesize this literature given that it would require a narrow focus and would not accommodate heterogeneity in study designs and data types. Instead, an integrative review was considered the most appropriate approach as it serves to define concepts, review theories, synthesize evidence from diverse study methodologies, and analyze methodological issues to help guide future research (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005).

Therefore, this integrative review aimed to synthesize the existing evidence regarding the relationship between maternal mindfulness and cardiometabolic-related outcomes during pregnancy (i.e., GWG, GDM, glycemic control, insulin resistance, blood pressure, hypertensive disorders, inflammation). In addition to synthesizing quantitative data from existing observational and intervention studies, we also considered results from qualitative studies as these may be used to inform the design and implementation of future prenatal mindfulness interventions. This review also discussed ongoing research in this field and the limitations of existing work and suggested directions for future studies.

Method

Design

Given the infancy of the field of research on the physiological effects of mindfulness in pregnancy, an integrative literature review was selected as the review methodology as it facilitates a broad exploration of the topic across various study designs that incorporate diverse methodologies and generate various types of data (i.e., qualitative and quantitative), thereby including multiple perspectives. It also allows authors to define key concepts, analyze the existing evidence, and perform quality assessment of studies in the field, thus highlighting evidence gaps and needs for future studies to address. This approach differs from a scoping review which aims to identify the nature and extent of research evidence within a field when it is unclear what specific question should be addressed (Grant & Booth, 2009). Scoping reviews do not typically assess the quality of individual studies.

This integrative review was conducted following the guidelines of an established framework (Whittemore & Knafl, 2005) which includes the following five stages: (i) problem identification, (ii) literature search, (iii) data evaluation, (iv) data analysis, and (v) presentation of results and findings. After identifying the problem/research question, as outlined in the introduction section of this paper, key variables of interest were agreed upon to develop the search terms and define inclusion and exclusion criteria. An electronic search was conducted across several online databases to augment efficiency and to capture a broad scope of potentially relevant literature. The quality of each article selected for inclusion was systematically evaluated using validated quality assessment tools applicable to the individual study designs (see below under “Study Quality Assessment” for further details). Analysis was performed on included articles by abstracting and organizing data into pre-defined categories within tables for quantitative studies and by summarization of key themes identified from qualitative studies.

Study Eligibility

Randomized controlled trials, quasi-experimental studies, observational studies (prospective or cross-sectional), and qualitative studies were all deemed eligible for this review. Conference abstracts, clinical guidelines, study protocols, and review papers were excluded, as were articles not published in the English language. Intervention studies were considered for eligibility if the intervention was either primarily based on mindfulness or incorporated some elements of mindfulness practice during pregnancy. Observational studies had to include a validated measure of mindfulness captured during pregnancy as an exposure variable in the analysis, and qualitative studies had to explore attitudes or beliefs surrounding mindfulness practice among pregnant women to be considered eligible. Yoga intervention studies were not deemed eligible unless they specifically described mindfulness techniques (e.g., mindful breathing or meditation) as a component of their intervention. This approach ensured that Westernized yoga practices that solely utilize the physical aspects of yoga as a form of exercise were not included. Interventions that exclusively targeted health behavior changes (e.g., dietary changes, exercise) without any concomitant mindfulness component were also excluded, as were studies conducted in the preconception or postpartum periods.

The pre-defined outcomes of interest for this review spanned four domains of cardiometabolic health in pregnancy: (i) gestational weight gain (absolute gain across pregnancy or rate of weight gain per week), (ii) glycemic control (fasting or post-prandial glucose, HbA1c, fasting insulin or measures of insulin sensitivity/resistance, GDM diagnosis), (iii) blood pressure (systolic or diastolic measures, hypertension, preeclampsia), and (iv) inflammation (inflammatory cytokines, C-reactive protein). For quantitative studies, objective or self-reported measures of at least one of the above prenatal cardiometabolic factors had to be assessed as a primary or secondary outcome variable to be considered eligible. Qualitative studies that considered at least one of these factors in relation to mindfulness practice as part of an interview or focus group in pregnant populations were considered eligible. Articles were excluded if they only reported maternal psychological outcomes, or if they only reported neonatal/birth outcomes without including any prenatal maternal cardiometabolic indices.

Search Strategy and Study Selection

The published literature was searched using strategies created by consensus discussion between all authors and then final review by a librarian. These strategies were established using a combination of standardized terms and key words related to mindfulness, pregnancy, and cardiometabolic health (weight gain, glycemic control, blood pressure, inflammation); the complete search strategy is available as Supplementary Information. The following electronic databases were independently searched by one author (KLL) and a librarian in January 2023, without restriction by location or year: PubMed, CINAHL, Web of Science, Scopus, and PsycINFO. Articles returned within each database were independently screened by two authors (KLL, LEG) to identify those that potentially met eligibility criteria. Screening was initially conducted by title and abstract, and then by review of the full text of selected articles. The authors compared and discussed selected studies to resolve disagreements and reach consensus on the final article selection for in-depth review. Those selected were reviewed in their entirety by all authors and articles deemed not meeting inclusion criteria were discarded following reviewer consensus. Where required, corresponding authors of identified studies were contacted to obtain clarification on study methodology or results. The reference lists of selected studies and related review articles were also screened to identify further potential studies for inclusion.

Data Extraction

Data extracted from the final selected studies included the study design, study location, sample size, participant demographics, details of the intervention/control group or exposure for quantitative studies, details of interview questions or discussion points for qualitative studies, and study results as pertaining to our pre-defined primary and secondary outcomes. Extracted data were summarized in tables and cross-checked for accuracy among reviewers, and discrepancies resolved by discussion.

Study Quality Assessment

Appraisal of individual study quality was conducted independently by two authors (LEG, YG) using tailored tools according to study design. For quantitative studies, the quality assessment tools for controlled intervention studies and observational cohort/cross-sectional studies developed jointly by methodologists from the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) and Research Triangle Institute International were used (U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, 2013). For qualitative studies, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative checklist was used (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018). These tools were designed to assist reviewers in focusing on concepts that are key for critical appraisal of the internal validity of a study. Each tool includes items for evaluating potential flaws in study methods or implementation, and data analysis. Options of “yes,” “no,” or “cannot determine/not reported/not applicable” (or “Can’t Tell” on the CASP checklist) were selected in response to each item on each tool. For each item where “no” was selected, the potential risk of bias that could be introduced by that flaw in the study design or implementation was considered (this was true for both quantitative and qualitative studies). If the risk of bias was deemed to be high, the paper was deemed to have a critical flaw which resulted in an overall rating of poor quality. Outcomes of “cannot determine” and “not reported” for any item in the checklists for quantitative studies were also noted as representing potential flaws, but not necessarily critical flaws depending on the context in which they occurred and number of items in the checklist with such outcomes. Similarly, a rating of “Can’t Tell” for any item in the CASP checklist for qualitative studies was carefully considered a potential flaw in the research methodology and the impact that the uncertain information may have had on the study results was discussed among authors. A final rating of “good”, “fair,” or “poor” was assigned to each included study by each reviewing author, indicating either a low risk of bias, susceptible to some bias, or at high risk of bias, respectively. Individual appraisal results were discussed during face-to-face meetings such that the item ratings for each study were compared with rationale provided by each author. Where discrepancies arose, the rationale was deliberated among all authors using consensus decision-making to reach agreement on the final rating.

Data Synthesis

Key features and primary results of included studies were organized into tables. A narrative synthesis of findings structured around geographical location, study design and primary research question, data collection methods and/or intervention, and results of the outcome measures pertaining to cardiometabolic health was provided.

Results

Study Selection

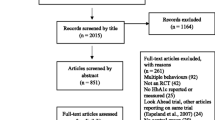

An overview of the published article search and selection process is described in Fig. 1. The original search returned a total of 224 articles across all databases. This was reduced to 120 unique articles after removal of duplicates. Screening by title and abstract identified 44 potentially relevant articles with 90% agreement between authors. After full text screening of these articles and further discussion regarding potential eligibility, 31 were excluded by consensus: 3 study protocols, 7 review papers, 9 original research articles that did not incorporate a mindfulness exposure, 11 original research articles that did not report relevant maternal physiological outcomes, and 1 editorial comment. Literature cited in other review papers were screened for potential eligibility, but this did not identify any additional articles not already returned in our database search. One article returned by the database search was carefully considered for eligibility as the methodology only briefly mentioned mindfulness as a component of the behavioral intervention without further detail of the extent or content of the mindfulness practices employed (Opie et al., 2016). Contact with the corresponding author of that article confirmed that one-to-one counseling with study participants broadly incorporated mindful eating approaches, albeit in a non-standardized manner. The authors of this paper deemed that article to be relevant for inclusion based on the communication received. Review of reference lists identified one further article that was potentially eligible for inclusion (Redman et al., 2017); contact with the corresponding author of that paper confirmed that mindfulness techniques were systematically integrated into the diet and lifestyle intervention, and hence, the article was included. This brought the total number of included articles to 14; 12 quantitative studies, comprising of 7 interventions (Bublitz et al., 2023; Crovetto et al., 2021; Epel et al., 2019; Muthukrishnan et al., 2016; Opie et al., 2016; Redman et al., 2017; Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014) and 5 observational studies (Braeken et al., 2017; Headen et al., 2019; Lindsay et al., 2021; Matthews et al., 2018; Mennitto et al., 2021), as well as 2 qualitative studies (Green et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2014).

Study Quality Assessment

Detailed results of our quality assessment for each included study are presented in Supplementary Information Table S1. Among the intervention studies, only one was deemed to be of “Good” quality (Crovetto et al., 2021), and four were rated as “Fair” quality (Bublitz et al., 2023; Epel et al., 2019; Opie et al., 2016; Redman et al., 2017) and two of “Poor” quality (Muthukrishnan et al., 2016; Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014). The primary flaws identified that reduced study quality among the studies rated as “Fair” were failure to conduct a true intention-to-treat analysis (e.g., failure to account for missing outcome data) (Vorland et al., 2021; White et al., 2012), inadequate reporting of how missing data were handled, and baseline differences between intervention and control groups. Among the observational studies, only one was deemed to be of “Good” quality (Headen et al., 2019), two of “Fair” quality (Braeken et al., 2017; Lindsay et al., 2021), and two of “Poor” quality (Matthews et al., 2018; Mennitto et al., 2021). Various flaws were identified among the observational studies with a “Fair” and “Poor” quality designation, including risk of bias in the cohort selected for analysis or in outcome measures, and inadequate inclusion of potential confounding factors. Each of the two qualitative studies received a rating of “Good” quality.

Description of Included Studies

The characteristics of included quantitative studies are described in Supplementary Information Table S2.

Intervention Studies

Two of the intervention studies had a quasi-experimental design, such that data for the control groups were obtained from a convenience sample of pregnant patients through electronic medical records (Opie et al., 2016) or the control arm comprised either those who refused participation in the intervention arm due to schedule conflicts (Epel et al., 2019). Five of the intervention studies were randomized controlled trials. Among these, two involved three study arms such that two alternative intervention groups were compared to one another as well as a control group, which reflected treatment as usual (Crovetto et al., 2021; Redman et al., 2017). Three studies targeted high-risk pregnancies including those with a history of hypertensive disorder, risk factors for small for gestational age birth, or with a diagnosis of GDM (Bublitz et al., 2023; Crovetto et al., 2021; Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014).

Four of the intervention studies delivered an intervention component that was centered around standardized or adapted versions of existing mindfulness programs, such as Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) (Crovetto et al., 2021). One study delivered a non-standardized intervention that combined mindful eating didactic sessions with yoga practice (Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014). The other two intervention studies were centered around diet and lifestyle behavior change to support pregnancies with overweight and/or obesity and incorporated some mindful eating or mindful stress reduction guidance as minor components of the interventions (Opie et al., 2016; Redman et al., 2017). For the cardiometabolic outcome measures, one study focused solely on GWG (Altazan et al., 2019), a second study only focused on glycemic control (Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014), and two studies only focused on blood pressure–related outcomes (Bublitz et al., 2023; Muthukrishnan et al., 2016). The other three studies reported some combination of two of these outcome domains, but none reported on all three. Each of these cardiometabolic outcome measures was either objectively measured by the research team or abstracted from the medical record (e.g., diagnosis of GDM or preeclampsia). No study reported on inflammatory outcome measures.

Observational Studies

The included observational studies employed a mixture of study designs, including prospective cohort (Braeken et al., 2017; Lindsay et al., 2021), cross-sectional (Matthews et al., 2018; Mennitto et al., 2021), and a retrospective observational study (Headen et al., 2019) that conducted secondary data analysis from one of the intervention studies included in this review (Epel et al., 2019). None of the observational studies involved pregnancies with underlying medical complications. Four studies evaluated trait mindfulness of pregnant mothers using standardized, validated constructs (Braeken et al., 2017), and the final study evaluated how neighborhood typology of pregnant women moderated the effectiveness of a structured mindfulness intervention on measured health outcomes (Headen et al., 2019). Three studies reported objectively measured cardiometabolic outcomes (Braeken et al., 2017; Headen et al., 2019; Lindsay et al., 2021) while two relied on maternal self-reported outcomes (Matthews et al., 2018; Mennitto et al., 2021). Matthews et al. (2018) evaluated the relationship between trait mindfulness and self-reported GWG by trimester but did not specify in the methodology if those in second or third trimesters were asked to recall GWG in their earlier trimesters, or if they only reported total GWG up until the time of completing the survey.

Qualitative Studies

Of the two qualitative studies included in this review, one conducted focus groups with 59 low-income pregnant women with overweight or obesity to gain their perspectives on the relationship between stress, eating behavior, and weight gain in pregnancy and their interest in engaging in a prenatal mindfulness-based intervention to help support diet and achieve a healthy GWG (Thomas et al., 2014). The authors of that study subsequently published the paper describing the results of the Mindful Moms Training intervention, which is also included in this review (Epel et al., 2019). The second qualitative study conducted interviews with 13 healthy pregnant women who had recently completed participation in a 12-week prenatal yoga intervention (Green et al., 2021). That study sought to gain insight to mothers’ experiences of the yoga intervention and their perceived barriers and facilitators to engaging in prenatal yoga for the prevention of excess GWG. Interview questions included an exploration of mothers’ perceptions of mindfulness and how it relates to GWG. The parent intervention study from which this qualitative study was derived was not identified in the published literature at the time of conducting this review.

Synthesis of Study Results

Table 1 summarizes the key results related to cardiometabolic outcomes for the included quantitative studies.

Intervention Studies

Of three studies reporting effects on GWG, only Redman et al. (2017) found a significantly lower proportion of excess GWG in both intervention arms versus control in their randomized controlled trial. However, the two quasi-experimental studies did not identify any significant benefit of the intervention, although Epel et al. (2019) reported a significantly higher proportion of GWG that fell below the recommended level according to BMI category compared to the control. Of note, the other quasi-experimental study was missing more than 50% of the GWG data for their control group (Opie et al., 2016).

For glycemic outcomes, no interventional effects were noted for GDM incidence, but there was benefit regarding maternal glucose concentrations. Specifically, GDM rates were not impacted by the MBSR intervention compared to control in the study by Crovetto et al. (2021), nor by the behavioral intervention incorporating a modest amount of mindful eating coaching in the quasi-experimental study by Opie et al. (2016), after adjusting for covariates. However, both Epel et al. (2019) and Youngwanichsetha et al. (2014) reported lower glucose values on glucose tolerance tests among their mindfulness intervention groups compared to control. Youngwanichsetha et al. (2014) additionally found modestly lower fasting glucose values in the intervention group versus control.

Results for mindfulness intervention effects on blood pressure were mixed across three studies, with two studies indicating some benefit, whereas one study showed no effect of intervention. Bublitz et al. (2023) reported significantly lower systolic and diastolic values (at rest) in the intervention group compared to control. While Muthukrishnan et al. (2016) reported no difference between groups in resting blood pressure values, they did demonstrate an improved blood pressure response to physical and psychological stress tests (i.e., a smaller increase in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure) compared to control. Crovetto et al. (2021) reported no effects of the mindfulness intervention on blood pressure, as well as no effects on rates of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension, compared to control.

Observational Studies

Two observational studies examined associations between self-reported mindfulness traits and GWG and reported some evidence that greater trait mindfulness associated with lower GWG across pregnancy. While Lindsay et al. (2021) reported no association between the total mindful eating score and rate of GWG per week in pregnant women with obesity, there was a relationship when examining subdomains of mindfulness. Specifically, there was a significant relationship with the distracted eating subscale from the mindful eating questionnaire, such that greater mindful eating practice in this domain associated with a lower rate of GWG. Matthews et al. (2018) reported that higher trait mindfulness scores were negatively associated with maternal self-reported GWG in the first trimester only. However, we note that the GWG data collection methods were incompletely described in that paper, which challenged interpretation of the results. In a secondary analysis, Headen et al. (2019) reported no moderating effect of participants’ neighborhood typology on the effect of a prenatal mindfulness intervention on rate of excess GWG.

Regarding glycemic-related outcomes, Lindsay et al. (2021) reported that higher mindful eating scores were significantly associated with lower insulin resistance in the third trimester of pregnancy, measured by the homeostasis model assessment of insulin resistance. Headen et al. (2019) identified a significant moderating effect of neighborhood typology on the effects of the Mindful Moms Training intervention on glucose tolerance in pregnancy, such that only those in the best-resourced and least-resourced neighborhoods were observed to have better glucose control following the intervention. Mennitto et al. (2021) reported incidence of GDM as the only glycemic-related outcome but found no association between trait mindfulness and its occurrence.

Only one observational study reported systolic and diastolic blood measurement outcomes but found no association between maternal trait mindfulness and either measure (Braeken et al., 2017). Similarly, trait mindfulness was not associated with incidence of gestational hypertension in the study by Mennitto et al. (2021).

Qualitative Studies

Themes identified by the focus groups conducted by Thomas et al. included “relationship between stress and eating” and “motivations for a stress reduction intervention during pregnancy” (Thomas et al., 2014). Most participants acknowledged a complex relationship between stress, emotions, and eating in their lives, recognizing tendencies for mindless eating under stress, and consequences for excess GWG. The participants also expressed enthusiasm about a mindfulness-based stress management intervention tailored to pregnancy that could help support healthy eating behaviors and healthy GWG. In particular, they were interested in a group intervention with other pregnant women that went beyond traditional dietary counseling by incorporating mindfulness and were optimistic that this type of intervention could help them cope with stress and address their concerns about GWG.

Green et al. (2021) identified 12 themes from their interviews with pregnant women who participated in a prenatal yoga intervention to help manage GWG. One of these themes, “prenatal yoga and weight,” was particularly related to mindfulness as participants reported that engaging in the yoga practice increased their sense of self-awareness and mindfulness in their daily lives, with beneficial effects on eating habits. For example, participants expressed that they became more mindful of what food they were putting into their body and how their dietary choices could affect the health of their baby and weight gain. Some also expressed that increasing levels of mindfulness helped them become aware of how much weight they were gaining and whether it was too much or too little.

Discussion

This integrative review presents a detailed synthesis of currently available evidence linking mindfulness practice in pregnancy to cardiometabolic-related outcomes in the mother. With the increasing popularity of studies that involve mindfulness interventions in pregnancy (Lucena et al., 2020), it is important to understand if potential benefits may extend beyond psychological aspects of maternal health and support cardiometabolic health outcomes, especially given rising rates of maternal obesity, GDM, and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. Growing evidence supports beneficial effects of mindfulness on weight management, glycemic, and blood pressure outcomes in non-pregnant populations (Black & Slavich, 2016; Carriere et al., 2018; Dunn et al., 2018; Ni et al., 2021; Pascoe et al., 2017; Scott-Sheldon et al., 2020). Although this integrative review found limited and mostly low-grade quantitative evidence to support benefits of mindfulness on cardiometabolic outcomes during pregnancy, the inclusion of high-quality qualitative evidence highlights promising attitudes among participants of mindfulness interventions and strengthens the premise to advance more rigorous research on this topic in prenatal populations. This review also highlights several methodological inadequacies across included studies, as well as heterogeneity among intervention studies regarding the type, intensity, and delivery of mindfulness-based approaches, which limits our ability to draw firm conclusions regarding the status of the evidence in this field. Notably, no study was identified that reported outcomes related to inflammatory markers during pregnancy, representing a missed opportunity to understand the underlying biological pathways that could link mindfulness practice to improvements in pregnancy outcomes.

Prenatal Mindfulness and GWG

Among intervention studies that delivered some type of formal mindfulness training, only Epel et al. (2019) reported GWG as an outcome but found no benefits for reduced rate of excess GWG compared to control. However, their finding that a higher proportion of women in the intervention group had GWG below the recommended range for their BMI category (overweight and obese groups) deserves further attention. This may not necessarily represent an adverse outcome given that the National Academy of Medicine guidelines for GWG (Rasmussen & Yaktine, 2009) have been criticized for being too generous and that those with pre-pregnancy obesity may benefit from less GWG to offset the adverse effects that higher adiposity may exert on pregnancy and infant outcomes (Barbour, 2012; Robillard, 2023).

While Redman et al. (2017) reported a significantly lower rate of excess GWG among pregnant women with obesity in both healthy lifestyle intervention groups (in-person and remotely delivered) compared to control, we note that mindfulness techniques represented a minor component of those interventions compared to other lifestyle practices (i.e., nutrition counseling, exercise). Although we are unable to decipher which component of that broader lifestyle intervention may have exerted the observed effects, it is plausible that incorporating mindfulness approaches could enhance the effects of lifestyle behavior change counseling on maternal GWG. For example, in a weight loss randomized controlled trial in non-pregnant adults, a diet and exercise intervention combined with mindfulness training was found to significantly reduce reward-driven eating behavior compared to diet and exercise intervention alone, and the reduction in reward-based eating mediated the effect of the combined intervention arm on weight loss at the 12-month follow-up time point (Mason et al., 2016). Thus, further research is required to elucidate whether mindfulness strategies that support maternal psychological well-being in pregnancy can augment the effectiveness of traditional behavioral lifestyle interventions with respect to important cardiometabolic health outcomes.

Observational studies included in this review identified modest associations between maternal mindful eating behavior (Lindsay et al., 2021) or trait mindfulness (Matthews et al., 2018) and GWG, albeit the quality of this evidence was fair to poor. However, the two qualitative studies indicate that pregnant women are both interested in and perceived benefit from engaging in mindfulness practices to support healthy GWG (Green et al., 2021; Thomas et al., 2014). Importantly, Thomas et al. (2014) conducted their focus groups among a population of low-income, predominantly Hispanic pregnant women, who typically experience higher rates of excess GWG compared to non-Hispanic White women and therefore have potential to exert greater benefits from such interventions. Although Green et al. (2021) evaluated participant feedback on a prenatal yoga intervention rather than formal mindfulness training, participants of that study reported how the yoga practice increased their awareness of health practices and weight management during pregnancy and specifically identified a sense of greater mindfulness from which they perceived benefit. These qualitative studies, which both received a “Good” quality rating, can help inform future prenatal mindfulness interventions with respect to approaches used to elicit motivation and engagement among target participants.

Mindfulness and Glycemic Control

Only one intervention study (Crovetto et al., 2021) and one observational study (Mennitto et al., 2021) included in this review reported the incidence of GDM in relation to either formal mindfulness training or measured trait mindfulness, respectively, and neither found any evidence for beneficial effects of mindfulness in this regard. We note that the study by Crovetto et al. was the only intervention study included in this review that received a “Good” quality rating, thus increasing credibility of the results reported. However, that study was not powered to assess the impact of mindfulness practice on the incidence of GDM, and therefore, we cannot conclude with certainty that there was a null effect. The quasi-experimental lifestyle intervention by Opie et al. (2016) reported a notably lower rate of GDM in the intervention group versus control, but this was only statistically significant before adjusting for confounding factors. However, it is not possible to attribute the observed differences in GDM rate between groups to increased maternal mindfulness given that the intervention group only received mindful eating advice in a non-systematic manner during nutrition consultations, rather than undergoing any type of formal mindfulness training or counseling on mindful eating. Furthermore, the study by Opie et al. (2016) received a “Fair” quality rating and the reliability of the results reported should be carefully considered.

Despite this lack of evidence with respect to GDM as a diagnostic outcome, our review did identify several studies that implicate potential beneficial relationships between increased maternal mindfulness and glycemia during pregnancy as measured on a continuous spectrum. Lower glucose concentrations in the intervention groups versus control following glucose tolerance tests in two of the intervention studies may indicate a role for formal mindfulness practices to help improve glucose-insulin homeostasis (Epel et al., 2019; Youngwanichsetha et al., 2014). However, we also must interpret these results with caution given that those studies received a “Fair” and “Poor” quality rating, respectively. Data from one observational study also implicates higher maternal mindful eating behavior to be associated with lower levels of insulin resistance in the third trimester (Lindsay et al., 2021), although that study also received a “Fair” quality rating and was not powered to detect the observed associations. Collectively, these findings hold clinical relevance given that moderately elevated maternal glucose concentrations, even in the absence of GDM, have been found to be positively associated with neonatal and child adiposity (HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group, 2009; Kaul et al., 2022). Also, higher levels of gestational insulin resistance, even among those receiving treatment for GDM, have been associated with greater risk for adverse pregnancy outcomes (Benhalima et al., 2019; Cosson et al., 2022).

Future well-designed and higher quality prenatal mindfulness intervention studies are clearly needed to see if these findings with respect to maternal glycemia can be replicated. However, it is recommended that such studies also consider the underlying influence of maternal demographic factors on the efficacy of such interventions, and how the interventions can be appropriately tailored to meet the needs of underserved populations. For example, Headen et al. (2019) demonstrated that neighborhood typology (classified according to wealth and resource access) moderated the effects of the Mindful Moms intervention on glycemic control following a glucose challenge test. Structural and social determinants of health are likely responsible for these disparate effects (American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 2018b) as exposure to poverty and having low access to resources, such as healthy food and healthcare, may adversely affect glycemia to the extent that a mindfulness intervention is unable to counteract. Furthermore, individuals living in poverty and with low resource access are more likely to experience heightened psychological stress and various competing demands for time (Bermúdez-Millán et al., 2011; Vaughan et al., 2023), which may challenge their ability to attend and sufficiently engage in supportive health services such as those offered by the Mindful Moms intervention. Interestingly, Headen et al. (2019) found that those from poor neighborhoods with moderate resource access experienced improved glucose tolerance following the intervention compared to the control arm, which may indicate that better neighborhood access to resources supports one’s ability to benefit from a prenatal mindfulness practice despite having a low-income level.

Mindfulness and Blood Pressure

The limited available evidence to date describing relationships between prenatal mindfulness and maternal blood pressure shows mixed results. The largest intervention study included in our review, which also received the highest quality rating compared to other intervention studies, reported null effects of a MBSR program on rates of preeclampsia or gestational hypertension (Crovetto et al., 2021). However, we note that these represented secondary outcome measures in that study and that the primary outcome, rate of small for gestational age at birth, was significantly lower in the mindfulness intervention group compared to control. The apparent success of the intervention on reducing small for gestational age may have been achieved through biological mechanisms related to psychological stress reduction rather than any notable change in maternal blood pressure. Meanwhile, a pilot study of remotely delivered mindfulness training among a small sample of pregnant women with a history of hypertensive disorders reported benefits for reduction of systolic and diastolic blood pressure (Bublitz et al., 2023). However, a risk of bias in the results of that study was noted due to failure to statistically compare key characteristics between intervention and control groups at baseline which could indicate unmeasured confounding in the analysis. Similarly, the apparent positive results on post-stressor blood pressure values reported by Muthukrishnan et al. (2016) following their 5-week mindful meditation program should be interpreted with caution given the high risk of bias in that study due to failure to report various methodological procedures as well as participant retention and adherence rates. Only two observational studies were identified that reported on blood pressure as an outcome variable but neither found any significant association with maternal trait mindfulness (Braeken et al., 2017; Mennitto et al., 2021), although the credibility of one of these studies is questionable due to major flaws and a high risk of bias (Mennitto et al., 2021).

Comparison with Existing Studies from Pregnant and Non-pregnant Populations

Evidence from a growing body of intervention trials in non-pregnant adults demonstrates that increasing psychological well-being has the capacity to causally improve metabolic health outcomes. The most commonly used psychological well-being interventions have involved mindfulness and yoga practice and provide evidence for changes across multiple indicators of metabolic health. Specifically, several systematic reviews have concluded that psychological well-being interventions, primarily yoga based, can improve measures of glycemic control, including fasting and post-prandial glucose, HbA1c, and measures of adiposity and obesity risk (Chew et al., 2017; Jayawardena et al., 2018; Pascoe et al., 2017; Ramamoorthi et al., 2019; Thind et al., 2017). A further two systematic reviews report beneficial effects of mindfulness-based interventions on weight loss and obesity-related eating behaviors (Carriere et al., 2018; Dunn et al., 2018). In addition, four systematic reviews have interrogated the effects of mindfulness meditation or yoga practice on changes to the immune system, and all concluded there were reductions in proinflammatory processes, with evidence for cell-mediated immunity (Black & Slavich, 2016; Djalilova et al., 2019; Falkenberg et al., 2018; Moraes et al., 2018) and dose–response improvements (Black & Slavich, 2016; Djalilova et al., 2019).

These studies provide biological plausibility and support the translation of mindfulness-based interventions for the improvement of maternal cardiometabolic health in pregnancy. This is a growing field and, thus far in the context of pregnancy, systematic reviews have focused on the effects of yoga and mindfulness interventions upon broad categories of maternal psychological health, including quality of life, self-efficacy, perceived stress, anxiety, and depression scores. Of the five systematic reviews that investigated the effects of yoga (Curtis et al., 2012; Kawanishi et al., 2015; Kwon et al., 2020; Mooventhan, 2019; Sheffield & Woods-Giscombe, 2016) and the three that investigated mindfulness interventions (Dhillon et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2016; Lever Taylor et al., 2016), all argue in favor of positive intervention effectiveness for psychological health outcomes. However, there are broad concerns regarding the limited number of RCTs, particularly with active controls, inconsistency across the types of intervention practices used, and a lack of understanding regarding which components of the intervention are necessary to drive the perceived improvements in psychological health, all of which are shared concerns with the studies included in this integrative review.

Limitations and Future Research

This integrative review is the first to synthesize the literature on mindfulness during pregnancy in relation to cardiometabolic health outcomes, thereby expanding our current knowledge of potential benefits of mindfulness beyond the psychological realm alone. By including diverse study designs in our review, we have captured broad perspectives about the potential relevancy of considering maternal trait mindfulness in relation to cardiometabolic health in pregnancy, as well as the acceptability and efficacy of prenatal mindfulness interventions for supporting maternal cardiometabolic health. Our rigorous literature search was conducted in partnership with a research librarian to ensure accuracy, and incorporated search terms that spanned four domains of cardiometabolic health (weight gain, glycemic control, blood pressure, inflammation) to facilitate broad capture of studies that addressed physiological health measures with established links to maternal and offspring cardiometabolic health during pregnancy and beyond. Furthermore, we conducted an extensive quality assessment of included studies to help guide the interpretation and reliability of results reported.

We note two limitations of this review. Firstly, although our search was not restricted by country or year of publication, we did limit the search to articles published in the English language which could have resulted in exclusion of other potentially relevant studies. Secondly, we restricted our eligibility to studies that reported maternal cardiometabolic health outcomes during pregnancy, which may have missed studies that demonstrate postpartum maternal or offspring cardiometabolic health benefits associated with mindfulness traits assessed, or interventions delivered, during the prenatal period.

Given the high rates of maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide (Centers for Disease Control & Prevention, 2020, 2021; Kotit & Yacoub, 2021), which are often related to poor cardiometabolic health in the pre- and perinatal periods (Marschner et al., 2022), there is a critical need to consider all avenues for prevention and reduction of adverse pregnancy-related outcomes through safe, accessible, and patient-centered adjunctive approaches to traditional medical management. The evidence presented in this integrative review highlights prenatal mindfulness as a potentially relevant target for further research in this regard. However, the literature published on this topic to date is heterogeneous with respect to study design, interventions, and outcome measures and the majority of identified studies suffer from moderate to high risk of bias. Thus, the largely null results reported in this review should not discourage researchers from conducting further studies of mindfulness and cardiometabolic health in pregnant populations as there is a need for more rigorous data to determine the potential pathways of associations and efficacy of interventions for improving maternal physiological health outcomes. Moreover, since the emotional and mental well-being benefits of mindfulness practice during pregnancy have been repeatedly shown in prior studies (Dhillon et al., 2017; Hall et al., 2016; Lever Taylor et al., 2016; Lucena et al., 2020), pregnant participants of future research trials that aim to examine the impact on gestational cardiometabolic health outcomes can, at the very least, expect to find mental health benefits from establishing a regular mindfulness practice.

Future prenatal mindfulness intervention trials should aim for randomized designs that are adequately powered to test the impact on pre-defined cardiometabolic health outcome(s). They should consider an active control group, such as group classes on general pregnancy well-being, rather than standard prenatal care, which may provide a more rigorous comparison against the effects of mindfulness-based interventions. Participant retention, handling and reporting of missing data, and conducting intention-to-treat analyses that appropriately account for missing data are currently major weaknesses that must be addressed to elevate the quality of evidence in this field. More complex study designs may also be required to tease apart the effects of mindfulness intervention components from more traditional behavior change approaches that target maternal cardiometabolic health (e.g., nutrition counseling, exercise), and determine whether cardiometabolic health benefits in pregnancy can be augmented when these intervention components are administered in combination. A significant knowledge gap remains with respect to the effects of prenatal mindfulness-based interventions on maternal markers of inflammation, as no studies reporting on inflammatory markers, even as secondary outcome measures, were identified by this review. Yet, immune/inflammatory-related pathways represent a plausible mechanism by which mindfulness interventions may exert beneficial effects on weight gain, glycemic control, and blood pressure, as well as numerous other potential adverse pregnancy outcomes. There may also be other physiological markers of interest, such as maternal resting heart rate, that could benefit from prenatal mindfulness interventions and represent markers of downstream maternal and offspring cardiometabolic health outcomes. For example, low maternal heart rate has been associated with lower birthweight babies (Odendaal et al., 2019), while high resting heart rate has been linked to elevated risk of GDM (Qiu et al., 2022).

Observational studies have potential to generate important data to inform the need for and direction of intervention trials. Yet, we identified less observational compared to intervention studies in this review and two of the included observational studies were deemed to have critical flaws that limit the interpretability and reliability of the data reported. Moreover, none of the observational studies examined inflammatory markers as outcome measures, representing a missed opportunity to capture data that could inform the underlying mechanisms by which mindfulness practice may exert positive cardiometabolic effects. We recommend that future observational studies assess maternal trait mindfulness and mindful eating behavior in pregnancy and examine their associations with objectively measured markers of cardiometabolic health that span the domains of weight gain, glycemic control, blood pressure, and inflammation. Consistency in measures used to assess mindfulness, as well as in gestational timing of assessments, will assist with replication across studies.

Qualitative studies also provide valuable insight to participants’ attitudes toward and experiences of mindfulness as a tool to support their physiological health, in addition to the established psychological health benefits. The only qualitative studies that met eligibility criteria for this review focused on mindfulness in relation to GWG. Given the known associations between psychological stress and cardiometabolic risk factors including poor glycemic control, elevated blood pressure, and inflammation, and the potential for mindfulness practice to improve resiliency and psychological well-being, there is a need to explore whether pregnant individuals might also be receptive to mindfulness interventions with the goal of improving a broader spectrum of physiological health markers beyond GWG alone. Further, given that most studies of mindfulness interventions conducted in Western countries to date primarily target non-Hispanic White and highly educated populations (Cramer et al., 2016; Khoury et al., 2015), more qualitative data are required to elucidate how future interventions in this field can be more inclusive of and appropriately tailored toward diverse racial and ethnic groups and those from lower socioeconomic status backgrounds. This is especially important given that individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups are more likely to be affected by poor cardiometabolic health outside of and during pregnancy compared to non-Hispanic White individuals (Akam et al., 2022; Bentley-Lewis et al., 2014; Hedderson et al., 2010; Ross et al., 2020). Indeed, the included qualitative study by Thomas et al. (2014) found that low-income, predominantly Hispanic pregnant women were interested in a pregnancy-tailored mindfulness intervention, but it remains to be determined if other minority groups in the US, or low-income people from different geographical locations, also share these beliefs.

This integrative review identified mixed evidence, primarily of fair-to-poor quality, for potential benefits of mindfulness practices to support cardiometabolic health in pregnancy. More rigorous evidence exists from non-pregnancy studies regarding beneficial effects of mindfulness-based or yoga interventions on inflammatory processes, glycemic control, and adiposity. Thus, further rigorous studies are required to understand whether mindfulness is an efficacious approach, either alone or in combination with other lifestyle modalities, to improve gestational cardiometabolic health outcomes, as well as potential downstream physiologic health benefits for the offspring and for the mothers postpartum.

Data Availability

No original data were generated in this research. All data are presented in the paper and Supplementary Material.

References

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. (2018a). ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 190: Gestational diabetes mellitus. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 131(2), e49–e64. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002501

American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology. (2018b). ACOG Committee Opinion No. 729: Importance of social determinants of health and cultural awareness in the delivery of reproductive health care. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 131(1), e43–e48. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000002459

Akam, E. Y., Nuako, A. A., Daniel, A. K., & Stanford, F. C. (2022). Racial disparities and cardiometabolic risk: New horizons of intervention and prevention. Current Diabetes Reports, 22(3), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11892-022-01451-6

Altazan, A. D., Redman, L. M., Burton, J. H., Beyl, R. A., Cain, L. E., Sutton, E. F., & Martin, C. K. (2019). Mood and quality of life changes in pregnancy and postpartum and the effect of a behavioral intervention targeting excess gestational weight gain in women with overweight and obesity: A parallel-arm randomized controlled pilot trial. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 19(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-019-2196-8

Barbour, L. A. (2012). Weight gain in pregnancy: Is less truly more for mother and infant? Obstetric Medicine, 5(2), 58–64. https://doi.org/10.1258/om.2012.120004

Barker, D. J., Eriksson, J. G., Forsén, T., & Osmond, C. (2002). Fetal origins of adult disease: Strength of effects and biological basis. International Journal of Epidemiology, 31(6), 1235–1239. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/31.6.1235

Benhalima, K., Van Crombrugge, P., Moyson, C., Verhaeghe, J., Vandeginste, S., Verlaenen, H., Vercammen, C., Maes, T., Dufraimont, E., De Block, C., Jacquemyn, Y., Mekahli, F., De Clippel, K., Van Den Bruel, A., Loccufier, A., Laenen, A., Minschart, C., Devlieger, R., & Mathieu, C. (2019). Characteristics and pregnancy outcomes across gestational diabetes mellitus subtypes based on insulin resistance. Diabetologia, 62(11), 2118–2128. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00125-019-4961-7

Bentley-Lewis, R., Powe, C., Ankers, E., Wenger, J., Ecker, J., & Thadhani, R. (2014). Effect of race/ethnicity on hypertension risk subsequent to gestational diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Cardiology, 113(8), 1364–1370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2014.01.411

Bermúdez-Millán, A., Damio, G., Cruz, J., D’Angelo, K., Segura-Pérez, S., Hromi-Fiedler, A., & Pérez-Escamilla, R. (2011). Stress and the social determinants of maternal health among Puerto Rican women: A CBPR approach. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 22(4), 1315–1330. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2011.0108

Berthelot, N., Lemieux, R., Garon-Bissonnette, J., Drouin-Maziade, C., Martel, E., & Maziade, M. (2020). Uptrend in distress and psychiatric symptomatology in pregnant women during the Coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Acta Obstetricia Et Gynecologia Scandinavica, 99(7), 848–855. https://doi.org/10.1111/aogs.13925

Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S., & Pariante, C. M. (2016). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014

Black, D. S., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Science, 1373(1), 13–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/nyas.12998

Boutté, A. K., Turner-McGrievy, G. M., Wilcox, S., Liu, J., Eberth, J. M., & Kaczynski, A. T. (2021). Associations of maternal stress and/or depressive symptoms with diet quality during pregnancy: A narrative review. Nutrition Reviews, 79(5) 495–517. https://doi.org/10.1093/nutrit/nuaa019

Braeken, M. A., Jones, A., Otte, R. A., Nyklíček, I., & Van den Bergh, B. R. (2017). Potential benefits of mindfulness during pregnancy on maternal autonomic nervous system function and infant development. Psychophysiology, 54(2), 279–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.12782

Brand, J. S., Lawlor, D. A., Larsson, H., & Montgomery, S. (2021). Association between hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and neurodevelopmental outcomes among offspring. JAMA Pediatrics, 175(6), 577–585. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.6856

Bublitz, M. H., Salmoirago-Blotcher, E., Sanapo, L., Ayala, N., Mehta, N., & Bourjeily, G. (2023). Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary effects of mindfulness training on antenatal blood pressure. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 165, 111146. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2023.111146

Caplan, M., Keenan-Devlin, L. S., Freedman, A., Grobman, W., Wadhwa, P. D., Buss, C., Miller, G. E., & Borders, A. E. B. (2021). Lifetime psychosocial stress exposure associated with hypertensive disorders of pregnancy. American Journal of Perinatology, 38(13), 1412–1419. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0040-1713368

Carmichael, S., Abrams, B., & Selvin, S. (1997). The pattern of maternal weight gain in women with good pregnancy outcomes. American Journal of Public Health, 87(12), 1984–1988. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.87.12.1984

Carriere, K., Khoury, B., Gunak, M. M., & Knauper, B. (2018). Mindfulness-based interventions for weight loss: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Obesity Reviews, 19(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12623

Catalano, P. M., McIntyre, H. D., Cruickshank, J. K., McCance, D. R., Dyer, A. R., Metzger, B. E., Lowe, L. P., Trimble, E. R., Coustan, D. R., Hadden, D. R., Persson, B., Hod, M., Oats, J. J., Group, H. S. C. R. (2012). The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome study: Associations of GDM and obesity with pregnancy outcomes. Diabetes Care, 35(4), 780–786. https://doi.org/10.2337/dc11-1790

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). Pregnancy mortality surveillance system. Retrieved August 14, 2022 from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). Severe maternal morbidity in the United States. Retrieved September 6, 2023 from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternalinfanthealth/severematernalmorbidity.html

Chew, B. H., Vos, R. C., Metzendorf, M. I., Scholten, R. J., & Rutten, G. E. (2017). Psychological interventions for diabetes-related distress in adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 9, CD011469. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD011469.pub2

Cosson, E., Nachtergaele, C., Vicaut, E., Tatulashvili, S., Sal, M., Berkane, N., Pinto, S., Fabre, E., Benbara, A., Fermaut, M., Sutton, A., Valensi, P., Carbillon, L., & Bihan, H. (2022). Metabolic characteristics and adverse pregnancy outcomes for women with hyperglycaemia in pregnancy as a function of insulin resistance. Diabetes and Metabolism, 48(3), 101330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabet.2022.101330

Coustan, D. R., Lowe, L. P., Metzger, B. E., & Dyer, A. R. (2010). The Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Paving the way for new diagnostic criteria for gestational diabetes mellitus. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(6), 654.e651-654.e656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.04.006

Cramer, H., Hall, H., Leach, M., Frawley, J., Zhang, Y., Leung, B., Adams, J., & Lauche, R. (2016). Prevalence, patterns, and predictors of meditation use among US adults: A nationally representative survey. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 36760. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep36760

Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. Retrieved February 2, 2023 from https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/

Crovetto, F., Crispi, F., Casas, R., Martín-Asuero, A., Borràs, R., Vieta, E., Estruch, R., & Gratacós, E. (2021). Effects of Mediterranean diet or mindfulness-based stress reduction on prevention of small-for-gestational age birth weights in newborns born to at-risk pregnant individuals: The IMPACT BCN randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 326(21), 2150–2160. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2021.20178

Curtis, K., Weinrib, A., & Katz, J. (2012). Systematic review of yoga for pregnant women: Current status and future directions. Evidence Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, 715942. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/715942

Dhillon, A., Sparkes, E., & Duarte, R. V. (2017). Mindfulness-based interventions during pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Mindfulness, 8(6), 1421–1437. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0726-x

Djalilova, D. M., Schulz, P. S., Berger, A. M., Case, A. J., Kupzyk, K. A., & Ross, A. C. (2019). Impact of yoga on inflammatory biomarkers: A systematic review. Biological Research for Nursing, 21(2), 198–209. https://doi.org/10.1177/1099800418820162

Dunkel Schetter, C., & Tanner, L. (2012). Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Current Opinions in Psychiatry, 25(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1097/YCO.0b013e3283503680

Dunn, C., Haubenreiser, M., Johnson, M., Nordby, K., Aggarwal, S., Myer, S., & Thomas, C. (2018). Mindfulness approaches and weight loss, weight maintenance, and weight regain. Current Obesity Reports, 7(1), 37–49. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13679-018-0299-6

Durnwald, C. P., Mele, L., Spong, C. Y., Ramin, S. M., Varner, M. W., Rouse, D. J., Sciscione, A., Catalano, P., Saade, G., Sorokin, Y., Tolosa, J. E., Casey, B., & Anderson, G. D. (2011). Glycemic characteristics and neonatal outcomes of women treated for mild gestational diabetes. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 117(4), 819–827. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0b013e31820fc6cf

Epel, E., Laraia, B., Coleman-Phox, K., Leung, C., Vieten, C., Mellin, L., Kristeller, J. L., Thomas, M., Stotland, N., Bush, N., Lustig, R. H., Dallman, M., Hecht, F. M., & Adler, N. (2019). Effects of a mindfulness-based intervention on distress, weight gain, and glucose control for pregnant low-income women: A quasi-experimental trial using the orbit model. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 26(5), 461–473. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-019-09779-2

Falkenberg, R. I., Eising, C., & Peters, M. L. (2018). Yoga and immune system functioning: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 41(4), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-018-9914-y

Farrar, D., Simmonds, M., Bryant, M., Sheldon, T. A., Tuffnell, D., Golder, S., Dunne, F., & Lawlor, D. A. (2016). Hyperglycaemia and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: Systematic review and meta-analysis. British Medical Journal, 354, i4694. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i4694

Ford, N. D., Cox, S., Ko, J. Y., Ouyang, L., Romero, L., Colarusso, T., Ferre, C. D., Kroelinger, C. D., Hayes, D. K., & Barfield, W. D. (2022). Hypertensive disorders in pregnancy and mortality at delivery hospitalization — United States, 2017–2019. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 71, 585–591. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7117a1external

Gilles, M., Otto, H., Wolf, I. A. C., Scharnholz, B., Peus, V., Schredl, M., Sutterlin, M. W., Witt, S. H., Rietschel, M., Laucht, M., & Deuschle, M. (2018). Maternal hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) system activity and stress during pregnancy: Effects on gestational age and infant’s anthropometric measures at birth. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 94, 152–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2018.04.022

Gluckman, P. D., Hanson, M. A., & Beedle, A. S. (2007). Early life events and their consequences for later disease: A life history and evolutionary perspective. American Journal of Human Biology, 19(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.20590

Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

Green, J., James, D., Larkey, L., Leiferman, J., Buman, M., Oh, C., & Huberty, J. (2021). A qualitative investigation of a prenatal yoga intervention to prevent excessive gestational weight gain: A thematic analysis of interviews. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 44, 101414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101414

Greenberg, V. R., Silasi, M., Lundsberg, L. S., Culhane, J. F., Reddy, U. M., Partridge, C., & Lipkind, H. S. (2021). Perinatal outcomes in women with elevated blood pressure and stage 1 hypertension. American Journal of Obstetetrics and Gynecology, 224(5), 521.E1–521.E11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.10.049

Hall, H. G., Beattie, J., Lau, R., East, C., & Anne Biro, M. (2016). Mindfulness and perinatal mental health: A systematic review. Women and Birth, 29(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.08.006

Han, V. X., Patel, S., Jones, H. F., Nielsen, T. C., Mohammad, S. S., Hofer, M. J., Gold, W., Brilot, F., Lain, S. J., Nassar, N., & Dale, R. C. (2021). Maternal acute and chronic inflammation in pregnancy is associated with common neurodevelopmental disorders: A systematic review. Translational Psychiatry, 11(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41398-021-01198-w

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. (2008). Hyperglycemia and adverse pregnancy outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine, 358(19), 1991–2002. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa0707943

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. (2009). Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Associations with neonatal anthropometrics. Diabetes, 58(2), 453–459. https://doi.org/10.2337/db08-1112

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. (2010a). Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Associations with maternal body mass index. British Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 117(5), 575–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2009.02486.x

HAPO Study Cooperative Research Group. (2010b). Hyperglycemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcome (HAPO) study: Preeclampsia. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 202(3), 255.E1–255.E7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2010.01.024

Hartley, E., McPhie, S., Skouteris, H., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., & Hill, B. (2015). Psychosocial risk factors for excessive gestational weight gain: A systematic review. Women and Birth, 28(4), e99–e109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2015.04.004

Headen, I., Laraia, B., Coleman-Phox, K., Vieten, C., Adler, N., & Epel, E. (2019). Neighborhood typology and cardiometabolic pregnancy outcomes in the maternal adiposity metabolism and stress study. Obesity, 27(1), 166–173. https://doi.org/10.1002/oby.22356

Hedderson, M. M., Darbinian, J. A., & Ferrara, A. (2010). Disparities in the risk of gestational diabetes by race-ethnicity and country of birth. Paediatric and Perinatal Epidemiology, 24(5), 441–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-3016.2010.01140.x

Horsch, A., Kang, J. S., Vial, Y., Ehlert, U., Borghini, A., Marques-Vidal, P., Jacobs, I., & Puder, J. J. (2016). Stress exposure and psychological stress responses are related to glucose concentrations during pregnancy. British Journal of Health Psychology, 21(3), 712–729. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjhp.12197

Jansen, M. A., Pluymen, L. P., Dalmeijer, G. W., Groenhof, T. K. J., Uiterwaal, C. S., Smit, H. A., & van Rossem, L. (2019). Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy and cardiometabolic outcomes in childhood: A systematic review. European Journal of Preventive Cardiology, 26(16), 1718–1747. https://doi.org/10.1177/2047487319852716

Jayawardena, R., Ranasinghe, P., Chathuranga, T., Atapattu, P. M., & Misra, A. (2018). The benefits of yoga practice compared to physical exercise in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes and Metabolic Syndrome, 12(5), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dsx.2018.04.008

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2003). Mindfulness-based interventions in context: Past, present, and future. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 10, 144–156. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.bpg016

Kaul, P., Savu, A., Yeung, R. O., & Ryan, E. A. (2022). Association between maternal glucose and large for gestational outcomes: Real-world evidence to support Hyperglycaemia and Adverse Pregnancy Outcomes (HAPO) study findings. Diabetes Medicine, 39(6), e14786. https://doi.org/10.1111/dme.14786

Kawanishi, Y., Hanley, S. J., Tabata, K., Nakagi, Y., Ito, T., Yoshioka, E., Yoshida, T., & Saijo, Y. (2015). Effects of prenatal yoga: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Nihon Koshu Eisei Zasshi, 62(5), 221–231. https://doi.org/10.11236/jph.62.5_221

Khoury, B., Sharma, M., Rush, S. E., & Fournier, C. (2015). Mindfulness-based stress reduction for healthy individuals: A meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 78(6), 519–528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2015.03.009

Kotit, S., & Yacoub, M. (2021). Cardiovascular adverse events in pregnancy: A global perspective. Global Cardiology Science and Practice, 2021(1), e202105. https://doi.org/10.21542/gcsp.2021.5

Kwon, R., Kasper, K., London, S., & Haas, D. M. (2020). A systematic review: The effects of yoga on pregnancy. European Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology and Reproductive Biology, 250, 171–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejogrb.2020.03.044

Lever Taylor, B., Cavanagh, K., & Strauss, C. (2016). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions in the perinatal period: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 11(5), e0155720. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0155720

Lin, S. C., Tyus, N., Maloney, M., Ohri, B., & Sripipatana, A. (2020). Mental health status among women of reproductive age from underserved communities in the United States and the associations between depression and physical health. A Cross-Sectional Study. PLoS ONE, 15(4), e0231243. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231243

Lindsay, K. L., Buss, C., Wadhwa, P. D., & Entringer, S. (2018). Maternal stress potentiates the effect of an inflammatory diet in pregnancy on maternal concentrations of tumor necrosis factor alpha. Nutrients, 10(9), 1252. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10091252

Lindsay, K. L., Buss, C., Wadhwa, P. D., & Entringer, S. (2020). The effect of a maternal Mediterranean diet in pregnancy on insulin resistance is moderated by maternal negative affect. Nutrients, 12(2), 420. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12020420

Lindsay, K. L., Most, J., Buehler, K., Kebbe, M., Altazan, A. D., & Redman, L. M. (2021). Maternal mindful eating as a target for improving metabolic outcomes in pregnant women with obesity. Frontiers in Bioscience, 26(12), 1548–1558. https://doi.org/10.52586/5048

Liu, P., Xu, L., Wang, Y., Zhang, Y., Du, Y., Sun, Y., & Wang, Z. (2016). Association between perinatal outcomes and maternal pre-pregnancy body mass index. Obesity Reviews, 17(11), 1091–1102. https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12455

Lucena, L., Frange, C., Pinto, A. C. A., Andersen, M. L., Tufik, S., & Hachul, H. (2020). Mindfulness interventions during pregnancy: A narrative review. Journal of Integrative Medicine, 18(6), 470–477. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joim.2020.07.007

Marques, A. H., Bjorke-Monsen, A. L., Teixeira, A. L., & Silverman, M. N. (2015). Maternal stress, nutrition and physical activity: Impact on immune function, CNS development and psychopathology. Brain Research, 1617, 28–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brainres.2014.10.051