Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic created a host of difficulties for college students. There is research noting the unique vulnerability of this population’s DASS symptoms and further connections of coping strategies. The current study aims to provide a snapshot of this unique time in higher education by examining the relationship between perceived difficulty, retrospectively, in the Spring 2020 semester and DASS symptoms in the Fall 2020 semester, and moderators of coping strategies in a sample of USA university students (n = 248; Mage = 21.08, SD = 4.63; 79.3% = Female). The results yielded a clear predictor relationship between perceived difficulty and symptoms of DASS. However, only problem-solving coping strategy proved a significant moderator for stress; surprisingly, problem-solving coping appeared to exacerbate the relationship. Implications for clinicians and higher education are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

The COVID-19 pandemic presented several obstacles for society at large. Major health outbreaks, such as pandemics, are known to have both physical and psychological impacts on individuals regardless of contracting a disease (Luo et al., 2021; Mak et al., 2009; Ren et al., 2021; Xiao et al., 2020). In particular, scholars anticipate mental health impacts that would be pervasive and widespread (Galea et al., 2020; Park et al., 2021). Adjustment related symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and stress, are of particular concern (Kibbey et al., 2021; Pappa et al., 2020; Park et al., 2021), and how one responds to and experiences stress prior to the pandemic was already of concern (Bell et al., 2017; Othman et al., 2019; Starcke & Brand, 2016). Thus, the cumulative impact of stressors during the pandemic (Di Renzo et al., 2020; Hamzah et al., 2019; Kramer & Kramer, 2020; López-Castro et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021; Xia et al., 2021) warrant investigation.

The abrupt shift to online learning in Spring 2020

As cases of COVID-19 rose in early 2020 and the World Health Organization (WHO) declared COVID-19 a global pandemic (Islam et al., 2020), Universities across the globe subsequently transitioned to online learning, creating a disruption in various domains of higher education, including social, academic, and business settings (López-Castro et al., 2021; Samuels et al., 2021). Online students have been reported to feel lonely and out of touch with academic learning (Rovai & Wighting, 2005). One report suggests that more than a quarter of the worldwide learner population are enrolled in at least one online course (DAAD, 2020; El Said, 2021). Another study has shown that higher feelings of belongingness were related to lower levels of stress related to the pandemic, and higher levels of pandemic-related stress were associated with lower academic motivation in a sample of undergraduate (Marler et al., 2021). Further, it is important to emphasize that students with no interest with online learning in the past, had to switch to an online learning setting regardless of their preference. As such, it is fair to infer the online shift was at least frustrating to many students.

It is important to emphasize that this framework is not to advise against online learning. In fact, several studies report little to no difference in grade performance of students in online vs. in-person course modalities (Cavanaugh & Stephen, 2015; El Said, 2021; Lorenzo-Alvarez, et al., 2019 Soesmanto & Bonner, 2019; Tan, 2019). However, a quick shift to an online format presents a different scenario. For example, Nyer (2019) conducted a study, prior to the pandemic, at a university in California to see effective ways of quickly offering online components to a traditional face-to-face course. The study revealed that there was lower engagement in the course when materials were quickly created, leaving some inferences to the importance of quality course instruction in an online setting. In another study, at the onset of the pandemic (Bozkurt et al., 2020), educational settings across multiple countries reported difficulties related to digital access, alternative methods of evaluation, and difficulty with the sudden online switch. Further, similar barriers were reported for mental health resources provided by universities (Folk et al., 2022), which suggest a potential increase in mental health difficulties, in particular mental health symptoms.

Adjustment symptoms among college students

Symptoms of adjustment refer to distress related to life events that can manifest as emotional disturbance (e.g., anxiety or depressed mood), but not necessarily to the point of clinical diagnosis (American Psychiatric Association, 2022; Reichenberg & Seligman, 2016). These symptoms can include stress, anxiety, and depression (Park et al., 2021). University students are already in a stage of transition developmentally and socially. Moving to a new, sometimes unfamiliar location, learning the new expectations in a post-secondary educational setting, and navigating new social relationships can be stressful (Garriott & Nisle, 2018; Hamzah et al., 2019; Kulig & Persky, 2017; Peleg et al., 2016). Further, it is not unheard of for college students to experience depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms (Broglia et al., 2017; Hamzah et al., 2019; Mustaffa et al., 2014; Zivin et al., 2009). In fact, Zivin et al. (2009) reported persistent stress and mental health struggles across two years in a sample of college students in a longitudinal analysis, concluding that a large number of individuals are aware of their struggles, but do not receive treatment. This emphasizes the need for emphasizing sources of stress and implementing early intervention.

Age and gender also appear to be a specific indicator to distress for some individuals (AlHadi et al., 2021; Bell et al., 2017; Kibbey et al., 2021; López-Castro et al., 2021; Park et al., 2021). Park et al. (2021) suggested that younger individuals, and women, might be more vulnerable to symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress in the context of the pandemic. Kibbey et al. (2021) also reported that vulnerability of college students and the compounding impacts from the pandemic that could occur in their unique life situation (e.g., displacement from the university, social network removal, abrupt and uncertain changes in their academic environment). Although, Islam et al. (2020) only saw this vulnerability among female participants but found the opposite with regard to age. López-Castro et al. (2021) found pandemic related stressors to be related to greater levels of poor mental health, particularly among females which makes up the majority of the current study’s sample of New York City college students.

These symptoms of adjustment have a renewed focus in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly at the beginning of lockdowns. Arënliu et al. (2021) noted pandemic related stressors including knowing someone infected, worries of financial fall out from various shutdowns, and overload of pandemic related information, were significant predictors of anxiety and depression in a sample of 904 university students in Kosovo. This was also the case in other studies conducted at this time (Elmer et al., 2020; Odriozola-González, et al., 2020; Passavanti et al., 2021; Ren et al., 2021; Serafim et al., 2021), establishing a pattern of pandemic related stress, particularly among university students. Further, the American Psychological Association (2020) released a statement reporting potential generational specific amplification of distress during the pandemic among young adults. There is also evidence suggesting the pandemic to exacerbate psychological distress (Marler et al., 2021). A daily diary study conducted during the onset of the pandemic (Xia et al., 2021), the association between daily stressors related to COVID-19 and emotional variability (i.e., shifts between positive and negative emotional states) was greater when the stress was greater. Thus, there is a clear need for comprehensive studies on the unique impacts the pandemic has had on the college student population.

Coping strategies and stress

Indeed, research has demonstrated the relations between coping strategies and stress and the current literature points to positive psychological outcomes especially when active coping strategies (e.g., approach oriented using cognition and behavior; Choi et al., 2012) are utilized (AlHadi et al., 2021; Eisenbarth, 2012; Folkman, 2008; Kavčič et al., 2022). The transactional stress or coping model (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) notion that how we are affected by distress is dependent on our overall resources such as coping strategies and psychosocial protections (Aldwin, 2007; Park et al., 2008, 2021) supports this. Thus, perhaps it is that stress is lesser among those with greater coping skill sets. This was supported in a latent profile analysis study of Slovenian adults (Kavčič et al., 2022). Specifically, depression anxiety and stress was the lowest among participants who were actively engaged in active rather than passive coping (e.g., indirect attempts to reduce or avoid a stressful situation; Choi et al., 2012). In a study of Chinese university students during the pandemic, Huang et al. (2021) found active coping to be associated with lower depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, which contrasted with passive coping which was associated with higher depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Another example of this can be found in Vintila et al. (2022) which found maladaptive strategies to positively mediate the relationship between health anxiety and COVID-19 anxiety. Taken together, perhaps style of coping can have a robust protection or risk during times of stress in multiple scenarios and contexts.

The current study

Indeed, Kavčič et al. (2022) answers many questions with regard to coping strategies and adjustment. However, the researchers make a point in their interpretations to emphasize the contextual and circumstantial nature of their results. While their results do address a snapshot in the time of the pandemic onset while measuring stress and coping strategies in adults, their results are not capturing the important factor of college student experiences. This is what the current study aims to do. To the author’s knowledge, it does not appear that the relationship between how college students’ perception of the abrupt change to online learning in the middle of the semester in Spring 2020 related to adjustment symptoms like stress, anxiety, and depression and how this differed based on coping strategies. The current study aims to add to this void in the literature and in turn provide insight to academics and clinicians. The following research questions and hypotheses are proposed:

-

RQ-1: How does the retrospective perceived difficulty during the Spring 2020 semester relate to depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms?

-

RQ-1 Hypothesis: Given that the literature supports the COVID-19 pandemic as a pervasive stressor, it is expected that stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms will be predicted significantly by student’s perception difficulty during the transition to online in the Spring 2020 semester.

-

-

RQ-2: How do the relations between retrospective perceived difficulty of the Spring 2020 transition and depression, anxiety, stress symptoms differ based on coping strategies of the participants?

-

RQ-2 Hypothesis: Based on the current literature and Lazarus and Folkman’s (1984) theory, it is expected that active coping strategies (e.g., problem solving and affective), will yield a significant moderation of the relationship between perceived difficulty and depression, anxiety, stress symptoms, more so than avoidant or passive strategies (e.g., fantasy, minimization of threat, and existential growth coping).

-

Transparency and openness

Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval was obtained for data examined in this manuscript. This study involved secondary analysis of existing data that the author felt answered the target research question. While the data are not pre-registered or available to the public, a data codebook can be provided upon request to the corresponding author.

Method

Procedures and participants

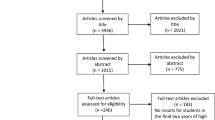

The study utilizes data from a larger study (Student Experiences Amid COVID-19 Project) conducted at a large public University in the District of Columbia, Maryland, and Virginia (DMV) region in the Fall 2020 semester. The Project aimed to examine college student well-being and mental health in the context of the immediate semesters surrounding the COVID-19 Pandemic. The data were collected via self-report survey in SONA systems which is open to all students at the institution. Some courses, particularly introductory psychology, require student participation in SONA studies. The survey took participants approximately 15–25 min to respond. Data cleaning commenced before analyses, including withdrawing inconsistent responses to control questions that indicated dishonesty.

Study participants (n = 248) were university students in a large public university in the DMV region of the Eastern United States who were enrolled in a course during the Spring and Fall semesters of the year 2020. On average, participants were age 21 (SD = 4.63) and predominantly reported their biological sex as female (79.3%). Reported gender identity of the participants indicated that the sample was fully cis-gendered. Participants were also racially diverse and predominantly living with family and disclosed “student only” as their employment status. Table 1 summarizes this information.

Measures

Perceived difficulty in Spring 2020

Items were composed for study participants to retrospectively self-report difficulty with access to course materials, ease of transition, and overall stress in the Spring 2020 semester when the major shift to online occurred. “Perceived Difficulty in Spring 2020” variable (α = 0.675). Items were significantly, positively correlated (r < .4; p > .001). For the item asking, “How difficult was it for you to access course materials required for success after the transition to online during the 2020 semester?” participants answered along a scale of 1 (Much more difficult than expected) to 5 (Much easier than expected). This item was reverse coded for data analysis so that higher values reflected greater difficulty, as was the next time asking, “How would you rate the overall ease of transition from face-to-face to online during the Spring 2020 Semester?” participants answered along a scale of 1 (extremely poor and difficult transition) to 6 (Extremely pleasant and seamless transition). Finally, for the item “How would you rate your stress during the Spring 2020 semester after the transition to online?” participants answered along a scale of 1 (very little stress, if at all) to 6 (Extremely Stressful). The mean score of the 3 items was calculated, after reverse coding one of them, to create the final variable. The finalized construct for this variable is for higher scores to indicate higher perceived stress, and lower scores to indicate lower perceived stress.

Coping strategies

The Coping Strategies Inventory (CSI, Quayhagen & Quayhagen, 1982) was utilized to examine levels of various coping strategies among study participants. Participants were presented the prompt, “How likely are you to partake in the following behaviors” and then asked to rate items on a scale of 1 = “not at all likely” to 4 = “very likely,” meaning higher scores indicate that they are more likely to engage in that particular coping strategy. Six domains were yielded in the measures debut, showing construct validity (Quayhagen & Quayhagen, 1982). Five of the CSI Subscales were used in this study. The Affectivity subscale (α = 0.696) was used to measure emotional affect and reactivity with 8 items such as “Express worry about the situation” and “express pleasure over happenings.” The Existential Growth subscale (α = 0.837) examined positive and mindful outlook with 8 items such as “find new faith or truth about life” or “try and find fair compromise.” The Fantasy subscale (α = 0.829) consisted of 5 items that included “convince self-things will be different” and “wish things would go away.” The Problem-Solving (α = 0.742) subscale was also 5 items that included “mentally rehearse plan to handle problem” and “make alternate plans for situation.” Finally, Minimization of Threat (α = 0.467) included 4 items such as “express happiness over the situation” and “go out to forget the problem.

Depression, anxiety, and stress

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995) was utilized to assess adjustment symptoms among study participants. Reliability and validity for the DASS-21 has been established in multiple populations including non-clinical, college students, and cross-culturally (Bibi et al., 2020; Henry & Crawford, 2005; Osman et al., 2012). The inventory consists of 3 sub-scales, Stress, Depression, and Anxiety, each consisting of 7 items in which participants respond along a scale of 0 = “Does not apply to me at all,” 1 = “Applied to me to some degree, or some of the time,” 2 = Applied to me a considerable degree, or a good part of the time,” and 3 = “Applied to me very much, or most of the time,” meaning that higher scores indicate that this form of stress applies to them more often. The Stress subscale (α = 0.774) included 7 items, including “I found it difficult to relax” and “I felt I was using a lot of nervous energy.” The Depression Subscale also included 7 items such as “I felt that I had nothing to look forward to” and “I felt that I wasn’t worth much as a person.” Finally, the Anxiety subscale (α = 0.882) included 7 items such as “I felt I was close to panic” and “I felt scared without any good reason.”

Data analysis

Intercorrelations and descriptive summaries between study variables, including Means, Standard Deviations, and Cronbach’s Alphas (α) can be found in Table 2. Demographic variables were included as covariates in the study to account for variance that is explained by biological sex, age, and race/ethnicity.

Hierarchical Multiple Regression (see Table 3) was utilized to examine first the predictive value of the perceived difficulty in Spring 2020 and subsequently the moderating variables and interaction terms on depression, anxiety, stress symptoms (DASS, Lovibond & Lovibond, 1995). Age, race, and biological sex were first entered as covariates before entering perceived difficulty of the spring 2020 semester as a predictor. The individual coping strategies from the CSI (Quayhagen & Quayhagen, 1982) was then entered into the third step to see predictive power. The final step included the interaction terms for each coping strategy and perceived difficulty in the spring 2020 semester. Because of the nature of these analyses, all predictor and moderator variables were mean centered before creating interaction terms.

Results

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations can be found in Tables 1 and 2. Of note, the perceived difficulty in spring 2020 was significantly correlated with stress (r = .14, p < .05), depressive (r = .20, p < .01), and anxiety (r = .20, p < .01) symptoms. Multicollinearity was not of concern, however it should be noted that zero-order correlations are relatively small in magnitude (See Table 2).

Table 3 summarizes the hierarchical multiple regression results. The first step of the equation only examined the covaries (biological sex, racial identity, and age). None of the models in this step were significant, nor did they uniquely yield a significant association with the outcome variables (stress, depression, anxiety). Answering Research Question 1, the second step examined the perceived difficulty in Spring 2020 as the predictor variable, while controlling for biological sex, racial identity, and age and its association with stress (R2 = 0.03, F(4, 247) = 1.87, p > .05), depression (R2 = 0.56, F(4, 247) = 3.63, p < .001), and anxiety (R2 = 0.51, F(4, 247) = 3.29, p < .05). In this context, perceived difficulty in spring 2020 was significantly associated with stress (β = 0.127, p < .01), depression (β = 0.178, p < .01), and anxiety (β = 0.188, p < .01) such that for those who perceived difficulty in spring 2020 greater, there was also a greater a prevalence of depression, anxiety, stress symptoms. This was in line with the hypothesis for research question 1 and past research.

The third step of the hierarchical multiple regression (Table 3) added the moderating variables to the equation for stress (R2 = 0.33, F(9, 247) = 12.88, p < .001), depression (R2 = 0.42, F(9, 247) = 19.16, p < .001), and anxiety (R2 = 0.35, F(9, 247) = 14.02, p < .001), to see how the variance changes in predicting the outcome variables. Across all 3 outcomes, perceived difficulty in spring 2020 still significantly predicted stress (β = 0.13, p < .01), depression (β = 0.15, p < .01), and anxiety (β = 0.17, p < .01) with coping strategies included in the equation. Further, some coping strategies in this equation yielded a significant association with the outcome variables. In the model predicting stress for step 3, affective coping (β = 0.38, p < .001) and fantasy coping (β = 0.17, p < .05) were positively associated with stress symptoms, while existential growth (β = − 0.26, p < .001) coping was negatively associated with stress symptoms. In the models predicting depression for step 3, affective coping (β = 0.40, p < .001), fantasy coping (β = 0.20, p < .001), and problem-solving coping (β = 0.18, p < .01) were positively associated with depressive symptoms, whereas existential growth coping (β = − 0.27, p < .001) was negatively associated with depressive symptoms. Finally, in the model predicting anxiety for this step, affective coping (β = 0.32, p < .001), existential growth coping (β = 0.20, p < .001), fantasy coping (β = 0.24, p < .001), problem solving coping (β = 0.17, p < .05) were all positively associated with anxiety symptoms.

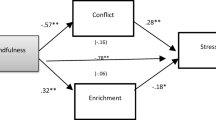

The fourth and final step answers research question 2. An interaction term was included for each coping strategy variable in the study with perceived difficulty in spring 2020 to test moderation with stress (R2 = 0.36, F(14, 247) = 9.41, p < .001), depression (R2 = 0.44, F(14, 247) = 13.27, p < .001), and anxiety (R2 = 0.38, F(14, 247) = 10.18, p < .001). All interaction terms were included in the equation for the three outcomes. Although each model in this step was significant, only one interaction yielded significance, only partially confirming the hypothesis for this research question. Specifically, the interaction of perceived difficulty in spring 2020 and problem-solving coping (β = 0.169, p < .05). Figure 1 shows the plot for this interaction. There was a significant interaction in that problem solving coping moderated the relationship between perceived spring 2020 difficulty and stress symptoms. Specifically, higher levels of problem-solving coping were associated with more positive relationship between spring perceived 2020 difficulty and stress symptoms.

Discussion

The current study sought to examine connections between retrospective perceived difficulty in the abrupt spring 2020 transition and fall 2020 adjustment symptoms in a sample of college students and see how coping strategies might have been associated with this relationship. The hypotheses were partially confirmed, finding that perceived difficulties were associated with higher rates of depression, anxiety, stress symptoms. This association was found to hold even when accounting for active (i.e., affective and problem-solving coping) and passive (i.e., existential growth and fantasy coping) coping strategies among college students. Further, it was, albeit surprisingly, noted that in the study sample, those who were high in problem solving coping strategies experienced a greater link between higher rates of spring 2020 difficulty and stress symptoms than those who were low in problem solving coping strategies.

Of note, it was quite surprising to see the different directional relationships between coping strategies and the other study variables. In the significant interaction of problem solving coping with perceived stress and DASS symptoms, it was surprising that problem solving coping appeared to be associated with increased symptoms, rather than a helpful strategy. One possible explanation for this could be allostatic load (Barthas et al., 2020; Kietzman & Gourley, 2020; Mayer et al., 2019) and that using more tangible resources were more taxing. It was also surprising to see a negative association between existential growth and depression and stress symptoms, but a positive association in anxiety symptoms in the pre-moderation analyses. One particular explanation for this could be that some participants were experiencing existential anxiety, the anthesis of existential growth such that individuals experience anxiety over situations related to mortality, meaninglessness, or guilt and regret (Tomaszek & Muchacka-Cymerman, 2020). Perhaps a feeling of directionlessness exacerbates anxiety symptoms in this sample.

Implications

The current study, although not causal linking, provides data that should be headed by educators, administrators of higher education, and clinicians. Perhaps one of the most important takeaways from this study is the time frame in which it focuses. The literature notes a cumulative impact that stress can have psychologically and physiologically. Direct and indirect connections have been drawn between cumulative stress and HPA axis activation and depressive symptoms (Shapero et al., 2018), which in turn could have maladaptive implications on social interactions (Barthas et al., 2020). At a chromosomal level, cumulative stress from childhood across the lifespan has also been connected to shortened telomeres (Mayer et al., 2019). As Kietzman and Gourley (2020) describe, indeed, minor stress is dealt with by our own internal mechanisms to be alleviated, however prolonged use with little reprieve potentially risks a habitual stress phenomenon that taxes out our resources – also known as allostatic load (Barthas et al., 2020; Kietzman & Gourley, 2020; Mayer et al., 2019). This can also occur at the child level such that resources to deal with stress used up at an early age (Kanner et al., 1991; Mize & Kliewer, 2017) may create difficulties later. In the context of the pandemic, educators, administrators, and clinicians alike, should be prepared for students and clients in the future whose allostatic load was built heavily during the pandemic and thus may require additional support in the future, consistent with concerns by the American Psychological Association (2020). We still do not know the long-ranging effects of the COVID-19 pandemic that is still ongoing as this study is written.

Educators may also find the results in the study helpful when considering supports they provide for their students. COVID-19 timeframe research has found instructor’s preparation, organization, and respectful environment was related to student learning support for online students (Samuels et al., 2021). Reducing obstacles and challenges within their limits of power, theoretically would reduce the foundational stressors’ impact. This is particularly important to keep in mind for students from underprivileged backgrounds. Through scholarships, student loans, and personal savings, students from underprivileged and low-income backgrounds have been able to have the privilege of receiving a college education (Frost et al., 2020). As students have received their education, they have gained access to library services and physical space, high quality internet provided with their student status, and in turn the ability to communicate with their instructors through email and office hours and learn with their peers. All of these resources disappeared with the emergency transition to online learning due to COVID-19. Yet, the expectation to perform to a passing level and receive credit was still present. With what we know now, perhaps a takeaway from this study if for educators to increase their flexibility.

Clinicians may find it useful to focus on identifying the direct contributors to stress symptoms. Although the interaction showed problem solving strategies to be a hindrance, this does not mean emotional affectivity, or some passive strategies are not potentially helpful or that active coping strategies are without merit. Indeed, it was at one point a question as to whether coping strategies served as a mediator in the relationship between perceived difficulty in spring 2020 and depression, anxiety, stress symptoms. This would in fact be consistent with Ara et al. (2017) who found problem focused and emotion focused coping to mediate the path between relationship quality and depressive symptoms. However, it was determined that the target research question was about context (Eisenbarth, 2012; Folkman, 2008; Kavčič et al., 2022), not mechanistic. Ara et al. (2017) were indeed similar variables to some COVID-19 related stressors (López-Castro et al., 2021; Marler et al., 2021). Because the current study did not collect relationship qualities, coping strategies not considered statistically significant in this study should still be considered in future research – Again, prior to the moderation analyses, passive coping strategies, in particular fantasy coping and existential growth coping appeared to have just as strong of a connection to depression, anxiety, stress symptoms as active coping, further supporting the usefulness of both active and passive strategies in managing mental health symptoms. It is likely, that problem solving coping held so strongly in the moderation because of the tangible nature of improving or maintain academically during the 2020 semester. But again, it is possible that this was overwhelming with the many demands students were experiencing at the time.

Again, the literature shows evidence of healthy coping strategies and their associations with lower rates of adjustment (AlHadi et al., 2021; Eisenbarth, 2012; Folkman, 2008; Kavčič et al., 2022; Park et al., 2008, 2021). Clinicians should continue their work in providing clients with a toolbox of strategies to help alleviate stress both in the short-term and long-term. Educators can also be of assistance by being mindful of potential stressors and providing reasonable flexibility and support to reduce contributions to academic related stressors.

Limitations

It is important to highlight the study’s limitations. First, there is always a risk of participants being dishonest when using self-report survey data. Efforts were made to minimize this by including control questions in the survey, and data cleaning procedures were conducted in anticipation of this limitation. Further, the data are correlational and cross-sectional, and not experimental nor longitudinal. Thus, participants had to retrospectively report their difficulty from Spring 2020. It would not be ethical to set up an experimental study for these research questions. However, perhaps the study would have benefited from asking specific questions at the time of COVID-19 pandemic onset and followed up the next semester and investigated social support and employment as covariates as both can have impacts on adjustment. Yet, the data still provide an interesting snapshot in the context of the pandemic. It should also be noted that the examined symptoms of stress, anxiety, and depression are only symptoms of adjustment and not indicative of clinical diagnoses of depression or anxiety as defined in the DSM-5TR (APA, 2022; Park et al., 2021; Reichenberg & Seligman).

It is also important to acknowledge uninvestigated variables for this study. Factors such as health anxiety were not gathered at data collection and in turn not controlled for in the analyses. It is possible examined symptoms were affiliated in part by worries of contracting the virus and uncertainty of next stages of the pandemic (Kibbey et al., 2021). Additionally, several studies on depression, anxiety, stress, and adjustment report gender influences, however, being that the sample was more than three quarters female and covariate analyses revealed no association with biological sex, this was not investigated. It is also possible that results would have been stronger had the data been collected in a different region or across multiple regions. Since the study was collected in the District of Columbia, Maryland, Virginia (DMV) region, perhaps participants were experiencing less difficulty and distress than in other regions that would be considered “hotspots” as described by Park et al. (2021) and Maroko et al. (2020). It would have been interesting to see how symptoms such as this and coping strategies would have persisted. Finally, attrition and number of enrolled credits across the 2020 would have been useful as the data only reflects students who remained and did not have to drop out of school.

Despite these limitations, this study is consistent with prior stress research (e.g., Hamzah et al., 2019; Kulig & Persky, 2017; Park et al., 2021; Peleg et al., 2016; Zivin et al., 2009) and expands on the literature, providing insight to a unique point in time that has been of interests to scholars (e.g., Galea et al., 2020; López-Castro et al., 2021; Park et al., 2008, 2021; Xia et al., 2021) and adding to the breadth knowledge of how coping skills relate to stress in times of global strife.

Conclusion

Although these data are correlational, they capture an important snapshot during a unique time that clinicians and administrators can learn from. Clinicians should be prepared to work with individuals needing to process what has been lost in the last couple of years. The findings in this study provide insight into potential coping strategies that may or may not be useful in the context of the pandemic stress. Further, Colleges and Universities should be prepared for a continual shift in online flexibility. As it stands, perhaps students have adapted favorably to online learning, finding in person learning less desirable. Higher education should consider implementing policies in their institutions that could help mitigate negative impact from abrupt changes. Indeed, higher education would be more prepared now than in the time of the study. However, working to ease the uncertainty of what would happen could go a long way for student success and student mental health alike.

Data availability

Datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to study protocol and confidentiality. However, codebooks and syntax for the data are available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

Aldwin, C. M. (2007). Stress, coping, and development (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

AlHadi, A. N., Alarabi, M. A., & AlMansoor, K. M. (2021). Mental health and its association with coping strategies and intolerance of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic among the general population in Saudi Arabia: Cross-sectional study. BMC Psychiatry, 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-021-03370-4

American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed-Text Revision).

American Psychological Association (2020). Stress in America™ 2020: A national mental health crisis. https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/stress/2020/report-october

Ara, E. M., Talepasand, S., & Rezaei, A. M. (2017). A structural equation model of depression based on interpersonal relationships: The mediating role of coping strategies and loneliness. Arch Neuropsychiatry, 54, 125–130. https://doi.org/10.5152/npa.2017.12711

Arënliu, A., Bërxulli, D., Perolli-Shehu, B., Kransniqi, B., Gola, A., & Hyseni, F. (2021). Anxiety and depression among kosovar university students during the initial phase of outbreak and lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic. Health Psychology and Behavioral Medicine, 9(1), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/21642850.2021.1903327

Barthas, F., Hu, M. Y., Siniscalchi, M. J., Ali, F., Mineur, Y. S., Picciotto, M. R., & Kwan, A. C. (2020). Cumulative effects of stress on reward-guided actions and prefrontal cortical activity. Biological Psychiatry, 88(7), 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.02.008

Bell, C. J., Boden, J. M., Horwood, L. J., & Mulder, R. T. (2017). The role of peri-traumatic stress and disruption distress in predicting symptoms of major depression following exposure to a natural disaster. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 711–718. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417691852

Bibi, A., Lin, M., Zhang, X. C., & Margraf, J. (2020). Psychometric properties and measurement invariance of depression, anxiety, and stress scales (DASS-21) across cultures. Internaltional Journal of Psychology, 55(6), 916–925. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12671

Bozkurt, A., Jung, I., Xiao, J., Vladimirschi, V., Schuwer, R., Egorov, G., Lambert, S., Al-Freih, M., Pete, J., Olcott, D., Rodes, V., Araciaga, I., Bali, M., Alvarez, A., Roberts, J., Pazurek, A., Raffaghelli, J. E., Panagiotou, N., de Coëtlogon, P., & Paskevicius, M. (2020). A global outlook to the interruption of education due to COVID-19 pandemic: Navigating in a time of uncertainty and crisis. Asian Journal of Distance Education, 15(1), 1-126. Retrieved from http://www.asianjde.com/ojs/index.php/AsianJDE/article/view/462

Broglia, E., Millings, A., & Barkham, M. (2017). Challenges to addressing student mental health in embedded counselling ser- vices: A survey of UK higher and further education institutions. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1370695

Cavanaugh, J., & Stephen, S. J. (2015). Outcomes in online vs. face-to-face courses. Online Learning, 19(2). https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v19i2.454

Choi, N. G., Hegel, M. T., Sirrianni, L., Marinucci, M. L., & Bruce, M. L. (2012). Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(11), 668–674. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2012.07.003

DAAD. (2020). COVID-19 impact on international higher education: studies & forecasts. https://www.daad.de/en/information-services-for-higher-education-institutions/centre-of-competence/COVID-19-impact-on-international-higher-education-studies-and-forecasts/#Global%20and%20cross-national%20analyses

Di Renzo, L., Gualtieri, P., Cinelli, G., Bigioni, G., Soldati, L., Attinà, A., Bianco, F. F., Caparello, G., Camodeca, V., Carrano, E., Ferraro, S., Giannattasio, S., Leggeri, C., Rampello, T., Presti, L. L., Tarsitano, M. G., & De Lorenzo, A. (2020). Psychological aspects and eating habits during COVID-19 home confinement: Results of EHLC-COVID-19 Italian online survey. Nutrients, 12(7), Article 2152. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu12072152

Eisenbarth, C. (2012). Coping profiles and psychological distress: A cluster analysis. North American Journal of Psychology, 14(3), 485–496.

El Said (2021). How did the COVID-19 pandemic affect higher education learning experience? An empirical investigation of learners’ academic performance at a university in a developing country. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2021, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2021/6649524

Elmer, T., Mepham, K., Stadtfeld, C., & Capraro, V. (2020). Students under lockdown: Comparisons of students’ social networks and mental health before and during the COVID-19 crisis in Switzerland. PLoS One, 15(7), e0236337. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0236337

Folkman, S. (2008). The case for positive emotions in the stress process. Anxiety Stress and Coping, 21, 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615800701740457

Folk, J. B., Schiel, M. A., Oblath, R., Feuer, V., Sharma, A., Khan, S., Boan, B., Kulkarni, C., Ramtekkar, U., Hawks, J., Fornari, V., Fortuna, L. R., & Myers, K. M. (2022). The transition of academic mental health clinics to telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 61(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2021.06.003

Frost, N. D., Graham, S. R., Steg, A. M. R., Jones, T., Pankey, T., & Martinez, E. M. (2020). Bridging the gap: Addressing the mental health needs of underrepresented collegiate students in psychology training clinics. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 14(2), 138–144. https://doi.org/10.1037/tep0000282

Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of Covid-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. The Journal of the American Medical Association Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–818. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

Garriott, P. O., & Nisle, S. (2018). Stress, coping, and perceived academic goal progress in first-generation collgee students: The role of institutional supports. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education, 11(4), 436–450. https://doi.org/10.1037/dhe0000068

Hamzah, N. S. A., Farid, N. D. N., Yahya, A., Chin, C., Su, T. T., Rampal, S. R. L., & Dahlui, M. (2019). Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(12), 3545–3557. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01537-y

Henry, J. D., & Crawford, J. R. (2005). The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 44, 227–239. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466505X29657

Huang, Y., Su, X., Si, M., Xiao, W., Wang, H., Wang, W., Gu, X., Ma, L., Li, J., Zhang, S., Ren, Z., & Qiao, Y. (2021). The impacts of coping style and perceived social support on mental health of undergraduate students during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic in China: A multicenter survey. BMC Psychiatry, 21(530), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-012-03546-y

Islam, S., Sujan, S. H., Tasnim, R., Sikder, T., Potenza, M. N., & van Os, J. (2020). Psychological responses during the COVID-19 outbreak among university students in Bangladesh. PLoS One, 15(12), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245083

Kanner, A. D., Feldman, S. S., Weinberger, D. A., & Ford, M. E. (1991). Uplifts, hassles, and adaptational outcomes in early adolescents. In R. S. Lazarus & A. Monat (Eds.), Stress and coping: An anthology (3rd ed., pp. 158–181). Columbia University Press.

Kavčič, T., Avsec, A., & Kocjan, G. Z. (2022). Coping profiles and their association with psychological functioning: A latent profile analysis of coping strategies during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 185, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.11287

Kibbey, M. M., Fedorenko, E. J., & Farris, S. G. (2021). Anxiety depression and health anxiety in undergraduate students living in initial US outbreak “hotspot” during COVID-19 pandemic. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 50(5), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2020.1853805

Kietzman, H. W., & Gourley, S. L. (2020). Cumulative stress burden on motivated action revealed. Biological Psychiatry, 88(7), 514–516. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.07.010

Kramer, A., & Kramer, K. Z. (2020). The potential impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on occupational status, work from home, and occupational mobility. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119, Article 103442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103442

Kulig, C. E., & Persky, A. M. (2017). Transition and student well- being—why we need to start the conversation. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 81(6), 100.

Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, coping and appraisal. Guilford Press.

López-Castro, T., Brandt, L., Anthonipillai, N. J., Espinosa, A., & Melara, R. (2021). PLoS One, 16(4), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1731/journal.pone.0249768

Lorenzo-Alvarez, R., Rudolphi-Solero, T., Ruiz-Gomez, M. J., & Sendra-Portero, F. (2019). Medical student education for abdominal radiographs in a 3D virtual classroom versus traditional classroom: A randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Roentgenology, 213(3), 644–650. https://doi.org/10.2214/AJR.19.21131

Lovibond, P. F., & Lovibond, S. H. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) with the Beck depression and anxiety inventories. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33, 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

Luo, Y., Chua, C. R., Xiong, Z., Ho, R. C., & Ho, C. S. H. (2021). A systematic review of the impact of viral respiratory epidemics on mental health: An implication on the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 23(11), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.565098

Mak, I. W. C., Chu, C. M., Pan, P. C., Yiu, M. G. C., & Chan, V. L. (2009). Long-term psychiatric morbidities among SARS survivors. General Hospital Psychiatry, 31, 318–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2009.03.001

Marler, E. K., Bruce, M. J., Abaoud, A., Henrichsen, C., Suksatan, W., Homvisetvongsa, S., & Matsuo, H. (2021). The impact of COVID-19 on university students’ academic motivation, social connection, and psychological well-being. Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl0000294

Maroko, A. R., Nash, D., & Pavilonis, B. (2020). Covid-19 and inequity: A comparative spatial analysis of New York City and Chicago hot spots. medRxiv.

Mayer, S. E., Prather, A. A., Peterman, E., Lin, J., Arenander, J., Coccia, M., Shields, G. S., Slavich, G. M., & Epel, E. S. (2019) Cumulative lifetime stress exposure and leukocyte telomere length attrition: The unique role of stressor duration and exposure timing. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 104, 210–218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2019.03.002

Mize, J. L., & Kliewer, W. (2017). Domain-specific daily hassles, anxiety, and delinquent behavior among low-income, urban youth. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 53, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2017.09.003

Mustaffa, S., Aziz, R., Mahmood, M. N., & Shuib, S. (2014). Depression and suicidal ideation among university students. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 116, 4205–4208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2014.01.917

Nyer, P. (2019). The relative effectiveness of online lecture methods on student test scores in a business course. Open Journal of Business and Management, 8, 1648–1658. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojbm.2019.74115

Odriozola-González, P., Planchuelo-Gómez, A., Irurtia, M. J., & de Luis-García, R. (2020). Psychological effects of the COVID-19 outbreak and lockdown among students and workers of a Spanish university. Psychiatry Research, 290, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113108

Othman, N., Ahmad, F., El Morr, C., & Ritvo, P. (2019). Perceived impact of contextual determinants on depression, anxiety, and dress: A survey with university students. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 13(17), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-019-0275-x

Osman, A., Wong, J. L., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S., Gutierrez, P. M., & Lozano, G. (2012). The depression anxiety stress Scales—21 (DASS‐21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(12), 1322–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21908

Pappa, S., Ntella, V., Giannakas, T., Giannakoulis, V. G., Papoutsi, E., & Katsaounou, P. (2020). Prevalence of depression, anxiety, and insomnia among healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Brain Behavior and Immunity, 88, 901–907. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.026

Park, C. L., Aldwin, C. M., Fenster, J. R., & Snyder, L. B. (2008). Path- ways to posttraumatic growth versus posttraumatic stress: Coping and emotional reactions following the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 78(3), 300–312. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014054

Park, C. L., Finkelstein-Fox, L., Russell, B. S., Fendrich, M., Hutchison, M., & Becker, J. (2021). Psychological resilience early in the COVID-19 pandemic: Stressors, resources, and coping strategies in a national sample of Americans. American Psychologist, 76(5), 715–728. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000813.supp

Passavanti, M., Argentieri, A., Barbieri, D. M., Lou, B., Wijayaratna, K., Mirhosseini, A. S. F., Wang, F., Naseri, S., Qamhia, I., Tangerås, M., Pelliciari, M., & Ho, C. (2021). The psychological impact of COVID-19 and restrictive measures in the world. Journal of Affective Disorders, 283, 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.01.020

Peleg, O., Deutch, C., & Dan, O. (2016). Test anxiety among female college students and its relation to perceived parental academic expectations and differentiation of self. Learning and Individual Differences, 49, 428–436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.06.010

Quayhagen, M. P., & Quayhagen, M. (1982). Coping with conflict. Measurement of age-related patterns. Research on Aging, 4(3), 364–377.

Reichenberg, L. W., & Seligman, L. (2016). Anxiety Disorders. Selecting effective treatments: A comprehensive, systematic guide to treating mental disorders (5th ed.). Wiley.

Ren, Z., Xin, Y., Ge, J., Zhao, Z., Liu, D., Ho, R. C. M., & Ho, C. S. H. (2021). Psychological impact of COVID-19 on college students after school reopening: A cross-sectional study based on machine learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 29(12), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641806

Rovai, A. P., & Wighting, M. J. (2005). Feelings of alienation and community among higher education students in a virtual classroom. The Internet and Higher Education, 8(2), 97–110. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2005.03.001

Samuels, M. A. B., Samuels, S. M., & Peditto, K. (2021). Instructor factors predicting student support: Psychology course feedback following COVID-19 rapid shift to online learning. Scholarship of teaching and learning in psychology. Advance Online Publication. https://doi.org/10.1037/stl00000272

Serafim, A. P., Durães, R. S. S., Rocca, C. C. A., Gonçalves, P. D., Saffi, F., Cappellozza, A., Paulino, M., Dumas-Diniz, R., Brissos, S., Brites, R., Alho, L., & Lotufo-Neto, F. (2021). Exploratory study on the psychological impact of COVID-19 on the general brazilian population. PLoS One, 16(2), e0245868. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0245868

Shapero, B. G., Curley, E. E., Black, C. L., & Alloy, L. B. (2018). The interactive association of proximal life stress and cumulative HPA axis functioning with depressive symptoms. Anxiety and Depression Association of America, 36, 1089–1101. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22957

Soesmanto, T., & Bonner, S. (2019). Dual mode delivery in an introductory statistics course: Design and evaluation. Journal of Statistics and Education, 27(2), 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/10691898.2019.1608874

Starcke, K., & Brand, M. (2016). Effects of stress on decisions under uncertainty: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 142, 909–933. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000060

Tan, J. (2019). Contributing factors of the effectiveness of delivering business technology courses: On-ground versus online. International Journal of Accounting and Financial Reporting, 9(4), 19–40. https://doi.org/10.5296/ijafr.v9i4.15371

Tomaszek, K., & Muchacka-Cymerman, A. (2020). Thinking about my existence during COVID-19, I feel anxiety and awe – the mediating role of existential anxiety and life satisfaction on the relationship between PTSD symptoms and post-traumatic growth. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2, 30–84. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17197062

Vintila, M., Tudorel, O. I., Stefan, A., Ivanoff, A., & Bucur, V. (2022). Emotional distress and coping strategies in COVID-19 anxiety. Current Psychology. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02690-8

Xia, W., Li, L. M. W., Jiang, D., & Liu, S. (2021). Dynamics of stress and emotional experiences during COVID-19: Results from two 14-day daily diary studies. International Journal of Stress Management, 28(4), 256–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000234

Xiao, H., Zhang, Y., Kong, D., Li, S., & Yang, N. (2020). Social capital and sleep quality in individuals who self-isolated for 14 days during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in January 2020 in China. Medical Science Monitor, 26, Article e923921. https://doi.org/10.12659/MSM.92392

Zivin, K., Eisenber, D., Gollust, S. E., & Golberstein, E. (2009). Persistence of mental health problems and needs in a college student population. Journal of Affective Disorders, 117(3), 180–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.01.001

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Informed consent

Informed consent was given, and the study meets ethical compliance for human subject’s research and received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval at George Mason University (Protocol #1645061-1).

Conflict of interest

No conflict of interest to disclose. Institutional Review Board Approval was given at George Mason University (Protocol #1645061-1).

Additional information

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Mize, J.L. Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and coping strategies in the context of the sudden course modality shift in the Spring 2020 semester. Curr Psychol 43, 3944–3955 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04566-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04566-5