Abstract

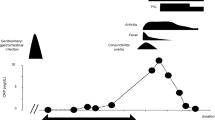

Reactive arthritis (ReA) occurs after a preceding bacterial infection of the urogenital or gastroenteral tract. The bacteria triggering ReA persist in vivo and seem to be responsible for triggering an immune response. A cytokine imbalance with a relative lack of T-helper 1 cytokines may play an important role allowing these bacteria to survive. This seems to be relevant for manifestation and chronicity of the arthritis. For the chronic cases and cases evolving into ankylosing spondylitis, the interaction between bacteria and human leukocyte antigen B27 plays an additional crucial role. Among others, the arthritogenic peptide hypothesis is one way to explain this association. Human leukocyte antigen B27-restricted peptides from Yersinia and Chlamydia, which are stimulatory for CD8+ T cells derived from patients with ReA, have been identified. The exact role of such peptides for the pathogenesis of ReA and other spondyloarthritides still has to be defined.

Similar content being viewed by others

References and Recommended Reading

Sieper J, Braun J, Kingsley GH: Report on the Fourth International Workshop on Reactive Arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43:720. This gives a good overview on ReA based on the discussion during the most recent ReA workshop.

Granfors K, Märker-Hermann E, De Keyser P, et al.: The cutting edge of spondyloarthropathy research in the millennium. Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46:606. This gives an overview on the whole group of spondyloarthropathies, including ReA, and the pathogenetic links between the single diseases.

Toivanen A: Reactive arthritis: clinical features and treatment. In Rheumatology, edn 3. Edited by Hochberg M, Silman A, Smolen J, et al. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2003:1233–1240.

Keat AC, Maini RN, Nkwazi GC, et al.: Role of Chlamydia trachomatis and HLA-B27 in sexually acquired reactive arthritis. BMJ 1978, 1:605–607.

Buchs N, Chevrel G, Miossec P: Bacillus Calmette-Guerin induced aseptic arthritis: an experimental model of reactive arthritis. J Rheumatol 1998, 25:1662–1665.

Braun J, Laitko S, Treharne J, et al.: Chlamydia pneumoniae: a new causative agent of reactive arthritis and undifferentiated oligoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 1994, 53:100–105.

Zhang Y, Gripenberg-Lerche C: Antibiotic prophylaxis and treatment of reactive arthritis: lessons from an animal model. Arthritis Rheum 1996, 39:1238–1243.

Granfors K, Jalkanen S, von Essen R, et al.: Yersinia antigens in synovial-fluid cells from patients with reactive arthritis. N Engl J Med 1989, 320:216–221.

Ugrinovic S, Mertz A, Wu P, et al.: A single nonamer from the Yersinia 60-kDa heat shock protein is the target of HLA-B27- restricted CTL response in Yersinia-induced reactive arthritis. J Immunol 1997, 159:5715–5723.

Mertz AK, Ugrinovic S, Lauster R, et al.: Characterization of the synovial T cell response to various recombinant Yersinia antigens in Yersinia enterocolitica-triggered reactive arthritis: heat-shock protein 60 drives a major immune response. Arthritis Rheum 1998, 41:315–326.

Mertz AK, Wu P, Sturniolo T, et al.: Multispecific CD4+ T cell response to a single 12-mer epitope of the immunodominant heat-shock protein 60 of Yersinia enterocolitica in Yersiniatriggered reactive arthritis: overlap with the B27-restricted CD8 epitope, functional properties, and epitope presentation by multiple DR alleles. J Immunol 2000, 164:1529–1537. This study gives a detailed report on single CD4+ T cell epitopes to the human heat shock protein 60 in one patient with Yersiniainduced ReA.

Granfors K, Jalkanen S, Lindberg AA, et al.: Salmonella lipopolysaccharide in synovial cells from patients with reactive arthritis. Lancet 1990, 335:685–688.

Kuon W, Sieper J: Identification of HLA-B27-restricted peptides in reactive arthritis and other spondyloarthropathies: computer algorithms and fluorescent activated cell sorting analysis as tools for hunting of HLA-B27-restricted chlamydial and autologous crossreactive peptides involved in reactive arthritis and ankylosing spondylitis. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 2003, 29:595–611.

Autenrieth IB, Beer M, Bohn E, et al.: Immune responses to Yersinia enterocolitica in susceptible BALB/c and resistant C57BL/6 mice: an essential role for gamma interferon. Infect Immun 1994, 62:2590–2599.

Yang X, HayGlass KT, Brunham RC: Genetically determined differences in IL-10 and IFN-gamma responses correlate with clearance of Chlamydia trachomatis mouse pneumonitis infection. J Immunol 1996, 156:4338–4344.

Simon AK, Seipelt E, Sieper J: Divergent T-cell cytokine patterns in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1994, 91:8562–8566.

Smeets TJ, Dolhain RJ, Breedveld FC, et al.: Analysis of the cellular infiltrates and expression of cytokines in synovial tissue from patients with rheumatoid arthritis and reactive arthritis. J Pathol 1998, 186:75–81.

Yin Z, Braun J, Neure L, et al.: Crucial role of interleukin-10/ interleukin-12 balance in the regulation of the type 2 T helper cytokine response in reactive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1997, 40:1788–1797.

Braun J, Yin Z, Spiller I, et al.: Low secretion of tumor necrosis factor alpha, but no other Th1 or Th2 cytokines, by peripheral blood mononuclear cells correlates with chronicity in reactive arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1999, 42:2039–2044.

Simon AK, Seipelt E, Wu P, et al.: Analysis of cytokine profiles in synovial T cell clones from chlamydial reactive arthritis patients: predominance of the Th1 subset. Clin Exp Immunol 1993, 94:122–126.

Kotake S, Schumacher HR, Jr., Arayssi TK, et al.: Gamma interferon and interleukin-10 gene expression in synovial tissues from patients with early stages of Chlamydia-associated arthritis and undifferentiated oligoarthritis and from healthy volunteers. Infect Immun 1999, 67:2682–2686. Interferon-gamma and IL-10 were found to be expressed in the synovial membrane of patients with Chlamydia-induced arthritis, pointing to a possible role of IL-10 in preventing an effective immune response.

Thiel A, Wu P, Lauster R, et al.: Analysis of the antigen-specific T cell response in reactive arthritis by flow cytometry. Arthritis Rheum 2000, 43:2834–2842. Using single cell analysis, Chlamydia- and Yersinia-derived proteins could be identified as T cell stimulatory, and the cytokine secretion pattern could be identified by flow cytometry technique.

Kaluza W, Leirisalo-Repo M, Marker-Hermann E, et al.: IL10.G microsatellites mark promoter haplotypes associated with protection against the development of reactive arthritis in Finnish patients. Arthritis Rheum 2001, 44:1209–1214. This genetic analysis suggests that IL-10 may play a role in protection against ReA. In this study, no correlation with IL-10 production was investigated, leaving it open whether a high or a low IL-10 production could be associated with ReA.

Leirisalo-Repo M: Prognosis, course of disease, and treatment of the spondyloarthropathies. Rheum Dis Clin North Am 1998, 24:737–751.

Purrmann J, Zeidler H, Bertrams J, et al.: HLA antigens in ankylosing spondylitis associated with Crohn’s disease: increased frequency of the HLA phenotype B27,B44. J Rheumatol 1988, 15:1658–1661.

Taurog JD, Richardson JA, Croft JT, et al.: The germ-free state prevents development of gut and joint inflammatory disease in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Exp Med 1994, 180:2359–2364.

Benjamin R, Parham P: Guilty by association: HLA-B27 and ankylosing spondylitis. Immunol Today 1990, 11:137.

Khan MA: HLA-B27 polymorphism and association with disease [editorial]. J Rheumatol 2000, 27:1110.

Zhou M, Sayad A, Simmons WA, et al.: The specificity of peptides bound to human histocompatibility leukocyte antigen (HLA)-B27 influences the prevalence of arthritis in HLA-B27 transgenic rats. J Exp Med 1998, 188:877–886.

Kuon W, Holzhütter HG, Appel A, et al.: Identification of HLAB27- restricted peptides from the Chlamydia trachomatis proteome with possible relevance to HLA-B27-associated diseases. J Immunol 2001, 167:4738. In this study, for the first time, the whole chlamydial proteome was screened for potentially pathogenic epitopes. Such an approach may help to identify causative peptides in patients with ReA and other spondyloarthropathies.

May E, Dulphy N, Frauendorf E, et al.: Conserved TCR beta chain usage in reactive arthritis; evidence for selection by a putative HLA-B27-associated autoantigen. Tissue Antigens 2002, 60:299–308. These data indicate that CD8+ T cells found in synovial fluid from different patients with ReA have seen the same yet unidentified antigen, suggesting that such an arthritogenic antigen may exist.

Colbert RA: HLA-B27 misfolding: a solution to the spondyloarthropathy conundrum? Mol Med Today 2000, 6:224.

Allen RL, O’Callaghan CA, McMichael AJ, Bowness P: Cutting edge: HLA-B27 can form a novel beta 2-microglobulin-free heavy chain homodimer structure. J Immunol 1999, 162:5045–5048. These data indicate that HLA-B27 can form homodimers on the cell surface, which may stimulate then not only CD8+ T cells but also CD4+ T cells.

Boyle LH, Goodall JC, Opat SS, Gaston JS: The recognition of HLA-B27 by human CD4(+) T lymphocytes. J Immunol 2001, 167:2619–2624.

Ramos M, Alvarez I, Sesma L, et al.: Molecular mimicry of an HLA-B27-derived ligand of arthritis-linked subtypes with chlamydial proteins. J Biol Chem 2002, 277:37573–37581.

Popov I, Dela Cruz CS: Breakdown of CTL tolerance to self HLA-B*2705 induced by exposure to Chlamydia trachomatis. J Immunol 2002, 169:4033–4038.

Bardin T, Enel C, Cornelis F, et al.: Antibiotic treatment of venereal disease and Reiter’s syndrome in a Greenland population. Arthritis Rheum 1992, 35:190–194.

Lauhio A, Leirisalo-Repo M, Lähdeuirta J, et al.: Double-blind, placebo-controlled study of three-month treatment with lymecycline in reactive arthritis, with special reference to Chlamydia arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1991, 34:6–14.

Sieper J, Fendler C, Laitko S, et al.: No benefit of long-term ciprofloxacin treatment in patients with reactive arthritis and undifferentiated oligoarthritis: a three month, multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled study. Arthritis Rheum 1999, 42:1386–1396.

Locht H, Kihlstrom E, Lindstrom FD: Reactive arthritis after salmonella among medical doctors: study of an outbreak. J Rheumatol 1993, 20:845–848.

Yli-Kerttula T, Luukkainen R, Yli-Kerttula U, et al.: Effect of a three month course of ciprofloxacin on the outcome of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2000, 59:565–570.

Yli-Kerttula T, Luukainen R, Moettoenen T, et al.: Effect of a three-month course of ciprofloxacin on the late prognosis of reactive arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2003, 62:880–884. Although these ReA patients did not show an improvement of their arthritis in the 1st year, after 3 months treatment with ciprofloxacin, they showed a benefit after 4 to 7 years compared with the placebo group. This benefit was especially evident in the HLA-B27-positive group.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Sieper, J. Disease mechanisms in reactive arthritis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 6, 110–116 (2004). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-004-0055-7

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11926-004-0055-7