Abstract

Knowledge exchange is a broad and consequential undertaking, analysed by diverse scholars, and rapidly growing as a field of academic practice. Its remit is to strengthen ties between research generators and users to support better material outcomes for society. This review paper considers how this increasingly codified academic field might engage with the research-practice concerns identified in the Indigenous and decolonial literature. We do so by bringing the two literature sets together for analysis, noting they are not mutually exclusive. We reveal how addressing discrimination towards Indigenous peoples from within the knowledge exchange field requires a fundamental reconsideration of the biases that run through the field’s structures and processes. We prioritise two connected framing assumptions for shifting—jurisdictional and epistemological. The first shift requires a repositioning of Indigenous peoples as political–legal entities with societies, territories, laws and customs. The second shift requires engagement with Indigenous expert knowledge seriously on its own terms, including through greater understanding about expert knowledge creation with nature. These shifts require taking reflexivity much further than grasped possible or appropriate by most of the knowledge exchange literature. To assist, we offer heuristic devices, including illustrative examples, summary figures, and different questions from which to start the practice of knowledge exchange. Our focus is environmental research practice in western Anglophone settler-colonial and imperial contexts, with which we are most familiar, and where there is substantial knowledge exchange literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

In the words of my ancestors to say hello and what is your intention? I say Yaama.

B J Moggridge (BJM)

Many research and policy institutions in the western Anglosphere are shifting from why to how with respect to supporting and engaging with Indigenous peoples, as part of overturning discrimination and securing better material social and environmental outcomes for all (e.g. Hill et al. 2020; Reid et al. 2021). Practice is changing with Indigenous advisory boards and ethical codes becoming de rigueur (e.g. Woodward et al. 2020), while in Aotearoa New Zealand specific bio-cultural approaches are being crafted (e.g. Bargh et al. 2023). This shift is surfacing political–legal and epistemological complexities new to most non-Indigenous individuals and institutions working in research and policy, even though Indigenous leaders have raised them for generations (Rigney 1999; Watson 2017). Our interest here is with knowledge exchange scholarship, a field focused on improving the use and utility of expert knowledge beyond research contexts (Chambers et al. 2021; Cvitanovic et al. 2015; Reed et al. 2014; Turnhout et al. 2020). Champions of knowledge exchange often refer to the lack of translation of research into social, environmental and economic outcomes, and long-time lags between research and uptake, as motivating their work (Morris et al. 2011; Nguyen et al. 2016; Kinchin et al. 2017). We examine how this field can respond to the critiques of the Indigenous and decolonial literature, which also prioritises improving research–practice relationships (Gram-Hanssen et al. 2022; Hemming et al. 2010; Latulippe and Klenk 2020; Shibasaki et al. 2019; Watkin Lui et al. 2016). We write for non-Indigenous researchers and professionals who are motivated to bring their own practices and institutions into greater question, and potentially help generate decolonising spaces and practices.

We reveal how addressing discrimination towards Indigenous peoples from within the knowledge exchange field requires a fundamental reconsideration of the biases that run through the field’s structures and processes. The 2020 #BlackLivesMatter movement prompted some influential non-Indigenous institutions to turn towards this work, such as the journal Nature which acknowledged it had been ‘complicit in systemic racism’ (Nature Editorial 2020). Perhaps not anticipated is how this work demands more than addressing discrimination between people and institutions—it also requires addressing the discrimination generated in the conceptualisation of the world and our relationships with it. Our focus is with resetting: (1) assumptions; (2) relationships; and (3) institutions. These categories speak to both literature sets, but are chosen because of their currency with the knowledge exchange literature. Importantly, they are a platform for action. We cannot emphasise enough that building non-Indigenous capacity is insufficient. Conceptual learning needs to be accompanied with material change on terms meaningful to Indigenous peoples. Put differently, it is inadequate to acknowledge that Indigenous peoples and their expert knowledge are important; there must be material support for their jurisdictional presence and expert knowledge institutions.

We believe the potentially transformative space of knowledge exchange research-practice is well positioned to respond to the Indigenous/decolonial literature because of its imperative to improve knowledge exchange through strengthening relationships and trust, to achieve better material outcomes. In support, this paper offers pathways to move towards the research-practice alternatives in the Indigenous/decolonial literature. We offer heuristic devices, including illustrative examples, summary figures, and different starting questions. Our method brings the knowledge exchange and Indigenous/decolonial literature sets together for analysis and comparison, noting they are not mutually exclusive (e.g. Shibasaki et al. 2019; Watkin Lui et al. 2016).

The focus of this work is environmental research practice in western Anglophone settler-colonial and imperial contexts, with which we are most familiar, and where there is also substantial knowledge exchange literature that seeks to enable societal transformation to respond to global environmental crises (Fazey et al. 2014; Reyes-García et al. 2021; DePuy et al. 2022), including improved understandings of ‘human–nature’ relationships for sustainability (Norström et al. 2020). We draw on examples and experiences from Australia where we live and work on unceded Indigenous lands, known here as Country and also signified as Land. Our audience includes people involved in both developing policy- and practice-oriented research, and growing and transforming the scholarly and institutional spaces of knowledge exchange within universities, research user agencies, and public, private and community sector research institutions. Our starting point is that: all environmental research and knowledge exchange in settler-colonial contexts is undertaken on Indigenous lands; that imperial powers globally remain embedded materially, politically and culturally with colonial histories and geographies; and, that individuals and institutions benefiting from injustice have the responsibility to do something about it.

Positioning and approach

We, Jessica Weir, Rachel Morgain and Katie Moon (‘we’—throughout the paper), write from the contingent position of being non-Indigenous scholars, which is indicative of structural inequities where we work (de Leeuw and Hunt 2018). Our work is both constrained and charged by our positionality (McLean et al. 2019). Our colleague, Kamilaroi man and scientist Bradley Moggridge, inserts his scholarship and thoughts into the paper as ‘BJM’ to disrupt and augment the non-Indigenous text. Indigenous and non-Indigenous people may work in the same institutions and attend the same events, but different positionality means different experiences, responsibilities, priorities and insights.

Indigenous people are more often the researched rather than the researcher especially in the fields of water and natural resource management. Our knowledge and methodologies have become highly sought after for seeking solutions to the many hundreds of years of abject failings of colonial ways of devaluing and not caring for Country. I wish to change this paradigm by becoming that researcher in my area of scholarly research, validating traditional knowledge, and telling my stories my way. BJM

The idea for the paper emerged from a 3-day knowledge exchange workshop held at the Australian National University (2018) with approximately 30 researchers and practitioners. Rachel as co-organiser invited a panel on Indigenous/decolonial priorities, with Bradley and Jessica co-presenting, alongside Torres Strait Islander research colleagues. Katie was in the audience and connected with the panel. The Indigenous presenters declined to lead or co-author a paper responding to the Indigenous/decolonial concerns raised, but have supported this paper as an allied contribution, as considered important within the literature (e.g. Hird et al. 2023; Reyes-García et al. 2021; Obura et al. 2021). Given our contingent non-Indigenous position, we recommend readers prioritise reading and citing the Indigenous (including co-authored) literature. We also acknowledge that both the field of knowledge exchange and the Indigenous/decolonial literature are more nuanced than presented here.

We intend this paper to be a respectful considered engagement with Indigenous peoples’ scholarship, drawing out insights to build non-Indigenous capacity and action. Nonetheless, this paper will involve translations that may be transgressions we do not yet appreciate. We align with scholarship that works across Indigenous and non-Indigenous difference, and digs into difficulties to foster creative, generative practice (e.g. Cusicanqui 2012; Nakata et al. 2012). We write cognisant that non-Indigenous people need to take responsibility for the ongoing injustices of imperial–colonial privilege, as informed by Indigenous leadership; indeed, most decolonial work needs to be undertaken by non-Indigenous people.

This paper has taken time. It has developed dialogically through interpersonal and group discussion, and then drafting and re-drafting, drawing on mis/communication across our different research-practice backgrounds to decide on scope and content. Notably, discussions became clearer after Katie learnt about knowledge discrimination from the Indigenous/decolonial scholarship (especially Kimmerer 2013; then brought that to her practice (Moon and Pérez-Hämmerle 2022; Pérez-Hämmerle et al. 2024)). Whereas Jessica deepened her expertise in the non-Indigenous science-policy/practice literature (Weir 2023; Weir et al. 2022), Rachel as a knowledge exchange practitioner with post-doctoral research in Pasifika studies and subsequently co-developing a range of initiatives with Indigenous researcher–practitioners, contributed both professional insights and scholarly expertise (Conservation Futures 2021; Dielenberg et al. 2023; Morgain et al. 2021). Fundamentally, we debated how to impactfully connect an audience unfamiliar to foregrounding imperial and colonial violence. We initially took a less direct approach, now discarded after generous encouragement from an anonymous Indigenous peer reviewer.

Illustrating dominant assumptions in knowledge exchange practice

Before engaging with the scholarship, we begin with two hypothetical research-practice examples about environmental management centred on natural science expertise. These consider what might typically be an effective knowledge exchange and co-production process—that is, a process designed to be inclusive of marginalised research users and generators. They reveal the influence of two assumptions predominant in the western Anglosphere that are discriminatory towards Indigenous peoples and provide an early unsettling exercise for readers who, whether consciously or not, may hold the two discriminatory assumptions. The examples are heuristic tools to illustrate the importance of positionality—knowing who we are, where we stand socially, economically and culturally, and the consequences of that for our worldviews, opportunities, networks and animating assumptions (e.g. Gilbert 2019).

The assumptions we refer to are jurisdictional, concerning governing authorities with societies and territories; and epistemological, concerning the creation and valuing of expert knowledge. First, the jurisdictional assumption: asserting a singular nation-state sovereignty by not recognising Indigenous peoples’ political–legal status as a co-located jurisdiction, and instead collapsing Indigenous peoples within the nation or ‘the mainstream’ as a special interest group or stakeholder (McGregor 2017; Strelein and Tran 2013; Watson 2017). And second, the epistemological assumption: privileging natural science expertise about nature—a nature that is separate from society, and considered to be most accurately known by minimising subjectivity (culture, values and ethics). This assumption does not recognise Indigenous peoples’ expert knowledge about nature as an equivalence and instead positions it as local, cultural and/or traditional knowledge (Hird et al. 2023; Tynan 2021; Whyte 2018a). The bulk of this paper grapples with analysing and negating the presence of these two assumptions, especially through relationships and institutions. However, consider for a moment the consequences of how they manifest in the two examples that follow.

In the first example, a research team is asked to look at the effects of industry activities on the distribution of an endangered species on land managed for mixed biodiversity conservation and production purposes. The production purposes might be forestry, viticulture, agricultural crops and/or grazing, with species protection supported alongside. The researchers and knowledge exchange specialists work closely with government partners to develop the research questions and design and then work side by side in the landscape to co-produce the findings. In the second, researchers work with a local community concerned about an invasive weed in their local landscape—perhaps a weed that smothers rivers or crowds out native grasses. Together, they design research to assess how to manage the weed and potential effects on the ecosystem, and they report regularly to, and hear back from, a committee that includes representatives from government, local council, a non-government land care organisation, wildlife volunteers and the Indigenous people on whose land they research. In either example, the research methods might be adapted to include participatory methods, such that Indigenous people may be invited as important stakeholders, to work as research assistants and/or share their knowledge about the species.

Whether for conservation or production, both examples focus on observing a species classified as invasive/endangered, including its presence, absence and interactions with other species within their habitats, to establish the land management priorities for funding and implementation. In each case, the natural science assumption of neutrality—i.e. claiming somewhat value-free independent research expertise about a nature separate to society—means that consideration is not given to the human relationships implicated in the research, or indeed to the classification and centring of the species themselves (Goolmeer et al. 2022). By seeking to rule out subjectivity in research method, the expertise is not observing, investigating or analysing the values and politics that are present in (a) the evidence, (b) the conservation/production management decisions based on that evidence and (c) their interactions. Consequently, these values and politics go uninterrogated. Indeed, as an ostensibly neutral expertise set, they do not even require interrogation. Instead, values or politics are to be in/adequately negotiated by individuals and institutions involved in the knowledge exchange process, who must grapple with the ostensibly value-free evidence set.

Significantly, the natural sciences (as discussed in more detail later) have created an analytical space that does not require going through any formal human ethics process to consider how people might be affected by ecological research. By observing nature to generate falsifiable facts that can be tested by anyone anywhere, this expertise is ostensibly separate to society in both research focus and methodology. Thus, there is no need to go through an ethics review process to explain how the researchers considered, and then asked permission from, the Indigenous peoples whose Country/Land it is, which they are affecting, working on and making decisions about; nor, it follows, are questions being asked with Indigenous people about: what research is being funded; who is funded to do it; which research questions are being asked; which methods are valid; how markers of success are defined; how policy and practice implications will be decided; and so on. Further, there is no need to interrogate the assumptions that underscore the non-Indigenous legal, material, political and conceptual foundations of the context where people meet, learn and exchange knowledge; nor, what expert knowledge ‘is’. Indeed, there is no need to consider Indigenous peoples’ presence at all. Indigenous people may be consulted for access if they hold nation-state recognised land titles, or because Indigenous rangers or training programmes are undertaking the work or if the research party wishes to do so.

The two examples highlight how tacit assumptions exist in knowledge exchange that may be viewed as apolitical or benign, or not even perceived at all, but nonetheless can carry practices of exclusion and marginalisation.

Indigenous peoples’ culturally significant species are not determined important through settler legislation, i.e., in Australia, the federal Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act. Cultural species play an important role in Indigenous life from being a spiritual being connected to the Buruuugu (Dreaming), a totemic species to a food resource. Yet, they are not able to be seen as significant or as a matter of national environmental significance under current legislation. There is also a complete blindness to the existence of Country—our Land, Water and Sky. An example is that a species on my Country is rare but common in surrounding territories, yet my cultural species cannot be assessed as “threatened” due to neighbouring numbers, in turn I cannot access funding or scientific assessment for it. BJM

Indigenous leaders often decline invitations to participate in knowledge exchange because of the repetitive emotional labour of arguing for respectful terms (Smith et al. 2023). This refusal is itself an assertion of what is at stake: the overturning of ‘distorted relations’ between Indigenous peoples and nation-states that position Indigenous peoples as the problem for not fitting in (after McGregor 2017); and, extractive approaches to Indigenous expert knowledge for the purposes of others (Tynan 2021). The work required to shift these two discriminatory assumptions is significant, but so too is the discrimination, which is why we think it is important.

Scholarship, context and background

Since the late 1970s, scholars in science and technology studies have investigated the social dimensions of the creation and use of research expertise, work undertaken largely in non-Indigenous settings by non-Indigenous scholars (e.g. Rohracher 2015; Collins et al. 2020; Pielke 2007). This scholarship has important points of connection with Indigenous and decolonial studies, including reflexivity about expert knowledge, and Indigenous scholars have also made significant contributions (e.g. TallBear 2013). One specialisation is the relatively new field of knowledge exchange. This field focuses on strengthening connections between research generators and users in research-informed practice as part of societal transformation. Its current approaches include co-production (Norström et al. 2020), knowledge brokering (Michaels 2009), knowledge adoption (Andrews 2012), knowledge translation (Shibasaki et al. 2019) and research impact (Lavery et al. 2021). It is built on the practice-based traditions that have sought to improve the uptake of expert knowledge in society—extension (Taylor and Bhasme 2018), boundary spanning (Bednarek et al. 2018), participation and engagement (Reed 2008), and policy research (Druckman 2015).

This genealogy is very different to Indigenous studies, which emerged in the 1970s with a commitment to Indigenous lands and waters, sovereignty and Indigenous perspectives (Philip 2015; Tuck and Yang 2019). This work includes Indigenous research methodologies that analyse how expert knowledge is created, judged and used (Arsenault et al. 2018; Smith et al. 2016; Whyte 2018a). Decolonisation studies are informed by Indigenous studies and focus on how understandings of time and place are operationalised by imperial and colonial powers globally to claim the land, labour and resources of Indigenous peoples (and others) (Cusicanqui 2012; Tuck and Yang 2019). Decolonial scholarship seeks to uncover and overturn these discriminatory moves, including within the research-practices of settler-colonial nation-states, their imperial centres and associated academic institutions (Hemming et al. 2010; McLean et al. 2019; Smith et al. 2023).

Knowledge exchange scholars and practitioners have sought means to redress and counteract extractive and potentially harmful research practices, with ‘co-production’ a key example (Turnhout et al. 2020; Chambers et al. 2021; Norström et al. 2020). Co-production is deliberately designed to extend the ownership of research-practice to Indigenous, local and other marginalised participants (see Cross-Chapter Box 4 in Abram et al. 2019). In co-production exercises, people from research and practice engage together as equals in the co-design of practice-relevant research activities and maintain engagement and co-ownership through the course of the project through to, and past, completion (Meadow et al. 2015; van Kerkhoff and Lebel 2015; Wyborn 2015). The method is intended to reduce conflict by bringing more equality to the knowledge exchange process and has explicitly questioned default power dynamics in relationships to do with knowledge generation and use (Turnhout et al. 2020). Power imbalances, however, can remain deeply embedded, often implicitly, even in this co-production work: for example, through the institutions and individuals that set the questions and parameters of the co-production process (Pohl et al. 2010; Colvin et al. 2020; Latulippe and Klenk 2020).

Such emerging practices in knowledge exchange are developing a deeper appreciation of Indigenous peoples and their institutions; however, from our experiences, such efforts by knowledge exchange individuals and institutions are still largely working within predominant colonial and imperial institutions (e.g. DCCEEW 2021). For example, in the two environmental management illustrations above, the jurisdictional and epistemological framing assumptions fundamentally imbued in management plans determine what matters, why and to whom and on whose authority. By not addressing the framing assumptions, as Indigenous scholars Latulippe and Klenk (2020, p. 7) write, even co-production would not be advisory and facilitative, but would instead be instrumentalist (i.e. a pre-determined scope of what is possible) and constitutive (i.e. filling in these boundaries with its own content).

In response, and following the lead of Indigenous scholars, we have prioritised two shifts to address discrimination and improve knowledge exchange: first, to understand Indigenous peoples as Indigenous peoples, that is, with societies, territories, laws and customs; second, to engage with Indigenous expert knowledge seriously on its own terms, in part through reframing predominant understandings of natural science expertise and authority. These two shifts require taking reflexivity much further than grasped as possible or appropriate by most of this field’s literature. Nonetheless, we urge them as a priority. As illustrated above and documented in the literature, knowledge exchange institutions and individuals, often unknowingly, operate with and within systems of colonial, settler-colonial and imperial privilege, which can compound the exclusion, erasure and dismissal of Indigenous peoples (Ruwhiu et al. 2022), and, when not checked, become self-perpetuating (e.g. Duncan et al. 2018). Moreover, currently knowledge exchange scholars and practitioners are collaborating globally to codify and formalise the field, with core approaches becoming ‘mainstreamed’ within policy-setting institutions and academic disciplines (Norström et al. 2020, p. 183).

Exploring assumptions in knowledge exchange

The connected jurisdictional and epistemological assumptions to shift are not minor deviations across Indigenous and non-Indigenous difference, but profound framing devices that determine whose laws and expertise are legitimate and resourced.

The first assumption (jurisdictional) to shift is to recognise (and then do something about) the fact that Indigenous peoples are not stakeholders within nation-states but jurisdictional authorities co-located within and across nation-state boundaries as ‘nested sovereignties’ (Simpson 2014). The term ‘peoples’ signals political–legal status. Indigenous peoples contribute to knowledge exchange with nation-states in multiple forms, including through negotiating self-determination mechanisms, such as treaties, rights and constitutional recognition—e.g. the Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit sharing under the Convention for Biological Diversity (Robinson et al. 2021). Globally there are 370 million Indigenous people, holding management or tenure rights over some 25% of the world’s land surface and intersecting with some 40% of reserved lands and ‘ecologically intact landscapes’ (i.e. landscapes identified as important by ecologists) (Garnett et al. 2018). These co-located sovereignties are accepted realities that nation-states navigate, although not always explicitly stating this (Strelein and Tran 2013). Indigenous peoples’ jurisdictional authority will always be in tension with the international order organised around nation-states, but this does not mean that it does not exist. The critical move is to ‘make space’ rather than discipline Indigenous peoples to ‘fit-in’ (Strelein and Tran 2013). Indeed, special provision for Indigenous peoples was identified as a priority in the creation of this now familiar new world order (Rowse 2008). This provision includes the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (established 2000) and the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (adopted 2007). UNDRIP articulates the responsibilities of nation-states to protect Indigenous peoples’ rights.

Nonetheless, our experience is that most knowledge exchange settings are not in contexts where Indigenous peoples are recognised as having Indigenous rights, including communal land and water rights (and responsibilities) held as societies with territories, and self-determination rights to enjoy the laws and customs of these societies and territories. For example, Indigenous peoples are routinely described as Indigenous communities, which implies interconnected social groupings without jurisdictional authority and whose ‘access’ to ‘resources’ is contingent rather than rightful and inherent (e.g. Norström et al. 2020, p. 186; Chambers et al. 2021, p. 989). Indeed, knowledge exchange research-practice accepts and reinforces the framing presence of settler-colonial institutions (including governments) who are always ‘at the table’. The field typically describes how it brings people together from across ‘sectors’ and as ‘research, government, non-government and community actors’ to build institutional capacity as part of societal transformation (e.g. Chambers et al. 2021, p. 983). This common starting point erases Indigenous peoples’ sovereign presence—Indigenous people are not understood as governing institutions with laws, societies and territories. This erasure discriminates against Indigenous peoples’ self-determination—to enjoy and pass on their laws, customs, culture, language and so on. In doing so, the capacity of knowledge exchange institutions and individuals to engage with jurisdictional complexity is diminished (e.g. Weir and Duff 2017).

For example, Australia’s most recent bushfire Royal Commission categorised, and then analysed, Indigenous peoples’ communal land and water titles as private property granted by the Crown (Binskin et al. 2020, p. 370)—a nation-state imaginary whereby several hundred self-determining Indigenous Nations do not exist. These diverse communal titles include native title which is not a Crown grant, but sourced in Indigenous law and recognised by the common law—it pre-exists the Crown and is ongoing (Strelein et al. 2001). At the very least, the Royal Commission could have created a new framing category for graphical depiction and analysis—e.g. Indigenous peoples’ communal land titles. Then, bushfire agencies, policy makers, practitioners, researchers and all others could engage with their consequence.

We are tired of being the researched, the governed. Instead, seek an invitation for you to listen to our stories at the sacred fire that have stood the test of time (thousands of generations). Non-Indigenous people, the time to champion the power shift for Indigenous people from the researched to the researcher is now and through time will be beneficial for all and provide, through a culturally appropriate knowledge exchange, the solutions to fix the past 236 years of decline in the health of Country.

Is it time for an Indigenous led 236-year recovery plan for Country, waters and sky? We think so. BJM

The second assumption (epistemological) is to recognise (and then do something about) the fact that Indigenous peoples’ expert knowledge is an equivalent expert knowledge about the world. Often described as relational and connected, Indigenous expert knowledge is renowned for holding subjectivity with objectivity, and nature with society, together in observations, analysis, findings and practice (Bodkin-Andrews et al. 2016). Sometimes called Indigenous science, it relies on ‘long-term place-based multi-sensory observation to produce complex evidential and expert understandings of the natural world incorporating spiritual entities and explanations…’ (Harriden 2023, p. 201). It is not free floating for anyone to use, but inseparable to the knowledge holders and places where it arises (Harris and Wasilewski 2004; Reid et al. 2021) and where it has governance value for Indigenous peoples’ collective continuance (Whyte 2018a). More than knowledge governance, it is an ethics for living—a relational accountability or ethical inter-being relationality with the Land/Country (Vásquez-Fernández and Ahenakew 2020). In this differentiated relationality, law is knowledge and knowledge is law. This expertise, as with any expertise, has standards. It is generated through institutions, methodologies and societies, with practices of adjudication and qualification (Smith et al. 2016; Tynan 2021).

In comparison, the field of knowledge exchange has evolved out of the western academic specialisation to study nature and society as separate categories (e.g. the natural and social sciences), and, further, to hyper-separate—such that nature cannot be society and vice versa (Plumwood 2002). For example, a tree cannot have human attributes, such as the capacity for speech. Significantly, this is not just a way of seeing the world, but a way of creating expert evidence about it, and, further, is iterative. The systemic ontological–epistemological foundations and methodologies of the natural sciences minimise subjectivity (values, culture, perspectives, etc.) in pursuit of an objective nature/reality (Harriden 2023; Vásquez-Fernández and Ahenakew 2020). This approach generates falsifiable facts from observing what ‘is’, based on the assumption that reality is ‘out there’, separate from the observer Knorr-Cetina 2017/1984; Moon and Pérez-Hämmerle 2022). It is a powerful coupled way of defining and knowing nature. Consider, for example, the term ‘the environment’ and ‘ecosystems’—as things separate from ‘society’. These do not simply name reality, but are concepts that co-evolved with the creation of environmental studies within colonial/imperial academic institutions in the twentieth century (Robin 2018; Pascual et al. 2021).

Combined, the natural science ways of framing and knowing the fundamental being of ‘nature’ as a domain in itself, and methods for studying that domain, have become centred, valued and represented as universal knowledge about a universal nature (Weir 2023). Whilst this embrace of universality and objectivity may rest on reductionist or reflexive approaches, it remains as the authority about a separate nature. Unfortunately, the corollary is that Indigenous expert knowledge is represented as local knowledge and consequently afforded less status as true or objective (Parke and Hikuroa 2021; Whyte 2018a). Because, whether reductionist or reflexive, in securing this expert knowledge position about nature as (somewhat) neutral, (somewhat) independent and (somewhat) objective, Indigenous expert knowledge is not just different but incomprehensible: unreal. Natural scientists routinely acknowledge subjectivity in their practice (e.g. algorithm choices), but understandings of nature are not similarly interrogated. The consequences are serious. Cast as local, community, and/or, traditional knowledge, Indigenous knowledge cannot move across time and contexts (Whyte 2013).

To have my traditional knowledge gained through generational exchange listening to my stories through on-Country experiences and being present around the ceremonial fires, and for that knowledge to not be accepted as evidence or deemed fiction or myth as a non-referenced exchange by the academy is hard to accept. This further disenfranchises and excludes me as an Indigenous researcher. BJM

The singular sovereignty narrative and the universal nature/knowledge coupling present Indigenous peoples with a fraught choice: to fit in through accepting terms at odds with their jurisdiction/epistemology, which risks co-option and erasure and requires self-censorship; or, choose not to participate and be excluded. This choice is actually false, because there is another option. First, all parties meet on respectful terms through accommodating cultural diversity through mutual recognition, consent and Indigenous continuity: that is, agreement by both parties on a form of mutual recognition; the consent of the peoples in relation to decisions that affect them; and the continuity of peoples’ laws and customs with the newer political associations now co-located on their lands (Tully 2004 [1995], pp. 56–58; see also Weir 2009, pp. 67–68). Second, all parties accept that there is a plurality of situated expert knowledge about the world, rather than one authoritative knowledge set which all can fit with. The influence of these jurisdictional and epistemological framing assumptions is represented in Fig. 1.

How two dominant framing assumptions in knowledge exchange offer a false choice to Indigenous peoples and a third framing that can support navigating complexity together [see further Morgan (2005/2006), Reid et al.(2021), Simpson (2014), Harriden (2023), Watson (2017, 2018) Whyte (2018b); ‘false choice’ after Tully (2004 [1995]), see also Weir (2009, 2023)]

Significantly, the discriminatory moves that present false choices, jurisdictional and epistemological, are steeped in abhorrent theories of racial eugenics and hierarchical civilisations that represent/ed Indigenous people (and their expert knowledge) as savages and inferior and White people (and their expert knowledge) as civilised and superior (Nakata 2007). These logics establish Indigenous peoples as primitive and not modern, who cannot survive in contemporary times (Gilbert 2019). Indigenous peoples must give up their Indigeneity to join society, or otherwise live in ‘cultural museums’ (Cusicanqui 2012). They support the Doctrine of Discovery, which justifies/d the imperial seizure of Indigenous lands and resources globally (Miller et al. 2010). This abhorrent heritage continues to be perpetuated today in imperial–colonial research-practice (Miller et al. 2010; Nakata 2007; Watson 2018).

When the frames in any process are considered inappropriate by one of the parties, the process will stifle communication and generate crossed purposes and likely marginalise the less institutionally powerful (Fraser 2007). We think here of significant networks of policy, research, conservation and land management agencies that regularly mobilise their resources and influence to build knowledge exchange processes to progress shared priorities without regard for Indigenous sovereignty, and/or mistreat Indigenous knowledge and authority by subsuming them into their purposes and priorities (Hemming et al. 2010; Whyte 2018b).

Exploring relationships in knowledge exchange

Assumptions in knowledge exchange affect the potential of relationships, with relationships considered central in both literature sets examining the use and utility of expert knowledge, by individuals and institutions of all kinds.

The Indigenous/decolonial literature documents how the most important relationships are between people and Country, and then between people themselves (Graham 2008). Indeed, expert knowledge comes from the Land or Country—it is known through and with the world, and people are not the only knowledge holders (Tynan 2021). In comparison, in knowledge exchange the emphasis is on human dimensions, including attentiveness to relationships, psychology, trust, habits and power (e.g. Iftekhar and Pannell 2015; Cairney and Weible 2017; Evans et al. 2017; Lacey et al. 2018; Cvitanovic et al. 2019). The knowledge exchange literature documents how building relationships between researchers and research users can, ideally, foster a space where the knowledge of each party can be respectfully shared, integrated and built upon (hence ‘exchange’). Knowledge exchange can involve practices such as research briefings to decision-makers, or research users feeding knowledge needs into the research design process; however, much knowledge exchange occurs informally through interpersonal relationships and peer-to-peer networks (Fazey et al. 2014). Figure 2 sets out some knowledge exchange principles from the literature.

Problems arise for knowledge exchange when Indigenous peoples are expected to acquiesce to the hyper-separated nature/society frames. Knowledge exchange contexts presume only humans will attend, speak, have expert knowledge and so on, and Indigenous people are not taken seriously when they bring in ancestors, landscape forms and more (Reo et al. 2017; Diver 2017). This divide is also evident with approaches seeking to ‘integrate’ Indigenous knowledge as ‘traditional ecological knowledge’ within universal nature/knowledge framings, which requires scoping out the relational accountability that gives this knowledge its content and value (Reid et al. 2021). Problems also arise with the singular sovereignty frame. It is routine for Indigenous peoples to be added to lists of people within the nation-state requiring policy attention, alongside people who are listed for reasons of gender, socio-economic status, dis/ability and so on. This strips Indigenous peoples of their political–legal status as peoples, albeit notwithstanding the citizenship rights of Indigenous people within the nation-state (McGregor 2017). Similarly, in Australia’s environmental policy, Indigenous peoples are described as communities, custodians and/or land and sea managers, but not jurisdictional presences with self-determination rights (e.g. DCCEEW 2021). The language of Indigenous Nations is becoming more commonly used in response to this flawed approach.

The cycles of government, research gaps, policy needs, and leadership have constantly impacted Indigenous advancement—in the research sector, major projects and rights-based compensatory actions e.g., water rights. There is a constant lack of Indigenous objectives and aims in a project’s terms of reference and then, when questioned, it is not funded or out of scope or, more deflating, it becomes an afterthought. This is tiring.

I was lucky to lead a new Aboriginal water unit in the NSW Government from 2012–2017. It was consequently dissolved with a change in executive leadership, which used, as a scapegoat, the Aboriginal Cultural Awareness training to argue the unit was no longer needed (NSW Office of Water 2012). This is the norm when Aboriginal people and/or programs build up relationships, confidence and deliver on outputs within government—they are torn down. I have many more examples. I am tired of this, imagine how tired my Elders are? BJM

Fundamentally different framing assumptions about jurisdictional presence and epistemological authority, combined with power asymmetries, can render discriminatory the seemingly anodyne knowledge exchange principles in Fig. 2. This needs to be addressed in its own right, but also because these exclusions and marginalisations thwart the goals of knowledge exchange itself.

Exploring institutions in knowledge exchange

As we have been revealing, the institutions—i.e. the structures and processes that can coalesce power and capacity, as well as undermine them—are accessed, operationalised and populated by individuals with differentiated political power, assumptions and forms.

It is reasonably well known in academia that power and knowledge are intertwined, because power affects how different actors decide what knowledge is salient, credible and legitimate, and therefore what action ought to be taken as a result of that knowledge (e.g. Colvin et al. 2020). For example, knowledge exchange researchers have critiqued how authoritative jargon is used by researchers when engaged in policy contexts (Laing and Wallis 2016), and how standpoints that assume neutrality and rationality can be used to de-politicise knowledge exchange and resist changing the status quo power arrangements (Turnhout et al. 2020). This understanding, however, is different from accounting for institutionalised colonial–imperial power in the Indigenous/decolonial literature.

The Indigenous/decolonial literature has documented how, in the settler-colonial nations of the former British Empire, Indigenous peoples are in an inferior position in a political economy organised around historical and contemporary colonial–imperial privilege (Hemming et al. 2010; Whyte 2018b). This includes institutional design choices by settler-colonial nation-states to pursue a uniform singular political–legal order, thereby gradually removing their own capacity for engagement with co-located Indigenous peoples (Tully 2004 [1995], pp. 116–129). However, after World War Two racial discrimination became increasingly untenable. For example, in the 1970s Australian governments introduced programmes and mechanisms to support Indigenous peoples’ self-determination rights, although many of these were destroyed or reformed in the 1990s (Strelein and Tran 2013, pp. 25–26). Nonetheless, with racial discrimination legislation (1975), Indigenous peoples now have nation-state recognised titles and management rights to over half the continent, although regulatory systems have not adjusted (Weir and Duff 2017). Fundamentally, Indigenous peoples rarely have a sustainable income source for their responsibilities. There is yet to be a redistribution of Australia’s tax monies devoted to governance, land stewardship and research institutions, to sustainably include Indigenous peoples’ governance authorities, land and water management, and research institutions. This will involve comprehensive settlements with individual Indigenous Nations, with an agenda that includes compensation for lands degraded and resources stolen.

On a global scale, the coalitions and networks of scholarly institutions and professional societies are likewise founded on knowledge and resources accrued through imperialism, which also accept the coupled nature/knowledge universalism that perpetuates the positioning of Indigenous expert knowledge (and its institutions) as inferior and thus discretionary. These power asymmetries keep playing out in knowledge exchange settings. For example, in the 2018 workshop that seeded this article, differences emerged between those participants who assumed that it was reasonable and appropriate to formalise a network of knowledge exchange practitioners from the UK, Australia and Aotearoa New Zealand without substantial Indigenous-led and decolonial work, and those who believed that this was a necessary precursor to founding any new initiative. Traction for change in these knowledge exchange contexts is occurring, although more so in addressing epistemological discrimination, including through being more reflexive about natural science expertise about nature (Pascual et al. 2021), than addressing jurisdictional discrimination.

Indigenous peoples are research users and generators of consequence. Whilst there will always be matters that are irresolvable and in tension, decolonially intended work can lead to outcomes meaningful to Indigenous scholars and leaders. The point is not to seek elements of Indigenous leadership for inclusion in the status quo, but to invest in Indigenous leadership and institutions as well as taking reflexivity further to locate and dismantle imperial and colonial privilege.

Indigenous people are often required to fit into the research programs long after the research questions and methodologies are developed, and then sought after to assist the researcher to answer their questions. My experiences have led me to flip the paradigm to seek my peoples’ questions they wish to have answered through research. Removing the power imbalance in the research question, the co-production then has more chance to benefit the Indigenous people; this is a small step in the right direction, if achieved. The beginning of a broader shift to address power imbalances in research, such as moving to an Indigenous Research Methodology that is culturally appropriate, to leading as co-authors, co-presenting at conferences and leading to co-benefit. BJM

The field of knowledge exchange can either grapple with the universal nature/knowledge privilege and the il/legitimacy of Indigenous jurisdictions or continue to offer Indigenous people the false choice of fitting in or rejecting the mainstream. The stakes are high, but so are the possibilities; which is why deep reflexivity about positionality is so important.

I do not walk away from the fact that non-Indigenous researchers can be our champions and supporters to provide through their privilege an opportunity for us to lead and be that voice. The non-Indigenous champion must then facilitate the opportunity by stepping back. The most common practice is placing Indigenous people and their knowledge as advisory not as evidence to determine and inform a decision for research or projects. Constantly being advisory and not being the decision maker, leaves an experienced Traditional Owner deflated. The times you wish to walk away from projects due to power imbalance is very common. BJM

Resetting assumptions, relationships and institutions in knowledge exchange with the Indigenous/decolonial literature

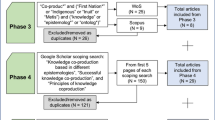

Indigenous leaders and scholars have always held standards about what is appropriate in knowledge exchange and have documented these as part of Indigenous studies. These standards reflect a history of extractive and abusive experiences, with recommendations that others should: ‘listen’; ‘seek out community protocols and follow them’; ‘be respectful and kind’; ‘provide value’; ‘demonstrate trustworthiness’; and ‘do no harm’ (e.g. Hemming et al. 2010; Watson and Huntington 2014; Jack et al. 2010; Watkin Lui et al. 2016; McLean et al. 2016; Ruwhiu et al. 2022; Hoffmann et al. 2012; Morishige et al. 2018; Arsenault et al. 2018). In responding to these recommendations, we have organised directives for working differently within the knowledge exchange space as: (1) resetting assumptions through respect, reciprocity, reflexivity and responsibility; (2) resetting relationships through The Long View, Setting the Table, design and application and deep listening; (3) resetting institutions through knowledge claims, knowledge sovereignty, resourcing and capacity, and positionality (Fig. 3).

Our interpretation of the key knowledge exchange standards identified in the Indigenous-led, co-authored and allied knowledge exchange literature (Barbour and Schlesinger 2012; Hemming et al. 2010; Hird et al. 2023; Hoffmann et al. 2012; Jack et al. 2010; Jos and Watson 2019; Latulippe and Klenk 2020; McGregor 2017; Maclean et al. 2022, 2021; Moggridge and Thompson 2021; Moggridge et al. 2019; Morgan (2005/2006); Morishige et al. 2018; Reid et al. 2021; Reo et al. 2017; Shibasaki et al. 2019; Watkin Lui et al. 2016; Watson 2017; Watson and Huntington 2014), to be considered in reference to the laws and protocols of each Indigenous Nation

Such standards are starting to be taken seriously by research institutions in Australia who develop their own guidelines with Indigenous leadership (e.g. DCCEEW 2021; Woodward et al. 2020). Consider, for example, Australia’s National Environmental Science Program. Following concerted work by Indigenous leaders and their allies within NESP Hubs in the first phase of the programme in 2015–2020, the second phase of the NESP instituted significant Indigenous governance structures and new guidelines requiring projects to engage with Indigenous peoples throughout the life of research projects, from conception to implementation, reporting and evaluation—an acknowledgement of Indigenous peoples’ land holdings and an amendment to colonial privilege (DCCEEW 2021). Significant parts of the programme now fund Indigenous-led research. Nonetheless, colonial privilege means that, with funds from the tax base, the Federal Environment Minister, through government department representatives, remains the final decider on the research programme, determining the scope (the environment) and who has the expertise (natural sciences).

My experiences in the Threatened Species Recovery Hub of the National Environmental Science Program as an Indigenous liaison officer were challenging initially as all the research questions and directions had been set. The evolution of the Hub to change its ways of researching was to include Indigenous people upfront and throughout the research and then to see the satisfying output of having Indigenous people co-present their research as co-authors leading to a respectful two-way exchange of knowledge, to ultimately benefit threatened species. I was employed to guide the Hub and researchers to follow protocols and principles and think outside the settler ways to engage Indigenous people respectfully. The production of the guidelines was crucial to support the shift in the Hub. BJM

In Fig. 3, we have sought to: centre the governance, decision-making, knowledge, reverence and modes of communicating of most importance to Indigenous peoples; and de-centre western and non-Indigenous governance, assumptions, priorities and ways of working that undermine Indigenous peoples’ self-determination. Nonetheless, we remind readers of our contingent non-Indigenous positionality. We share below what we have found important and insightful for each category. We affirm that we are each at different stages of understanding and meeting these standards, and that this involves making mistakes as part of ongoing learning.

Resetting assumptions by Respecting the Land we found is most instructive through Land-based learning, whereby Indigenous leaders can lead with multi-sensory approaches centred reverentially with Country (e.g. not assuming meetings happen inside meeting rooms). We emphasise that Reciprocity requires meeting priorities set by Indigenous peoples, whether perceived as fitting within the knowledge exchange activity or not. Embedding Reflexivity is intellectually challenging, and ‘two-eyed seeing’ (Reid et al. 2021) and techniques for shifting ontological supremacy (Hird et al. 2023: Fig. 1) are insightful starting points. Taking Responsibility needs to encompass policy settings, to ensure value for Indigenous peoples; and, if there is no value, it is critical to understand why not and then create new policies with accountability mechanisms.

Resetting relationships needs to take The Long View (a Māori strategic term) with the value of such partnership approaches evident in the bi-cultural regulatory work in Aotearoa New Zealand (e.g. Bargh et al. 2023), and in university–tribal partnerships (e.g. the UC Berkeley Collaborative with Karuk Tribe (Smith et al. 2023)). Our experience is that ‘Setting the Table’ is immensely valuable and instructive for all present, including protocols of meal sharing and storytelling (Watkin Lui et al. 2016). We have found centring Indigenous-led Design and implementation is only possible through established long-term collaborative relationships. Deep listening involves learning about Indigenous peoples’ histories to be ready to listen well, and, when listening, not being disrespectful by flaunting one’s own knowledge.

Resetting institutions by taking seriously Indigenous peoples’ Knowledge claims and Indigenous knowledge, is rarely understood as requiring a serious interrogation of one’s own expert knowledge. Respecting Knowledge sovereignty is possible through engaging specialist expertise to navigate the complexities of non-Indigenous law and regulation. We have found power asymmetries in Resourcing and capacity building are immediately apparent in who is funded to attend knowledge exchange activities, and, further, who is funded to build and share their knowledge as an occupation—i.e. Indigenous leaders often have a day job to pay the bills, whilst being researchers or policy makers is the day job for non-Indigenous participants. Finally, we return to Positionality—the importance of being candid and humble about the colonial–imperial privileges of one’s position and institutional setting.

Indigenous people have little choice but to do the reflexive and material work to navigate colonial and imperial privilege, whilst non-Indigenous institutions and individuals face little incentive to do so (Reid et al. 2021, p. 256). When seeking to work with Indigenous peoples, non-Indigenous individuals should attain ‘a basic level of education and sensitivity about one another’s cultural traditions, histories, values, priorities and aspirations’ (Reo et al. 2017, p. 64). Such conceptual learning must be accompanied with material outcomes, including the return of Land where Indigenous peoples’ coupled jurisdictional and epistemological authority is embedded. We recognise this is unexpected work for most, and yet it needs to be done if those of us benefiting from injustice wish to do something about it. This includes in institutions in imperial centres, which were built or developed through, and remain complicit in, colonial conquests and ‘settlement’.

Pathways for resetting assumptions, relationships and institutions in knowledge exchange

Because discrimination runs through the institutions, institutional structures and processes need to change. To work differently, knowledge exchange research-practice, both individually and institutionally, needs to: understand the extent to which it perpetuates discriminatory assumptions; recognise the protections afforded to ‘mainstream’ knowledge exchange by colonial–imperial privilege; and, then, seek to change the terms on which these dynamics play out. This work can be experienced as a threat or competition to the status quo. However, it is also an opportunity for learning for individuals and institutions. We reiterate, for the majority of non-Indigenous knowledge exchange scholars and professionals, examining the colonial and imperial privileges and assumptions of one’s own institutions, norms and practices, and learning to work differently, requires setting aside one’s own status as ‘expert’ to learn anew (Moon and Pérez-Hämmerle 2022).

Here, we offer questions to prompt interventions into knowledge exchange research-practice to take reflexivity and material action further. We follow Anishinaabe scholar Deborah McGregor who identifies that colonial nation-states, scholars and societies need to be asking different questions (2017). Figure 4 sets out some such questions to assist action from a different starting point, as organised by the three categories: assumptions, relationships and institutions (Fig. 4). Again, what we offer here are heuristic tools with the caveats about non-Indigenous positionality noted above.

Three interrelated dimensions of knowledge exchange for investigation and remediation (for related work, see Table 1 about scientific expertise in Hird et al. 2023)

These questions reveal how achieving more respectful terms is not an incremental adjustment to knowledge exchange, but an unsettling and overturning of many colonial–imperial privileges that underpin routine practices of knowledge exchange. In addition to really respecting very different onto-epistemologies, worldviews and life experiences and practices, it involves materially addressing who has institutional authority and resources. There is significant Indigenous, co-authored and decolonial allied scholarship to learn from. Its presence, however, is often neglected, or is briefly acknowledged without taking the critiques on board. We see this in the synthesis papers about knowledge exchange that wish to be respectful, but do not see the paradigm shift required.

Here I challenge the researcher, practitioner and reader as well as the academy, government and others, to flip the research paradigm and power dynamic and start afresh. Build a culturally sound relationship with Indigenous people through a respectful amount of time (not government funding or research funding timeframes), in that time trust will be established to free the barriers of the past. The challenge then extends to the researcher becoming the researched and seeking the questions Indigenous people have about their Country, waters, skies, and species. This shift in research will benefit all in the knowledge exchange. BJM

Conclusion

Respect for Indigenous peoples’ presence, knowledge and authority requires labour, but so too does the work of excusing or evading the epistemological and jurisdictional injustices of imperial–colonial privilege (e.g. Jurskis and Underwood 2013; Fletcher et al. 2021). We have prioritised intervening in knowledge exchange literature because this work is so important, and the field’s pursuit of improving the exchange of knowledge allows traction for change. As scholarship and practice grows, Indigenous scholars and leaders are again asking non-Indigenous people, who continue to benefit from colonial and imperial privilege, to acknowledge the discrimination in current arrangements and address it by aligning with principles of non-discrimination. Such work goes well beyond individual research projects and the actions of knowledge exchange practitioners, but all need to be involved. Those of us who are leading the actions and processes of knowledge exchange and their theoretical articulation can choose whether to concede to discriminatory systems or speak back to them.

References

Abram N, Gattuso J-P, Prakash A, Cheng L, Chidichimo MP, Crate S, Enomoto H, Garschagen M, Gruber N, Harper S, Holland E, Kudela RM, Rice J, Steffen K, von Schuckmann K (2019) Framing and context of the report. In: Pörtner LH-O, Roberts DC, Masson-Delmotte V, Zhai P, Tignor M, Poloczanska E, Mintenbeck K, Alegría A, Nicolai M, Okem A, Petzold J, Rama B, Weyer NM (eds) IPCC Special Report on the Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Geneva

Andrews K (2012) Knowledge for purpose: managing research for uptake—a guide to a knowledge and adoption program. Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities, Canberra

Arsenault R, Diver S, McGregor D, Witham A, Bourassa C (2018) Shifting the framework of Canadian water governance through indigenous research methods: acknowledging the past with an eye on the future. Water 10(1):49

Barbour W, Schlesinger C (2012) Who’s the boss? Post-colonialism, ecological research and conservation management on Australian indigenous lands. Ecol Manage Restor 131:36–41

Bargh M, Jones C, Carr EM, O’Connor C, Gillies T, McMillan O, Tapsell E (2023) Me Tū ā-Uru: for a flourishing and abundant environment report. New Zealand’s Biological Heritage National Science Challenge | Ngā Koiora Tuku Iho. Adaptive Governance and Policy Working Group

Bednarek AT, Wyborn C, Cvitanovic C, Meyer R, Colvin RM, Addison PFE, Close SL, Curran K, Farooque M, Goldman E, Hart D, Mannix H, McGreavy B, Parris A, Posner S, Robinson C, Ryan M, Leith P (2018) Boundary spanning at the science–policy interface: the practitioners’ perspectives. Sustain Sci 13(4):1175–1183

Binskin M, Bennett A, Macintosh A (2020) Royal commission into national natural disaster arrangements report. Commonwealth of Australia, Australia

Bodkin-Andrews G, Bodkin AF, Andrews UG, Whittaker A (2016) Mudjil’Dya’Djurali Dabuwa’Wurrata (How the White Waratah Became Red): D’harawal storytelling and welcome to country “controversies.” Alternat Int J Indig Peoples 12(5):480–497

Cairney P, Weible CM (2017) The new policy sciences: combining the cognitive science of choice, multiple theories of context, and basic and applied analysis. Policy Sci 50(4):619–627

Chambers JM, Wyborn C, Ryan ME et al (2021) Six modes of co-production for sustainability. Nat Sustain 4:983–996

Collins H, Evans R, Durant D, Weinel M (2020) Experts and the will of the people: society, populism and science. Palgrave, Switzerland

Colvin RM, Witt GB, Lacey J (2020) Power, perspective, and privilege: the challenge of translating stakeholder theory from business management to environmental and natural resource management. J Environ Manage 271:1–9

Conservation Futures (2021) Integrated knowledge system. Conservation Futures https://www.conservationfutures.org.au. Accessed 6 Dec 2023

Cusicanqui SR (2012) Ch’ixinakax utxiwa: a reflection on the practices and discourses of decolonization. South Atl Q 111(1):95–109

Cvitanovic C, Hobday AJ, van Kerkhoff L, Wilson SK, Dobbs K, Marshall NA (2015) Improving knowledge exchange among scientists and decision-makers to facilitate the adaptive governance of marine resources: a review of knowledge and research needs. Ocean Coast Manage 112:25–35

Cvitanovic C, McDonald J, Hobday AJ (2016) From science to action: principles for undertaking environmental research that enables knowledge exchange and evidence-based decision-making. J Environ Manage 183:864–874

Cvitanovic C, Howden M, Colvin RM, Norström A, Meadow AM, Addison PFE (2019) Maximising the benefits of participatory climate adaptation research by understanding and managing the associated challenges and risks. Environ Sci Policy 94:20–31

DCCEEW (Department of Climate Change, Energy, the Environment and Water) (2021) NESP indigenous partnership principles. National Environmental Science Program, Canberra

De Leeuw S, Hunt S (2018) Unsettling decolonizing geographies. Geogr Compass 12:1–14

DePuy W, Weger J, Foster K, Bonanno AM, Kumar S, Lear K, Basilio R, German L (2022) Environmental governance: Broadening ontological spaces for a more livable world. Environ Plan E Nat Space 5(2):947–975

Dielenberg J, Bekessy S, Cumming GS, Dean AJ, Fitzsimons JA, Garnett S, Goolmeer T et al (2023) Australia’s biodiversity crisis and the need for the biodiversity council. Ecol Manage Restor 24(2–3):69–74

Diver S (2017) Negotiating Indigenous knowledge at the science-policy interface: insights from the Xáxli’p community forest. Environ Sci Policy 73:1–11

Druckman JN (2015) Communicating Policy-Relevant Science. PS Polit Sci Polit 48(S1):58–69

Duncan T, Villarreal-rosas J, Carwardine J, Garnett ST, Robinson CJ (2018) Influence of environmental governance regimes on the capacity of indigenous peoples to participate in conservation management. PARKS Int J Protect Areas Conserv 24(2):87–102

Editorial N (2020) Systemic racism: science must listen, learn, and change. Nature 582:147

Evans MC, Davila F, Toomey A, Wyborn C (2017) Embrace complexity to improve conservation decision making. Nat Ecol Evol 1(11):1588

Fazey I, Bunse L, Msika J, Pinke M, Preedy K, Evely AC, Lambert E, Hastings E, Morris S, Reed MS (2014) Evaluating knowledge exchange in interdisciplinary and multi-stakeholder research. Glob Environ Chang 25:204–220

Fletcher MS, Romano A, Connor S, Mariani M, Maezumi SY (2021) Catastrophic bushfires, indigenous fire knowledge and reframing science in Southeast Australia. Fire 4(3):61

Fraser N (2007) Reframing justice in a globalising world. In: Connolly J, Leach M, Walsh L (eds) Recognition in politics: theory, policy and practice. Cambridge Scholars Press, UK, pp 16–35

Garnett ST, Burgess ND, Fa JE et al (2018) A spatial overview of the global importance of indigenous lands for conservation. Nat Sustain 1:369–374

Gilbert S (2019) Living with the past: the creation of the stolen generation positionality. Alternat Int J Indig Peoples 15(3):226–233

Goolmeer T, Skroblin A, Grant C, van Leeuwen S, Archer R, Gore-Birch C, Wintle BA (2022) Recognizing culturally significant species and Indigenous-led management is key to meeting international biodiversity obligations. Conserv Lett 15:e12899

Graham M (2008) Some thoughts on the philosophical underpinnings of aboriginal worldviews. Aust Human Rev 45:181–194

Gram-Hanssen I, Schafenacker N, Bentz J (2022) Decolonizing transformations through ‘right relations.’ Sustain Sci 17:673–685

Harriden K (2023) Working with Indigenous science(s) frameworks and methods: challenging the ontological hegemony of ‘western’ science and the axiological biases of its practitioners. Methodol Innov 16(2):201–214

Harris LD, Wasilewski J (2004) Indigeneity, an alternative worldview: four R’s (relationship, responsibility, reciprocity, redistribution) vs. two P’s (power and profit). Sharing the journey towards conscious evolution. Syst Res Behav Sci 21:489–503

Hemming S, Rigney D, Berg S (2010) Researching on Ngarrindjeri Ruwe/Ruwar: methodologies for positive transformation. Aust Aborig Stud 2:92–106

Hill R et al (2020) Knowledge co-production for Indigenous adaptation pathways: transform post-colonial articulation complexes to empower local decision-making. Glob Environ Change 65:102161

Hird C, David-Chavez D, Gion S, van Uitregt V (2023) Moving beyond ontological (worldview) supremacy: indigenous insights and a recovery guide for settler-colonial scientist. J Exp Biol 226:jeb245302

Hoffmann BD, Roeger S, Wise P, Dermer J, Yunupingu B, Lacey D, Yunupingu D, Marika B, Marika M, Panton B (2012) Achieving highly successful multiple agency collaborations in a cross-cultural environment: experiences and lessons from Dhimurru Aboriginal Corporation and partners. Ecol Manage Restor 131:42–50

Iftekhar MS, Pannell DJ (2015) “Biases” in adaptive natural resource management. Conserv Lett 8(6):388–396

Jack SM, Brooks S, Furgal CM, Dobbins M (2010) Knowledge transfer and exchange processes for environmental health issues in Canadian Aboriginal communities. Int J Environ Res Public Health 7(2):651–674

Jos PH, Watson A (2019) Privileging knowledge claims in collaborative regulatory management: an ethnography of marginalization. Admin Soc 51(3):371–403

Jurskis V, Underwood R (2013) Human fires and wildfires on Sydney sandstones: history informs management. Fire Ecology 9(3):8–24

Kimmerer RW (2013) Braiding sweetgrass: indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants. Milkweed editions, Minneapolis

Kinchin I, Mccalman J, Bainbridge R, Tsey K, Watkin Lui F (2017) Does indigenous health research have impact? A systematic review of reviews. Int J Equity Health 16(1):52

Knorr-Cetina KK (2017/1984) The fabrication of facts: toward a microsociology of scientific knowledge. In: Stehr N, Meja V (eds) Society and knowledge. Routledge, New York

Lacey J, Howden M, Cvitanovic C, Colvin RM (2018) Understanding and managing trust at the climate science–policy interface. Nat Clim Chang 1:22–28

Laing M, Wallis PJ (2016) Scientists versus policy-makers: building capacity for productive interactions across boundaries in the urban water sector. Environ Sci Policy 66:23–30

Latulippe N, Klenk N (2020) Making room and moving over: knowledge co-production, Indigenous knowledge sovereignty and the politics of global environmental change decision-making. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 42:7–14

Lavery TH, Morgain R, Fitzsimons JA, Fluin J, Macgregor NA, Robinson NM, Scheele BC et al (2021) Impact indicators for biodiversity conservation research: measuring influence within and beyond academia. Bioscience 71(4):383–395

Maclean K, Woodward E, Jarvis D et al (2021) Decolonising knowledge co-production: examining the role of positionality and partnerships to support Indigenous-led bush product enterprises in northern Australia. Sustain Sci 17:333–350

Maclean K, Greenaway A, Grünbühel C (2022) Developing methods of knowledge co-production across varying contexts to shape sustainability science theory and practice. Sustain Sci 17:325–332

McGregor D (2017) From ‘decolonized’ to reconciliation research in Canada: drawing from indigenous research paradigms. ACME Int J Crit Geogr 17(3):810–831

McLean J, Howitt R, Colyer C, Raven M, Woodward E (2016) Giving back: report on the ‘collaborative research in indigenous geographies’ workshop. AIATSIS, Canberra, 30 June 2015. Aust Aborig Stud 2:121–126

McLean J, Graham M, Suchet-Pearson S, Simon H, Salt J, Parashar A (2019) Decolonising strategies and neoliberal dilemmas in a tertiary institution: nurturing care-full approaches in a blended learning environment. Geoforum 101:122–131

Meadow AM, Ferguson DB, Guido Z, Horangic A, Owen G, Wall T (2015) Moving toward the deliberate coproduction of climate science knowledge. Weather Clim Soc 7:179–191

Michaels S (2009) Matching knowledge brokering strategies to environmental policy problems and settings. Environ Sci Policy 12(7):994–1011

Miller RJ, Ruru J, Behrendt L, Lindberg T (2010) Discovering indigenous lands the doctrine of discovery in the English colonies. Oxford UP, Oxford

Moggridge BJ, Thompson RM (2021) Cultural value of water and western water management: an Australian Indigenous perspective. Austral J Water Resour 25(1):4–14

Moggridge BJ, Betterridge L, Thompson RM (2019) Integrating aboriginal cultural values into water planning: a case study from New South Wales, Australia. Austral J Environ Manage 26(3):273–286

Moon K, Pérez-Hämmerle K-V (2022) An accountability framework for inclusive policy-making. Conserv Lett 15(5):1–10

Morgain R, Bekessy S, Bush J, Butler D, Cadenhead N, Clarke R, Croeser T et al (2021) Nature as a climate solution: country, culture and nature-based solutions for mitigating climate change. Report. University of Melbourne, October 2021

Morgan M (2005/2006) Colonising religion. Chain Reaction. Summer:36–37

Morishige K et al (2018) Nā Kilo ʻĀina: visions of biocultural restoration through indigenous relationships between people and place. Sustainability 10:3368

Morris ZS, Wooding S, Grant J (2011) The answer is 17 years, what is the question: understanding time lags in translational research. J R Soc Med 104(12):510–520

Nakata M (2007) Discipling the savages, savaging the disciplines. Aboriginal Studies Press, Canberra, ACT

Nakata M, Nakata V, Keech S, Bolt R (2012) Decolonial goals and pedagogies for indigenous studies. Decolonization Indig Educ Soc 1(1):120–140

Nguyen VM, Young N, Cooke SJ (2016) A roadmap for knowledge exchange and mobilization research in conservation and natural resource management. Conserv Biol 31(4):789–798

Norström AV, Cvitanovic C, Löf MF et al (2020) Principles for knowledge co-production in sustainability research. Nat Sustain 3:182–190

NSW Office of Water (2012) Our water our country: an information manual for aboriginal people and communities about the water reform process, 2nd edn. NSW Department of Primary Industries, Office of Water, Sydney, NSW

Obura DO, Katerere Y, Mayet M et al (2021) Integrate biodiversity targets from local to global levels. Science 373:746–748

Parke E, Hikuroa DCH (2021) Let’s choose our words more carefully when discussing mātauranga Māori and science. The Conversation 4 August 2021, Melbourne. https://theconversation.com/lets-choose-our-words-more-carefully-when-discussing-matauranga-maori-and-science-165465

Pascual U, Adams WM, Díaz S et al (2021) Biodiversity and the challenge of pluralism. Nat Sustain 4:567–572

Pérez-Hämmerle K-V, Moon K, Possingham HP (2024) Unearthing assumptions and power: a framework for research, policy, and practice. One Earth. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.oneear.2024.01.003

Philip KS (2015) Indigenous knowledge: science and technology studies. In: Wright JD (ed) International encyclopedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Pielke RA (2007) The honest broker making sense of science in policy and politics. Cambridge UP, Cambridge

Plumwood V (2002) Decolonising relationships with nature. PAN Philos Activism Nat 2:7–30

Pohl C, Rist S, Zimmermann A, Fry P, Gurung GS, Schneider F, Speranza CI, Kiteme B, Boillat S, Serrano E, Hadorn GH, Wiesmann U (2010) Researchers’ roles in knowledge co-production: experience from sustainability research in Kenya, Switzerland, Bolivia and Nepal. Sci Public Policy 37:267–281

Reed M (2008) Stakeholder participation for environmental management: a literature review. Biol Conserv 141:2417–2431

Reed MS, Stringer LC, Fazey I, Evely AC, Kruijsen JHJ (2014) Five principles for the practice of knowledge exchange in environmental management. J Environ Manage 146:337–345

Reid AJ, Eckert LE, Lane JF, Young N, Hinch SG, Darimont CT, Cooke SJ, Ban NC, Marshall A (2021) “Two-eyed seeing”: an indigenous framework to transform fisheries research and management. Fish Fish 22:243–261

Reo NJ, Whyte KP, McGregor D, Smith MA, Jenkins JF (2017) Factors that support indigenous involvement in multi-actor environmental stewardship. Alternat Int J Indig Peoples 13(2):58–68

Reyes-García V, Fernández-Llamazares Á, Aumeeruddy-Thomas Y et al (2021) Recognizing indigenous peoples’ and local communities’ rights and agency in the post-2020 biodiversity agenda. Ambio 51(1):84–92

Rigney LI (1999) Internationalization of an Indigenous anticolonial cultural critique of research methodologies: a guide to indigenist research methodology and its principles. Wicazo Sa Rev 14(2):109–121

Robin L (2018) Environmental humanities and climate change: understanding humans geologically and other life forms ethically. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Clim Change 9(1):1–18

Robinson D, Raven M, Makin E, Kalfatak D, Hickey F, Tari T (2021) Legal geographies of kava, kastom and indigenous knowledge: next steps under the Nagoya protocol. Geoforum 118:169–179

Rohracher H (2015) History of science and technology studies. In: Wright JD (ed) International encyclopaedia of the social & behavioral sciences, 2nd edn. Elsevier, Amsterdam

Rowse T (2008) Indigenous culture: the politics of vulnerability and survival. In: Bennett T, Frow J (eds) The SAGE handbook of cultural analysis. SAGE Publications, London, pp 406–426

Ruwhiu D, Arahanga-Doyle H, Donaldson-Gush R et al (2022) Enhancing the sustainability science agenda through Indigenous methodology. Sustain Sci 17:403–414

Shibasaki S, Sibthorpe B, Watkin Lui F, Harvey A, Grainger D, Hunter C, Tsey K (2019) Flipping the researcher knowledge translation perspective on knowledge use: a scoping study. Alternat Int J Indig Peoples 15(3):271–280

Simpson A (2014) Mohawk interruptus: political life across the borders of settler states. Duke University Press, Duke

Smith LT, Maxwell TK, Puke H, Temara P (2016) Indigenous knowledge, methodology and mayhem: what is the role of methodology in producing indigenous insights? A discussion from Matauranga Maori. Knowl Cult 4(3):131

Smith C, Diver S, Reed R (2023) Advancing indigenous futures with two-eyed seeing: strategies for restoration and repair through collaborative research. Environ Plan F 2(1–2):121–143

Strelein L, Tran T (2013) Building indigenous governance from native title: moving away from ‘fitting-in’ to creating a decolonized space. Rev Constitution Stud/rev D’étud Constitution 18(1):19–47

Strelein L, Dodson M, Weir JK (2001) Understanding non-discrimination: native title law and policy in a human rights context. Balayi Cult Law Colonial 3:113–148

TallBear K (2013) Native American DNA: tribal belonging and the false promise of genetic science. University of Minnesota Press, USA, pp 1–256

Taylor M, Bhasme S (2018) Model farmers, extension networks and the politics of agricultural knowledge transfer. J Rural Stud 64:1–10

Tuck E, Yang KW (2019) Series editors’ introduction. In: Smith LT, Tuck E, Yang KW (eds) Indigenous and decolonizing studies in education: mapping the long view. Routledge, Milton Park

Tully J (1995) Strange multiplicity: constitutionalism in an age of diversity. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge

Turnhout E, Metze T, Wyborn C, Klenk N, Louder E (2020) The politics of co-production: participation, power, and transformation. Curr Opin Environ Sustain 42:15–21

Tynan L (2021) What is relationality? Indigenous knowledges, practices and responsibilities with kin. Cult Geogr 28(4):597–610

Van Kerkhoff LE, Lebel L (2015) Coproductive capacities: rethinking science-governance relations in a diverse world’. Ecol Soc. https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-07188-200114

Vásquez-Fernández AM, Ahenakew C (2020) Resurgence of relationality: reflections on decolonizing and indigenizing ‘sustainable development.’ Curr Opin Environ Sustain 43:65–70

Watkin Lui F, Kiatkoski Kim M, Delisle A, Stoeckl N, Marsh H (2016) Setting the table: indigenous engagement on environmental issues in a politicized context. Soc Nat Resour 29(11):1263–1279

Watson I (2017) What is the mainstream? The laws of first nations peoples. In: Levy R, O’Brien M, Rice S (eds) New directions for law in Australia: essays in contemporary law reform. Australian National University Press, Canberra, pp 213–220