Abstract

Purpose

We aimed to describe the ethical issues encountered by health care workers during the first COVID-19 outbreak in French intensive care units (ICUs), and the factors associated with their emergence.

Methods

This descriptive multicentre survey study was conducted by distributing a questionnaire to 26 French ICUs, from 1 June to 1 October 2020. Physicians, residents, nurses, and orderlies who worked in an ICU during the first COVID-19 outbreak were included. Multiple logistic regression models were performed to identify the factors associated with ethical issues.

Results

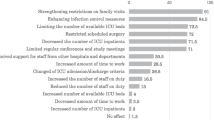

Among the 4,670 questionnaires sent out, 1,188 responses were received, giving a participation rate of 25.4%. Overall, 953 participants (80.2%) reported experiencing issue(s) while caring for patients during the first COVID-19 outbreak. The most common issues encountered concerned the restriction of family visits in the ICU (91.7%) and the risk of contamination for health care workers (72.3%). Nurses and orderlies faced this latter issue more than physicians (adjusted odds ratio [ORa], 2.98; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.87 to 4.76; P < 0.001 and ORa, 4.35; 95% CI, 2.08 to 9.12; P < 0.001, respectively). They also faced more the issue “act contrary to the patient's advance directives” (ORa, 4.59; 95% CI, 1.74 to 12.08; P < 0.01 and ORa, 10.65; 95% CI, 3.71 to 30.60; P < 0.001, respectively). A total of 1,132 (86.9%) respondents thought that ethics training should be better integrated into the initial training of health care workers.

Conclusion

Eight out of ten responding French ICU health care workers experienced ethical issues during the first COVID-19 outbreak. Identifying these issues is a first step towards anticipating and managing such issues, particularly in the context of potential future health crises.

Résumé

Objectif

Notre objectif était de décrire les enjeux éthiques rencontrés par les personnels de santé lors de la première éclosion de COVID-19 dans les unités de soins intensifs (USI) françaises, ainsi que les facteurs associés à leur apparition.

Méthode

Cette enquête multicentrique descriptive a été réalisée en distribuant un questionnaire à 26 unités de soins intensifs françaises, du 1er juin au 1er octobre 2020. Les médecins, les internes, le personnel infirmier et les aides-soignant·es qui travaillaient dans une unité de soins intensifs pendant la première éclosion de COVID-19 ont été inclus·es. Des modèles de régression logistique multiple ont été réalisés pour identifier les facteurs associés aux questions éthiques.

Résultats

Parmi les 4670 questionnaires envoyés, 1188 réponses ont été reçues, soit un taux de participation de 25,4 %. Dans l’ensemble, 953 personnes participantes (80,2 %) ont déclaré avoir éprouvé un ou des problèmes alors qu’elles s’occupaient de patient·es lors de la première éclosion de COVID-19. Les problèmatiques les plus fréquemment rencontrées concernaient la restriction des visites des familles dans les USI (91,7 %) et le risque de contamination pour les personnels de la santé (72,3 %). Le personnel infirmier et les aides-soignant·es étaient davantage confronté·es à ce dernier problème que les médecins (rapport de cotes ajusté [RCa], 2,98; intervalle de confiance [IC] à 95 %, 1,87 à 4,76; P < 0,001 et RCa, 4.35; IC 95 %, 2,08 à 9,12; P < 0,001, respectivement), tout comme ils étaient davantage confrontées à la question d’« agir contrairement aux directives médicales anticipées du/de la patient·e » (RCa, 4,59; IC 95 %, 1,74 à 12,08; P < 0,01 et RCa, 10,65; IC 95 %, 3,71 à 30,60; P < 0,001, respectivement). Au total, 1132 répondant·es (86,9 %) estimaient que la formation en éthique devrait être mieux intégrée à la formation initiale des personnels de santé.

Conclusion

Huit travailleuses et travailleurs de santé français·es des soins intensifs sur dix ont été confronté·es à des problèmes éthiques lors de la première éclosion de COVID-19. L’identification de ces enjeux est une première étape vers leur anticipation et leur gestion, en particulier dans le contexte d’éventuelles crises sanitaires futures.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Zhu N, Zhang D, Wang W, et al. A novel coronavirus from patients with pneumonia in China, 2019. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 727–33. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmoa2001017

Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. COVID-19 dashboard by the Center for Systems Science and Engineering (CSSE) at Johns Hopkins University (JHU). Available from URL: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html (accessed April 2023).

Greco M, De Corte T, Ercole A, et al. Clinical and organizational factors associated with mortality during the peak of first COVID-19 wave: the global UNITE-COVID study. Intensive Care Med 2022; 48: 690–705. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06705-1

Fernandes MI, Moreira IM. Ethical issues experienced by intensive care unit nurses in everyday practice. Nurs Ethics 2013; 20: 72–82. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733012452683

Beauchamp TL, Childress JF. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, 6th ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 2009.

Choi JS, Kim JS. Factors influencing emergency nurses’ ethical problems during the outbreak of MERS-CoV. Nurs Ethics 2018; 25: 335–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733016648205

Klar G, Funk DJ. Ethical concerns for anesthesiologists during an Ebola threat. Can J Anesth 2015; 62: 996–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-015-0416-x

Joebges S, Biller-Andorno N. Ethics guidelines on COVID-19 triage—an emerging international consensus. Crit Care 2020; 24: 201. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02927-1

Emanuel EJ, Persad G, Upshur R, et al. Fair allocation of scarce medical resources in the time of COVID-19. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 2049–55. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmsb2005114

Vergano M, Bertolini G, Giannini A, et al. Clinical ethics recommendations for the allocation of intensive care treatments in exceptional, resource-limited circumstances: the Italian perspective during the COVID-19 epidemic. Crit Care 2020; 24: 165. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-020-02891-w

Sprung CL, Cohen SL, Sjokvist P, et al. End-of-life Practices in European intensive care units. JAMA 2003; 290: 790–7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.290.6.790

Laurent A, Bonnet M, Capellier G, Aslanian P, Hebert P. Emotional impact of end-of-life decisions on professional relationships in the ICU: an obstacle to collegiality? Crit Care Med 2017; 45: 2023–30. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000002710

Damery S, Draper H, Wilson S, et al. Healthcare workers’ perceptions of the duty to work during an influenza pandemic. J Med Ethics 2010; 36: 12–8. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.2009.032821

Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: the conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009; 180: 853–60. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200810-1614oc

Cohen IG, Crespo AM, White DB. Potential legal liability for withdrawing or withholding ventilators during COVID-19: assessing the risks and identifying needed reforms. JAMA 2020; 323: 1901–2. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.5442

Persad G, Wertheimer A, Emanuel EJ. Principles for allocation of scarce medical interventions. Lancet 2009; 373: 423–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60137-9

Sandel MJ. Justice: What’s the Right Thing to Do? New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux; 2009.

Bryson GL, Turgeon AF, Choi PT. The science of opinion: survey methods in research. Can J Anesth 2012; 59: 736–42. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-012-9727-3

American Psychological Association. Morale. Available from URL: https://dictionary.apa.org/morale (accessed April 2023).

Ministère des Solidarités et de la Santé et Santé publique France. Tableau de bord COVID-19 Suivi de l’épidémie de COVID-19 en France. Available from URL: https://dashboard.covid19.data.gouv.fr/vue-d-ensemble?location=FRA (accessed April 2023).

Direction de la recherche, des études de l'évaluation et des statistiques. Nombre de lits de réanimation, de soins intensifs et de soins continus en France, fin 2013 et 2019. Available from URL: https://drees.solidarites-sante.gouv.fr/article/nombre-de-lits-de-reanimation-de-soins-intensifs-et-de-soins-continus-en-france-fin-2013-et (accessed April 2023).

Hosmer DW Jr., Lemeshow S, Sturdivant RX. Applied Logistic Regression, 3rd ed. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2013.

von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol 2008; 61: 344–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2007.11.008

World Health Organization. Maintaining essential health services: operational guidance for the COVID-19 context: interim guidance, 1 June 2020. Available from URL: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/332240 (accessed April 2023).

Fumagalli S, Boncinelli L, Lo Nostro A, et al. Reduced Cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit: results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation 2006; 113: 946–52. https://doi.org/10.1161/circulationaha.105.572537

Valley TS, Schutz A, Nagle MT, et al. Changes to visitation policies and communication practices in Michigan ICUs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2020; 202: 883–5. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.202005-1706le

Davidson JE, Jones C, Bienvenu OJ. Family response to critical illness: postintensive care syndrome–family. Crit Care Med 2012; 40: 618–24. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0b013e318236ebf9

Azoulay É, Curtis JR, Kentish-Barnes N. Ten reasons for focusing on the care we provide for family members of critically ill patients with COVID-19. Intensive Care Med 2021; 47: 230–3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-020-06319-5

Hugelius K, Harada N, Marutani M. Consequences of visiting restrictions during the COVID‐19 pandemic: an integrative review. Int J Nurs Stud 2021; 121: 104000. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.104000

Dragoi L, Munshi L, Herridge M. Visitation policies in the ICU and the importance of family presence at the bedside. Intensive Care Med 2022; 48: 1790–2. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00134-022-06848-1

Kennedy NR, Steinberg A, Arnold RM, et al. Perspectives on telephone and video communication in the intensive care unit during COVID-19. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021; 18: 838–47. https://doi.org/10.1513/annalsats.202006-729oc

Piscitello GM, Fukushima CM, Saulitis AK, et al. Family meetings in the intensive care unit during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2021; 38: 305–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049909120973431

Bruyneel A, Gallani MC, Tack J, et al. Impact of COVID-19 on nursing time in intensive care units in Belgium. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2021; 62: 102967. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iccn.2020.102967

Sperling D. Ethical dilemmas, perceived risk, and motivation among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020956376

Ruderman C, Tracy CS, Bensimon CM, et al. On pandemics and the duty to care: whose duty? Who cares? BMC Med Ethics 2006; 6: E5. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6939-7-5

Conseil national de l'Ordre des médecins. Article 48 - continuité des soins en cas de danger public. Available from URL: https://www.conseil-national.medecin.fr/code-deontologie/devoirs-patients-art-32-55/article-48-continuite-soins-cas-danger-public (accessed April 2023).

Légifrance. Décret n°93–221 du 16 février 1993 relatif aux règles professionnelles des infirmiers et infirmières *déontologie*. Available from URL: https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/loda/id/JORFTEXT000000179742/ (accessed April 2023).

Sokol DK. Virulent epidemics and scope of healthcare workers’ duty of care. Emerg Infect Dis 2006;12: 1238–41. https://doi.org/10.3201/eid1208.060360

Simonds AK, Sokol DK. Lives on the line? Ethics and practicalities of duty of care in pandemics and disasters. Eur Respir J 2009; 34: 303–9. https://doi.org/10.1183/09031936.00041609

Caillet A, Conejero I, Allaouchiche B. Job strain and psychological impact of COVID-19 in ICU caregivers during pandemic period. Anaesth Crit Care Pain Med 2021; 40: 100850. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accpm.2021.100850

Truog RD, Mitchell C, Daley GQ. The toughest triage — allocating ventilators in a pandemic. N Engl J Med 2020; 382: 1973–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejmp2005689

Breen CM, Abernethy AP, Abbott KH, Tulsky JA. Conflict associated with decisions to limit life-sustaining treatment in intensive care units. J Gen Intern Med 2001; 16: 283–9. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1525-1497.2001.00419.x

Rodríguez‐Arias D, Rodríguez López B, Monasterio‐Astobiza A, Hannikainen IR. How do people use ‘killing’, ‘letting die’ and related bioethical concepts? Contrasting descriptive and normative hypotheses. Bioethics 2020; 34: 509–18. https://doi.org/10.1111/bioe.12707

Ferrand E, Lemaire F, Regnier B, et al. Discrepancies between perceptions by physicians and nursing staff of intensive care unit end-of-life decisions. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2003; 167: 1310–5. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200207-752oc

Thompson DR. Principles of ethics: in managing a critical care unit. Crit Care Med 2007; 35: S2–10. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.ccm.0000252912.09497.17

Angus DC. Optimizing the trade-off between learning and doing in a pandemic. JAMA 2020; 323: 1895–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2020.4984

Tan DY, Ter Meulen BC, Molewijk A, Widdershoven G. Moral case deliberation. Pract Neurol 2018; 18: 181–6. https://doi.org/10.1136/practneurol-2017-001740

Miljeteig I, Forthun I, Hufthammer KO, et al. Priority-setting dilemmas, moral distress and support experienced by nurses and physicians in the early phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Norway. Nurs Ethics 2021; 28: 66–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020981748

Oerlemans AJ, van Sluisveld N, van Leeuwen ES, Wollersheim H, Dekkers WJ, Zegers M. Ethical problems in intensive care unit admission and discharge decisions: a qualitative study among physicians and nurses in the Netherlands. BMC Med Ethics 2015; 16: 9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-015-0001-4

Author contributions

Corentin Therond, Marion Douplat, Pierre Le Coz, and Antoine Lamblin conceived and designed the study. Corentin Therond supervised the conduct of the study and data collection, undertook recruitment of participating centres, and managed the data, including quality control. Bérengère Saliba-Serre provided statistical advice on study design and analyzed the data. Corentin Therond drafted the manuscript. Marion Douplat, Pierre Le Coz, Béatrice Eon, Fabrice Michel, Vincent Piriou, Bérengère Saliba-Serre, and Antoine Lamblin contributed substantially to its revision. Corentin Therond takes responsibility for the manuscript as a whole.

Acknowledgements

We thank Véréna Landel (Direction de la Recherche en Santé, Hospices Civils de Lyon) for her help in manuscript preparation. We also thank Quenot Jean-Pierre, Belaïd Bouhemad, Jean-Marc Tadie, Marc Laffont, Arnaud Winer, Fabienne Tamion, Didier Gruson, Thierry Seguin, Alain Mercat, Marc Leone, Matthieu Jeannot, Mael Hamet, Grégoire Muller, Henry Lessire, Elisabeth Gaertner, Sébastien Beague, Jean-Pierre Bedos, Renaud Blonde, Guillaume Schnell, Karim Chaoui, Christophe Guitton, Clément Dubost, Eric Meaudre, Pierre Bouzat, Jerome Morel, Emmanuel Futier, Emmanuel Samain, Claude Eccofey, Francis Remerand, Paul Michel Mertes, Rebecca Clement, Vanessa Chatelin, Michel Carles, Christophe Baillard, Jean-Luc Hanouz, Bertrand Debaene, Xavier Capdevila, Vincent Minville, Laurent Beydon, Bertrand Rozec, Mohamed Malti, and Antonin Huguerot.

Disclosures

The authors declare no potential conflict of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this manuscript.

Funding statement

Not applicable.

Data availability

The data sets used and/or analyzed in the present study are available upon reasonable request to the corresponding author.

Editorial responsibility

This submission was handled by Dr. Alexis F. Turgeon, Associate Editor, Canadian Journal of Anesthesia/Journal canadien d’anesthésie.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Therond, C., Saliba-Serre, B., Le Coz, P. et al. Ethical issues encountered by French intensive care unit caregivers during the first COVID-19 outbreak. Can J Anesth/J Can Anesth 70, 1816–1827 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02585-1

Received:

Revised:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12630-023-02585-1