Abstract

As the science of wellbeing has grown, universities have adopted the challenge of prioritizing the wellbeing of students. Positive psychology interventions (PPIs), activities designed to increase the frequency of positive emotions and experiences, which help to facilitate the use of actions and thoughts that lead to human flourishing, are being increasingly used worldwide. Known to boost wellbeing and a number of other variables, it nonetheless remains unknown whether their use can influence other variables in non-Western cultures. In this study, we determined the impact of PPIs on a variety of wellbeing outcomes. The 6-week PPI program was conducted in the United Arab Emirates on Emirati university students (n = 120) who reported more positive emotion and overall balance of feelings that favored positivity over time relative to a control group. Yet, there was no effect found on negative emotions, life satisfaction, perceived stress, fear of happiness, locus of control, or somatic symptoms, and no effect on levels of collectivism or individualism. Our findings nonetheless support the use of PPIs in higher education as they show an increase in the experience of positive emotion, with this in itself bringing positive life outcomes, and no negative impact on culture. Our findings serve to build a foundation for understanding for whom PPIs work best - and least - around the world.

Similar content being viewed by others

Academic institutions are increasingly being held accountable for the wellbeing of their students (Baik et al., 2019; Hernández-Torrano et al., 2020). Rates of mental illness and psychological distress peak in young adulthood and resist a return to pre-university levels (Bewick et al., 2010; de Girolamo et al., 2012; Macaskill, 2013). A way to improve this is via positive psychology interventions (PPIs), which are strategies to facilitate the actions, thoughts and emotions conducive towards wellbeing. These can be deployed in many settings, including universities. Yet, these strategies are often derived from Western contexts and may be counterproductive in that their promotion may undermine cultural values, which in themselves contribute to wellbeing in non-Western nations. Further, there is increasing interest in the specificity of such interventions; overall, they work, but at a more granular level, they may not work in the same way or as effectively for everyone. This study, based in the United Arab Emirates (UAE), addressed this line of inquiry; while PPIs are known to increase wellbeing and decrease illbeing, it was of interest to see whether they had the same impact in a non-Western nation, as well as what changes they had on levels of individualism, locus of control, and other variables.

Positive Psychology Interventions (PPIs)

PPIs are the empirically validated activities designed to increase the frequency of positive emotions and experiences, as well as perceptions of life satisfaction. These targets comprise the standard means of understanding wellbeing (Parks & Biswas-Diener, 2013) and PPIs facilitate the use of actions and cognitions that lead to it. The range of PPIs is vast (e.g. Walsh et al., 2016; Woodworth et al., 2016) and can include acts of kindness (Curry et al., 2018), goal pursuits (Klug & Maier, 2015), and imagining time as scarce (Layous et al., 2018). Meta-analyses show that PPIs reliably improve the experience of positive emotion and life satisfaction; they also decrease negative emotionality in a sustainable manner relative to control groups, with changes lasting up to one year post-intervention (Bolier et al., 2013; Carr et al., 2020; Chakhssi et al., 2018; Hendriks, Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2016). PPIs also protect against stress and attenuate symptoms of mental illness and emotional distress (Layous et al., 2014; Riches et al., 2016; Shin & Lyubomirsky, 2016; Taylor et al., 2017). More broadly, greater wellbeing lends itself to many positive outcomes, i.e., pro-social action (Rand et al., 2015; Son & Wilson, 2012), better relationships (Mehl et al., 2010; Richards & Huppert, 2011), stronger academic performance (Howell, 2009; Suldo et al., 2011), and workplace productivity (Krekel et al., 2019) as examples.

PPIs and Culture

While personality factors have been the most widely studied variable of “intervention fit” to date (i.e., Mongrain et al., 2018; Schueller, 2010, 2012; Senf & Liau, 2013), culture and religion also influence wellbeing (e.g., Ngamaba & Soni, 2018; Ye et al., 2015). In fact, scholars encourage positive psychology to consider wellbeing from diverse cultural views (Diener et al., 2018; Wong & Roy, 2017), especially in the Middle East/North Africa region where the literature is scant (Lambert et al., 2015; Rao et al., 2015). Reviews nonetheless show that the dissemination of PPIs is growing globally (Hendriks, Schotanus-Dijkstra et al., 2018; Kim et al., 2018), with one third of PPI studies now occuring in non-Western countries (Hendriks, Warren et al., 2018). Still, Hendriks et al. (2020) found these studies reported far higher effect sizes or no efficacy. Much can be attributed to their low quality; yet, that cultural factors might be at work remained a possibility. This variability is not exceptional: even Western replication studies are not always successful in showing the same outcomes (e.g. Mongrain & Anselmo-Matthews, 2012).

In non-Western nations, these imported PPIs also come with their unacknowledged individualistic and democratic values (Bermant et al., 2011; Christopher & Hickinbottom, 2008; Joshanloo, 2013; Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021), and use as the norm, WEIRD participants (i.e., Western, Educated, Industrialized, Rich, and Democratic), limiting their generalizability to other parts of the world (Hendriks, Warren et al., 2018; Henrich et al., 2010). Western notions of individualism are intertwined in seemingly benign activities intended to increase wellbeing by acting on an autonomous self, e.g., self-efficacy, self-esteem, self-worth (Foody et al., 2013; Hendriks, Warren, et al., 2018; Wong & Roy, 2017; Yakushko & Blodgett, 2021). This ‘self’ focus is often at odds with an interdependent self (Brewer & Chen, 2007; Hashimoto & Yamagishi, 2013). Assumptions around the desire for and, universality of happiness are also rife (see Lutz & Passmore, 2019) despite the fact that many cultures do not explicitly pursue happiness. Joshanloo et al. (2014, 2015) reveal that in segments of Muslim populations (and elsewhere), there is a fear of happiness. A UAE study (Lambert, Passmore, & Joshanloo, 2019) confirmed that participants indeed held these beliefs, which were minimized through PPI use. This latter study, as well as another conducted in Kuwait (Lambert, Passmore, Scull et al., 2019) nonetheless tested the effects of eight and 14 week long PPI programs, both of which were successful in increasing the balance of positive affect and reports of life satisfaction.

Correlates of Wellbeing

While measures of positive and negative feelings as well as life satisfaction, that is, a subjective, cognitive judgement or belief about one’s life (Diener et al., 2009), often comprise how wellbeing is construed and the standard outcomes in most studies, other variables are also of interest; we examine cultural dimensions, locus of control, somatization, and stress.

Culture

Hofstede’s (2001) cultural dimensions classify nations on the dimensions of power distance (acceptance of class inequality), masculinity (competitiveness, assertiveness), uncertainty avoidance (valuing order and tradition), and individualism (the extent to which individuals are expected to follow personal interests over those supported by the group). With respect to the latter, the UAE is described,

“The United Arab Emirates, with a score of 25 is considered a collectivistic society. This is manifest in a close long-term commitment to the member ‘group’, be that a family, extended family, or extended relationships. Loyalty in a collectivist culture is paramount, and over-rides most other societal rules and regulations” (Hofstede Insight, n.d.).

Higher collectivism and lower individualism remain the norm in the UAE (Alteneiji, 2015; Engin & McKeown, 2017; Willemyns, 2008; Wright & Bennett, 2008). Yet, Hills and Atkins (2013) noted that although values and behavioral norms across UAE workplaces converged with Western work norms, cultural groups reverted to their personal values outside of work. As culture shapes social relationships, obligations, decisions, goals, and the development of the self, and individuals themselves select aspects of the culture that suit them best, there is great variance (Akkus et al., 2017; Steele & Lynch, 2013; Steel et al., 2018), requiring measures of adherence to such values.

Such nuances include (Triandis, 2001; Triandis & Suh, 2002): (1) Horizontal Individualism, where individuals desire to be unique and value individual autonomy, but view themselves as equal in importance to others and prefer not to stand out (e.g. Sweden, Denmark, Norway); (2) Vertical Individualism, where individuals strive to behave autonomously, and the notion of competition relative to others is prioritized (e.g. USA, UK, France); (3) Horizontal Collectivism, where individuals perceive themselves to be interdependent with, and equal to others in status and where sociability is prized (e.g. Brazil, Latin America); and (4) Vertical Collectivism, where hierarchy is valued, preference is for in-group goals, and duties as well as obligations are prioritized (e.g. India, Japan, Korea). The descriptions account for the degree to which cultures value equality (i.e., horizontality) or hierarchy (i.e., verticality), while espousing a focus on the self or others.

Higher scores in vertical individualism are associated with lower wellbeing (i.e., Humphrey et al., 2020; Zalewska & Zawadzka, 2016). Oishi’s (2000) study of 39 nations revealed that horizontal individualism was positively associated with life satisfaction, while vertical collectivism showed the opposite. Orientations have an effect on social dynamics which influence wellbeing. For example, a study in South Korea and the USA showed that pro-self individuals endorsed vertical individualistic values more strongly, while prosocial individuals endorsed more horizontal collectivistic values (Moon et al., 2018). Another study across Chinese and US cities showed that vertical individualism drove stigmatizing attitudes in the workplace (Rao et al., 2010). Further, employees who held horizontal collectivism values were more resilient against the impact of incivility and discrimination compared to those who held horizontal individualism values (Welbourne et al., 2015). As cultural orientations amplify wellbeing, we examine them here.

Locus of Control

Locus of control (LOC; Rotter, 1966) is also of interest. Those with an internal LOC see themselves as responsible for their outcomes and rely on their abilities to commit to goals. They are motivated by internal rewards, such as pleasure, interest, and achievement. In contrast, those with an external LOC believe their outcomes are determined by fate, luck, or other people, pursuing indirect action, such as gaining influence, and blaming others when things fail. LOC differences have varied outcomes. Externals may be at greater risk for depression and stress (Afifi, 2007; Griffin, 2014; Quevedo & Abella, 2014; Verme, 2009). Internals show greater goal progress and stronger performance as they believe effort drives the pursuit (Hortop et al., 2013; Kirkpatrick et al., 2008). This generates stronger emotional wellbeing (Hortrop et al., 2013). Indeed, internal LOC tends to be related to greater wellbeing (e.g. Knappe & Pinquart, 2009; Moore, 2007; Oladipo et al., 2013). Given its relevance for wellbeing, we examine it in the present study.

Physical Health

Also included is somatization, psychological distress expressed through physical ailment, which appears as a key construct in the Arab world (Al Busaidi, 2010; Al Gelban, 2009; El-Rufaie, 2005; Hamdan, 2009). Studies in Saudi Arabia (Becker, 2004) and Egypt (Alsaleem & Ghazwani, 2014) found that the prevalence of somatization to be comparable to international rates, while Wilkins et al. (2018), who studied somatization in a Qatar hospital, found that younger females and non-national Arab patients had twice as many complaints. It may be more socially acceptable and less stigmatizing to report ailments in this way (Wang et al., 2015).

Evidence supports the notion of wellbeing contributing to physical health (Diener et al., 2017; Ong et al., 2018). The use of PPIs as a means to boost wellbeing have been successful in minimizing self-reported limitations in physical health (Lambert et al., 2015), with positive correlations between the experience of positive affect and fewer reported health symptoms (Pettit et al., 2001; Pressman & Cohen, 2005). Physical health is related to mental health (Ryff et al., 2006; Ryff & Singer, 2008) and positive emotions mitigate the physiological and cognitive effects of negative emotions and stress (Frederickson et al., 2000; Segerstrom & Miller, 2004). Greater wellbeing also enables individuals to engage in better health behaviors (Lyubomirsky et al., 2005; Veenhoven, 2008).

Perceptions of Stress

Finally, university students experience significant stress during their academic years (Al Ghailani et al., 2018; January et al., 2018; Syed et al., 2018) and receive fewer supports (Arnett, 2006; Lambert, Abdulrehman et al., 2019). Stress relates negatively to life satisfaction and subjective wellbeing (Civitci, 2015; Coccia & Darling, 2016; Karaman et al., 2018). As PPIs attenuate stress, depression, and anxiety, as well as increase wellbeing, i.e., positive emotion and life satisfaction (Bolier et al., 2013; Carr et al., 2020; Hendriks et al., 2020; Weiss et al., 2016), they may be helpful with the strains of university life.

The Present Study

This quasi-experimental study evaluated changes in subjective wellbeing after participating in a 6-week PPI program relative to a control group. It examined the impact of such a program on aspects of wellbeing including locus of control, cultural orientation, reports of somatic symptoms and stress. We hypothesized that there would be a significant Time by Condition interaction, such that those in the treatment condition would indicate greater positive changes over time in comparison to those in the control condition.

Method

Participants

Participants were students at the first author’s former institution and the site of where ethics approval was granted. A total of 120 participants were used in the analysis (78% female), with 50 non-participants in the control condition and 70 participants in the treatment condition. Of those in the treatment condition, 21 participants (30%) provided data at all three time points. Of those in the control condition, 29 participants (58%) provided data at all three time points. The majority of participants (68%) were from the Emirate of Abu Dhabi and all were Emirati national citizens. Most participants (83%) were reportedly between the ages of 18 and 29 years old, but ages ranged from less than 17 years old to greater than 60 years old.

Procedure

A call for participation was sent across the College of Humanities and Social Sciences student body; those interested self-registered for the program, while non-participating students attending psychology classes taught by the first author were assigned to the control group. Four renditions of the multi-component positive psychology intervention program were run during the 2018–2019 academic year. As recommended (i.e. Mangan et al., 2020), each 6-week iteration was deliberately commenced a few weeks into the term to avoid capturing an overly optimistic start of term or unnaturally stressed exam period. Each iteration involved identical weekly sessions that lasted 1.5 h for six weeks, and was delivered by the primary author. Each session included a short lesson on the topic, group discussion, insight oriented questions, and positive psychology interventions to complete in the class and practise in the week. No incentives were given for participation and participants gave informed consent. Measures were taken online before, after, and three months post-treatment. Analyses was conducted by the remaining authors. The topics covered and PPIs used are noted in Table 1.

Measures

As English was the institutional language of instruction in which all students studied, scales were given in their English version. A total of seven scales were administered, which included;

Scale of Positive and Negative Experience (SPANE; Diener et al., 2009, 2010). The 12-item SPANE measures positive feelings (SPANE-P; the summation of six items; α = .91), negative feelings (SPANE-N; the summation of six items; α = .86), and the balance between the two (SPANE-B; calculated by subtracting the total score on the negative sub-scale from the total score on the positive sub-scale; α = .91). Participants are presented with a list of emotions (e.g. pleasant, unpleasant, happy, sad) and asked to rate how often they have experienced those feelings during the past 4 weeks on a 1 (Very rarely or never) to 5 (Very often or always) Likert scale. The SPANE has good reliability and validity (Diener et al., 2010), as well as high factor loadings for the SPANE-P and SPANE-N. The construct validity of the overall SPANE is good, with moderate to very high correlations with other measures.

Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985). The 5-item scale (α = .86) assesses an individual’s overall judgment of satisfaction with their life as a whole (Pavot & Diener, 2008). Items (e.g., “I am satisfied with my life”, “If I could live my life over, I would change almost nothing”) are rated on a 7-point scale with end points of 1 = strongly disagree and 7 = strongly agree. Scores range from 5 to 35, with the neutral point at 20. The SWLS has high internal consistency (0.79 and higher), while test-retest reliability and convergent validity is also high (Pavot & Diener, 1993).

Academic Locus of Control Scale (ALCS; Trice, 1985). The ALCS is a 28-item scale (α = .70) to measure students’ perceptions of the internal or external control they have over their educational outcomes. Lower scores indicate a more internal locus of control, while higher scores suggest a more external locus of control. Sample items include, “There are some subjects in which I could never do well” and “I feel I will someday make a real contribution to the world if I work hard at it” (reversed). Trice (1985) reported internal consistency for the scale to be .70.

The Perceived Stress Scale-10 (Cohen, Kamarck, & Mermelstein, 1983) is a 10-item scale (α = .82) measuring the perception of stress in the past month and degree to which situations in one’s life are appraised as unpredictable and uncontrollable. The scale is well used with a review showing it had good statistical properties (Lee, 2012) and was valid for use among undergraduate students. Items (e.g. “In the last month, how often have you been upset because of something that happened unexpectedly”) were scored on a0 (Never) to 4 (Very Often) scale.

The Somatic Symptom Scale - 8 (SSS-8; Gierk et al., 2014) assesses somatic symptom burden by an 8-item self-report scale (α = .68). Respondents rate how much they are bothered by symptoms within the last seven days on a 5-point scale (1 = Not at all, 5 = Very much). Items include stomach problems, back pain, sleep trouble, etc. It has high internal consistency and content validity.

Individualism and Collectivism Scale (Singelis et al., 1995; Triandis & Gelfland, 1998): These 16 items include 4 subscales (4 items each) which capture aspects of collectivism and individualism; this includes vertical (VC; α = .86) or horizontal (HC; α = .79) collectivism (seeing the self as part of a group and willing to accept hierarchy and inequality versus perceiving all members as equal) and vertical (VI; α = .71) or horizontal (HI; α = .73) individualism (seeing the self as independent and accepting that inequality exists, or that equality is the norm). The scale distinguishes between the orientations and asks respondents how they perceive the importance of the group/self with respect to it. The scale and its broader construct have been frequently used in the field of cross-cultural consumer psychology (e.g. Shavitt et al., 2006; Shavitt & Barnes, 2020).

Fear of Happiness Scale (FHS; Joshanloo, 2013; Joshanloo et al., 2014). The 5-item scale (α = .86) captures the stable belief that happiness is a sign of impending unhappiness. Each item is rated on a 1 (Strongly disagree) to 7 (Strongly agree) scale, and a total score is made up of the sum of all 5 items. The measure is considered reliable (Joshanloo, 2013) and with good statistical properties (Joshanloo et al., 2014, 2015). An example item includes, “I prefer not to be too joyful because usually joy is followed by sadness.”

Results

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was usedFootnote 1; this was necessary as data at each time point (level 1; L1) were nested within persons (level 2; L2). Condition was considered an L2 variable as it differed across individuals. Multilevel modeling allowed us to use data from all participants, even if they were not able to complete all three measurement. Each dependent measure was run with a separate two-level model. Time (L1) was centered and coded such that −1 = pre-treatment, 0 = immediately post-treatment, and 1 = 3-month post-treatment. Condition was coded such that 0 = Control and 1 = Treatment condition. We first ran an intercepts-only model to obtain an intraclass correlation for each dependent measures, which ranged from .52 to .76. The equations below are an example of the intercepts-only model used to test the positive emotions outcome.

Level 1: SPANE-Pij = β0j + eij.

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + u0j.

At Level 1, the positive affect score (SPANE-P) on occasion i for person j is a function of the mean SPANE-P score for person j (β0j), and a residual term around person j’s mean (eij). At Level 2, the mean SPANE-P score for person j (β0j) is a function of the grand mean for SPANE-P across all persons in the sample (γ00), and an intercept residual term signifying person j’s deviation from the grand mean (u0j).

We tested each model for random intercepts and random slopes using a cut-off of p = .10 to determine whether to include random effects (Nezlek & Mroziński, 2020). Each model was built beginning with the intercepts only model above, which displayed significant between-person residual variance in the intercepts for all dependent measures. Thus, random intercepts were included in all subsequent models, which allowed for the intercepts to vary by person.

We then tested a model that included effects of the L1 Time variable. This model tested whether fixed or random slopes were more appropriate for the predictor. Random slopes allow the slope of Time to vary by person, whereas fixed slopes hold the slope of Time consistent across people. Time was the only L1 variable and therefore the only variable that was tested for random slopes and only for a linear effect. Equations for the model of positive emotions (which had a random slope for Time) are shown as an example.

Level 1: SPANE-Pij = β0j + β1j(Time) + eij.

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + u0j.

β1j = γ10 + u1j.

In this model, at Level 1, a person’s SPANE-P score is now also a function of slope of Time (β1j(Time)). At Level 2, an individual’s slope of Time (β1j) is a function of the average slope (γ10), and the individual’s residual variance around the average slope (u1j).

Next, the Condition (L2) variable was added to the model. For those models with random slopes, a cross-level (Condition x Time) interaction was tested in addition to the main effects of Condition and Time that were tested for all outcomes. The main term of interest was the Time x Condition interaction, which tests the extent to which the effects of time were moderated by condition. A statistically significant Time x Condition interaction would indicate that participants in one group changed over time differently than participants in the other group, indicating treatment efficacy if this difference favored the treatment group. The main effects of Condition do not speak to treatment efficacy, but an overall difference between groups when scores at the three measurement time points were averaged within each group. Such differences may reflect different baseline starting points. Also, a main effect of Time would indicate an overall change over time on the outcome for both groups. Variables that were analyzed using random slopes – and tested for a Time x Condition interaction – included satisfaction with life, positive emotions, balance of emotions, and horizontal collectivism, as these outcomes exhibited statistically significant variance in individuals’ slopes for Time.

The formula below is an example of the equations testing a cross-level interaction for SPANE-P scores.

Level 1: SPANE-Pij = β0j + β1j(Time) + eij.

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + γ01(Condition) + u0j.

β1j = γ10 + γ11(Condition) + u1j.

In this model, Condition effects are added to Level 2, such that the mean of an individual’s score on SPANE-P is now also a function of the expected score change between treatment conditions (γ01(Condition)). The slope of an individual’s SPANE-P score is now also a function of the expected effect of Condition on the slope of Time (γ11(Condition)).

For all models that used fixed slopes (those testing negative emotions, somatic symptoms, locus of control, fear of happiness, perceived stress, horizontal individualism, vertical individualism and vertical collectivism), tests of the cross-level interactions were contraindicated. Since these outcomes did not exhibit statistically significant variance in individuals’ slopes for Time, the treatment Condition could not moderate the effects of Time, rendering no treatment efficacy with respect to these outcomes. These models were still tested for main effects of Condition and Time, but because these tests do not speak to treatment efficacy, they are not discussed in detail. Results from these models are in Table 2.

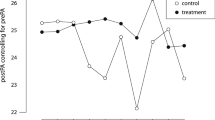

Positive Emotions

The final model for SPANE-P consisted of random intercepts and random slopes to test the effects of Time, Condition, and the Time x Condition interaction on positive emotions. There were no statistically significant main effects of Time or Condition on positive emotions, but there was a significant Time x Condition interaction (b = 1.15, SE = 0.47, 95% CI [0.21, 2.09], p = .017). Investigation of the simple slopes revealed that those in the treatment condition showed a statistically significant, positive simple slope for Time (b = 0.77, SE = 0.35, p = .028). This indicates that those in the treatment condition increased in self-reported positive emotions over time. In contrast, there was no statistically significant simple slope for Time in the control condition (b = −0.38, SE = 0.32, p = .248). Overall, there was a treatment effect for positive emotions. Table 3 shows regression coefficients from the final model for positive emotions (SPANE-P).

Balance of Emotions

The final model for balance between positive and negative emotions consisted of random intercepts and random slopes. There were no main effects of Time or Condition on the balance of emotions, but there was a statistically significant Time x Condition interaction (b = 2.33, SE = 0.84, 95% CI [0.67, 4.02], p = .007). Simple slopes analyses revealed that those in the treatment condition showed a statistically significant, positive simple slope for Time (b = 1.37, SE = 0.62, p = .030). This indicates that those in the treatment condition increased in the balance of emotions, showing a preponderance of positive relative to negative emotions over time for the treatment group. In contrast, in the control condition there was no statistically significant effect of Time on SPANE-B scores (b = −0.97, SE = 0.57, p = .093). Table 3 shows regression coefficients from the final model for balance of emotions.

Satisfaction with Life and Horizontal Collectivism

The final models for satisfaction with life and horizontal collectivism consisted of random intercepts and random slopes. There were no statistically significant Time x Condition interactions in either of these models, indicating that the treatment did not impact participants’ satisfaction with life or horizontal collectivism over time. There were no statistically significant main effects of Time or Condition on these dependent measures.

Discussion

This study contributes to the growing literature on PPIs and supports their effectiveness on certain aspects of wellbeing. Our hypothesis was partially supported, with participants in the PPI program reporting more positive emotion and an overall balance of feelings that favored positivity over time in comparison to the control group. This is not insignificant; the frequency of positive emotion contributes to beneficial outcomes. Posited by the Broaden and Build model (Fredrickson, 2006), the accumulation of positive emotions leads to greater cognitive flexibility and broader perceptions of possibility, as well as the building of physical, social, cognitive and psychological resources. As examples, the experience of positive emotion facilitates a resumption of pre-stress levels of functioning (Fredrickson et al., 2000), health-promoting actions such as not smoking, partaking in physical activity, and eating more healthily (Blanchflower et al., 2012; Grant et al., 2009), and longevity (Pressman & Cohen, 2012; Zhang & Han, 2016). Positive emotions also boost resiliency (Cohn et al., 2009), stimulate better decision-making (Chuang, 2007) and a sense of agency with which to make changes in life (Chang et al., 2017). Their experience also appears to reduce psychosomatic health symptoms (Karampas et al., 2016), although we did not observe that change in this study. A recent review explored the effects of PPIs on positive emotions specifically (Moskowitz et al., 2021), showing they were one of the key pathways through which physical and psychological health could be influenced.

At the same time, contrary to hypotheses, there was insufficient evidence that the PPI program affected participant’s life satisfaction, perceived stress, locus of control or somatic symptoms. This is curious as a previous study done in the UAE using the same program did show changes to life satisfaction (i.e. Lambert, Passmore, & Joshanloo, 2019); the only difference being that participants were Arab nationals of neighboring countries and not UAE nationals. Another study in neighboring Kuwait (i.e. Lambert, Passmore, Scull et al., 2019) also showed changes to life satisfaction, but only in university students, and not secondary school students. It should be noted that in these two studies, facilitators had a pre-existing relationship with participants, which was not the case here, and which may have impacted findings (i.e. Durlak et al., 2011; Stockings et al., 2016). Too few studies exist to determine whether these findings are indicative of a cultural nuance in life satisfaction, an artifact of the study conditions, or whether the population studied is too young to report significant life changes.

The nature of the life satisfaction measure may also have affected our findings. Morrison et al. (2011) found that respondents used factors such as employment, health, or standard of living to assess this question when overall living conditions were good, but more likely to use perceptions of societal success when their life conditions were difficult or when collectivist norms were evident. While wellbeing measures continue to be expanded to account for non-Western conceptualizations (i.e., Lambert et al., 2020); the inability to generate significant findings may have been its casualty. Similarly, Hendriks et al. (2018) suggest that the mere effect of being observed, known to treatment group participants, may have led them to respond in socially desirable ways and conform to the norm (McCambridge et al., 2014). This tendency has been noted in collective societies where the tall poppy syndrome, i.e., not wanting to stand out by making one’s self or life appear better than those of others (Diener & Biswas-Diener, 2019; Lalwani et al., 2006), may have led to more conservative reports of life satisfaction.

Finally, the absence of impact may well reflect just that. While the majority of published studies show PPI efficacy, the science is still building around questions of specificity; that is, for whom for such interventions work best and least, as well as reasons why. A greater number of studies conducted in non-Western countries as well as those showing a lack of efficacy can be useful in addressing these questions. The positivity bias can be a limiting factor in understanding the granular nature of such interventions; such exceptions may signal important information that would benefit the field as a whole (Hicks et al., 2015; van Assen et al., 2014).

At last and central to our inquiry, we found insufficient evidence of effect on collectivism or individualism levels. Decrease in vertical individualism and increase in horizontal individualism have been shown to be conducive to wellbeing (e.g., Rao et al., 2010; Welbourne et al., 2015). Yet, changes in individualism may suggest influence of PPIs on participants’ cultural values themselves, which may be perceived as undesirable. Our study found no such changes. This finding pertaining to these specific cultural dimensions, and the lack of effect on life satisfaction, may be due to a smaller sample undergoing an intervention over a short period of time. Based on power analysis, to detect a small-medium effect size (f = .15), 120 participants are needed, which is the total sample size of our study, but some conditions fell short of 60 participants. We recommend that future studies incorporate a minimum of 60 participants per group to detect such effects.

In sum, it appears that at least in short interventions, PPIs increase positive emotions, but we found insufficient evidence about whether they impacted the cultural dimensions of collectivism and individualism. However, this research is worthy of future investigation because if additional research finds that PPIs do not shift cultural values, it may be a tool that universities worldwide can deploy to counter negative emotional states over longer timeframes.

Future Directions and Limitations

One of the strengths of this study is that it was not limited to a one-time intervention but spread across six weeks with a follow-up three months post-treatment in relation to a control group. Still, our study could have benefitted from a longer analysis as tracking longitudinal changes relative to more frequent PPI use may have showed changes to somatization and stress, but most importantly to culture, particularly as it involves a set of deeply engrained, internalized set of beliefs and values, which may be resistant to short-term changes in behavior (Akkus et al., 2017; Steele & Lynch, 2013; Steel et al., 2018). Another strength was the timing of the intervention program. In semester long programs, participants often record poorer outcomes at the conclusion due to final exams and class assignments, with interventions serving to “stop the drop” (Mangan et al., 2020). In prior studies (i.e., Lambert, Passmore, & Joshanloo, 2019), the first author observed that students tended to report being highly optimistic at the start of term, only for their mood to drop once classes began, while in other cases, they may have felt the need to save face and project an image of perfection and happiness, common in collective cultures where one’s social reputation is primary (Han, 2016), and where impression management tends to occur more frequently in surveys (Riemer & Shavitt, 2011). Although our data was collected away from these high and low temporal points, it is unclear what extraneous variables like term dates have on this or other studies.

Another limitation includes the preponderance of female participants. The university has fewer male students and their small numbers may have influenced our findings; indeed, studies show that females tend to score more highly in horizonal collectivism and lower in vertical individualism (Kurman & Sriram, 2002; Lalwani & Shavitt, 2013; Nelson & Shavitt, 2002). A further limitation is that the lack of random assignment to conditions prevents firm causal conclusions; future research should conduct a randomized control trial. We also took an exploratory approach by examining treatment effects across a wide range of outcomes, without controlling the Type 1 error rate. Future research is needed to confirm that PPIs reliably boost positive emotions and emotional balance, and that our findings are not a statistical artifact. Finally, we did not track program compliance; thus, do not know if program benefits covary with dosage. Future research should explore this possibility.

While there remains work to do in discovering how PPIs impact non-Western participants, including on other cultural dimensions, such as power distance, masculinity, and uncertainty avoidance, ours considered this very question. While we did not find significant effects for many of the outcomes, the findings that are only intermittently statistically significant are still useful in helping establish the boundary conditions for PPIs across cultures. This work can aid in documenting which outcomes are likely affected by PPIs in the UAE, but also serve to build a repository of information used to facilitate the personalization of PPI treatment, a growing trend (Perna et al., 2018) where the empirical grouping of PPIs can allow predictions to be made in terms of which have the most value to consumers (Layous & Lyubomirsky, 2014). Necessarily knowing for whom they are not effective helps to build such specificity (Baños et al., 2016).

Further, in no case did the treatment group show worse change over time than the control group, suggesting that PPIs are acceptable within the UAE context. Regardless, it is unknown if the lack of effect is due to the length of the intervention or sample size; still, preliminary results suggest that PPIs can reliably boost positive emotions whilst preserving culture. While many universities teach remedial skills to cope with stress, depression and anxiety, few take a positive approach to building wellbeing (Lambert, Abdulrehman et al., 2019; White, 2016). Promoted in positive education (Green et al., 2011), an offshoot of positive psychology, the implementation of such programs through student affairs, counselling services, or as curricula is a growing trend setting students on a path to present and future success.

Conclusion

Offering PPIs in a university setting may be a route to strengthening wellbeing and countering the underutilization of mental health services, particularly in the region (Heath et al., 2016; Sewilam et al., 2015). They may also provide universities with the tools to boost wellbeing that are non-stigmatizing and inexpensive, as well as treatment and prevention focused. These could remedy high levels of depression, anxiety and stress frequently reported by students (Al Ghailani et al., 2018; January et al., 2018; Syed et al., 2018). As students return to campus post COVID-19, institutions may consider offering wellbeing skills to smooth this transition and promote wellbeing. Such interventions can also help students gain the long-term benefits of wellbeing, such that relationship, health, employment and performance benefits can be realized. Most importantly, as our findings suggest, these interventions can be used outside the cultural contexts for which they were designed and allay fears of undermining wellbeing, while paradoxically trying to build it.

Authors note: We confirm there is no conflict of interest for any of the co-authors involved in the writing or preparation of this paper, including the design and implementation of this study at all phases.

Data Availability Statement

The dataset analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Notes

Sensitivity analyses were run using repeated measures ANOVA to examine the Condition x Time interaction for each of the dependent variables. Results were largely consistent with the MLM findings reported in the main text, except there was an additional interaction showing a treatment effect for negative affect. Specifically, the treatment group’s negative affect statistically significantly decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 and increased from Time 2 to Time 3, whereas the control group’s negative affect increased from Time 1 to Time 2 and did not statistically significantly change from Time 2 to Time 3. However, these findings involved listwise deleting 70 cases, and we therefore feel more confident in the MLM results reported in the main text.

References

Akkuş, B., Postmes, T., & Stroebe, K. (2017). Community collectivism: A social dynamic approach to conceptualizing culture. PLoS One, 12(9), e0185725. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0185725.

Afifi, M. (2007). Health locus of control and depressive symptoms among adolescents in Alexandria, Egypt. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 13(5), 1043–1052. https://doi.org/10.26719/2007.13.5.1043.

Al Ghailani, B., Al Nuaimi, M. A., Al Mazrouei, A., Al Shehhi, E., Al Fahim, M., & Darwish, E. (2018). Well-being of residents in training programs of Abu Dhabi health services. Ibnosina Journal of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, 10, 77–82. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijmbs.ijmbs_12_18.

Al Busaidi, Z. Q. (2010). The concept of somatisation: A cross-cultural perspective. Sultan Qaboos University Medical Journal, 10(2), 180–186.

Al Gelban, K. S. (2009). Prevalence of psychological symptoms in Saudi secondary school girls in Abha, Saudi Arabia. Annals of Saudi Medicine, 29(4), 275–279. https://doi.org/10.4103/0256-4947.55308.

Alsaleem, M. A., & Ghazwani, A. Y. (2014). Screening for somatoform disorders among adult patients attending primary health care centers. AAMJ, 12, 35–57.

Alteneiji, E. A. (2015). Leadership cultural values of United Arab Emirates: The case of United Arab Emirates University. Master’s degree thesis, University of San Diego, CA. https://digital.sandiego.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1004&context=theses

Arnett, J. (2006). Emerging adulthood: Understanding the new way of coming of age. In J. Arnett & J. Tanner (Eds.), Emerging adults in America: Coming of age in the 21st century (pp. 3–20). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195309379.001.0001.

Baik, C., Larcombe, W., & Brooker, A. (2019). How universities can enhance student mental wellbeing: The student perspective. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(4), 674–687. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1576596.

Baños, R. M., Etchemendy, E., Carrillo-Vega, A., & Botella, C. (2016). Positive psychological interventions and information and communication technologies. In D. Villani, P. Cipresso, A. Gaggioli & G. Riva (Eds.), Integrating technology in positive psychology practice (pp. 38–58). IGI Global.

Becker, S. (2004). Detection of somatization and depression in primary care in Saudi Arabia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 39(12), 962–966. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-004-0835-4.

Bermant, G., Talwar, C., & Rozin, P. (2011). To celebrate positive psychology and extend its horizons. In K. M. Sheldon, T. B. Kashdan, & M. F. Steger (Eds.), Designing positive psychology: Taking stock and moving forward (pp. 430–438). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195373585.003.0029.

Bewick, B. M., Koutsopoulou, G., Miles, J., Slaa, E., & Barkham, M. (2010). Changes in undergraduate students’ psychological wellbeing as they progress through university. Studies in Higher Education, 35, 633–645. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216643.

Blanchflower, D. G., Oswald, A. J., & Stewart-Brown, S. (2012). Is psychological wellbeing linked to the consumption of fruit and vegetables? Social Indicators Research, 114(3), 785–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0173-y.

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 119. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119.

Brewer, M. B., & Chen, Y.-R. (2007). Where (who) are collectives in collectivism? Toward conceptual clarification of individualism and collectivism. Psychological Review, 114(1), 133–151. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.114.1.133.

Carr, A., Cullen, K., Keeney, C., Canning, C., Mooney, O., Chinseallaigh, E., & O’Dowd, A. (2020). Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1818807.

Chakhssi, F., Kraiss, J. T., Sommers-Spijkerman, M., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2018). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and distress in clinical samples with psychiatric or somatic disorders: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 18, 211. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1739-2.

Chang, Y.-P., Algoe, S. B., & Chen, L. H. (2017). Affective valence signals agency within and between individuals. Emotion, 17(2), 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000229.

Christopher, J., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396.

Chuang, S. C. (2007). Sadder but wiser or happier and smarter? A demonstration of judgment and decision-making. Journal of Psychology, 141, 63–76. https://doi.org/10.3200/JRLP.141.1.63-76.

Civitci, A. (2015). Perceived stress and life satisfaction in college students: Belonging and extracurricular participation as moderators. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 205, 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.09.077.

Coccia, C., & Darling, C. A. (2016). Having the time of their life: College student stress, dating and satisfaction with life. Stress and Health, 32, 28–35. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2575.

Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 386–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136404.

Cohn, M. A., Fredrickson, B. L., Brown, S. L., Mikels, J. A., & Conway, A. M. (2009). Happiness unpacked: Positive emotions increase life satisfaction by building resilience. Emotion, 9(3), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015952.

Curry, O. S., Rowland, L., Van Lissa, C. J., Zlotowitz, S., McAlaney, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2018). Happy to help? A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effects of performing acts of kindness on the well-being of the actor. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 76, 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2018.02.014.

de Girolamo, G., Dagani, J., Purcell, R., Cocchi, A., & McGorry, P. D. (2012). Age of onset of mental disorders and use of mental health services: Needs, opportunities and obstacles. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 21(1), 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1017/s2045796011000746.

Diener, E., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2019). Well-being interventions to improve societies. In J. Sachs, R. Layard, & J. Helliwell (Eds.), Global happiness policy report 2019 (pp. 94–116). Global Happiness Council

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The satisfaction with life scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49, 71–75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13.

Diener, E., Lucas, R. E., & Oishi, S. (2018). Advances and open questions in the science of subjective well-being. Collabra: Psychology, 4(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1525/collabra.115.

Diener, E., Pressman, S., Hunter, J., & Delgadillo-Chase, D. (2017). If, why, and when subjective well-being influences health, and future needed research. Applied Psychology: Health and Well-Being, 9(2), 133–167. https://doi.org/10.1111/aphw.12090.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2009). New measures of well-being: Flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 39, 247–266. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2354-4_12.

Diener, E., Wirtz, D., Tov, W., Kim-Prieto, C., Choi, D., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2010). New well-being measures: Short scales to assess flourishing and positive and negative feelings. Social Indicators Research, 97, 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y.

Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x.

El-Rufaie, O. E. (2005). Primary care psychiatry: Pertinent Arabian perspectives. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal, 11(3), 449–458 http://applications.emro.who.int/emhj/1103/11_3_2005_449_458.pdf?ua=1.

Engin, M., & McKeown, K. (2017). Motivation of Emirati males and females to study at higher education in the United Arab Emirates. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 41(5), 678–691. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2016.1159293.

Foody, M., Barnes-Holmes, Y., & Barnes-Holmes, D. (2013). On making people more positive and rational: The potential downsides of positive psychology interventions. In T. B. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 166–193). New Harbinger

Fredrickson, B. L. (2006). Unpacking positive emotions: Investigating the seeds of human flourishing. Journal of Positive Psychology, 1, 57–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760500510981.

Fredrickson, B. L., Mancuso, R. A., Branigan, C., & Tugade, M. M. (2000). The undoing effect of positive emotions. Motivation and Emotion, 24, 237–258. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1010796329158.

Gierk, B., Kohlmann, S., Kroenke, K., Spangenberg, L., Zenger, M., Brähler, E., & Löwe, B. (2014). The somatic symptom Scale-8 (SSS-8): A brief measure of somatic symptom burden. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 399–407. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.12179.

Grant, N., Wardle, J., & Steptoe, A. (2009). The relationship between life satisfaction and health behavior: A cross-cultural analysis of young adults. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 16, 259–268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12529-009-9032-x.

Green, S., Oades, L., & Robinson, P. (2011, April). Positive education: Creating flourishing students, staff and schools. Australian Psychological Society: InPsych https://www.psychology.org.au/publications/inpsych/2011/april/green/.

Griffin, D. P. (2014). Locus of control and psychological well-being: Separating the measurement of internal and external constructs: A pilot study. EKU Libraries Research Award for Undergraduates, 2. http://encompass.eku.edu/ugra/2014/2014/2

Hamdan, A. (2009). Mental health needs of Arab women. Health Care for Women International, 30(7), 593–611. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399330902928808

Han, K. H. (2016). The feeling of "face" in Confucian society: From a perspective of psychosocial equilibrium. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1055. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01055.

Hashimoto, H., & Yamagishi, T. (2013). Two faces of interdependence: Harmony seeking and rejection avoidance. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 16, 142–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12022.

Heath, P. J., Vogel, D. L., & Al-Darmaki, F. R. (2016). Help-seeking attitudes of United Arab Emirates students: Examining loss of face, stigma, and self-disclosure. The Counseling Psychologist, 44(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000015621149.

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2018). The efficacy of positive psychology interventions from non-Western countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 71–98. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.711.

Hendriks, T., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Jong, J., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2020). The efficacy of multi-component positive psychology interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Journal of Happiness Studies, 21(1), 357–390. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-019-00082-1.

Hendriks, T., Warren, M. A., Schotanus-Dijkstra, M., Hassankhan, A., Graafsma, T., Bohlmeijer, E., & de Jong, J. (2018). How WEIRD are positive psychology interventions? A bibliometric analysis of randomized controlled trials on the science of well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2018.1484941.

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J., & Norenzayan, A. (2010). The weirdest people in the world? Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33, 61–135. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0140525X0999152X.

Hernández-Torrano, D., Ibrayeva, L., Sparks, J., Lim, N., Clementi, A., Almukhambetova, A., Nurtayev, Y., & Muratkyzy, A. (2020). Mental health and well-being of university students: A bibliometric mapping of the literature. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01226.

Hicks, D., Wouters, P., Waltman, L., de Rijcke, S., & Rafols, I. (2015). Bibliometrics: The Leiden manifesto for research metrics. Nature, 520(7548), 429–431. https://doi.org/10.1038/520429a.

Hills, R. C., & Atkins, P. W. B. (2013). Cultural identity and convergence on Western attitudes and beliefs in the United Arab Emirates. International Journal of Cross Cultural Management, 13(2), 193–213. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595813485380.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations (2nd ed.) SAGE.

Hofstede Insight. (n.d.). What about the United Arab Emirates? https://www.hofstede-insights.com/country-comparison/the-united-arab-emirates/

Hortop, E. G., Wrosch, C., & Gagné, M. (2013). The why and how of goal pursuits: Effects of global autonomous motivation and perceived control on emotional well-being. Motivation and Emotion, 37(4), 675–687. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-013-9349-2.

Howell, A. J. (2009). Flourishing: Achievement-related correlates of students' wellbeing. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 4, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760802043459.

Humphrey, A., Bliuc, A.-M., & Molenberghs, P. (2020). The social contract revisited: A re-examination of the influence individualistic and collectivistic value systems have on the psychological wellbeing of young people. Journal of Youth Studies, 2, 260–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2019.1590541.

January, J., Madhombiro, M., Chipamaunga, S., Ray, S., Chingono, A., & Abas, M. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among undergraduate university students in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 7, 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0723-8.

Joshanloo, M. (2013). The influence of fear of happiness beliefs on responses to the satisfaction with life scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 54(5), 647–651. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.11.011.

Joshanloo, M., Lepshokova, Z. K., Panyusheva, T., Natalia, A., Poon, W. C., Yeung, V. W., Sundaram, S., Achoui, M., Asano, R., Igarashi, T., Tsukamoto, S., Rizwan, M., Khilji, I. A., Ferreira, M. C., Pang, J. S., Ho, L. S., Han, G., Bae, J., & Jiang, D. (2014). Cross-cultural validation of the fear of happiness scale across 14 national groups. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 45(2), 246–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022113505357.

Joshanloo, M., Weijers, D., Jiang, D.-Y., Han, G., Bae, J., Pang, J., et al. (2015). Fragility of happiness beliefs across 15 national groups. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16, 1185–1210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-014-9553-0.

Karaman, M. A., Nelson, K. M., & Cavazos Vela, J. (2018). The mediation effects of achievement motivation and locus of control between academic stress and life satisfaction in undergraduate students. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 46(4), 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1346233.

Karampas, K., Michael, G., & Stalikas, A. (2016). Positive emotions, resilience and psychosomatic health: Focus on Hellenic Army NCO cadets. Psychology, 7, 1727–1740. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2016.713162.

Kim, H., Doiron, K., Warren, M. A., & Donaldson, S. I. (2018). The international landscape of positive psychology research: A systematic review. International Journal of Wellbeing, 8(1), 50–70. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v8i1.651.

Kirkpatrick, M. A., Stant, K., & Downes, S. (2008). Perceived locus of control and academic performance: Broadening the construct’s applicability. Journal of College Student Development, 49(5), 486–496. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.0.0032.

Klug, H. J. P., & Maier, G. W. (2015). Linking goal progress and subjective well-being: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 16(1), 37–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9493-0.

Knappe, S., & Pinquart, M. (2009). Tracing criteria of successful aging? Health locus of control and well-being in older patients with internal diseases. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 14(2), 201–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548500802385717.

Krekel, C., Ward, G., & Neve, J. D. (2019). Employee wellbeing, productivity, and firm performance. Labor: Human Capital eJournal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3356581.

Kurman, J., & Sriram, N. (2002). Interrelationships among vertical and horizontal collectivism, modesty, and self-enhancement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033001005.

Lalwani, A. K., & Shavitt, S. (2013). You get what you pay for? Self-construal influences price-quality judgments. Journal of Consumer Research, 40(2), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1086/670034.

Lalwani, A. K., Shavitt, S., & Johnson, T. (2006). What is the relation between cultural orientation and socially desirable responding? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90(1), 165–178. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.165.

Lambert, L., Abdulrehman, R., & Mirza, C. (2019). Coming full circle: Taking positive psychology to GCC universities. In L. Lambert, & N. Pasha-Zaidi (Eds.), Positive psychology in the Middle East/North Africa: Research, policy, and practise (pp. 93–110). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13921-6_5.

Lambert, L., Lomas, T., van de Weijer, M. P., Passmore, H. A., Joshanloo, M., Harter, J., Ishikawa, Y., Lai, A., Kitagawa, T., Chen, D., Kawakami, T., Miyata, H., & Diener, E. (2020). Towards a greater global understanding of wellbeing: A proposal for a more inclusive measure. International Journal of Wellbeing, 10(2), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v10i2.1037.

Lambert, L., Pasha-Zaidi, N., Passmore, H.-A., & York Al-Karam, C. (2015). Developing an indigenous positive psychology in the United Arab Emirates. Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 1–23.

Lambert, L., Passmore, H.-A., & Joshanloo, M. (2019). A positive psychology intervention program in a culturally-diverse university: Boosting happiness and reducing fear. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1141–1162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9993-z.

Lambert, L., Passmore, H.-A., Scull, N., Al Sabah, I., & Hussain, R. (2019). Wellbeing matters in Kuwait: The Alnowair’s Bareec education initiative. Social Indicators Research, 143(2), 741–763. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-018-1987-z.

Layous, K., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). Positive activities as protective factors against mental health conditions. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 123, 3–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034709.

Layous, K., Kurtz, J., Chancellor, J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Reframing the ordinary: Imagining time as scarce increases well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 13, 301–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1279210.

Layous, K., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2014). The how, why, what, when, and who of happiness: Mechanisms underlying the success of positive interventions. In J. Gruber & J. Moscowitz (Eds.), Positive emotion: Integrating the light sides and dark sides (pp. 473–495). Oxford University Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199926725.003.0025.

Lee, E.-H. (2012). Review of the psychometric evidence of the perceived stress scale. Asian Nursing Research, 6(4), 121–127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anr.2012.08.004.

Lutz, P. K., & Passmore, H.–A. (2019). Repercussions of individual and societal valuing of happiness. In L. Lambert, & N. Pasha-Zaidi (Eds.), Positive psychology in the Middle East/North Africa: Research, policy, and practise (pp. 363–390). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-13921-6_16.

Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803.

Macaskill, A. (2013). The mental health of university students in the United Kingdom. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 41, 426–441. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2012.743110.

Mangan, S., Baumsteiger, R., & Bronk, K. C. (2020). Recommendations for positive psychology interventions in school settings. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 653–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789709.

McCambridge, J., Witton, J., & Elbourne, D. R. (2014). Systematic review of the Hawthorne effect: New concepts are needed to study research participation effects. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 67(3), 267–277. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.08.015.

Mehl, M. R., Vazire, S., Holleran, S. E., & Clark, C. S. (2010). Eavesdropping on happiness: Wellbeing is related to having less small talk and more substantive conversations. Psychological Science, 21(4), 539–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610362675.

Mongrain, M., & Anselmo-Matthews, T. (2012). Do positive psychology exercises work? A replication of Seligman et al. (2005). Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68, 382–338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21839.

Mongrain, M., Barnes, C., Barnhart, R., & Zalan, L. B. (2018). Acts of kindness reduce depression in individuals low on agreeableness. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 4, 323–334. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000168.

Moon, C., Travaglino, G. A., & Uskul, A. K. (2018). Social value orientation and endorsement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism: An exploratory study comparing individuals from North America and South Korea. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02262.

Moore, D. (2007). Self perceptions and social misconceptions: The implications of gender traits for locus of control and life satisfaction. Sex Roles, 56, 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9238-9.

Morrison, M., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2011). Subjective well-being and national satisfaction: Findings from a worldwide survey. Psychological Science, 22(2), 166–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797610396224.

Moskowitz, J. T., Cheung, E. O., Freedman, M., Fernando, C., Zhang, M. W., Huffman, J. C., & Addington, E. L. (2021). Measuring positive emotion outcomes in positive psychology interventions: A literature review. Emotion Review, 13(1), 60–73. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073920950811.

Nelson, M. R., & Shavitt, S. (2002). Horizontal and vertical individualism and achievement values: A multimethod examination of Denmark and the United States. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 33(5), 439–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022102033005001.

Nezlek, J. B., & Mroziński, B. (2020). Applications of multilevel modeling in psychological science: Intensive repeated measures designs. L’Année Psychologique, 120(1), 39–72. https://doi.org/10.3917/anpsy1.201.0039.

Ngamaba, K. H., & Soni, D. (2018). Are happiness and life satisfaction different across religious groups? Exploring determinants of happiness and life satisfaction. Journal of Religion and Health, 57(6), 2118–2139. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10943-017-0481-2.

Oishi, S. (2000). Goals as cornerstones of subjective well-being: Linking individuals and cultures. In E. Diener & E. M. Suh (Eds.), Culture and subjective well-being (pp. 87–112). MIT Press.

Oladipo, S. E., Adenaike, F. A., Adejumo, A. O., & Ojewumi, K. O. (2013). Psychological predictors of life satisfaction among undergraduates. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences, 82, 292–297. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.263.

Ong, A. D., Benson, L., Zautra, A. J., & Ram, N. (2018). Emodiversity and biomarkers of inflammation. Emotion, 18(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000343.

Parks, A. C., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2013). Positive interventions: Past, present, and future. In T. B. Kashdan & J. Ciarrochi (Eds.), Mindfulness, acceptance, and positive psychology: The seven foundations of well-being (pp. 140–165). New Harbinger.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (1993). Review of the satisfaction with life scale. Psychological Assessment, 5, 164–172. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.5.2.164.

Pavot, W., & Diener, E. (2008). The satisfaction with life scale and the emerging construct of life satisfaction. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 137–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760701756946.

Perna, G., Grassi, M., Caldirola, D., & Nemeroff, C. (2018). The revolution of personalized psychiatry: Will technology make it happen sooner? Psychological Medicine, 48(5), 705–713. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291717002859.

Pettit, J. W., Kline, J. P., Gencoz, T., Gencoz, F., & Joiner Jr., T. E. (2001). Are happy people healthier? The specific role of positive affect in predicting self-reported health symptoms. Journal of Research in Personality, 35(4), 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1006/jrpe.2001.2327.

Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2005). Does positive affect influence health? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 925–971. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.925.

Pressman, S. D., & Cohen, S. (2012). Positive emotion word use and longevity in famous deceased psychologists. Health Psychology, 31, 297–305. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025339.

Quevedo, R. J. M., & Abella, M. C. (2014). Does locus of control influence subjective and psychological well-being? Personality and Individual Differences, 60(Supplement), S55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.231

Rand, D. G., Kraft-Todd, G., & Gruber, J. (2015). The collective benefits of feeling good and letting go: Positive emotion and (dis) inhibition interact to predict cooperative behavior. PLoS One, 10(1), e0117426. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0117426.

Rao, M. A., Donaldson, S. I., & Doiron, K. M. (2015). Positive psychology research in the Middle East and North Africa. The Middle East Journal of Positive Psychology, 1(1), 60–76.

Rao, D., Horton, R. A., Tsang, H. W. H., Shi, K., & Corrigan, P. W. (2010). Does individualism help explain differences in employers’ stigmatizing attitudes toward disability across Chinese and American cities? Rehabilitation Psychology, 55(4), 351–359. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0021841.

Richards, M., & Huppert, F. A. (2011). Do positive children become positive adults? Evidence from a longitudinal birth cohort study. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 75–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2011.536655.

Riches, S., Schrank, B., Rashid, T., & Slade, M. (2016). WELLFOCUS PPT: Modifying positive psychotherapy for psychosis. Psychotherapy, 53(1), 68–77. https://doi.org/10.1037/pst0000013.

Riemer, H., & Shavitt, S. (2011). Impression management in survey responding: Easier for collectivists or individualists? Journal of Consumer Psychology, 21(2), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcps.2010.10.001.

Rotter, J. B. (1966). Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement. Psychological Monographs, 80, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0092976.

Ryff, C., Love, G., Urry, H., Muller, D., Rosenkranz, M., Friedman, E., Davidson, R. J., & Singer, B. (2006). Psychological well-being and ill-being: Do they have distinct or mirrored biological correlates? Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 75, 85–95. https://doi.org/10.1159/000090892.

Ryff, C., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaemonic approach to psychological wellbeing. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9, 13–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9019-0.

Schueller, S. M. (2010). Preferences for positive psychology exercises. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(3), 192–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439761003790948.

Schueller, S. (2012). Personality fit and positive interventions: Extraverted and introverted individuals benefit from different happiness increasing strategies. Psychology, 3(12A), 1166–1173. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2012.312A172.

Segerstrom, S., & Miller, G. (2004). Psychological stress and the human immune system: A meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological Bulletin, 104, 601–630. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601.

Senf, K., & Liau, A. K. (2013). The effects of positive interventions on happiness and depressive symptoms, with an examination of personality as a moderator. Journal of Happiness Studies, 14, 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-012-9344-4.

Sewilam, A. M., Watson, A. M. M., Kassem, A. M., Clifton, S., McDonald, M. C., Lipski, R., Deshpande, S., Mansour, H., & Nimgaonkar, V. L. (2015). Roadmap to reduce the stigma of mental illness in the Middle East. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(2), 111–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014537234.

Shavitt, S., & Barnes, A. J. (2020). Culture and the consumer journey. Journal of Retailing, 96(1), 40–54. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretai.2019.11.009.

Shavitt, S., Lalwani, A. K., Zhang, J., & Torelli, C. J. (2006). The horizontal/vertical distinction in cross-cultural consumer research. Journal of Consumer Psychology, 16(4), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327663jcp1604_3.

Shin, L. J., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2016). Positive activity interventions for mental health conditions: Basic research and clinical applications. In J. Johnson & A. Wood (Eds.), The handbook of positive clinical psychology (pp. 349–363). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118468197.ch23.

Singelis, T. M., Triandis, H. C., Bhawuk, D. P. S., & Gelfand, M. J. (1995). Horizontal and vertical dimensions of individualism and collectivism: A theoretical and measurement refinement. Cross-Cultural Research, 29(3), 240–275. https://doi.org/10.1177/106939719502900302.

Son, J., & Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteer work and hedonic, eudemonic, and social wellbeing. Sociological Forum, 27(3), 658–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01340.x.

Steel, P., Taras, V., Uggerslev, K., & Bosco, F. (2018). The happy culture: A theoretical, meta-analytic, and empirical review of the relationship between culture and wealth and subjective well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 22(2), 128–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868317721372.

Steele, L. G., & Lynch, S. M. (2013). The pursuit of happiness in China: Individualism, collectivism, and subjective well-being during China’s economic and social transformation. Social Indicators Research, 114(2), 441–451. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-012-0154-1.

Stockings, E. A., Degenhardt, L., Dobbins, T., Lee, Y. Y., Erskine, H. E., Whiteford, H. A., & Patton, G. (2016). Preventing depression and anxiety in young people: A review of the joint efficacy of universal, selective and indicated prevention. Psychological Medicine, 46(1), 11–26. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715001725.

Suldo, S. M., Thalji, A., & Ferron, J. (2011). Longitudinal academic outcomes predicted by early adolescents’ subjective wellbeing, psychopathology, and mental health status yielded from a dual-factor model. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 6(1), 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.536774.

Syed, A., Ali, S. S., & Khan, M. (2018). Frequency of depression, anxiety and stress among the undergraduate physiotherapy students. Pakistan journal of medical sciences, 34(2), 468–471. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.342.12298.

Taylor, C. T., Lyubomirsky, S., & Stein, M. B. (2017). Upregulating the positive affect system in anxiety and depression: Outcomes of a positive activity intervention. Anxiety and Depression, 34, 267–280. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22593.

Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6494.696169.

Triandis, H. C., & Gelfland, M. J. (1998). Converging measurement of horizontal and vertical individualism and collectivism. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74, 118–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.1.118.

Triandis, H. C., & Suh, E. M. (2002). Cultural influences on personality. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 133–160. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135200.

Trice, A. (1985). An academic locus of control scale for college students. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 61, 1043–1046. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1985.61.3f.1043.

van Assen, M. A. L. M., van Aert, R. C. M., Nuijten, M. B., & Wicherts, J. M. (2014). Why publishing everything is more effective than selective publishing of statistically significant results. PLoS One, 9(1), e84896. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084896.

Veenhoven, R. J. (2008). Healthy happiness: Effects of happiness on physical health and the consequences for preventive health care. Journal of Happiness Studies, 9(3), 449–469. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9042-1.

Verme, P. (2009). Happiness, freedom and control. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 71, 146–161. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2009.04.008.

Walsh, S., Cassidy, M., & Priebe, S. (2016). The application of positive psychotherapy in mental health care: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(6), 638–651. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22368.

Wang, X., Peng, S., Li, H., & Peng, Y. (2015). How depression stigma affects attitude toward help seeking: The mediating effect of depression somatization. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 43, 945–954. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2015.43.6.945.

Weiss, L. A., Westerhof, G. J., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2016). Can we increase psychological well-being? The effects of interventions on psychological well-being: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. PLoS One, 11(6), e0158092.

Welbourne, J. L., Gangadharan, A., & Sariol, A. M. (2015). Ethnicity and cultural values as predictors of the occurrence and impact of experienced workplace incivility. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 20(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038277.

White, M. A. (2016). Why won't it stick? Positive psychology and positive education. Psychology of Wellbeing, 6, 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-016-0039-1.

Wilkins, S. S., Bourke, P., Salam, A., Akhtar, N., D’Souza, A., Kamran, S., et al. (2018). Functional stroke mimics: Incidence and characteristics at a primary stroke center in the Middle East. Psychosomatic Medicine, 80(5), 416–421. https://doi.org/10.1097/PSY.0000000000000563.

Willemyns, M. (2008). The rapid transformation of Emirati managers' values in the United Arab Emirates. Proceedings of the Academy of World Business Marketing and Management Development. https://ro.uow.edu.au/dubaipapers/137/

Wong, P. T. P., & Roy, S. (2017). Critique of positive psychology and positive interventions. In N. J. L. Brown, T. Lomas, & F. J. Eiroa-Orosa (Eds.), The Routledge international handbook of critical positive psychology (pp. 142–160). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315659794-12.

Woodworth, R. J., O’Brien-Malone, A., Diamond, M. R., & Schüz, B. (2016). Web-based positive psychology interventions: A reexamination of effectiveness. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 73(3), 218–232. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.22328.

Wright, N. S., & Bennett, H. (2008). Harmony and participation in Arab and Western teams. Education, Business and Society: Contemporary Middle Eastern Issues, 1(4), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1108/17537980810929957.

Yakushko, O., & Blodgett, E. (2021). Negative reflections about positive psychology: On constraining the field to a focus on happiness and personal achievement. Journal of Humanistic Psychology, 61(1), 104–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022167818794551.

Ye, D., Ng, Y.-K., & Lian, Y. (2015). Culture and happiness. Social Indicators Research, 123(2), 519–547. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-014-0747-y.

Zalewska, A. M., & Zawadzka, A. (2016). Subjective well-being and citizenship dimensions according to individualism and collectivism beliefs among polish adolescents. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 4(3), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.5114/cipp.2016.61520.

Zhang, Y., & Han, B. (2016). Positive affect and mortality risk in older adults: A meta-analysis: Positive affect and mortality meta-analysis. PsyCh Journal, 5(2), 125–138. https://doi.org/10.1002/pchj.129.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Lambert, L., Warren, M.A., Schwam, . et al. Positive psychology interventions in the United Arab Emirates: boosting wellbeing – and changing culture?. Curr Psychol 42, 7475–7488 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02080-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02080-0