Abstract

Multilevel modelling has become a popular analytical approach for many demographic and health outcomes. The objective of this paper is to systematically review studies which used multilevel modelling in demographic research in Africa in terms of the outcomes analysed, common findings, theoretical rationale, questions addressed, methodological approaches, study design and data sources. The review was conducted by searching electronic databases such as Ebsco hosts, Science Direct, ProQuest, Scopus, PubMed and Google scholar for articles published between 2010 and 2021. Search terms such as neighbourhood, social, ecological and environmental context were used. The systematic review consisted of 35 articles, with 34 being peer-reviewed journal articles and 1 technical report. Based on the systematic review community-level factors are important in explaining various demographic outcomes. The community-level factors such as distance to the health facility, geographical region, place of residence, high illiteracy rates and the availability of maternal antenatal care services influenced several child health outcomes. The interpretation of results in the reviewed studies mainly focused on fixed effects rather than random effects. It is observed that data on cultural practices, values and beliefs, are needed to enrich the robust evidence generated from multilevel models.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The term multilevel or hierarchical modelling has been used in various fields such as demography, education and sociology to describe an approach that allows the simultaneous examination of the effects of group and individual-level factors on individual-level outcomes (Diez-Roux, 2000). It also refers to an approach used to analyse clustered or grouped data in which the units at one level are grouped at a higher level (Kreft et al., 1998; Parr, 1999). It involves an analysis of data collected at multiple levels of aggregation such as data from surveys that collect data on children, their mothers and the communities they reside in (Courgeau, 2007). Multilevel modelling considers aggregate characteristics as external factors that affect individual behaviour and incorporates the context into the individual-level models (Courgeau, 2007). The use of multi-level modelling assists in analysing the micro–macro relationships between individuals and their context simultaneously (Duncan et al., 1998; Zaccarin & Rivellini, 2002).

Multilevel modelling answers research questions that seek to understand how outcomes at the individual level can be a result of the interplay between individual and contextual factors. It is vital in investigating a variety of interrelated research questions such as assessing whether groups differ after controlling for the characteristics of individuals within them, and examining if the group-level variables are related to outcomes after controlling for individual-level variables (Diez-Roux, 2000). It allows the separation of the effects of context (group characteristics) and composition variables (Diez-Roux, 2000). The comparisons of group-level variance before and after the inclusion of individual-level characteristics enable the identification of the extent to which between-group variability is linked to compositional effects (Chaix & Chauvin, 2002).

Multilevel modelling is widely used in demographic research and other social science disciplines. In Demography, studies have used multilevel modelling to examine the determinants of child mortality, childhood immunization, children’s nutritional status, health care utilization, reproductive health matters and family dissolution. This is because demographic processes are not only affected by individuals but by the characteristics of the environments, they live in (Odimegwu et al., 2017a).

The purpose of this systematic review is to profile the use of multilevel modelling in demographic research in Africa in terms of the outcomes analysed, common findings, theoretical rationales, questions addressed, methodological approaches, study designs and data sources. The systematic review is important in that it sheds light on how the micro–macro continuum has been analysed in explaining various demographic outcomes in sub-Saharan Africa. We also discuss the limitations and policy implications raised by the studies. As far as we know, this is the first systematic review of Multilevel Modelling in Demographic Research in Africa.

Methods

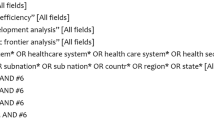

The systematic literature review was conducted by searching electronic databases such as Ebsco hosts, Science Direct, ProQuest, Scopus, PubMed and Google scholar for articles that were published between 2010 and 2021. This was done to obtain recent studies. A database search was conducted between May 2019 and February 2021. The search terms used included neighbourhood, contextual, community level, composition, individual characteristics, multilevel modelling, demographic and health survey and Africa. This involved using Boolean operators; AND, OR during database searching. The use of the search terms together with the Boolean operator provided us with articles which used the multilevel modelling method. The search also involved citation snowballing during which the reference list of identified articles was checked for additional relevant papers. This led to 329 papers being identified, from these papers those older than 10 years were excluded leading to 174 articles. After removing studies that were not conducted in Africa, 92 remained and 47 articles that were not from the field of demography were removed. The articles included a focus on understanding population dynamics through demographic processes such as mortality, fertility, and migration as they contribute to changes in population (Rowland, 2003). Research articles which investigated population health issues but were qualitative were removed since demography is the quantitative study of population processes. Papers which had the measures of variation displayed in the results tables but not interpreted were included in the study resulting in 35 papers being reviewed. In all the mentioned stages, the inclusion criterion was based on the premise that the study should have used community-level factors to examine a selected demographic outcome. Studies that comprised any demographic outcome and did not use any community-level factors were excluded from the systematic review (Fig. 1).

Findings

In total, 35 quantitative articles were reviewed with 34 being peer-reviewed journal articles and 1 technical report (Ejembi et al., 2015). All of the articles used a cross-sectional design and 30 of the articles used Demographic and Health Survey Data. Two of the articles used surveys such as the Tanzania HIV and Malaria indicator survey (Adinan et al., 2017) and the other used the Uganda AIDS indicator survey ((Igulot & Magadi, 2018). The reviewed studies have been conducted in different parts of Africa and present similar findings regarding the association between community-level factors and different demographic outcomes. The papers in which the community-level variables were statistically significant were summarised using the significant community variables to create themes. The themes were based on a specific community-level factor’s association with various demographic outcomes. The measures of variation such as the Intra-class Correlation Coefficient (ICC) and Proportional Change in Variance (PCV) of the reviewed studies were presented in Table 1 in the appendix. The measures of variation in Table 1 show that both individual and community-level factors explained the variance between communities of the different demographic outcomes. For instance, a study that assessed individual and community-level factors associated with childhood full immunization in Ethiopia, indicated an ICC of 25.39% showing that the variance in the odds of childhood full immunization between communities was explained by individual-level characteristics only (Abadura et al., 2015). The PCV was 21% indicating that the variance in the odds of childhood full immunization between communities was explained by individual-level factors. In the model which had community-level variables only, the ICC of 19.95% indicated that the variation in childhood full immunization was due to community-level characteristics. A PCV of 42% in the likelihood of full immunization across communities was explained by community-level factors. Meanwhile, an ICC of 20.53% of the variance in the odds of full immunization across communities was due to the simultaneous effects of both individual and community-level factors. A PCV of 40% indicated that the odds of full immunization across communities were explained by both individual and community-level factors (Abadura et al., 2015). The individual-level factors which were statistically significant were not included in the findings section since the main aim of the paper was to discuss contextual factors related to various demographic outcomes.

To illustrate the relevance of multilevel modelling, the studies focused on various demographic outcomes such as childhood immunization (Abadura et al., 2015; Adedokun et al., 2017a; Wiysonge et al., 2012), child wasting and underweight (Akombi et al. 2017), low birth weight (Kayode et al., 2014), childhood stunting (Adekanmbi et al., 2013), under-five mortality (Adedini et al., 2015; Adedini & Odimegwu 2017; Antai, 2011), acute respiratory infections (Adesanya & Chiao, 2016) and health care service utilization (Adedokun et al., 2017a, 2017b; Adinan et al., 2017). The other indicators include adolescent mortality (De Wet & Odimegwu, 2017), modern contraceptives use (Akinyemi et al. 2017a, 2017b; Ejembi et al., 2015; Ngome and Odimegwu, 2014), postnatal checkups (Solanke et al., 2017), use of health care facilities for delivery (Ononokpono & Odimegwu, 2014; Yebyo et al., 2014), intimate partner violence (Oyediran & Feyisetan, 2017), as well as family dissolution (Odimegwu et al., 2017a). The findings presented below indicated how various contextual variables were associated with different demographic outcomes.

Community poverty

Poverty is prevalent in most communities within the Sub-Saharan African region. Poverty affects social behaviour and influences most health outcomes with the poor struggling to have access to vital resources. In the reviewed studies, household wealth index variables such as asset scores of the households were used as proxies for poverty. Community poverty was defined as the proportion of women from poor and poorest households or wealth quintiles. Adolescent girls from the rich wealth quintile had an increased likelihood of unintended pregnancy than those in the poor wealth quintile (Ahinkorah, 2020). Adolescents who lived in communities with a medium or high proportion of poverty were at a reduced risk of adolescent mortality than adolescents in communities with low poverty (De Wet & Odimegwu, 2017). Community poverty also influenced the utilization of maternal health care services with most women in communities characterized by higher levels of poverty giving birth at home (Yebyo et al., 2014) and most of them having a lower likelihood of not using postnatal care (Dankwah et al., 2021) and antenatal care (Ononokpono et al., 2013). From these findings, it is clear that community-level poverty matters rather than focusing on the individual level. Women in poorer communities encounter challenges linked to a lack of affordability in terms of transport costs and fees which are sometimes required at health facilities and these are among the reasons which make women not use maternal healthcare services (Dankwah et al., 2021).

The health implications of poverty are shown in the region when children living in communities that have higher levels of poverty had an increased likelihood of dying (Adedini et al., 2015; Zewdie & Adjiwanou, 2017). Also, children living in poorer neighbourhoods had increased reports of missed opportunities for vaccination (Uthman et al., 2018). Meanwhile, women who resided in wealthier communities were less likely to have low birth weight infants compared to those residing in poverty-stricken neighbourhoods (Kayode et al., 2014).

Region and place of residence

Region and place of residence influence the immunization of children in Sub-Saharan Africa. In Nigeria, when mothers move to other states or communities which have a higher probability of incomplete child immunization it also increased their likelihood of not having their children immunized (Adedokun et al., 2017b). Women who faced transport challenges to health facilities were less likely to get their children immunized. Where the distance to the hospital was perceived as a barrier, it resulted in the women not having their children fully immunized (Adedokun et al., 2017b; Ekouevi et al., 2018) and increased the likelihood of women giving birth at home compared to women not living in communities where the distance to the health facility was perceived not to be a barrier (Yebyo et al., 2014). This explains why children from urban areas were more likely to be immunized than those from rural areas (Wiysonge et al., 2012). The immunization of children increased in communities where maternal health care services were prevalent. For instance, in Ethiopia, the presence of maternal care services in a community was associated with an increased likelihood of full immunization of the children (Abadura et al., 2015). Similarly, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, communities with high utilization of institutional service delivery have a greater likelihood of the children being immunized (Acharya et al., 2018).

Maternal healthcare utilization and child health outcomes are also influenced by the region and place of residence. For example, residing in the South West region of Nigeria increased the odds of antenatal care attendance compared to the Northern Central region (Ononokpono et al., 2013). In Ethiopia, women residing in pastoralist and agrarian communities were more likely to give birth at home due to the long distances to health facilities than women residing in cities (Yebyo et al., 2014). In Sierra Leone, Cote d’Ivoire, Guinea, Niger and Liberia all women in rural areas were less likely to use postnatal check-ups compared to their counterparts in urban areas (Solanke et al., 2017). Both region and place of residence determine the child's health outcomes. For instance, residing in a particular region contributed to the underweight of children. In the North-Eastern region of Nigeria, the children who resided in rural areas were more undernourished than those in urban areas (Adekanmbi et al., 2013). Also, children residing in the North West region in Nigeria had an increased likelihood of having acute respiratory infection (ARI) symptoms (Adesanya & Chiao, 2016). Children of mothers residing in rural areas were at an increased risk of under-five mortality compared to those in urban areas (Adedini & Odimegwu, 2017).

Not only does region and place of residence influence the health-seeking behaviours of mothers but also impact their reproductive health. Women residing in rural areas have higher fertility compared to those in urban areas (Odimegwu & Chemhaka, 2021). Women residing in urban areas have a higher likelihood of using modern contraceptives than those in rural areas (Zegeye et al. 2021). This could be linked to the short distance that women in urban areas travel to seek sexual reproductive health services compared to their counterparts in rural areas (Zegeye et al. 2021). Also, some behaviours are linked to the context in which individuals reside.

Community beliefs and myths

In most countries in Sub-Saharan Africa, there are beliefs that one should have more children, especially boys to carry the family name (Fuse, 2010; Olanrewaju et al., 2015; Rossi & Rouanet, 2015). Such beliefs have an impact on the use of contraceptives. For instance, Nigerian women who live in communities where a higher proportion of women believe that the ideal number of children should not exceed four had higher odds of using contraceptives (Akinyemi et al., 2017b). A study conducted in Zimbabwe indicated that residing in communities with a higher mean number of children ever born per woman reduced modern contraceptive use among adolescent women (Ngome & Odimegwu, 2014). In Eswatini, women living in communities with high fertility norms whose ideal number of children was four had a significantly lower likelihood of using contraceptives (Odimegwu & Chemhaka, 2021). However, after controlling for individual factors, the contextual factors were insignificantly associated with contraceptive use. This shows that contextual factors may have important implications for contraceptive use (Odimegwu & Chemhaka, 2021). The beliefs and myths in communities play a vital role in influencing reproductive health outcomes in different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa. In efforts to keep up with the beliefs and myths of the communities, women engage in behaviours that are in line with community beliefs.

Community education

Education empowers women, improving their ability to participate in decision-making. The reviewed studies have used community education and literacy level to refer to the level of education. Education is linked to child health outcomes. Residing in communities with a low proportion of mothers that received prenatal care from a doctor was associated with an increased risk of under-five deaths (Antai, 2011). Education seem to be important in the reduction of under-five mortality. A study conducted in four Sub-Saharan African countries showed that children in communities with a high proportion of educated women were associated with lower under-five mortality risk (Adedini & Odimegwu, 2017). A study in 24 sub-Saharan countries indicated that communities with high illiteracy rates had higher reports of unimmunized children (Wiysonge et al., 2012) and childhood stunting (Adekanmbi et al., 2013). Maternal health care utilization and reproductive health outcomes are also linked to education. Increased community-level education can transcend to a better understanding of the importance of maternal health care services. Communities with higher levels of educated women are more likely to have increased maternal healthcare service utilization. For instance, in Nigeria, females from communities with a high proportion of secondary or higher education had a greater likelihood of delivering a baby in a health facility (Ononokpono & Odimegwu, 2014). Similarly, in Ethiopia, communities with educated females had increased odds of institutional delivery (Mekonnen et al., 2015). The mothers in communities with a higher proportion of secondary education were more likely of using postnatal check-ups compared to mothers from communities with a low proportion of secondary education (Solanke et al., 2017). However, in Tanzania, community education did not influence the utilization of postnatal care (Mohan et al. 2015). Also, the education of mothers protects the health of their children. A study in South Africa showed that in municipalities where the proportion of educated women was high or medium, the likelihood of infants dying was reduced compared to municipalities with a low proportion of educated women (Zewdie & Adjiwanou, 2017). Communities with a high proportion of educated women have an increased likelihood of modern contraceptive use compared to those with a low proportion of educated women (Ononokpono et al. 2020; Ejembi et al., 2015). Not only did education determine the health outcomes, but it also served as a protective factor against family dissolution (Odimegwu et al., 2017a). Community education and family dissolution have been limitedly studied as indicated by the reviewed studies.

Community-level decision-making and employment

Out of the 35 reviewed studies, only one study examined the association between community-level decision-making involvement and childhood mortality. Community-level decision-making involvement was associated with a lower risk of child death (Akinyemi et al., 2017a). In communities where women had higher decision-making in family planning, they were increased use of family planning than in communities where the decision-making was low (Alemayehu et al., 2020). Communities with high female autonomy had increased odds of modern contraceptive use compared to communities with low female autonomy (Ejembi et al., 2015).

Community mass media and access to safe water

The findings further show that the community’s access to mass media was associated with increased odds of antenatal service utilization (Ononokpono et al., 2013). A study conducted in Eswatini indicated at the bivariate level that women living in communities with lower levels of media exposure had reduced rates of contraceptive use (Odimegwu & Chemhaka, 2021). In Ethiopia, communities with higher electronic media possession had an increased likelihood of family planning use compared to communities with lower reports of electronic media possession (Alemayehu et al., 2020). Residing in communities with low coverage of safe water was associated with an increased likelihood of having infants with a low birth weight compared to those living in communities with safe water coverage (Kayode et al., 2014). In Ethiopia, children in communities which lacked an improved water supply were more likely to have diarrhoea compared to children from communities with improved water (Azage et al., 2016).

Community justification for wife-beating

Gender-based violence is not only an individual-level issue but is entrenched within the community’s socio-cultural norms which condone violence against women. For instance, residing in a community with a justification of wife-beating below the median had a reduced likelihood of women experiencing intimate partner violence compared to residing in a community with a justification of wife-beating at the median for the community. In Nigeria, women in communities which accepted that the husband has the right to beat his spouse and those who believed that women have sexual rights had higher odds of experiencing intimate partner violence (Oyediran & Feyisetan, 2017). Despite gender-based violence being condoned, it has negative health consequences for victims, particularly women and children.

Community polygyny

Community polygyny plays a crucial role in determining child health outcomes and sexual reproductive health in most sub-Saharan countries. In Nigeria, communities with a higher proportion of polygynous marriages had a reduced likelihood of using modern contraceptives than communities with a lower proportion of polygynous marriages (Ejembi et al., 2015). Studies have shown that living in communities with higher levels of polygamous relationships is associated with a greater likelihood of being infected with HIV than living in communities with no polygamous relationships (Igulot & Magadi, 2018). In Sub-Saharan African countries where polygyny is common, it is associated with multiple sexual partners (Uchudi et al. 2012). A study conducted in 29 sub-Saharan African countries highlighted that the risk of infant mortality was higher in regions with a contextual prevalence of polygyny (Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, 2014). The latter study further added cross-level interaction terms which indicated a positive cross-level interaction between contextual (region-level) prevalence of polygyny and family-level structure and showed that the infants’ survival disadvantage associated with polygyny increases in settings where the practice is widespread compared with monogamy (Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, 2014). For instance, infants from polygynous families living in regions where polygynous is rarely practised have a lower likelihood of experiencing infant mortality while infants from polygynous families but residing in contexts with an increased prevalence of polygynous union have a higher likelihood of experiencing infant mortality compared to infants in monogamous families (Smith-Greenaway & Trinitapoli, 2014).

Community attitudes, condom use and early marriage

Surprisingly, living in communities where women would know that their husbands had STIs and asked them to use condoms increased the prevalence of HIV in the community (Igulot & Magadi, 2018). Interestingly, the use of condoms was associated with an increased likelihood of being infected with HIV (Igulot & Magadi, 2018). Meanwhile, living in communities in which cash work is prevalent with individuals desiring to advance themselves influences unmarried women’s likelihood to have multiple sexual partners (Uchudi et al., 2012). Multiple sexual partners were also common among individuals who initiated sexual intercourse at an earlier age (Uchudi et al., 2012). Having multiple sexual partners and engaging in early marriages influenced the prevalence of HIV. For instance, in Uganda, an increase in people who marry or cohabit before the age of 20 years old increases the prevalence of HIV in the community (Igulot & Magadi, 2018). This shows that attitudes and behaviours within the community are vital in explaining health outcomes among individuals. The existing social structure within the communities compels individuals to act in a way that exposes them to HIV. The practices of early marriage leave young women without choices when engaging in sexual activities.

Methodological approaches

Most of the studies applied a two-level multivariate regression analysis; the first level indicated the relationship between the individual-level variables and the outcome variable. The second level examined the influence of community-level factors on the outcome variable. Only three studies used a three-level model, for instance, a study on infant mortality had at the first level children born 12 months before the census, the second level was municipalities, and the third level was provinces in which the children lived (Zewdie & Adjiwanou, 2017). A study which focused on factors associated with missed opportunities for vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa had children aged between 12 and 23 months in level one, neighbourhoods in level two and countries the children lived in were in level three (Uthman et al., 2018). Another study had children who were fully immunized or not (level 1), nested within 896 communities (level 2) from 37 states (level 3) in Nigeria (Adedokun et al., 2017a). Almost all the studies had a null model to check for variability among the communities to justify that the data can be used to assess the random effects at the community level (Adedokun et al., 2017a, 2017b; Adekanmbi et al., 2013; Akinyemi et al., 2017a, 2017b; Antai, 2011; De Wet & Odimegwu, 2017). In some studies, the null model was used to decompose the variance between the community and state-level factors (Adedokun et al., 2017a, 2017b).

The studies used the Intra-cluster correlation coefficient (ICC) as a measure of variation (random effects) and check the clustering of the outcome variables within the communities (Abadura et al., 2015; Adinan et al., 2017; Azage et al., 2016; De Wet & Odimegwu, 2017). The ICC and PCV of the reviewed papers are shown in Table 1 in the appendix. Reviewed papers without a PCV in the appendix show that it was not included by the authors. The paper reviewed the significance of the community-level factors in the full model after controlling for both individual and community-level factors. The corresponding variances of the random effects are indicated in the appendix. Out of the reviewed studies, only three investigated cross-level interactions between individual and community factors (Adedini & Odimegwu, 2017; Abadura et al., 2015).

Importance of Multilevel (two-level) models over single-level models

Multilevel modelling is important because hierarchical or nested data structures are not independent therefore data analysis techniques for single-level data cannot be used since the assumption of independence is violated. In nested data, observations are not independent because individuals from the same community may be similar than the individuals from a different community. Single-level data analysis does not take into consideration the hierarchical or nested structure of the data. Violation of the independence assumption may lead to underestimation of standard errors and inflation of type 1 errors (Uthman et al., 2018). Compared to a single level, the use of multilevel modelling permits cross-level analysis where level 2 predictors are used to predict a level 1 outcome. The use of aggregate level data without consideration of the individual level variation may lead to the ecological fallacy. The opposite is also true if only single-level data is used to capture the variation at an aggregated level (Diez, 2002). From the reviewed studies a greater proportion of the variation was accounted for by community-level factors while in other studies it was accounted for by individual-level factors.

Use of theories

Most of the reviewed studies did not apply any theoretical perspectives in guiding the studies. Out of the 35 reviewed studies, only 8 studies applied theories in the explanation of the relationship between the independent and the outcome variables. The social-ecological theory was used to explain intimate partner violence among females and acute respiratory infection among children under the age of five. The use of the ecological theory in multilevel modelling studies is applicable since it explains how different levels in society can have an impact on different demographic outcomes. For instance, in explaining acute respiratory infection among children the environment can influence the health of children (Adesanya & Chiao, 2016). Other studies used the theory by Mosley and Chen (1984) to explain infant and child mortality. The theory highlights a relationship between the survival of the child and the determinants at various levels such as individual, household and community levels (Mosley & Chen, 2003).

The economic demographic theory of divorce was used to explain family dissolution in Sub-Saharan Africa (Odimegwu et al., 2017b). The theory argues that being in a union and later deciding to end the union is a rational decision by an individual. The normative climate theory was employed to explain how community-level factors such as unemployment and poverty may lead to divorce (Odimegwu et al., 2017b).

However, some studies used various theoretical perspectives to explain the relationship between polygyny and child health or survival (Adedini & Odimegwu 2017). The study relied on three hypotheses by Smith-Greenaway and Trinitapoli (2014) which argued that resource dilution occurs in polygamous families since there exist many children and women. This is believed to lead to poor childhood nutrition which might result in diseases and deaths (Adedini & Odimegwu 2017). The constraints on resources might affect the use of maternal health care services in polygamous families compared to monogamous families. Polygamous families contribute to gender inequalities and this might affect the health of the child (Adedini & Odimegwu 2017).

A study that investigated the relationship between migration status, individual versus contextual factors and contraceptive use in Nigerian women (Akinyemi et al., 2017b) relied on various theoretical perspectives. It used a migration hypothesis indicating the disruption and adaptation of the migrants. The disruption perspective argues that the act of migration might impact the woman’s decision of using contraceptives (Chattopadhyay et al., 2006). This might lead to a situation where a migrant woman at a new destination might lack information or access to contraceptives. The adaptation part indicates that rural-to-urban migration may improve the use of contraceptives since the women adapt to a new environment which provides information on the benefits of using contraceptives (Chattopadhyay et al., 2006).

Limitations

This review had some limitations. The review only focused on articles that were published in English excluding other studies which might have used multilevel modelling in Africa. The review was based on studies that were not more than ten years old. Most of the articles reviewed were lacking contextual variables such as ethnicity, community norms, values and beliefs as well as political factors. This was due to the nature of secondary data used which did not include additional variables also important in the multilevel modelling of various demographic outcomes.

Research agenda

Based on this review, contextual factors are important in the explanation of the various demographic outcomes. The use of multilevel modelling in demographic research is vital as it moves away from analyzing individual-level factors but shows the importance of how contextual factors play a role in influencing various demographic outcomes. The contextual or community variables were generated from individual-level variables. There are some demographic outcomes such as divorce or family dissolution which have not been widely investigated. Data on family dissolution is available on the Demographic and Health Survey which can allow research on the effect of community-level factors on marital dissolution. This is an important demographic outcome considering that most families are going through various changes or transitions with divorce being one of them. Instead, health outcomes among children and women dominated the multilevel landscape in African demographic research. It is recommended that demographic studies that use multilevel modelling should include males. The inclusion of studies about males in demographic research is vital since males are dominant decision-makers in households in most African countries and their decision-making power affect some outcomes such as the reproductive health of females and child health. Studies should consider combining or merging the women’s and men’s data or using the couple's data in examining some of the demographic outcomes to identify the effect that men also have on the different demographic outcomes.

Most of the studies used secondary data from the Demographic and Health Survey. This is widely available international data that is used in demographic research in most countries in Africa. Only a few studies used primary data (Alemayehu et al., 2020; Azage et al., 2016) while two studies conducted in South Africa used census data (De Wet & Odimegwu, 2017; Zewdie & Adjiwanou, 2017) and one study used the Tanzania HIV and Malaria indicator survey (Adinan et al., 2017) and the other used the Uganda AIDS indicator survey (Igulot & Magadi, 2018). In Africa, there exist the Health and Demographic surveillance system (HDSS) which collects longitudinal data in specific parts of the countries which lack an effective vital registration system for registering vital events (Herbst et al., 2021). Future studies can use the HDSS to examine the effect of community-level factors on various demographic health outcomes considering that the type of data is detailed and allows retrospective and population-based studies to be conducted. The data allows for answering questions on cause and effect which cannot be attained using cross-sectional data.

There is a need for multilevel modelling studies that use other research designs such as longitudinal studies apart from the usual cross-sectional studies. This is because all the studies which were reviewed used a cross-sectional design and this type of design is limited in that causal inference between the community-level factors and the outcome variables cannot be made. The use of a longitudinal research design will be able to address the limitations of cross-sectional designs. However, there are limited longitudinal data in Africa due to the large resources associated with the collection of data. The Health and Demographic surveillance system in Africa has few research sites collecting longitudinal data which might explain the strong reliance on the Demographic and Health Survey (Herbst et al., 2021). There is also a need for more studies on multilevel modelling that investigate if and how factors at different levels interplay to affect health outcomes. Also, the studies which use multilevel modelling should focus on indicating how the method differs from other methods which only focus on fixed effects. The interpretation of results in the reviewed studies was mainly focused on fixed effects rather than random effects. Future studies on multilevel modelling should focus on the interpretation of both the fixed and random effects since what makes the method differ from others is its use of random effects in the explanation of the variation across communities. Failure to interpret the measures of variation undermines the whole purpose and goal of multilevel modelling which is to explain the variation of the demographic outcomes within the communities.

Some of the studies raised important suggestions that interventions should target educating communities about norms, beliefs and values which work against the immunization of children. This is important because mothers might know the importance of having their children immunized but other contextual factors might serve as barriers. This includes being denied permission by their partners to seek healthcare services.

The findings from the reviewed studies suggest the importance of devising policies that are not only based on the individual level but at the community level. There is a need for context-specific policies and programmes aimed at improving health outcomes among women and children. The sub-Saharan region is characterized by various traditional norms and cultural values which contribute to negative health outcomes. Dealing with such circumstances requires addressing the contextual factors and understanding that the health problems faced by individuals are deeply embedded within the communities they live in. Also, the existing health behaviours within communities are shaped by societal conditions and structures. Separating contextual factors from individual-level factors limits the understanding and tracing of social ills which impact health outcomes thereby hindering the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals. From this, it is evident that context matters, for sub-Saharan Africa to deal with the health problems it encounters the region needs to focus on community-level interventions. This is important considering that both individual and contextual factors are vital in shaping health behaviours.

Conclusion

The paper reviewed the use of multilevel modelling in demographic research in Africa. The studies have shown that multilevel modelling is good at dealing with hierarchically structured data. The reviewed studies showed how multilevel modelling is useful in explaining the role of community-level characteristics in various demographic outcomes. As shown in the studies through multilevel modelling, one can examine whether the variations between the groups affect all the groups or some specific sub-groups. The studies followed a similar methodological approach when applying multilevel modelling analysis in their studies, all the studies began with a null model and accounted for variation through the use of the Intra-class community correlation coefficient (ICC). The studies indicated how various models were built in multilevel modelling to illustrate how community-level characteristics can affect the outcome variable.

In the studies, multilevel modelling was able to answer research questions on how community-level characteristics are related to various demographic outcomes after controlling for individual-level characteristics. For instance, different African countries in sub-Saharan Africa highlighted similar community-level factors which influence childhood immunization, child mortality, low birth weight and contraceptive use. The community-level factors such as poverty, level of education, region or place of residence, community delivery and distance to health facilities had an impact on various demographic outcomes. These findings illustrate a myriad of problems in Africa and highlight that interventions should be done at the community level to address the issues raised in the studies. For research and analytic purposes, multilevel modelling remains relevant, especially for the longitudinal investigation of temporal relationships at individual and contextual levels.

Data availability

Not applicable the research is a systematic review.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Abadura, S. A., Lerebo, W. T., Kulkarni, U., & Mekonnen, Z. A. (2015). Individual and community level determinants of childhood full immunization in Ethiopia: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health, 15(1), 972. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2315-z

Acharya, P., Kismul, H., Mapatano, M. A., & Hatløy, A. (2018). Individual-and community-level determinants of child immunization in the Democratic Republic of Congo: A multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE, 13(8), e0202742. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0202742

Adedini, S. A., & Odimegwu, C. (2017). Polygynous family system, neighbourhood contexts and under-five mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Development Southern Africa, 34(6), 704–720. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1310030

Adedini, S. A., Odimegwu, C., Imasiku, E. N., Ononokpono, D. N., & Ibisomi, L. (2015). Regional variations in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. Journal of Biosocial Science, 47(2), 165–187. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932013000734

Adedokun, S. T., Adekanmbi, V. T., Uthman, O. A., & Lilford, R. J. (2017a). Contextual factors associated with health care service utilization for children with acute childhood illnesses in Nigeria. PLoS ONE, 12(3), e0173578. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0173578

Adedokun, S. T., Uthman, O. A., Adekanmbi, V. T., & Wiysonge, C. S. (2017b). Incomplete childhood immunization in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health, 17(1), 236. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-017-4137-7

Adekanmbi, V. T., Kayode, G. A., & Uthman, O. A. (2013). Individual and contextual factors associated with childhood stunting in Nigeria: A multilevel analysis. Maternal & Child Nutrition, 9(2), 244–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1740-8709.2011.00361.x

Adesanya, O. A., & Chiao, C. (2016). A multilevel analysis of lifestyle variations in symptoms of acute respiratory infection among young children under five in Nigeria. BMC Public Health, 16(1), 880. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3565-0

Adinan, J., Damian, D. J., Mosha, N. R., Mboya, I. B., Mamseri, R., & Msuya, S. E. (2017). Individual and contextual factors associated with appropriate healthcare seeking behavior among febrile children in Tanzania. PLoS ONE, 12(4), e0175446. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0175446

Ahinkorah, B. O. (2020). Individual and contextual factors associated with mistimed and unwanted pregnancies among adolescent girls and young women in selected high fertility countries in sub-Saharan Africa: A multilevel mixed effects analysis. PLoS ONE, 15(10), e0241050.

Akinyemi, J. O., Adedini, S. A., & Odimegwu, C. O. (2017a). Individual v community-level measures of women’s decision-making involvement and child survival in Nigeria. South African Journal of Child Health, 11(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.7196/SAJCH.2017.v11i1.1148

Akinyemi, J. O., Odimegwu, C. O., & Adebowale, A. S. (2017b). The effect of internal migration, individual and contextual characteristics on contraceptive use among Nigerian women. Health Care for Women International. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399332.2017.1345908

Akombi, B. J., Agho, K. E., Merom, D., Hall, J. J., & Renzaho, A. M. (2017). Multilevel analysis of factors associated with wasting and underweight among children under-five years in Nigeria. Nutrients, 9(1), 44.

Alemayehu, M., Medhanyie, A. A., Reed, E., & Mulugeta, A. (2020). Individual-level and community-level factors associated with the family planning use among pastoralist community of Ethiopia: A community-based cross-sectional study. British Medical Journal Open, 10(9), e036519.

Antai, D. (2011). Regional inequalities in under-5 mortality in Nigeria: A population-based analysis of individual- and community-level determinants. Population Health Metrics, 9, 6. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-7954-9-6

Azage, M., Kumie, A., Worku, A., & Bagtzoglou, A. C. (2016). Childhood diarrhea in high and low hotspot districts of Amhara Region, northwest Ethiopia: A multilevel modeling. Journal of Health, Population and Nutrition, 35(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41043-016-0052-2

Chaix, B., & Chauvin, P. (2002). The contribution of multilevel models in contextual analysis in the field of social epidemiology: A review of literature. Epidemiology and Public Health/revue D’epidémiologie Et De Santé Publique, 50, 489–499.

Chattopadhyay, A., White, M. J., & Debpuur, C. (2006). Migrant fertility in Ghana: Selection versus adaptation and disruption as causal mechanisms. Population Studies, 60(2), 189–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324720600646287

Courgeau, D. (2007). Multilevel synthesis: from the group to the individual (Vol. 18). Springer Science & Business Media.

Dankwah, E., Feng, C., Kirychuck, S., Zeng, W., Lepnurm, R., & Farag, M. (2021). Assessing the contextual effect of community in the utilization of postnatal care services in Ghana. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–18.

De Wet, N., & Odimegwu, C. (2017). Contextual determinants of adolescent mortality in South Africa. African Health Sciences, 17(1), 62–69. https://doi.org/10.4314/ahs.v17i1.9

Diez, R. (2002). A glossary for multilevel analysis. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 56(8), 588.

Diez-Roux, A. V. (2000). Multilevel analysis in public health research. Annual Review of Public Health, 21(1), 171–192. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.publhealth.21.1.171

Duncan, C., Jones, K., & Moon, G. (1998). Context, composition and heterogeneity: Using multilevel models in health research. Social Science & Medicine, 46(1), 97–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(97)00148-2

Ejembi, C. L., Dahiru, T., & Aliyu, A. A. (2015). Contextual factors influencing modern contraceptive use in Nigeria https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP120/WP120.pdf.

Ekouevi, D. K., Gbeasor-Komlanvi, F. A., Yaya, I., Zida-Compaore, W. I., Boko, A., Sewu, E., et al. (2018). Incomplete immunization among children aged 12–23 months in Togo: A multilevel analysis of individual and contextual factors. BMC Public Health, 18(1), 952. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-5881-z

Fuse, K. (2010). Variations in attitudinal gender preferences for children across 50 less-developed countries. Demographic Research, 23, 1031–1048. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.36

Herbst, K., Juvekar, S., Jasseh, M., Berhane, Y., Chuc, N. T. K., Seeley, J., & Collinson, M. A. (2021). Health and demographic surveillance systems in low-and middle-income countries: history, state of the art and future prospects. Global Health Action, 14(sup1), 1974676.

Igulot, P., & Magadi, M. A. (2018). Social and structural vulnerability to HIV infection in Uganda: A multilevel modelling of AIDS indicators survey data, 2004–2005 and 2011. Journal of Community Medicine. https://doi.org/10.33582/2637-4900/1008

Kayode, G. A., Amoakoh-Coleman, M., Agyepong, I. A., Ansah, E., Grobbee, D. E., & Klipstein-Grobusch, K. (2014). Contextual risk factors for low birth weight: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE, 9(10), e109333. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0109333

Kreft, I. G., Kreft, I., & de Leeuw, J. (1998). Introducing multilevel modeling. Sage.

Mohan, D., Gupta, S., LeFevre, A., Bazant, E., Killewo, J., & Baqui, A. H. (2015). Determinants of postnatal care use at health facilities in rural Tanzania: Multilevel analysis of a household survey. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 15(1), 1–10.

Mekonnen, Z. A., Lerebo, W. T., Gebrehiwot, T. G., & Abadura, S. A. (2015). Multilevel analysis of individual and community level factors associated with institutional delivery in Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes, 8(1), 376. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13104-015-1343-1

Mosley, W. H., & Chen, L. C. (1984). An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Population and Development Review, 10, 25–45.

Mosley, W. H., & Chen, L. C. (2003). An analytical framework for the study of child survival in developing countries. Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 81(2), 140–145.

Ngome, E., & Odimegwu, C. (2014). The social context of adolescent women’s use of modern contraceptives in Zimbabwe: A multilevel analysis. Reproductive Health, 11(1), 64. https://doi.org/10.1186/1742-4755-11-64

Odimegwu, C., & Chemhaka, G. B. (2021). Contraceptive use in Eswatini: Do contextual influences matter? Journal of Biosocial Science, 53(1), 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932019000889

Odimegwu, C., Somefun, O. D., & De Wet, N. (2017a). Contextual determinants of family dissolution in sub-Saharan Africa. Development Southern Africa. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1310029

Odimegwu, C., Somefun, O. D., & De Wet, N. (2017b). Contextual determinants of family dissolution in sub-Saharan Africa. Development Southern Africa, 34(6), 721–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/0376835X.2017.1310029

Olanrewaju, J. A., Kona, H. U., & Dickson, T. U. (2015). The dilemma of male child preference Vis-à-vis the role of women in the Yoruba traditional religion and society. Journal of Culture, Society and Development, 12, 87–93.

Ononokpono, D. N., & Odimegwu, C. O. (2014). Determinants of maternal health care utilization in Nigeria: a multilevel approach. The Pan African Medical Journal. https://doi.org/10.11694/pamj.supp.2014.17.1.3596

Ononokpono, D. N., Odimegwu, C. O., Imasiku, E., & Adedini, S. (2013). Contextual determinants of maternal health care service utilization in Nigeria. Women & Health, 53(7), 647–668. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2013.826319

Ononokpono, D. N., Odimegwu, C. O., & Usoro, N. A. (2020). Contraceptive use in Nigeria: Does social context matter?. African Journal of Reproductive Health, 24(1), 133–142.

Oyediran, K., & Feyisetan, B. (2017). Prevalence and contextual determinants of intimate partner violence in Nigeria. African Population Studies. https://doi.org/10.11564/31-1-1003

Parr, N. (1999). Applications of Multilevel Models in Demography: What have we learned? Macquarie University.

Rossi, P., & Rouanet, L. (2015). Gender preferences in Africa: A comparative analysis of fertility choices. World Development, 72, 326–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.03.010

Rowland, D. T. (2003). Demographic methods and concepts. OUP Oxford.

Smith-Greenaway, E., & Trinitapoli, J. (2014). Polygynous contexts, family structure, and infant mortality in sub-Saharan Africa. Demography, 51(2), 341–366. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-013-0262-9

Solanke, B. L., Amoo, E. O., & Idowu, A. E. (2017). Improving postnatal checkups for mothers in West Africa: A multilevel analysis. Women & Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/03630242.2017.1292343

Uchudi, J., Magadi, M., & Mostazir, M. (2012). A multilevel analysis of the determinants of high-risk sexual behaviour in sub-Saharan Africa. Journal of Biosocial Science, 44(3), 289–311. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932011000654

Uthman, O. A., Sambala, E. Z., Adamu, A. A., Ndwandwe, D., Wiyeh, A. B., Olukade, T., et al. (2018). Does it really matter where you live? A multilevel analysis of factors associated with missed opportunities for vaccination in sub-Saharan Africa. Human Vaccines & Immunotherapeutics, 14(10), 2397–2404. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2018.1504524

Wiysonge, C. S., Uthman, O. A., Ndumbe, P. M., & Hussey, G. D. (2012). Individual and contextual factors associated with low childhood immunisation coverage in sub-Saharan Africa: a multilevel analysis. PLoS ONE, 7(5), e37905. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0037905

Yebyo, H. G., Gebreselassie, M. A., & Kahsay, A. B. (2014). Individual and community level predictors of home delivery in Ethiopia: A multilevel mixed effects analysis of the 2011 Ethiopia national demographic and health survey. DHS Working Papers. Rockville, Maryland: ICF International. Retrieved 17, August 2019, from https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/WP104/WP104.pdf

Zaccarin, S., & Rivellini, G. (2002). Multilevel analysis in social research: An application of a cross-classified model. Statistical Methods & Applications, 11(1), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02511448

Zegeye, B., Ahinkorah, B. O., Idriss-Wheeler, D., Olorunsaiye, C. Z., Adjei, N. K., & Yaya, S. (2021). Modern contraceptive utilization and its associated factors among married women in Senegal: A multilevel analysis. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1–13.

Zewdie, S. A., & Adjiwanou, V. (2017). Multilevel analysis of infant mortality and its risk factors in South Africa. International Journal of Population Studies, 3(2), 43–56. https://doi.org/10.18063/ijps.v3i2.330

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of the Witwatersrand. Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Clifford contributed to the conceptualisation and discussion of the study. Marifa and Joshua contributed in conducting a literature search and write-up.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics approval

Not applicable.

Consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

All three authors give consent.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Odimegwu, C., Muchemwa, M. & Akinyemi, J.O. Systematic review of multilevel models involving contextual characteristics in African demographic research. J Pop Research 40, 10 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09305-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-023-09305-y