Abstract

Background

Burnout is a growing problem among medical professionals, reaching a crisis proportion. It is defined by emotional exhaustion, cynicism, and career dissatisfaction and is triggered by a mismatch between the values of the person and the demands of the workplace. Burnout has not previously been examined thoroughly in the Neurocritical Care Society (NCS). The purpose of this study is to assess the prevalence, contributing factors, and potential interventions to reduce burnout within the NCS.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of burnout was conducted using a survey distributed to members of the NCS. The electronic survey included personal and professional characteristic questions and the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI). This validated measure assesses for emotional exhaustion (EE), depersonalization (DP), and personal achievement (PA). These subscales are scored as high, moderate, or low. Burnout (MBI) was defined as a high score in either EE or DP or a low score in PA. A Likert scale (0–6) was added to the MBI (which contained 22 questions) to provide summary data for the frequencies of each particular feeling. Categorical variables were compared using χ2 tests, and continuous variables were compared using t-tests.

Results

A total of 82% (204 of 248) of participants completed the entire questionnaire; 61% (124 of 204) were burned out by MBI criteria. A high score in EE was present in 46% (94 of 204), a high score in DP was present in 42% (85 of 204), and a low score in PA was present in 29% (60 of 204). The variables feeling burned out now, feeling burned out in the past, not having an effective/responsive supervisor, thinking about leaving one’s job due to burnout, and leaving one’s job due to burnout were significantly associated with burnout (MBI) (p < 0.05). Burnout (MBI) was also higher among respondents early in practice (currently training/post training 0–5 years) than among respondents post training 21 or more years. In addition, insufficient support staff contributed to burnout, whereas improved workplace autonomy was the most protective factor.

Conclusions

Our study is the first to characterize burnout among a cross-section of physicians, pharmacists, nurses, and other practitioners in the NCS. A call to action and a genuine commitment by the hospital, organizational, local, and federal governmental leaders and society as a whole is essential to advocate for interventions to ameliorate burnout and care for our health care professionals.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Burnout is a growing problem among physicians and other medical professionals, reaching a crisis proportion. It is a psychological syndrome emerging as a health hazard for patient-centered professions. Health care professionals, particularly those in the critical care setting, require an intense level of commitment and a constant demand for personal contact with a huge emotional burden on practitioners who may be expected to go above and beyond the call of duty daily. In the past couple of years, the escalating trend for burnout is increasingly being acknowledged as the epidemic within the pandemic, necessitating immediate intervention.

Throughout the literature, burnout has been defined by high emotional exhaustion (EE), high depersonalization (DP), and low personal achievement (PA) (career dissatisfaction) [1, 2]. In the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases, an exclusive and broader definition of burnout was introduced, called “occupational burnout,” in which burnout is the result of working in a stressful work environment that is not well managed [3]. However, it is important to differentiate burnout from signs and symptoms of other conditions, such as anxiety, mood, behavioral disorders, and other medical conditions that could exacerbate it. Recent studies found that the most reported factors contributing to burnout were excessive bureaucratic tasks, lack of autonomy, and insufficient compensation and reimbursement [4,5,6,7]. Additional factors included difficulty maintaining work/life balance, long work hours, and lack of support from administrators, employers, and colleagues [8].

Whereas burnout exists throughout medicine, the prevalence varies among specialties. In 2013, the American Academy of Neurology Workforce Task Force found that demand for neurology services exceeded supply in most states and that by 2025, the demand would be even higher [6]. Neurology ranked as having the second highest burnout rate among all specialties at 50% in 2020, and specialties that have ranked among the top in burnout prevalence over the past 5 years include critical care at 44%, emergency medicine, family medicine, internal medicine, neurology, and urology [9].

Although the existing literature gives us an idea about the prevalence of burnout among US physicians and potential contributing factors, the international Neurocritical Care Society (NCS) was not previously studied [8]. Hence, in this work, we aim to estimate the prevalence of burnout in the NCS, assess the factors associated with burnout, outline potential strategies to prevent or mitigate burnout, and establish engagement and a call to action within the NCS and the entire health care system.

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional study of burnout was conducted in 2016 by creating and distributing a questionnaire to neurocritical care practitioners who were members of the NCS. Members include attending physicians, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, registered nurses, pharmacists, fellows, and residents. Qualtrics was used to create and manage the survey (Qualtrics Labs, Inc). Following its approval, the survey was available online on the NCS website for approximately 6 months in 2016, and the study was also granted approval by the Tufts Medical Center Institutional Review Board.

The survey consisted of 26 questions in two parts. The first part consisted of 25 questions related to demographics, professional characteristics, and potential factors associated with burnout. The second part (i.e., 26th question) was the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel (MBI), which contained separate 22 questions about job-related feeling. The MBI is considered the gold standard validated tool for measuring burnout [1, 2]. It has three subscales: EE, DP, and PA. The EE scale assesses feeling emotionally overwhelmed and exhausted by one’s work. The DP scale measures a state of psychological withdrawal from relationships and the development of a negative, cynical, and callous attitude. The PA scale assesses feelings of competence and achievement in one’s work with people [1]. Burnout is defined on a continuum from low to high, depending on the score in each of the subscales. Previous studies defined burnout (MBI) by including only a high score in EE, a high score in DP, or a low score in PA. Similar to previous studies [10, 11], we included high scores in EE, high scores in DP, or low scores in PA. Burnout (MBI) was defined in our study as having one of the following: a score > 27 on the EE subscale, a score > 10 on the DP subscale, or a score < 33 on the PA subscale. A Likert scale (0–6) was added to the MBI (which contained 22 questions) to provide summary data for the frequencies of each particular feeling. Only the respondents with a complete set of answers were included in the analysis; whereas respondents with missing data were excluded from the study.

Statistical analyses

Standard descriptive statistics are presented to characterize participants and summarize the MBI burnout scores, with continuous variables reported as mean and standard deviation or median and interquartile range according to data normality and categorical variables reported as whole numbers and proportions. Using the scoring provided in the MBI manual, we calculated the percentage of participants with high EE and DP and low PA. Associations with MBI burnout among variables of interest were evaluated through the χ2 test for categorical variables and the t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test, as appropriate, for continuous variables. All the presented analyses were performed using the STATA 17.0 software (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and a two-sided p value was set at < 0.05 for statistical significance.

Results

Baseline demographics

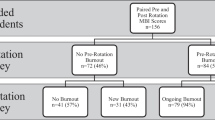

The survey was sent to approximately 2000 members of the NCS. A total of 204 of 248 (82.3%) respondents completed the entire survey and were included in our final analysis. The remaining 44 respondents with missing survey answers were excluded from the analysis. Of the 204 final respondents, 57% were male, 70% were married, and 54% had children under the age of 18 in the household, and a majority of respondents were attending physicians (63%). There was no significant association between burnout and sex (p = 0.2) or different marital statuses (p = 0.1).The descriptive characteristics of the study sample are presented in Table 1.

MIB results

The MBI subscales median, interquartile range, and percentages are detailed in Table 2; 46% (94 of 204) scored high for EE, 42% (85 of 204) scored high for depersonalization, and 29% (60 of 204) scored low for PA, any one of which would qualify as burnout (MBI) per our predetermined definition. Overall, 61% (124 of 204) of participants were identified as having burnout by MBI criteria.

Factors associated with burnout

In addition to measuring burnout (MBI), we directly asked the respondents about potential questions associated with burnout. The association between some burnout survey answers and burnout (MBI) was explored (Table 3). For simplification, either the “yes” or the “no” row of the dichotomized survey question is shown. When evaluated individually, respondent factors that were significantly associated with burnout (MBI) were the following: feeling burned out now (68% vs. 16%; p < 0.001), feeling burned out in the past (87% vs. 74%; p = 0.01), the perception of having an ineffective supervisor (48% vs. 21%; p < 0.001), thinking of leaving one’s current job due to feeling burned out (42% vs. 8%; p < 0.001), and having left one’s job due to burnout (23% vs. 10%; p = 0.02).

Another comparison was made between some categorized survey questions and burnout (MBI) (Table 4). More hours per day spent in the hospital on service was associated with statistically significant higher burnout rates (74 of 107 [69.2%] with ≥ 11 h/day vs. 50 of 97 [51.5%] with ≤ 10 h/day; p = 0.01). There was a higher percentage of burnout in younger providers with less time in practice (76 of 118 [64.4%] providers with ≤ 10 years in practice vs. 48 of 86 [55.8%] providers with > 10 years in practice); however, the difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.1). Similarly, higher burnout rates were noted in providers with less time in their jobs (102 of 163 [62.6%] providers with ≤ 10 years in their current job vs. 22 of 41 [53.7%] providers with > 10 years in their current job; p = 0.2). Moreover, a higher burnout percentage was noted with increased number of patients seen per day (77 of 118 [65.3%] in the group seeing ≥ 11 patients per day vs. 47 of 86 [54.7%] in the group seeing ≤ 10 patients per day; p = 0.1).

Burnout precipitating/alleviating factors

Respondents were asked to identify from a list of factors those that they believed contributed to or alleviated their burnout. The most reported reason for burnout was insufficient support staff (49%) (Fig. 1), whereas improved workplace autonomy was the most cited alleviating factor (46%) (Fig. 2).

Discussion

The prevalence of burnout among neurointensivists in the United Sates has not been studied before. Our survey is the first to characterize burnout among a cross-section of physicians of all levels of practice as well as pharmacists, nurses, and other practitioners in the NCS. We found that 61% of all respondents and 62% of the attending physicians met criteria for burnout defined by the MBI. Also, respondents who feel burned out now, who felt burn out in the past, and who left their job due to feeling burned out were associated with burnout defined by the MBI. Moreover, the perception of having an effective and responsive supervisor was significantly protective against burnout (Table 5).

The toll of health care professionals’ burnout is multifold on the individual level and organizational level, as well as the health care system, which would constitute a tremendous burden. Whereas burnout exists throughout medicine, the prevalence tends to vary between different career stages as well as specialty. In line with prior reports [12], we found higher burnout rates among practitioners in the early-to-middle phases of their careers compared with the senior practitioners in later career stages, although the difference was not statistically significant. This is likely multifactorial. Senior neurointensivists may only seem less inclined to burnout because those prone to burnout have already left the profession or retired, leaving only those with more robust coping abilities remaining. Also, senior neurointensivists may have more experience in the health care system and thus are more resilient to burnout and able to easily adapt to ongoing changes. This contrasts with neurointensivists early in practice, who are more likely to be younger and have less autonomy, less flexible work hours, longer shifts, and younger children.

In terms of specialty, neurology is one of the specialties with both a high burnout rate and low career satisfaction amid the unrelenting demand for acute neurological care and high prevalence of chronic neurological disorders among the general population [6, 9, 13]. Previous studies have reported a significant increase in physician turnover rates as well as malpractice lawsuits from medical errors associated with burned-out physicians [9, 11], which would translate into higher costs and burden for the hospitals and the entire health care system. Moreover, two studies published in 2017 found that 66% of attending neurologists, 73% of neurology residents, and 55% of neurology fellows reported experiencing at least one symptom of burnout [14, 15]. With the anticipated increase in the neurologist shortage, from 11% in 2012 to 19% by 2025 [16], an expected increase in the weekly working hours of the remaining staff would ensue, potentially hindering an adequate patient–physician relationship as well as detracting the health care professionals from their sense of autonomy and personal accomplishment. Eventually, all of this would result in increased neurologist attrition and a subsequent downward spiral of augmented burnout among the neurology workforce, including the NCS.

In the myopic view of delivering high-quality, multidisciplinary, coordinated care by companionate health care professionals, we often fail to recognize the “cost of caring” on them. In comparison to other professions, burnout is relatively high among critical care physicians [17,18,19]. The Critical Care Societies Collaborative in 2016 published a call to action that focused on burnout syndrome in the critical care setting and urged stakeholders to raise awareness and help mitigate the ramifications of it on both the critical care professionals and patients [17]. In a systematic review of critical care physicians, burnout prevalence was high at 70% [20], and in a French cross-sectional survey in 189 intensive care units, up to 46% of critical care physicians reported high burnout symptoms [21]. Furthermore, in a US single-center study of neurocritical care unit staff, high scores on the burnout subscales EE and DP were reported among nurses [8], and in another study of intensive care unit nurses, 86% met the criterion of burnout [22].

Burnout impacts the physician’s life quality and the quality of care delivered to the patient. Burned-out practitioners may be less interested in their work, less sympathetic with their patients, and more likely to misdiagnose or overlook subtle medical clues, which could lead to medical errors and negative consequences [23]. They may resort to maladaptive behaviors to cope with the stress, such as substance abuse, personal detachment, and even suicide. Several studies showed that burned-out practitioners experience higher rates of depression, work/home conflicts, substance abuse, and suicide [13, 14, 24]. A meta-analysis found that physicians had a higher risk for suicide compared with the general population [25]. Another study showed that only 32.3% of neurologists reported that their work schedules left some time for their personal lives compared with 40.9% for other physicians [6]. Ultimately, burnout affects not only the physicians’ lives but also the lives of the people close to them, underscoring its nature as not just a work-related problem [26, 27]. In our survey, we found that current feeling of burnout and leaving the current job due to burnout were the strongest predictors of having burnout on the MBI. Similar to prior work [7], the perception of having an effective and/or responsive supervisor was protective against burnout. Moreover, adequate financial compensation and reimbursement is a major part of job satisfaction and professional well-being. In a burnout survey among neurointerventionalists, additional compensation was significantly protective against burnout [28]. Nonetheless, other elements may influence well-being and job satisfaction at different career phases.

Neurological diseases are one of the predominant causes of morbidity and mortality worldwide. The global burden of neurological disorders has increased substantially over the past 25 years. The number of deaths from neurological diseases has increased by 36.7% between 1990 and 2015, and disability-adjusted life years have increased by 7.4% [29]. The disability-adjusted life years from all neurological disorders combined are higher than those from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and substance-use disorders [30]. The ramifications of such a burden require careful planning to ensure the availability of adequate providers and appropriate funding amounts. Although the US spends a large proportion of its gross domestic product on health care, the amount is disproportionately low for neurological conditions according to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS), concurrent with decreasing neurology reimbursements progressively over time [30,31,32,33]. In the yearly CMS-sponsored proposed regulations for physicians’ reimbursements, the 2022 Physician Fee Schedule does not provide big changes in reimbursements; however, it will enable neurologists to get paid for services that were previously not covered [34]. The American Academy of Neurology is supportive of the new changes but has pointed out that the increases are being offset by cuts to other services, primarily hospital-based procedural services (inpatient and outpatient) [35]. The lack of appropriate funding is compounded by the conventional misconception in many health care organizations that burnout is solely the individual’s responsibility [36]. This usually results in limited strategies that target individual-level factors while ignoring higher-level factors that are the most cited drivers of physician burnout. There is a strong correlation between physician well-being and the success of an organization. Hospital administrators should implement various strategies to reduce physician burnout and create a less stressful working environment. First, acknowledging the problem and demonstrating that the organization cares about the well-being of its providers is essential. Once identified, burnout should be assessed routinely. Measures can include regular evaluations of burnout, professional satisfaction, and emotional health, fatigue, and/or stress, in addition to the hospital patient volume, patient satisfaction, financial reimbursements, and quality/safety care metrics, which most hospitals in the United States regularly measure. Second, cultivating a shared responsibility approach to burnout on multiple levels (individual, hospital, organizational, federal) can make a positive impact. Engagement is a positive work-related state of fulfillment that is characterized by vigor, dedication, and absorption and is the countermeasure act to fight burnout [37]. Previous studies have proven that promoting engagement on multiple levels in the health care organization is associated with lower burnout risk [38, 39]. For example, the Mayo Clinic’s experience at implementing nine organizational-level efforts to reduce burnout and promote engagement was a success. In 2015, they decreased the absolute burnout rate by 7% within 2 years after executing several organizational changes [38]. In addition, as the COVID-19 pandemic continues, the burden of burnout will likely escalate, and the well-being of our physicians and frontline health care workers should not be overlooked. Amid the COVID-19 pandemic crisis in 2020, which will only worsen the existing burnout crisis, Dzau et al. [38] suggested high-priority actions to protect clinicians’ well-being during and after COVID-19, which might be helpful for the health care systems to adopt. The reported rates of burnout, depression, and insomnia have escalated tremendously in health care frontline workers during the pandemic [40], and future research should provide more insight into the impact of the pandemic on neurocritical care staff.

Our survey study is limited by inherent limitations of online-based survey studies, including recall and selections biases. The surveyed sample included respondents from the United States and outside countries, representing a cross-section of physicians of all levels of training and practice and pharmacists and nurses. However, sample size remains a limitation despite capturing about 20% of NCS members. An element of selection bias cannot be entirely excluded given the inability to capture neurointensivists who were not members of the NCS. Furthermore, the survey questions did not capture the practice settings of the respondents (e.g., academic vs. private) or their original specialty (e.g., neurology vs. anesthesia), which might influence the results. Moreover, nonresponse bias might exist in that nonrespondents’ choices might differ from those of respondents because the most burned-out health care providers might be more likely to complete the survey compared with their non-burned-out counterparts. Also, a fourth edition of the MBI questionnaire was published in 2018; however, we used the third edition because our survey was conducted earlier. Finally, this survey was conducted prior to the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which might limit extrapolation of its findings to the current era, and futures studies remain warranted to examine this in further detail.

Conclusions

This survey of the NCS demonstrated a high burnout prevalence of about 61%. Burnout defined by MBI criteria was more prevalent in early to mid-career than in late-career practice years. Feeling burned out now, leaving one’s job due to burnout, and working for long hours (11 h or more) were significantly associated with burnout (MBI). The NCS is an international organization, and there may be variability in factors that contribute to and alleviate burnout between different countries. A call to action and a real commitment by the hospital, organizational, local, and federal governmental leaders and even society as whole is essential to advocate for interventions to ameliorate burnout and protect and care for our society’s health care professionals.

References

Maslach C, Jackson SE. The measurement of experienced burnout. J Organ Behav. 1981;2(2):99–113.

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP. Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education; 1997.

Burn-out an "occupational phenomenon": International Classification of Diseases. 2019.

Shanafelt TD, Balch CM, Bechamps G, Russell T, Dyrbye L, Satele D, et al. Burnout and medical errors among American surgeons. Ann Surg. 2010;251(6):995–1000. https://doi.org/10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181bfdab3.

Shanafelt TD, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Hasan O, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Relationship between clerical burden and characteristics of the electronic environment with physician burnout and professional satisfaction. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(7):836–48. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.05.007.

Shanafelt TD, Hasan O, Dyrbye LN, Sinsky C, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Changes in burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance in physicians and the general US working population between 2011 and 2014. Mayo Clin Proc. 2015;90(12):1600–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2015.08.023.

West CP, Dyrbye LN, Shanafelt TD. Physician burnout: contributors, consequences and solutions. J Intern Med. 2018;283(6):516–29. https://doi.org/10.1111/joim.12752.

Purvis TE, Saylor D. Burnout and resilience among neurosciences critical care unit staff. Neurocrit Care. 2019;31(2):406–10. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-019-00822-4.

Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, Dyrbye LN, Sotile W, Satele D, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377–85. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199.

Thomas NK. Resident burnout. JAMA. 2004;292(23):2880–9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.292.23.2880.

Shanafelt TD, Bradley KA, Wipf JE, Back AL. Burnout and self-reported patient care in an internal medicine residency program. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(5):358–67. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-5-200203050-00008.

Dyrbye LN, Varkey P, Boone SL, Satele DV, Sloan JA, Shanafelt TD. Physician satisfaction and burnout at different career stages. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(12):1358–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2013.07.016.

Sigsbee B, Bernat JL. Physician burnout: a neurologic crisis. Neurology. 2014;83(24):2302–6. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000001077.

Busis NA, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, Levin KH, Schwarz HB, Molano JR, et al. Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurologists in 2016. Neurology. 2017;88(8):797–808. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000003640.

Levin KH, Shanafelt TD, Keran CM, Busis NA, Foster LA, Molano JRV, et al. Burnout, career satisfaction, and well-being among US neurology residents and fellows in 2016. Neurology. 2017;89(5):492–501. https://doi.org/10.1212/wnl.0000000000004135.

Dall TM, Storm MV, Chakrabarti R, Drogan O, Keran CM, Donofrio PD, et al. Supply and demand analysis of the current and future US neurology workforce. Neurology. 2013;81(5):470–8. https://doi.org/10.1212/WNL.0b013e318294b1cf.

Moss M, Good VS, Gozal D, Kleinpell R, Sessler CN. An official critical care societies collaborative statement: burnout syndrome in critical care healthcare professionals: a call for action. Crit Care Med. 2016;44(7):1414–21. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000001885.

Pastores SM, Kvetan V, Coopersmith CM, Farmer JC, Sessler C, Christman JW, et al. Workforce, workload, and burnout among intensivists and advanced practice providers: a narrative review. Crit Care Med. 2019;47(4):550–7. https://doi.org/10.1097/ccm.0000000000003637.

Mikkelsen ME, Anderson BJ, Bellini L, Schweickert WD, Fuchs BD, Kerlin MP. Burnout, and fulfillment, in the profession of critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019;200(7):931–3. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201903-0662LE.

van Mol MM, Kompanje EJ, Benoit DD, Bakker J, Nijkamp MD. The prevalence of compassion fatigue and burnout among healthcare professionals in intensive care units: a systematic review. PLoS ONE. 2015;10(8):e0136955. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0136955.

Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, Kentish N, Pochard F, Loundou A, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175(7):686–92. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC.

Mealer M, Burnham EL, Goode CJ, Rothbaum B, Moss M. The prevalence and impact of post traumatic stress disorder and burnout syndrome in nurses. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(12):1118–26. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20631.

Motluk A. Do doctors experiencing burnout make more errors? CMAJ Can Med Assoc J journal de l'Association medicale canadienne. 2018;190(40):E1216–e7. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.109-5663.

Kane L: Medscape national physician burnout & suicide report 2020: the generational divide. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460#2. Accessed 12 Jan 2020.

Schernhammer ES, Colditz GA. Suicide rates among physicians: a quantitative and gender assessment (meta-analysis). Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(12):2295–302. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2295.

Center C, Davis M, Detre T, Ford DE, Hansbrough W, Hendin H, et al. Confronting depression and suicide in physicians: a consensus statement. JAMA. 2003;289(23):3161–6. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.289.23.3161.

Oreskovich MR, Kaups KL, Balch CM, Hanks JB, Satele D, Sloan J, et al. Prevalence of alcohol use disorders among American surgeons. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):168–74. https://doi.org/10.1001/archsurg.2011.1481.

Fargen KM, Arthur AS, Leslie-Mazwi T, Garner RM, Aschenbrenner CA, Wolfe SQ, et al. A survey of burnout and professional satisfaction among United States neurointerventionalists. J Neurointerv Surg. 2019;11(11):1100–4. https://doi.org/10.1136/neurintsurg-2019-014833.

Schedule NTMPF. 2022.

Martin AB, Hartman M, Washington B, Catlin A. National health care spending in 2017: growth slows to post-great recession rates; share of GDP stabilizes. Health affairs (Project Hope). 2019;38(1):101377hlthaff201805085. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2018.05085.

Anderson P: Medicare payments: Where do neurologists stand? 2015. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/842524.

Avitzur O. Is declining reimbursement forcing neurology into extinction? Neurol Today. 2004;4(1):54–9.

Stat O. Health expenditure and financing; 2019. https://stats.oecd.org/index.aspx?DataSetCode=SHA.

Services CMS: CY 2022 physician fee schedule.

Neurology TAA: 2022 Medicare physician fee schedule. 2022.

Scheurer D, McKean S, Miller J, Wetterneck TUS. physician satisfaction: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):560–8. https://doi.org/10.1002/jhm.496.

Schaufeli WB, Salanova M, González-Romá V, Bakker AB. The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. J Happiness Stud. 2002;3(1):71–92.

Dzau VJ, Kirch D, Nasca T. Preventing a parallel pandemic—a national strategy to protect clinicians’ well-being. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):513–5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2011027.

Shanafelt TD, Noseworthy JH. Executive leadership and physician well-being: nine organizational strategies to promote engagement and reduce burnout. Mayo Clin Proc. 2017;92(1):129–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.10.004.

Zhang C, Yang L, Liu S, Ma S, Wang Y, Cai Z, et al. Survey of insomnia and related social psychological factors among medical staff involved in the 2019 novel coronavirus disease outbreak. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:306. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00306.

Funding

None.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

PEA contributed to data acquisition, design and conduction of data analysis, interpretation of the analyzed data, drafting the abstract/manuscript and revising it, and submission of the final version of manuscript after all authors read and approved it. MMS contributed to data design, conduction of data analysis, interpretation of the analyzed data, and drafting the abstract/manuscript and revising it. YA contributed to survey design and conduction and data collection and analysis. LL contributed to survey design and conduction, data collection and analysis, and drafting the manuscript and revising it. DMG-L, senior author, contributed to all aspects of the manuscript. She has full access and permission to collect and disclose the Maslach Burnout Inventory Human Services Survey for Medical Personnel. She contributed to survey design and conduction, data collection and analysis, interpretation of the analyzed data, and drafting the abstract/manuscript and revising it.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Ethical approval/informed consent

The authors confirm adherence to ethical guidelines and institutional review board approval from Tufts Medical Center.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Aboutaleb, P.E., Salem, M.M., Adibnia, Y. et al. A Survey of Burnout Among Neurocritical Care Practitioners. Neurocrit Care 40, 328–336 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01750-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12028-023-01750-0