Abstract

Background

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most aggressive malignant tumors, with a poor long-term prognosis worldwide. The functional deregulations of global transcriptome were associated with the genesis and development of HCC, but lacks systematic research and validation.

Methods

A total of 519 postoperative HCC patients were included. We built an interactive and visual competing endogenous RNA network. The prognostic signature was established with the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator algorithm. Multivariate Cox regression analysis was used to screen for independent prognostic factors for HCC overall survival.

Results

In the training set, we identified a four-gene signature (PBK, CBX2, CLSPN, and CPEB3) and effectively predicted the overall survival. The survival times of patients in the high-score group were worse than those in the low-score group (p = 0.0004), and death was also more likely in the high-score group (HR 2.444, p < 0.001). The results were validated in internal validation set (p = 0.0057) and two external validation cohorts (HR 2.467 and 2.6). The signature (AUCs of 1, 2, 3 years were 0.716, 0.726, 0.714, respectively) showed high prognostic accuracy in the complete TCGA cohort.

Conclusions

In conclusion, we successfully built a more extensive ceRNA network for HCC and then identified a four-gene-based signature, enabling prediction of the overall survival of patients with HCC.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

According to the 2018 global cancer statistics, there are 841,080 new liver cancer cases and more than 780 thousand deaths per year worldwide, and China accounts for nearly half of the total number of cases and deaths [1, 2]. Approximately 70–90% of all primary liver cancers are hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) [3, 4].

The treatment of HCC has made encouraging progress over the past few decades and primarily consists of surgical resection, chemotherapy, molecular targeting treatment, and liver transplantation [5]. However, surgery remains the most effective treatment; it has markedly improved the overall survival (OS) of HCC patients, although the long-term survival rate is still low. Approximately 60% of patients experience recurrence or distant metastasis within 5 years [3]. Regarding the poor prognosis, many experts have identified several prognostic factors, including patient basic features (e.g., age and gender) and tumor-related factors (e.g., tumor grade), that can be used to predict the OS of HCC patients who have undergone surgery [6, 7]. However, effective prognostic factors are still lacking.

Although several studies have highlighted valuable biomarkers, these studies had limitations, including their inclusion of single-center cohorts, small populations, and single molecular markers. More importantly, most studies failed to validate their findings via another independent cohort, meaning that the results could not be generalized. Thus, few biomarkers have been utilized in clinical practice.

The competing endogenous RNA (ceRNA) hypothesis describes a novel regulatory mechanism by which mRNAs and long noncoding RNAs talk to each other using microRNA response elements (MREs) as letters to form a regulatory network across the whole transcriptome, which plays a significant role in cancer research [8, 9], such as in oral carcinoma [10] and cholangiocarcinoma [11]. Accordingly, there is a great need to explore the regulatory relationships between lncRNAs-miRNAs-mRNAs during HCC initiation and progression. Wang et al. identified a prognostic signature based on the expression profiles of six genes for the OS of HCC patients based on independent screening of Cox-penalized regressions [12]. To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there is still no report of the involvement of lncRNAs in the transcriptional regulation of miRNAs and mRNAs in the field of HCC with large-scale, high-throughput sequencing data.

In our study, we obtained lncRNA, mRNA and miRNA expression profiles and constructed the ceRNA network in HCC from the TCGA database. We identified 20 DEmRNAs involved in the ceRNA network that alone predicted the OS of HCC patients, termed “OS-genes”. Importantly, we conducted an integrated analysis of OS-genes using the logistic least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) penalized regression to generate a four-gene-based signature (PBK, CBX2, CLSPN, and CPEB3) associated with OS in HCC. Then, we validated this signature using the internal set and two external validation cohorts, analyzed it in subgroups of HCC patients, and showed that it was an independent indicator. Thus, we identified and validated a new candidate marker to predict HCC OS by classifying patients into low- and high-risk groups.

Materials and methods

Patients and data collection

We downloaded level 3 data, which contained the high-throughput sequencing data of mRNAs, lncRNAs and miRNAs of 374 HCC samples and 50 normal samples from the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA, https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/). Clinical data, such as prognosis and basic clinical information, were downloaded from the Data Coordinating Center (Supplementary Table S1).

The HCC patients were randomly assigned to a training set with N × q samples and an internal validation set with N × (1 − q) samples (q = 2/3). To validate our results responsibly, we searched for external validation cohorts from two independent centers. External validation cohort 1, GSE76427 (n = 115), microarray data and patient clinical information were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (GEO; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). In addition, we used another external validation cohort obtained from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital between January 1, 2010, and June 30, 2010, that included 50 postoperative HCC patients (the SYMH cohort or the qPCR validation cohort). All the clinicopathological features of external validation cohorts were presented in Supplementary Table S1. All diagnoses were confirmed by pathology. This retrospective analysis was approved by the institutional review board of Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital, Sun Yat-Sen University.

Identification of DEGs

DEGs, including differentially expressed mRNAs, lncRNAs and miRNAs (DEmRNAs, DElncRNAs, and DEmiRNAs), were identified among the 354 tumor tissues and 50 normal samples. The RNA expression data from TCGA were normalized. We conducted gene identification using the edgeR package in software R, which is publicly available through Bioconductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/) [13]. |log2 fold-change| ≥ 2 and p value < 0.05 were used for selecting DEmRNAs and DElncRNAs. We defined and annotated DElncRNAs using the Encyclopedia of DNA Elements (ENCODE); for DEmiRNAs, the select indicator was |log2 fold-change| ≥ 1.5 and the p value was < 0.05.

Seed match analysis and constructing the ceRNA network

The target mRNAs of DEmiRNAs were predicted by combined utilization in Targetscan database (http://www.targetscan.org/), miRDB database (http://www.mirdb.org/) and miRTarBase database (http://mirtarbase.mbc.nctu.edu.tw/). Then, we obtained the intersection elements between the target mRNAs and DEmRNAs, termed DEmiRNA-targeted DEmRNAs. We predicted the DElncRNAs targeted by DEmiRNAs in miRcode (http://www.mircode.org/). Cytoscape v3.5.0 software was used to build an interactive and visual ceRNA network using the Cytoscape user manual [14, 15].

Functional enrichment analysis, gene expression correlation analysis and survival analysis

We further studied the DEmRNAs using the ceRNA network, and we conducted functional enrichment analysis using the Database for Annotation, Visualization, and Integrated Discovery (DAVID) [16]. GO biological functions and KEGG pathways were chosen with an enrichment score > 1.5 as well as a significance level of p < 0.05. Then, we plotted the DERNA survival curves; these curves were called OS-genes, OS-lncRNAs and OS-miRNAs, respectively. In addition, 20 OS-gene expression correlations were assessed with the Pearson correlation indicator.

Prognostic signature screening and generation

To elucidate significant values for the 20 OS-genes, we used the logistic LASSO algorithm to select candidate OS-gene combinations that were reliably associated with HCC OS in the TCGA training set. LASSO allows the tuning of 25 parameters by fold cross-validation [17]. The risk score (RS) was calculated using the sum of the screened OS-gene expression values weighted by the coefficients from the LASSO regression model. We calculated the prognostic RS for each patient according to the following formula: RS = expressiongene1 × βgene1 + ··· + expressiongenen × βgenen (β: the regression coefficient derived from LASSO penalized regression) [18, 19].

Prognostic signature validation and evaluation

To validate the robustness of the prognostic signature, we generated the RS for each patient in the TCGA internal validation set and two external validation cohorts. We defined the median RS as the cutoff point, and HCC patients were divided into low- and high-risk groups. In addition, we used the univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses to evaluate the prognostic impact of clinicopathological features on OS. We calculated concordance indexes (c-indexes, also called HARRELL C-index), respectively. The c-index quantified the discrimination between two random patients, with a c-index of 0.5 indicating no discrimination and 1 indicating perfect discrimination. A time-dependent receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve analysis, with 1, 2, 3, and 5 years as the cutoff values of time, was also performed to compare the true positive and true negative rates of the OS prediction [20].

RNA extraction and real-time quantitative PCR

Fifty pairs of frozen HCC tissue and adjacent normal tissue were obtained from Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital. Total RNA was extracted using TRIzol reagent (Takara, Dalian, China). Reverse transcription was performed using PrimeScript RTase (Takara). The gene expression level was determined with qPCR with the help of Premix Ex Taq (Takara) and was normalized to GAPDH expression levels. We used the 2-ΔCT method to calculate expression levels. The primers were listed in Supplementary Table S2.

Statistical analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox regressions were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics Version 24, which was also used to generate hazard ratios (HRs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Kaplan–Meier survival curves were used to estimate OS in different groups, and the survival differences were assessed by a two-sided log-rank test in GraphPad Prism 5.0. LASSO penalized regression, and ROC curve analyses were conducted in software R version 3.3.4 with relevant packages, such as package survivalROC, gplots, and glmnet. All statistical tests were two-sided, and a p value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

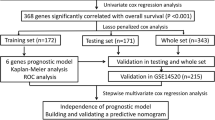

Study flowchart and clinical characteristics of patients

The study flowchart is presented in Fig. 1. A total of 354 HCC samples were included and were randomly divided into a training set (n = 236) and an internal validation set (n = 118). The median OS times of the patients in the TCGA training set, the TCGA validation set, the entire TCGA cohort, the GSE76427 cohort, and the SYMH cohort were 1694 (1068–2320), 1852 (883–2821), 1694 (1203–2185), 2296 (1534–3057) and 768 (554–981) days, respectively.

Differentially expressed genes and construction of the ceRNA network

A total of 1993 DEmRNAs were identified, including 1788 (89.71%) that were upregulated and 205 (10.29%) that were downregulated. In addition, we found 1071 differentially expressed lncRNAs, including 1014 (94.67%) upregulated and 57 (5.32%) downregulated DElncRNAs. However, we found only 162 (95.29%) upregulated and 8 (4.71%) downregulated DEmiRNAs. We generated a heat map and volcano with complete linkage clustering of DEmRNAs, DElncRNAs, and DEmiRNAs (Supplementary Figure S1).

To better understand how mRNA expression was regulated by lncRNA through combining miRNAs, we built a ceRNA visual network (Fig. 2a). According to seed match analysis, we found that 39 DEmRNAs were targets of the 20 DEmiRNAs, while 83 DElncRNAs interacted with the 20 DEmiRNAs (Supplementary Tables S3 and S4).

The ceRNA network of lncRNAs–miRNAs–mRNAs and functional analysis for DEmRNAs in HCC. To better understand how mRNA expression was regulated by lncRNA through combining miRNAs, we built a ceRNA visual network including 39 DEmRNAs, 83 DElncRNAs, and 20 DEmiRNAs from the TCGA database (a). Red represents upregulated DEGs, and blue represents downregulated DEGs. Foursquares: miRNAs, balls: mRNAs, diamonds: lncRNAs. To better elucidate the underlying pathways and biological mechanisms involved in the ceRNA network, we conducted GO (b) and KEGG pathway analyses (c) using the DAVID database for 39 DEmRNAs. DEmRNAs differentially expressed mRNAs

Functional enrichment and survival analyses of key ceRNAs

We conducted GO and KEGG pathway analyses using the DAVID database for 39 DEmRNAs (Fig. 2b, c). Many cancer-related GO items and KEGG pathways were significantly enriched, such as those associated with biological processes (e.g., cell proliferation and cell cycle) and pathways (e.g., hepatitis B and the p53 signaling pathway). Twenty mRNAs (OS-genes) (Supplementary Figure S2), one miRNA (miR-137), and 14 lncRNAs (OS-lncRNAs) (Supplementary Figures S3) were found to be significantly associated with OS. There was coexpression between 20 OS-genes; for example, the coexpression coefficient between CPEB3 and CCNB1 was − 0.57 (p < 0.001), whereas the coexpression coefficient between PBK and CCNB1 was 0.8 (Supplementary Figures S4I). In the future, the potential mechanisms underlying their correlations could be investigated.

Building a predictive signature from the TCGA training set

Twenty OS-genes were identified after we combined the DEmRNAs selected by the ceRNA network and survival analysis. We then used the LASSO regression model to further identify an optimal subset of gene-based signatures reliably associated with HCC OS in the TCGA training set. As a result, four genes were identified: PBK, CBX2, CLSPN, and CPEB3 (Fig. 3). To better clarify the performance of our predictive signature for HCC OS, we established RS with each gene coefficient weighted by the LASSO model. The RS was calculated for each patient in the training set as follows:

Construction of the integrated prognostic signature in the training set. a LASSO coefficient profiles of the 20 OS-genes. The vertical blue dotted lines are plotted at the value selected in b. b Selection of the tuning parameter (lambda) in the LASSO model by tenfold cross-validation based on minimum criteria for OS; the lower X axis shows log (lambda), and the upper X axis shows the average number of OS-genes. The Y axis indicates partial likelihood deviance error. Red dots represent average partial likelihood deviances for every model with a given lambda, and vertical bars indicate the upper and lower values of the partial likelihood deviance errors. The vertical black dotted lines define the optimal values of lambda, which provides the best fit. c, d Prognostic classifier analysis. c The RS distribution and survival time of each patient; 236 patients were divided into low- and high-risk groups according to the median RS value. d Heat map of the mRNAs in the prognostic signature. RS risk score

RS = (− 0.0922 × expression level of CPEB3) + (0.1215 × expression level of PBK) + (0.0128 × expression level of CBX2) + (0.0377 × expression level of CLSPN).

Effective prognostic signature in HCC patients

In the training set, 236 HCC patients were assigned to the low-score and high-score groups based on the median RS value (0.416). Patients in the high-score group exhibited worse survival than those in the low-score group as shown in Fig. 4a (p = 0.0004). In addition, survival analysis showed serum AFP, TNM stage, T stage, N stage, and M stage were found to be significantly associated with HCC OS (Supplementary Figure S5). We further investigated various subgroups of individual clinicopathological features in HCC patients and found that they were significantly correlated with OS because of imbalances between the high-score and low-score groups with respect to clinical features (Table 1). Subgroup analysis of the four-gene signature in the complete cohort was performed, and significant correlations between RS and OS were maintained in Asians (p < 0.001, Supplementary Figure S6A and S6B) and in patients whose serum AFP ≥ 20 ng/ml (p = 0.079, Supplementary Figures S6C and S6D), whereas RS value was associated with OS for the two subgroups of TNM stage and tumor grade (Supplementary Figures S6E-H).

Survival analysis and ROC analysis of the four-gene-based prognostic signature in independent cohorts. Comparison of overall survival times between the low- and high-risk groups in the five data sets. Time-dependent ROC curve comparison of the five data sets; AUCs at 1, 2, 3 and 5 years were calculated. TCGA training set (a, f); TCGA validation set (b, g); entire TCGA cohort (c, h); GSE76427 cohort (d, i); SYMH cohort (e, j). ROC receiver operating characteristic

Validating and evaluating the signature

Similar analyses demonstrated that the high-score group had a worse OS than that in the low-score group in the internal validation set (median OS, 1149 days versus 2131 days; p = 0.0389) (Fig. 4b). For the entire TCGA cohort of 354 patients, OS for the high-score patients was shorter than for the low-score patients (median OS, 1271 days versus 2132 days; p = 0.0016) (Fig. 4c). The median OS times for the low-score and high-risk groups were 2296 and 1759 days, respectively, although this difference was not statistically significant in GSE76427 external validation cohort (Fig. 4d). This pattern of another external validation cohort-SYMH data set was similar to that observed in the TCGA cohort (Supplementary Figure S4A-H). Similarly, patients with a low score generally had a better OS than patients with a high score and the median OS times of the two groups were 1825 and 695 days, respectively (p = 0.0476, Fig. 4e).

Cox proportional hazards regression analysis in validation cohorts

For the entire TCGA cohort, serum AFP, TNM stage, and the signature were significantly associated with HCC OS in the univariate analysis. A multivariate regression analysis indicated that TNM stage and signature were independent prognostic predictors of OS (Table 2). Furthermore, multivariate survival analysis showed that the four-gene signature could be an independent prognostic factor (HR 2.467, p = 0.021) in the GSE76427 cohort and was the only independent prognostic predictor of OS in the SYMH cohort (HR 2.6, p = 0.037) (Table 2).

Comparison with other prognostic factors

Time-dependent ROC curve analysis suggested that the four-gene signature was a stable predictor and even contained censored survival data (Fig. 4f–j).

In addition, the signature may achieve a more stable value in 2 years-OS prediction (Supplementary Tables S5). As shown in Supplementary Table S6, the signature incorporating four-genes expression achieved stable c-indexes in predicting HCC OS in the training and various validation sets (including internal and external validations).The signature was also significantly more specific and sensitive than other clinicopathological risk factors for the entire TCGA cohort and the two external validation cohorts (Supplementary Figure S7A-C). To develop a more reliable predictive model, we combined two independent prognostic factors; as a result, the four-gene signature and TNM stage (AUC 0.668, p < 0.05) had a more sensitive predictive value in the entire TCGA cohort (Supplementary Figure S7D). The combination of signature and TNM staging (or BCLC staging) had a higher AUC than the signature alone, although the difference was not significant for the GSE76427 cohort (Supplementary Figure S7E). However, for the SYMH cohort, there was no difference between the AUCs for the signature alone and the combination (Supplementary Figure S7F).

Discussion

More and more evidence demonstrates that genetic alterations and disorders in the signaling pathways are of significance in tumorigenesis and the progression of HCC, meaning that molecular markers are equally important in the prediction of HCC OS. Certainly, many molecular markers have been identified to predict HCC OS. Jin et al. found that SUOX (sulfite oxidase), as an independent prognostic factor of HCC, showed better associations with OS and TTR if combined with serum AFP in different cohorts [21]. Tao et al. found that BTBD7 expression combined with microvessel density could better predict HCC prognosis by Cox regression analysis [22]. However, most of the recent research has focused on single gene expression, a specific protein, lncRNAs or miRNAs. However, information is now rapidly emerging on the vital functional role of the molecular network in HCC initiation and progression, indicating that we should analyze the prognosis markers as a whole. But sometimes we have high-dimensional data. At the time, lasso regression was the selective method for improving prediction accuracy. Lasso has two important characteristics, one is feature selection: automatic selection of features, it will learn to remove features without information and precisely set the weights of these features to zero, especially for high-dimensional data. Another one is interpretability: models are easier to explain, for example, we can find the independent variables that provide the most important information in the model when we have a lot of independent variables [23,24,25,26]. Li et al. identified 13 differentially expressed miRNAs in the serum of HER2 + MBC patients with distinct responses to trastuzumab using miRNA microarrays and constructed a four-miRNA signature to predict survival using a LASSO model [27]. Backes et al. [28] used multivariable Lasso regression to develop models to identify patients most likely to benefit from adjuvant surgery by projecting their case–control data towards the entire cohort. Transcriptome profiling revealed an integrated signature, incorporating 15 mRNAs and three lncRNAs, was a powerful predictor of early relapse and had a better OS prediction than TNM staging in colon cancer [29].

In the present study, we conducted a comprehensive analysis of whole transcriptome resequencing data and its involvement in the prediction of HCC OS. First, we identified DEGs, including a total of 1993 differentially expressed mRNAs (DEmRNAs), 1071 differentially expressed lncRNAs and 170 DEmiRNAs. After building a ceRNA visual network, we found 39 DEmRNAs, 83 DElncRNAs and 20 DEmiRNAs. Some of them were reported to be cancer-related genes, such as CCNB1 [30], EZH2 [31, 32], AXIN2, [33] and FOXF2 [34]. We also found several significant HCC-associated lncRNAs in our ceRNA network, such as HOTAIR [35, 36] and HOTTIP [37]. Interestingly, we noticed that lncRNA LINC00221 interacted with 12 miRNAs. Thus, LINC00221 may serve as a key regulator. Next, we studied its specific biological functions and regulatory mechanisms in HCC. Notably, miR-137 was associated with HCC OS, and in the network, we found that its corresponding mRNA was PTGS2, a key oncogene in HCC [38]. Its candidate corresponding lncRNAs were HOTTIP, CLLU1, and GPC6-AS1. In the future, we will conduct an in-depth study of the regulatory mechanisms underlying the miRNA137-PTGS2-lncRNA network.

Subsequently, we identified a four-gene-based signature (weighted combination of PBK, CBX2, CLSPN, and CPEB3) and effectively predicted OS in HCC patients using LASSO penalized regression. PBK (PDZ-binding kinase) phosphorylates MAPKp38 and plays a crucial role in the activation of lymphoid cells. Phosphorylated PBK interacts with TP53, leading to TP53 destabilization and decreased expression following doxorubicin-related DNA damage [39, 40]. CBX2 (Chromobox protein homolog 2) was composed of multi-protein PRC1-like complex, which inhibited the transcriptional activities of many genes, including the HOX genes [41]. Although CBX2 has been less-studied in cancer research, the molecular profile of CBX2 suggested that it plays an oncogenic role [42]. CLSPN, which monitors the integrity of DNA replication forks, was essential for checkpoint-regulated cell cycle arrest in response to UV irradiation-induced DNA damage [43]. Choi et al. reported that CLSPN positively affected the survival of cancer cells and negatively affected the metastasis model in response to radiation [44]. CPEB3 (cytoplasmic polyadenylation element-binding protein 3) contains an intron-encoded self-cleaving ribozyme that is structurally and biochemically associated with human HDV ribozymes, regulating its own translation [45]. CPEB3 suppresses Stat5b-dependent EGFR gene transcription in neurons [46]. All four genes may serve as key regulatory genes for cell behaviors and functions, but their abstract functions have not yet been elucidated in HCC. In the future, we will conduct an in-depth study of the regulatory mechanisms for four genes (PBK, CBX2, CLSPN, and CPEB3) based on their ceRNA network clarified in present study.

Although we constructed an OS-related predictive model based on OS-related data, we surprisingly found that the model may also serve as a tool to forecast disease-free survival (DFS) to some extent (data are not shown), low score represents a long DFS, while high-score means that patient may suffer a poor DFS, but more cohort studies are needed to confirm this.

OS for HCC is multifactorial and cannot be only determined by gene expression. HCC development is driven by the interaction of genetic predisposition, environmental factors (metabolic syndrome, alcohol, and aflatoxin B1) and viruses (HBV and HCV). Hepatocarcinogenesis is a multi-step process, and driving forces in hepatocyte transformation, HCC development and progression are chronic inflammation, DNA damage, epigenetic modifications, senescence and telomerase reactivation, chromosomal instability, and early neoangiogenesis [47]. In the recent years, genome-wide technologies and next-generation sequencing have enabled the identification of molecular signatures to classify subgroups of HCCs and stratify patients according to prognosis. Unraveling the patterns of genomic alterations in HCCs is pivotal towards identifying targeted therapies [48, 49]. We tried to build a model based on genomic alterations which was associated with OS, and help us better formulate individual treatment and follow-up management strategies which meet the requirements of precision medicine to a certain extent. We could imagine two HCC patients: X and Y. They have the same age, sex, and BCLC stage. However, both patients are stratified into same stage of disease, which is associated with specific outcomes. As has been widely acknowledged, the two patients will probably have different prognoses, but the question regarding how to quantify these prognoses remains unresolved. In our model, we tried to calculate the total scores of the signature individually based on molecular medicine. Different scores correspond to different prognosis. If the patients have a higher score, we would maintain closer follow-up and medical treatment.

Similar to our investigation, Wang et al. identified a prognostic signature based on the expression profiles of six genes for the OS of HCC patients, including SRL, TTC26, CPSF2, TAF3, C16orf46, and CSN1S1, based on independent screening of Cox-penalized regressions [12]. Compared with previous studies, our study has several strengths. First, we used large-scale, high-throughput sequencing data from the TCGA database, rather than that from a single medical center, to avoid heterogeneity among different centers. Second, we established a lncRNA–miRNA–mRNA ceRNA network among the DEGs in tumor tissues and normal liver tissues. Third, we performed an in-depth screening study of DEmRNAs that were not only involved in the ceRNA network but also associated with the OS of HCC patients based on LASSO regression, in contrast to previous studies that used only one method to select prognostic markers. Fourth, we conducted internal validation and independent external validations, thus rendering the results more reliable and useful.

Survival analysis showed serum AFP, TNM stage, T stage, N stage, and M stage were found to be significantly associated with HCC OS. We further investigated various subgroups of individual clinicopathological features in HCC patients and found that they were significantly correlated with OS because of imbalances between the high-score and low-score groups with respect to clinical features. Significant correlations between signature and OS were maintained in Asians and in patients whose serum AFP ≥ 20 ng/ml. The four-gene signature was an independent prognostic factor in multivariate Cox regression and subgroup analysis, particularly for Asians patients with serum AFP ≥ 20 ng/ml.

Inevitably, our study had several limitations. First, the multivariable survival analysis contained only basic prognostic factors from the GEO database and was unable to suggest other possible clinical factors, such as status of the metastatic lesions and performance status of patients. Second, as we know, extensive evidence indicates that HCC is an extremely heterogeneous tumor at the genetic and molecular level, limited by the data of the study, all genes’ expression from TCGA, GEO, and SYMH cohorts were detected in a piece of HCC tissue from one patient. In the future, we will detect the expression of the four genes by single-cell whole-genome sequencing or quantitative RT-PCR analysis in several pieces of HCC specimens from one patient, so that we can know whether the four-gene signature is a reliable and workable OS prediction marker for HCC. In addition, we will seek for cooperation with other hospital to obtain more patients and tissues for the gene model validation.

Conclusions

We constructed a novel lncRNAs–miRNAs–mRNAs ceRNA network in HCC based on genome-wide analysis, then we identified and validated a new candidate therapeutic decision marker based on the ceRNA network that yields great promise in the prediction of HCC OS in the future.

Abbreviations

- HCC:

-

Hepatocellular carcinoma

- ceRNA:

-

Competing endogenous RNA

- TCGA:

-

The Cancer Genome Atlas

- DEGs:

-

Differentially expressed genes

- DERNA:

-

Differentially expressed RNA

- DEmRNA:

-

Differentially expressed mRNA

- DElncRNA:

-

Differentially expressed lncRNA

- DEmiRNA:

-

Differentially expressed miRNA

- LASSO:

-

Least absolute shrinkage and selector operation

- ROC:

-

Receiver operating characteristic

- OS:

-

Overall survival

- DFS:

-

Disease-free survival

- NGS:

-

Next-generation sequencing

- GEO:

-

Gene expression omnibus

- SYMH:

-

Sun Yat-sen Memorial Hospital

- GO:

-

Gene ontology

- KEGG:

-

Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- DAVID:

-

Database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery

- RS:

-

Risk score

- HR:

-

Hazard ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- AFP:

-

α-Fetoprotein

- TNM:

-

Tumor-lymph node-metastasis

- BCLC:

-

Barcelona Clinic Liver Cancer

References

Bray F, Ferlay J, Soerjomataram I, Siegel RL, Torre LA, Jemal A. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:394–424.

Chen W, Zheng R, Baade PD, et al. Cancer statistics in China, 2015. CA Cancer J Clin. 2016;66(2):115–32.

Bruix J, Gores GJ, Mazzaferro V. Hepatocellular carcinoma: clinical frontiers and perspectives. Gut. 2014;63(5):844–55.

Grandhi MS, Kim AK, Ronnekleiv-Kelly SM, Kamel IR, Ghasebeh MA, Pawlik TM. Hepatocellular carcinoma: from diagnosis to treatment. Surg Oncol. 2016;25(2):74–85.

El-Serag HB, Marrero JA, Rudolph L, Reddy KR. Diagnosis and treatment of hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2008;134(6):1752–63.

Roayaie S, Blume IN, Thung SN, et al. A system of classifying microvascular invasion to predict outcome after resection in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(3):850–5.

Cucchetti A, Vivarelli M, Piscaglia F, et al. Tumor doubling time predicts recurrence after surgery and describes the histological pattern of hepatocellular carcinoma on cirrhosis. J Hepatol. 2005;43(2):310–6.

Salmena L, Poliseno L, Tay Y, Kats L, Pandolfi PP. A ceRNA hypothesis: the Rosetta Stone of a hidden RNA language? Cell. 2011;146(3):353–8.

Tay Y, Kats L, Salmena L, et al. Coding-independent regulation of the tumor suppressor PTEN by competing endogenous mRNAs. Cell. 2011;147(2):344–57.

Li S, Chen X, Liu X, et al. Complex integrated analysis of lncRNAs-miRNAs-mRNAs in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Oral Oncol. 2017;73:1–9.

Song W, Miao DL, Chen L. Comprehensive analysis of long noncoding RNA-associated competing endogenous RNA network in cholangiocarcinoma. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;506(4):1004–12.

Wang Z, Teng D, Li Y, Hu Z, Liu L, Zheng H. A six-gene-based prognostic signature for hepatocellular carcinoma overall survival prediction. Life Sci. 2018;203:83–91.

Law CW, Alhamdoosh M, Su S, Smyth GK, Ritchie ME. RNA-seq analysis is easy as 1-2-3 with limma, Glimma and edgeR. F1000Res. 2016;5:1408.

Whelan C, Sonmez K. Computing graphlet signatures of network nodes and motifs in Cytoscape with GraphletCounter. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(2):290–1.

Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: a software environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–504.

Jiao X, Sherman BT, da Huang W, et al. DAVID-WS: a stateful web service to facilitate gene/protein list analysis. Bioinformatics. 2012;28(13):1805–6.

Qiu J, Peng B, Tang Y, et al. CpG methylation signature predicts recurrence in early-stage hepatocellular carcinoma: results from a multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(7):734–42.

Xu C, Fang J, Shen H, Wang YP, Deng HW. EPS-LASSO: test for high-dimensional regression under extreme phenotype sampling of continuous traits. Bioinformatics. 2018;34(12):1996–2003.

Gao J, Kwan PW, Shi D. Sparse kernel learning with LASSO and Bayesian inference algorithm. Neural Netw. 2010;23(2):257–64.

Heagerty PJ, Lumley T, Pepe MS. Time-dependent ROC curves for censored survival data and a diagnostic marker. Biometrics. 2000;56(2):337–44.

Jin GZ, Yu WL, Dong H, et al. SUOX is a promising diagnostic and prognostic biomarker for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2013;59(3):510–7.

Tao YM, Huang JL, Zeng S, et al. BTB/POZ domain-containing protein 7: epithelial-mesenchymal transition promoter and prognostic biomarker of hepatocellular carcinoma. Hepatology. 2013;57(6):2326–37.

Waldmann P, Ferencakovic M, Meszaros G, Khayatzadeh N, Curik I, Solkner J. AUTALASSO: an automatic adaptive LASSO for genome-wide prediction. BMC Bioinform. 2019;20(1):167.

Ren S, Huang S, Ye J, Qian X. Safe feature screening for generalized LASSO. IEEE Trans Pattern Anal Mach Intell. 2018;40(12):2992–3006.

Alhamzawi R, Ali HTM. The Bayesian adaptive lasso regression. Math Biosci. 2018;303:75–82.

Zhou L, Tang L, Song AT, Cibrik DM, Song PX. A LASSO method to identify protein signature predicting post-transplant renal graft Survival. Stat Biosci. 2017;9(2):431–52.

Li H, Liu J, Chen J, et al. A serum microRNA signature predicts trastuzumab benefit in HER2-positive metastatic breast cancer patients. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):1614.

Backes Y, Elias SG, Groen JN, et al. Histologic factors associated with need for surgery in patients with pedunculated T1 colorectal carcinomas. Gastroenterology. 2018;154(6):1647–59.

Dai W, Feng Y, Mo S, et al. Transcriptome profiling reveals an integrated mRNA-lncRNA signature with predictive value of early relapse in colon cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2018;39:1235–44.

Weng L, Du J, Zhou Q, et al. Identification of cyclin B1 and Sec62 as biomarkers for recurrence in patients with HBV-related hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical resection. Mol Cancer. 2012;11:39.

Gao SB, Xu B, Ding LH, et al. The functional and mechanistic relatedness of EZH2 and menin in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2014;61(4):832–9.

Cai MY, Tong ZT, Zheng F, et al. EZH2 protein: a promising immunomarker for the detection of hepatocellular carcinomas in liver needle biopsies. Gut. 2011;60(7):967–76.

Taniguchi K, Roberts LR, Aderca IN, et al. Mutational spectrum of beta-catenin, AXIN1, and AXIN2 in hepatocellular carcinomas and hepatoblastomas. Oncogene. 2002;21(31):4863–71.

Shi Z, Liu J, Yu X, et al. Loss of FOXF2 expression predicts poor prognosis in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23(1):211–7.

Li H, Tang XM, Liu Y, Li W, Chen Q, Pan Y. Association of functional genetic variants of HOTAIR with hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) susceptibility in a Chinese population. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;44(2):447–54.

Wu Y, Xiong Q, Li S, Yang X, Ge F. Integrated proteomic and transcriptomic analysis reveals long noncoding RNA HOX transcript antisense intergenic RNA (HOTAIR) promotes hepatocellular carcinoma cell proliferation by regulating opioid growth factor receptor (OGFr). Mol Cell Proteomics. 2018;17(1):146–59.

Quagliata L, Matter MS, Piscuoglio S, et al. Long noncoding RNA HOTTIP/HOXA13 expression is associated with disease progression and predicts outcome in hepatocellular carcinoma patients. Hepatology. 2014;59(3):911–23.

Chen H, Cai W, Chu ESH, et al. Hepatic cyclooxygenase-2 overexpression induced spontaneous hepatocellular carcinoma formation in mice. Oncogene. 2017;36(31):4415–26.

Hu F, Gartenhaus RB, Eichberg D, Liu Z, Fang HB, Rapoport AP. PBK/TOPK interacts with the DBD domain of tumor suppressor p53 and modulates expression of transcriptional targets including p21. Oncogene. 2010;29(40):5464–74.

Abe Y, Matsumoto S, Kito K, Ueda N. Cloning and expression of a novel MAPKK-like protein kinase, lymphokine-activated killer T-cell-originated protein kinase, specifically expressed in the testis and activated lymphoid cells. J Biol Chem. 2000;275(28):21525–31.

Vandamme J, Volkel P, Rosnoblet C, Le Faou P, Angrand PO. Interaction proteomics analysis of polycomb proteins defines distinct PRC1 complexes in mammalian cells. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2011;10(4):M110.002642.

Clermont PL, Sun L, Crea F, et al. Genotranscriptomic meta-analysis of the Polycomb gene CBX2 in human cancers: initial evidence of an oncogenic role. Br J Cancer. 2014;111(8):1663–72.

Chini CC, Chen J. Human claspin is required for replication checkpoint control. J Biol Chem. 2003;278(32):30057–62.

Choi SH, Yang H, Lee SH, Ki JH, Nam DH, Yoo HY. TopBP1 and Claspin contribute to the radioresistance of lung cancer brain metastases. Mol Cancer. 2014;13:211.

Salehi-Ashtiani K, Luptak A, Litovchick A, Szostak JW. A genomewide search for ribozymes reveals an HDV-like sequence in the human CPEB3 gene. Science. 2006;313(5794):1788–92.

Peng SC, Lai YT, Huang HY, Huang HD, Huang YS. A novel role of CPEB3 in regulating EGFR gene transcription via association with Stat5b in neurons. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38(21):7446–57.

Levrero M, Zucman-Rossi J. Mechanisms of HBV-induced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2016;64(1 Suppl):S84–101.

Nault JC, Zucman-Rossi J. Genetics of hepatocellular carcinoma: the next generation. J Hepatol. 2014;60(1):224–6.

Villanueva A, Llovet JM. Targeted therapies for hepatocellular carcinoma. Gastroenterology. 2011;140(5):1410–26.

Acknowledgements

Yongcong Yan: conceptualization, formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing-original draft. Yingjuan Lu: formal analysis, investigation, visualization, and writing-original draft. Kai Mao: investigation, visualization, and writing-original draft. Mengyu Zhang: investigation, methodology, and writing-review and editing. Haohan Liu: investigation and visualization. Qianlei Zhou: software and visualization. Jianhong Lin: data curation and methodology. Jianlong Zhang: methodology, resources, and supervision. Jie Wang: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, and writing-review and editing. Zhiyu Xiao: conceptualization, data curation, funding acquisition, investigation, methodology, project administration, resources, supervision, and writing-review and editing.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Nos. 81572407, 81602112, 81672405); Key project of Natural Science Foundation of Guangdong Province, China (No. 4210016041); Science and Technology Program of Guangdong Province, China (Nos. 2015A030313096, 2016A030313184); Natural Science Foundation of Guangzhou, China (No. 4250016043). Grant [2013] 163 from Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Molecular Mechanism and Translational Medicine of Guangzhou Bureau of Science and Information Technology; Grant KLB09001 from the Key Laboratory of Malignant Tumor Gene Regulation and Target Therapy of Guangdong Higher Education Institutes.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding authors

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

Yongcong Yan, Yingjuan Lu, Kai Mao, Mengyu Zhang, Haohan Liu, Qianlei Zhou, Jianhong Lin, Jianlong Zhang, Jie Wang and Zhiyu Xiao have no conflicts of interest for this study.

Ethical standards

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008. This study was approved by the institutional ethics committee of Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital and informed consent was obtained from all patients.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

12072_2019_9962_MOESM1_ESM.tif

Figure S1 Hierarchical clustering and volcano plots of DEGs. Hierarchical clustering of HCC tissues and normal live tissues by differentially expressed mRNAs (A), lncRNAs (C) and miRNAs (E). The lower horizontal axis represents samples, and the upper horizontal axis represents clusters of samples. The left vertical axis represents clusters of DEGs, and the right vertical axis represents DEG names. Red represents upregulated DEGs, and green represents downregulated DEGs. Volcano plots of differentially expressed mRNAs (B), lncRNAs (D) and miRNAs (F). The red dots represent upregulated DEGs, and the green dots represent downregulated DEGs. FDR, false discovery rate (TIFF 5915 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM2_ESM.tif

Figure S2 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 20 DEmRNAs (all were associated with the OS of HCC patients and were included in the ceRNA network). OS, overall survival (TIFF 4777 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM3_ESM.tif

Figure S3 Kaplan–Meier survival curves for 14 DElncRNAs and miRNA-137 (all were associated with OS of HCC patients and involved in the ceRNA network) (TIFF 11081 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM4_ESM.tif

Figure S4 The expression levels of the four genes in the signature and hierarchical clustering in the correlation matrix of 39 DEmRNAs involved in the ceRNA network. The expression levels of the four genes in the prognostic signature in the complete TCGA cohort and SYMH cohort. PBK (A, E), CBX2 (B, F), CLSPN (C, G), and CPEB3 (D, H). Pearson correlation analysis was used to calculate collinearity between the 20 OS-genes in the corresponding row and column (I) (TIFF 7362 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM5_ESM.tif

Figure S5 Kaplan–Meier survival curves stratified by age (A), gender (B), race (C), family history (D), serum AFP (E), invasion (F), fibrosis (G), grade (H), TNM (I), T stage (J), N stage (K), and M stage (L) (TIFF 9125 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM6_ESM.tif

Figure S6 Kaplan–Meier survival analysis for the low- and high-risk groups, stratified by race (A, B), serum AFP (C, D), TNM stage (E, F) and tumor grade (G, H) (TIFF 8329 kb)

12072_2019_9962_MOESM7_ESM.tif

Figure S7 Comparisons of the predictive values for OS of the four-gene-based signature and clinicopathological risk factors according to ROC analysis for 1 and 3 years (A–C). Comparisons of the predictive values for OS of the signature and a combination of the signature and important prognostic factors for independent cohorts (D–F). The AUC was calculated, and its 95% CI was estimated with bootstrap means. The P values were two-sided; HR hazard ratio; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval. (TIFF 10715 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Yan, Y., Lu, Y., Mao, K. et al. Identification and validation of a prognostic four-genes signature for hepatocellular carcinoma: integrated ceRNA network analysis. Hepatol Int 13, 618–630 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09962-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12072-019-09962-3