Abstract

A global transformation of food systems is needed, given their impact on the three interconnected pandemics of undernutrition, obesity and climate change. A scoping review was conducted to synthesise the effectiveness of food system policies/interventions to improve nutrition, nutrition inequalities and environmental sustainability, and to identify double- or triple-duty potentials (their effectiveness tackling simultaneously two or all of these outcomes). When available, their effects on nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment were described. The policies/interventions studied were derived from a compilation of international recommendations. The literature search was conducted according to the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews. A total of 196 reviews were included in the analysis. The triple-duty interventions identified were sustainable agriculture practices and school food programmes. Labelling, reformulation, in-store nudging interventions and fiscal measures showed double-duty potential across outcomes. Labelling also incentivises food reformulation by the industry. Some interventions (i.e., school food programmes, reformulation, fiscal measures) reduce socio-economic differences in diets, whereas labelling may be more effective among women and higher socio-economic groups. A trade-off identified was that healthy food provision interventions may increase food waste. Overall, multi-component interventions were found to be the most effective to improve nutrition and inequalities. Policies combining nutrition and environmental sustainability objectives are few and mainly of the information type (i.e., labelling). Little evidence is available on the policies/interventions’ effect on environmental sustainability and women’s empowerment. Current research fails to provide good-quality evidence on food systems policies/interventions, in particular in the food supply chains domain. Research to fill this knowledge gap is needed.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Food systems impact both human and planetary health. Nearly one-third of the global population is experiencing some form of malnutrition (underweight, stunting, wasting, micronutrient deficiencies, overweight and obesity) (Abarca-Gómez et al., 2017). In particular, the prevalence of obesity has increased worldwide over the past 50 years, reaching pandemic proportions (Blüher, 2019). According to the latest figures by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), about 13% of the global adult population suffers from it (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017), and this number is expected to keep increasing to 17.5% by 2030 (Global Obesity Observatory, 2022). This trend is driven by a transition from traditional diets (with a high intake of fibre and grains) towards unhealthy and increasingly ultra-processed food consumption patterns (Baker et al., 2020; Browne et al., 2020), defined by a high consumption of meat, sugar, oils, and fats (Sproesser et al., 2019). Moreover, due to its link to nature, much of the environmental damage related to food systems occurs at the agricultural production stage (Campbell et al., 2017; OECD, 2021), considerably contributing to climate change and environmental degradation (e.g. deforestation, desertification, air, soil and water contamination) (Whitmee et al., 2015). Food systems are also acknowledged to cause 34% (25–42%) of man-made greenhouse gas emissions (GHGE) (Crippa et al., 2021) and 86% of biodiversity loss worldwide (Environment, 2021). Besides, food systems are also acknowledged to contribute to major nutritional inequities for undernutrition and obesity (Swinburn et al., 2019), as lower socio-economic groups are less likely to meet dietary recommendations and are more likely to have overweight or obesity (Løvhaug et al., 2022). Along the same line, vulnerable groups (e.g. migrant populations, Indigenous peoples, elderly populations, pregnant and lactating women, young children, youth…) are more susceptible to food insecurity, poor nutrition/unhealthy diets, and to developing diet-related non-communicable diseases (NCDs) (Devine & Lawlis, 2019; Schipanski et al., 2016). Therefore, the ways in which food is produced, processed, packaged, distributed, labelled, priced, consumed, or wasted represent key areas of potential intervention to reverse current unsustainable production and consumption trends.

The need for an urgent global transformation of current food systems is widely agreed by the scientific community (Swinburn et al., 2019; Willett et al., 2019), as they shall provide food security and nutrition for a world population projected to grow to nearly 10 billion by 2050 (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, 2017). One of the most promising and impactful ways to address nutrition and health issues, climate change and environmental degradation is by changing the way in which we produce and consume food. Because of their active and key role within the production, provision and consumption of food, women should be at the centre of such transformation (Benítez et al., 2020; Haby et al., 2016). Giner et al. (2022) highlighted that fostering gender inclusion can have positive impacts on the challenge of ensuring food security and nutrition for a growing population, in an environmentally sustainable way. Growing evidence suggests that certain population-level dietary shifts could simultaneously improve human health and environmental sustainability (Aleksandrowicz et al., 2016; Nelson et al., 2016; Perignon et al., 2017; Stewart et al., 2023; Willett et al., 2019). These shifts are necessary to attain Sustainable Healthy Diets, defined as dietary patterns that promote all dimensions of individuals’ health and wellbeing; have low environmental pressure and impact; are accessible, affordable, safe and equitable; and are culturally acceptable (FAO & WHO, 2019).

Policy-makers have an impactful role in the promotion of healthy and sustainable food practices (Hawkes et al., 2015; Lybbert & Sumner, 2012), as they are involved in the design and implementation of policies/interventions such as subsidies/incentives for farmers, multilateral agreements, mandatory food labelling, reformulation or taxes, among others. Hence, to transition to healthy and sustainable food systems, it is essential to understand the effectiveness of policies/interventions, and to identify their ability to simultaneously reduce the burden of the “Global Syndemic”, a concept was used by Swinburn et al. (2019) to describe the three ongoing pandemics affecting most people in every country and region worldwide: undernutrition, obesity and climate change (Swinburn et al., 2019). Based on this, triple-duty actions for governments were proposed to address them, given that these pandemics share common drivers and solutions. As these policies/interventions may drive positive changes in current food systems, a comprehensive overview of the latest evidence of their effectiveness is needed. While there is evidence on the effectiveness and potential of double- and triple-duty actions specifically targeting children (Venegas Hargous et al., 2023), the effectiveness of food systems policies/interventions across populations, disaggregated by gender or population groups, has not been systematically summarized.

2 Aim

The aim of this scoping review was to identify and synthesize the existing international evidence on the effectiveness of public sector food systems policies and interventions to improve nutrition, nutrition-related inequalities and environmental sustainability outcomes, and thus identify potential double- or triple-duty policies. A secondary objective was to identify the potential of such policies/interventions to address nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment.

3 Methods

3.1 Compilation of international policy recommendations and definition of policy (sub)domains and outcomes studied

In recent years, scientists, international institutions, global or regional organisations have published an increasing number of recommendations to create sustainable food systems (SFS), with a major focus on policy recommendations for governments. In a first step, a desk review was conducted to identify actions that governments can implement towards SFS. The recommendations were gathered and compiled from key reports, scientific papers and guidelines published by international organisations and academics. Once compiled, the recommendations were classified according to the identified food systems policy areas (divided in “domains” and “(sub)domains”), and were used during the search strategy as keywords for policies/interventions. More information about the search terms is available in Supplementary File 2.

The second step was to define the nutrition-related outcomes, nutrition-related inequalities and environmental sustainability outcomes that can be impacted by the prior-identified recommended food system policies/interventions. These primary outcomes were defined by taking into consideration the global health challenges depicted in the international reports, and approved by experts in public health nutrition (SV) and in environmental sustainability (WA). For nutrition-related inequalities, drawing on previously used definitions (McCartney et al., 2019), we use the term to indicate systematic differences in dietary quality between different population groups, linked either to their gender or to their socio-economic position. In addition, nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment were included as ‘secondary outcomes’, as they are not direct outcomes of the global Syndemic and not considered when assessing the double- or triple-duty potential of policies/interventions, but in a non-linear way they are simultaneously drivers and outputs common for the three pandemics. The term “nutritional vulnerabilities” refers to indicate those population groups that tend to be more susceptible to the double burden of malnutrition (i.e., children, pregnant/lactating women, ethnic minorities, Indigenous communities, farmers, elderly population). Women’s empowerment is used to indicate an increase of women’s access to control over the strategic life choices that affect them and to the opportunities that allow them fully to realize their capacities (Y.-Z. Chen & Tanaka, 2014). Lastly, two identified (sub)domains were also included as potential outcomes, as they can be impacted by other food systems policies/interventions: (1) food loss and waste and (2) food composition. A summary of the (sub)domains, the outcomes and their definitions are available in Table 1.

3.2 Protocol and registration

The scoping review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis guidance (PRISMA-ScR) using a checklist and explanation from Tricco et al. (2018). As appropriate for a scoping review, the protocol was developed iteratively, informed by the results of initial literature searches and in consultation with international food policy experts. The protocol (osf.io/g8p36) was registered with the Open Science Framework (OSF) on 21st December 2021, prior to undertaking the narrative synthesis.

3.3 Search strategy

The following research question was investigated: “What is the body of evidence on the effectiveness of food system policies and interventions to improve nutrition-related outcomes, nutrition-related inequalities and/or environmental sustainability outcomes?”. The term “food system policies” was used in the review to describe public sector policies/interventions impacting the production, processing, transport, consumption and waste of food. The term “sustainable food system” was described using the FAO concept described in 2018, as a food system that delivers food security and nutrition for all in such a way that the economic, social and environmental bases to generate food security and nutrition for future generations are not compromised (FAO & WHO, 2019). In addition, and when identified in the review, synergies (for policies/interventions with double or triple duty potential that have an effect on two or more outcomes) and trade-offs (when a policy/intervention has a positive effect on one outcome but a negative effect in another one) were also considered during the analysis. Given the enormous volume of literature, it was decided that the search would focus on evidence from the following types of peer-reviewed publications: scoping reviews, umbrella reviews, systematic literature reviews (with or without meta-analyses), narrative reviews and policy reviews.

The search strategy was piloted in May 2021 using the electronic database Scopus, within the policy domain of food supply chains. Based on the piloting, parameters such as the timeline were adjusted and the definitive literature search was conducted in July 2021 across four electronic databases (Scopus, Medline, Embase, Web of Science). The search strategy was created using Scopus as the reference database, and terms and keywords were adapted to be applied in the other databases. More information about the search terms is available in Supplementary File 2. In addition to database searches, seven additional papers were manually added based on co-authors suggestions of online published reviews on the topic.

3.4 Eligibility criteria

Reviews had to assess the impact of food system policies/interventions on nutrition‐related outcomes, nutrition-related inequalities and/or environmental sustainability outcomes in order to be eligible. The detailed set of inclusion and exclusion criteria applied is given in Table 2.

3.5 Data selection

All search results were downloaded as reference files and assembled as a final library using Zotero Reference Manager. Duplicates were removed across databases. The remaining results were screened in accordance with PRISMA guidelines: first at title and abstract level, then at full-text level.

For the title screening, the reviews identified through the database search were exported to the online bibliographic database Rayyan (Qatar Computing Research Institute, Data Analytics, Doha, Qatar). Title and abstract screenings were conducted by one researcher (CB). Any duplicates that were not identified by Zotero’s duplicate removal were manually removed. The screening phase entailed careful reading of each individual title and abstract, and then, based on predetermined inclusion criteria the decision whether to include a review or not was made by one researcher (CB). A second researcher (VG) randomly selected 10% of the total number of abstracts identified, and independently screened the title and abstract of the reviews. Disagreements were solved by discussion and assessment by a third researcher (SV). If there was any remaining doubt about eligibility, the study was included in the next step. If after the screening process the eligibility of certain studies remained unclear, it was solved by a discussion with the third researcher (SV).

Full-text reviews of potentially relevant publications were located and appraised by one researcher (CB) to select those meeting the inclusion criteria. The second researcher (VG) randomly selected 10% of the total number of full-text articles identified and independently applied the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were solved by discussion and assessment by the third researcher (SV). If no full text was available, the respective review was excluded from analysis but was included in a list of unobtainable articles [Supplementary File 3].

3.6 Data extraction

Data extraction of all included reviews was conducted by the first author (CB) in an Excel file using a prior defined table, which included the following fields: year, author(s), review type, review aim, study details (population targeted, geographical locations, setting), types of policies/interventions [according to the policy domains and (sub)domains], outcomes measured (primary outcomes, secondary outcomes – if any, double/triple duty potential, synergies and/or trade-offs identified – if any), type of impact (positive, neutral, negative, inconsistent/mixed) on primary and secondary outcomes, quality of the review and additional comments. For the final stage of full text screening, in case of uncertainty, full texts were read and screened by the third author (SV).

3.7 Synthesis of results

A meta-analysis was not possible due to the broad scope of this review and the great variability in analysed policies/interventions, outcomes and quantitative outputs which were not available in a consistent way across reviews. Instead, a qualitative summary of findings was generated using thematic analysis and narrative synthesis. Results are presented by policy (sub)domain and by outcome as defined in Table 1. The summarised information gathered per policy (sub)domain allows the reader to understand the evidence available by policy/intervention areas.

In terms of effectiveness, whenever possible, the overall direction of results for each policy/intervention was described as follows:

-

a

Positive (⇧): the effect of the policy/ intervention contributed to reduce undernutrition and/or obesity/NCDs, to improve nutrition/healthy diets, environmental sustainability, and/or women’s empowerment, and/or to reduce inequalities (socio-economic, gender, vulnerable populations) in diets;

-

b

Neutral (⇔): there was no statistical difference in effects in outcomes after the policy/intervention implementation, or no effects of the policy/intervention were detected;

-

c

Negative (⇩): the effect of the policy/intervention contributed to increase undernutrition and/or obesity/NCDs, to deteriorate nutrition/diets or environmental sustainability and/or women’s empowerment, or to increase inequalities (socio-economic, gender, vulnerable populations) in diets;

-

d

Inconclusive/mixed (~): the results were inconsistent (mixed results) across the reviews, so conclusions could not be reached in this review.

-

e

No data (0): there is a gap in the literature.

In the cases where final result was “inconclusive/mixed” additional explanations gathered from the results of each review are given to clarify the different effects identified, and potential explanations for each direction.

There was not a set magnitude or intensity of the results defined that must be exceeded for a review of interventions to be considered positive, and the overall decision was made based on the most common reported effect of the policies/interventions and, when results were even, on the reviews that were assessed of high or moderate quality, as explained below.

3.8 Assessment of methodological quality

The methodological quality of included systematic reviews was assessed by one author (CB) using AMSTAR-2, a Measurement Tool to Assess Reviews (Shea et al., 2017). The AMSTAR-2 is a 16-item validated quality assessment tool that allows for inclusion of both randomized and observational studies and as such, is not intended to be scored. For each AMSTAR-2 criterion, a score of one was assigned if ‘yes’ was the response, otherwise a score of zero was assigned. A study-specific global score, ranging from zero to sixteen, was calculated by summing up scores across all flaws. The quality of a 10% random selection of the total number of articles was evaluated by the second researcher (VG) using AMSTAR-2, randomly selected. Any possible disagreement at this stage was solved by discussion and assessment by a third researcher (SV).

As suggested by Shea et al. (2017), we consider as critical flaw all the indicators proposed by the guidelines, but we decided to count as a critical weakness (instead of just weakness) the criterion 16 (“Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review?”) as this could be an important aspect to take into account based on the increasing evidence of commercial influences on the development of policies (Lee et al., 2022; Mialon, 2020). The quality appraisal was focused at the review level and not at the individual study level. The quality assessment of each review, based on the scores shown in Table 3, was used to interpret the results of reviews when synthesized and in the formulation of conclusions. Reviews were not included or excluded based on quality.

4 Results

4.1 Compilation of international policy recommendations and definition of policy (sub)domains and outcomes studied

A total of 23 global reports, papers and guidelines providing a complete representation of SFS-related policy recommendations for governments were compiled by the first (CB) and the last authors (SV). All the recommendations identified were then classified by policy area, and grouped to define two policy domains and ten (sub)domains. The domain of “food supply chains” included: (1) food production, (2) food storage, processing, packaging and distribution, (3) food loss and waste, and (4) food trade and investment agreements. The domain of “food environments” included: (1) food composition, (2) food labelling, (3) food promotion, (4) food provision, (5) food retail and (6) food prices. The definition of each (sub)domain is included in Table 1. A summary of the number of policy recommendations and their sources is included in Supplementary File 1.

4.2 Data selection and extraction

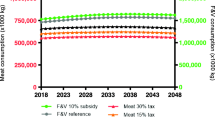

Initially, 16,221 articles were identified, of which 7000 were removed as duplicates. From the initial 9,228 records screened, 416 were selected for the assessment of eligibility at full-text level. A total of 196 reviews met the inclusion criteria. The agreement between the reviewers during the initial screening of titles and abstracts was fair (87%), while the agreement rate at the full-text stage was excellent (93%). All disagreements were solved by a third researcher (SV). The screening process and results are depicted in Fig. 1, and detailed information on the reasons for exclusion of each review is available in the Supplementary File 3.

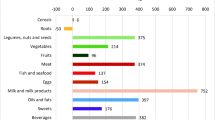

This scoping review covered worldwide reviews that varied in intervention types, geographic location, setting, population group, study designs, and methods of measuring outcomes. The number of reviews evaluating each policy (sub)domain is presented in Fig. 2. The total number is higher than 196 because 35 reviews included more than one policy (sub)domain and 10 focused on multi-component interventions that allowed for separate (sub)domain analysis. However, 15 reviews on multi-component interventions did not allow for separate (sub)domain analysis.

4.3 Overall summary of the results and quality assessment

A high-level overview of the policies/interventions studied by (sub)domain and their potential effectiveness for the outcomes identified are shown in Table 4. Further details of the characteristics of the included reviews (geographic locations, population studied, settings, objectives, conclusions, number of studies included in each review) can be found in the Supplementary File 3. The agreement between the reviewers for the quality was fair (60%). Disagreements were resolved by the third reviewer (SV). The total quality scores of the reviews included in this scoping review ranged from 2 to 16: 7 reviews were considered as high quality, 36 as moderate, 72 as low, and 81 as critically low quality.

4.4 Food supply chains

We identified 46 reviews analysing policies/interventions within the food supply chains domain. Undernutrition was the most studied outcome (n = 38), followed by nutrition/healthy diets (n = 33). For outcomes related to environmental sustainability (n = 10) and nutrition inequalities (n = 8), the evidence remains scarce. A total of 34 reviews analysed the effects of policies/interventions on nutritionally vulnerable populations, while women’s empowerment was included in 8 reviews. More information on study settings, geographic location, parameters measured, and summary tables of each review included on the food supply chains domain is available in the Supplementary File 4.

4.5 Food production

The policies/interventions analysed in the reviews included: agroforestry interventions, home/school gardens, nutrition-sensitive agricultural (NSA) interventions, bio-fortification, crop diversification, intercropping, integrating crop and livestock, livestock production and management, specific management strategies to reduce environmental sustainability challenges (e.g. soil erosion, land and water use, biodiversity loss…), agricultural input subsidies, output price policies and urban agriculture programmes.

4.5.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

The reviews describing the impacts of food production policies/interventions on undernutrition and nutrition/healthy diets reported an overall positive effectiveness, particularly for agroecology, crop diversification, bio-fortification and home/school gardens. Similarly, those reviews analysing the impact on environmental sustainability showed overall positive effects, in particular for no-tillage agriculture interventions. However, from the reviews analysing the effects on obesity/NCDs, one showed positive results (Prescott et al., 2020), two found no effects (Haby et al., 2016; Pullar et al., 2018) and five did not find enough data (Bird et al., 2018; Browne et al., 2020; Holley & Mason, 2019; Naik et al., 2019; Walls et al., 2018). Those including nutrition inequalities in their analysis did not find consistent results either (Black et al., 2017; Haby et al., 2016; Holley & Mason, 2019; Naik et al., 2019).

4.5.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

Most reviews that reported results on nutritionally vulnerable populations showed an overall positive impact on their nutrition status, except for three that reported insufficient or mixed effects on children, and lactating/pregnant women (Smith et al., 2013; Black et al., 2017; J. L. Finkelstein et al., 2019). All the interventions incentivising garden-based programmes in schools found consistent positive effects among children. From the reviews analysing the impact of policies/interventions on women’s empowerment, five found positive results (Castle et al., 2021; Feliciano, 2019; Pandey et al., 2016; Sharma et al., 2021; Walls et al., 2018), one found inconsistent/mixed results (Kadiyala et al., 2014) and another found no data to determine effects (Wordofa & Sassi, 2020).

4.5.3 Food production: synergies and trade-offs

Double-duty policies/interventions were identified in some reviews (Castle et al., 2021; Feliciano, 2019; Kadiyala et al., 2014; Sharma et al., 2021). NSA, crop diversification and agroforestry interventions may have a positive effect both for undernutrition and environmental sustainability (soil erosion), and are potentially beneficial for women’s empowerment. School garden interventions have a positive impact on both undernutrition (micronutrient deficiencies) and nutrition/healthy diets (diet intake and variety) among children (Masset et al., 2012). Two trade-offs were identified across outcomes: (1) water desalination strategies can increase GHGE despite being beneficial for freshwater use (El Chami et al., 2020); (2) school garden-based interventions may increase food waste, despite improving nutritional outcomes (Prescott et al., 2020).

4.6 Food storage, processing, packaging and/or distribution

The vast majority of the reviews included in this sub(domain) analysed policies/interventions related to food processing, most of them on food fortification (increasing the nutrient value of foods by fortifying them with vitamins and minerals) or supplementation, either mandatory or voluntary, and one on source of the ingredients replacement towards organic products. One review (Browne et al., 2020) also included food distribution interventions, focusing on improved food and water supply (transport) to under-served community settings. Food packaging interventions was evaluated in one review that included changes in types of packaging and in the estimations of food portion sizes (Almiron-Roig et al., 2020). None of the reviews focused on food storage policies/interventions.

4.6.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

Most of the reviews on the impacts of policies/interventions on undernutrition, focusing on micronutrient deficiencies (mainly on vitamin A, iron, iodine, folate and zinc; and less commonly on vitamin D and calcium), stunting, wasting and birthweight, found overall positive effects (Almiron-Roig et al., 2020; Best et al., 2011; Browne et al., 2020; Das et al., 2013; Dewi & Mahmudiono, 2021; Iglesias Vázquez et al., 2019; Menon & Peñalvo, 2019a, 2019b; Mithra et al., 2021; Morilla-Herrera et al., 2016; Poscia et al., 2018; Pratt, 2015; Tam et al., 2020). Nutrition/healthy diets was assessed in reviews describing the effects of policies/interventions related to food fortification programmes and food packaging and portion size, showing overall positive effects (Browne et al., 2020; Campos Ponce et al., 2019; Morilla-Herrera et al., 2016; Poscia et al., 2018), while the effects on obesity/NCDs from distribution and food processing interventions remain mixed/inconsistent (Browne et al., 2020; Menon & Peñalvo, 2019b; Poscia et al., 2018; Thomson et al., 2018). The review on ingredients replacement found positive effects on environmental sustainability (Takacs & Borrion, 2020). From the reviews evaluating nutrition inequalities associated to food fortification programmes, one found positive effects (Iglesias Vázquez et al., 2019) while the other, more detailed and of higher quality, showed mixed results (Thomson et al., 2018).

4.6.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

The majority of the reviews analysing effects on nutritionally vulnerable populations reported an overall positive impact on their nutrition status, except for three that reported no effects on children (Gera et al., 2019; Pachón et al., 2015; Sguassero et al., 2012), and one that found lack of evidence for mandatory fortification in HICs (Thomson et al., 2018). None of the reviews analysed the impact on women’s empowerment.

4.6.3 Food storage, processing, packaging and distribution: synergies and trade-offs

One review (Poscia et al., 2018) suggested that micronutrients supplementation could be beneficial to prevent undernutrition and obesity/NCDs in elderly populations, as it ameliorates the intake of protein and energy, improving weight-related outcomes. For this (sub)domain, no trade-offs were identified.

4.7 Food loss and waste

None of the reviews evaluated in isolation the effectiveness of policies/interventions implemented to tackle food loss and/or waste. Only one review of critically low quality (Takacs & Borrion, 2020), analysed the impact of mandatory food waste prevention measures undertaken in catering settings, involving the optimisation of the planning system to reduce overproduction, and the donation of leftovers to food banks. The results showed an overall positive effect of such interventions on environmental sustainability parameters, but with lower improvement potential when compared to other interventions, such as the replacement of ingredient sources (included under food processing).

4.7.1 Food waste as an outcome

Food waste was evaluated as an outcome in some reviews. Within food prices, subsidy programmes (vouchers) in LMICs may be a strategy to reduce waste during the highest seasons of food insecurity (Urgell-Lahuerta et al., 2021). Within food provision, some policies/interventions to improve children or adults’ dietary diversity in public settings have shown to increase food waste (Brennan & Browne, 2021; Metcalfe et al., 2020; Prescott et al., 2020). However, a similar intervention was linked to a reduction of the food wasted (Mansfield & Savaiano, 2017).

4.8 Food trade and investment

The food trade policies/interventions analysed in the reviews included: global trade policies, regional trade agreements, output price policies (OPP), trade liberalisation policies (such as tariffs removal, border liberalisation, elimination of quantitative restrictions, reduction of input and production subsidies, liberalisation of agricultural markets) and public distribution system policies (PDSP).

4.8.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

Most of the reviews describing the effect of trade on undernutrition found overall negative impacts of current food trade policies, reporting that the main regulatory framework of such policies focuses on economic growth (Kadiyala et al., 2014; Loewenson et al., 2010), increasing the prices of food commodities leading to higher numbers of undernutrition in some areas (Kadiyala et al., 2014; Loewenson et al., 2010). In this line, some reviews linking trade agreements with nutrition/healthy diets, reported an increase of the intake of unhealthy products [i.e., processed foods and sugar-sweetened beverages (SSBs)] (Barlow et al., 2017; Turner et al., 2019). However, the overall effects of such policies on nutrition/healthy diets remain mixed, as other reviews included found positive or mixed effects (Hyseni, Atkinson, et al. 2017; Naik et al., 2019). The reviews reporting the effects of trade policies on obesity/NCDs did not find enough data, except for one that reported negative impacts (Barlow et al., 2017). Similarly, those reviews evaluating the nutrition inequalities of trade policies/interventions found negative effects across socio-economic groups (Dangour et al., 2013; Naik et al., 2019). No data was found on environmental sustainability outcomes (Haby et al., 2016).

4.8.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

The reviews including nutritionally vulnerable populations (i.e., children, women, farmers) reported mixed results (Dangour et al., 2013; Kadiyala et al., 2014; Turner et al., 2019). Two reviews analysed the impact of trade policies on women’s empowerment, one found mixed results (Kadiyala et al., 2014),whereas the other reported an overall negative impact, explaining that globalisation-related economic and trade policies have been associated with shifts in women's occupational roles and resources that contribute to documented poor nutritional outcomes (Loewenson et al., 2010).

4.8.3 Food trade and investment: synergies and trade-offs

No synergies or trade-offs were identified.

5 Food environments

We identified 164 reviews analysing policies/interventions on food environments. Nutrition/healthy diets was the most studied outcome (n = 154), followed by obesity/NCDs (n = 72) and nutritional inequalities (n = 11). The evidence remains scarce on environmental sustainability outcomes (n = 3). The effects on nutritionally vulnerable populations were analysed on 34 reviews, while none of the reviews analysed the impacts of policies/interventions on women’s empowerment. More information on study settings, geographic locations, parameters measured, and summary tables of each review included on the food environments domain is available in the Supplementary File 5.

5.1 Food composition

The policies/interventions analysed included food reformulation strategies, either mandatory or voluntary. Most of the reviews analysed the impact of general reformulation strategies for food high in fat, sugar and salt (HFSS) or calories, two focused on sodium (Hyseni, Elliot-Green, et al., 2017; Santos et al., 2021), two on trans-fatty acids (TFA) (Hyseni, Bromley, et al., 2017b) and one on sugar reformulation strategies (von Philipsborn et al., 2019). Only three reviews allowed to make a distinction on the differences in effectiveness between mandatory and voluntary reformulation, concluding that mandatory reformulation generally achieves larger reductions in population-wide intake consumption than voluntary initiatives (Hyseni, Elliot-Green, et al., 2017; Hyseni, Bromley, et al., 2017; Hendry et al., 2015).

5.1.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

The reviews describing the effect of food reformulation on undernutrition did not find any evidence (Browne et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2018). All the reviews (n = 15) described the effect of composition on nutrition/healthy diets, linking reformulation strategies with intake of specific nutrients (i.e., sodium, sugar, TFA, calories, fibre, or several HFSS nutrients simultaneously) or specific foods (i.e., whole grains, processed foods, sugar sweetened milks), and reported intake reductions of those nutrients/foods showing overall positive effects. From the reviews analysing the effects on obesity/NCDs, two found positive results (Gressier et al., 2021; Hyseni, Elliot-Green, et al., 2017) while the rest found no evidence (Bonab et al., 2020; Browne et al., 2020; Hyseni, Bromley, et al., 2017; Løvhaug et al., 2022). The review aiming to analyse their impact on environmental sustainability did not find enough information (Temme et al., 2020). Socio-economic inequalities linked to reformulation were analysed in three reviews that found no data (Hendry et al., 2015; Løvhaug et al., 2022; Temme et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2018), while one found positive effects concluding that mandatory reformulation was equitably distributed among population groups (Hendry et al., 2015). Regarding gender inequalities, no evidence was available (Gressier et al., 2021).

5.1.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

With regard to nutritionally vulnerable populations (i.e., children, women, low-income, Indigenous populations), two reviews reported positive results (Bonab et al., 2020; Browne et al., 2020) while one reported no effect (Thomson et al., 2018). None of the reviews analysed the impact of reformulation on women’s empowerment.

5.1.3 Food composition: synergies and trade-offs

No synergies or trade-offs were identified.

5.1.4 Food composition as an outcome

Food composition was evaluated as an outcome in some reviews related to food labelling (Cawley & Wen, 2018; Hillier-Brown et al., 2017; Rincón-Gallardo Patiño et al., 2020; Russo et al., 2020; Shangguan et al., 2019; Sisnowski et al., 2017) showing positive impacts of front-of-pack nutrition labelling (FOPNL) and menu labelling on food reformulation by the industry.

5.2 Food labelling

The policies/interventions analysed included different food labelling strategies, overall divided into FOPNL (n = 26) and menu labelling (n = 15), either mandatory or voluntary. Reviews described the effectiveness of labels such as nutrition claims, calorie or sugar labelling, warning messages/signs or graphical depictions (i.e., the health star rating, traffic light labelling, high sugar symbol labels, carbon labelling, etc.), but some reviews did not specify the type of food labelling intervention evaluated. Only four reviews (Rincón-Gallardo Patiño et al., 2020; Shangguan et al., 2019; Temme et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2018) allowed to differentiate between mandatory labelling policies and voluntary strategies, finding mixed results as some authors suggested that information-based policies/interventions have been found to be much less effective than other influencing directly the structure of food environments (Temme et al., 2020), while others suggested that no significant heterogeneity was identified by voluntary or legislative approaches to food labels (Shangguan et al., 2019).

5.2.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

The reviews aiming to describe the effect of food labelling on undernutrition did not find sufficient data (Moran et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2018). Most reviews described the effect of labelling on nutrition/healthy diets, linking consumer’s information strategies with diet intake or food purchase (in particular foods or beverages high in energy, fats or sugar), and reported overall positive impacts. The majority of the reviews aiming to report the effects of labelling on obesity/NCDs did not find sufficient information, and only two found positive effects (S. Cawley & Wen, 2018; Roberts et al., 2019). From the reviews analysing the impact of labelling on environmental sustainability, two suggested an overall positive effects (Potter et al., 2021; Takacs & Borrion, 2020), while one found no evidence (Temme et al., 2020). The reviews evaluating nutrition inequalities associated to labelling showed overall negative impacts of these interventions as their effects varied across populations groups. Most of the reviews suggested that labels had positive effects of greater magnitude among participants with higher incomes and/or that females were influenced more positively than males (Cecchini & Warin, 2016; Feteira-Santos et al., 2020; Lobstein et al., 2020; Potter et al., 2021; Temme et al., 2020; Thomson et al., 2018), whereas one found mixed results (Hartmann-Boyce et al., 2018) and one did not find differences across socio-economic groups (Løvhaug et al., 2022).

5.2.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

With regard to nutritionally vulnerable populations, two reviews reported mixed results (Sisnowski et al., 2017; Thomson et al., 2018), one did not find enough data (Vargas-Garcia et al., 2017), and one reported positive effects (Browne et al., 2020). None of the reviews analysed the impact of food labelling on women’s empowerment.

5.2.3 Food labelling: synergies and trade-offs

For this (sub)domain, no synergies were reported. However, a potential trade-off identified was that the positive effects of labelling on diet intake/food purchase were of greater magnitude among participants with higher incomes and among women, suggesting an overall negative impact on inequalities (Cecchini & Warin, 2016; Feteira-Santos et al., 2020; Lobstein et al., 2020; Potter et al., 2021; Temme et al., 2020). This negative effect was also reported among children (Thomson et al., 2018).

5.3 Food promotion (marketing)

The policies/interventions analysed in the reviews included marketing restrictions of unhealthy foods for the general population (n = 7), and more than half of the reviews analysed their effect on children (n = 9). The policies/interventions linked marketing strategies with reduction of unhealthy food advertising from different sources (radio, TV, social media), or broadcast marketing policies with unhealthy food intakes or purchases. The policies/interventions analysed were either mandatory or voluntary. Five reviews reported results separately for voluntary and mandatory policies/interventions (Chambers et al., 2015; Galbraith-Emami & Lobstein, 2013; Kovic et al., 2018; Ronit & Jensen, 2014; Taillie et al., 2019; Temme et al., 2020) and all concluded that voluntary marketing restrictions by the food industry are less effective than mandatory government regulations. According to the results, only countries that enacted statutory regulation saw a decrease in sales per capita, while there was an increase in sales of those products in countries with only self-regulatory policy (Kovic et al., 2018). Taillie et al. (2019) reviewed the impact of restrictions on marketing of unhealthy foods and on marketing of all commercial products (including food) and concluded that there is a small or no effect from such strategies, partly because marketing is shifted to other programs or venues (Taillie et al., 2019). Overall, current advertisement bans and statutory regulations seem hard to evaluate, but the evidence suggests that even if bans have little effect in comparison with other policies/interventions, they are estimated to be very cost-effective (Cawley & Wen, 2018). A growing body of literature using laboratory controlled trials shows that advertisements for foods marketing restrictions for unhealthy foods to children impacts food intake, but evidence remains scarce on the differential impact of advertising to children across social groups, as few of these studies consider participants’ demographic differences (Lobstein et al., 2020). None of the reviews analysed the effectiveness of marketing restrictions for breastfeeding substitutes.

5.3.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

When analysing policies/interventions related to food promotion none of the reviews included undernutrition. The majority of the reviews describing the effect on nutrition/healthy diets reported overall positive effects (Lobstein et al., 2020; Russo et al., 2020; Pérez-Ferrer et al., 2019; Kovic et al., 2018; Hillier-Brown et al., 2017; Chambers et al., 2015;), concluding that government regulations were more effective than voluntary pledges. However, some reviews reported neutral effects (Galbraith-Emami & Lobstein, 2013; Ronit & Jensen, 2014; Taillie et al., 2019). The reviews aiming to analyse the effects of marketing restrictions of unhealthy products on obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability and nutrition inequalities did not find sufficient data.

5.3.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

With regard to nutritionally vulnerable populations (i.e., children, Indigenous populations) the results are mixed as some reviews reported overall positive results on nutrition/diets (Chambers et al., 2015; Pérez-Ferrer et al., 2019; Russo et al., 2020), while other reported neutral effects (Galbraith-Emami & Lobstein, 2013; Taillie et al., 2019), or found no evidence of effects of the intervention on their nutritional status or exposure to unhealthy diets/products (Aceves et al., 2020; Browne et al., 2020; Cawley & Wen, 2018; Pérez-Cueto et al., 2012). None of the reviews analysed the impact of food promotion policies/interventions on women’s empowerment.

5.3.2.1 Food promotion: synergies and trade-offs

No synergies or trade-offs were identified.

5.4 Food provision

The policies/interventions analysed included strategies in different food provision locations (i.e., preschools, schools, childcare settings, universities, public setting canteens, healthcare settings and workplaces). The policies/interventions analysed could be categorised overall in two groups, the majority of them providing healthy food provision or reducing the provision of unhealthy foods, while some also used nudging strategies changing the physical food micro-environments to encourage the selection of healthier products or discourage unhealthier ones. The policies/interventions analysed were either mandatory or voluntary.

5.4.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

From the reviews considering undernutrition as an outcome (n = 9), and only a few found sufficient information, of which the majority reported overall positive effects (Cohen et al., 2021; Colley et al., 2019; Holley & Mason, 2019; Menon & Peñalvo, 2019a, b). The vast majority of the reviews (n = 62) described the effect of food provision policies/interventions on nutrition/healthy diets, linking the strategies with positive effects such as reductions of unhealthy foods (mainly SSBs) or increase of healthy food intakes or purchases [mainly fruits and vegetables (F&Vs) and water intake, and in some cases whole grains, milk and fish]. The majority of reviews analysing the effects of the policies/interventions on obesity/NCDs reported overall positive effects (Naicker et al., 2021a, b; Singhal et al., 2021; von Philipsborn et al., 2020; Browne et al., 2020; Carducci et al., 2020; McHugh et al., 2020; Wethington et al., 2020; Adom et al., 2019; Poscia et al., 2018; Bird et al., 2018; Meiklejohn et al., 2016; Avery et al., 2015; Kumanyika et al., 2014; Driessen et al., 2014; M. Niebylski et al., 2014; Sreevatsava et al., 2013; De Bourdeaudhuij et al., 2011), even if the need for more evidence on long-term effects was highlighted (von Philipsborn et al., 2020). The reviews aiming to analyse the impact of policies/interventions on environmental sustainability found overall positive results (Brennan & Browne, 2021; Takacs & Borrion, 2020; Temme et al., 2020). The results from the reviews analysing nutrition-inequalities were mixed, as the majority reported positive effects (Black et al., 2017; Holley & Mason, 2019; Kirkpatrick et al., 2018; Kumanyika et al., 2014), but some of higher quality found negative effects associating the interventions with impacts among higher socio-economic groups (Amini et al., 2015; Thomson et al., 2018). Other reviews found no evidence (Temme et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2018).

5.4.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

Most reviews reported overall positive results linking the policies/interventions to either an improvement on diets or on nutrition parameters of nutritionally vulnerable populations. However, two reviews reported no changes following the intervention (Aldwell et al., 2018; Tseng et al., 2018) while others reported mixed effects (Vargas-Garcia et al., 2017; Hyseni, Atkinson, et al., 2017; Poscia et al., 2018; Thomson et al., 2018). None of the reviews analysed the impact of food provision policies/interventions on women’s empowerment.

5.4.3 Food provision: synergies and trade-offs

Some food provision policies/interventions have shown double-duty potential. For instance, universal free school meals/breakfast programs have positive effects on improving nutrition and/or reducing undernutrition, and nutrition inequalities (Cohen et al., 2021; Colley et al., 2019; Holley & Mason, 2019; Menon & Peñalvo, 2019a, b). In addition, one review suggested potential synergic effects combining provision and retail policies, as interventions in schools combined with regulations in the surrounding stores were effective in improving nutrition and reducing nutritional inequalities (Ewart-Pierce et al., 2016). Some trade-offs were identified, as there may be a link between provision of healthy food and an increase of food waste (Metcalfe et al., 2020). On the other hand, another review reported that healthy food provision programmes that improve dietary quality were associated with food waste reductions (Mansfield & Savaiano, 2017), and another review analysing this same outcome reported positive results in restaurants, but mixed effects in school settings (Brennan & Browne, 2021).

5.5 Food retail

The policies/interventions analysed in the reviews included multiple strategies across diverse locations (i.e., supermarkets/stores, vending machines, food services, university/school surroundings, online shops). The types of policies/interventions analysed were categorised in two main groups. The first and main one was nudging strategies, modifying the context, defaults or norms of consumption by changing the physical food micro-environments to encourage the selection of healthier products, or to discourage unhealthier ones. In addition, included variations in at point-of-purchase on product placement, shelf space, accessibility, distance/proximity, availability, portion, prices (e.g. discounts, monetary incentives…), swaps (changing the shelf disposition or offering consumers the opportunity to replace their usual product for a healthier alternative), and/or promotions in stores or supermarkets. The second group were policies/interventions related to food infrastructure accessibility, such as community-based programmes for farmer’s markets in the neighbourhoods, creation of new food stores and/or improvement of existing ones, supermarket tax or grant incentives to independent grocery stores, or zoning laws (such as bans on new fast-food chain outlets).

5.5.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

The effects on undernutrition were described in one review (Sirasa et al., 2019) which found positive effects related to accessibility/availability of food stores within the surrounding environment. All of the thirty-six reviews (n = 36) described the effect of policies/interventions on nutrition/healthy diets, of which the majority found positive effects in the reduction of unhealthy food or in the increase of healthy food intakes or purchases (mainly for SSBs and F&Vs), particularly for those interventions involving prices or the 4Ps of marketing (influencing the product, price, promotion and/or placement). The reviews analysing the effects of policies/interventions on obesity/NCDs reported overall positive effects (Bird et al., 2018; Gittelsohn et al., 2012; Luongo et al., 2020; S. Roberts et al., 2019; Shaw et al., 2020). No information was available on the impact of policies/interventions environmental sustainability (Temme et al., 2020). The reviews including nutrition inequalities reported mixed results and the overall direction could not be determined (Fergus et al., 2021; Hartmann-Boyce et al., 2018; Temme et al., 2020; Tseng et al., 2018).

5.5.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

The majority of the reviews reported overall positive effects on the nutrition/healthy diets of nutritionally vulnerable populations (i.e., children, Indigenous populations, low-income) (An et al., 2019; Browne et al., 2020; Fergus et al., 2021; Gittelsohn et al., 2012; Luongo et al., 2020; O’Dare Wilson, 2017; Sirasa et al., 2019; Temme et al., 2020). However, some reported mixed results (Løvhaug et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2013; Turner et al., 2019), one neutral effects (Tseng et al., 2018) and other reviews found no evidence of beneficial effects of the interventions on the purchase of healthier items/products (Kumanyika et al., 2014; Sisnowski et al., 2017; von Philipsborn et al., 2020). None of the reviews analysed the impact of food retail policies/interventions on women’s empowerment.

5.5.3 Food retail: synergies and trade-offs

A synergic effect identified the beneficial effect of combining food prices and retail policies/interventions, as the placement of healthier foods together with subsidy programmes may have a positive effect on consumers’ purchases (Gittelsohn et al., 2017). Similarly, one review suggested potential synergic effects when combining provision and retail policies, as interventions in schools with regulations in the surrounding stores were effective in improving nutrition and reducing nutritional inequalities (Ewart-Pierce et al., 2016). No trade-offs were identified.

5.6 Food prices

The food prices policies/interventions analysed included fiscal measures by national, regional or local governments, subdivided in two main categories: (1) taxes and levies (e.g. for fast-foods, TFA, SSBs…) and (2) subsidies [e.g. value-added tax (VAT) reduction/removal for F&Vs, vouchers, food banks, food benefit programmes…].

5.6.1 Primary outcomes: undernutrition, obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability, nutrition inequalities

The reviews analysing the impact of the policies/interventions on undernutrition showed overall positive effects (in particular for subsidies) (Durao et al., 2020; Holley & Mason, 2019; A. J. Moran et al., 2020; Verghese et al., 2019). Most of the reviews (n = 51) described the effect on nutrition/healthy diets, showing an overall positive effect both for taxes and subsidies (Browne et al., 2020; Durao et al., 2020; Hillier-Brown et al., 2017; Lhachimi et al., 2020; Naik et al., 2019; Pfinder et al., 2020; von Philipsborn et al., 2019, 2020; Wolfenden et al., 2021). Those reviews analysing the effects of fiscal measures on obesity/NCDs showed mixed results, as some could find data on purchase changes but not enough on obesity prevalence (Pfinder et al., 2020; Lhachimi et al., 2020; Verghese et al., 2019; Roberts et al., 2017; E. A. Finkelstein et al., 2014). In addition, other reviews reported a positive effect on body mass index (BMI) reduction but no data on obesity prevalence or diet-related NCDs (Afshin et al., 2017; Park & Yu, 2019). The reviews describing the impact of fiscal measures on environmental sustainability did not find sufficient data (Haby et al., 2016; Temme et al., 2020), whereas those analysing nutrition inequalities were numerous (n = 16) and showed overall positive effects (Kirkpatrick et al., 2018; Løvhaug et al., 2022; Naik et al., 2019; Powell et al., 2013; Temme et al., 2020). However, one review concluded that taxes on SSBs were more effective among lower socio-economic groups (Lobstein et al., 2020).

5.6.2 Secondary outcomes: nutritional vulnerabilities and women’s empowerment

The effects of fiscal measures were overall positive among nutritionally vulnerable populations (i.e., children, women, Indigenous populations, low-income groups) (An, 2013; Browne et al., 2020; Durao et al., 2020; Holley & Mason, 2019; Schultz et al., 2015; Sisnowski et al., 2017; Thomson et al., 2018; Verghese et al., 2019; Wolfenden et al., 2021). However, some reviews reported mixed results (Dangour et al., 2013; Pullar et al., 2018; von Philipsborn et al., 2020), and one found no evidence of beneficial effects of the intervention (V. H. Moran et al., 2015). None of the reviews analysed the impact of fiscal measures on women’s empowerment.

5.6.3 Food prices: synergies and trade-offs

The results of the reviews suggest that fiscal measures can have double-duty potential, as they may reduce nutrition inequalities while improving population’s nutrition. Moreover, subsidies have shown to contribute to the double burden of malnutrition, being effective both for undernutrition and healthy dietary intakes (Durao et al., 2020; Verghese et al., 2019). A synergic effect identified is the beneficial effect of combining fiscal measures with retail policies/interventions, as the placement of healthier foods in combination with subsidy programmes may have a positive effect on consumers’ purchases (Gittelsohn et al., 2017). A potential trade-offs may be the unintended compensatory purchasing resulting from subsidies, which may lead to additional unhealthy food purchase with the money saved (Dangour et al., 2013; Dodd et al., 2020).

5.7 Summary per (sub)domain: multi-component policies and interventions

The so-defined group of “multi-component” included those reviews that analysed the impact of policies/interventions when implemented in combination with others considered to have a potential synergic effects. Twenty-five reviews on multi-component policies/interventions did not use methods that allowed for separate analyses of outcomes per intervention component, so they were classified according to the (sub)domains included in the multi-component policies/interventions and described more into detail in the Supplementary File 6. However, 10 reviews allowed for a separate analysis of each included intervention, and their effect on the outcomes were described under the corresponding (sub)domain paragraph, and their overall direction is included in Table 4.

Four reviews analysed the impact of interventions combining reformulation with labelling. Those reviews reported effects on nutrition, but the results were mixed. Those that also focused on the impact on obesity/NCDs suggested a positive effect on NCDs (Musicus et al., 2020) or did not find enough data (Hyseni, Bromley, et al., 2017). Another review reported a positive impact on nutrition inequalities, suggesting that the multi-component intervention was pro-equity (Hendry et al., 2015). However, a review summarising the effect of combining food labelling and composition, together with education campaigns (a type of intervention not included in this scoping review – see Table 3), reporting an overall neutral effect on nutrition inequalities (Thomson et al., 2018). In this same line, another study concluded that multi-component interventions combining labelling, reformulation, healthy food provision and promotion or reformulation, labelling and promotion had positive effects on nutrition/healthy diets (Hyseni, Atkinson, et al., 2017). A similar study reported a positive effect both on nutrition/healthy diets and in obesity/NCDs indicators when combining food reformulation, labelling, healthy food provision and taxes on foods high in sodium (Hyseni, Elliot-Green, et al., 2017).

Another set of three reviews analysed the impact of policies/interventions combining food provision and food retail in children (Bramante et al., 2019; Pineda et al., 2021) and in the general population (Ewart-Pierce et al., 2016), showing positive effects on obesity/NCDs and both for gender and socio-economic groups, and overall mixed effects for nutrition/healthy diets. Other reviews summarized the impact of multi-component interventions combining reformulation, marketing, labelling, healthy food provision, in-stores nudging strategies or fiscal measures, reporting overall positive effects and suggesting that taxes and subsidies in combination with nudging strategies may incentivise the purchase of healthier foods and the reduction of unhealthier ones (Hillier-Brown et al., 2017; Russo et al., 2020).

The reviews summarising the effects of combining food production (garden-based strategies) and food provision (increasing the availability and provision of healthier options), suggested an overall positive impact both for nutrition and obesity/NCDs indicators in children (Bleich et al., 2013; Chaudhary et al., 2020). Other reviews described the impact of combining labelling and food provision policies/interventions in nutrition/healthy diets among school-aged children, one reporting mixed results (Nørnberg et al., 2016), whereas the other suggested an overall positive effect (Wang & Stewart, 2013). Similarly, reviews focusing on the impact of combining food labelling-provision-retail strategies showed a positive effect on nutrition/healthy diets (Naicker et al., 2021a; Roy et al., 2015). However, when analysing the impact on obesity/NCDs, one did not find enough information to reach a conclusion (Naicker et al., 2021a), whereas the other study suggested an overall positive effect on BMI and overweight prevalence (Roy et al., 2015).

When it comes to synergies related to multi-component interventions involving prices, Noy et al. (2019) reported positive effects both for undernutrition and nutrition when combining garden interventions with tax incentives to increase access to food (Noy et al., 2019). An overall positive effect on nutrition/healthy diets was found both for subsidies alone or in combination with increased availability of healthy foods in school environments (Jensen et al., 2011). Another review reported positive effects on nutrition/healthy diets for prices alone or in combination with food labelling and/or nudging interventions in the physical environment of retail shops. However, the results did not find any consistent effects on BMI changes of the population studied (Gittelsohn et al., 2017).

6 Discussion

6.1 Summary of main findings

This scoping review found substantial evidence of the effectiveness of food system policies/interventions in improving population nutrition and environmental sustainability, and addressing nutrition-related inequalities.

Overall, the majority of the evidence included in the review reported a positive effect on the outcomes studied. Within the domain of food supply chains, the interventions related to food production (such as agroecology, crop diversification, bio-fortification or school gardens) and those on food processing (such as fortification) showed positive results tackling undernutrition and food insecurity, across different population groups. Similarly, for the domain of food environments the evidence available showed positive effects of food provision policies/interventions (universal free school meals and breakfast programmes), food retail (accessibility/availability of stores within the surrounding environment) and food prices (subsidies for F&Vs, vouchers, food banks, food benefit programmes) in tackling undernutrition and food insecurity.

The effects of policies/interventions on healthy diets/nutrition have been synthesized for all the (sub)domains reviewed (with the only exception of food loss and waste) and showing mostly positive effects. For the particular case of food labelling, the overall direction of results shows the positive impact of labels reducing population’s dietary intake of selected nutrients, while it tends to influence industry food reformulation practices. However, despite the evidence available, the effectiveness of labels toward healthier or more environmentally sustainable food purchases remains mixed and inconclusive (An et al., 2021; Anastasiou et al., 2019; Temme et al., 2020; Moran et al., 2020; Hyseni, Atkinson, et al., 2017). The inconclusiveness of results may be explained by the diversity of food labelling policies, as they include different types of FOPNL graphic designs or types of menu labelling.

For the outcome of obesity/diet-related NCDs, evidence available on the effectiveness of interventions remains scarce as, even if some reviews analysed the impact of policies on BMI, their long-term effect on obesity prevalence and diet-related NCDs has not been demonstrated by many studies. The limited evidence available suggests positive effects from all the policies/interventions implemented within the domain of food environments, and for food production.

Just 21 reviews aimed at evaluating the effectiveness of policies/interventions on environmental sustainability, of which six did not find consistent results, so overall fewer information was gathered for this outcome. Food production policies/interventions (such as crop and livestock diversification strategies, agroecology practices, provision of agricultural technology) showed positive effects on soil erosion, biodiversity loss and water use (El Chami et al., 2020; Feliciano, 2019; McElwee et al., 2020; Nasir Ahmad et al., 2020). For the (sub)domain of food provision, two reviews (Brennan & Browne, 2021; Takacs & Borrion, 2020) found positive effects of food waste/portion reduction strategies in different settings (such as schools, restaurants, workplaces).

In the particular case of women’s empowerment, however, no information could be found for the majority of the (sub)domains, with the exception of food production and food trade and investment agreements. The question that may arise from this result is whether the information was not found due to a lack of research in the area and requires further studies, or because it lacks of applicability, the latter meaning that some (sub)domain may do not have a link to women’s empowerment. This lack of evidence may also be because women’s empowerment is a variable very difficult to measure. In addition, in this scoping review, women’s empowerment was considered as an outcome but in some studies the framework may have been different and it was considered as the driver to achieve an action.

6.2 Research implications

Current evidence remains highly heterogeneous across types of policies/interventions, making it often incomplete when it comes to the food system perspective. The scientific evidence available until the date tends to analyse the impact of different agriculture, health or food policies for a single outcome. In addition, there are remaining gaps in the literature. There is a number of food system policies/interventions whose effect on undernutrition, obesity and/or climate change has not been properly evaluated in systematic reviews. One example is the (sub)domain of food loss and waste, which remains underexplored despite its strong link with undernutrition and environmental sustainability (C. Chen et al., 2020). Other understudied (sub)domains are (1) food storage, processing, packaging and distribution (as the majority of the reviews were on the food processing aspect and consisted on fortification interventions), and (2) food trade and investment agreements.

For other (sub)domains, such as food composition, the evidence available is still limited, and to date only its link with nutrition/healthy diets has been assessed. However, strong government leadership and its mandatory implementation seem to be critical success factors (Jones et al., 2016; Kleis et al., 2020). Similarly, for food promotion (marketing), despite the limited evidence available, policies/interventions banning or limiting the exposure to unhealthy food products show a slight positive impact on improving diets. This weak evidence may be due to lack of adherence from the industry, from a lack of resources available to proper monitoring and enforcement (Aceves et al., 2020), or because the policies may not be comprehensive/extensive enough when mandatory, as marketing is then shifted to other programs or venues (Taillie et al., 2019). However, data available in reviews was scarce, and some recent evidence suggests that food marketing policies may result in reduced purchases of unhealthy foods (Boyland et al., 2022).

The evidence available for other aspects analysed in this scoping review is still very limited, such as the effects that agriculture and food policies/interventions have on different indicators of environmental sustainability, on gender equality and on women’s empowerment. Nevertheless, the evidence available per outcome depends on each domain or even (sub)domain. For instance, the outcomes of obesity/NCDs, environmental sustainability and nutrition-related inequalities have been understudied within the domain of food supply chains, and in the reviews where they were included, the evidence available was not strong enough to be significant. However, within the domain of food environments, the outcomes that were understudied were undernutrition, environmental sustainability and nutrition-related inequalities. In addition, enough reviews across domains reported results in nutritionally vulnerable populations, but it was not the same for women’s empowerment.

In the case of obesity/NCDs, evidence may be scarce because research in this area is still recent and there is a lack of information available for the long-term impact of policies/interventions implemented. In the case of environmental sustainability, evidence is only available for food production strategies, and overall scarce due to lack of reviews analysing the effectiveness of sustainable agriculture policies/interventions. These results are in line with previous research in this area (Haby et al., 2016), which highlights that agricultural practices are rarely studied in the area of food policy, despite its link with environmental sustainability. The impact of policies/interventions on socio-economic inequalities is generally not reported, with the exception of the reviews on taxes and subsidies. Therefore, the effects for other (sub)domains is still uncertain. Even if more research specific on the impact of nutrition-related inequalities is needed, some recent reviews on food composition and food labelling have started to provide the results divided by gender and socio-economic status, which allow to determine the overall direction of the effect.

6.3 Policy implications

Prior, during and after the Food Systems Summit in 2021, a global call for more and better-quality research on policy solutions towards SFS has taken place. Acting on flawed or incomplete information can have costs if the policies implemented are not evaluated properly, or if their repercussions and trade-offs have not been properly considered. However, delaying the policies/interventions while waiting for more and better-quality research in all these areas has also a big cost, not only for the research it would require, but more importantly for the cost of not acting. We, therefore, argue for governments to implement policies with proven double- or triple-duty potential, as they have shown their effectiveness tackling malnutrition in all its forms and/or climate change. In this day and age, a careful implementation of policies/interventions likely to make a positive impact combined with thorough monitoring and evaluation is urgent.

For instance, in the domain of food supply chains, an important lesson learnt is the high potential that agricultural policies/interventions have not only to tackle food insecurity but far beyond, given its double-duty potential. Agroecology is a sustainable approach that has been applied for decades in family farmers’ practices around the globe, combining traditional knowledge with scientific evidence, and has shown benefits helping farmers diversify their production, having positive impacts on the diets of the local communities while also strengthening women’s empowerment (Walls et al., 2018). In this line, recent evidence shows its positive effects on gender equality (Benítez et al., 2020), as they increase the inclusion of women developing and implementing in-farm innovations, help strengthen the self-confidence for female farmers and farm-family members, ameliorate productive diversification on family farms and increase employment and household income through women-led micro-industry projects that facilitate of commercialization opportunities. Even if the evidence included in this scoping review is still limited, some studies on agricultural practices have also shown positive links with obesity prevention through healthier diets (Deaconu et al., 2021), suggesting its triple-duty potential.

Another action that has shown to be promising in many countries and regions worldwide is related to food provision in schools. Nutrition programmes have a positive effect on healthy diets, also improving the BMI of children in the long term. These programmes are also powerful tools to reduce micronutrient deficiencies (Colley et al., 2019), food insecurity (Cohen et al., 2021) and nutrition inequalities (Løvhaug et al., 2022), and have shown favourable economic benefits (Ekwaru et al., 2021). These benefits, that go in line with similar research in the field (Venegas Hargous et al., 2023), should not be underestimated by governments. However, some strategies that increase the acceptability of healthier food groups (such as F&Vs), have been suggested to increase the amount of food wasted (Metcalfe et al., 2020; Prescott et al., 2020). This could be prevented by re-designing programmes that minimise food waste, such as awareness and education campaigns, which have proven to be effective (Soma et al., 2020). Overall, due to its positive effects in reducing micronutrient deficiencies and overweight, food provision policies/interventions may have double-duty potential, and may be beneficial for reducing nutrition-related inequalities. However, more research is needed to fully understand their effects on environmental sustainability.

When it comes to food price policies/interventions, the evidence shows that food subsidies and social programmes have a relative large impact on food purchases and healthier diets (Wolfenden et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2020). In the countries or regions in which taxes on SBBs have been implemented, such as Mexico (Aceves et al., 2020), South Africa (Hofman et al., 2021), or the United Kingdom (Pell et al., 2021), taxes have shown a positive impact on the transition towards healthier habits, showing significant drops on their purchases. Interestingly, a recent study suggests that taxes may incentivise food reformulation across manufacturers (Scarborough et al., 2020), a similar phenomenon to the one results from food labelling. In addition, going beyond sugary drinks, taxes implemented in red and processed meat products may have double-duty potential (improving health and environmental sustainability), as suggested by some studies (Broeks et al., 2020; Springmann et al., 2018; Wirsenius et al., 2011). Even if none of the reviews included described food pricing strategies on red or processed meats.

Information-type interventions, such as food labelling and food retail, have shown to be effective of in improving nutrition/healthy diets. Recent evidence shows positive results on healthier choices or purchases made by consumers in different parts of the world and settings in particular for menu labelling in quick-service restaurants. This type of intervention could have double-duty potential, as environmental sustainability labels have been associated with the selection and purchase of more sustainable food products (Potter et al., 2021) representing a key area to explore further. Moreover, an additional synergy for food labelling is its impact on food composition, as industry and retail services tend to use reformulation as to improve the labelling of products or menus (Russo et al., 2020; Shangguan et al., 2019). However, when it comes to nutrition-related inequalities, there is evidence that certain types of labels may be more effective among women and among higher-income and education groups. This aspect should be taken into account to prevent inequalities, ensuring that food labels are easily understood by all [for instance by prioritising the use of colour-coded traffic-light instead of numerical format, as suggested by Lobstein et al. (2020) and Cecchini and Warin (2016)]. Also, when designing policies/interventions in these areas, monitoring programmes should be in place to quantify possible negative or unintended effects, and implement solutions.

Current trade and investment agreements need urgent revision due to their negative effects on various outcomes, as these policies were not designed taking into consideration the healthiness of populations diets or environmental sustainability, but rather to satisfy the global demand for products and ensure food security. As this requires action at global scale, with the results of this scoping review we urge policymakers to implement nutrition, health and environmental impact assessments when designing food trade policies and international agreements.

It is important to highlight that the overall results from this scoping review should be seen as an overall summary of evidence-based effects of food systems policies, but should be contextualised and adapted to each context and situation. The effects and effectiveness of certain policies/interventions may vary based on the specific geographic region, on the setting (urban, peri-urban or rural), or many other environmental, economic, social and cultural factors that were not analysed in detail in this review, given its broad scope.