Abstract

Objectives

While stressors of military deployment are known to have profound effects on health, less is known about effective methods for promoting health. A few studies have examined the effectiveness of mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs) in this context; however, fewer have used an active control group and objective health indicators. Therefore, this study examined the effects of an MBI in comparison to a similarly structured traditional stress management intervention (progressive muscle relaxation, PMR) on health indicators among military personnel.

Method

Using a 2 (pre vs. post) × 3 (group: MBI, PMR vs. inactive control group, ICG) experimental mixed design, participants (MBI, n = 118; PMR, n = 55; ICG, n = 156) answered baseline and post-intervention self-reported measures. Physiological parameters were assessed before and after each session.

Results

Results showed that MBI is superior to PMR and ICG, leading to higher increases in mindfulness, positive affect, and self-care, and greater decreases in physical complaints. This is also confirmed by objective data. Participants in the MBI demonstrated improved heart rate variability and reduced heart rate, while no change was evident for PMR and ICG. However, both MBI and PMR were equally effective in reducing strain.

Conclusions

This study provides further evidence for the effectiveness of MBIs in this specific professional group based on rigorous methodology (comparing to a competing intervention, self-reported and objective measures). MBI is even more effective than PMR as a traditional health intervention in terms of promoting mindfulness, positive affect, and health behavior, as well as reducing complaints.

Preregistration

This study is not preregistered.

Similar content being viewed by others

The ability to respond appropriately to and recover from stressful situations is fundamental to long-term psychological functioning and mental health. This applies in particular to high-risk occupations where intense work stress is an unavoidable part of the job. For example, military personnel are at increased risk of cognitive, emotional, and physiological impairments and mental health problems when exposed to a stressful environment for an extensive time (Haase et al., 2016; Stanley et al., 2011). Serving in the military can involve stressful situations for the individual in basic operations as well as during deployment (Abendroth, 2021). Studies have shown that military personnel are vulnerable to a wide range of mental health issues, including anxiety, depression, PTSD, and substance use disorders: Between 20 and 25% of all soldiers with and without deployment suffered from a mental illness in a period of 12 months (Ursano et al., 2014; Zimmermann et al., 2015), while in the civilian population, the annual prevalence for mental illnesses is 10.8% (Meyer et al., 2021). Even for those who have not seen combat, military service can be a stressful experience (Clark, 2018). A recent study showed that 35% of a total of 1142 military personnel and 46% of 469 leaders rate their work stress level as “high” or “very high” (Krick et al., 2020). To counter this, workplace health promotion programs (WHPPs) are also implemented in the military context. A WHPP is a systematic strategy to improve employees’ health-related knowledge, attitude, skills, and behaviors. In general, these programs include interventions addressing physical activity, stress prevention, healthy nutrition, addiction prevention, and job design (European Network for Workplace Health Promotion, 2018). As Krick et al. (2020) showed, 71% of military personnel reported a high need for workplace health promotion offers. Especially in such high-risk work contexts, effective health promotion measures are needed to promote resources and thus maintain and improve occupational health.

Mindfulness is such a resource — characterized by “paying attention in a particular way, on purpose, in the present moment, and non-judgmentally” (Kabat-Zinn, 1994, p. 4). According to Baer et al. (2006), mindfulness encompasses a set of abilities, including (1) describing present thoughts, sensations, and emotions (Describe); (2) perceiving moment-to-moment inner and external experiences (Observe); (3) without judging and evaluating these present experiences (Non-judge); (4) without automatically reacting to them (Non-react); and (5) being aware of present actions (Act with Awareness). These different mindfulness skills can be developed and promoted by mindfulness-based interventions (MBIs). MBIs have been increasingly developed for WHPPs (Hülsheger et al., 2015) and are mostly based on the Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction program (MBSR; Kabat-Zinn, 2013). Previous reviews and meta-analyses have shown the effectiveness of MBIs in the workplace in terms of a decrease in psychological distress, burnout, and anxiety and an increase in mindfulness and well-being (Bartlett et al., 2019; Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020).

While specific occupational contexts such as the healthcare and education sectors are highly represented in mindfulness research, there is a distinct paucity of research regarding other job contexts (Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020). Several authors highlighted the importance of investigating the impact of MBIs across other occupational contexts, especially those who have a high need and where high work stress is an unavoidable part of the job, such as the military context. The extent to which this specific professional group benefits is worth exploring (Bartlett et al., 2019; Lomas et al., 2019). It is conceivable that MBIs may be also effective in military personnel (Clark, 2018). However, the military can be characterized as a specific, “male-oriented” job context with a particular culture. The military culture is characterized by an emphasis on “toughness,” self-confidence, and other traditional male gender norms such as the suppression of the outward expression of emotions (Jakupcak et al., 2014; Thompson & Pleck, 1986), which may theoretically conflict with the attitudes and norms commonly adopted in MBI (e.g., acceptance, self-disclosure, vulnerability, non-striving; Kabat-Zinn, 2013). The term “male-oriented” does not necessarily depend on gender but more reflects an occupational role understanding and work culture of “toughness,” self-confidence, and strength which could be a result of military training and socialization processes (Krick & Felfe, 2020).

As highlighted by Hepner et al. (2022), research on mindfulness programs in real-world military settings is scant. Several adaptations of the traditional MBSR have been developed particularly for the military context, e.g., mindfulness-based mind fitness training (MMFT; Stanley et al., 2011) and mindfulness-based attention training (MBAT; Jha et al., 2020). Intervention studies in the military context (especially those examining MMFT and MBAT) have mainly focused on MBIs as a means of cognitive remediation and examined effects on working memory and attention (Jha et al., 2020; Stanley & Jha, 2009; Zanesco et al., 2019). Furthermore, previous studies in the military context have mainly focused on deployed personnel (Jha et al., 2010, 2020; Zanesco et al., 2019) or veterans (Goldberg et al., 2020; Marchand et al., 2021). Most of these studies predominantly focused on “deficit-based” mental health outcomes, i.e., specific mental disorders such as PTSD, depression, or anxiety (Goldberg et al., 2020; Marchand et al., 2021), representing only one part of the broader understanding of health and well-being. Less is known for personnel who are actively on duty but not necessarily deployed abroad. Especially, knowledge about the effects on nonclinical deficit-based health criteria such as strain and physical health complaints and “asset-based” health criteria such as positive affect, resources (i.e., mindfulness), or health-relevant behavior (i.e., self-care) is scarce. Effects on strain, mindfulness, and affect have already been examined in the education and healthcare sector, but are rarely considered in the military context, and evidence is mixed: Previous studies showed either no (for positive affect and perceived stress; Haase et al., 2016; Jha et al., 2020) or mixed results (for negative affect and mindfulness, e.g., Haase et al., 2016; Jha et al., 2010, 2020). Physical health, positive affect, or health-relevant behavior are called “asset-based” health indicators and are also relevant for health and well-being (Lomas et al., 2019). However, they have received little attention (Krick & Felfe, 2020), but may be also relevant to the military context, and thus require closer consideration. Increasingly, researchers emphasize that the effectiveness of MBIs should also be evaluated using objective physiological data to cross-validate findings on self-reported health indicators (Brown et al., 2021; Morton et al., 2020; Virgili, 2015). However, previous evidence still seems mixed (Backlund, 2022). In particular, there are hardly any studies using objective physiological health indicators such as heart rate variability (HRV) or heart rate (HR) in the military context (Chen et al., 2022; Hepner et al., 2022).

Most studies have not used an active control group (Bartlett et al., 2019; Goldberg et al., 2020) which makes it difficult to identify the extent to which the positive effects are a result of mindfulness per se (Jamieson & Tuckey, 2017; Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020). Previous studies using active control groups examined different interventions such as leadership courses, information on workplace stress, dog therapies, communication training, diary and sleep monitoring, or lifestyle intervention (Bartlett et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020). There are only a few studies that compare MBIs with traditional stress management interventions (e.g., yoga or progressive muscle relaxation; Vonderlin et al., 2020). Several researchers highlighted the need for more research using established workplace health promotion interventions such as yoga or progressive muscle relaxation (PMR) as active controls to assess the comparative benefits of MBIs and identify potential unique effects compared to other effective workplace health promotion interventions (Bartlett et al., 2019; Krick & Felfe, 2020; Vonderlin et al., 2020).

Aims, Hypotheses, and Contribution

Taken together these research limitations, the present study aims to examine the effectiveness of an MBI on self-reported “asset-based” (positive: resources [i.e., mindfulness], health-relevant behavior [i.e., self-care], and affect [i.e., positive affect]) and “deficit-based” (negative: strain and psychosomatic health complaints) health criteria among active-duty military personnel comparing pre- and post measures between an intervention group (MBI) and an active (PMR) and an inactive control group. As a comparative intervention in the active control group, we chose PMR (Jacobsen, 1929) because it is a widely used, validated, standardized, and well-established intervention aiming at the reduction of stress and improvement of relaxation and overall well-being (Payne, 2000; Wittchen & Hoyer, 2011). The effectiveness of PMR has been widely shown in a variety of research settings, both clinical and work contexts (e.g., Silveira et al., 2020; Sundram et al., 2016). Therefore, it serves as a rigorous benchmark for evaluating MBIs. We additionally include objective physiological indicators (i.e., HRV and HR) to cross-validate our findings. We regard mindfulness, strain, health complaints, positive affect, HRV, and HR as primary outcomes, as these characterize crucial indicators of effectiveness in MBI studies. We view self-care as a secondary outcome, as it has received less attention in previous research. Yet, it remains a compelling aspect to explore within the context of MBIs, as self-care generally is a relevant resource for psychological functioning and workplace health (Franke et al., 2014; Krick et al., 2019).

Effectiveness on Self-reported Asset-Based (Positive) Health Indicators

Mindfulness

Not surprisingly, MBIs should lead to more self-reported mindfulness. Examining effects on mindfulness can be viewed as a manipulation control and is particularly important for intervention studies in which the content and processes of established mindfulness interventions have been modified (Jamieson & Tuckey, 2017). It is conceivable that MBIs may differentially affect certain aspects of mindfulness more than others (Lomas et al., 2019). Since the mindfulness exercises in the MBI in this study particularly address the four sub-facets Act with Awareness, Observe, Non-react, and Non-judge, we expect a positive effect on these four facets in the intervention group. As mindfulness is not a key ingredient of PMR, there should be no or lower effects on mindfulness. Nevertheless, PMR may also promote “Observing” and “Acting with Awareness” to some extent when attention is focused on muscle tension and relaxation. We expect the following:

-

H1a: Mindfulness (and its facets: Act with Awareness, Non-react, Non-judge, Observe) will increase more in the intervention group than for those in the active and inactive control group.

Positive Affect

Positive affect is one aspect of pleasurable and positive experiences and describes the extent to which an individual subjectively experiences positive moods such as joy, interest, and enthusiasm (Miller, 2011). As mindfulness plays an important role in self- and emotion regulatory processes and influences mood (Brown & Ryan, 2003), positive affect should be positively influenced by MBIs. The exercises in the MBI address dealing with difficult feelings and help participants to accept difficult feelings rather than avoiding or suppressing them and show how to be more aware of positive experiences. Via its influence on attention and awareness (Teper et al., 2013), mindfulness should promote effective executive control and thus enhance the capacity for effective regulation of emotions. It can be assumed that the MBI increases participants’ emotion regulation and thus promotes positive affect. There is considerable evidence that MBIs have beneficial effects on affective experiences (e.g., Anderson et al., 2007; Carmody & Baer, 2008). However, studies in the military context did not find effects on positive affect which may be due to their specific focus on attention regulation. Regarding PMR, there are no theoretical reasons for the effects of PMR on positive affect. Based on these assumptions, we aim to provide more evidence for the effects of MBIs on positive affect in the military context and expect the following:

-

H1b: Positive affect will increase more in the intervention group than for those in the active and inactive control group.

Health-Relevant Behavior

Self-care describes how employees take care of their own health at work (Franke et al., 2014). Employees high in self-care prioritize their own health, are aware of health-related warning signals, and actively promote their health at work (e.g., taking breaks, healthy sitting, and time management, improving work environment and work organization; Krick et al., 2022; Pischel et al., 2023). Many studies have shown the positive effects of self-care on employee health (Franke et al., 2014; Klug et al., 2019, 2022). Self-care is an important resource for employee health that deserves more attention in the study of MBI effectiveness in the workplace (Krick & Felfe, 2020). Krick and Felfe (2020) have already shown a positive effect of an MBI on self-care among police officers. They argued that mindfulness might help to improve awareness of bodily symptoms and overload at work at an early stage to allow taking counter actions (e.g., recovery, self-management, demanding and accepting support). Mindfulness exercises and discussions on strategies to be more mindful should enable participants to take care of themselves and foster self-care. Mindfulness and self-leadership are theoretically connected, as they both are based on self-regulation processes (Brown & Ryan, 2003). There are no studies regarding effects of PMR on self-care. Tensing and relaxing muscle groups (PMR) may to some extent improve self-care by strengthening awareness of body sensations. Based on the given reasoning, we expect that the MBI should unfold higher effects on self-care in comparison to PMR. Based on these assumptions, we aim to replicate the findings of Krick and Felfe (2020) and hypothesize the following:

-

H1c: Self-care will increase more in the intervention group than for those in the active and inactive control group.

Effectiveness on Self-reported Deficit-Based (Negative) Health Indicators

Psychological Strain

Psychological strain or irritation can be seen “as a state of mental impairment resulting from a perceived goal discrepancy” (Mohr et al., 2006, p. 198). Psychological strain is characterized by not being able to detach from work (cognitive irritation) and emotionally irritable reactions (emotional irritation; Mohr et al., 2005). In contrast to mental disorders, psychological strain is more general in its definition and measurement, involving psychophysical and behavioral symptoms not specific to a given disorder. Strain can be seen as an indicator of distress. Previous meta-analyses and studies already found that MBIs are beneficial in reducing distress in the workplace (e.g., Janssen et al., 2018; Virgili, 2015), even for other occupations with a specific work culture such as the police (Krick & Felfe, 2020). However, there were no active control groups.

Psychosomatic Health Complaints

In addition to mental irritability, psychosomatic health complaints are also considered common symptoms of a stress reaction and include more physical, but also psychosomatic symptoms such as headaches, back pain, or gastrointestinal complaints. Clark (2018) called for future research on the effectiveness of MBI on physical health in the military context. This is also underlined by Goldberg et al. (2020) who stated that the benefits of MBIs beyond other health interventions on physical health are less clear. We assume that an MBI has beneficial effects on health complaints for several reasons: First, mindfulness exercises (e.g., body scan) help to notice symptoms and painful body sensations at an early stage so that appropriate action can be taken (rest, change of posture, etc.). Second, systematic mindful body movements help to prevent and reduce physical tensions (by mobilization, activation, and relaxation). Third, participants are encouraged to actively take care of their health. Krick and Felfe (2020) have already shown the beneficial effects of an MBI on health complaints for police officers. Based on previous findings and the given reasoning, we expect to replicate the effect of MBI on psychological strain and health complaints in the military context and to provide more evidence for the effectiveness on more nonclinical negative health indicators in this high-risk context.

As an individual’s body responds to stress with muscle tension leading to pain or discomfort, and tense muscles are a signal of the body indicating stress, PMR teaches how to relax muscles through a two-step process: by (a) systematically tensing particular muscle groups in your body and (b) releasing the tension and noticing how muscles feel when they are relaxed. PMR thus will lead to lower overall tension and therefore might help to reduce psychological strain and psychosomatic health problems such as stomachache and headache. Studies in the clinical context have already shown the effectiveness of PMR on distress (Jaya & Thakur, 2020; Sundram et al., 2016) and based on our reasoning regarding PMR, tensing and relaxing muscles should also affect strain and health complaints. We therefore expect the following:

-

H2: Psychological strain (a) and health complaints (b) will decrease more in the intervention group and the active control group than in the inactive control group.

Effectiveness on Objective Health Indicators

Heart Rate Variability

HRV is a commonly used objective physiological marker of stress, cardiovascular and mental health, and autonomic functioning (Christodoulou et al., 2020; Kim et al., 2018). It describes the variation in the time intervals of successive heartbeats (which is influenced by autonomic regulation) and reflects the activity of the parasympathetic nervous system and the cardiac vagal tone (Brown et al., 2021; Christodoulou et al., 2020). A higher HRV physiologically indicates lower stress, higher psychological flexibility, effective self-regulation, higher emotion regulation, and a reduced risk of mental illnesses (e.g., Brown et al., 2021; Christodoulou et al., 2020). There are several systematic reviews and meta-analyses on the effects of MBIs on HRV (Brown et al., 2021; Rådmark et al., 2019; Tung & Hsieh, 2019). Some evidence showed that MBIs increase HRV (Christodoulou et al., 2020; Krick & Felfe, 2020; Tung & Hsieh, 2019); however, most of the recent meta-analyses showed mixed and inconclusive results (Backlund, 2022; Brown et al., 2021; Rådmark et al., 2019). For example, Tung and Hsieh (2019) showed mixed results with some studies showing an increase in the widely used indicator rmssd (root-mean-square of successive R-R-interval differences), while some studies showed no effects on rmssd. Christodoulou et al. (2020) showed similar results. Rådmark et al. (2019) found a very small, but also non-significant effect of MBI on rmssd. In line with this finding, Brown et al. (2021) found that MBIs are not effective in increasing HRV relative to control conditions. Regarding less-rigorous analysis of pre-post change in the intervention groups alone, there was a significant small-medium increase in HRV from pre- to post-MBI intervention. Overall, these meta-analyses only include a few studies with healthy populations (e.g., 1 of 10, Rådmark et al., 2019; 6 of 10, Backlund, 2022; 2 of 18, Tung & Hsieh, 2019), and only two studies were conducted with military samples (i.e., combat veterans; Brown et al., 2021; Wahbeh et al., 2016). Although studies with active military samples are rare, a study by Krick and Felfe examined police officers and showed an increase in HRV in the intervention group, while the inactive control group showed no changes (Krick & Felfe, 2020). Regarding control groups, only a few studies used active control groups (e.g., 4 of 19 studies, Brown et al., 2021; 5 of 10, Backlund, 2022; 3 of 10, Rådmark et al., 2019). Only one study used a traditional stress management intervention.

These findings show uncertainties on how MBIs affect HRV and highlight the importance of larger, more rigorously conducted studies on physiological outcomes with MBIs being compared to active controls. We therefore aim to replicate the findings of Krick and Felfe (2020), provide more evidence for the effects of MBIs on HRV for the military context, and strengthen the previous evidence base on HRV by using both active and inactive control groups.

As MBIs appear to improve self-regulation, emotion regulation, and cognitive control, these benefits should also be reflected physiologically in higher HRV (Christodoulou et al., 2020). Since PMR teaches individuals to reduce their muscle tone and muscles are part of the sympathetic nervous system, PMR is also assumed to decrease the level of sympathetic arousal (thus might indirectly increase the parasympathetic activity; Groß & Kohlmann, 2021).

-

H3a: HRV will increase more in the intervention group than for those in the active and inactive control group.

Heart Rate

HR is used as a cardiovascular marker and reflects the activity of the sympathetic nervous system. An increased HR is linked to cognitive and physiological arousal and mental effort (Critchley et al., 2013). Previous studies have shown effects of meditation practices on HR (Ditto et al., 2006; Ospina et al., 2008; Pascoe et al., 2017; Rubia, 2009), in terms of a decrease. Several studies in the clinical context also show a decrease in HR after MBIs (Carlson et al., 2007; Joo et al., 2010; Zeidan et al., 2010); however, there is less evidence for the work context. Amutio et al. (2015) showed a significant decrease in HR levels after MBSR in a self-selected group of physicians, while another study with teachers found no effect (Roeser et al., 2013). Johnson et al. (2014) examined the effects of the MMFT on HR in a convenience sample of two Marine infantry battalions and showed a sharper reduction in heart rate in the MMFT group than in the control group.

HR should decrease after the MBI because mindfulness exercises improve self-regulation, lead to relaxation, and thus are likely to lower HR as a sign of reduced sympathetic arousal. Regarding PMR, the change from muscle contraction to a relaxed state should affect the autonomic nervous system, which decreases the activity of the sympathetic nervous system and increases the parasympathetic nervous system, creating relaxed conditions. PMR relaxation techniques stimulate autonomic nerves, which act as regulators in the vascular system to lower peripheral resistance and increase blood vessel elasticity. The relaxed state should be reflected in a lower HR (Lehrer et al., 2007).

In comparison to PMR, mindfulness and MBIs address a wider range of inner regulation processes (i.e., awareness of cognitions, emotions, actions, and body sensations); therefore, effects on HRV and HR should be higher for the MBI group than for PMR. Based on these considerations and previous findings, we expect the following:

-

H3b: HR will decrease more in the intervention group than for those in the active and inactive control group.

This study provides important theoretical and practical contributions. By examining the effectiveness of an MBI in a military sample, this study helps to fill the evidence gap related to the effectiveness of MBIs in the military. Our findings provide more clarification regarding the effects on positive health outcomes, e.g., health-related behavior, and positive affect, that are relevant health indicators for resilience of military personnel. Furthermore, the use of objective physiological health indicators will complement findings from self-reported measures. By examining both an inactive and active control group, this study provides stronger evidence of the intervention effectiveness of MBIs and increases the internal validity of these studies as demanded by Jamieson and Tuckey (2017). By using two control groups, we are able to control for extraneous variables that consistently influence results across interventions, e.g., expectancy effects, and provide insight into the benefits and intervention effectiveness of a particular intervention program compared to a competing intervention and no intervention. Generally, studies examining specific high-risk occupations provide additional evidence on whether MBIs are effective at all in high-risk contexts with specific demands.

Regarding the practical contribution, our findings have important implications for workplace health promotion. Knowledge of the positive impact of workplace interventions on reducing stress-related mental health problems and physical health complaints and promoting resources for adaptive functioning helps organizations and practitioners select effective workplace health interventions. This study helps to clarify whether MBIs are effective workplace health interventions, not only in contexts where mindfulness is established and more common, but also in specific high-risk work contexts with a unique culture and set of experiences, challenges, and attitudes. Other interventions may be just as effective in producing desired benefits. Examining the effects of MBIs compared to other workplace health interventions can confirm the specific value of MBIs if this intervention is found to be superior to other interventions designed to achieve similar benefits. This knowledge would provide support for organizational investment choices.

Method

Participants

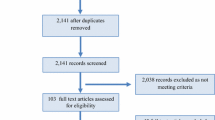

As shown by the participant flowchart (Fig. 1), n = 417 members of the German Armed Forces registered in our study. Due to several reasons (e.g., participation in less than four sessions of the MBI, failing to fill out post questionnaire due to illness, job transfer, or other reasons), the dropout rate was 21%. The final sample consisted of n = 329 participants. Within the overall sample, the mean age of participants was 29.99 years (SD = 10.84, range 19–61), 50.3% were male, 22% were leaders, and 28.6% had prior combat exposure. Participants served in different areas (Army 50%, Air Force and Navy each 9%, Central Medical Service 8%, Joint Support and Enabling Service 5%, and Cyber and Information Domain Service 5%). Overall, 74% were active-duty soldiers, and 26% were civilians. Of the overall sample, n = 156 were part of the inactive control group (ICG), n = 55 in the active control group (ACG), and n = 118 in the intervention group (IG). Regarding the ICG, the mean age was M = 26.95 (SD = 8.74), 53% were male, and 24% were leaders. In the ACG, the mean age was M = 23.51 (SD = 2.64) and 56% were male. In the IG, the mean age was M = 36.99 (SD = 11.95), 44% were male, and 32% were leaders. The dropout rate for self-reported measures was 13% in the IG, 0% in the ACG, and 24% in the ICG. For physiological data, there were only a few dropouts for the ACG (PMR, 0%) and IG (MBI, 27%) but high in the ICG (72%). Motivating participants for physiological measurements in the ICG was challenging because investing time without participation was not attractive. Many dropouts resulted from incorrect measurements (e.g., due to chest strap being too loose) or poor compliance, e.g., moving or talking.

Procedure

To test our hypotheses, we used a 2 × 3 experimental mixed design (within-group repeated measures: pre- and post-intervention measures × between groups: (1) inactive control group [ICG], (2) active control group [ACG], and (3) intervention group [IG]). Participants completed a self-report questionnaire at time 1 (before the intervention) and time 2 (after the intervention). Physiological data were taken before and after each session.

The study was conducted in the German Armed Forces. The interventions were offered as part of the WHPP and were coordinated by professionals from the workplace health promotion team. Participation in the study was voluntary and based on written informed consent. There were no inclusion or exclusion criteria for this study. Since both the interventions took place within the military’s WHPP, both interventions can be classified as stress prevention measures. Any military member who wanted to strengthen their resources and promote their health could participate. For organizational reasons, only members of the same unit could participate together. Randomization of the allocation of individual participants was thus not possible. Therefore, units in which there was interest in participation were randomly assigned to the experimental conditions (similar to cluster randomization). Because participants could not choose the type of intervention, the risk of self-selection effects is low.

The IG received an MBI, referred to as mindfulness and resource-based worksite training (Krick et al., 2018). This training was designed as a multimodal program and is based on principles of MBSR and other worksite MBIs. Similar to MBSR and other MBIs, the present intervention encompassed (1) mindfulness practices, (2) mindful body stretching and movements, and (3) a cognitive education part. The primary aim of the MBI was to enhance the participants’ mindfulness skills. Kabat-Zinn’s concept of mindfulness and the concept of mindfulness skills served as the theoretical basis for the training (Baer et al., 2006; Kabat-Zinn, 1994). Moreover, we referred to positive psychology and resource activation (Seligman et al., 2006; Willutzki & Teismann, 2013), yoga (Saraswati, 2013), and acceptance commitment therapy (ACT; Bohus et al., 2013; Wengenroth, 2012). Each of the six sessions started with the mindful body stretching and movement part (i.e., focusing attention on body sensations during movements). The body exercises at the beginning of each session allow for better body awareness, facilitate mental quieting, and provide a relaxed start to the intervention. In the next cognitive education part, instructors provided knowledge about psychological functioning, resources, and the stress-eliciting process. In addition, this part included self-reflection exercises and group discussions to strengthen the perception of one’s resources and to further expand and even better use them. Each session ended with the mindfulness part including mindfulness practices, e.g., body scan and breathing awareness exercises. The training sessions were complemented by mandatory weekly homework, e.g., regular breathing exercises and self-reflection. In total, the training consists of six sessions each lasting 2 hr over 6 weeks. Similar to other MBIs in workplace settings, we used an MBI tailored to suit the specific needs and organizational constraints of the work environment, e.g., limited time resources. To strengthen acceptance and facilitate participation during regular working hours, we opted for a less time-consuming MBI format. Similar to Klatt et al. (2009), we chose an intervention with a length of six sessions. Klatt et al. (2009) as well as Krick and Felfe (2020) provided evidence for the benefits of a “lower-dose MBI” consisting of six sessions. To reduce the time burden on participants, the duration of each weekly session was shortened from 2.5 to 2 hr and the full-day retreat was omitted. Various studies and meta-analyses have indicated that the effectiveness of MBIs does not depend on the duration of the intervention, such as the number of weeks involved or the amount of class contact time (e.g., Virgili, 2015).

While the IG received the MBI, the ACG received PMR training originally developed by Jacobsen (1929). PMR is a somatic relaxation training program designed to help systematically prevent stress by tensing, relaxing, and observing specific muscle groups. When the tension is released, attention is drawn to the differences between tension and relaxation and the recognition of contrasts between both states. In this study, we used the shortened version by Joseph Wolpe consisting of six sessions (Helmer, 2008) and the guidelines by Bernstein and Borkovec (2004). The sessions were complemented by theoretical parts, e.g., addressing the stress process, the body’s reaction to stress, and relaxation processes in the body. PMR exercises were divided into three phases for each muscle group: (1) attention was focused on the respective muscle group and the current tension in this muscle group is perceived, (2) the muscle group is tensed, and the tension is maintained for 5 to 7 s. (3) The muscles are then relaxed again, and the focus remains on the muscle group for some time in order to perceive the current relaxation and the difference between tension and relaxation. Over the course of the sessions, the muscle groups were increasingly combined.

Both interventions were taught on-site at the department’s various training locations. Groups consisted of 8 to 15 participants. The setting for the ACG and IG was identical in length and course environment (e.g., same course length of 2 hr, classroom atmosphere with a teaching person in the front). Both the PMR intervention and MBI were instructed by qualified and experienced training personnel. To ensure the quality of the MBI, the following steps were taken: (1) Instructors followed a standardized manual; (2) trainers experienced the MBI themselves as participants before instructing it; (3) trainers completed a comprehensive 5-day advanced qualification course, covering theory and practical exercises related to the training; (4) ongoing supervision was maintained during and after implementation to ensure adherence; (5) the trainers possessed a solid foundation in mindfulness practice; and (6) all trainers held a minimum of a master’s degree in psychology. A similar procedure was obtained for PMR. The ICG received no intervention.

Although the preliminary results are mostly encouraging, upcoming studies need to consistently assess participant satisfaction to ensure that the interventions are acceptable to the target group (Goldberg et al., 2020). Knowledge of the acceptance and attendance rate will help practitioners select an appropriate intervention for the occupational group of interest and facilitate the implementation in the workplace (Jamieson & Tuckey, 2017). After the interventions were completed, participants therefore were asked to complete a training evaluation survey. In sum, n = 92 of the IG and n = 52 of the ACG filled out the evaluation questionnaire. All responses in the questionnaire and objective data were collected anonymously and were confidential. Data were used for research purposes only. Participants created a unique study identification code that was used throughout the study for anonymous data matching. All testing and training sessions occurred during participants’ duty day.

Measures

Mindfulness

Mindfulness was assessed using a short form of the FFMQ (Baer et al., 2008; Gu et al., 2016). The subscales were Observing (e.g., “I pay attention to sensations, such as the wind in my hair or sun on my face”), Acting with Awareness (e.g., “I do jobs or tasks automatically without being aware of what I’m doing”), Non-reacting (e.g., “When I have distressing thoughts or images I just notice them and let them go”), and Non-judging (e.g., “I tell myself I shouldn’t be feeling the way I’m feeling”). Items were rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = never or very rarely true to 5 = very often or always true. Higher scores reflect higher levels of mindfulness. Cronbach’s α for the subscales ranged from 0.71 to 0.86 at pre-test and from 0.77 to 0.87 at post-test. An overall score was calculated with Cronbach’s α 0.83 at pre-test and 0.87 at post-test.

Self-care

Due to reasons of parsimony, we assessed self-care by using a shortened form of the Health-oriented Leadership instrument by Franke et al. (2014). Self-care included three components: Health Awareness (8 items, e.g., “I realize when I arrive at my personal health limits,” Value of Health (3 items, e.g., “When making important decisions, I consider their impact on my health”), and Behavior (12 items, e.g., “I try to reduce my demands by optimizing my personal work routine, e.g., set priorities, care for undisturbed working, daily planning”). The response scale ranged from 1 = not at all true to 5 = completely true. An overall score was calculated. Cronbach’s α for the overall measure was 0.83 for self-care in the pre-test and 0.87 in the post-test. In addition to the overall measure, we looked at the “Health Promotion” sub-facet of the behavior component (9 items). Cronbach’s α was 0.72 (pre-test) and 0.77 (post-test).

Positive Affect

Positive affect reflects on emotions such as joy, interest, and enthusiasm (Tran, 2013). In this study, affect is seen as an emotional fluctuation that may change throughout situations and medium-term and longer periods of time. For the assessment of positive affect, the German version of the Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS) was used (Breyer & Bluemke, 2016; Watson et al., 1988). Participants were asked to rate the intensity of each experienced emotion (5 items, e.g., active, interested, excited, energetic, relaxed), during the past 2 weeks on a scale from 1 = very slightly or not at all to 5 = extremely. Cronbach’s α was 0.74 (pre-test) and 0.79 (post-test).

Psychological Strain

To assess strain, we used the irritation scale by Mohr et al. (2005). Irritation is described as symptoms of cognitive (3 items, e.g., “I have difficulty relaxing after work”) and emotional work-related strain (5 items, e.g., “I get irritated easily, although I don’t want this to happen”). The response scale ranged from 1 = not at all true to 5 = completely true. Cronbach’s α was 0.85 for the pre-test and 0.88 for the post-test, respectively.

Health Complaints

We assessed health complaints with a measure of common work-relevant physical and psychosomatic symptoms adapted from a scale developed by Mohr and Müller (2004). Participants were asked to assess whether they had recently experienced each of the physical and psychosomatic health complaints (13 items, e.g., “headache”; “eye problems”; “respiratory diseases”; “sleep disturbance”; “back, shoulder or neck pain”; “cardiopulmonary problems, hypertension”; “concentration problems”; “gastrointestinal problems”). The response scale ranged from 1 = not at all true to 5 = completely true. Cronbach’s α in this sample was 0.85 for pre- and 0.85 for post-test.

HRV and HR

We assessed HR and HRV data using the heart rate monitoring system Polar V800 and a chest strap. For the ACG and IG, data were measured before and after each session: Session 1 (S1, “pre measures and post measures”) to Session 6 after 6 weeks (S6, “pre measures and post measures”; Figure 1). In the ICG, data were collected before and after two assessment sessions (duration 2 hr each, assessment sessions took place 6 weeks apart, like both interventions). To obtain valid HR and HRV measures, participants were given some minutes to calm down before the assessment started and they were instructed not to speak and to sit quietly during the data collection procedure. Following the data collection procedure, all Polar V800 monitoring systems were synchronized, and raw data were exported using the Polar flow sync software. All measurement time points were assigned to each participant using an anonymous code. After exporting the raw data, they were imported into Kubios HRV (version 2.2, 2012, Biosignal Analysis and Medical Imaging Group, University of Kuopio, Finland, MATLAB). Samples were visually inspected for artifacts and then artifacts were corrected. Using Kubios HRV, two different time samples (5 min before [pre] and after each session [post]) were created for each raw data set using the time stamps of each data collection. To examine HR, we used the mean heart rate during pre-measurement and post-measurement. HR is measured in beats per minute (bpm). To examine HRV, rmssd (square root of the mean squared differences between successive normal heartbeats) is the most commonly used HRV indicator, measuring the variability in adjacent beat-to-beat differences and reflecting the vagal tone and parasympathetic activity (Kleiger et al., 2005; Laborde et al., 2017). Rmssd has previously been used in short-term HRV measurement (Burg et al., 2012; Segerstrom & Nes, 2007) and represents faster-moving beat-to-beat changes.

Data Analyses

First, we used 2 × 3 mixed design MANCOVAs (multivariate analysis of covariance; within-group repeated measures: pre- and post-intervention measures × between groups: (1) inactive control group [ICG], (2) active control group [ACG], and (3) intervention group [IG]). As some meta-analyses showed moderating effects of gender and age, but with mixed findings (Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020), we controlled both for gender and age. Considering important potential confounders such as age and gender is also highlighted by Hepner et al. (2022) and Christodoulou et al. (2020). Second, we conducted univariate 2 × 3 mixed design ANOVAs to test differences between groups over time for each effectiveness criterion separately (with time as a within-subject factor (pre, post) and condition (IG, ICG vs. ACG) as a between-subject factor). Significant group-by-time interaction effects were followed by planned contrasts comparing the three groups (IG, ICG, and ACG). Third, to assess changes over time within each group and ensure that group-by-time interaction effects could be attributed to improvements in the intervention group rather than deteriorations in the control groups, we conducted paired samples t-tests comparing pre- and post-scores for each group separately.

Concerning HR and HRV, recent studies showed changes from pre- to post-intervention. This overall intervention effect (from pre- to post-intervention) contains both short-term effects of the first session and the last session. In addition to pre- and post-intervention effects, we analyzed effects within the last session for all groups. Since the objective data for the ACG and IG were collected not only before and after the first and last session but also before and after each session, descriptive results on short-term changes within each session are also presented for these two groups as additional analyses. Effect sizes are reported by partial η2 (0.010 = small; 0.059 = medium; 0.138 = large; Cohen, 1988).

Results

Effectiveness of MBI on Self-reported Positive and Negative Health Indicators

The MANCOVA for self-reported health indicators showed an interaction effect (time by group), F(16, 608) = 6.64, p < 0.001, and partial η2 = 0.15. The univariate ANOVAs showed more improvement in mindfulness (H1a) in the IG than in the ACG and ICG (p < 0.001). This also applies to the sub-facets Act with Awareness, Observe, and Non-React. Regarding Non-judge, both the IG and the ACG showed an improvement, whereas the ICG did not show a change. Results also showed more increase in positive affect (H1b) and self-care (H1c) as well as more decrease in health complaints (H2b) in the IG than in the ACG and ICG (p < 0.001). Regarding strain (H2a), both IG and ACG showed a higher decrease in strain than the ICG (p < 0.001). As indicated by partial η2, effect sizes ranged from medium to large. Results of paired samples t-tests revealed significant improvements in all self-reported outcomes in the IG, with no significant changes in the ICG, while in the ACG strain decreased and Non-judge increased (Table 1). Results of the univariate ANOVAs and all time-by-group interaction effects and post hoc tests comparing each group are presented in Table 2. Additionally, means and standard deviations are shown in bar charts for self-reported health indicators (Fig. 2). These results support H1a/b/c and H2a but not H2b.

Effectiveness of MBI on Objective Health Indicators

Regarding objective physiological health indicators, the MANCOVA also showed an interaction effect (time by group), F(4, 352) = 10.66, p < 0.001, and partial η2 = 0.11. The univariate ANOVAs showed group-by-time interaction effects for HRV (H3a) and HR (H3b) regarding short-term effects within session 6 (HRV, F[2, 209] = 20.53, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.16; HR, F[2, 209] = 19.23, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.16; Table 2). Additionally, results also showed time-by-group interaction effects regarding pre-post intervention effects between Session 1 pre-intervention and Session 6 post-intervention for both HRV and HR (HRV: F[2, 209] = 37.88, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.27; HR: F[2, 209] = 8.77, p < 0.001; partial η2 = 0.08). Partial η2 ranged from medium to large. Comparing all groups, the IG showed a higher improvement in HRV and more decrease in HR compared to both control groups. There was no difference between ACG and ICG. Paired samples t-tests supported this finding. Comparing pre-test scores with post-test scores for each group separately revealed significant improvements in HRV and a decrease in HR for the IG, while ACG and ICG showed no significant changes in HRV and HR (Table 1, Fig. 3). These results support H3a and H3b.

Means and standard deviations of HRV (rmssd in ms) and HR (in beats per min) regarding the inactive control group, active control group, and intervention group. Note. “Intervention pre to post” (“complete intervention pre to post”): values assessed at pre-Session 1 (before the intervention) and post-Session 6 (after the intervention); “Session 6 pre-post”: values assessed before and after Session 6

Additional Analyses

We additionally analyzed group-by-time interaction effects on HRV and HR within each session comparing IG and ACG. Results revealed that participants of the IG showed significant higher short-term improvements in HRV in each session compared to the ACG (within Session 1: F[1, 153] = 21.61, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.12; within Session 2: F[1, 153] = 43.31, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.22; within Session 3: F[1, 153] = 39.11, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.20; within Session 4: F[1, 152] = 38.15, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.20; within Session 5: F[1, 153] = 29.52, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.16; within Session 6: F[1, 152] = 24.14, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.14). Means and standard deviations of HRV for each session are shown in Fig. 4.

Regarding HR, the results were similar. Results revealed that the IG showed significant higher short-term decreases in HR in each session than the ACG (within Session 1: F[1, 153] = 85.68, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.36; within Session 2: F[1, 153] = 58.18, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.28; within Session 3: F[1, 153] = 10.24, p < 0.01, partial η2 = 0.06; within Session 4: F[1, 152] = 18.44, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.11; within Session 5: F[1, 153] = 17.41, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.10; within Session 6: F[1, 152] = 20.58, p < 0.001, partial η2 = 0.12). The means and standard deviations of HR for each session are shown in Fig. 5.

Attendance, Acceptability, and Evaluation of the Intervention

Regarding the MBI, 35.3% attended all six sessions, 52.9% attended five sessions, and 11.8% participated in four out of the six sessions, overall indicating a high attendance rate. Regarding PMR, all participants attended all six sessions. Regarding the evaluation of the MBI, 83.7% stated that “the techniques taught are well-suited for reducing stress,” 94.9% enjoyed participating in the MBI sessions, and 92.4% were satisfied with the training overall. Regarding the PMR intervention (active control condition), 44.2% reported that “the techniques taught are well-suited for reducing stress,” 67.3% enjoyed participating in the PMR training sessions, and 76.9% were satisfied with the intervention.

Discussion

The present study aimed to clarify whether MBIs are effective in high-risk and “male-oriented” work contexts like the military. To examine the effectiveness of an MBI on positive and negative self-reported health indicators, an MBI was compared to an active control group, i.e., traditional stress management training (PMR) and an inactive control group. To provide stronger evidence, physiological objective health criteria complemented self-reported data.

Effectiveness on Self-reported Measures

Regarding self-reported positive health indicators, our findings provide support for nearly all hypotheses. In line with our expectations, results revealed that, in comparison to both control groups (active [PMR] and inactive), participants in the MBI improved their mindfulness skills (especially Acting with Awareness, Non-reacting, and Observing) and increased their self-care and positive affect. Regarding self-reported negative health indicators, results further revealed that both participants of MBI and PMR reported a decrease in psychological strain indicating that both interventions were equally effective in reducing strain. This was not the case for health complaints. MBI was shown to be superior to PMR and the inactive control group.

Effectiveness on Physiological Measures

Concerning objective health indicators, our findings showed that the MBI is superior to PMR and the inactive control group. Participants of the MBI reported improved HRV and reduced HR, while no such change was evident in the PMR group and the inactive group. MBI improved HRV and reduced HR regarding both short-term (within a session) and overall intervention effects. Both short-term effects within each session and overall intervention effects indicate an immediate effect on relaxation and a reduction in physiological arousal, but also an improved overall state of relaxation and improved self-regulation and resilience across training sessions. As increased HRV indicated, participants in the MBI showed improved cardiovascular and mental health, improved psychological flexibility and resilience, and better self-regulation (Brown et al., 2021; Christodoulou et al., 2020; Segerstrom & Nes, 2007; Shaffer & Ginsberg, 2017).

Theoretical Implications

Previous MBI studies in the military setting primarily examined soldiers in deployment or veterans, mostly focused on attention rather than self-reported or objective health indicators, used no active control group, and examined small sample sizes (e.g., Haase et al., 2016; Jha et al., 2010; Meland et al., 2015; Stanley et al., 2011). The present study contributes to occupational mindfulness research by closing these research gaps. First, our study extends the generalizability of previous results by examining a broader range of military personnel.

Second, from a theoretical perspective, our study also filled the evidence gap regarding the effectiveness of MBIs on health by examining both positive (asset-based) and negative (deficit-based) health indicators. Our study demonstrates that MBIs are effective for workplace health promotion, not only in social, health, and educational work settings but also in high-risk, “male-oriented” work contexts, such as the military. Our findings confirm previous research on the effects of MBI on mindfulness skills, self-care, positive affect, physical health, and psychological strain in the work context (Bartlett et al., 2019; Lomas et al., 2019; Vonderlin et al., 2020) and show that these positive effects also apply to the military context. Overall, this study provides a better understanding of the utility of MBIs in high-stress job contexts. It can be concluded that the MBI is also effective in high-risk and “male-oriented” job contexts with a specific culture (e.g., “toughness,” self-confidence) and traditional male gender norms such as suppressing the outward displays of expression of emotions (Jakupcak et al., 2014; Thompson & Pleck, 1986). The results of the present study extend previous findings of Krick and Felfe (2020) who showed the effectiveness of an MBI in increasing self-care, mindfulness, and HRV, and decreasing strain, health complaints, and HR in the police context.

Third, following several scholars (Brown et al., 2021; Morton et al., 2020; Virgili, 2015), it was important to include objective physiological health indicators for cross-validation of self-reported health indicators in the area of MBIs in the work context. Our results are in line with previous studies showing the effects of MBIs on HRV in the work context (Hunt et al., 2018; Joo et al., 2010; Krick & Felfe, 2020; Nijjar et al., 2014; Tung & Hsieh, 2019). Previous studies in the military context did not use objective health measures such as HRV and HR; thus, this study broadens previous evidence in the military context. The use of objective physiological health indicators complements findings from self-reported health effectiveness criteria and thus provides more robust evidence of the utility of MBIs in the military. As PMR is also supposed to decrease sympathetic arousal and indirectly increase parasympathetic activity (Groß & Kohlmann, 2021), our results regarding the PMR group are somewhat surprising. We have neither found a decreased HR nor improved HRV in the PMR group. In contrast to our findings, several studies showed positive effects of PMR on HR (e.g., in hypertensive clients, Manoppo & Anderson, 2019; healthcare professionals, Chaudhuri et al., 2014). However, our results are in line with previous inconsistent findings regarding PMR and HRV (e.g., Groß & Kohlmann, 2021; von Seckendorff, 2009, small sample sizes).

Fourth, several scholars have called for studies examining the effects of MBIs in the military setting using active control groups (Chen et al., 2022; Jha et al., 2017). The lack of an active control group makes it difficult to separate the effects caused by mindfulness skills and those attributable to other factors of the intervention. Including the active control group allowed us to examine whether MBIs are more or less superior to another traditional stress management intervention. By comparing MBI with both active and inactive control groups, we were able to control for extraneous variables that consistently might have affected results across interventions (e.g., expectancy effects). We thus provide stronger evidence of the effectiveness of MBIs and increase the internal validity of our findings. This study design allowed for more confident conclusions that mindfulness was the “active ingredient” in promoting health. As specifically studies on MBI and HRV mostly failed to use active control groups, this study strengthens the validity of the effects on self-reported measures, provides more clarity with regard to previously inconsistent findings in meta-analyses, and provides stronger evidence on the effectiveness of MBIs on HRV in the work context (Backlund, 2022; Rådmark et al., 2019).

In sum, this study further demonstrates the effectiveness of MBIs with an even more rigorous methodology (not only a passive control group, but also comparing MBI to a competing intervention, both self-reported and objective measures) and shows that the MBI is more effective than PMR in terms of promoting mindfulness, positive affect, and health behavior, as well as reducing physical complaints, making it superior to this traditional health intervention. In terms of stress reduction, both interventions were shown to be similarly effective confirming studies in the clinical context showing the effectiveness of PMR on distress (Jaya & Thakur, 2020; Sundram et al., 2016). However, our findings contradict theoretical assumptions that PMR may also lead to a reduction in physical health complaints. Our results showed that MBI and PMR did not equally reduce health complaints. Actually, the MBI was more effective in reducing psychosomatic health complaints than PMR or the inactive control group. It is conceivable that a mindful attitude (e.g., observing the body in an accepting manner and without overreacting) was more helpful than just tensing and relaxing the body to alleviate health complaints. Participants of the MBI showed a higher decrease in psychosomatic health complaints such as headache, sleep disturbance, concentration problems, or back pain from pre to post than the PMR group or inactive control group. Also contrary to our assumptions, the facet Non-judging also improved in the active control group. It is conceivable that the pure tensing and relaxing during PMR and focusing on the body may have also assisted in adopting a non-judgmental attitude.

Practical Implications

As Bonura and Fountain (2020) argued, it is questionable whether there is a fit between mindfulness teaching (e.g., mindful attitude) and military culture. Certain aspects of military culture (e.g., emphasis on “toughness,” self-reliance, and other traditional male gender norms such as avoiding the expression of vulnerable emotions; Jakupcak et al., 2014; Thompson & Pleck, 1986) may theoretically conflict with the mindful mindset and group norms commonly adopted in MBIs (e.g., acceptance, vulnerability, self-disclosure; Bonura & Fountain, 2020; Goldberg et al., 2020; Kabat-Zinn, 2013). It is further argued that military personnel may experience unique challenges with regard to the use of mindfulness exercises and may feel that these conflict with the “warrior ethos” (Bonura & Fountain, 2020; Cantrell & Dean, 2007; Tick, 2005). In contrast to these theoretical assumptions, we provide evidence that MBI is an effective intervention even for military personnel in a mainly “male-oriented” work context with a specific culture. In addition to the effectiveness of the MBI on health, we were also able to demonstrate a high acceptance of the intervention within the military sample. From a practical perspective, it is critical to know whether high-risk work contexts outside the health, social, and education sectors in particular benefit from MBIs. Because work stress is an unavoidable part of the job in these occupational contexts, it is particularly important to identify appropriate interventions to reduce stress and promote health. Employees from the health, social, and education sectors might be more receptive to mindfulness interventions than, for example, occupational contexts with more specific work cultures such as the military. By identifying and demonstrating the benefits of such appropriate interventions, practitioners can be encouraged to implement MBIs in these contexts to contribute to occupational health in high-risk job contexts. According to Bartlett et al. (2019), examining established stress management trainings in comparison to MBIs provides knowledge and a solid rationale for evaluating the comparative benefits of MBIs and thus supports organizational investment decisions.

While studies have shown that transformational and health-oriented leadership (i.e., staff-care) may improve self-care (Franke et al., 2014; Kaluza et al., 2021; Klebe et al., 2021), our results replicated the findings of Krick and Felfe (2020) and provided further evidence that MBIs are effective interventions to promote self-care. The implementation of MBIs and leadership may thus complement each other to optimally improve self-care.

Limitations and Directions for Future Research

Some limitations of this study need to be considered which lead to suggestions for future research. First, even though the results indicate medium to large improvements in our health criteria over time in the intervention group, the study design does not allow us to make any statements about long-term effectiveness. Our results indicate the effectiveness for the MBI period, but it is unclear whether the effects persist over time and how they evolve. Therefore, follow-up studies with pre-, post-, and follow-up measures investigating long-term effects are needed. Second, we were not able to implement individual randomization but used cluster randomization. As participants could not choose the type of intervention, their individual preferences could not have influenced the differences between experimental groups (e.g., self-fulfilling prophecy). Third, as participation was voluntary, an overall self-selection bias may have overestimated the individual pre-post effects (Janssen et al., 2018). Participants may have had a positive attitude or at least been open and particularly interested in stress prevention. Positive effects could in part have resulted from positive expectations. This overestimation, however, is more likely to occur with self-reported data than with objective physiological measures. This voluntary setting ensured a high degree of ecological validity, as the interventions were conducted in a real-life situation and as a workplace health promotion measure. Moreover, Krick and Felfe (2020) already showed evidence for the effectiveness of an MBI using a nonselective sample of police officers. Fourth, concerning the measurement of HRV, there are sometimes concerns about the validity of Polar monitors (Wallén et al., 2012); however, studies have repeatedly shown that they are as reliable as ECGs and are commonly used to measure HRV in healthy persons (Weippert et al., 2010). Although we would expect similar findings in other job contexts with a specific work culture, further studies should examine other specific “male-oriented” occupations and work contexts to further strengthen this evidence (e.g., firefighters). It should also be noted that only one-third of ICG provided psychophysiological assessments. Fifth, as half of our sample were female, it is conceivable that the organizational context is not as “male-oriented” as suggested. However, a male-oriented occupational role understanding is independent of gender, as our analyses showed (female M = 3.66, SD = 0.60 vs. male M = 3.70, SD = 0.69; t = 0.59, p = 0.559). Female and male participants did not differ in their “male-oriented” occupational role understanding. The term “male-oriented” here thus reflects more a military culture including an emphasis on “toughness,” self-confidence, and suppression of outward expression of emotions. Sixth, dropouts were not handled in the analyses (e.g., intent to treat). Therefore, the results represent outcomes for those who provided complete data.

Data Availability

Data not available for organizational data protection reasons.

References

Abendroth, J. (2021). The “Testpsychologie Psychische Fitness” of the psychological service of the German Armed Forces. In Federal Ministry of Defense (Ed.), Military Scientific Research Annual Report 2021 Defence Research for the German Armed Forces (pp. 124–125).

Amutio, A., Martínez-Taboada, C., Hermosilla, D., & Delgado, L. C. (2015). Enhancing relaxation states and positive emotions in physicians through a mindfulness training program: A one-year study. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 20(6), 720–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2014.986143

Anderson, N. D., Lau, M. A., Segal, Z. V., & Bishop, S. R. (2007). Mindfulness-based stress reduction and attentional control. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 14(6), 449–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.544

Backlund, A. (2022). The effects of mindfulness meditation on stress measured by heart rate variability: A systematic review. https://his.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1682768/FULLTEXT01.pdf

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Hopkins, J., Krietemeyer, J., & Toney, L. (2006). Using self-report assessment methods to explore facets of mindfulness. Assessment, 13(1), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191105283504

Baer, R. A., Smith, G. T., Lykins, E. L. B., Button, D., Krietemeyer, J., Sauer, S., Walsh, E., Duggan, D., & Williams, J. M. G. (2008). Construct validity of the five facet mindfulness questionnaire in meditating and nonmeditating samples. Assessment, 15(3), 329–342. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191107313003

Bartlett, L., Martin, A., Neil, A. L., Memish, K., Otahal, P., Kilpatrick, M., & Sanderson, K. (2019). A systematic review and meta-analysis of workplace mindfulness training randomized controlled trials. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 24(1), 108–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000146

Bernstein, D. A., & Borkovec, T. D. (2004). Entspannungs-Training: Handbuch der "progressiven Muskelentspannung" nach Jacobson (11. Aufl.). Leben lernen: Vol. 16. Pfeiffer bei Klett-Cotta.

Bohus, M., Lyssenko, L., Wenner, M., & Berger, M. (2013). Lebe Balance: Übungen für innere Stärke und Achtsamkeit (ungekürzte Ausgabe). TRIAS.

Bonura, K. B., & Fountain, D. M. (2020). From “Hooah” to “Om”: Mindfulness practices for a military population. Journal of Social, Behavioral, and Health Sciences, 14(1), 183–194. https://doi.org/10.5590/JSBHS.2020.14.1.13

Breyer, B., & Bluemke, M. (2016). Deutsche Version der Positive and Negative Affect Schedule PANAS. ZIS - GESIS Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences.

Brown, K. W., & Ryan, R. M. (2003). The benefits of being present: Mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(4), 822–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.4.822

Brown, L., Rando, A. A., Eichel, K., van Dam, N. T., Celano, C. M., Huffman, J. C., & Morris, M. E. (2021). The effects of mindfulness and meditation on vagally mediated heart rate variability: A meta-analysis. Psychosomatic Medicine, 83(6), 631–640. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000900

Burg, J. M., Wolf, O. T., & Michalak, J. (2012). Mindfulness as self-regulated attention. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 71(3), 135–139. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185/a000080

Cantrell, B., & Dean, C. (2007). Once a warrior: Wired for life. WordSmith.

Carlson, L. E., Speca, M., Faris, P., & Patel, K. D. (2007). One year pre-post intervention follow-up of psychological, immune, endocrine and blood pressure outcomes of mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) in breast and prostate cancer outpatients. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity, 21(8), 1038–1049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2007.04.002

Carmody, J., & Baer, R. A. (2008). Relationships between mindfulness practice and levels of mindfulness, medical and psychological symptoms and well-being in a mindfulness-based stress reduction program. Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 31(1), 23–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-007-9130-7

Chaudhuri, A., Ray, M., Saldanha, D., & Bandopadhyay, A. (2014). Effect of progressive muscle relaxation in female health care professionals. Annals of Medical and Health Sciences Research, 4(5), 791–795. https://doi.org/10.4103/2141-9248.141573

Chen, Y.-H., Chiu, F.-C., Lin, Y.-N., & Chang, Y.-L. (2022). The effectiveness of mindfulness-based-stress-reduction for military cadets on perceived stress. Psychological Reports, 125(4), 1915–1936. https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941211010237

Christodoulou, G., Salami, N., & Black, D. S. (2020). The utility of heart rate variability in mindfulness research. Mindfulness, 11(3), 554–570. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-019-01296-3

Clark, A. (2018). The efficacy of mindfulness based interventions for soldiers and veterans (Doctoral dissertation). https://digitalcommons.liu.edu/post_fultext_dis/3

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

Critchley, H. D., Eccles, J., & Garfinkel, S. N. (2013). Interaction between cognition, emotion, and the autonomic nervous system. Handbook of Clinical Neurology, 117, 59–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-444-53491-0.00006-7

Ditto, B., Eclache, M., & Goldman, N. (2006). Short-term autonomic and cardiovascular effects of mindfulness body scan meditation. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 32(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15324796abm3203_9

European Network for Workplace Health Promotion. (2018). The Luxembourg declaration 1997. http://www.move-europe.it/file%20pdf/2018%20Version%20Luxembourg_Declaration_V2.pdf

Franke, F., Felfe, J., & Pundt, A. (2014). The impact of health-oriented leadership on follower health: Development and test of a new instrument measuring health-promoting leadership. Zeitschrift für Personalforschung, 28(1-2), 139–161. https://doi.org/10.1177/239700221402800108

Goldberg, S. B., Riordan, K. M., Sun, S., Kearney, D. J., & Simpson, T. L. (2020). Efficacy and acceptability of mindfulness-based interventions for military veterans: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 138, 110232. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2020.110232

Groß, D., & Kohlmann, C.-W. (2021). Increasing heart rate variability through progressive muscle relaxation and breathing: A 77-day pilot study with daily ambulatory assessment. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11357. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph182111357

Gu, J., Strauss, C., Crane, C., Barnhofer, T., Karl, A., Cavanagh, K., & Kuyken, W. (2016). Examining the factor structure of the 39-item and 15-item versions of the Five Facet Mindfulness Questionnaire before and after mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for people with recurrent depression. Psychological Assessment, 28(7), 791–802. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000263

Haase, L., Thom, N. J., Shukla, A., Davenport, P. W., Simmons, A. N., Stanley, E. A., Paulus, M. P., & Johnson, D. C. (2016). Mindfulness-based training attenuates insula response to an aversive interoceptive challenge. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 11(1), 182–190. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsu042

Helmer, G. (2008). Progressive Muskelrelaxation nach Edmund Jacobson. In I. Kollak (Ed.), Burnout und Stress: Anerkannte Verfahren zur Selbstpflege für Gesundheitsfachberufe (pp. 91–110). Springer.

Hepner, K. A., Litvin, B. E., Newberry, S., Sousa, J. L., Osilla, K. C., Booth, M., Bialas, A., & Rutter, C. M. (2022). The impact of mindfulness meditation programs on performance-related outcomes: Implications for the U.S. Army. RAND Corporation https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RRA1522-1.html

Hülsheger, U. R., Feinholdt, A., & Nübold, A. (2015). A low-dose mindfulness intervention and recovery from work: Effects on psychological detachment, sleep quality, and sleep duration. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 88(3), 464–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12115

Hunt, M., Al-Braiki, F., Dailey, S., Russell, R., & Simon, K. A. (2018). Mindfulness training, yoga, or both? Dismantling the active components of a mindfulness-based stress reduction intervention. Mindfulness, 9(2), 512–520. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-017-0793-z

Jacobsen, E. (1929). Progressive relaxation. Univ. of Chicago Press.

Jakupcak, M., Blais, R. K., Grossbard, J., Garcia, H., & Okiishi, J. (2014). “Toughness” in association with mental health symptoms among Iraq and Afghanistan war veterans seeking Veterans Affairs health care. Psychology of Men & Masculinity, 15(1), 100–104. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031508

Jamieson, S. D., & Tuckey, M. R. (2017). Mindfulness interventions in the workplace: A critique of the current state of the literature. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 22(2), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000048

Janssen, M., Heerkens, Y., Kuijer, W., van der Heijden, B., & Engels, J. (2018). Effects of mindfulness-based stress reduction on employees’ mental health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 13(1), e0191332. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0191332

Jaya, P., & Thakur, A. (2020). Effect of progressive muscle relaxation therapy on fatigue and psychological distress of cancer patients during radiotherapy: A randomized controlled trial. Indian Journal of Palliative Care, 26(4), 428–432. https://doi.org/10.4103/IJPC.IJPC_236_19

Jha, A. P., Stanley, E. A., Kiyonaga, A., Wong, L., & Gelfand, L. (2010). Examining the protective effects of mindfulness training on working memory capacity and affective experience. Emotion, 10(1), 54–64. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0018438

Jha, A. P., Witkin, J. E., Morrison, A. B., Rostrup, N., & Stanley, E. A. (2017). Short-form mindfulness training protects against working memory degradation over high-demand intervals. Journal of Cognitive Enhancement, 1(2), 154–171. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41465-017-0035-2

Jha, A. P., Zanesco, A. P., Denkova, E., Rooks, J., Morrison, A. B., & Stanley, E. A. (2020). Comparing mindfulness and positivity trainings in high-demand cohorts. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 44(2), 311–326. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-020-10076-6

Johnson, D. C., Thom, N. J., Stanley, E. A., Haase, L., Simmons, A. N., Shih, P.-A. B., Thompson, W. K., Potterat, E. G., Minor, T. R., & Paulus, M. P. (2014). Modifying resilience mechanisms in at-risk individuals: A controlled study of mindfulness training in Marines preparing for deployment. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(8), 844–853. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13040502

Joo, H. M., Lee, S. J., Chung, Y. G., & Shin, Y. (2010). Effects of mindfulness based stress reduction program on depression, anxiety and stress in patients with aneurysmal subarachnoid hemorrhage. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society, 47(5), 345–351. https://doi.org/10.3340/jkns.2010.47.5.345

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (2013). Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness (Revised ed.). Random House Publishing Group https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/kxp/detail.action?docID=6088927

Kaluza, A. J., Weber, F., van Dick, R., & Junker, N. M. (2021). When and how health-oriented leadership relates to employee well-being - The role of expectations, self-care, and LMX. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 51(4), 404–424. https://doi.org/10.1111/jasp.12744

Kim, H.-G., Cheon, E.-J., Bai, D.-S., Lee, Y. H., & Koo, B.-H. (2018). Stress and heart rate variability: A meta-analysis and review of the literature. Psychiatry Investigation, 15(3), 235–245. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2017.08.17

Klatt, M. D., Buckworth, J., & Malarkey, W. B. (2009). Effects of low-dose mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR-ld) on working adults. Health Education and Behavior, 36(3), 601–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198108317627

Klebe, L., Klug, K., & Felfe, J. (2021). The show must go on: The effects of crisis on health-oriented leadership and follower exhaustion during Covid-19 pandemic. Zeitschrift für Arbeits- und Organisationspsychologie, 65, 231–243. https://doi.org/10.1026/0932-4089/a000369

Kleiger, R. E., Stein, P. K., & Bigger, J. T. (2005). Heart rate variability: Measurement and clinical utility. Annals of Noninvasive Electrocardiology, 10(1), 88–101. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-474X.2005.10101.x

Klug, K., Felfe, J., & Krick, A. (2019). Caring for oneself or for others? How consistent and inconsistent profiles of health-oriented leadership are related to follower strain and health. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2456. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02456

Klug, K., Felfe, J., & Krick, A. (2022). Does self-care make you a better leader? A multisource study linking leader self-care to health-oriented leadership, employee self-care, and health. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(11), 6733. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19116733

Krick, A., & Felfe, J. (2020). Who benefits from mindfulness? The moderating role of personality and social norms for the effectiveness on psychological and physiological outcomes among police officers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 25(2), 99–112. https://doi.org/10.1037/ocp0000159

Krick, A., Felfe, J., & Klug, K. (2019). Turning intention into participation in OHP courses? The moderating role of organizational, intrapersonal and interpersonal factors. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 61(10), 779–799. https://doi.org/10.1097/JOM.0000000000001670

Krick, A., Felfe, J., & Renner, K.-H. (2018). Stärken- und Ressourcentraining [Strength and resource training]: Ein Gruppentraining zur Gesundheitsprävention am Arbeitsplatz [A group training for health prevention in the workplace]. Hogrefe. https://doi.org/10.1026/02920-000

Krick, A., Felfe, J., & Renner, K.-H. (2020). Promoting health effectively and efficiently. In Federal Ministry of Defense (Ed.), Military Scientific Research Annual Report 2020 Defence Research for the German Armed Forces (pp. 66–67).

Krick, A., Wunderlich, I., & Felfe, J. (2022). Gesundheitsförderliche Führungskompetenz entwickeln. In A. Michel & A. Hoppe (Eds.), Handbuch Gesundheitsförderung bei der Arbeit: Interventionen für Individuen, Teams und Organisationen (pp. 213–231). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-28654-5_14-1