Abstract

Does regulation impede or facilitate immigrant participation in the labor market? To answer this question, we focus on the growing and increasingly regulated Canadian health-care sector. On the one hand, occupational regulation may facilitate immigrant entry into the labor market as it imposes standards based on credentials, and recent immigrants tend to be highly skilled. On the other hand, regulatory standards are often enforced by provincially designated authorities whose selection criterion may unwittingly penalize those with foreign credentials or experience. Using a longitudinal data set combining information on the regulation of nine Canadian health-care occupations and the Canadian Census from 1991 to 2006, we test whether the introduction of regulation places a greater burden on the immigrant population relative to the native-born. Specifically, we employ a difference in methodology, exploiting variation across provinces and over time in whether an occupation is regulated to identify its effect on the ratio of immigrants-to-native-born workers employed in that occupation. The results indicate that, on average, a province’s introduction of occupational regulation increases the participation of immigrants relative to the native-born by 20 %.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

See Bilgel and Tran (2013) for a recent analysis of health expenditures in Canada.

The occupations studied by Law and Marks (2009) are accountants, barbers, beauticians, engineers, midwives, pharmacists, plumbers, practical nurses, and registered nurses.

Note that the results reported by Law and Marks (2009) are not marginal effects but the point estimates on the coefficients of interest.

We do not study the territories, as there would be too few immigrants to construct our measures for each of the occupations under study.

A word of caution on this last remark, some provinces require application for regulation by a professional association, and so our estimator could be influenced by any excluded variables that affect regulation applications and the ratio of immigrants to native-born in an occupation. For example, this could be the case if there were concerns of the public about the credentials or foreign-trained professionals.

Some of the occupations listed below are included in scope of practice legislation, but not all.

The criteria for provincial eligibility for Canada Health Transfers requires that health insurance be provided in a way such that it is publicly administrated, comprehensive, universal, portable, and accessible (Canada Health Act (1985)).

It is worth noting that Oreopoulos et al. (2012) find evidence that Canadian graduates experience a significant and persistent effect of graduating in a recession on wages; however, the effect on labor force participation disappears after 3 years.

The other sufficient condition is that the matrix of control variables if of full rank.

Confidentiality requirements prevent us from identifying the missing province-occupations pairs.

The authors have requested additional data from Statistics Canada from the 1981 and 1986 censuses to obtain more observations for our analysis. With these new data, we would expand the scope of variation in regulation to include an additional 17 regulatory changes while we currently are working with 27. This would also increase the number of observations by 180.

Auxiliary regression analysis was conducted to examine the effect of regulation on total employment, and no statistical relationship was present in the data. We have not presented these results, as the absence of adequate control variables is more of a concern with employment in an occupation as a dependent variable than the ratio of employment for two sub-populations.

References

Aydemir, A. (2003). Effects of business cycles on the labour market assimilation of immigrants. In Charles Beach and Alan Green (Ed.), Canadian Immigration Policy for the 21st Century. Kingston: Queen’s University.

Aydemir, A., & Skuterud, M. (2005). Explaining the deteriorating entry earnings of Canada's immigrant cohorts, 1966–2000. Canadian Journal of Economics, 38(2), 641–672.

Barth, E., Bratsberg, B., & Raaum, O. (2004). Identifying earnings assimilation of immigrants under changing macroeconomic conditions. The Scandinavian Journal of Economics, 106(1), 1–22.

Besley, T., & Burgess, R. (2004). Can labor regulation hinder economic performance? Evidence from India. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 119(1), 91–134.

Bilgel, F., & Tran, K. C. (2013). The determinants of Canadian provincial health expenditures: evidence from a dynamic panel. Applied Economics, 45(2), 201–212.

Canadian Institute for Health Information (2008). Canada's health care providers, 1997 to 1996: a reference guide. Ottawa, Ont:CIHI.

Carrasco, R., & Garcia Perez, J. I. (2012). Economic conditions and employment dynamics of immigrants versus natives: who pays the costs of the “great recession”? University Carlos III De Madrid Working Paper Economics Series 12-32.

Chiswick, B. R., Lee, Y. L., & Miller, P. W. (2005). A longitudinal analysis of immigrant occupational mobility: a test of the immigrant assimilation hypothesis. International Migration Review, 39(2), 332–353.

Evans, R. W. (1983). Health care in Canada. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law, 8(1), 1–43.

Federman, M. N., Harrington, D. E., & Krynski, K. J. (2006). The impact of state licensing regulations on low-skilled immigrants: the case of Vietnamese manicurists. American Economic Review, 96(2), 237–241.

Ferrer, A., & Riddell, C. W. (2008). Education, credentials, and immigrant earnings. Canadian Journal of Economics, 41(1), 186–216.

Friedman, M., & Kuznets, S. (1945). Income from independent professional practice. New York: National Bureau of Economic Research.

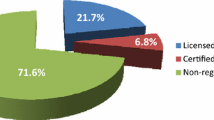

Girard, M., & Smith, M. (2012). Working in a regulated occupation in Canada: an immigrant native-born comparison. Journal of International Migration and Integration. doi:10.1007/s12134-012-0237-5.

Government of Canada. Working in Canada. http://www.workingincanada.gc.ca/home-eng.do?lang=eng

Government of Canada. National Occupational Classification 2006. http://www30.hrsdc.gc.ca/NOC/English/NOC/2006/Welcome.aspx

Green, D. A. (1999). Immigrant occupational attainment: assimilation and mobility over time. Journal of Labor Economics, 17(1), 49–79.

Hou, F., & Picot, G. (2014). Annual levels of immigration and immigrant entry earnings in Canada. Canadian Public Policy 40(2)

Human Resources and Skills Development Canada National Occupation Classification (2011). http://www5.hrsdc.gc.ca/noc/english/noc/2011/Welcome.aspx. accessed: 21 May 2014.

Kleiner, M. M., & Krueger, R. T. (2010). Analyzing the extent and influence of occupational licensing on the labor market. Journal of Labor Economics, 31(2), S173–S202.

Law, M. T., & Marks, M. S. (2009). Effects of occupational licensing laws on minorities: evidence from the progressive era. Journal of Law and Economics, 52(2), 351–366.

Muzondo, T. R., & Pazderka, B. (1980). Occupational licensing and professional incomes in Canada. Canadian Journal of Economics, 13(4), 659–667.

Oreopoulos, P. (2011). Why do skilled immigrants struggle in the labor market? A field experiment with thirteen thousand resumes. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3, 148–171.

Smith, A. (1937). The Wealth of Nations. New York: Modern Library. (Originally published 1776).

Stigler, G. (1971). The theory of economic regulation. Bell Journal of Economics, 2, 3–21.

Zietsma, D. (2010). Immigrants working in regulated occupations. Perspectives 13–28. Retrieved from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/pub/75-001-x/2010102/pdf/11121-eng.pdf. Accessed 20 March 2012.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Fu, C., Hickey, R. The Costs of Regulatory Federalism: Does Provincial Labor Market Regulation Impede the Integration of Canadian Immigrants?. Int. Migration & Integration 16, 987–1002 (2015). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0394-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12134-014-0394-9