Abstract

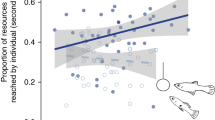

Researchers commonly use long-term average production inequalities to characterize cross-cultural patterns in foraging divisions of labor, but little is known about how the strategies of individuals shape such inequalities. Here, we explore the factors that lead to daily variation in how much men produce relative to women among Martu, contemporary foragers of the Western Desert of Australia. We analyze variation in foraging decisions on temporary foraging camps and find that the percentage of total camp production provided by each gender varies primarily as a function of men’s average bout successes with large, mobile prey. When men target large prey, either their success leads to a large proportional contribution to the daily harvest, or their failure results in no contribution. When both men and women target small reliable prey, production inequalities by gender are minimized. These results suggest that production inequalities among Martu emerge from stochastic variation in men’s foraging success on large prey measured against the backdrop of women’s consistent production of small, low-variance resources.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

These data refer to the time McCarthy and McArthur (1960) spent at Fish Creek. Their detailed narrative covers observations on subsistence activities for fourteen days from October seventh to October twentieth. Men’s and women’s relative contributions were calculated by extracting the time each forager spent searching, pursuing, and transporting resources and the weight of resources acquired. When two or more individuals participated, the total was divided by the number of foragers. Weight was converted to kilocalories following Brand-Miller et al. (1993). Complete information was available for a total of 30 bouts (12 women-only, 14 men-only, and 4 mixed-gender groups). The results show that men’s foraging time accounted for 55% of the total foraging time for that period, during which they contributed 72% of the total kilocalories acquired.

One reviewer of this paper asked whether Martu women’s hunting might be better considered collecting, given that sand monitor hunting frequently involves digging prey from subsurface dens. We have dealt with this issue extensively elsewhere (Bliege Bird and Bird 2005, 2008; Bird et al. 2009). Martu women’s small game hunting is hunting because it involves a non-zero probability of pursuit failure owing to the prey’s mobility, and furthermore, it is emically defined as such (wartilpa, hunting, as opposed to nganyimpa, collecting). Even though sand goanna are seasonally burrowed, they do not become the animal equivalent of an underground plant storage organ: tubers don’t dig and move to elude capture, nor can they escape the hunter from a “pop hole.” When summer arrives, sand monitors must be tracked on the surface like any other mobile prey, and they are faster than humans over short distances (see Bird et al. 2009 for detailed description and analysis).

The adoption of technology that increases encounter rates may have a more profound effect on men’s relative contribution than changes in projectile technology. McCarthy and McArthur (1960) provide detailed data for 7 kangaroo hunting bouts around Fish Creek. These data show that men hunting kangaroo (M. rufus) on foot and with spear throwers had an average pursuit success rate of 0.25 and an average bout success rate of 0.86 (failing on only one of the seven bouts for which “focal follow” data was available). Martu men hunting kangaroo (M. robustus) on foot but with .22 gauge rifles have a similar pursuit success rate per focal follow (0.31) but a lower bout success rate (0.22; see Bird et al. 2009). Although the difference in bout success rates may be due to interspecies or ecological variation leading to differences in prey abundance, the similarity in pursuit success rates suggests that using rifles over spear throwers does not significantly increase pursuit success. When asked, Martu men even go so far as to suggest that more encounters end in success when a skilled hunter uses a spear thrower.

References

Altman, J. C. (1987). Hunter-gatherers today: An aboriginal economy in north Australia. Canberra: Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

Altman, J., & Peterson, N. (1988). Rights to game and rights to cash among contemporary Australian hunter-gatherers. In T. Ingold, D. Riches & J. Woodburn (Eds.), Hunters and gatherers: Property, power and ideology, pp. 75–94. Oxford: Berg.

Bell, D. (1993). Daughters of the dreaming. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Berndt, R. M., & Berndt, C. H. (1988). World of the first Australians: Aboriginal traditional life—past and present. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Bird, D. W., & Bliege Bird, R. (2005). Mardu children’s hunting strategies in the Western Desert, Australia: Foraging and the evolution of human life histories. In B. S. Hewlett & M. E. Lamb (Eds.), Hunter-gatherer childhoods, pp. 129–146. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Bird, D. W., & Bliege Bird, R. (in press). Competing to be leaderless: Food sharing and magnanimity among Martu aborigines. In J. Kantner, K. Vaughn & J. Eerkins (Eds.), The emergence of leadership: Transitions in decision-making from small-scale to middle-range societies. Santa Fe: SAR Press.

Bird, D. W., Bliege Bird, R., & Parker, C. (2005). Aboriginal burning regimes and hunting strategies in Australia’s Western Desert. Human Ecology, 33, 443–464.

Bird, D. W., Bliege Bird, R., & Codding, B. F. (2009). In pursuit of mobile prey: Martu hunting strategies and archaeofaunal interpretation. American Antiquity, 74, 3–29.

Bliege Bird, R. (2007). Fishing and the sexual division of labor among the Meriam. American Anthropologist, 109, 442–451.

Bliege Bird, R., & Bird, D. W. (2005). Human hunting seasonality. In D. Brockman & C. van Schaik (Eds.), Primate seasonality, pp. 243–266. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bliege Bird, R., & Bird, D. W. (2008). Why women hunt: Risk and contemporary foraging in a Western Desert Aboriginal community. Current Anthropology, 49, 655–693.

Bliege Bird, R., & Smith, E. A. (2005). Signaling theory, strategic interaction, and symbolic capital. Current Anthropology, 46, 221–248.

Bliege Bird, R., Smith, E. A., & Bird, D. W. (2001). The hunting handicap: Costly signaling in male foraging strategies. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, 50, 9–19.

Bliege Bird, R., Bird, D. W., Codding, B., Parker, C., & Jones, J. H. (2008). The fire stick farming hypothesis: Anthropogenic fire mosaics, biodiversity and Australian aboriginal foraging strategies. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (USA), 105(39), 14796–14801.

Boone, J. L. (1998). The evolution of magnanimity: When is it better to give than to receive? Human Nature, 9, 1–21.

Brand Miller, J., James, K. W., & Maggiore, P. M. A. (1993). Tables of composition of Australian Aboriginal foods. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Codding, B. F., & Jones, T. L. (2007). Man the show-off? Or the ascendance of a just-so-story: A comment on recent applications of costly signaling theory in American archaeology. American Antiquity, 72, 349–357.

Davenport, S., Johnson, P., & Yuwali. (2005). Cleared out: First contact in the Western Desert. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Devitt, J. (1988). Contemporary Aboriginal women and subsistence in remote, arid Australia. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Queensland.

Elston, R. G., & Zeanah, D. W. (2002). Thinking outside the box: A new perspective on diet breadth and sexual division of labor in the prearchaic Great Basin. World Archaeology, 34, 103–130.

Gould, R. A. (1967). Notes on hunting, butchering, and sharing of game among the Ngatajara and their neighbors in the west Australian desert. Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers, 36, 41–66.

Gould, R. A. (1969). Yiwara: Foragers of the Australian Desert. New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Gould, R. A. (1980). Living archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gould, R. A. (1991). Arid land foraging as seen from Australia: Adaptive models and behavioral realities. Oceania, 62, 12–33.

Gurven, M. (2004). To give or to give not: An evolutionary ecology of human food transfers. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 27, 543–583.

Gurven, M., & Kaplan, H. (2006). Determinants of time allocation across the lifespan: A theoretical model and an application to the Machiguenga and Piro of Peru. Human Nature, 17, 1–49.

Gurven, M., Allen-Arave, W., Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (2000). “It’s a wonderful life”: Signaling generosity among the Ache of Paraguay. Evolution and Human Behavior, 21, 263–282.

Hamilton, A. (1980). Dual social systems: Technology, labour and women’s secret rites in the eastern Western Desert. Oceania, 51, 4–20.

Hawkes, K. (1990). Why do men hunt? Some benefits for risky strategies. In E. Cashdan (Ed.), Risk and uncertainty in tribal and peasant economies, pp. 145–166. Boulder: Westview.

Hawkes, K. (1991). Showing off: Tests of an hypothesis about men’s foraging goals. Ethology and Sociobiology, 12, 29–54.

Hawkes, K. (1993). Why hunter-gatherers work: An ancient version of the problem of public goods. Current Anthropology, 34, 341–361.

Hawkes, K. (2000). Big game hunting and the evolution of egalitarian societies: Lessons from the Hadza. In M. Diehl (Ed.), Hierarchies in action: Cui bono? Center for Archaeological Investigations, Occasional Paper 27, pp. 59–83. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press.

Hawkes, K., O’Connell, J. F., & Blurton Jones, N. (1991). Hunting income patterns among the Hadza: Big game, common goods, foraging goals and the evolution of the human diet. Philosophical Transactions: Biological Sciences, 334, 243–251.

Hildebrandt, W. R., & McGuire, K. R. (2002). The ascendance of hunting during the California Middle Archaic: An evolutionary perspective. American Antiquity, 67, 231–256.

Hill, K., & Hawkes, K. (1983). Neotropical hunting among the Ache of eastern Paraguay. In R. Hames & W. Vickers (Eds.), Adaptive responses of native Amazonians, pp. 139–188. New York: Academic Press.

Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (1996). Ache life history. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Hill, K., Kaplan, H., Hawkes, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (1987). Foraging decisions among Aché hunter-gatherers: New data and implications for optimal foraging models. Ethology and Sociobiology, 8, 1–36.

Hurtado, A. M., Hill, K., Kaplan, H., & Hurtado, A. M. (1992). Trade-offs between female food acquisition and child care among Hiwi and Ache foragers. Human Nature, 3, 185–216.

Jochim, M. A. (1988). Optimal foraging and the division of labor. American Anthropologist, 90, 130–136.

Jones, T. L. (1996). Mortars, pestles, and division of labor in prehistoric California: A view from Big Sur. American Antiquity, 61, 243–264.

Jones, T. L., Porcasi, J., Gaeta, J., & Codding, B. F. (2008). The Diablo Canyon fauna: A coarse-grained record of trans-Holocene foraging from the central California mainland coast. American Antiquity, 73, 289–316.

Kaplan, H., Hill, K., & Hurtado, A. M. (1990). Risk, foraging, and food sharing among the Ache. In E. Cashden (Ed.), Risk and uncertainty in tribal and peasant economies, pp. 107–144. Boulder: Westview.

Kaplan, H., Hill, K., Lancaster, J., & Hurtado, A. M. (2000). A theory of human life history evolution: Diet, intelligence and longevity. Evolutionary Anthropology, 9, 156–185.

Kayberry, P. (1939). Aboriginal woman: Sacred and profane. London: Routledge.

Kieschnick, R., & McCullough, B. D. (2003). Regression analysis of variates observed on (0, 1): Percentages, proportions and fractions. Statistical Modeling, 3, 193–213.

Kuhn, S., & Stiner, M. C. (2006). What’s a mother to do? The division of labor among Neanderthals and modern humans in Eurasia. Current Anthropology, 47, 953–980.

Latz, P. (1996). Bushfires and bushtucker: Aboriginal plant use in Central Australia. Alice Springs: IAD.

Leacock, E. (1978). Women’s status in egalitarian society: Implications for social evolution. Current Anthropology, 19, 247–275.

Leacock, E. (1983). Interpreting the origins of gender inequality: Conceptual and historical problems. Dialectical Anthropology, 7, 263–284.

Lee, R. B. (1968). What hunters do for a living: Or, how to make out on scarce resources. In R. B. Lee & I. Devore (Eds.), Man the hunter, pp. 30–55. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Lee, R. B. (1979). The !Kung San: Men, women and work in a foraging society. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marlowe, F. W. (2003). A critical period for provisioning by Hadza men: Implications for pair bonding. Evolution and Human Behavior, 24, 217–229.

Marlowe, F. (2007). Hunting and gathering: The human sexual division of foraging labor. Cross-cultural Research, 41, 170–195.

McCarthy, F. D., & McArthur, M. (1960). The food quest and the time factor in Aboriginal economic life. In C. P. Mountford (Ed.), Records of the American-Australian Scientific Expedition to Arnhem Land, 2: Anthropology and nutrition, pp. 145–194. Melbourne: Melbourne University Press.

McGuire, K., & Hildebrandt, W. R. (1994). The possibilities of women and men: Gender and the California Milling Stone horizon. Journal of California and Great Basin Anthropology, 16, 41–59.

McGuire, K., & Hildebrandt, W. R. (2005). Rethinking Great Basin foragers: Prestige hunting and costly signaling during the Middle Archaic period. American Antiquity, 70, 695–712.

McGuire, K. R., Hildebrandt, W. R., & Carpenter, K. L. (2007). Costly signaling and the ascendance of no-can-do archaeology: A reply to Codding and Jones. American Antiquity, 72, 358–365.

Meehan, B. (1982). Shellbed to shellmidden. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Megitt, M. (1957). Notes on the vegetable foods of the Walpiri. Oceania, 28, 143–145.

Megitt, M. (1962). Desert people: A study of the Walbiri Aborigines of Central Australia. Sydney: Angus and Robertson.

Menard, S. (2002). Applied logistic regression analysis (second ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

O’Connell, J. F., & Hawkes, K. (1981). Alyawara plant use and optimal foraging theory. In B. Winterhalder & E. A. Smith (Eds.), Hunter-gatherer foraging strategies: Ethnographic and archaeological analyses, pp. 99–125. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

O’Connell, J. F., & Hawkes, K. (1984). Food choice and foraging sites among the Alyawara. Journal of Anthropological Research, 40, 504–535.

O’Connell, J. F., & Marshall, B. (1989). Analysis of kangaroo body part transport among the Alyawara of Central Australia. Journal of Archaeological Science, 16, 393–405.

O’Connell, J. F., Hawkes, K., & Blurton Jones, N. (1988). Hadza hunting, butchering, and bone transport and their archaeological implications. Journal of Anthropological Research, 44, 113–161.

R Development Core Team. (2008). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Roheim, G. (1974). The children of the desert: The western tribes of Central Australia. New York: Basic Books.

Sackett, L. (1979). The pursuit of prominence: Hunting in an Australian Aboriginal community. Anthropologica, 21, 223–246.

Sahlins, M. (1972). Stone Age economics. Chicago: Aldine.

SAS Institute. (2007). JMP, version 7. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc.

Scelza, B., & Bliege Bird, R. (2008). Group structure and female cooperative networks in Australia’s Western Desert. Human Nature, 19, 231–248.

Smith, E. A. (1991). Inujjuamiut foraging strategies: Evolutionary ecology of an Arctic hunting economy. New York: Aldine de Gruyter.

Smith, E. A., & Bliege Bird, R. (2005). Costly signaling and cooperative behavior. In H. Gintis, S. Bowles, R. Boyd & E. Fehr (Eds.), Moral sentiments and material interests: On the foundations of cooperation in economic life, pp. 115–148. Cambridge, MA: MIT.

Steward, J. H. (1938). Great Basin–Plateau aboriginal sociopolitical groups. Smithsonian Institution Bureau of American Ethnology, Bulletin 120. Washington D.C.

Tonkinson, R. (1974). The Jigalong mob: Aboriginal victors of the desert crusade. Menlo Park: Cummings.

Tonkinson, R. (1978). Semen vs spirit child in a Western Desert culture. In L. R. Hiatt (Ed.), Australian Aboriginal concepts, pp. 81–92. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Tonkinson, R. (1988a). Egalitarianism and inequality in a Western Desert culture. Anthropological Forum, 5, 545–558.

Tonkinson, R. (1988b). Ideology and dominations in Aboriginal Australia: A Western Desert test case. In T. Ingold, D. Riches & J. Woodburn (Eds.), Hunters and gatherers, 2: Property, power and ideology, pp. 150–164. Oxford: Berg.

Tonkinson, R. (1990). The changing status of Aboriginal women: “Free agent” at Jigalong. In R. Tonkinson & M. Howard (Eds.), Going it alone? Prospects for Aboriginal autonomy, pp. 125–148. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Tonkinson, R. (1991). The Mardu Aborigines: Living the dream in Australia’s Desert. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

Tonkinson, R. (2007). Aboriginal “difference” and “autonomy” then and now: Four decades of change in a Western Desert society. Anthropological Forum, 17, 41–60.

Tonkinson, R., & Tonkinson, M. (2001). “Knowing” and “being” in place in the Western Desert. In A. Anderson, I. Lilley & S. O’Connor (Eds.), Histories of old ages: Essays in honour of Rhys Jones, pp. 133–140. Canberra: Pandanus Books.

Veth, P. M. (1987). Martujarra prehistory: Variation in arid zone adaptations. Australian Archaeology, 25, 102–111.

Veth, P. M. (1989). Islands in the interior: A model for the colonisation of Australia’s arid zone. Archaeology in Oceania, 24, 81–92.

Veth, P. M. (1995). Aridity and settlement in North West Australia. Antiquity, 69, 733–746.

Veth, P. M. (2000). Origins of the Western Desert language: Convergence in linguistic and archaeological space and time models. Archaeology in Oceania, 35, 11–19.

Veth, P. M. (2005). Cycles of aridity and human mobility: Risk-minimization amongst late Pleistocene foragers of the Western Desert, Australia. In P. Veth, M. A. Smith & P. Hiscock (Eds.), Desert peoples: Archaeological perspectives, pp. 100–115. Oxford: Blackwell.

Veth, P. M., & Walsh, F. (1988). The concept of “staple” plant foods in the Western Desert region of Western Australia. Australian Aboriginal Studies, 2, 19–25.

Waguespack, N. M. (2005). The organization of male and female labor in foraging societies: Implications for early Paleoindian archaeology. American Anthropologist, 107, 666–676.

Walsh, F. (1990). An ecological study of traditional Aboriginal use of “country”: Martu in the Great and Little Sandy Deserts, Western Australia. Proceedings of the Ecological Society of Australia, 16, 23–37.

Wiessner, P. (2002). Hunting, healing and hxaro exchange: A long-term perspective on !Kung (Ju/’hoansi) large game hunting. Evolution and Human Behavior, 23, 407–436.

Winterhalder, B. (1981). Foraging strategies in the boreal forest: An analysis of Cree hunting and gathering. In B. Winterhalder & E. A. Smith (Eds.), Hunter-gatherer foraging strategies: Ethnographic and archaeological analyses, pp. 66–98. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Zeanah, D. W. (1996). Predicting settlement patterns and mobility strategies: An optimal foraging analysis of hunter-gatherer use of mountain, desert, and wetland habitats in the Carson Desert. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, University of Utah, Salt Lake City.

Zeanah, D. W. (2004). Sexual division of labor and central place foraging: A model for the Carson Desert of western Nevada. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology, 23, 1–32.

Acknowledgments

We owe an immense debt of gratitude to all Martu out at Punmu, Kunawarritji, and Parnngurr and the surrounding deserts, and especially to the Taylor and Morgan families. This paper benefited tremendously by suggestions and comments from James Holland Jones, Ian Robertson, Sarah Robinson, Eric Alden Smith, and two anonymous reviewers. Funding for this research was provided by the National Science Foundation, the Leakey Foundation, the Stanford Archaeology Center, and Stanford’s Department of Anthropology. Any mistakes in fact or judgment are the sole responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bliege Bird, R., Codding, B.F. & Bird, D.W. What Explains Differences in Men’s and Women’s Production?. Hum Nat 20, 105–129 (2009). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9061-9

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-009-9061-9