Abstract

This study explores the connection between relationship duration and feelings of closeness in Norwegian men and women, and the association with sexual satisfaction and activity. A sample of 4160 Norwegians aged 18–89 years was enrolled from a randomly selected web panel of 11,685 Norwegians. This study focused on participants who were married or cohabiting (1432 men, 1207 women). Closeness was the highest for men and women who had been with their partner for 0−6 years. However, among those who had been with their partner for 31 years or longer, men felt closer to their partners than women. Irrespective of relationship duration, the most important factor for both men and women’s perceived closeness with their partner was general sexual satisfaction. Among men who had lived with their partner for 7−20 years and 31 years or longer, having been monogamous in life was significantly associated with “inclusion of others in the self” (IOS). Further, closeness was associated with higher intercourse frequency, lower masturbation frequency, and satisfaction with genital appearance in men who had been with their partners for 31 years or more. Intercourse frequency was significantly associated with IOS in women who had been with their partner for 0−6 years. Furthermore, in women who had been with their partner for 31 years or more, satisfaction with their own weight was important for IOS. In conclusion, men and women reported similar degrees and patterns of IOS up to the point where they had been in their relationship for more than 30 years. Thereafter, women reported feeling less close to their partners, while men’s feelings of closeness increased. This may be related to physiological, psychological, and social changes in the lives of aging men and women.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

This study aims to describe the feeling of closeness with a married or cohabiting partner in relation to the duration of the relationship among Norwegian adults. In most studies on the degree of closeness in couple relationships, the duration of the relationship is treated as a continuous variable and a linear relationship between the two variables is estimated. Nevertheless, this link is not simple, and many clinical observations point to a different pattern. A popular belief is for instance that there exists a 7-year crisis in couple relationships, where the partners are starting to feel less close. However, the feeling of closeness may vary with time and challenges. In addition to examine variations in the feeling of closeness with the length of the relationship, a second aim was to explore how these factors were related to sexual activity, satisfaction, non-monogamous experience, and body image.

Closeness to the Partner–“Inclusion of Others in the Self”

The theoretical framework for the study rests on the work of Aron et al. (1992) on feelings of closeness to the partner. According to Aron et al. (1992), feelings of closeness can be seen as overlapping selves, which seems consistent with several previous approaches to closeness between individuals in the social psychology field. Aron et al. (1992) developed a concept called “Inclusion of others in the self” (IOS) to tap people’s sense of interpersonal interconnectedness. Aron et al. (1992, p. 598) states that: “The IOS Scale is hypothesized to tap people's sense of being interconnected with another. That sense may arise from all sorts of processes, conscious or unconscious, and including the other in the self may or may not be one of these processes. The IOS Scale is intended to capture something in the respondent's perception of a relationship that is consistent with many theoretical orientations. IOS rests on self-expansion theory which defines relationship closeness as the degree to which an individual expands his or her own cognitive construct of the self by the cognitive construct of the relationship partner’s self (Aron et al., 2004; Pietras & Briken, 2021), which is why the couple adopts a "we-perspective". The IOS scale incorporates behaving close and feeling close. Furthermore, the construct correlate strongly with multi-item measures such as the Relationship Closeness Inventory (Berscheid et al., 1989). To tap closeness between the partners, Aron et al. (1992, p. 597, Fig. 1) developed a one-item measure (“Please circle the picture below which best describes your relationship”) with seven sets of two increasingly overlapping circles, similar to Venn diagrams. One circle represents the self, and the other circle represents the partner, from barely overlapping circles (low degree of closeness) to the most overlapping circles (high degree of closeness).

Pietras et al. (2022a) studied the role IOS played for sexual satisfaction and sexual distress in a large representative sample of Germans aged 18–75. They found that IOS had a compensatory role for women with sexual problems, protecting them from experiencing sexual distress, and concluded that the IOS Scale is an interesting tool for both research and treatment. Pietras and Briken (2021) reviewed 24 studies on the relationship between the IOS scale and topics such as relationship preference, need-fulfilment, sexual satisfaction and functioning, couple’s sexuality and mental health, sexual desire and motivation, and prevention of sexually transmitted infections published between 2000 and 2019. They found positive associations between IOS and sexual well-being, functioning, desire, frequency and satisfaction, and a negative relation to sexual distress. Their findings are supported by the findings from other studies, which has shown that the IOS scale is understandable, psychologically meaningful, and reliable (Gächter et al., 2015). Furthermore, IOS in committed relationships was found to be an important predictor of relationship quality, well-being, and satisfaction (Frost & Forrester, 2013; Le et al., 2010; Tsapelas et al., 2009), as well as relationship duration (Branand et al., 2019).

The perception of closeness may well be highest at the beginning of a relationship and decrease over time in accordance with the challenges that many couples encounter and must cope with. The first stages of a romantic relationship are usually characterized by being (passionately) in love, bonding, and a feeling of closeness, and high hopes for a long-term committed relationship (Meuwly & Schoebi, 2017). It could be argued that this is because the couple has not had time to encounter major differences between them and the accompanying conflicts. No two individuals are exactly alike, and therefore, conflicts are eventually bound to appear and put the feeling of closeness to the test. Thus, it may be assumed that the perception of closeness grows as a function of being able to address and resolve conflicts (Ihlen & Ihlen, 2014). Every conflict has an element of rejection, and the perception of closeness therefore depends on the individual’s ability to endure the feeling of being rejected by the partner. Individuals’ ability to solve conflicts is likely to depend on their personal resources, life experiences, and how long the couple has spent together (Bradbury & Karney, 2004; Pietromonaco et al., 2004). A key factor in solving conflicts is the ability to communicate with the partner over conflicts that may arise (Byers, 2005). Some individuals may be well-equipped to handle conflicts as they arise; others may avoid conflicts and become silent and withdrawn instead of solving problems, often with the intention of preserving harmony in the couple relationship (Ihlen & Ihlen, 2014). Ironically, the consequence of the latter strategy may be the exact opposite of the intention, and result in a feeling of less closeness to the partner.

The Relationship Between IOS and Relationship Duration–Gendered Patterns?

Even though there may be individual differences in how conflicts are handled, it can be assumed that younger adults and adults who have been in the relationship for a shorter time are less well-equipped to solve relationship conflicts, mostly because they have not yet had the time to develop conflict-solving skills. Older adults have had the chance to be in a relationship for a longer period than younger adults, which means that older adults and more experienced individuals could be expected to be more equipped to solve conflicts (Bradbury & Karney, 2004). On the other hand, people who have been together for a long time may also experience relationship strain and feel that their lives together have become routine-like and less exciting. In turn, this experience could make them feel less close to their partners. Age and relationship duration do not always overlap, as people are serial monogamists and break up from relationships and enter into new relationships at all ages (Schmidt, 1989; Træen, 1993; Træen et al., 2018a, 2018b). In doing so, a new relationship may thus be related to feeling close to the partner regardless of age.

The association between IOS and relationship duration may differ between men and women. Aron et al. (1992) argued that the longer a man has known his spouse, the closer he will feel, which suggests that closeness in men builds over time, while closeness for women, is unrelated to or negatively related to relationship duration. Aron et al. (1992) suggest that one reason may be that women are more likely to stay in relationships that do not increase the perception of closeness over time. Alternatively, women may be more likely than men to idealize the partner in initial stages of a relationship, put more emphasis on emotions as grounds for feeling closeness, and over time the feeling of closeness may decline as idealization fades and ongoing conflicts may interfere with her intimate personal activities (Aron et al., 1992).

Closeness and Sexual Activity

According to Schmidt (1989), contemporary intimate relationships are much more dependent on emotions and sexuality than in previous generations. Research indicates that sexual activity is negatively affected in a long-term relationship by boredom, the degree of routine, and lack of variation (DeLamater & Moorman, 2007; Kontula & Haavio-Mannila, 2009; Stroope, et al., 2015). Also, sexuality within the dyad is shown to be associated with feeling close to, and intimate with, one’s partner (Avis et al., 2005; DeLamater, 2012; Galinsky & Waite, 2014; Stroope et al., 2015; Træen et al., 2013). In a longitudinal study, Byers (2005) found that the direction of the association between relationship and sexual satisfaction did not differ between men and women. Pietras and Briken (2021) studied the role of IOS in couples’ sexual satisfaction and sexual distress in a representative German sample. The researchers found that IOS was robustly and positively associated with sexual satisfaction and showed a compensatory role in protecting women and men with sexual problems from sexual distress. Another finding of this study was that IOS was not conceptually identical to love. Furthermore, Pietras et al. (2022a, 2022b) concluded that couples’ sexual satisfaction was related to non-sexual aspects of the relationship, indicating that relational aspects such as closeness and love should be included in research on couples’ sexual satisfaction.

Sexual activity is more than sexual intercourse, and masturbation activity must also be considered. A recent Norwegian study found that men with high sexual intercourse frequency were more likely to be sexually satisfied (Fischer & Træen, 2022). This allude to a compensatory masturbation pattern for men, where masturbation is regarded as unnecessary if one has highly satisfying sex-life and frequent sexual intercourse (Fischer & Træen, 2022). If closeness to the partner is associated with sexual satisfaction, this could imply that men with low masturbation activity may feel closer to their partner. Women with higher sexual intercourse frequency, and who were sexually experimenting, were more likely to report higher masturbation frequency in combination with higher sexual satisfaction (Fischer & Træen, 2022). This suggests a complementary masturbation pattern for women. Hence, this could imply that women with high masturbation activity may feel closer to their partner. According to Fischer and Træen (2022), this gendered masturbation pattern support gender-specific models–a notion supported by other studies (Carvalheira & Leal, 2013; Fischer et al., 2021; Gerressu et al., 2008; Regnerus et al., 2017), and an indication that the analysis of IOS should be conducted separate for men and women.

A recent Norwegian study showed that monogamous people scored relatively high on relationship satisfaction, whereas people with non-consensual non-monogamy reported lower relationship satisfaction (Træen & Thuen, 2021). Thus, the experience of non-monogamy may also be related to IOS, as a common motive for non-monogamy is dissatisfaction with the primary relationship and the sex-life (Hackathorn & Ashdown, 2020; Previti & Amato, 2004; Treas & Giesen, 2000; Træen & Thuen, 2021). The main reasons for non-monogamy are that sexual and emotional needs are not met within the primary relationship, and they seek to meet their needs with another person (Omarzu et al., 2012). This implies that less IOS may be related to non-monogamous experiences, particularly if the non-monogamy is non-consensual (Træen & Thuen, 2021).

Closeness and Body Image

According to the sociocultural perspective, Western society places high importance on physical appearance, with a thin body ideal for women and a lean and muscular body ideal for men (Tiggemann, 2011). In general, research has found an association between physical appearance dissatisfaction, fear of emotional intimacy, and a lack of trust in one’s partner (Lee & Thomas, 2012, as cited in Lee, 2016), factors that are known barriers to relationship satisfaction (Lyvers et al., 2022). In a relationship context, individual satisfaction with physical appearance is not necessarily influenced by what one´s partner actually thinks, but more whether the partner is perceived to be satisfied with one´s appearance (Hockey et al., 2021; Lee, 2016). For example, women tend to overrate the magnitude to which men find thinness in women attractive, while men overrate the extent to which women prefer male muscular body types (Demarest & Allen, 2000). According to Murray (2006), the assumption that the partner finds you less attractive may lead to defensively undermining your partner, thus negatively impacting both relationship and sexual satisfaction. However, other studies have shown that being in a close relationship may function as a buffer against the negative influence of societal thin-body ideals for women (e.g., Juarez & Pritchard, 2012)

Laus et al. (2018) reported an association between more body dissatisfaction with relationship duration in both men and women, while other studies (e.g., Goins et al., 2012) commonly find less body dissatisfaction in longer relationships. A possible explanation put forward by Laus et al. was that perhaps less positive feedback about appearance is received from partners over the years. For women, body satisfaction was predicted by feelings of closeness with a partner, while relationship commitment predicted body dissatisfaction (Laus et al., 2018), suggesting that closeness in a relationship may be associated with more acceptance regarding appearance than commitment.

After menopause, many women gain body weight, especially around the waist, and the distance from the thin hourglass-shaped body ideal increases (Swami, 2015). Being overweight is closely related to body dissatisfaction, which has been associated with lower sexual satisfaction in both younger and older adults (Kvalem et al., 2019; Kvalem et al., 2020). Sexual dissatisfaction is likely to affect older women’s feelings of closeness to their spouse. Clearly, satisfaction with body weight may also affect men’s feelings of closeness with their partners. However, we argue that penile satisfaction may be of greater importance in this respect. Penis appearance and function are related to men’s perception of masculinity, and Tiggemann et al. (2008) found, for example, that 68% of men wanted a larger penis, while 50% wanted lower body weight. Men suffer a loss of sexual function with increasing age, and nearly half of the men over the age of 60 experience erectile difficulties (Hald et al., 2019). Hurd Clarke and Korotchenko (2011) found that age-related changes in body function had a more negative impact on older men’s body evaluations than women. Men who are satisfied with the appearance of their penis may also be more likely to have a stronger perception of preserved masculinity and subsequently feel closer to their partners. Satisfaction with genital appearance has been less studied among women; however, Komarnicky et al. (2019) reported a positive association with sexual satisfaction in women.

Purpose

This study aims to describe the feeling of closeness with a permanent partner in relation to the duration of the relationship in a web panel sample of the Norwegian population in 2020. Based on the existing literature, we propose the following research questions:

-

RQ1:Is the relationship between IOS and relationship duration linear for both men and women and highest in the beginning of a long-term relationship? If there is a positive association between IOS and relationship duration, does this association differ for men and women?

-

RQ2: Is IOS increasingly correlated with relationship satisfaction, sexual satisfaction, and the level of sexual activity with increasing relationship duration?

-

RQ3: Is IOS associated with the experience of past non-monogamy, and does this connection vary with the duration of the relationship?

-

RQ4: Is IOS associated with the satisfaction with one’s physical appearance, and does this association vary with the duration of the relationship?

Methods

Participants and Recruitment

In March 2020, 11,685 members of Kantar’s web panel were randomly invited to participate in an online sexuality survey. Of those asked to participate, 4160 individuals aged between 18 and 89 years completed the questionnaire, yielding a response rate of 35.6%. Fifty-one percent of the individuals completed an online survey on their mobile phones. Kantar’s web panel contains approximately 40,000 active members (https://www.galluppanelet.no/). All members were randomly recruited through national phone registries; self-recruitment was not possible. Kantar’s web panel represents Norway’s population of Internet users, which, in turn, reflects 98% of the population with access to the Internet (see http://www.medienorge.uib.no/english/). The members of the Gallup Panel were regularly contacted to fill out online questionnaires. To motivate participation, Kantar operates with small incentives (e.g., lotteries and occasional surprises of varied quality). These incentives are not sufficiently large to attract study participation. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the participants were guaranteed anonymity.

All research complied with the Personal Data Act and the guidelines of the Norwegian Data Protection Authority followed the ethical guidelines developed for market and poll organization surveys (Norway’s Market Research Association and the European Society for Opinion and Marketing Research [ESOMAR]). The methods and sample characteristics have been presented in greater detail elsewhere (Fischer & Træen, 2022; Træen & Thuen, 2021; Træen et al., 2021a, 2021b).

Survey Questions

The questionnaire contained sociodemographic questions (self-identified gender, age, marital status, place of residence, and level of education). Additionally, the questionnaire contained questions adapted from the British National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (NATSAL-3) study (Mercer et al., 2013; Mitchell et al., 2013), the German GeSid survey (https://gesid.eu/studie/), and questions about sexual behavior used in previous Norwegian and Nordic studies (Kvalem et al., 2014; Lewin et al., 2000; Træen et al., 2016; Træen & Stigum, 2010; Træen et al., 2018a, 2018b). The average time to complete the survey was 15 minutes.

Sociodemographic Characteristics of the Sample

Kantar registered several social background characteristics of its web panel members, including assigned gender at birth. Based on Kantar’s registration, 47.6% of the participants were women and 52.4% were men. The mean age of men was 48.4 years (SD 17.1 years), while the mean age of the women was 44.4 years (SD 16.8 years). Most participants (63.4%) reported living with a partner, 25.4% reported being unmarried, 8.4% were separated or divorced, and 2.8% were widowed. Regarding place of residence, most participants lived in urban areas (56.8%) and only 16.3% lived in rural areas. The majority of men and women reported higher education, with 41.4% reporting a short university education (Bachelor’s degree) and 22.8% reporting a long university education (Master’s degree or higher). Most participants reported that they had no religious affiliation (59.5%) while 38.7% were Christians, mainly Protestants or Christians with no particular denomination. The proportion of participants who identified as heterosexual was 93.5%, while 2.6% identified as homosexual/lesbian, 3.3% as bisexual/pansexual, and 0.6% as asexual. This study focused on 2,639 participants who were married, cohabiting, or in registered partnerships (1432 men and 1207 women).

Measures

Closeness to partner (IOS)—This measure was adapted from Aron et al. (1992), and is described in greater detail in their paper. The measure was also used in the German Sex Survey, 2019 (www.gesid.eu). The instruction to the participants was: “These figures attempt to portray how close two persons may feel to each other. Choose the figure that best describes your relationship with your partner (see the illustration below).” Closeness was rated on a 7-point scale from low degree of closeness (A = 1) to high degree of closeness (G = 7).

Satisfaction with appearance This was measured by two questions adapted from studies on body image (Frederick et al., 2016; Sandhu & Frederick, 2015; Swami, 2020): “How dissatisfied or satisfied are you with your weight?” and “How dissatisfied or satisfied are you with your genital appearance?”. The response categories were measured on a 7-point scale from very dissatisfied (1), through neither nor (4), to very satisfied (7). Higher scores indicated higher satisfaction with weight and genital appearance.

Frequency of sexual intercourse and frequency of masturbation It was measured with the two questions “How many times have you had sexual intercourse (vaginal, anal, or oral sex) during the last month?” and “How many times have you /masturbated during the last month?” The response categories were no times (1), once a month (2), two or three times a month (3), once a week (4), two or three times per week (5), once a day (6), and more often than once a day (7). The questions were modified versions of those previously used in the Healthy Sexual Ageing Project (Træen et al., 2018a, b).

Sexual satisfaction This was measured by the question “All things considered, how satisfied are you with your sexual life?” Satisfaction with the level of sexual activity – was tapped by the question “In general, how satisfied are you with your current level of sexual activity?” For both questions, the responses were provided on a 5-point scale: very dissatisfied (1), somewhat dissatisfied (2), neither satisfied nor dissatisfied (3), quite satisfied (4), and very satisfied (5). The questions were modified versions of those previously used in the Healthy Sexual Ageing Project (Træen et al., 2018a, 2018b).

Experience of non-monogamy was measured by the question “Have you ever, while married or cohabiting, had sex with someone other than your primary partner?” The response categories were: no (1), yes, without my partner’s consent (2), and yes, with my partner’s consent (3). The question was previously used in a survey of 18–29-year-olds in Norway in 2013 (Kvalem et al., 2014), in the German Sex Survey 2019 (www.gesid.eu), and in the present sample (see Træen & Thuen, 2021).

Gender was coded as male (0) and female (1).

Age was measured as a continuous variable in number of years.

Marital status was tapped by the question: “What is your marital status?” with the response categories unmarried (1), separated/divorced (2), widow/widower (3), and married/cohabitant/registered partnership (4). In the present study, only those who ticked category 4 were included.

Relationship duration This was calculated as the difference between 2020 (year of the study) and the response to the question “In which year were you married/cohabiting/registered partner with your current spouse/partner?” The continuous variable was recoded into 0−6 years (1) (n = 721), 7−20 years (2) (n = 826), 21−30 years (3) (n = 326), and 31 years or more (4) (n = 671).

Statistical Analyses

All data analyses were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 26.0. Initially, we analyzed IOS by relationship duration using the continuous variables in the total sample and no conclusive pattern was found. For this reason, we conducted separate analyses for men and women, and found that the relationship appeared linear for women, but not for men. For men, the curve turned after a relationship duration of 30 years or more. On this background, we decided to recode the relationship duration variable into a categorical variable. In addition, we took into account to have a sufficient large n in each group. Variance analysis (ANOVA) was used to test mean group differences, and partial eta squared was calculated to indicate the effect size: 0.01 (small), 0.06 (medium), and 0.14 (large).

Bivariate correlation (Pearson’s correlation coefficient) was calculated to measure the strength of the association between IOS and the selected sexuality and relationship variables. According to Gignac and Szodorai (2016), the effect sizes of small, medium, and large corresponded to correlations of 0.10, 0.20, and 0.30, respectively.

Results

Table 1 shows IOS by relationship duration for all participants and separately for men and women. IOS was highest for participants who had been with their partner for a shorter period (0−6 years), and lowest among those who had been with their partner for 21−30 years.

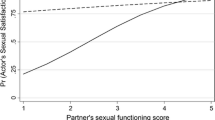

In men, IOS was highest for participants who had been with their partner for shorter (0−6 years) and longer (31 years or more) periods of time, and lowest among men who had been with their partner for 7−20 years or 21−30 years. In women, IOS was highest for participants who had been with their partner for a short time (0−6 years) and lowest among women who had been with their partner 31 years or more. These differences between genders, particularly among those with a relationship duration of 31 years or more, are illustrated in detail in Figure 2.

Table 2 shows an overview of the differences in age, level of satisfaction with aspects of sexuality and appearance, and frequency of sexual activity between the relationship duration groups. A main effect of relationship duration for men was found for age, satisfaction with weight, appearance of genitals, sexual activity, and sexual life in general, as well as intercourse and masturbation frequency the last month. The same significant main effects emerged for women with the exception of satisfaction with weight and appearance of the genitals. Longer relationship duration was associated with more lifetime experience with non-consensual non-monogamy for both men and women.

Table 3 shows the bivariate correlations between IOS and the selected sexual variables in men and women with different relationship durations.

The results showed that IOS correlated strongly with sexual satisfaction for men and moderately to strongly for women for all durations of the relationship. Furthermore, IOS correlated moderately to strongly with satisfaction with the level of sexual activity among men and women for all durations of the relationship, except for small correlations for women who had been with their partner for 7−20 years and 31 years or more. Moving from the perception of satisfaction to actual behavior, IOS correlated moderately to strongly with the frequency of sexual intercourse in men for all durations of the relationship. In women who had lived with their partner for 0−6 years or 21−30 years, IOS correlated strongly with frequency of sexual intercourse, while there was a small correlation with IOS in the group with a relationship duration of 7−20 years. Last, IOS correlated significantly with a lower frequency of masturbation in all men except those who had been with their partner for 7−21 years. In women, IOS did not correlate significantly with the frequency of masturbation.

Sexual satisfaction, and satisfaction with the level of sexual activity seem equally important for IOS in men who have been with their partner for both short and long periods. Sexual intercourse frequency was strongly correlated with IOS in men for all relationship durations. In women who had been with their partners for 31 years or more, this correlation was not statistically significant.

Initially, multiple linear regression analyses of the relationships between IOS and age, level of education, place of residence, and sexual orientation were conducted across different relationship durations. These analyses showed a significant relationship only between IOS and age. Therefore, age was included in the analyses of the relationship between age, satisfaction with genital appearance and weight, sexual satisfaction, sexual activity, lifetime experience of non-monogamy, and IOS in men and women across different relationship durations (Table 4). In men, the explained variance of the model ranged from 13.3% among those with a relationship duration of 0−6 years, to 25.2% with a relationship duration of 21−30 years. In women, the explained variance of the model was highest among those with a relationship duration of 21−30 years (R2 = 21.2%).

Irrespective of relationship duration, the most important factor for both men and women’s perceived closeness with their partner was general sexual satisfaction. Among men who had lived with their partner for 7−20 years or 31 years or more, having been monogamous in life was significantly associated with IOS. Furthermore, IOS was associated with higher intercourse frequency, lower masturbation frequency, and satisfaction with genital appearance in men who had been with their partner for 31 years or longer. Intercourse frequency was significantly associated with IOS in women who had been with their partner for 0−6 years. Furthermore, in women who had been with their partner for 31 years or more, satisfaction with their own weight was important for IOS.

Discussion

In summary, IOS was highest for men and women who had been with their partner for 0−6 years. However, among those who had been with their partner for 31 years or more, men felt closer to their partners than women. Irrespective of relationship duration, the most important factor for both men and women’s perceived closeness with their partner was general sexual satisfaction. Among men who had lived with their partner for 7−20 years or 31 years or longer, having been monogamous in life was significantly associated with IOS. Furthermore, IOS was associated with higher intercourse frequency, lower masturbation frequency, and satisfaction with genital appearance in men who had been with their partner for 31 years or more. Intercourse frequency was significantly associated with IOS in women who had been with their partner for 0−6 years, but was not associated with masturbation frequency. These findings partly correspond to the findings from other studies (Fischer & Træen, 2022). Furthermore, in women who had been with their partner for 31 years or more, satisfaction with their own weight was important for IOS. It could be that women feel less closeness with their partners because this is the time when children move away from the parent home about this time, and that may be a huge change for women as caregivers. Caring for children and parenting could make women feel closer to their partners (Nagy & Theiss, 2013).

Participants in this study expressed a relatively high degree of closeness with their partners. However, compared to partnered Germans, partnered Norwegians were shown to have an increased likelihood of reporting less IOS in their relationships (Pietras et al., 2022a, 2022b). This result may express a true cross-cultural difference in IOS between the two countries, but it may also be the result of methodological and sample differences. However, nationality had no significant effect on the correlation between IOS and sexual intercourse frequency in the past four weeks, which suggests that the association is more universal than country-specific.

As expected, we found that IOS was highest among those with a relationship duration of 0–6 years and declined thereafter to reach the lowest point among those with a relationship duration of 21−30 years. Accordingly, it seems that the association between IOS and relationship duration was not linear. Second, we found that men who had spent a long time with their partner felt closer to their partner than men who had spent a shorter time with their partner and that IOS in women was negatively related to relationship duration. Among individuals who had been with their partner for 31 years or longer, IOS took the opposite path for men and women. The decline in IOS continued in women but increased in men. Finally, we found that IOS, irrespective of relationship duration, was related to sexual satisfaction, and sexual activity. In this context, it is of interest that Byers (2005), who examined the association between relationship and sexual satisfaction two times 18 months apart in 87 individuals in long-term relationships, found that relationship and sexual satisfaction changed concurrently; and that the quality of intimate communication accounted for part of the concurrent changes in relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction.

As expected, and in accordance with previous research findings, longer relationship duration was associated with both lower sexual activity and sexual satisfaction for both men and women (e.g. Træen et al., 2018a, 2018b). However, men in relationships of longer duration were more dissatisfied with their weight, and the appearance of their genitals in particular, while no relationship duration group differences in appearance satisfaction were found among women. This supports the findings of Hurd Clarke and Korotchenko (2011) that age-related changes may have a more negative impact on older men's body evaluations than women.

The relationships between IOS and sexual satisfaction and activity were generally stronger for men than for women, and stronger for sexual satisfaction than for sexual frequency variables. This supports previous research that found a strong association between perception of intimacy and relationship satisfaction (McCabe, 1997, 1999; Moore et al., 2001). Staying monogamous throughout the relationship is increasingly important for men but not for women; this could indicate that not having an extradyadic affair for men serves as a way of focusing on the spouse over time, and by excluding the thought that “the grass is greener on the other side” they may also feel closer to the partner.

Why do men who have been with their partners for 31 years or more feel closer to them, whereas women in the same situation express feeling less close? Establishing and maintaining intimate relationships is a primary motivation throughout life, and cognitive and relational schemata on how to make and maintain attachments are critical for understanding psychological well-being (Jack, 1991, 1999; Jack & Ali, 2010). Dana Jack advocated that women have traditionally been socialized to put others’ needs first and silence certain feelings, thoughts, and actions to maintain harmony within their committed relationships. In this context, Træen et al. (2021a, 2021b) found that partnered Norwegian and Croatian men aged 65 years and older (mean age of male participants was 74.3 years and mean relationship duration 41.2 years; mean age of female participants was 71.2 years and mean relationship duration 40.6 years) were silencing their self in sexual situations more than women. We may be dealing with a more modern or liberal generation of men who learned to put women’s sexual needs first and thus became more prone to self-silencing. However, this finding may also reflect the dynamics of a long-term relationship, and a change from the fact that women are more self-silenced than men at the beginning of a relationship to the opposite. The longer the couple sticks together, and by mutual adjustment and accommodation, partners’ self-silencing gradually converges. For females, this adjustment may occur through learning that self-silencing is not an efficient strategy for improving sexual and emotional well-being. However, this insight may also come with a price in the sense that the change comes too late in the relationship–at a time when the woman, in reality, has resigned and given up on her partner. She no longer feels close to him.

For men, long-term relationship dynamics may promote communication about their emotional needs, especially if they feel that this leads to greater sexual satisfaction and harmony in the relationship. Psychological androgyny, a way of ruling out continued expressions of gender-appropriate behavior, may be important later in life (McCabe, 2009). McCabe (2009) claims that there is a rounding out of a man’s personality by a “feminine” dimension and vice versa for women. In addition, there is caring between men and women, and increasingly less segregation between genders, perhaps because they spend more time together after retirement. The “androgyny of later life” may encourage the articulation of long-standing emotions in relationships. This should make it easier for women to express assertiveness in sexual situations and for a man to express more respect and responsiveness to the female partner’s desires. This partly corresponds to Duarte and Thompson’s (1999) suggestion that men and women may have different perceptions of silencing their needs, even in sexual contexts. To men, silencing one’s needs may be an act of putting their partners’ needs first or an expression of suppressing emotions and affection; and to women, the same may represent giving in to social pressures and a “loss of self.” Aging men experience reduced levels of testosterone, and after the age of 60 years, about one in two men has erectile difficulties (Hald et al., 2019). Not being able to perform sexually may lead to a perceived loss of masculinity (Clark, 2019; McDonagh et al., 2018) and feelings of “loss of self” (Jack, 1991). In younger years, the ability to perform sexually peaked; it could have been the man who desired sex more frequently and was the one not to silence his sexual needs. However, reduced sexual ability may lower his self-esteem and made him more self-effacing. In this context, men who were satisfied with the appearance of their genitals felt closer to their partner, indicating pride in manhood and masculinity. However, contrary to women, “loss of self” may not necessarily lead to the experience of a divided self (Jack, 1991, 1999; Jack & Ali, 2010). When men silence their sexual needs, this may increase the sense of harmony in the close relationship, making the partners equally important and bringing a connection where closeness is sought. This gives the female partner room to express herself sexually, and perhaps she dares to express herself more freely, perhaps because she is no longer afraid of being abandoned by her partner at this stage of life.

Qualitative findings indicate that older people find it difficult to view their aging body as sexually attractive and that for women, the aging body is associated with feeling a loss of sexual desirability (Montemurro & Gillen, 2012; Thorpe et al., 2015). Weight increase and the loss of the feminine hourglass thin body shape may lead to body shame and self-consciousness about appearance, and distract from the feeling of intimacy and sexual pleasure in the relationship (Carvalheira et al., 2017; Meana & Nunnink, 2006)

Strengths and Limitations

A clear strength of this study is the large sample size. However, this study has certain limitations that must be addressed. The response rate of previous Norwegian sexual behavior surveys dropped from 63% in 1987 to 23% in 2008 (Træen & Stigum, 2010). Even though the response rate in this survey was higher than that in 2008, the high dropout rate represents a possible source of bias. Other surveys have concluded that dropout from the survey was unrelated to sexual behavior and was random rather than systematic (Stigum, 1997). There is reason to believe that this also holds true for the present study and that the dropout is random rather than systematic.

It can reasonably be assumed, that couples who do not get along often break up during the first decade of a relationship. Their answers are accordingly missing from the groups with long relationship duration. It is possible that the subgroups with a relationship duration of 31 years or longer may differ in several aspects from those with a shorter relationship duration. They have avoided divorcing, as opposed to many others who have divorced and become single or started new relationship(s) in their course of life. They may have special qualities to endure long-term relationships that were not measured in this study to make them able to stick together with one person for a lifetime. Furthermore, to study how closeness and its correlates may change over time, longitudinal data are warranted. Our data are cross-sectional in nature; therefore, we are precluded from drawing conclusions about causality. Future research should examine these associations using other research designs and methods. In addition, this research examines IOS as a function of various satisfaction variables, but it may be the other way around and that IOS predicts the satisfaction variables. It is also likely that the associations are bidirectional, which is a task for future research.

In this study, we used single-item measures of satisfaction, which are unidimensional and may have low test-retest reliability (Mark et al., 2014). Single items were chosen to maximize response rates and reduce the time spent filling out the questionnaire. It is generally accepted to do this, and it is also frequently used in studies such as this (Gardner et al., 1998), It is believed that one obtains an acceptable measure of satisfaction. However, in future studies, validated satisfaction scales should ideally be included. Lastly, in future research, more effort should be made to determine how factors such as raising children and economic status may contribute to couples’ sense of IOS.

Implications

The results from this study have some implications for both future research and clinical work. Regarding future research, our study demonstrates the importance of not treating relationship duration as a continuous variable in statistical analyses, at least not for men. To be able to state more about the development of closeness to the partner, longitudinal studies should be implemented. Regarding clinical work, therapists should encourage couples to stay curious about their partner, and not take the partner for granted. This seems particularly important for couples who have survived the first six years together, and for women who have lived with their partner for more than 30 years. In this context, the therapist should help their clients to communicate with each other in a way which makes them rediscover their partner.

Conclusions

Men and women reported similar degrees and patterns of IOS up to the point where they have been in their relationship for more than 30 years. For both, IOS decreases the longer the couple have been together. There may be several explanations for this decrease, such as a less exciting sex-life and more routines taking over everyday life, which in turn gradually makes the partners less curious of each other. However, when a couple has stayed together for more than 30 years, a turning point occurs. It seems that women continue to feel less close to their partners, whereas for men, the perception of closeness increases. This turning point may be related to physiological, psychological, and social changes in men and women as they age.

Change history

02 February 2023

Missing Open Access funding information has been added in the Funding Note

References

Aron, A., Aron, E. N., & Smollan, D. (1992). Inclusion of other in the self-scale and the structure of interpersonal closeness. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(4), 596–612. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.4.596

Aron, A., Mashek, D. J., & Aron, E. N. (2004). Closeness as including other in the self. In D. J. Mashek & A. Aron (Eds.), Handbook of closeness and intimacy (pp. 37–52). Psychology Press.

Avis, N. E., Zhao, X., Johannes, C. B., Ory, M., Brockwell, S., & Greendale, G. A. (2005). Correlates of sexual function among multi-ethnic middle-aged women: Results from the study of women’s health across the nation (swan). Menopause: The Journal of The North American Menopause Society, 12(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.GME.0000151656.92317.A9

Berscheid, E., Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (1989). The Relationship Closeness Inventory: Assessing the closeness of interpersonal relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(5), 792. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.5.792

Bradbury, T. N., & Karney, B. R. (2004). Understanding and altering the longitudinal course of marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 66, 862–879. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.0022-2445.2004.00059.x

Branand, B., Mashek, D., & Aron, A. (2019). Pair-bonding as inclusion of other in the self: A literature review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2399. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02399

Byers, E. S. (2005). Relationship satisfaction and sexual satisfaction: A longitudinal study of individuals in long-term relationships. The Journal of Sex Research, 42(2), 113–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552264

Carvalheira, A., Godinho, L., & Costa, P. (2017). The impact of body dissatisfaction on distressing sexual difficulties among men and women: The mediator role of cognitive distraction. Journal of Sex Research, 54, 331–340. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2016.1168771

Carvalheira, A., & Leal, I. (2013). Masturbation among women: Associated factors and sexual response in a Portuguese community sample. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 39(4), 347–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2011.628440

Clark, J. N. (2019). The vulnerability of the penis: Sexual violence against men in the conflict and security frames. Men and Masculinities, 22(5), 778–800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1097184X17724487

DeLamater, J. (2012). Sexual expression in later life: A review and synthesis. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(2–3), 125–141. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2011.603168

DeLamater, J., & Moorman, S. M. (2007). Sexual behavior in later life. Journal of Aging and Health, 19(6), 921–945. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264307308342

Demarest, J., & Allen, R. (2000). Body image: Gender, ethnic, and age differences. The Journal of Social Psychology, 140, 465–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224540009600485

Duarte, L. M., & Thompson, J. M. (1999). Sex differences in self-silencing. Psychological Reports, 85, 145–161. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1999.85.1.145

Fischer, N., Graham, C. A., Træen, B., & Hald, G. M. (2022). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 1385–1396. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-021-02071-z

Fischer, N., & Træen, B. (2021). Prevalence of sexual difficulties and related distress, and the association with sexual avoidance in Norway. International Journal of Sexual Health, 34(1), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2021.1926040

Fischer, N., & Træen, B. (2022). A seemingly paradoxical relationship between masturbation frequency and sexual satisfaction. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 51, 3151–3167. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-022-02305-8

Frederick, D. A., Sandhu, G., Morse, P. J., & Swami, V. (2016). Correlates of appearance and weight satisfaction in a U.S. national sample: Personality, attachment style, television viewing, self-esteem, and life satisfaction. Body Image, 17, 191–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.04.001

Frost, D. M., & Forrester, C. (2013). Closeness discrepancies in romantic relationships: Implications for relational well-being, stability, and mental health. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39(4), 456–469. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167213476896

Gächter, S., Starmer, C., & Tufano, F. (2015). Measuring the closeness of relationships: A comprehensive evaluation of the “Inclusion of the Other in the Self” scale. PloS One. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129478

Galinsky, A. M., & Waite, L. J. (2014). Sexual activity and psychological health as mediators of the relationship between physical health and marital Quality. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 69, 482–492. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbt165

Gardner, D. G., Cummings, L. L., Dunham, R. B., & Pierce, J. L. (1998). Single-item versus multiple-item measurement scales: An empirical comparison. Educational and Psychological Measurements, 58(6), 898–915. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164498058006003

Gerressu, M., Mercer, C. H., Graham, C. A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2008). Prevalence of masturbation and associated factors in a British national probability survey. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 37(2), 266–278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-006-9123-6

Gignac, G., & Szodorai, E. (2016). Effect size guidelines for individual differences researchers. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 74–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.069

Goins, L. B., Markey, C. N., & Gillen, M. M. (2012). Understanding men’s body image in the context of their romantic relationships. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6(3), 240–248. https://doi.org/10.1177/1557988311431007

Hackathorn, J., & Ashdown, B. K. (2020). The webs we weave: Predicting infidelity motivations and extradyadic relationship satisfaction. The Journal of Sex Research. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2020.1746954

Hald, G. M., Graham, C., Štulhofer, A., Carvalheira, A. A., Janssen, E., & Træen, B. (2019). Prevalence of sexual problems and associated distress in aging men across four European Countries. Journal of Sexual Medicine, 16(8), 1212–1225. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.04.017

Hockey, A., Donovan, C. L., Overall, C. N., & Barlow, K. F. (2021). Body image projection bias in heterosexual romantic relationships: A dyadic investigation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 48(7). https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211025202

Hurd Clarke, L., & Korotchenko, A. (2011). Aging and the body: A review. Canadian Journal on Aging, 30, 495–510. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980811000274

Ihlen, B. M., & Ihlen, H. (2014). Ubehag. Hvordan vanskelige følelser kan gi gode relasjoner [Discomfort. How difficult feelings can lead to good relationships]. Cappelen Damm.

Jack, D. C. (1991). Silencing the Self: women and depression. Harvard University Press.

Jack, D. C. (1999). Silencing the Self: inner dialogues and outer realities. In T. Joiner & J. C. Coyne (Eds.), The interactional nature of depression: Advances in interpersonal approaches. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10311-008

Jack, D. C., & Ali, A. (2010). Silencing the Self across cultures: depression and gender in the social world. Oxford University Press.

Juarez, L., & Pritchard, M. (2012). Body dissatisfaction: Commitment, support, and trust in romantic relationships. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 22(2), 188–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2012.647478

Komarnicky, T., Skakoon-Sparling, S., Milhausen, R. R., & Breuer, R. (2019). Genital self-image: Associations with other domains of body image and sexual response. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 45(6), 524–537. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2019.1586018

Kontula, O., & Haavio-Mannila, E. (2009). The impact of aging on human sexual activity and sexual desire. The Journal of Sex Research, 46(1), 46–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490802624414

Kvalem, I. L., Graham, C., Hald, G. M., Carvalheira, A., Janssen, E., & Stulhofer, A. (2020). Body image and sexual satisfaction in partnered older adults: A population-based study in four European countries. European Journal of Ageing, 17, 163–173. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-019-00542-w

Kvalem, I. L., Træen, B., Lewin, B., & Štulhofer, A. (2014). Self-perceived effects of Internet pornography use, genital appearance satisfaction, and sexual self-esteem among young Scandinavian adults. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2014-4-4

Kvalem, I. L., Træen, B., Markovic, A., & von Soest, T. (2019). Body image development and sexual satisfaction: A prospective study from adolescence to adulthood. Journal of Sex Research, 56(6), 791–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2018.1518400

Laus, M. F., Almeida, S. S., & Klos, L. A. (2018) Body image and the role of romantic relationships. Cogent Psychology, 5(1). https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2018.1496986

Le, B., Dove, N. L., Agnew, C. R., Korn, M. S., & Mutso, A. A. (2010). Predicting nonmarital romantic relationship dissolution: A meta-analytic synthesis. Personal Relationships, 17(3), 377–390. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6811.2010.01285.x

Lee, C. E. (2016). Body image and relationship satisfaction among couples: The role of perceived partner appearance evaluations and sexual satisfaction. [Doctoral dissertation, University of Windsor]. https://scholar.uwindsor.ca/etd/5836.

Lewin, B. (Ed.), Fugl-Meyer, K., Helmius, G., Lalos, A., & Månsson, S. A. (2000). Sex in Sweden. On the sex-life in Sweden 1996. Uppsala Universitetsförlag.

Lyvers, M., Pickett, L., Needham, K., & Thorberg, F. A. (2022). Alexithymia, fear of intimacy, and relationship satisfaction. Journal of Family Issues, 43(4), 1068–1089. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X211010206

Mark, K. P., Herbenick, D., Fortenberry, J. D., Sanders, S., & Reece, M. (2014). A psychometric comparison of three scales and a single-item measure to assess sexual satisfaction. Journal of Sex Research, 51(2), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2013.816261

McCabe, J. (2009). Psychological androgyny in later life: A psychocultural examination. Ethos, 17(1), 3–31. https://doi.org/10.1525/eth.1989.17.1.02a00010

McCabe, M. P. (1997). Intimacy and quality of life among sexually dysfunctional men and women. Journal of Sex and Marital Therapy, 23, 276–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/00926239708403932

McCabe, M. P. (1999). The interrelationships between intimacy, relationship functioning, and sexuality among men and women in committed relationships. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 8(1), 31–38.

McDonagh, L. K., Nielsen, E. J., McDermott, D. T., Davies, N., & Morrison, T. G. (2018). I want to feel like a full man: Conceptualizing gay, bisexual and heterosexual men’s sexual difficulties. Journal of Sex Research, 55(6), 783–801. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1410519

Meana, M., & Nunnink, S. E. (2006). Gender differences in the content of cognitive distraction during sex. Journal of Sex Research, 43, 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490609552299

Meuwly, N., & Schoebi, D. (2017). Social psychological and related theories on long-term committed romantic relationships. Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences, 11(2), 106–120. https://doi.org/10.1037/ebs0000088

Mercer, C. H., Tanton, C., Prah, P., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Lewis, R., Field, N., Datta, J., Copas, A. J., Phelps, A., Wellings, K., & Johnson, A. M. (2013). Changes in sexual attitudes and lifestyles in Britain through the life course and over time: Findings from the National Surveys of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal). Lancet, 382(9907), 1781–1794. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62035-8

Mitchell, K. R., Mercer, C. H., Ploubidis, G. B., Jones, K. G., Datta, L., Field, N., Copas, A. J., Tanton, C., Erens, B., Sonnenberg, P., Clifton, S., Macdowall, W., Phelps, A., Johnson, A. M., & Wellings, K. (2013). Sexual function in Britain: findings from the third National Survey of Sexual Attitudes and Lifestyles (Natsal-3). The Lancet, 382, 1817–1829. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)62366-1

Moore, K. A., McCabe, M. P., & Brink, R. B. (2001). Are married couples happier in their relationships than cohabiting couples? Intimacy and relationship factors. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 16(1), 35–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990125384

Montemurro, B., & Gillen, M. M. (2012) Wrinkles and sagging flesh: Exploring transformations in women's sexual body image. Journal of Women & Aging, 25, 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08952841.2012.720179

Murray, S. L., Holmes, J. G., & Collins, N. L. (2006). Optimizing assurance: The risk regulation system in relationships. Psychological Bulletin, 132, 641–666. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.132.5.641

Nagy, M. E., & Theiss, J. A. (2013). Applying the relational turbulence model to the empty-nest transition: Sources of relationship change, relational uncertainty, and interference from partners. Journal of Family Communication, 13(4), 280–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/15267431.2013.823430

Omarzu, J., Miller, A. N., Schultz, C., & Timmerman, A. (2012). Motivations and emotional consequences related to engaging in extramarital relationships. International Journal of Sexual Health, 24(2), 154–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2012.662207

Pietras, L., Fedorowicz, C., Matthiesen, S., & Træen, B. (2022b). Effect of inclusion of other in the self on sexual behavior in Germany and Norway (Manuscript in preparation).

Pietras, L., & Briken, P. (2021). Inclusion of other in the self and couple’s sexuality: A scoping review. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 47(3), 285–304. https://doi.org/10.1080/0092623X.2020.1865494

Pietras, L., Wiessner, C., & Briken, P. (2022a). How Inclusion of Other in the Self relates to couple’s sexuality and functioning—Results from the German Health and Sexuality Survey (GeSiD). The Journal of Sex Research, 59(4), 493–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1998307

Pietromonaco, P. R., Greenwood, D., & Barrett, L. F. (2004). Conflict in adult close relationships: An attachment perspective. In W. S. Rholes & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), Adult attachment: New directions and emerging issues. Guilford Press.

Previti, D., & Amato, P. R. (2004). Is infidelity a cause or a consequence of poor marital quality? Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 21, 217–230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407504041384

Regnerus, M., Price, J., & Gordon, D. (2017). Masturbation and partnered sex: Substitutes or complements? Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(7), 2111–2121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-017-0975-8

Sandhu, G., & Frederick, D. A. (2015). Validity of one-item measures of body image predictors and body satisfaction. Poster Presented at the Meeting of the Western Psychology Association.

Schmidt, G. (1989). Sexual permissiveness in Western societies. Roots and course of development. Nordisk Sexologi, 7, 225–234.

Stigum, H. (1997). Mathematical models for the spread of sexually transmitted diseases using sexual behavior data. Norwegian Journal of Epidemiology, 7(suppl no. 5).

Stroope, S., McFarland, M. J., & Uecker, J. E. (2015). Marital characteristics and the sexual relationships of U.S. older adults: An analysis of national social life, health, and aging project data. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 44(1), 233–247. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-014-0379-y

Swami, V. (2015). Cultural influences on body size ideals: Unpacking the impact of Westernization and modernization. European Psychologist, 20(1), 44–51. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000150

Swami, V., Tran, U. C, Barron, D., Afhami, R., Aime, A., Almenara, C. A., Alp Dal, N., Amaral, A. C. S., Anjum, S. A. G., Argyrides, M., Atari, M., Aziz, M., Banai, B., Borowiec, J., Brewis, A., Cakir Kocak, Y., Campos, J. A. D. B., Carmona, C., Chaleeraktrakoon, T.,... Voracek, M. (2020). The breast size satisfaction survey (BSSS): Breast size dissatisfaction and its antecendents and outcomes in women from 40 nations. Body Image, 32, 199–217. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.001.006

Thorpe, R., Fileborn, B., Hawkes, G., Pitts, M., & Minichiello, V. (2015). Old and desirable: Older women's accounts of ageing bodies in intimate relationships. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 30, 156–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2014.959307

Tiggemann, M. (2011). Sociocultural perspectives on human appearance and body image. In T. F. Cash & L. Smolak (Eds.), Body image. A handbook of science, practice, and prevention (pp. 12–19). The Guilford Press.

Tiggemann, M., Martins, Y., & Churchett, L. (2008). Beyond muscles: Unexplored parts of men’s body image. Journal of Health Psychology, 13, 1163–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308095971

Træen, B. (1993). Norwegian adolescents' sexuality in the era of AIDS. Empirical studies on heterosexual behaviour. Thesis. Faculty of Medicine, University of Oslo.

Træen, B., Fischer, N., & Kvalem, I. L. (2021). Sexual variety in Norwegian men and women of different sexual orientations and ages. Journal of Sex Research, 59(2), 238–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2021.1952156

Træen, B., Hansen, T., & Stulhofer, A. (2021). Silencing the sexual self and relational and individual well-being in later life: A gendered analysis of north versus south of Europe. Sexual and Relationship Therapy. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.1883579

Træen, B., Markovic, A., & Kvalem, I.L. (2016). Sexual satisfaction and body image: A cross-sectional study among Norwegian young adults. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 31(2), 123–137. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2015.1131815

Træen, B., & Stigum, H. (2010). Sexual problems in 18–67-year-old Norwegians. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 38(5), 445–456. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810371245

Træen, B., Stulhofer, A., & Carvalheira, A. (2013). Satisfaction with the division of housework, partner’s perceived attractiveness, emotional intimacy, and sexual satisfaction in married or cohabiting Norwegian middle-class men. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 28(3), 215–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2013.808323

Træen, B., Stulhofer, A., Janssen, E., Carvalheira, A. A., Hald, G. M., Lange, T., & Graham, C. (2018). Sexual activity and sexual satisfaction among older adults in four European countries. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 48(3), 815–829. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1256-x

Træen, B., Štulhofer, A., Jurin, T., & Hald, G. M. (2018). Seventy-five years old and still going strong: Stability and change in sexual interest and sexual enjoyment in men and women across Europe. International Journal of Sexual Health, 30(4), 323–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2018.1472704

Træen, B., & Thuen, F. (2021). Non-consensual and consensual non-monogamy in Norway. International Journal of Sexual Health. https://doi.org/10.1080/19317611.2021.1947931

Treas, J., & Giesen, D. (2000). Sexual infidelity among married and cohabiting Americans. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 62, 48–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2000.00048.x

Tsapelas, I., Aron, A., & Orbuch, T. (2009). Marital boredom now predicts less satisfaction 9 years later. Psychological Science, 20(5), 543–545. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2009.02332.x

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Oslo (incl Oslo University Hospital).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors have no relevant financial or non-financial interests to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Træen, B., Kvalem, I.L. The Longer it is, the Closer One Feels: Perception of Emotional Closeness to the Partner, Relationship Duration, Sexual Activity, and Satisfaction in Married and Cohabiting Persons in Norway. Sexuality & Culture 27, 761–785 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10037-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-022-10037-z