Abstract

Background

Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, older adults have been prioritized in public health campaigns to limit social interactions and ‘cocoon’ in their homes. This limits the autonomy of older people and may have unintended adverse consequences.

Aims

To ascertain the self-reported physical and psychological effects of ‘cocooning’ and the expressed priorities of older adults themselves during the pandemic.

Methods

This is a cross-sectional, survey-based study involving 93 patients aged 65 and older, attending geriatric medicine out-patient and ambulatory day hospital services or our in-patient rehabilitation units. Demographic data was obtained from the medical records. Frailty level was calculated using the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), and disease burden was calculated with the Charlson Comorbidity Index.

Results

Mean age was 79.1 (range 66–96), 24% had dementia, and most were mildly frail (CFS < 5). One-third reported new feelings of depression, decreased mobility, and loss of enjoyment as a consequence ‘cocooning’. Loneliness was more prevalent amongst in-patients (38% vs 9%, p > 0.001). Respondents worried more about the risks of COVID-19 to their family than themselves. Expressed priorities varied from ‘enjoying life as much as possible’ to ‘protecting the development of children’.

Conclusions

Adverse consequences of ‘cocooning’ were commonly expressed amongst older adults. Public health policy should take into account the heterogeneity of this population and be sensitive to their self-expressed wishes and priorities.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

As the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded, it became clear that increasing age was an independent risk factor for mortality and long-term morbidity [1]. Other comorbidities prevalent amongst older adults such as chronic cardiac or respiratory conditions and frailty also confer increased risk of poor outcomes [1, 2]. In Ireland, 52% and 92% of all COVID-19-related hospitalizations and deaths, respectively, have occurred in the over 65 age group [3, 4]. The trend is similar internationally [5]. However, older adults are not a homogenous group and stereotyping as a vulnerable and fragile cohort could reinforce ageist perceptions, especially during the current pandemic, where older people might be seen as ‘the problem’.

A common public health response in many countries included advice that people over the age of 70 self-isolate, restrict movements outside the home, and curtail social interactions. Governments around the world have focused public health messaging to ‘target’ older adults to comply with these measures [6]. In Ireland, the term ‘cocooning’ was used in messaging, a term originally coined by Faith Popcorn in 1981 to signify ‘staying inside one’s home, insulated from perceived danger, instead of going out’. Undoubtedly, this advice was issued in an attempt to protect older adults from infection, prevent spread of disease amongst a potentially vulnerable population, and reduce the burden on the healthcare system. However, the input of the demographic most affected by these measures was not sought during their implementation. ‘Cocooning’ limits the autonomy of older adults, reducing opportunities to exercise and socialize and may have unanticipated consequences for those it aims to protect.

The aim of this study was to quantify the self-reported physical and behavioural-psychological effects of ‘cocooning’ in a cohort of older patients and to ascertain the expressed priorities of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods

Design, setting, and study population

This is a cross-sectional study utilizing a self-reported survey (Appendix). The study was conducted at a large urban teaching hospital and its associated off-site age-related rehabilitation unit in a catchment area of 450,000, 11% of whom are aged 65 or older. The hospital had high levels of COVID-19 associated admissions throughout the pandemic, with nearly 25% occupancy of the bed base at its peak.

A consecutive sample of adults > 65 years were invited to consent to a brief survey, between October and November 2020. This included inpatients in the rehabilitation unit and outpatients attending clinic or ambulatory day hospital. Respondents with a known diagnosis of dementia were included if they were able to provide informed consent and complete the questionnaire with or without assistance. Exclusion criteria were declining to participate or inability to consent and complete the survey due to severe cognitive impairment. Study was approved by the local research and ethics committee.

Data collection

Survey responses were collected on the day of clinic attendance or in the case of inpatients, during their hospital stay. An initial operational pilot demonstrated that respondents had a better understanding and completed questions better if either a staff member or relative guided them through the questionnaire. Thus, all surveys were completed with some non-directive assistance.

The survey consists of three sections. The first quantified self-reported physiological and psychological effects experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic; the second consisted of a five-point Likert scale quantifying the participant’s concern about contracting COVID-19; and the third examined the participant’s own expressed priorities during the pandemic. Demographic data including comorbidities were obtained from medical records. Frailty level was calculated using the Clinical Frailty Scale [7], and overall disease burden was calculated with the Charlson Comorbidity Index [8].

Statistical analysis

As patient’s situation was felt to be possibly relevant, responses were divided for analysis on basis of in-patient or out-patient status at the time of data collection. Continuous data was reported as means and standard deviation (SD) and categorical variables as proportions. Chi-squared test or Student’s t-test was used to evaluate the relationship between the two groups. Data was analysed using SAS statistical software.

Results

Demographics and comorbidities

Ninety-three participants completed the survey, 37 were in-patients in the rehabilitation unit, and 56 were out-patients. The mean age was 79.1 (range 66–96), and 45% were male. Table 1 summarizes patient demographics and comorbidities.

The most common comorbidities across both groups were hypertension (43%), dementia (24%), and diabetes (20%). In-patients surveyed had significantly higher rates of hypertension (p = 0.002) and obesity (p = 0.007), with a trend towards a higher rate of diabetes (0.07). There was a trend towards higher rates of dementia amongst out-patient participants (p = 0.06), reflecting the nature of ambulatory geriatric medicine services.

Overall, participants had moderate levels of comorbidity and frailty across both groups. The mean Charlson Comorbidity Index score was 5, indicating a 21% chance of 10-year survival. The mean Clinical Frailty Score was 4, indicating someone living with mild frailty who is vulnerable, while not dependent on others for help.

Physical and psychological effects

Table 2 summarizes the physical and psychological consequences reported due to the COVID-19 pandemic and ensuing social isolation restrictions. Fourteen percent reported avoiding seeking medical attention during the restrictions. The most commonly reported adverse effects included depression (35%), loss of enjoyment of life (34%), and decreased mobility (33%). In-patients reported significantly higher levels of reduced self-efficacy and loss of confidence in completing basic tasks of daily living (35% vs 16%, p = 0.03). They also suffered from increased loneliness as compared to the out-patient cohort (38% vs 9%, p > 0.001).

Priorities during the pandemic

Overall, 43% of older adults were ‘extremely worried’ about family while only 13% were ‘extremely worried’ about themselves contracting COVID-19. While half of respondents were ‘not worried’ or only ‘slightly worried’ about themselves, nevertheless they also believed contracting the disease would mean a > 50% mortality rate for them personally. Concern was not higher amongst in-patients, despite being in a potentially risky environment.

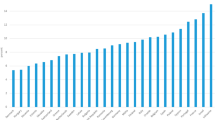

The highest ranking priority amongst all respondents was ‘keeping themselves safe’ from COVID-19 and ‘surviving the pandemic’ (29%). This was followed by prioritizing the ‘protection of other vulnerable groups’ and ‘ensuring the education and development of children’ (Fig. 1). In-patients tended to place more value on ‘enjoying their lives’ as much as possible despite the pandemic as compared to out-patients (35% vs. 12%, p = 0.007). Overall, priorities varied widely, with 50% of respondents placing the highest value on issues concerning people other than themselves.

Discussion

The COVID-19 pandemic has seen unprecedented volumes of published research as we try to better understand the nature and impact of this virus, including indirectly, on the population. Much of this research must rightly include older people living with frailty, cognitive impairment, and multi-morbidity [9]. A strength of this study is its focus on this particular cohort; nearly one-quarter of all respondents had a diagnosis of dementia, and most were at least mildly frail. This study is the first to describe older adult’s expressed priorities during the pandemic and supports the findings of Baily, et al. (2021) in describing the high prevalence of negative physical and psychological effects of ‘cocooning’ [10].

The negative impact of loneliness and social isolation amongst older adults on physical and psychological well-being has been previously described [11]. Loneliness is an independent risk factor for premature death, development of dementia, and depression [12]. This study reflects worrisome trends with one-third of older patients reporting worsening mobility, depression, and lack of enjoyment in their lives since the onset of the pandemic. Prior to ‘cocooning’ and other social distancing measures, over 70% of older adults living in Ireland reported rarely feeling lonely, with only 5% regularly feeling lonely [13]. Feelings of loneliness were reported in 20% of our patient cohort, especially among in-patients, likely reflecting hospital practices on restricted visits, use of isolation rooms, and staff personal protective equipment. However, even amongst community dwellers, feelings of loneliness nearly doubled from previously reported levels.

The desire to ‘enjoy one’s life as much as possible’ was a dominant theme expressed by older inpatients. Many had just experienced illnesses such as a stroke or hip fracture affecting independence. Their priorities may reflect the desire to return to pre-morbid levels of function, out-weighing any fear of COVID-19 infection. Interestingly, we noted most respondents felt, if infected, the virus would be most likely personally fatal, while expressing much higher levels of concern for younger family members than themselves. A wide range of personal priorities were expressed illustrating the heterogeneity of older adults. Many expressed ‘sustaining employment’ or ‘children’s education and development’ should be prioritized. Further strategies aimed at reducing mortality or pressure on health services may not have universal ‘buy-in’ if only emphasizing reduced mortality as an outcome among older people, especially if such measures also cause harm [14].

Protecting older adults has been emphasized in the effort to increase compliance with public health advice. Implementing social restrictions on all people over a certain age however is problematically ageist, classifying older adults as a homogenous risk, and undermining their autonomy [15]. Restrictions seem to commonly have negative effects on physical and psychological well-being of older patients. A more nuanced age-attuned approach to public health advice should also take into account older people’s priorities and attempt to support those most affected by social distancing measures.

Availability of data and material

Not applicable.

Code availability

Not applicable.

References

Imam Z, Odish F, O’Connor D et al (2020) Older age and comorbidity are independent mortality predictors in a large cohort of 1305 COVID-19 patients in Michigan, United States. J Intern Med 288:469–478

Zhou F, Yu T, Du R et al (2020) Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult in-patients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. The Lancet 395(10229):1054–1062

Central Statistics Office (2020) Accessed online:https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-covid19/covid-19informationhub/health/covid-19deathsandcasesstatistics/

Epidemiology of Covid-19 in Ireland (2020) Report prepared by HPSC on November 6, 2020. Accessed online: https://www.hpsc.ie/a-z/respiratory/coronavirus/novelcoronavirus/casesinireland/epidemiologyofcovid-19inireland/

Roser M, Ritchie H, Ortiz-Ospina E et al (2020) Statistics and research: coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19). Accessed online: https://ourworldindata.org/coronavirus

Utych SM, Fowler L (2020) Age-based messaging strategies for communication about COVID-19. J Behav Public Adm 3(1)

Rockwood K, Song X, MacKinght C et al (2005) A global clinical measure of fitness and frailty in elderly people. Can Med Assoc J 173:489–495

Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL et al (1987) A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. Journal of Chronic Disease 40(5):373–383

Richardson SJ, Carrol CB, Close J et al (2020) Research with older people in a world with COVID-19: identification of current and future priorities, challenges and opportunities. Age Ageing 49(6):901–906

Bailey L, Ward M, DiCosmio A et al (2021) Physical and mental health of older people while cocooning during the Covid-19 pandemic. QJM hcab015. https://doi.org/10.1093/qjmed/hcab015

Coyle CE, Dugan E (2012) Social isolation, loneliness and health among older adults. Journal of Ageing and Health 24(8):1346–1363

Donovan NJ, Blazer D (2020) Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: review and commentary of a national academies report. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry 28(12):1233–1244

Ward M, Layte R, Kenny RA (2019) Loneliness, social isolation, and their discordance among older adults: findings from The Irish Longitudinal Study on Ageing (TILDA). Trinity College Dublin. Accessed online: https://tilda.tcd.ie/publications/reports/pdf/Report_Loneliness.pdf

Daoust JF (2020) Elderly people and response to COVID-19 in 27 countries. PLoS ONE 15(7):e0235590. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235590

Vale MT, Stanley JT, Houston ML et al (2020) Ageism and behavior change during a health pandemic: a preregistered study. Front Psychol 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.587911

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

All authors have read and approved the manuscript. SM: study conception, data analysis and interpretation, drafting the manuscript. DF: data collection. RP: data collection. RC: study conception, revision of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Obtained from Tallaght University Hospital Research Ethics Committee, Tallaght University Hospital, Dublin, Ireland. All survey respondents gave verbal consent to participate in this study. Verbal explanation of the survey, the purpose of the study, and consent was considered appropriate by the ethics committee.

Consent for publication

All survey respondents were made aware and consented to the possibility of publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix survey

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Mello, S., Fitzhenry, D., Pierpoint, R. et al. Experiences and priorities of older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Ir J Med Sci 191, 2253–2256 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02804-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11845-021-02804-y