Abstract

The stress partitioning between phases, phase stress relaxation as well as origins of Al/SiCp composite strengthening are studied in the present work. In this aim, the measurements of lattice strains by neutron diffraction were performed in situ during tensile test up to sample fracture. The experimental results were compared with results of elastic–plastic self-consistent model. It was found that thermal origin phase stresses relax at the beginning of plastic deformation of Al/SiCp composite. The evolution of lattice strains in both phases can be correctly simulated by the elastic–plastic self-consistent model only if the relaxation of initial stresses is taken into account. A major role in the strengthening of the studied composite plays a transfer of stresses to the SiCp reinforcement, however the hardness of Al metal matrix is also important.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Metal Matrix Composites (MMC) are an interesting alternative to classical alloys. Their superior mechanical properties—in comparison to classical alloys—are their unique stiffness, high specific strength and/or ductility, as well as improved wear resistance. The strengthening mechanism of the MMC is obtained by: the addition of reinforcements which possess definitely superior mechanical properties than the matrix and by locking dislocation movement which depends on the mechanical properties, geometry and space distribution of the constituents [1].

The Al/SiCp composite studied in this work consists of the Al2124 aluminium alloy matrix with silicon carbide particles reinforcement. Aluminium is a material of relatively low density and high ductility, but the limitation for its application is caused by relatively low strength, hardness, stiffness and tribological properties [2, 3]. However, strength and hardness of aluminium can be improved through alloying and heat treatment leading to precipitation or age hardening by the phases precipitated in a solid state reaction, as is in the case of the classical Al-Cu-Mg alloys, or through the strengthening by particles insoluble during the powder compaction technology, as in the case of the composites reinforced by silicon carbide particles.

In the present work the mechanical behaviour of the Al/SiCp composite was studied using neutron diffraction. The advantage of diffraction methods is that the mechanical behaviour of different phases of polycrystalline material can be independently studied during sample loading [cf. 4–10]. This method enables measuring of the lattice strains/stresses selectively for Al-matrix and SiCp—reinforcement constituents, only for the crystallites contributing to the recorded diffraction peaks [cf. 11–14]. The results of neutron experiment are usually analysed and interpreted using elastic–plastic models.

The elastic–plastic behaviour of Al/SiCp composites has already been studied using the finite element method (FEM) [15,16,17,18] and the influence of the SiCp reinforcement on the overall elastic–plastic properties including stress relaxation during reinforcement fraction [17] and decohesion processes [18] were predicted. The Eshelby type models [19] were also applied to calculate the stress in the ellipsoidal reinforcement inclusion and in the metal matrix [20,21,22,23,24]. The results of the elastic–plastic self-consistent (EPSC) model were successfully compared with diffraction measurements in which the lattice strains in both phases were determined during the bending test [24]. It was shown that the EPSC model correctly predicts the behaviour of the particle reinforced MMC and the stress partitioning between phases in the case of relatively low content of the reinforcement. Both the diffraction measurements performed for a large sample volume as well as the self-consistent model provide statistical information concerning the mean strains/stresses for groups of crystallites and phases, but the spatial heterogeneities of these quantities in the matrix cannot be studied using these methods.

The lattice strains in both phases of Al/SiCp composite were already measured in situ during heat treatment [25], during elastic–plastic loading [14, 24] and evolution of residual stresses was determined after thermal or mechanical treatments [13, 26]. A significant influence on stress partitioning between phases was also determined using diffraction during damage process [27, 28]. The interpretation of the diffraction data using Eshelby type models (including self-consistent method) showed that important mismatch stresses are induced during composite cooling due to the difference in thermal expansion coefficient of the phases [29]. These stresses can be significantly modified by plastic deformation [30] or combination of thermal and mechanical treatments [31] long before damage of the material. The release/modification of the residual phase stresses is of vital importance due to their influence on fatigue cracking process in MMC [32].

The aim of this work is the study of mechanical behaviour of the Al matrix and SiCp reinforcement in the Al/SiCp composite using neutron diffraction in situ during tensile test. The interpretation of the experimental results is done by comparing the measured lattice strains and overall mechanical behaviour of the composite with predictions of the EPSC model. The focus of the present investigation is put mainly on the evolution of phase stresses during external loading of the sample, including process of stress relaxation. The neutron diffraction measurements analysed with the help of EPSC model are used to determine a value of tensile sample strain for which hydrostatic thermal stresses are released. Finally, the mechanical properties of the matrix and reinforcement and their influence on the strengthening of the composite are determined.

2 Experiment and Model Prediction

2.1 Materials

Materials tested in this work are the Al2124 alloys (Table 1) either unreinforced or reinforced with SiC particles. The Al/SiCp composite produced by powder metallurgy route was provided by Materion Aerospace Metal Composites, Farnborough, Hampshire, UK. This technique is based on blending and compaction of mixed aluminium and SiC powders. The amount of the reinforcement particles in the composite is 17.8% by volume and the particle average size is 0.7 μm.

Two types of the material with different heat treatments were studied. The first one was subjected to the T6 heat treatment (i.e. solution treatment at 491 °C for 6 h and then cold water quenching to produce a supersaturated solid solution, and finally artificial aging for 4 h at 191 °C). This treatment resulted in the hardening of the Al2124 alloy by semi-coherent Cu-Al–Mg precipitates [33]. The second part of the composite was subjected to the T1 heat treatment, consisting in the natural aging with a calm air cooling directly after 6 h annealing at 491 °C. In this work, the composite specimens subjected to the heat treatments T6 and T1 are marked respectively Al/SiCp-T6 and Al/SiCp-T1, while the unreinforced aluminium alloy sample subjected to T6 treatment is labelled as Al2124-T6.

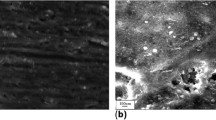

In Fig. 1, the SEM image of the examined Al/SiCp specimen is presented. A significant dispersion of the particles size around the nominal value 0.7 µm and their not perfectly uniform spatial distribution can be observed. However, in the case of the relatively large gauge volume in the diffraction experiment, a macroscopically homogeneous material was assumed in this study.

The crystal structure and crystallographic texture of the composite phases were determined on the Panalytical Empyrean diffractometer using Cu Kalpha X-ray radiation. The Rietveld analysis of the experimental results showed that the 6H polytype with hexagonal structure is dominant (content of ca. 80%) in the investigated SiC powder (used as a reinforcement in the composite), while the aluminium alloy Al2124 exhibits a face centred cubic structure. No significant crystallographic texture was found in both phases of the composite.

2.2 Neutron Diffraction Measurements

The lattice strains in the studied materials were measured using a time of flight (TOF) neutron diffraction method on the EPSILON-MDS and FSD diffractometers [34, 35] installed at the IBR-2 pulsed reactor in the JINR in Dubna (Russia). The example diffractograms obtained using both instruments are shown in Fig. 2. On the FSD diffractometer the evolutions of crystal structure and coefficients of thermal expansion at temperature range 22 °C-500 °C were investigated for the SiC powder and the Al2124 alloy [36]. It was found that in the investigated range of the temperature crystallographic structure of SiC powder does not change and the increase of lattice parameter is caused by thermal expansion of the material (Fig. 2b, [36]).

The main experiments were performed on the EPSILON-MDS diffractometer (at ambient temperature) using two configurations presented in Fig. 3. The first configuration with two detectors L2 and L8 (other detectors were shaded by the tensile rig) was applied during the in situ tensile test for the dog-bone shaped samples having a square cross section 4 mm × 4 mm and a gauge length of 15 mm. The specimens were cut using the electrical discharge machining (EDM) method in such a way that the sample axes were parallel to the sheet edges. The applied loads were measured in situ by load cell and the macroscopic strain was determined ex situ by an extensometer connected to an identical sample subjected to the same loads. To obtain satisfactory counting statistics, the diffraction measurements through the whole cross section of the sample were done using the wide incident beam with an aperture of 10 mm. The diffraction measurements were performed for constant grip positions (corresponding to given sample strains), after stabilisation of the applied load, which decreased over a period of about ½ h. Both composite samples (Al/SiCp-T1 and Al/SiCp-T6) fractured very close to the macroscopic strain of E11 = 3% and in such a case the last diffraction measurement was done on the broken sample. Consequently, the last measurement of unreinforced alloy Al2124-T6 was also performed after the sample unloading at E11 = 3%.

The interplanar spacings in both phases were determined from the diffractograms (e.g. Figure 2b) by fitting of pseudo-Voigt function to the measured diffraction peaks. The relative lattice strains in direction of the load \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{{\{ hkl\} }}\) and in the transverse direction \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{22} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ hkl\right\} }}\) were calculated using Eq. 1:

where \(\left\langle d \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}^{\varSigma }\) and \(\left\langle d \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}^{0}\) are the interplanar spacings determined for the loaded (for given applied stress \(\varSigma_{11}\)) and non-loaded sample (initial, i.e. for \(\varSigma_{11} = 0\)) and the <…>{hkl} brackets denotes an average over the diffracting grains volume for a given reflection hkl. Indices LD and TD mean that the interplanar spacing were measured in the direction of the applied load and in the transverse direction, respectively.

Additionally, the ex situ diffraction measurements were performed for the initial as well deformed/fractured samples using the second configuration with nine detector banks arranged around the sample at the EPSILON-MDS diffractometer (L1–L9) as shown in Fig. 3b [34]. In this case the tensile machine was removed and the measurements were performed for two sample positions, the first at the orientation shown in Fig. 3 and the next after rotation by 90° around the sample long axis. In principle, the measurements of interplanar spacings for 18 orientations enable determining of the stress tensor for each phase if the strain free lattice parameters are known.

2.3 Elastic–Plastic Self-Consistent Model

In this work, the prediction of stresses evolution during elastic–plastic processes was done using the EPSC model proposed by Lipinski and Berveiller [37, 38] and applied to two phase materials by Baczmanski et al. [7, 24]. This model is based on the interaction of the grains with the surrounding matrix described by Eshelby tensor [19]. The model predictions were performed for a set of 2000 spherical grains representing 17.8% volume fraction of SiC reinforcement (356 grains) and 82.2% of the Al matrix (1644 grains). Because of weak crystallographic textures, the orientations of grain lattice were randomly generated and corresponding single crystal elastic constants were assigned to the grains of both phases (cf. Table 2). The spherical inclusions and zero initial stresses were assumed for the particles of SiC reinforcement and for the Al2124 matrix.

The elastic–plastic deformation with slip systems <110> {111} were assumed for aluminium, while only elastic deformation was assumed for SiC grains. Predictions of a tensile test were performed for various values of the critical resolved shear stress (CRSS, \(\tau_{c}\)) and the hardening parameter (H) of the Al2124 matrix [7, 24, 37, 38] (assuming linear and isotropic work hardening process for small deformations). The optimal values of \(\tau_{c}\) and H were determined by comparing the experimental and theoretical lattice strain evolutions for all the measured reflections, as well as macroscopic dependence of overall stress versus sample strain. The same procedure of experimental data analysis was carried out for the Al2124-T6 alloy, but in this case the single phase polycrystalline aggregate consisting of 2000 aluminum grains was considered.

3 Results

3.1 Macroscopic Behaviour of the Al/SiCp Composite and Al2124 Alloy

Firstly, the dependence of the applied stress versus sample strain was analysed in order to choose the best model parameters. In Fig. 4a the macroscopic plots obtained in the tensile test for the Al2124-T6 alloy and Al/SiCp-T6 composite are compared with the prediction of the EPSC model. The values of \(\tau_{c}\) and H for slip system <110> {111} were adjusted in order to fit the theoretical macroscopic stress–strain plot to the experimental one obtained for the Al2124-T6 alloy. A very good convergence of the model and experimental plots both in the elastic and plastic ranges of deformation was obtained for the elastic constants given in Table 2 and plastic slip system parameters shown in Table 3. Next, the properties of the unreinforced Al2124-T6 alloy were assumed for the matrix of the Al/SiCp-T6 composite (cf. the T6 treatment in Table 3), and the tensile test was predicted for this composite, using elastic constant of the 6H-SiC polytype given in Table 2. It was found that the EPSC model correctly predicts elastic and plastic deformation of the studied composite at a macroscopic scale (Fig. 4a), when the CRSS and hardening parameter determined for Al2124-T6 alloy (Table 3) are used for the matrix.

Overall stress versus sample strain (a) and von Mises stresses in phases (b) in the tensile test performed for the Al2124-T6 alloy without reinforcement and the Al/SiCp-T6 composite. The experimental results are compared with EPSC prediction for single crystal elastic constants given in Table 2 and plastic parameters presented in Table 3

Using the model prediction, the role of SiCp in the hardening of Al/SiCp was also studied. To do this, the evolution of von Mises stress calculated for each phase within the Al/SiCp-T6 composite as well as for the Al2124-T6 alloy are shown in Fig. 4b. It was found that this stress changes almost identically in the Al2124-T6 alloy (without reinforcement) and in the same alloy creating matrix of the Al/SiCp-T6 composite, i.e. the theoretical curves representing aluminium overlap and agree with the experimental ones obtained for the unreinforced Al2124-T6 alloy. This means that the SiCp particles do not cause significant hardening of the aluminium matrix. The overall macrostress for the composite is much higher comparing with Al2124-T6 alloy exclusively due to large stress accumulated in elastically deformed SiCp reinforcement, as shown in Fig. 4b. It should be emphasized, however, that until now no experimental information on the state of stresses in SiCp is provided, therefore the stress partitioning between the composite phases is shown in Sect. 3.3.

The analysis of the macroscopic stress versus strain dependence was performed also for the Al/SiCp-T1 composite. It was found that the value of the CRSS determined from the EPSC model adjustment to the macroscopic curves (Fig. 5) is much lower for the T1 treatment in comparison with that for the T6 treatment, while the hardening parameter H is similar for both treatments (cf. Table 3). The macroscopic stress versus strain plots (Fig. 5) showed an important influence of the matrix state on the overall mechanical behaviour of the composite, which is much softer after the T1 treatment than after the T6 treatment.

Macroscopic dependence of macroscopic stress (after stabilisation) versus macroscopic strain for the Al/SiCp (T1 and T6) composite subjected to tensile tests. The experimental results are compared with EPSC prediction for single crystal elastic constants given in Table 2 and plastic parameters presented in Table 3

3.2 Relaxation of Thermally Induced Stresses

Here, the analysis of phase stresses in the initial and fractured composite specimens is presented (based on results of the ex situ measurement with nine detectors, Fig. 3b). Data analysis was performed with the Kröner-Eshelby model used for calculation of the X-ray elastic constants (XECs) for each phase separately [42]. In the case of 6H-SiC, the diffraction peaks for 006/102, 108/110 and 116/202 reflections were measured, while for the Al2124 matrix—111, 200, 220, 311 and 220 reflections were taken into account. The stress values were calculated on the basis of experimental data using the least square method in which the three principal stress components were adjusted, while the shear stresses were neglected due to symmetry of the sheet from which the samples were cut. The measurements at elevated temperatures up to 500 °C (cf. Fig. 2a and [36]) performed for 6H-SiC powder showed that the structure of SiCp did not change during T1 and T6 heat treatments. Therefore the stress free interplanar spacings of the SiCp reinforcement were assumed to be equal to these measured at room temperature for the same silicon carbide powder that was used in the production of the composite. In the case of the composite matrix, the accurate value of the stress free lattice parameter (\(a_{0}\)) is influenced by the precipitation process occurring in the Al2124 alloy. Consequently, the value of \(a_{0}\) measured for the unreinforced Al2124 alloy (or powder) cannot be used in stress analysis for the matrix, because during thermal treatments the precipitation process can proceed differently in the unreinforced and reinforced alloy [36].

The stress analysis was based on the decomposition of the stress tensor into two parts, containing the hydrostatic component (p) and deviatoric components (\(q\), \(r\), \(s\)):

The deviatoric stresses were correctly determined for both phases because they do not depend on the values of the stress free lattice parameters. Also, the value of hydrostatic stress p for SiCp reinforcement, based on the lattice parameters determined for SiC powder, can be determined. Because the stress free lattice parameter for the composite matrix subjected to the given heat treatment is not available, the hydrostatic stress in the matrix should be deduced from the equilibrium law for the non-loaded sample:

where f = 0.178 is a volume fraction of SiCp and the above law is fulfilled for all stress components as well as for deviatoric and hydrostatic stresses.

In stress analysis performed for aluminium matrix, an approximated value of \(a_{0}\) was temporarily assumed. Then, the determined hydrostatic stresses were adjusted by shifting p by the same value simultaneously for the results obtained for the initial and fractured samples in order to fulfil Eq. 3. This correction corresponds to the adjustment of \(a_{0}\) value for both states (initial and fractured), subjected previously to the same heat treatment. The so-obtained stresses for all specimens examined during the tensile test and for both phases are presented in Tables 4 and 5, for the Al/SiCp-T1 and Al/SiCp-T6 specimens, respectively. It was found that the mean p values calculated over both phases (according to Eq. 3) are approximately equal to zero within the uncertainty range, simultaneously for the initial and deformed samples. This condition is fulfilled for both materials subjected to the treatments T6 and T1 (cf. the first columns in Tables 4, 5). An evolution of the hydrostatic stresses during deformation was also calculated from relative changes of interplanar spacings for the deformed sample with respect to the initial one. Although the latter method does not allow for calculating the absolute values of the hydrostatic stresses, however in the calculations of the relative changes of these stresses \((\Delta p)\) the values of \(a_{0}\) are not required. As shown in the second columns of Tables 4 and 5, the \(\Delta p\) values are very close to the differences between the hydrostatic stresses p for the deformed and initial samples (cf. the first columns). Moreover, the equilibrium law (Eq. 3) applied to the \(\Delta p\) values gives the mean value close to zero (within uncertainty range), i.e. the equilibrium condition is fulfilled. Therefore, it can be concluded that the values of the hydrostatic stresses p and their changes \(\Delta p\), are correctly determined.

As shown in Tables 4 and 5 the deviatoric phase stresses and their evolution are less significant, when compared with the hydrostatic ones. It was found that the large hydrostatic compressive stress in SiCp reinforcement and tensile stress in aluminium matrix were generated during T1 or T6 treatment. This effect is caused by a difference in coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) for the composite components (Table 2), leading to larger volume contraction for aluminium matrix comparing with particles of SiCp, during the cooling process. On the other hand, small deviatoric stresses in the initial sample are caused by possible temperature gradients in the heat treated sheets as well as plastic deformation during sample machining. Also, it should be stated that the equilibrium condition (Eq. 3) is not strictly fulfilled for the components of deviatoric stresses in the initial samples, probably due the relatively large experimental uncertainties, comparing to small values of these stresses. More pronounced deviatoric stresses, resulting from phase interaction during plastic deformation, were measured after tensile test. The components of the latter stresses in some approximation fulfil equilibrium condition.

Analysing the results presented in Tables 4 and 5, it can concluded that an important decrease in hydrostatic compressive stress occurred in the SiCp reinforcement corresponding to the relaxation of initially large thermal stress. Also, the decrease in the hydrostatic part of the mean tensile stress in the Al2124 matrix has been observed as a consequence of stress relaxation around the SiCp inclusions. The process of stress relaxation has been studied post factum for the already fractured sample, but it is interesting to determine when this phenomenon start to occur. To solve this problem, it is necessary to follow the evolution of the stresses and lattice strains measured in situ during the deformation tests.

3.3 Evolution of Lattice Strains in the Al/SiCp Composite and Al Alloy

The lattice strain evolutions in the Al and SiCp phases along the direction of applied load \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) and in the perpendicular direction \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{22} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) (Eq. 1) were determined in situ using configuration with two detectors shown in Fig. 3a and compared with EPSC model (Figs. 6, 7, 8). Model calculations were performed up to the maximum sample strain (i.e. E11 = 3%), followed by sample fracture/unloading with values of the CRSS \((\tau_{c} )\) and hardening parameter (H), determined previously for the studied materials on the basis of the mechanical curves (Table 3). It should be mentioned that the macrostrains of the fractured composite samples were unknown, therefore the experimental points (lattice strains) for the broken samples were placed in Figs. 7 and 8 close to the plastic macrostrain predicted by model after unloading of the sample.

Lattice strains measured for different reflections hkl (points) during tensile test are compared with the EPSC modelling (lines) performed for the parameters given in Tables 2 and 3. The lattice strains in loading direction (a) and perpendicular direction (b) are presented as functions of macrostrain

The experimental and model mean lattice strains along the loading direction \(\left\langle {\upvarepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{\text{mean}}^{{}}\) in both phases of Al/SiC-T6 (a) and Al/SiC-T1 (b) samples, calculated as the average over 200, 111, 220, 311 reflections in Al and over 006/102, 108/110, 202/116 reflections in SiC. The model results were computed for parameters given in Tables 2 and 3, starting from initial stresses or assuming zero initial stresses

The lattice strains along the loading direction \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}^{{}}\) and perpendicular direction \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{22} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}^{{}}\) in both phases of Al/SiC-T6 sample compared with the modelling performed for the parameters given in Tables 2 and 3. The model results starting from initial stresses are shown on the left of the relaxation line, while the results assuming relaxed initial stresses are shown on the right

A very good result of the experiment—model comparison was found for the relative lattice strains (cf. Eq. 1) measured for the Al2124-T6 specimen under the tensile load both in the elastic and elastic–plastic range of deformation up to E11 = 3%. The model predicted values of lattice strains are slightly overestimated during the tensile test, but for the unloaded sample the modelling calculations hit the experimental points correctly (Fig. 6). The lattice strain evolution for different hkl reflections confirms that the EPSC model correctly predicts the partitioning of stresses between the grains in the Al2124-T6 alloy and well reproduces the anisotropy of plastic deformation for the different groups of grains, cf. [9, 42,43,44].

To solve the problem of stress partitioning between phases, the lattice strains measured in situ in the SiCp and in Al2124 constituents of the composite during the tensile test were analysed. The important influence of the evolution of mean values of lattice strain along loading direction measured for reflections 200, 111, 220, 311 in aluminium matrix and for reflections 006/102, 108/110, 202/116 in SiC reinforcement is visible in Fig. 7. In this figure, the results for the sample subjected to the treatments T6 and T1 are shown. The experimentally measured relative lattice strains were determined using Eq. 1 and then the strains caused by initial stresses (cf. Tables 4, 5) were superimposed. Subsequently, the lattice strains were calculated using the EPSC model with two assumptions, i.e. accounting for the initial stresses given in Tables 4 and 5 or setting zero stresses for both phases.

Analysing Fig. 7, it was found that for the elastic deformation, a good agreement between the experiment and model was obtained taking into account the initial stresses, while for the further elastic–plastic deformation much better accordance was observed with zero initial stress assumption (cf. Fig. 7). Therefore, it can be concluded that the initial phase stresses relax at very small tensile deformation (ca. 0.2%–0.8%), and consequently do not influence further stress partitioning and mechanical behaviour of the composite phases. The residual lattice strains in both phases (last points in Figs. 7, 8 obtained for the fractured samples) are also well predicted by the model, assuming zero initial stresses. This results agree well with previous works showing relaxation and complete exchange of stress state in the Al/SiCp composite and also in other materials subjected to plastic deformation [11, 13, 30, 31]. The new finding of the present work is that the stress relaxation occurs very early i.e. for a small elastic–plastic deformation, close to the yield point of the matrix. It should be also emphasised that the EPSC model does not predict the relaxation of initial phase stresses having mostly a hydrostatic character. This is why in the present research two assumptions were used (i.e. the material with and without initial stresses) to model the complete history of the tensile test.

Finally, in Fig. 8 the lattice strains for individual reflections hkl in both phases of Al/SiC-T6 sample, measured along applied load and in the transverse direction, are shown. The experimental results agree with the model prediction if in the calculation the initial stresses are taken into account for the beginning of deformation (up to about E11 = 0.5% of sample strain), and zero initial stress is assumed for further deformation (above about E11 = 0.5% of sample strain). This can be explained due to the discussed above relaxation of initial stresses in the beginning of plastic deformation.

4 Discussion

The reason for interphase stresses in the initial samples is a difference in coefficient of thermal expansion (CTE) values for the composite components (Table 2). As shown in Tables 4 and 5, in the samples subjected to T1 and T6 treatments, a hydrostatic compressive stresses in the SiCp phase appeared as a result of the significant decrease in the Al2124 matrix volume compared with much smaller decrease in SiCp particle volume during cooling of the material. This stress must be balanced by the average tensile stress in the Al2124 matrix being a response to the hydrostatic stresses generated in SiCp. It should also be emphasised that similar values of hydrostatic phase stresses were found in both specimens subjected to the T1 and T6 treatments, because both materials were cooled down from the same solution treatment temperature of 491 °C. After T1 treatment, slightly smaller hydrostatic stresses were found, but the difference from the T6 treatment is not significant when compared with experimental uncertainties (Tables 4, 5). It means that the different types of ageing did not significantly influence thermally induced stresses which were originated mostly from important differences in thermal contraction of Al2124 and SiC phases.

A comparison of the stresses in the initial Al/SiCp specimens (after T1 or T6 treatments) with those in the deformed ones (after fracture in the tensile test, see Tables 4, 5) shows a complete exchange of initial thermal stresses during plastic deformation. The changes in hydrostatic stresses are balanced over both phases, i.e. the mean stress for the Al/SiCp composite, weighted by the volume fractions of phases, is close to zero (cf. Eq. 3). It should be emphasised, that the hydrostatic stress seen by the diffraction experiment represents average value over many grains, although local stresses in the matrix are not of a purely hydrostatic nature. According to the EPSC model, the mean hydrostatic stresses did not change significantly after plastic deformation, while in the real composite important relaxation of these stresses was found. This phenomena can be explained by the evolution of heterogeneous stresses in the composite matrix and/or by the damage processes initiated in the interface between the ceramic reinforcement and the metal matrix.

On the basis of the lattice strain evolution in both measured Al/SiCp materials, it can be stated that the partitioning of the load between the Al2124 matrix and SiCp reinforcement is correctly predicted for elastic deformation. A good accordance between experiment and model lattice strains can be obtained also for advanced plastic deformation as well as after samples unloading, if the initial stresses are relaxed at small plastic deformation (Figs. 7, 8). The latter process is not reproduced by the original EPSC model and it must be introduced during calculations.

As shown in Fig. 8, in the elastic range of deformation the lattice strains measured using different hkl reflections are almost equal within each phase of the Al/SiCp-T6 composite but very different between phases. This result, confirmed by the EPSC model, can be explained through almost isotropic elastic properties of the Al and SiC crystallites and important difference between elastic constants of both phases (Table 2). During plastic deformation the differences between the lattice strains determined with different hkl reflections in the Al2124 matrix become significant (Fig. 8). This is an effect of intergranular stresses caused by anisotropy of plastic deformation occurring at the scale of Al grains. The lattice strain evolutions are correctly predicted in both measured directions for the unreinforced Al2124-T6 alloy (cf. \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) and \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{22} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) in Fig. 6) and in the direction perpendicular to the applied load for the Al2124-T6 matrix in the Al/SiCp composite (cf. \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{22} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) in Fig. 8a). However, some disagreement between model prediction and experiment is observed along the loading direction (cf. \(\left\langle {\varepsilon_{11} } \right\rangle_{{\left\{ {hkl} \right\}}}\) in Fig. 8a), probably due to stress heterogeneity in the matrix, which is not taken into account in model calculations. In the case of SiCp reinforcement, similar values of the lattice strains were found for different hkl reflections because this phase remains elastic during the whole deformation range (anisotropic plastic incompatibility stresses are not generated in the SiC particles).

It was also found, that the results of the diffraction experiment are consistent with the macroscopic results when they are interpreted by the EPSC model (Figs. 4, 5). Comparing the results for the Al2124-T6 alloy without reinforcement and this alloy in the Al/SiCp-T6 composite (both subjected to the same heat treatment), nearly the same plastic behaviour was found (i.e. the SiCp particles do not significantly influence dislocations movement in the matrix). On the other hand, the overall stresses for the composite are much higher than the stresses in the Al2124 alloy during the whole tensile test. This important increase of material strengthening is characteristic for composites and results mainly from the transfer of high stress to the reinforcement, while the von Mises stress in the matrix does not increase significantly above the yield value. The latter effect and its influence on overall composite properties were well predicted by the EPSC model (cf. Fig. 4b).

The comparison of Al/SiC-T1 and Al/SiC-T6 samples clearly shows the effect of heat treatment on the strengthening of the composite (Fig. 5). It is seen that the stresses localised both in the Al2124 matrix and SiCp reinforcement are higher in the case of the material subjected to the T6 treatment (Fig. 7). This effect can be explained due to the highest precipitation hardening of the Al2124-T6 matrix obtained by the latter treatment (the peak aged condition), while the hardening is much smaller for the same alloy subjected to the T1 treatment. Consequently, the matrix is harder after the T6 treatment in comparison with the T1 process, causing higher strengthening of the Al/SiCp-T6 composite, correctly predicted by EPSC model.

5 Conclusions

The diffraction method combined with crystallographic models are an important tool in the study of the mechanical behaviour of polycrystalline materials at the scale of phases or particular grains. In this work a complete study of the mechanical behaviour of the Al/SiCp composite containing 17.8% of SiC reinforcement with a grain size of 0.7 μm was performed using neutron diffraction and EPSC model. Based on the results of in situ measurements during the tensile test the following conclusions can be formulated:

-

1.

The thermal stresses relax during tensile deformation at the beginning of plastic strain and a new stress state is created.

-

2.

The strain/stress partitioning between the composite phases during the tensile test can be well predicted by the EPSC model, except for the thermal stress relaxation, which must be introduced into the model at the yield point.

-

3.

Anisotropy of plastic incompatibility stresses occurs during and after plastic deformation, both for the unreinforced and reinforced aluminium alloy and this effect is approximately predicted by EPSC model.

-

4.

Strengthening of the Al/SiCp composite results mainly from the transfer of high stress to the reinforcement, while the hardening of the matrix by the SiCp particles is insignificant.

-

5.

Using two different thermal treatments for the initial material, it was shown that the overall strength of the composite depends on the hardness of the Al2124 matrix, which can be increased through appropriate thermal treatment.

References

K.V.C. Amitesh, Aluminium based metal matrix composites for aerospace application: a literature review. IOSR J. Mech. Civ. Eng. 12, 31–36 (2015)

S.B. Prabu, L. Karunamoorthy, S. Kathiresan, B. Mohan, Influence of stirring speed and stirring time on distribution of particles in cast metal matrix composite. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 171, 268–273 (2006)

M.M. Boopathi, K.P. Arulshri, N. Iyandurai, Evaluation of mechanical properties of aluminium alloy 2024 reinforced with silicon carbide and fly ash hybrid metal matrix composites. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 10, 219–229 (2013)

M.R. Daymond, H.G. Priesmeyer, Elastic–plastic deformation of ferritic steel and cementite studied by neutron diffraction and self-consistent modeling. Acta Mater. 50, 1613–1623 (2002)

G. Garcés, K. Máthis, P. Pérez, J. Čapek, P. Adeva, Effect of reinforcing shape on twinning in extruded magnesium matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 666, 48–53 (2016)

N. Jia, Z.H. Cong, X. Sun, S. Cheng, Z.H. Nie, Y. Ren, P.K. Liaw, Y.D. Wang, An in situ high energy X-ray diffraction study of micromechanical behavior of multiple phases in advanced high-strength steels. Acta Mater. 57, 3965–3977 (2009)

A. Baczmański, C. Braham, Elastoplastic properties of duplex steel determined using neutron diffraction and self-consistent model. Acta Mater. 52, 1133–1142 (2004)

S. Cai, M.R. Daymond, R.A. Holt, Deformation of high β-phase fraction Zr–Nb alloys at room temperature. Acta Mater. 60, 3355–3369 (2012)

A. Baczmański, Y. Zhao, E. Gadalińska, L. Le Joncour, S. Wroński, C. Braham, B. Panicaud, M. François, T. Buslaps, K. Soloducha, Elastoplastic deformation and damage process in duplex stainless steels studied using synchrotron and neutron diffractions in comparison with a self-consistent model. Int. J. Plast. 81, 102–122 (2016)

C.J. Davidson, T.R. Finlayson, M.E. Fitzpatrick, J.R. Griffiths, E.C. Oliver, Q. Wang, Observations of the stress developed in Si inclusion following plastic flow in the matrix of an Al–Si–Mg alloy. Philos. Mag. 97, 1398–1417 (2017)

M.E. Fitzpatrick, P.J. Withers, A. Baczmański, M.T. Hutchings, R. Levy, M. Ceretti, A. Lodini, Changes in the misfit stresses in an Al/SiCp metal matrix composite under plastic strain. Acta Mater. 50, 1031–1040 (2002)

A.J. Allen, M.A.M. Bourke, S. Dawes, M.T. Hutchings, P.J. Withers, The analysis of internal strains measured by neutron diffraction in Al/SiC metal matrix composites. Acta Metall. Mater. 40, 2361–2373 (1992)

M. Dutta, G. Bruno, L. Edwards, M.E. Fitzpatrick, Neutron diffraction measurement of the internal stresses following heat treatment of a plastically deformed Al/SiC particulate metal–matrix composite. Acta Mater. 52, 3881–3888 (2004)

M.R. Daymond, M.E. Fitzpatrick, Effect of cyclic plasticity on internal stresses in a metal matrix composite. Metall. Mater. Trans. A 37, 1977–1986 (2006)

T.W. Clyne, P.J. Withers, An Introduction to Metal Matrix Composites, Cambridge Solid State Science Series (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1993)

J. Segurado, J. Llorca, A numerical approximation to the elastic properties of sphere-reinforced composites. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 50, 2107–2121 (2002)

J. Segurado, J. LLorca, A new three-dimensional interface finite element to simulate fracture in composites. Int. J. Solids Struct. 41, 2977–2993 (2004)

J.J. Williams, J. Segurado, J. LLorca, N. Chawla, Three dimensional (3D) microstructure-based modeling of interfacial decohesion in particle reinforced metal matrix composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 557, 113–118 (2012)

J.D. Eshelby, The determination of the elastic field of an ellipsoidal inclusion, and related problems. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. A 241, 376–396 (1957)

A. Roatta, R.E. Bolmaro, An Eshelby inclusion-based model for the study of stresses and plastic strain localization in metal matrix composites. I: general formulation and its application to round particles. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 229, 182–191 (1997)

C. Gonzalez, J. LLorca, A self-consistent approach to the elastic–plastic behavior of two-phase materials including damage. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 48, 675–692 (2000)

O. Pierard, C. Gonzalez, J. Segurado, J. LLorca, I. Doghri, Micromechanics of elastic–plastic materials reinforced with ellipsoidal inclusions. Int. J. Solids Struct. 44, 6945–6962 (2007)

M. Kursa, K. Kowalczyk-Gajewska, M.J. Lewandowski, H. Petryk, Elastic–plastic properties of metal matrix composites: validation of meanfield approaches. Eur. J. Mech. A Solids 68, 53–66 (2018)

A. Baczmański, R. Levy-Tubiana, M.E. Fitzpatrick, A. Lodini, Elastoplastic deformation of Al/SiCp metal-matrix composite studied by self-consistent modelling and neutron diffraction. Acta Mater. 52, 1565–1577 (2004)

G. Requena, D.C. Yubero, J. Corrochano, J. Repper, G. Garcés, Stress relaxation during thermal cycling of particle reinforced aluminium matrix composites. Compos. A 43, 1981–1988 (2012)

P. Fernandez-Castrillo, G. Bruno, G. Gonzalez-Doncel, Neutron and synchrotron radiation diffraction study of the matrix residual stress evolution with plastic deformation in aluminum alloys and composites. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 487, 26–32 (2008)

S. Cabeza, T. Mishurova, G. Bruno, G. Garcés, G. Requena, The role of reinforcement orientation on the damage evolution of AlSi12CuMgNi +15% Al2O3 under compression. Scr. Mater. 122, 115–118 (2016)

S. Cabeza, T. Mishurova, G. Garcés, I. Sevostianov, G. Requena, G. Bruno, Stress-induced damage evolution in cast AlSi12CuMgNi alloy with one- and two-ceramic. J. Mater. Sci. 52, 10198–10216 (2017)

M.E. Fitzpatrick, M.T. Hutchings, P.J. Withers, The determination of the profile of macrostress and thermal mismatch stress through an A1/SiCp composite plate from the average residual strains measured in each phase. Physica B 213–214, 790–792 (1995)

R. Levy-Tubiana, A. Baczmanski, A. Lodini, Relaxation of thermal mismatch stress due to plastic deformation in an Al/SiCp metal matrix composite. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 341, 74–86 (2003)

G. Bruno, M. Ceretti, E. Girardin, A. Giuliani, A. Manescu, Relaxation of residual stress in MMC after combined plastic deformation and heat treatment. Scr. Mater. 51, 999–1004 (2004)

M.E. Fitzpatrick, M. Dutta, L. Edwards, Determination by neutron diffraction of effect of plasticity on crack tip strains in a metal matrix composite. Mater. Sci. Technol. 14, 980–986 (1998)

L.F. Mondolfo, Aluminium Alloys: Structure and Properties (Butter Worths, London, 1976)

K. Walther, A. Frischbutter, Ch. Scheffzük, M. Korobshenko, F. Levchanovski, A. Kirillov, N. Astachova, S. Murashkevich, Epsilon-mds—a neutron time-of-flight diffractometer for strain measurements. Solid State Phenom. 105, 67–70 (2005)

A.M. Balagurov, G.D. Bokuchava, E.S. Kuzmin, A.V. Tamonov, V.V. Zhuk, Neutron RTOF diffractometer FSD for residual stress investigation. Z. Kristallogr. Suppl. Issue(23), 217–222 (2006)

P. Kot, A. Baczmański, E. Gadalińska, S. Wroński, M. Wroński, M. Wróbel, Ch. Scheffzük, G. Bokuchava, Neutron diffraction study of phase stresses evolution in Al/SiC composite during heat treatment and compression. Mech. Phy. Solids (in preparation for publication)

P. Lipinski, M. Berveiller, Elastic–plasticity of micro- inhomogeneous metals at large strains. Int. J. Plast. 5, 149–172 (1989)

P. Lipinski, M. Berveiller, E. Reubrez, J. Morreale, Transition theories of elastic–plastic deformation of metallic polycrystals. J. Arch. Appl. Mech. 65, 291–311 (1995)

L.L. Snead, T. Nozawa, Y. Katoh, T.-S. Byun, S. Kondo, D.A. Petti, Handbook of SiC properties for fuel performance modeling. J. Nucl. Mater. 371, 329–377 (2007)

G. Simmons, H. Wang, Crystal Elastic Constants and Calculated Aggregate Properties: A Handbook (The MIT Press, Cambridge, 1971)

ASM Handbook, Volume 2: Properties and Selection: Nonferrous Alloys and Special-Purpose Materials ASM Handbook Committee, Properties of Wrought Aluminum and Aluminum Alloys (ASM International, 1990), pp. 62–122

A. Baczmański, P. Lipinski, A. Tidu, K. Wierzbanowski, B. Pathiraj, Quantitative estimation of incompatibility stresses and elastic energy stored in ferritic steel. J. Appl. Cryst. 41(5), 854–867 (2008)

S. Wroński, A. Baczmański, R. Dakhlaoui, C. Braham, K. Wierzbanowski, E.C. Oliver, Determination of the stress field in textured duplex steel using the TOF neutron diffraction method. Acta Mater. 55, 6219–6233 (2007)

A. Baczmański, N. Hfaiedh, M. François, K. Wierzbanowski, Plastic incompatibility stresses and stored elastic energy in plastically deformed copper. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 501, 153–165 (2009)

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant from the Polish National Scientific Centre (NCN) No. UMO-2017/25/B/ST8/00134 and by the AGH UST statutory tasks No. 11.11.220.01/5 within a subsidy of the Ministry of Science and Higher Education. The authors wish to thank the Frank Laboratory of Neutron Physics (JINR Dubna, Russia) for providing the neutrons. The neutron experiments were supported by the Polish-JINR Programme 2017 (item 24), and the operation of the EPSILON diffractometer was supported by the Federal Ministry for Education and Research in Germany.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

OpenAccess This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Gadalińska, E., Baczmański, A., Wroński, S. et al. Neutron Diffraction Study of Phase Stresses in Al/SiCp Composite During Tensile Test. Met. Mater. Int. 25, 657–668 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12540-018-00218-7

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12540-018-00218-7