Abstract

Since women were given the right to vote in the first half of the twentieth century, several studies verify the existence of noticeable differences in women and men voting conduct. Theories explaining such behavior rely mainly on stereotypes, differences in values as well as disparities in self-perceptions of men and women. This paper, using a unique and unusual gender-segregated voting booths that was in use in Argentina until 2007, suggests that labor market incentives play a key role explaining the electoral gender gap. Our estimations, which come out from a panel data of five presidential elections at district level, show that the voting gender gap reduces as women acquire the head of household status. That is, as women face analogous incentives to men, their evaluation of the incumbent performance and their policies tend to be similar to males leading to a reduction in the gender gap.

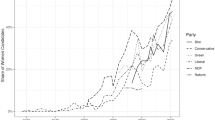

Source: own calculations based on data from Dirección Nacional Electoral. Vertical axe is expressed in percentages and horizontal axe is Presidential Election year. Due to missing data, boxes were computed using 24 districts for 1983; 20 districts for 1989 and 1995; 18 districts for 2003 and 17 districts for 1999 and 20 for 2007

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

As stated by Inglehart and Norris (2000) gender gap is a multidimensional political phenomenon that can refer to any political differences between women and men, such as mass participation, differences in voting selections and in political party sympathy as well as in political and ideological matters (see also Conover 1988). In this paper we just focus on voting behavior.

From the very first election that women participate in 1951, there were different polling places for men and women (Bercoff 2019).

The obligation to vote is waived for those citizens that are 500 km outside their legal residence. The amount of the fines to those citizens that fail to cast their vote are very low as well as the probability of being fined at all.

Positive Votes are obtained by subtracting blank and spoiled ballots from Total Votes.

Río Negro accounts for 1.4% of the total register voters. We also have missing data in two elections for the province of San Luis and in one election for the provinces of Chubut, Formosa, Salta and Tierra del Fuego.

According to INDEC, the status of Head of Household is granted by the rest of the persons living in the house, and there is only one head per household.

Researchers attribute the steady increase in the percentage of households headed by women to the breakup of the traditional family, including the rise in cohabitation, divorce and separation, non-marital childbearing, and lone motherhood (Liu et al. 2017). In addition, the decline in living standards and male wages associated to the economic contraction of the 1980s may have also contributed to the formation female headship (United Nations 1991).

Members of the Chamber of Deputies are elected on closed party lists from multi-member electoral districts (the provinces) using proportional representation, with the entire Chamber renewing by halves (one-half of the province’s legislative delegation) every two years.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this placebo test.

We thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting us this specification as robustness check.

References

Abrams BA, Settle RF (1999) Women’s suffrage and the growth of the welfare state. Public Choice 100:289–300

Aidt T, Dallal B (2008) Female voting power: the contribution of women’s suffrage to the growth of social spending in Western Europe (1869–1960). Public Choice 134:391–417

Aidt T, Dutta J, Loukoianova E (2006) Democracy comes to Europe: franchise extension and fiscal outcomes 1830–1938. Eur Econ Rev 50:249–283

Alesina A, La Ferrara E (2005) Preferences for redistribution in the land of opportunities. J Public Econ 89:897–931

Berbecel D (2019) Hyperpresidentialism in the Southern Cone of Latin America: examining the diverging cases of Argentina and Chile. PhD Dissertation, Politics Department, Princeton University

Bercoff J (2019) Who voted for Perón? Essays on the Argentine mid-20th century presidential elections. PhD Thesis. Universidad Carlos III

Blaydes L (2011) Elections and distributive politics in Mubarak´s Egypt. Cambridge University Press

Blaydes L, Linzer D (2014) The political economy of women´s support for fundamentalist Islam. World Politics 60(4):576–609

Bravo-Ortega C, Eterovic N, Paredes V (2018) What do women want? Female suffrage and the size of government. Econ Syst 42(1):132–150

Brians C (2005) Women for women? Gender and party bias in voting for female candidates. Am Politics Res 33(3):357–375

Campbell R (2016) Representing women voters: the role of the gender gap and the response of political parties. Party Politics 22(5):587–597

Carruthers C, Wanamaker M (2015) Municipal housekeeping: the impact of women´s suffrage on public education. NBER Working Paper #20864

Clarke H, Stewart M, Ault M, Elliott E (2005) Men, women, and the dynamics of presidential approval. Br J Political Sci 35(1):31–51

Clots- Figueras I (2010) Women in politics. Evidence from the Indian states. J Public Econ 95:664–690

Conover P (1988) Feminists and the gender gap. J Politics 50(4):985–1010

de Bromhead A (2018) Women voters and trade protectionism in the interwar years. Oxf Econ Pap 70(1):22–46

Deaux K (1985) Sex and gender. Annu Rev Psychol 36:49–81

Desposato S, Norrander B (2009) The gender gap in Latin America: contextual and individual influences on gender and political participation. Br J Political Sci 39(1):141–162

Dolan K (2008) Is there a “gender affinity effect” in American politics? Information, affect, and candidate sex in US House elections. Political Res Q 61(1):79–89

Eisenberg D, Ketcham J (2004) Economic voting in US presidential elections: who blames whom for what. Top Econ Anal Policy 4(1):19

Erickson L, O’Neil B (2002) The gender gap and the changing woman voter in Canada. Int Political Sci Rev 23(4):373–392

Fox R (1997) Gender dynamics in congressional elections. SAGE publications, London, UK

Funk P, Gathmann C (2006) What women want: suffrage, female voter preferences and the scope of government. Stanford University Center for International Development, p 285

Giger N (2009) Towards a modern gender gap in Europe? A comparative analysis of voting behavior in 12 countries. Soc Sci J 46:474–492

Givens T (2004) The radical right gender gap. Comp Pol Stud 37(1):30–54

Inglehart R, Norris P (2000) The developmental theory of gender gap: women’s and men’s voting behavior in global perspective. Int Polit Sci Rev 21(4):441–463

Jianakoplos N, Bernasek A (1998) Are women more risk averse? Econ Inq 36:620–630

Jones M, Meloni O, Tommasi M (2012) Voters as Fiscal Liberals. Incentives and accountability in federal systems. Econ Politics 24(2):135–156

Kam C (2009) Gender and economic voting, revisited. Elect Stud 28:615–624

Karp J, Brockington D (2005) Social desirability and response validity: a comparative analysis of overreporting voter turnout in five countries. J Politics 67(3):825–840

Kaufmann K (2006) The gender gap. Political Sci Politics 39:447–453

Köppl-Turyna M (2020) Gender gap in voting: evidence from actual ballots. Agenda Austria Working Paper 18

Krogstrup S, Wälti S (2011) Women and budget deficits. Scand J Econ 113(3):712–728

Lewis P (1971) The female vote in Argentina 1958–1965. Comp Pol Stud 3:425–441

Lewis P (2004) The Gender Gap in Chile. J Lat Am Stud 36(4):719–742

Lewis-Beck M, Paldam M (2000) Economic voting: an introduction. Elect Stud 19:113–121

Liu C, Esteve A, Treviño R (2017) Female-headed households and living conditions in Latin America. World Dev 90:311–328

Lott J, Kenny L (1999) Did women’s suffrage change the size and scope of government? J Polit Econ 107(6):1163–1198

McDermott M (1997) Voting cues in low-information elections: candidate gender as a social information variable in contemporary United States elections. Am J Political Sci 41(1):270–283

Montgomery R, Stuart C (1999) Sex and fiscal desire. Department of Economics, UCSB Working Paper

Panzer J, Paredes R (1991) The role of economic issues in elections. The case of the 1988 Chilean presidential referendum. Public Choice 71:51–59

Stark O, Zawojska E (2015) Gender differentiation in risk-taking behavior: on the relative risk aversion of single men and single women. Econ Lett 137:83–87

Strom M (2014) How husbands and wives vote. Elect Stud 35:215–229

Sunden A, Surette B (1998) Gender differences in the allocation of assets in retirement savings plans. Am Econ Rev 88(2):207–211

United Nations (1991) The vulnerability of household headed by women: policy questions and options for Latin America and the Caribbean. Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean LC/LC11. Santiago de Chile

Welch S, Hibbing J (1992) Financial conditions, gender and voting in American national elections. J Politics 54:197–213

Acknowledgements

We thank Julio Elias and participants of the Regional Science Association International Meeting (SAER) and Argentine Economic Association Meeting (AAEP) for comments and suggestions to earlier version of this paper and to Laia Kaliman, Franco Domínguez Paredes and Agostina Zulli for their research assistance. All remaining errors are ours.

Funding

This work was supported by the Secretaría de Ciencia, Arte e Innovación Tecnológica de la Universidad Nacional de Tucumán, Argentina (CIUNT) Grant PIUNT 26/F 612.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

José J. Bercoff and Osvaldo Meloni wrote and reviewed the whole manuscript text.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors report there are no competing interests that are relevant to the content of this article.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bercoff, J.J., Meloni, O. Looking inside the ballot box: gender gaps in Argentine presidential elections. Int Rev Econ 70, 237–255 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-023-00417-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12232-023-00417-8