Abstract

Introduction

Despite the poor prognosis for adults with relapsed or refractory (RR) Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-negative B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL), long-term survival is possible and may even be considered as “cure”.

Methods

This study used a Delphi panel approach to explore concepts of cure in RR Ph-negative B cell precursor ALL. Ten European experts in this disease area participated in a survey and face-to-face panel meeting.

Results

Findings showed that clinicians conceptualize “cure” as a combination of three broad treatment outcomes that vary depending on the treatment stage: complete remission early in treatment (1–3 months) indicates initial success; eradicating cancer cells (minimal residual disease negative status) consolidates the early clinical response; leukemia-free survival is required in the long term.

Conclusions

Although such terminology remains contested, clinicians would begin considering “cure” as early as 2 years provided the patient is off therapy, with most considering the term applicable by the third year.

Funding

Amgen Inc.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The prognosis is poor for adults with Philadelphia chromosome (Ph)-negative B cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia (ALL) that is refractory to treatment or has relapsed. In this setting, more than 90% of patients die from the disease, typically within a few months of diagnosis [1,2,3,4].

There is no universally accepted treatment protocol for adults with relapsed or refractory (RR) Ph-negative B cell precursor ALL in Europe. Guidelines and recommendations for the treatment of adults with ALL generally do not recommend particular treatments specifically for patients with RR disease [1, 4,5,6,7,8,9]. The approach to treatment is thus heterogeneous, with a wide variety of therapies used and no clearly superior chemotherapeutic option. Currently, a common treatment option following complete remission achieved with chemotherapy is allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT), which may be offered as a curative approach. However, in the population with RR disease, even after HSCT, approximately 30% of patients may experience relapse [10].

Despite the poor prognosis in RR-ALL, long-term survival is possible and may even be considered as “cure”. Published guidance and descriptions of what constitutes cure can vary, and the term “cure” itself can be used in a number of ways regarding outcomes in oncology [11]. Treatment outcomes in clinical trials are often reported as median overall survival and/or progression- and response-related endpoints, but these metrics may not completely describe the full benefit of treatments that can lead to long-term survival or “cure” [11]. In a recent literature review of how different groups (such as clinicians, academics, patient groups, and payers) describe cure in oncology, Johnson and colleagues found that “cure” itself can be understood as three broad categories: lack of disease progression, eradication of cancerous cells, and long-term survival [11].

The disease setting of RR-ALL is particularly appropriate for exploring concepts of “cure” as a result of a number of factors. This disease is generally associated with a poor prognosis and substantial heterogeneity in treatment approaches. Furthermore, the rarity of the disease means that some concepts and definitions of “cure” and outcomes used in other areas of oncology, such as eradication of cancerous cells, are less well established. As such, the aim of this study was to investigate clinician perceptions of what constitutes successful treatment outcomes and “cure” for adults with RR-ALL.

Methods

Design

This study used a Delphi design to achieve consensus on perceptions of “cure” and treatment success in adult patients with RR-ALL. The Delphi approach uses a system of iterative questioning on an issue that leads to consensus [12]. The iterative process combines the benefits of obtaining insights from subject matter experts with the structure and detail of a survey. It has long been recognized that when a subject cannot be quantitatively determined or measured, the Delphi approach allows experts to contribute subjective assessments [13]. It is a well-accepted methodology that has been increasingly used in health care over time [13], where it is beneficial for a range of activities such as grappling with clinical problems and clinical guidelines, forecasting disease patterns and funding requirements [14], and gaining consensus on specific questions, such as establishing biomarkers in certain diseases [15]. Although the traditional Delphi technique uses a series of surveys to gain consensus, it is increasingly common to adapt the Delphi process by including a face-to-face meeting component while maintaining the essential Delphi features of consensus on a specific topic from a group of experts [15]. The face-to-face aspect allows more immediate discussion between panelists than would otherwise be possible with surveys.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

All participants agreed to complete the survey and attend the panel meeting, thereby consenting to participate in the project. The study and consent procedure were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Technology Sydney, Australia (reference number PRMA3477_2015_04).

Setting and Participants

International clinical experts with backgrounds in hemato-oncology were invited to join the study via email. The clinicians were invited on the basis of their background and were required to be board-certified or a specialist in clinical or medical oncology. Experience requirements included a minimum of 5 years in their role post-training and treating a minimum of 10 patients with ALL per year.

Data Collection

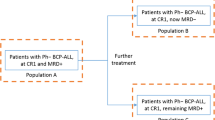

Data collection for the Delphi process in this study included two phases (Fig. 1). In phase 1, the clinicians completed an interactive PDF survey via email, comprising categorical, numerical, and open-ended questions that related to a clinician’s background, treatment practices, and definitions of relevant terms and concepts (Table 1). Phase 2 consisted of a face-to-face expert panel meeting with a survey component.

In recognition of the sometimes contested terminology of cure in relation to ALL, the adopted survey terminology was designed to be broad, to facilitate discussion among respondents. The survey used the following terminology to categorize cure: “complete remission”, “eradication of cancerous cells (i.e., molecular minimal residual disease (MRD) negative)”, and “prolongation of survival”. Although there was no established definition of “complete remission” specific to RR-ALL at the time of the study, the definition used in acute myeloid leukemia after the first line of treatment was adopted for this survey. This definition included a number of different aspects of remission, such as morphologic complete remission with incomplete blood count recovery, neutrophil count, molecular complete remission, and the absence of extramedullary leukemia (e.g., central nervous system or soft tissue involvement) [16]. The term “eradication of cancerous cells” was used in the survey with an explanatory note that it should be considered to refer to molecular MRD negativity, which indicates the lack of residual leukemic cells as determined by thresholds for conventional morphologic methods [17]. MRD is important in ALL because it can be evaluated in approximately 95% of patients with all types of this disease [17]. Although the panel responses in this study were specific to the definition “eradication of cancerous cells (molecular MRD negativity)”, it is acknowledged that MRD response must be durable, and that defining MRD itself can be complicated and open to dispute given the different technologies available with varying specificity and sensitivity [17,18,19].

Following the survey, individual responses were entered into a spreadsheet and anonymized. The analysis involved determining frequencies for descriptive (categorical) responses and reviewing qualitative data in preparation for the face-to-face meeting.

In phase 2, the question set featured in the phase 1 survey was not expected to change beyond the initial version; however, as a result of the nature of the Delphi technique, further questions which would benefit from a consensus vote during the panel meeting evolved through this process. At the face-to-face panel meeting, the aim was to achieve consensus on answers to the questions in the phase 1 survey and to address any new questions that were developed for phase 2. The panel was moderated by members of the research team experienced in the consensus technique, and involved presenting each question and a summary of anonymized responses from phase 1. The discussion around the responses sought to achieve consensus by collecting responses confidentially, with televoting “clickers”, that showed anonymized summaries of results immediately for live review.

In published Delphi studies, definitions of consensus vary widely from 50% to 100% [15]. In this study, consensus was defined as 80% agreement for categorical questions; numeric responses were displayed in pre-specified categorical ranges, and consensus was defined as responses within two consecutive ranges. Where no consensus was achieved after two rounds, and where discussion suggested further voting would not achieve consensus, this outcome was noted and no further iterations took place.

Results

Participants

Ten clinicians from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK participated in the survey and expert panel. Nine were hematologists and one was a hemato-oncologist. Most worked in the hospital setting (university hospitals, n = 8; community/urban/general hospital, n = 1), and one worked in a specialist hematology center.

Clinicians were asked about their patients in the clinic; trial patients were excluded. The clinicians had between 6 and 35 years of experience treating adults with RR-ALL. Before participating in the survey, clinicians answered a screening question to ensure they treated at least ten patients with ALL per year. In the survey, clinicians were asked how many patients they treated with specific subtypes of ALL. Survey responses showed that, in the preceding 12 months, clinicians had treated a mean of 14 patients with B cell precursor ALL (range 3–30), a mean of 9 patients with Ph-negative B cell precursor ALL (range 2–20), and a mean of 6 patients with RR-ALL (range 2–15).

Definitions of “Cure”

Clinicians agreed that three outcome elements of “cure” are important in ALL: complete remission, eradication of cancerous cells (i.e., molecular MRD negative), and prolongation of survival. The most common priority outcome (i.e., ranked first), according to those who responded to the question, was complete remission; eradication of cancer cells was frequently ranked second; and prolongation of survival was ranked third by four of the five clinicians who ranked all three options. Responses in phase 1 suggested that prolongation of survival may be a consequence of one (or both) of the other two outcomes (complete remission and eradication of cancerous cells). Responses relating to timing indicated that these three outcomes are not considered separately, and may be closely linked.

After further discussion at the panel meeting, clinicians agreed that aims of treatment changed with time, and that the outcomes were difficult to consider individually. Clinicians noted that in the 1–3 months following the start of treatment, complete remission is a key aim of therapy because it is the best indicator of response in this time frame (as it may not yet be possible to see or measure cell changes). After 3–6 months, clinicians look for the eradication of cancerous cells as reflected by persistent MRD negativity. Beyond 6 months, survival is the key outcome if the other two outcomes have been achieved (Fig. 2).

The curative outcomes are therefore considered as a package or stepwise approach. Survival is the prerequisite to measuring either complete remission or MRD negativity (the patient must be alive to measure complete remission and MRD status; physicians acknowledged the current lack of consensus around measuring MRD itself, in terms of heterogeneity of testing and the appropriate cutoff for determining negativity). Complete remission was agreed to be essential in keeping the patient alive.

Clinicians indicated that their treatment priorities change for their patients with disease that is particularly difficult to treat; such patients are more advanced along the treatment line and therefore the focus becomes eradicating cancerous cells, but no consensus was reached for the priority of curative outcomes for this subgroup.

HSCT

Clinicians also noted that a number of factors influence their decision to treat a patient with curative intent, including whether or not that patient was eligible for HSCT (Table 2). Clinicians were also asked for their opinion about the role of HSCT in cure, specifically, whether a patient should only be considered “cured” if the patient has undergone HSCT or is eligible for HSCT. There was consensus that HSCT is an essential step on the treatment pathway (80% agreed that HSCT is an essential step on the pathway to cure), but not that HSCT necessarily determines cure. A patient may be considered cured without HSCT when reaching the stated time points in complete remission without relapse. However, it was also noted by clinicians that the proportion of patients who may be cured without HSCT is extremely small with currently available chemotherapy treatments. For most other HSCT-eligible patients, transplant is currently considered the best therapy option for achieving cure after complete remission is achieved.

Timing of “Cure”

All clinicians who responded in the survey stated that a patient could be considered to be cured from either 3 or 5 years from the start of salvage therapy; however, some comments from the survey suggested that “cure” may be possible after 2 years. These time frames were not dependent on how clinicians defined cure (complete remission, eradication of cancerous cells, or prolongation of survival). In the phase 2 voting, the consensus was that “cure” would be considered at 2–3 years, since the combination of these two consecutive responses exceeds the 80% threshold for consensus (Table 3); one further clinician noted that cure would be established at 5 years.

Clinicians noted that if they consider the survival curve for the overall natural history of the disease, the curve flattens from around 3 years, which aligns with the time frame for thinking of cure; some clinicians felt that they might start to think a patient may be cured after 2 years, but do not say so with complete confidence until after 5 years.

This approach to the timing of “cure” did not vary between patient populations (overall population versus patients with disease that is particularly difficult to treat).

Rates of “Cure”

Clinicians were asked to estimate the percentage of their patients (in their current caseload) whom they considered to be treated with curative intent. When estimating this, clinicians reported in the phase 1 surveys that between zero and 40% of patients might be considered “cured”; no consensus was reached in the face-to-face panel, and the panelists noted that the original upper limit of the range of 40% was somewhat high for patients seen in clinical practice.

Responses to the clinician survey suggested that no more than 10% of patients with particularly difficult-to-treat disease would be considered cured, but no consensus was reached by the panel on the percentage range for these patients. Clinicians noted that 10% is a realistic upper limit of the range of patients who can be considered cured.

Discussion

This study shows that clinicians conceptualize “cure” as a combination of three key treatment outcomes for patients being treated for RR-ALL: complete remission, eradication of cancerous cells (i.e., prolonged molecular MRD negativity), and prolonged survival. Moreover, they see these outcomes as interlinked, with prolongation of survival as a consequence of one (or both) of the other two outcomes. The consensus was that “cure” would be considered at 2–3 years (80% of the respondents selected these two consecutive time periods). Clinicians noted that if they consider the survival curve for the overall natural history of the disease, the curve flattens from around 3 years, aligning with the time frame for thinking of cure. The published literature also suggests that many patients who survive for 2 years will also reach 3-year survival, with studies indicating that survival curves for patients with MRD negative status generally begin to plateau from around the 2-year mark [20, 21].

Although “cure” is understood to comprise complete remission, eradication of cancerous cells, and prolonged survival, the particular clinical focus on each element changes over time. As the findings show, early in treatment (1–3 months), clinicians look for complete remission to indicate initial success; eradicating cancer cells (achieving MRD negative status) and maintaining this status will then strengthen clinicians’ view of the initial success. Finally, after treatment is completed, if the patient continues to remain MRD negative over a prolonged period of time, then clinicians begin to consider cure.

In theory, HSCT is not necessary for patients to be considered cured, although complete remission and MRD negative status may make patients better candidates for HSCT, if eligible. However, although it is possible for patients to achieve “cure” without having received HSCT, it is very rare for this to be the case with currently available chemotherapy treatments. This may change as new treatment options become more widely available, but historically, HSCT has been considered the best option for achieving “cure” for those patients eligible for the treatment. The published literature shows that the majority of patients with long survival have received HSCT, while other factors also play a part in survival, such as a younger age, time to complete remission, duration of complete response, and late relapse [3, 22,23,24,25]. Some clinicians would start to consider “cure” as early as 2 years in this setting, with the consensus being that “cure” would be considered by the third year. It is important that these findings are understood in the context of treatment: these time frames may be considered for “cure” but only if the patient is no longer receiving treatment; that is, a patient must have ceased therapy at these time points for them to be considered in any way “cured”.

It should also be emphasized that the terminology used to conceptualize “cure” and outcomes, and specifically the term “eradication of cancerous cells”, is yet to be fully established in this particular disease setting. Thus, although the broad categories of cure described by Johnson and colleagues [11] are useful as starting points for discussions of “cure” in cancer, a degree of caution is needed in interpreting these findings, as intrapractice definitions of MRD and thresholds for MRD negativity can be unclear, given the different techniques available and their respective advantages and disadvantages [18, 19].

This study had several strengths and limitations. The findings contribute knowledge to an under-researched area; using the Delphi technique to generate this knowledge is a further strength, because this is an established method to elicit critical thinking on complex issues from a group of experts who may be geographically scattered [13], and it is an appropriate choice for an area such as this, where there is little published evidence or consensus available [14]. As with all studies, there are some limitations. Although the panel involved expert members in the field, potential limitations of the Delphi approach include the comparatively small sample of experts. However, given the rarity of the disease, there are relatively fewer experts in this field than in other disease areas. Additionally, the experts included in the study were from France, Germany, Italy, Spain, and the UK, and thus the findings may not be generalizable in other geographical regions and oncological contexts outside the scope of this study. This study also modified the traditional Delphi approach by using a face-to-face expert panel in the second phase, rather than a further survey; therefore, it was not possible to maintain anonymity for the participants, nor to avoid the potential for group dynamics to play a role in establishing a consensus for a given item [12]. However, the electronic “clickers” ensured individual responses were unknown to others within the panel, and anonymity in their responses was maintained [14, 15].

Future research could examine perceptions of “cure” in other settings, and extend this research to involve more clinicians across countries. A registry and database study could also be established to verify these results, particularly in the context of new treatments that may affect perceptions of “cure” in the future.

Conclusions

This study shows that clinicians do have a concept of “cure” when treating patients for RR-ALL. Although exact definitions may vary, and the terminology may remain contested, there is agreement that clinicians could consider patients cured after a period of 2 years off therapy, and most agreed that a patient would be considered cured after a third year.

References

Bassan R, Hoelzer D. Modern therapy of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(5):532–43.

Forman SJ, Rowe JM. The myth of the second remission of acute leukemia in the adult. Blood. 2013;121(7):1077–82.

Oriol A, Vives S, Hernandez-Rivas JM, et al. Outcome after relapse of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adult patients included in four consecutive risk-adapted trials by the PETHEMA Study Group. Haematologica. 2010;95(4):589–96.

Kantarjian HM, Thomas D, Ravandi F, et al. Defining the course and prognosis of adults with acute lymphocytic leukemia in first salvage after induction failure or short first remission duration. Cancer. 2010;116(24):5568–74.

Gokbuget N, Hoelzer D, Arnold R, et al. Treatment of adult ALL according to protocols of the German Multicenter Study Group for Adult ALL (GMALL). Hematol Oncol Clin N Am. 2000;14(6):1307–25.

Huguet F, Leguay T, Raffoux E, et al. Pediatric-inspired therapy in adults with Philadelphia chromosome-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia: the GRAALL-2003 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27(6):911–8.

Faderl S, O’Brien S, Pui C, et al. Adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer. 2010;116(5):1165–76.

Brandwein JM. Treatment of acute lymphoblastic leukemia in adolescents and young adults. Curr Oncol Rep. 2011;13(5):371–8.

Hoelzer D, Bassan R, Dombret H, Fielding A, Ribera JM, Buske C. Acute lymphoblastic leukaemia in adult patients: ESMO Clinical Practice Guidelines for diagnosis, treatment and follow-up. Ann Oncol. 2016;27(suppl 5):v69–82.

Poon LM, Hamdi A, Saliba R, et al. Outcomes of adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia relapsing after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transpl. 2013;19(7):1059–64.

Johnson P, Greiner W, Al-Dakkak I, Wagner S. Which metrics are appropriate to describe the value of new cancer therapies? BioMed Res Int. 2015;2015:865101.

Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12(10):1–8.

Linstone HA, Turoff M. Introduction. In: Linstone HA, Turoff M, editors. The Delphi method: techniques and applications. 2002 ed. MA: Addison-Wesley; 1975.

Thangaratinam S, Redman CW. The Delphi technique. Obstet Gynaecol. 2005;7(2):120–5.

Oberg K, Modlin IM, De HW, et al. Consensus on biomarkers for neuroendocrine tumour disease. Lancet Oncol. 2015;16(9):e435–46.

Cheson BD, Bennett JM, Kopecky KJ, et al. Revised recommendations of the International Working Group for Diagnosis, Standardization of Response Criteria, Treatment Outcomes, and Reporting Standards for Therapeutic Trials in Acute Myeloid Leukemia. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21(24):4642–9.

Hoelzer D. Personalized medicine in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Haematologica. 2015;100(7):855–8.

van Dongen JJ, van der Velden VH, Bruggemann M, Orfao A. Minimal residual disease diagnostics in acute lymphoblastic leukemia: need for sensitive, fast, and standardized technologies. Blood. 2015;125(26):3996–4009.

Bassan R, Spinelli O. Minimal residual disease monitoring in adult ALL to determine therapy. Curr Hematol Malig Rep. 2015;10(2):86–95.

Dhedin N, Huynh A, Maury S, et al. Role of allogeneic stem cell transplantation in adult patients with Ph-negative acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2015;125(16):2486–96 (quiz 2586).

Salah-Eldin M, Abousamra NK, Azzam H. Clinical significance of minimal residual disease in young adults with standard-risk/Ph-negative precursor B-acute lymphoblastic leukemia: results of prospective study. Med Oncol. 2014;31(5):938.

Gokbuget N, Stanze D, Beck J, et al. Outcome of relapsed adult lymphoblastic leukemia depends on response to salvage chemotherapy, prognostic factors, and performance of stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2012;120(10):2032–41.

Thomas DA, Kantarjian H, Smith TL, et al. Primary refractory and relapsed adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia: characteristics, treatment results, and prognosis with salvage therapy. Cancer. 1999;86(7):1216–30.

Tavernier E, Boiron JM, Huguet F, et al. Outcome of treatment after first relapse in adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia initially treated by the LALA-94 trial. Leukemia. 2007;21(9):1907–14.

Thomas X, Le QH. Prognostic factors in adult acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Hematology. 2003;8(4):233–42.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the study. Massimiliano Bonifacio, Gesine Bug, Bella Patel, Arnaud Pigneux, and Josep-Maria Ribera also participated in the survey and panel. Deborah Saltman assisted in the study design.

Funding

This study, article processing charges and open access fees paid to the journal were funded by Amgen Inc. All authors had full access to all of the data in this study and take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis.

Medical Writing and/or Editorial Assistance

Medical writing and editorial assistance was provided by Roslyn Weaver and Max Pruetzel-Thomas of PRMA Consulting Ltd and funded by Amgen Inc.

Authorship

All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) criteria for authorship for this article, take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole, and have given their approval for this version to be published.

Authors’ contributions

JM and AK designed the study with input from AB and BB. JM and AK collected the data, including that provided by RB, DH, XT, PM, and JP. All authors (RB, DH, XT, PM, JP, KM, AK, AB, BB, and ZC) contributed to interpretation and analysis of the data and revision of the manuscript, and read and approved the final manuscript.

Disclosures

At the time of the study Arie Barlev was an employee of and held stock in Amgen Inc. Arie Barlev is currently an employee of Atara Biotherapeutics Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA. At the time of the study Beth Barber was an employee of and held stock in Amgen Inc. Beth Barber is currently an employee of Johnson & Johnson, Titusville, NJ, USA. At the time of the study Ze Cong was an employee of and held stock in Amgen Inc. Ze Cong is currently an employee of Global Blood Therapeutics, South San Francisco, CA, USA. Jan McKendrick is currently a Visiting Fellow at the University of Technology Sydney, New South Wales, Australia as well as being an employee of PRMA Consulting. Amber Kudlac was an employee of PRMA Consulting Ltd. Amber Kudlac is currently an employee of Vitaccess, Oxford, UK. Renato Bassan received personal fees from PRMA Consulting Ltd during the study, and has received personal fees from Amgen, Arian, and Pfizer outside the submitted work. Dieter Hoelzer, Jiri Pavlu, Pau Montesinos and Xavier Thomas have nothing to disclose.

Compliance with Ethical Guidelines

All participants agreed to complete the survey and attend the panel meeting, thereby consenting to participate in the project. The study and consent procedure were approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Technology Sydney, Australia (reference number PRMA3477_2015_04).

Data Availability

The questionnaire that study participants were asked to complete before the Delphi panel has been provided in a supplementary file. Sharing of individual responses is not appropriate as the Delphi process is anonymous and focuses on generating consensus, rather than collecting data.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Enhanced Digital Features

To view enhanced digital features for this article go to https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.7713515.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Bassan, R., Hoelzer, D., Thomas, X. et al. Clinician Concepts of Cure in Adult Relapsed and Refractory Philadelphia-Negative B Cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Delphi Study. Adv Ther 36, 870–879 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00910-z

Received:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12325-019-00910-z