Abstract

Parental knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts is central for healthy adolescent development. However, parents and their adolescent children often perceive parenting practices differently. Using data from matching parent and adolescent dyads (n = 477) from the longitudinal research program LoRDIA, we investigated in what way disagreement between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental knowledge, solicitation and behavioral control and adolescent disclosure, is longitudinally related to girls’ and boys’ psychological problems (internalizing and externalizing) and well-being. The adolescents’ mean age was 13.0 years (SD = .56) at T1 and 14.30 years (SD = .61) at T2, evenly distributed between boys (52.6%) and (47.4%) girls at baseline. The discrepancy scores were calculated by subtracting the adolescent’s scores from the parent’s scores. Parent-adolescent discrepancies had somewhat different patterns of associations with boys’ and girls’ psychological problems and well-being. Parental knowledge discrepancy was related to higher levels of girls’ externalizing problems while parental solicitation discrepancy was related to higher levels of boys’ externalizing problems and lower levels of girls’ wellbeing. Adolescent disclosure discrepancy was related to higher levels of girls’ internalizing problems and lower levels of well-being. Negative concurrent associations were shown between parental control discrepancy and adolescents’ internalizing problems. Parents’ overestimating the level of parent-adolescent communication, including adolescent disclosure, and parental solicitation in particular, is disadvantageous for adolescent psychological health.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Parenting research often relies on parents’ and adolescents’ reports on different aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship, including parental knowledge of adolescents’ activities and parent-adolescent communication (i.e. parental solicitation and behavioral control, and adolescent disclosure). Such aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship are key elements in parenting that are protective of adolescent psychological adjustment (Keijsers et al. 2010; Stattin and Kerr 2000). However, parents and their adolescent children perceive their relationships differently (Guion et al. 2009), with parents often perceiving their parenting behaviors in a better light than their adolescent children do (Hou et al. 2019; Janssens et al. 2015). Differences in their perceptions of parenting may be a normative part of adolescence (Phinney et al. 2005) or stem from underlying problems in the parent-adolescent relationship (Guion et al. 2009). Parents’ and adolescents’ discrepant views of their relationships are, however, linked to disruptions in adolescent behavior or poor psychological health (De Reyes and Kazdin 2005; Guion et al. 2009; Reynolds et al. 2011). For example, parent-adolescent discrepancies in parenting behaviors such as control and discipline, are predictive of a higher incidence of internalized problems (Maurizi et al. 2012) and externalized problems (Gaylord et al. 2003) as well as poorer well-being (Stuart and Jose 2012). However, little is known about how discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parental knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts, and parent-adolescent communication are associated with psychological problems and well-being in adolescent girls and boys over time. In this study, we first investigate the discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on adolescent disclosure, parental knowledge, solicitation and behavioral control separately for boys and girls. Secondly, we test in what way disagreement between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication are longitudinally related to psychological problems (internalizing and externalizing) and well-being in separate models for adolescent boys and girls.

The Period of Early Adolescence

Early adolescence involves significant social, cognitive and emotional growth in adolescents. Although for many adolescents this period involves a number of positive developmental outcomes, early adolescence is also the period in life when externalizing problems, such as conduct problems, as well as internalizing problems, such as anxiety and depressive symptoms begin to manifest (Goodman and Goodman 2009; Meeus 2016). Although such psychological problems tend to decrease over the course of adolescence (Meeus et al. 2004; Nelemans et al. 2014), both the internalizing and externalizing of problems peek between early and middle adolescence. Findings also support a general decrease in mental well-being (e.g. life-satisfaction and purpose in life), especially among adolescent girls (Currie et al. 2012). Nevertheless, the general mental health of adolescents is often sensitive and complex and easily affected by the qualities of social relations during early adolescence. Although peers and schools are important contextual elements in adolescents’ lives, the relationship between parents and adolescents is considered to have a proximal influence on adolescent psychological health and general development (Sameroff 2010). Thus, one way to gain more understanding of adolescent development is to focus on parent-adolescent relationships.

Parenting Adolescents

Parenting style theories (Baumrind 1975; Soenens et al. 2019) suggest that a healthy parent-child relationship is central for children’s psychosocial development, including children’s psychological health. Accordingly, parents are responsible for providing appropriate guidance and promoting positive developmental outcomes for their children. One parental strategy that makes parental guidance and protection possible, is having knowledge of an adolescent’s whereabouts (Dishion and MacMahon 1998). When parents have knowledge of their adolescent children’s everyday activities, they have the possibility to impose adequate parenting techniques to promote positive developmental outcomes and protect their adolescents from harm (Kapetanovic et al. 2017; Stattin and Kerr 2000). Parents acquire such knowledge through parent-driven communication, such as solicitation (i.e. actively tracking and asking adolescents for information) and behavioral control (i.e. setting behavioral rules) or adolescent-driven communication – voluntary adolescent disclosure of activities (Stattin and Kerr 2000). When parents seek information and communicate rules of behavior to their adolescent children, parents can stay informed of their adolescent activities and provide support when needed (Dishion and McMahon 1998; Fletcher et al. 2004). Sometimes, however, such parental strategies can be perceived by adolescents as overly controlling (Kakihara and Tilton-Weaver 2009) or intrusive (Hawk et al. 2008) which could cause disruptions in the parent-adolescent relationship (Hawk et al. 2013). Moreover, when adolescents feel emotionally close to their parents (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010) they tend voluntarily to share information about their everyday activities with their parents, which gives parents the possibility to give their adolescents support and guidance without being perceived as intrusive. Although studies show support for the protective role of parent-driven communication efforts in terms of adolescent psychological health (Pinquart 2017a, 2017b), adolescent disclosure seems to be the strongest protective predictor of adolescent psychological health, including adolescent depressive symptoms (Hamza and Willoughby 2011) and the externalizing of problems (Kapetanovic et al. 2020). In other words, in order for parents to provide beneficial guidance for adolescents they need to have knowledge of adolescent whereabouts and to communicate with their adolescents. But what happens if parents and adolescents perceive the way parents have and acquire information about their adolescents’ activities differently?

Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies in Parenting Behaviors

According to the literature review above, parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication can be protective for healthy adolescent development when pursued adequately. However, parents and adolescents do not necessarily perceive their interactions in the same way, with parents generally rating their parenting behaviors more favorably than their adolescents (Guion et al. 2009; Janssens et al. 2015; Maurizi et al. 2012). There are at least three theoretical explanations for disagreement between parents and adolescents on parenting behaviors. One explanation is that such disagreement is a normative part of adolescent development (Phinney et al. 2005). Early adolescents move toward autonomy and independence from parents, which is manifested in greater differences in perceptions of family functioning and parenting behaviors. Particularly early adolescents, being at the core of the process of individuation from parents, tend to exhibit higher discordance from their parents’ reports as compared with older adolescents (Hou et al. 2019). Another explanation involves a “generational stake” hypothesis (Bengtson and Kuypers 1971), suggesting that parents and adolescents have different agendas when portraying parenting behaviors. Parents are inclined to describe their parenting behaviors as more positive because they are investing nurture and time in their relationship, while adolescents have a stake in minimizing parenting behaviors because they strive for autonomy and independence from their parents. A third explanation is that parents’ and adolescents’ discrepant views on aspects of their relationships may be a symptom of maladaptive parent-adolescent interactions and poor parent-child bonds (Guion et al. 2009; Welsh et al. 1998). When the parent-adolescent relationship is poor or conflicted, adolescents may have a hard time understanding parents’ behaviors, while parents, on the other hand, may misinterpret their adolescents’ behaviors. Thus, the discrepancy between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parenting behaviors could be the result of individual psychological processes or the manifestation of a poor parent-adolescent relationship.

Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies and Adolescent Health Outcomes

Although some discrepancies in parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions are indeed normative and not necessarily harmful for adolescent development (Phinney et al. 2005), discrepancies in parent-adolescent reporting may also be associated with poor adolescent development. For instance, disagreement between parents’ and adolescents’ ratings of parent-child relationship quality (Maurizi et al. 2012; Reidler and Swenson 2012) and discipline (Guion et al. 2009) is predictive of adolescents internalizing problems. Greater discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ ratings of positive parenting practices, such as family cohesion, autonomy granting, family identity (Ohannessian et al. 2000), warmth and reasoning (Hou et al. 2018), contribute to lower levels of adolescent well-being, achievement motivation and psychological competence (Leung and Shek 2014). In addition, the discrepant scores on parental knowledge of adolescents’ activities (Abar et al. 2015) and adolescent disclosure (Reidler and Swenson 2012) relate to higher levels of externalizing behaviors in adolescents. In sum, the empirical evidence suggests that discordance between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parenting is relevant for the psychosocial development in adolescents.

Current Study

Studies of discrepancies in parents’ and adolescents’ ratings on parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication with potential links to adolescent development are scarce. One study that in part addressed such a gap in the parenting literature found that parent-adolescent discrepancy in views on parental knowledge and behavioral control predicted higher adolescent involvement in substance use over time (Abar et al. 2015). Such findings indicate that deficiencies in parent-adolescent communication may be at the root of problematic adolescent development, and a symptom of a disrupted parent-adolescent relationship (Welsh et al. 1998). We want to expand the study of Abar et al. (2015) by studying the longitudinal associations between the parent-adolescent discrepancies in parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication and adolescent psychological health. In this study, we will investigate discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental knowledge, solicitation and behavioral control, and adolescent disclosure and the longitudinal associations to adolescents’ internalizing of problems, externalizing problems and their reported sense of well-being. Moreover, studies rarely include adolescent gender as a possible correlate or moderator of the links between parent-adolescent discrepancies and adolescent psychosocial outcomes (but see Ohannessian et al. 2000; Reidler and Swenson 2012). Even more rare are the studies where the effects of parent-adolescent discrepancies on psychological health are investigated separately for boys and girls. Effects adjusted without regard to gender show the overall effect of predictive variables on the outcome measure, but important information about possible gender-specific patterns is however lost. For that reason, separate analyses for each gender may instead be a better way to emphasize gender-specific conditions relevant to harm prevention and interventions to protect against mental health problems (Zahn-Waxler et al. 2008). Because boys and girls tend to differ in terms of their communication with parents (Kapetanovic et al. 2017) as well as in the manifestation of their psychological problems (Boson et al. 2017; Currie et al. 2012; Lundh et al. 2008; Nelemans et al. 2014), we will test the associations between discrepancies and adolescent psychological health outcomes separately for boys and girls. Addressing the unique predictive utility of parent-adolescent discrepancies in views regarding parental knowledge and parent-driven (parental solicitation and control) and adolescent-driven (adolescent disclosure) means of communication may provide important information about how parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of different mechanisms in the parent-adolescent relationship relate to adolescent psychological health. Based on the findings from earlier research, we hypothesize a) that parents will rate their parenting practices higher (i.e. more positive) than the adolescents (Guion et al. 2009; Janssens et al. 2015; Maurizi et al. 2012), particularly boys (Ohannessian et al. 2000) and b) that parent-adolescent discrepancies will have negative longitudinal associations with boys and girls psychological health (Abar et al. 2015; Gaylord et al. 2003; Guion et al. 2009). Because the psychological problems tend to manifest differently in boys and girls (e.g. Boson et al. 2017), we expect that the potential associations between discrepancies and adolescent psychological health outcomes would have different patterns for boys and girls.

Method

Participants and Procedure

This study is a part of the five-wave longitudinal program Longitudinal Research on Development in Adolescence (LoRDIA) which focuses on social, behavioral and psychological developmental trajectories from age 12–18 in a general population of adolescents. In 2013, contact was established with all schools in four small-to- medium-sized municipalities in the south-west part of Sweden that agreed to participate in the study. In a letter, translated into 32 different languages based on school registry data on parental native tongue, the parents and the adolescents were informed about the nature of the study, confidentiality, and the voluntary basis of participation. The adolescents filled in questionnaires collected by the research team in the classrooms. Mail questionnaires were sent to parents at the first data collection time point.

The present study utilized data from the first wave (referred to as T1) and the third wave (referred to as T2) in the LoRDIA research program, with parental (n = 550) and adolescent reports from T1 (n = 1378) and adolescents reports from T2 (n = 1324). For the purpose of this study, data from matching parent and child dyads at T1 (n = 477) were included. The adolescents’ mean age was 13.0 years (SD = .56) at T1 and 14.30 years (SD = .61) at T2, evenly distributed between boys (51.6%) and girls (48.4%). Out of these, n = 43 (10.1%) adolescents had another ethnicity than Swedish. The adolescent lived with both parents in 373 (78.2%) cases, while in 101 (21.2%) cases the child either lived with the mother, the father or alternated between the parents. The child lived with another caregiver than his or her parents in three cases (.6%). No objective measure on socio-economic status (SES) was used on the individual level; however, 71.2% reported their family to have similar SES as other families in their neighborhood, 7.0% reported having lower incomes, and 21.7% reported having more money than other families. The parental data included reports from mothers (n = 161), fathers (n = 92), as well as joint reports answered collaboratively by both parents (n = 224). Parental age was unavailable for the study. Of all adolescents at T1 (N = 477), 94.7% of adolescents responded in the study at T2. Attrition analyses revealed that adolescents who were retained at T2 did not significantly differ from adolescents who attrited at T2 in terms of parent-adolescent communication and adolescent psychological outcomes at the baseline.

Measures

Parental Knowledge and Parent-Adolescent Communication

Measures of parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication (Kerr and Stattin 2000) were used in both parental and adolescents’ questionnaires at T1, although questions were slightly altered in order to fit the reporter (e.g. “Do you…”; “Do your parents…”). In cases where both parents in the family replied, their responses were mean calculated and combined into one. Only parental items will be exemplified below.

Parental knowledge assessed how much parents knew about their adolescents’ whereabouts with six items such as “Do you know what your child does during their free time?” Internal consistencies in parents’/adolescents’ reports were α = .77/.65. Parental solicitation assessed to what extent parents were actively seeking information about their adolescent with six items such as “Do you ask your child to tell you about his/her friends (what they like to do and how things are in school)?” with internal consistencies in parents’/adolescents’ reports α = .69/.68. Parental behavioral control assessed to what extent adolescents were required to inform their parents of their whereabouts with five items such as “If your child has been out very late one night, do you require him or her to explain what he or she did and whom he or she has been with?” with internal consistencies in parents’/adolescents’ reports α = .78/.72. Adolescent disclosure assessed the adolescent’s voluntary disclosure to parents about their activities during school and free time with five items such as “When your child has been out in the evening, does he or she talk about what he or she has done that evening?” Internal consistencies in parents’/adolescents’ reports were α = .78/.69. Answers in all scales were given on a 5-point Likert with scores ranging between 1 (very often), 2 (quite often), 3 (now and then), 4 (seldom) and 5 (almost never), and were later reversed.

Psychological Problems

Internalizing and externalizing problems were measured at T1 and T2 through adolescents’ self-reports on the Swedish version of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-S) (Goodman and Goodman 2009; Lundh et al. 2008). The SDQ consists of 25 items and is a broadly used and validated instrument that aims to detect emotional and behavioral problems. The SDQ contains four problem subscales with five items each: hyperactivity/inattention (e.g. “I am easily distracted, I find it difficult to concentrate”), emotional symptoms (e.g. “I am often unhappy, disheartened, or tearful”), conduct problems (e.g. “I fight a lot, I can make other people do what I want”) and peer problems (e.g. “Other children or young people pick on me or bully me”). Answers are given on a 3-point Likert scale with scores ranging between 0 (not true), 1 (somewhat true), and 2 (certainly true). We used the two-factor model consisting of internalizing and externalizing which is preferably used in low-risk community samples (Goodman and Goodman 2009). The internalizing score ranged from 0 to 20 and is the sum of emotional symptoms and peer-problem scales. The externalizing score ranged from 0 to 20 and is the sum of the conduct and hyperactivity/inattention scales. Cronbach’s alphas for internalizing and externalizing problems at T1/ T2 were α = .70/.73 and α = .68/.75 respectively.

Mental well-being

Mental well-being was measured at T1 and T2 through adolescents’ self-reports on life-satisfaction and purpose and meaning in life (Boson et al. 2017). The following two questions were used: 1) “In general, how happy are you with life at the moment?” with scores ranging between 1 (very unhappy), 2 (quite unhappy), 3 (quite happy) and 4 (very happy) and 2) “I think that my life has purpose and meaning,” with scores ranging between 1 (completely disagree), 2 (partly disagree), 3 (partly agree) and 4 (completely agree). For the purpose of the present study, we summed up each participant’s responses. The mental well-being score ranged from 2 to 8 and the consistency of the scale was controlled by a split-half analysis at T1/T2 (Spearman-Brown coefficient α = .76/.75).

Statistical Analyses

First, we examined mean differences between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental knowledge, solicitation, behavioral control and adolescent disclosure using a paired sample t-test, separately for boys and girls. Effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d for an independent sample t-test and Hedges g (Hedges and Olkin 1985) for a paired sample t-test. For both Cohen’s d and Hedges g, 0.2 can be interpreted as a small effect, 0.5 a medium effect and 0.8 as a large effect. In addition, we conducted independent sample t-tests in SPSS 25 to analyze potential mean differences between genders in the outcome measures (internalizing and externalizing problems and well-being).

To obtain the discrepancy scores, for each construct, adolescents’ responses were paired with their parent’s response. Discrepancy scores between parent and adolescent reports were then calculated by subtracting the adolescent score from the parent score. A positive discrepancy score indicated that a parent responded with a higher number than did the adolescent and a negative discrepancy indicated that the adolescent responded with a higher number than did the parent. If the parent and child had the same response, the discrepancy score was 0. The means of all discrepancy scores were then calculated and used as vectors in the Structural Equation Models (SEM). Before moving on to do SEM analyses, we estimated the Pearson’s bivariate correlations between discrepancy scores of parental knowledge, solicitation, behavioral control, adolescent disclosure, T1 and T2 adolescent psychological problems (externalizing and internalizing) and well-being. In the next step, we conducted six separate SEM-models (one for each outcome and separately for gender), using AMOS 25. Goodness of fit indices are presented in Table 1. We entered the discrepant scores of parental knowledge, parental solicitation and behavioral control and adolescent disclosure as exogenous variables and psychological problems and well-being at T2 as endogenous variables in the models. The goodness of fit was determined using chi-square (χ2 > .05), Tucker Lewis index (TLI > .95), Comparative Fit Indices (CFI > .90) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .08) (Hair et al. 2010).

Results

The results from the pairwise t-test between parents’ and adolescents’ reports of parental knowledge, solicitation, behavioral control and adolescent disclosure separated by gender are presented in Table 2. The analyses showed that parents reported significantly higher levels of solicitation, behavioral control and adolescent disclosure than their adolescent children did, across gender. Parents also reported a significantly higher level of parental knowledge than their sons, while parents’ and their daughters’ reports on parental knowledge did not significantly differ. Differences in reports of parental knowledge, solicitation and adolescent disclosure were modest in size; however, the difference between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental behavioral control showed large effect sizes for both boys and girls. Our analyses on gender differences in adolescent psychological problems and well-being showed several significant results. Girls, T1/T2 M (SD) = 4.90 (3.19) / 5.81 (3.25), reported higher rates of internalizing problems than boys, T1/T2 M (SD) = 3.97 (2.90) / 3.61 (2.81) at both time points T1: t(1,470) = 3.30, p = .001, Cohen’s d = 0.30 and T2: t(1,385) = 7.07, p = .000, Cohen’s d = 0.72. Boys reported a higher level of externalizing problems T1/T2 M (SD) = 5.72 (3.04) / 5.33 (3.54), than girls, T1/T2 M (SD) = 4.92 (2.76) / 4.74 (3.01) at T1: t (1,309) = 3.03, p = .003, Cohen’s d = 0.28. No significant difference in externalizing problems emerged at T2. Although no gender differences on well-being emerged at T1, boys M (SD) = 3.64 (1.34) reported higher well-being at T2: t(1,350) = 2.07, p = .039, Cohen’s d = 0.22 than girls, M (SD) = 3.34 (1.36) .

Further, bivariate correlations between discrepant scores regarding parental knowledge, solicitation, and behavioral control and adolescent disclosure and adolescent psychological health outcomes (externalizing and internalizing problems and well-being) showed somewhat different patterns for girls and boys. As shown in Table 3, parental knowledge discrepancy and adolescent disclosure discrepancy were related to higher levels of girls’ internalizing and externalizing problems at both T1 and T2. Parental behavioral control discrepancy was related to lower levels of internalizing problems at T1 only. Parental solicitation discrepancy along with adolescent disclosure discrepancy were related to lower levels of well-being at T2 only for girls. As indicated in Table 4, parental knowledge discrepancy and adolescent disclosure discrepancy were related to higher levels of boys’ externalizing problems at both T1 and T2. Parental behavioral control discrepancy was related to lower levels of boys’ internalizing problems at both T1 and T2.

The Links between Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies and Adolescent Psychological Problems and Well-Being

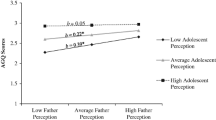

The links between parent-adolescent discrepancies and girls’ psychological outcomes are presented in Fig. 1. Internalizing and externalizing problems and well-being were moderately stable over time. Longitudinal positive links were found from parental knowledge discrepancy to externalizing problems (β = .19 p < .001) at T2, as well as from adolescent disclosure to internalizing problems (β = .22 p < .001) at T2. Negative longitudinal links were found from parental solicitation discrepancy (β = −.13 p < .05) and adolescent disclosure discrepancy (β = −.17 p < .05) to well-being at T2. In addition, positive associations were found between parental knowledge discrepancy and girls’ internalizing (β = .16 p < .05) and externalizing problems (β = .15 p < .05) at T1. Negative association was found between parental control discrepancy and girls’ internalizing problems (β = −.13 p < .05) at T1.

Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Associations from Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies on Parental Knowledge, Solicitation and Behavioral Control and Adolescent Disclosure to Adolescent Girls’ Psychological Problems and Well-being over Time Note: The results from three separate models are depicted in the Figure * p < .05 ** p < .001.

The links between parent-adolescent discrepancies and boys’ psychological outcomes are presented in Fig. 2. Also, in boys’ models, internalizing, externalizing and well-being were moderately stable over time. Only one longitudinal path was significant, showing that parental solicitation discrepancy was positively linked to boys’ externalizing problems (β = .12 p < .05) at T2. Moreover, the results showed positive associations between parental knowledge discrepancy and boys’ externalizing problems (β = .18 p < .05) at T1 as well as adolescent disclosure discrepancy and boys’ externalizing problems (β = .17 p < .05) at T1. Negative association was found between parental control discrepancy and boys’ internalizing problems (β = −.22 p < .001) at T1.

Standardized Parameter Estimates for the Associations from Parent-Adolescent Discrepancies on Parental Knowledge, Solicitation and Behavioral Control and Adolescent Disclosure to Boys’ Psychological Problems and Well-being over Time Note: The results from three separate models are depicted in the Figure * p < .05 ** p < .001.

Discussion

A growing body of literature indicates that parents and adolescents often hold discrepant views of different aspects of their relationships, such as family functioning or parental knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts. Having discrepant views on aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship may be a normative part in adolescent development. It may, however, also be a sign of something deeper, such as poor parent-adolescent relationship quality, which in turn has a negative effect on adolescent health. In this study we tested to see in what way parent-adolescent discrepancies between parental knowledge of adolescent whereabouts, parental solicitation, behavioral control and adolescent disclosure, relate to adolescents’ psychological problems (internalizing and externalizing) and well-being over time. Because parent-adolescent communication (Kapetanovic et al. 2017) and adolescent psychological functioning (Boson et al. 2017) may differ across gender, we tested these potential links separately for boys and girls. The results show that parents seem to overestimate their own and adolescent-driven communication efforts. This is particularly true for the parents of boys. Moreover, we found positive longitudinal links from parental knowledge discrepancy to externalizing problems, and from adolescent disclosure discrepancy to internalizing problems in girls. Adolescent disclosure discrepancy and parental solicitation discrepancy were also linked to lower levels of girls’ well-being over time. For boys, parental solicitation discrepancy was longitudinally and positively related to externalizing problems. Thus, discrepancies in parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication seem to be linked to poorer adolescent psychological outcomes, even though the problems manifest in somewhat different ways for boys and girls.

Corroborating the results from earlier studies (Abar et al. 2015; Janssens et al. 2015) we found that parents reported their parenting behaviors more favorably than their adolescent children. Parents could be subjected to the norms of being a “good parent,” with responsivity, boundary setting, and firm control as the golden standard of parenting (Baumrind 1975; Soenens et al. 2019). In addition, and as suggested by the “generational stake” hypothesis (Bengtson and Kuypers 1971), while adolescents search for self-identity and autonomy from parents, parents desire to maintain a sense of continuity in the relationship with their children. For that reason, parents could perceive their knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts as well as communication with adolescents in a better light than their adolescents do. Although parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental solicitation and adolescent disclosure showed small to medium discrepancies, we found that discrepancies between parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parental behavioral control (parents requiring adolescents to tell them where they go and what they do during their spare time) were large. This could indicate that parents and adolescents perceive and interpret questions about parental behavioral control differently. Since parental behavioral control may be related to feelings of being overly controlled (Kakihara and Tilton-Weaver 2009; Kapetanovic et al. 2017), adolescents could be interpreting questions about behavior control as relating to their parents depriving them of autonomy, while parents could interpret these questions as relating to a means of healthy parenting (Baumrind 1975; Soenens et al. 2019). In other words, depending on whether the reporter is the parent or the adolescent, the meaning behind their reports may be different because they perceive parenting behaviors differently. One interesting finding, however, was that parents and their daughters, in contrast to parents and their sons, seem to show more congruent views on how much parents know about their adolescent’s whereabouts. One explanation could be that girls, more than boys, believe that their parents have the right to know what they do and where they spend their time, as suggested by Smetana and Rote (2015). Although more research is needed to understand differences and similarities in parents’ and adolescents’ views on parenting practices across gender, these findings call for greater attention to parents’ and adolescents’ interpretations of parenting behaviors when providing recommendations to parents.

Understanding the link between parent-adolescent discrepancies and aspects of adolescent psychological health is not simple. The discrepant views regarding aspects of the parent-adolescent relationship can manifest in problematic health outcomes if the discrepancy conceals an underlying problem in parent-adolescent interaction (Guion et al. 2009; Welsh et al. 1998). Indeed, we found that parental knowledge discrepancy was linked to higher levels of girls’ externalizing problems over time. Parental knowledge of adolescents’ whereabouts is one of the key parenting mechanisms that is protective of adolescents externalizing behaviors (Racz and McMahon 2011). However, if parents perceive that they are more informed than what their adolescents report, parents could become more relaxed in their parenting and fail to spot potential problems in their adolescents’ lives. As a result, parents would have fewer opportunities to provide guidance and support for their adolescents, which, in turn, could potentially be harmful for adolescents’ psychological outcomes. Although the concurrent links between parental knowledge discrepancy and adolescent externalizing problems were significant for both boys and girls, the negative effect of parental knowledge discrepancy (i.e. parents rating their parental knowledge higher than their adolescents do) on adolescent externalizing problems remains two years later in girls. This is interesting given that the reports of parental knowledge generally do not differ between adolescent girls and their parents. It seems that when they do disagree about how much parents know about their adolescents’ whereabouts, such disagreement may be unfavorable for girls’ psychological health.

We found that discrepant views regarding parent-adolescent communication were related to poorer psychological health in both boys and girls, although the patterns of the links were somewhat different. While parents reporting soliciting information from their adolescents to a higher extent than their adolescents did was linked to higher levels of externalizing problems in boys, it was linked to lower well-being in girls over time. In addition, adolescent disclosure discrepancy – parents reporting that their adolescents disclosed information about their whereabouts to higher extent than their adolescents did – was linked to higher levels of internalizing and lower levels of well-being in girls over time. One explanation to differing patterns in boys and in girls is that psychological problems manifest differently in boys and girls, with boys exhibiting more externalizing problems, while girls exhibit more internalizing problems, particularly during adolescence as shown in our study as well as in earlier research (Boson et al. 2017; Currie et al. 2012). Another explanation concerns the concurrent associations between parent-adolescent discrepancies and boys’ and girls’ psychological health. Indeed, the correlation analyses showed that parent-adolescent discrepancies were associated with adolescent psychological health, showing somewhat similar patterns for boys and girls as in the longitudinal analyses. In line with Kiesner et al. (2009), parent-adolescent discrepancies may have an effect on psychological health next year because it had an effect on it now. A third explanation is that parents engage differently with boys and girls which may play an important role for their children’s psychological development (Leaper and Farkas 2015). While parents tend to encourage more emotionally close relationships with their girls, boys are allowed to be more self-assertive (Borawski et al. 2003). As adolescent disclosure is linked to emotional connectedness between parents and their children (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010) and as parental solicitation and adolescent disclosure are considered intertwined aspects of parent-adolescent communication (Kapetanovic et al. 2019; Keijsers et al. 2010), the disruptions in parent-adolescent communication may result in boys turning their problems outward and girls turning their problems inward. Mutual communication between parents and their adolescents indeed helps parents and their adolescents to stay emotionally connected to each other (Tilton-Weaver et al. 2010). When parents and adolescents have strong bonds, adolescents could be more likely to seek support, and parents would have opportunities to provide support to help their adolescents to develop self-regulating strategies in order to cope with distress. However, if parents perceive having more active and open communication with their adolescents than what their adolescents perceive they have, that may potentially be symptomatic of problems in the parent-adolescent relationship and bonds (Welsh et al. 1998). When such problems exist, parents are less likely to be asked for help or to give support and guidance their adolescents need. As a consequence of such disruptions in the parent-adolescent relationship and communication, adolescents may have a hard time finding coping strategies and therefore experience poor psychological health.

One unexpected finding was that the parental behavioral control discrepancy was related to lower levels of adolescents’ internalizing problems. Thus, when parents report having more rules and demands regarding behaviors than what their adolescent child report, adolescents report lower internalizing problems both concurrently and over time. This is particularly true for boys. The discrepancy in parent and adolescent views of their relationship could be particularly accentuated during early adolescence as part of a normal developmental trajectory (Phinney et al. 2005). One explanation may be that adolescents perceive their parents granting them autonomy and privacy even though parents perceive being in control of their adolescents’ whereabouts. The combination of parents’ sense of being in control in their parent-adolescent relationships, and non-violation of adolescent autonomy granting could be a sign of a parent-adolescent goodness-of-fit (Eccles et al. 1993). A match between parents’ demands and the adolescent’s developmental needs is, in turn, linked to higher levels of adolescent psychological functioning.

Limitations and Recommendations

Our study has some limitations. Even though mothers’ and fathers’ practices may differ (Waizenhofer et al. 2004) and their effect on adolescent health may vary in our study, we did not investigate discrepancies between mother-father and daughter-son dyads. In adolescents’ reports, the measures of parental knowledge and parent-adolescent communication did not distinguish between the parenting of mothers and of fathers. Parents, in addition, were given the opportunity to fill out the questionnaire together, which complicated any chances of analyzing the data separately for mothers and fathers. It was, however, deemed necessary in order to acquire responses from more families. Future studies should endeavor more even distribution of mothers and fathers as well as separating mothers’ from fathers’ parenting practices in order to be able to distinguish to whom the findings apply. In addition, a large group of adolescents whose parents did not participate in the LoRDIA study were excluded from the sample. This could have an impact on the external validity of the results. Although parent and adolescent interactions are bidirectional (Sameroff 2010) because of the cross-sectional characteristics of parental data we could only test unidirectional links between parent-adolescent discrepancies and adolescent psychological health. Finally, we did not control for the effects of ethnicity, SES, or family intactness on adolescent psychological outcomes. Future studies should however consider these variables when studying parent-adolescent discrepancies and their effects on adolescent psychosocial development (Hou et al. 2019).

Our findings provide evidence that parent-adolescent reporting discrepancies provide unique and valuable information on how we can understand the development of adolescent psychological health. Discrepant views on parental knowledge, and parental solicitation and adolescent disclosure in particular, relate to poorer psychological health and a lower sense of well-being in adolescents over time. Practitioners working with families need to consider the informant’s perceptions of their parent-adolescent relationships and interactions in terms of understanding adolescent psychological functioning. Above all, more attention to parents’ and adolescents’ perceptions of parent-driven communication such as asking questions, and adolescent-driven communication efforts, such as the level of information sharing, is warranted. This may be particularly important during the period of early adolescence when adolescent autonomy grows and the parent-adolescent relationship changes.

References

Abar, C. C., Jackson, K. M., Colby, S. M., & Barnett, N. P. (2015). Parent–child discrepancies in reports of parental monitoring and their relationship to adolescent alcohol-related behaviors. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 44, 1688–1701. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-014-0143-6.

Baumrind, D. (1975). The contributions of the family to the development of competence in children. Schizophrenia Bulletin, 1, 12–37. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/1.14.12.

Bengtson, V. L., & Kuypers, J. A. (1971). Generational difference and the developmental stake. Aging and Human Development, 2, 249–260. https://doi.org/10.2190/AG.2.4.b.

Borawski, E. A., Ievers-Landis, C. E., Lovegreen, L. D., & Trapl, E. S. (2003). Parental monitoring, negotiated unsupervised time, and parental trust: The role of perceived parenting practices in adolescent health risk behaviors. Journal of Adolescent Health, 33, 60–70. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1054-139X(03)00100-9.

Boson, K., Berglund, K., Wennberg, P., & Fahlke, C. (2017). Well-being, mental health problems, and alcohol experiences among young Swedish adolescents: A general population study. Journal for Person-Oriented Research, 2, 123–134. https://doi.org/10.17505/jpor.2016.12.

Currie, C., Zanotti, C., Morgan, A., Currie, D., De Looze, M., Roberts, C., & Barnekow, V. (2012). Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-Aged Children (HBSC) Study: International Report from The 2009/2010 survey.

De Reyes, A. L., & Kazdin, A. E. (2005). Informant discrepancies in the assessment of childhood psychopathology: A critical review, theoretical framework, and recommendations for further study. Psychological Bulletin, 131, 483–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.131.4.483.

Dishion, T. J., & McMahon, R. J. (1998). Parental monitoring and the prevention of child and adolescent problem behavior: A conceptual and empirical formulation. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 1, 61–75. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1021800432380.pdf.

Eccles, J, S., Midgley, C., Wigfield, A., Buchanan, C, M., Reuman, D., Flanagan, C., & Mac Iver, D. (1993). Development during Adolescence: The Impact of Stage-Environment Fit on Young Adolescents’ Experiences in Schools and in Families. American Psychologist, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.2.90

Fletcher, A. C., Steinberg, L., & Williams‐Wheeler, M. (2004). Parental influences on adolescent problem behavior: Revisiting Stattin and Kerr. Child Development, 75 (3), 781–796. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00706.x.

Gaylord, N, K., Kitzmann, K, M., & Coleman, J, K. (2003). Parents’ and children's perceptions of parental behavior: Associations with children's psychosocial adjustment in the classroom. Parenting: Science and Practice, https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327922PAR0301.

Goodman, A., & Goodman, R. (2009). Strengths and difficulties questionnaire as a dimensional measure of child mental health. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 48, 400–403. https://doi.org/10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181985068.

Guion, K., Mrug, S., & Windle, M. (2009). Predictive value of informant discrepancies in reports of parenting: Relations to early adolescents’ adjustment. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 37, 17–30. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-008-9253-5.

Hair, J, F., Black, W, C, W, C., Babin, B, J., Anderson, R, E., Babin, B, J., & Black, W, C, W, C. (2010). SEM: An introduction. multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Prentice Hall Upper Saddle River, NJ.

Hamza, C. A., & Willoughby, T. (2011). Perceived parental monitoring, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent depressive symptoms: A longitudinal examination. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 40, 902–915. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-010-9604-8.

Hawk, S. T., Hale, W. W., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., & Meeus, W. (2008). Adolescents’ perceptions of privacy invasion in reaction to parental solicitation and control. Journal of Early Adolescence, 28, 583–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/0272431608317611.

Hawk, S. T., Keijsers, L., Frijns, T., Hale, W. W., Branje, S., & Meeus, W. (2013). “I still haven’t found what i’m looking for”: Parental privacy invasion predicts reduced parental knowledge. Developmental Psychology, 49, 1286–1298. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0029484.

Hedges, LV., Olkin, I. (1985). Statistical methods for meta-analysis. New York, Academic Press

Hou, Y., Kim, S. Y., & Benner, A. D. (2018). Parent–adolescent discrepancies in reports of parenting and adolescent outcomes in Mexican immigrant families. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 47, 430–444. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-017-0717-1.

Hou, Y., Benner, A. D., Kim, S. Y., Chen, S., Spitz, S., Shi, Y., & Beretvas, T. (2019). Discordance in parents’ and adolescents’ reports of parenting: A meta-analysis and qualitative review. American Psychologist, 75, 329–348. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000463.

Janssens, A., Goossens, L., Van Den Noortgate, W., Colpin, H., Verschueren, K., & Van Leeuwen, K. (2015). Parents’ and adolescents’ perspectives on Parenting: Evaluating Conceptual Structure, Measurement Invariance, and Criterion Validity. In Assessment. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191114550477.

Kakihara, F., & Tilton-Weaver, L. (2009). Adolescents’ interpretations of parental control: Differentiated by domain and types of control. Child Development, 80, 1722–1738. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01364.x.

Kapetanovic, S., Bohlin, M., Skoog, T., & Gerdner, A. (2017). Structural relations between sources of parental knowledge, feelings of being overly controlled and risk behaviors in early adolescence. Journal of Family Studies, 26, 226–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2017.1367713.

Kapetanovic, S., Boele, S., & Skoog, T. (2019). Parent-adolescent communication and adolescent Delinquency: Unraveling Within-Family Processes from Between-Family Differences. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01043-w

Kapetanovic, S., Rothenberg, W. A., Lansford, J. E., Bornstein, M. H., Chang, L., Deater-Deckard, K., et al. (2020). Cross-cultural examination of links between parent–adolescent communication and adolescent psychological problems in 12 cultural groups. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 1225–1244. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01212-2.

Keijsers, L., Branje, S. J. T., VanderValk, I. E., & Meeus, W. (2010). Reciprocal effects between parental solicitation, parental control, adolescent disclosure, and adolescent delinquency. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 20, 88–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2009.00631.x.

Kerr, M., & Stattin, H. (2000). What parents know, how they know it, and several forms of adolescent adjustment: Further support for a reinterpretation of monitoring. Developmental Psychology, 36, 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.36.3.366.

Kiesner, J., Dishion, T. J., Poulin, F., & Pastore, M. (2009). Temporal dynamics linking aspects of parent monitoring with early adolescent antisocial behavior. Social Development, 18, 765–784. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9507.2008.00525.x.

Leaper, C., & Farkas, T. (2015). The socialization of gender during childhood and adolescence. In Handbook of socialization: Theory and research, 2nd ed. (Pp. 541–565). Guilford Press.

Leung, J. T. Y., & Shek, D. T. L. (2014). Parent-adolescent discrepancies in perceived parenting characteristics and adolescent developmental outcomes in poor Chinese families. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 23, 200–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-013-9775-5.

Lundh, L., Wångby-Lundh, M., & Bjärehed, J. (2008). Self-reported emotional and behavioral problems in swedish 14 to 15-year-old adolescents: A study with the self-report version of the strengths and difficulties questionnaire. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 49, 523–532. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2008.00668.x.

Maurizi, L. K., Gershoff, E. T., & Aber, J. L. (2012). Item-level discordance in parent and adolescent reports of parenting behavior and its implications for adolescents’ mental health and relationships with their parents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 41, 1035–1052. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-011-9741-8.

Meeus, W. (2016). Adolescent psychosocial development: A review of longitudinal models and research. Developmental Psychology, 52, 1969–1993. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000243.

Meeus, W., Branje, S., & Overbeek, G. J. (2004). Parents and partners in crime: A six-year longitudinal study on changes in supportive relationships and delinquency in adolescence and young adulthood. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 45, 1288–1298. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00312.x.

Nelemans, S. A., Hale, W. W., Branje, S. J. T., Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., Frijns, T., Van Lier, P. A. C., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2014). Heterogeneity in development of adolescent anxiety disorder symptoms in an 8-year longitudinal community study. Development and Psychopathology, 26, 181–202. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579413000503.

Ohannessian, C. M. C., Lerner, J. V., Lerner, R. M., & Von Eye, A. (2000). Adolescent-parent discrepancies in perceptions of family functioning and early adolescent self-competence. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 24, 362–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250050118358.

Phinney, J. S., Kim-Jo, T., Osorio, S., & Vilhjalmsdottir, P. (2005). Autonomy and relatedness in adolescent-parent disagreements: Ethnic and developmental factors. Journal of Adolescent Research, 20, 8–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558404271237.

Pinquart, M. (2017a). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53, 873–932. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000295.

Pinquart, M. (2017b). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with internalizing symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Marriage & Family Review, 53, 613–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2016.1247761.

Racz, S. J., & McMahon, R. J. (2011). The relationship between parental knowledge and monitoring and child and adolescent conduct problems: A 10-year update. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 14, 377–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0099-y.

Reidler, E, B., & Swenson, L, P. (2012). Discrepancies between youth and mothers’ perceptions of their mother-child relationship quality and Self-Disclosure: Implications for Youth- and Mother-Reported Youth Adjustment. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-012-9773-8

Reynolds, E. K., MacPherson, L., Matusiewicz, A. K., Schreiber, W. M., & Lejuez, C. W. (2011). Discrepancy between mother and child reports of parental knowledge and the relation to risk behavior engagement. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 40, 67–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2011.533406.

Sameroff, A. (2010). A unified theory of development: A dialectic integration of nature and nurture. Child Development, 81, 6–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01378.x.

Smetana, J. G., & Rote, W. M. (2015). What do mothers want to know about teens’ activities? Levels, trajectories, and correlates. Journal of Adolescence, 38, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.10.006.

Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., & Beyers, W. (2019). Parenting adolescents. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting: Children and Parenting (3rd ed.), (1), 101–167. New York: Routledge.

Stattin, H., & Kerr, M. (2000). Parental monitoring: a reinterpretation. child development,. Child Development, https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00210

Stuart, J., & Jose, P. E. (2012). The influence of discrepancies between adolescent and parent ratings of family dynamics on the well-being of adolescents. Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 858–868. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030056.

Tilton-Weaver, L., Kerr, M., Pakalniskeine, V., Tokic, A., Salihovic, S., & Stattin, H. (2010). Open up or close down: How do parental reactions affect youth information management? Journal of Adolescence, 33, 333–346. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.07.011.

Waizenhofer, R. N., Buchanan, C. M., & Jackson-Newsom, J. (2004). Mothers’ and fathers’ knowledge of adolescents’ daily activities: Its sources and its links with adolescent adjustment. Journal of Family Psychology, 18, 348–360. https://doi.org/10.1037/0893-3200.18.2.348.

Welsh, D. P., Galliher, R. V., & Powers, S. I. (1998). Divergent realities and perceived inequalities: Adolescents’, mothers’, and observers’ perceptions of family interactions and adolescent psychological functioning. Journal of Adolescent Research, 13, 377–402. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743554898134002.

Zahn-Waxler, C., Shirtcliff, E. A., & Marceau, K. (2008). Disorders of childhood and adolescence: Gender and psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 4, 275–303.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University West. This work was supported by the Swedish Research Council (VR); Swedish Research Council for Health, Working Life and Welfare (FORTE); Sweden’s Innovation Agency (VINNOVA); and The Swedish Research Council Formas under a combined grand (No. 259–2012-25).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Both authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by Kapetanovic Sabina and Boson Karin. Both authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

All procedures performed in the study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the institutional and/or national research committee (The Regional Research Ethics Board in Gothenburg 2013-09-25 (No. T362–13); 2014-05-20 (No. T446–14); 2015-07-31 (No. T553–15)) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Kapetanovic, S., Boson, K. Discrepancies in parents’ and adolescents’ reports on parent-adolescent communication and associations to adolescents’ psychological health. Curr Psychol 41, 4259–4270 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00911-0

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00911-0