Abstract

In the social sciences, adolescents’ interest in social and political issues and their participation has been a subject of controversy. While there is an ongoing public debate about young people’s lack of political engagement, many social and political processes depend on participation. For this reason, we should consider whether and how young people get involved socially or politically and how important future participation is to them. In this study, we analysed whether young people in Vienna are politically or socially engaged and how different factors shape their aim of social and political participation for the future. Therefore, we used data from a five-wave panel study with young people in Vienna. At the beginning of the study period about 3000 respondents participated, the students were attending 8th grade at the Neue Mittelschule (the lower track of lower secondary school) in the 2017–2018 academic year and they were then surveyed annually over the next four years (2019–2022). For the analysis, we used cross-sectional data from the fourth wave (the survey year 2021) to explore the way in which young people considered their political and social engagement. In addition, we used longitudinal data from five waves of the panel survey (2018–2022) to determine how the subjective importance of social and political participation changes over time. Our results show that the different forms of social and political participation varied widely and, based on linear multilevel models with a repeated measurement design, we argue that while sociodemographic factors such as gender and social class are crucial for the youth’s social and political participation, engagement is also shaped by their family resources. In contrast to previous research findings, we found that the importance young people attach to engaging socially and politically decreases between the ages of 15 and 19 years. Our findings reveal new insights for achieving future social and political participation by young people.

Zusammenfassung

In den Sozialwissenschaften wird das Interesse Jugendlicher an sozialen und politischen Themen und ihre Beteiligung kontrovers diskutiert. Während in der öffentlichen Debatte das mangelnde Interesse junger Menschen an Politik beklagt wird, hängen gleichzeitig viele soziale und politische Prozesse und ihre langfristige Entwicklung von ihrer Beteiligung ab. Deshalb ist es wichtig, sich mit der Frage zu beschäftigen, ob und wie sich junge Menschen sozial oder politisch engagieren und ob ihnen das für die Zukunft wichtig ist. In der vorliegenden Studie wird analysiert, ob sich Jugendliche in Wien bereits politisch oder sozial engagiert haben und wie verschiedene Faktoren das Ziel sich sozial und politisch zu beteiligen prägen. Dazu wurden die Daten von fünf Erhebungswellen einer Panelstudie mit jungen Menschen in Wien verwendet. Zu Beginn der Erhebung besuchten die Schüler:innen die sogenannte Neue Mittelschule (8. Klasse) im Schuljahr 2017–2018 in Wien, den niedrigeren Bildungspfad in der Sekundarstufe I. Für die Untersuchung nutzen wir Querschnittsdaten der vierten Welle (Erhebungsjahr 2021), um zu erforschen, auf welche Weise sich die Jugendlichen bereits beteiligt haben, sowie Längsschnittdaten aus fünf Wellen der Panelerhebung (2018–2022), um zu analysieren, wie sich die subjektive Bedeutung von sozialer und politischer Partizipation im Zeitverlauf verändert. Die Ergebnisse zeigen, dass die verschiedenen Formen der sozialen und politischen Partizipation von Jugendlichen sehr unterschiedlich sind und können auf Basis der linearen Mehrebenenmodelle mit wiederholtem Messdesign bestätigen, dass soziodemografische Faktoren wie Geschlecht und soziale Schicht zwar entscheidend für die soziale und politische Partizipation von Jugendlichen sind, diese aber auch von den Ressourcen der Familie geprägt werden. Im Unterschied zu bisherigen Forschungsergebnissen nimmt die Bedeutung, die junge Menschen dem sozialen und politischen Engagement beimessen, mit zunehmenden Alter von 15 bis 19 Jahren ab. Die Ergebnisse liefern neue Erkenntnisse für die Forschung über das Ziel der sozialen und politischen Beteiligung, das Jugendliche für die Zukunft haben.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In recent years, research on youth has shown that young people are becoming less politically engaged (Borg and Azzopardi 2022; Ott et al. 2021; Schneekloth and Albert 2019; Lorenzini and Giugni 2012; de Rijke et al. 2008). Adolescents are turning away from politics, which suggests a loss of trust in political institutions, low levels of social and political participation, and a retreat into the private sphere as a social pattern (Borg and Azzopardi 2022; Flanagan and Levine 2010). Turning away from politics has implications not only for the political system but also for democracy in general (Chapman 2023; Grasso 2016). Schönherr and Zandonella (2016) showed that most young people in Austria have low trust in politics. In addition, a considerable share of the young population believes that the democratic system does not perform well and trusts neither the parliament nor the federal government; however, this sentiment is more salient among young people with fewer financial resources (Heinz and Zandonella 2022, p. 28).

Regarding engagement, politicians have expressed concerns about the low levels of social and political participation of young people (Pfaff 2009). One concern is that the numbers of young members of political parties are very low and declining (Whiteley 2011). This has led to pessimistic assumptions about the lack of social and political engagement among the youth (Hooghe and Boonen 2015). Young people have been accused of not paying sufficient attention to politics and society in general and of being focused more on their own individual preoccupations. On the other hand, during the COVID-19 pandemic, young people provided an impulse to political actions and were socially engaged, which was observed in Austria as various forms of neighbourhood assistance and voluntary civic engagement (Ott et al. 2021).

At the same time, young people shape their own fields of activity and are quite active in achieving social and political goals. Recent research suggests that the willingness of young people to participate socially and politically is becoming increasingly important (Schneekloth and Albert 2019). Moreover, social and political participation is important for personal growth and identity formation during the transition to adulthood. Studies have investigated young people’s goals for the future regarding social or political engagement at a single point in time (Schneekloth and Albert 2019). Nonetheless, longitudinal studies on whether it is important for young people to be socially or politically engaged in the future are scarce. Young people’s goals for the future change, especially during the transition to adulthood. Transitions are often seen as critical life events that tend to be linked with stressful and challenging situations and are always associated with role-taking (Geppert 2017). To understand how complex it is for young people to assess what is important, it is necessary to explore the factors that, over time, influence their goal to participate socially or politically. Therefore, here, we analysed how these goals change with increasing age. Additionally, we examined the relationship between the socioeconomic position of one’s family and the social or political participation of the youth because, as assumed in the literature, young people from privileged families tend to participate more (Quenzel and Hurrelmann 2022; Mays and Hambauer 2017). An understanding of this relationship ideally requires panel data that allows tracking the development of the importance attached to social and political participation over an extended period of time (Finkel 1985).

Sociological research identified status transmission and role modelling as possible reasons for the socioeconomic gap in youth participation (Lechner et al. 2018; Mustillo et al. 2004). Status transmission means that young people with parents of higher socioeconomic status (SES) tend to reach higher SES themselves (Lechner et al. 2018, p. 271). Parents of adolescents with higher SES tend to foster social and political participation because they are more aware of civic engagement, are more socially integrated, and are more likely to be recruited by civic organisations (Wilson 2012). Role modelling implies that parents with higher SES are more likely to participate socially or politically, setting an example for their children (Mustillo et al. 2004).

In this article, we report on a five-year panel study among adolescents in Austria who were asked yearly about different aspects of their lives, focusing on questions about the importance of social or political participation for the future. This study allowed us to detect several factors that influence the youth’s sociopolitical participation over a specific period (2018–2022). We analysed the development over time of the importance young people attach to their future social or political participation. In Austria, crucial decisions are made at the end of lower secondary school, at the relatively tender age of about 14. Earlier, after primary school, around the age of 10, young people are divided into the general track of lower secondary school (the Neue MittelschuleFootnote 1, NMS) and the lower cycle of academic secondary school (the Allgemeinbildende Höhere Schule, AHS). For this study, we considered young people in a transition period from the NMS in Vienna to upper secondary education or vocational training. A closer look at the aim of social or political participation of NMS graduates is needed because this group is considered marginalised (students with low socioeconomic status who also have migration experience and often lack cultural capital) (Geppert 2017). In the public debate, NMS students are often portrayed as a homogeneous and socially disadvantaged group (Vogl et al. 2020a). For this reason, we wished to understand whether they are willing to participate politically. NMS students are more likely to face challenges and, in doing so, are confronted with important political issues which may raise their awareness and foster social and political engagement.

Social and political participation are examined closely in this study. Hence, the social and political participation of young people is first theoretically embedded, and the concepts of political and social participation are clarified to derive hypotheses. Subsequently, we present our data, methods and operationalisations before moving to cross-sectional evaluations of several forms of participation in the fourth wave and to the analysis of the panel’s data (information from all five waves) by linear multilevel models with a repeated measurement design. The article concludes with a brief discussion of the results and a note on limitations.

2 Political and social participation of adolescents

The political culture in modern society is based on participation and demands to be politically informed and interested. As Weiss (2020) argued, participation contributes to the stability of the democratic system. Additionally, individual psychology points to the increasing importance of participation and activity for personality development, especially during adolescence (Roßteutscher 2009).

Societies depend on the involvement of their members because broad support for democratic forms of government is a central prerequisite for a vibrant democracy (Schnaudt and Weinhardt 2018). Young people engage in political participation in moments that enable them to send a political signal on a concrete issue that is important to them (Großegger 2012). Currently, we see this in the support for Fridays for Future. Political participation includes all activities with the aim of influencing political decisions, for example, participation in elections, collecting signatures for a petition, or taking part in demonstrations. By contrast, simply being politically interested is not seen as a form of political participation (van Deth 2009).

2.1 Differences in political and social participation

The literature on political participation (e.g., Gaiser and de Rijke 2022; Ekman and Amnå 2012) distinguishes between conventional forms of participation (e.g., going to the polls), unconventional legal forms of participation (e.g., taking part in a demonstration), and unconventional illegal forms of participation (e.g., squatting). Among conventional forms of participation, elections are the most widespread (Prandner and Grausgruber 2019). Other conventional forms of participation include joining a political party and writing letters to politicians. However, the willingness of young people to participate in such activities is generally low. According to Gaiser and de Rijke (2022), adolescents are more likely to participate in unconventional forms of engagement than adults (who are more likely to participate in conventional forms). They based their argument on analyses of various European countries, using data from the European Social Survey (ESS) of 2016. This contrast between the participation of adolescents and adults also applies to Austria according to Glavanovits et al. (2019), based on the Social Survey Austria (SSÖ) 2016. However, Schnaudt and Weinhardt (2018) highlighted that the classification of conventional participation and unconventional participation is not presented uniformly in the literature and that comparisons between study results should be considered carefully.

Social participation, on the other hand, refers to the multitude of opportunities for young people to engage in various groups in society, such as a football club or charity organisation. Social participation differs from political participation because it explicitly aims to not influence decisions at the political level (van Deth 2009). Thus, social participation is a collective term for forms of participation that describe public and collective action without direct political motivation but which extend beyond the private sphere (Roßteutscher 2009). The Shell Youth Study 2019 showed that young people consider voluntary associations as one of the most important institutions for social participation (Schneekloth and Albert 2019). In this regard, the results of the study ‘Growing up in Germany: Everyday Life’s World (AID:A)’ show that the proportion of young people (aged 18–32) holding positions and functions in associations remained stable between 2009 and 2014 (24 and 23%, respectively). While young men are more often involved in sports associations, young women tend to participate more in music clubs and theatre groups (Gille 2015).

Notwithstanding these definitions, the distinction between social and political participation is not always clear. In research on youth, it is often argued that a narrow understanding of politics or the political should be avoided (Gerdes and Bittlingmayer 2016). In this debate, the concept of ‘subpolitics’ (Beck 1993) is often referred to as indicating that a wide variety of interest groups, social movements, or citizens’ initiatives allow for political participation outside the official system of party politics (Gerdes and Bittlingmayer 2016, p. 58). Therefore, we can argue that there is a boundary between social and political participation.

3 Theory and research questions

3.1 The position in the social space

To analyse the influence on the youth of their goals of social and political participation, we refer to Bourdieu’s (1985) concept of social space. For Bourdieu (1987), society consists of relational social positions, which, in their totality, form a social space. This space is formed by three dimensions: ‘the volume of capital, the structure of capital and the development of these two variables’ (Bourdieu 1987, p. 196). Volume here means the total volume of capital available, whereas structure represents the composition of an individual’s capital (i.e., the relative importance of economic and cultural capital). With the third dimension, Bourdieu captures the shifts in social space over time. The beginning and end positions of individuals in a given social space are directly related (Bourdieu 1987, p. 188). The space, then, is differentiated by social fields (Barlösius 2006, p. 90). In a social field, struggles for power and position take place, whereby capital relationships shape the internal hierarchy of the social field. Barlösius asserts that actors with little capital or with an inappropriate capital structure end up at the bottom of the hierarchy. Those with a lot of capital and in the ideal composition, on the other hand, can occupy the highest positions (Barlösius 2006, p. 115). The field and the capital are, therefore, in a reciprocal relationship (Bourdieu and Wacquant 1996, p. 128) but must be considered in a differentiated way for each social field. This perspective allows us to consider the position of young people in a system of relationships that, in turn, influences their perspectives and aims.

Nevertheless, during the transition to adulthood, young people undergo changes that affect their integration into the social and public space (Soler-i-Martí and Ferrer-Fons 2015, p. 94). The family and home-related aspects influence the development of the interest of young people in society and politics (Benedicto and Morán 2007). Depending on the resources provided by the family, young people attach different levels of importance to future social or political participation.

3.2 Social and political participation and their relationship between sociodemographic characteristics and forms of capital

3.2.1 Sociodemographic characteristics

Age and gender are fundamental factors influencing the social and political participation of young people (Masslo 2010). The willingness to participate socially or politically increases steadily from early childhood to late adolescence (Masslo 2010; Westle 2001). With increasing age, experience and knowledge also increase, which, in turn, makes complex processes easier to understand (Lüdemann 2001). However, the transition to adulthood is characterised by a slowdown or reversal effect due to the fact that, in this period, young people are mostly preoccupied with concerns about getting a job and building a career (Marquis et al. 2022). This is because, after the transition period, the mobility of young people decreases, and they tend to develop personal ties in their neighbourhood and attachments with their local community. This, in turn, fosters involvement in community issues and other forms of political participation (Zmerli et al. 2007). Because the participants in our panel were surveyed while they were in complex transitional periods (completing school or vocational training or having their first intimate relationship experiences), we can assume that the importance they attached to future social or political participation at the time of the survey was lowered (Hypothesis 1).

Research on the social and political participation of youth has yielded different results according to gender depending on the specific forms of participation. While females are more likely to participate in social movement activities, males tend to participate more in radical activities (e.g., spraying logos or blocking traffic) (Hooghe and Stolle 2004). A study conducted by Karp and Banducci (2008) suggests that, among adults males tend to be more interested and participative than females. Research also shows that the importance attached to future social and political participation by young people has increased in recent years. A study based in AustriaFootnote 2 surveyed 23,186 students of all school types in the 8th, 9th, and 10th grades and reported that 42% of young males and 39% of young females considered getting involved in politics as very important or rather important (Jugendforschung Pädagogische Hochschulen Österreichs 2021). The Shell Youth Study carried out in Germany reported that, in 2022, 22% of youth considered it important to be socially or politically engaged, whereas, in 2021, 34% of youth considered this to be very important (Schneekloth and Albert 2019). Regarding gender, being politically engaged was important to 24 and 37% of young males in 2002 and 2015, respectively, but this percentage decreased to 34% in 2019. In this context, the political engagement of young females has become increasingly important in recent years. In 2002, 19% of young females stated that social and political participation was important to them, which increased to 29% in 2015 and to 34% in 2019 (Schneekloth and Albert 2019). Therefore, based on these findings, we can assume that the goal to participate socially or politically in the future is more important for young women than young men (Hypothesis 2).

Moreover, young people are embedded differently in society. Adolescents who live and go to school or work in a given country without being citizens are often excluded from many forms of democratic participation, such as elections. Research has revealed differences in social and political participation according to the migration background of young people (Morales and Giugni 2011; Lopez and Marcelo 2008; Stepick and Stepick 2002). The work of Lopez and Marcelo (2008) demonstrates that immigrant youth are less engaged than the children of immigrants or natives. Moreover, research shows that second-generation youth tend to be more socially and politically engaged than their first-generation counterparts (Lopez and Marcelo 2008; Stepick and Stepick 2002). However, Lorenzini and Giugni (2012) were unable to find differences in the political participation of young people according to their migration background. Because the literature is ambiguous on this point, we cannot deduce a hypothesis concerning migration background.

3.2.2 Social capital

The social-capital perspective emphasises that participation results from connections to others (e.g., in social institutions). Although social institutions may also foster the development of skills and values, it is of key importance that they constitute networks. Connections to others in social institutions make it more likely that one will be invited to engage in civic activities (Brady et al. 1995). Institutions also increase access to information for those who are interested in or seek participation opportunities. During childhood, the parents’ social position is crucial, and there are few opportunities to establish connections to other people and institutions outside the family and school. When adolescents get older and become involved in community and school-based activities, they become more socially integrated. As a result, young people may be disadvantaged because of a less dense network of social contacts. Studies have revealed that people with high social capital increase their capacity for political mobilisation (Teney and Hanquinet 2012). Furthermore, Amnå and Zetterberg (2010) showed that the more social capital a young person possesses, the higher their level of political participation. Therefore, we predict that the importance attached to future social or political participation is higher for adolescents with high social capital compared to those with low social capital (Hypothesis 3a).

3.2.3 Economic capital and cultural capital

Income and wealth influence children’s development, with the poverty of parents reducing young people’s chances of participating in society and politics. Overall, there is a correlation between income and social or political engagement (Westle 2001), just as social position also influences general engagement among young people (Picot 2001). As empirical evidence suggests a positive relationship between the family’s income and engagement (Hart and Gullan 2010), we expect that the importance attached to future social or political participation is higher for adolescents with high economic capital compared to those with low economic capital (Hypothesis 3b).

The social status of parents also affects the educational opportunities of young people, which in turn impacts their social and political participation. Children of wealthy parents are far more likely to achieve higher educational qualifications and generally go through life far more confidently. These factors make it easier for these young people to find their way in politics and also to assert themselves in discussions. However, people of higher social status are more attractive to organisations and are more likely to be asked to participate. They may also be more motivated to engage as they have a greater stake in the community. Consistent with this theme, education is a strong predictor of engagement and other kinds of participation (Putnam 1995).

Cultural capital can at least be partially operationalised through education (Picot 2001, p. 153). Numerous studies have demonstrated that the number of books in the family home is associated with parental education (Martin et al. 1996), and it is commonly interpreted as a proxy for the emphasis the family places on education. The Civic Education Study (CIVED), the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2009 (ICCS 2009), and the International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016 (ICCS 2016) collected data from 14-year-old students from different countries and used the number of books in the family home as an indicator. In this case, CIVED found that the more books young people reported having in their homes, the better they performed on a test of political knowledge (Torney-Purta et al. 2001). Both ICCS (2009) and ICCS (2016) used this same measure and found consistent evidence of a strong relationship between young people’s political knowledge and the number of books in their homes (Schulz et al. 2010, 2018). Therefore, we predict that the importance young people attach to future social or political participation is higher for adolescents with high cultural capital compared to those with low cultural capital (Hypothesis 3c).

4 Data and methods

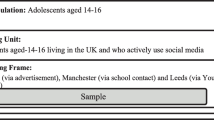

This study is based on longitudinal data from the ‘Pathways to the Future’ project (Flecker et al. 2020, 2023). The survey panel data were collected from 2018 to 2022 from a population of young people who attended an NMS (8th grade) in Vienna in the 2017–2018 academic year. In total, in the baseline, 3078 young people started the survey and 2854 completed it (for further information, see Wöhrer et al. 2023). The sample experienced attrition, and 805 adolescents participated in Wave 2 (Reinprecht et al. 2019), 725 in Wave 3 (Mataloni et al. 2020), 674 in Wave 4 (Flecker et al. 2021), and 451 in Wave 5 (Flecker et al. 2022). The final sample for the longitudinal multivariate analysis conducted in four waves included 659 cases. Furthermore, we included a descriptive analysis of social and political participation using the fourth wave (606 to 609 cases), depending on how many participants answered the questions.

According to official statistics, there were few differences in sociodemographic variables between students at NMS schools in Vienna in the winter term of 2017–2018 and our sample (Vogl et al. 2020b). To manage panel attrition, we referred to Malschinger et al. (in press). To investigate missing cases, we conducted bivariate analyses and logistic regression analyses with dummy-coded dependent variables (e.g., ‘responded W2’ vs ‘missing’ or ‘responded W3’ vs ‘missing’). The relevant variables included in the analysis of missingness were gender, parents’ educational level, migration background, and school grades. Among the variables relevant to this study, only gender was slightly significant in Wave 2. Therefore, we included all the relevant variables in the analysis to lower the risk of biased results (Graham and Donaldson 1993). Overall, the results showed that only missing cases did not have any specific profile in any of the panel’s waves and are thus considered to be missing at random (MAR).

4.1 Variables

For the longitudinal analysis, we asked the question: ‘When you think about your future, how important or unimportant is it to engage yourself socially or politically?’ Responses to this question served as a dependent variable, which was available for four waves. The response options were: ‘very important’, ‘rather important’, ‘rather not important’, ‘very unimportant’, ‘don’t know’ and ‘I would not like to answer’. We excluded the response options: ‘don’t know’ and ‘I would not like to answer’. Therefore, the scale for this variable ranged from 1 (very important) to 4 (very unimportant).Footnote 3

Age was constructed with month and year of birth, whereby young people between the ages of 15 and 19 were observed over time.Footnote 4

Respondents were asked about their gender and were able to choose among ‘male’, ‘female’, ‘I can’t or won’t assign me’, and ‘I don’t want to answer’. For our analysis, gender was binary-coded, differentiating between young men and women. The number of cases in the other categories was too small for in-depth analyses.Footnote 5

Migration background was based on questions about the country of birth of the respondent and the country of birth of their parents. The variable was coded 0 for ‘non-migrant (born in Austria with both parents born in Austria)’, 1 for ‘generation 1 (the respondent was not born in Austria)’, 2 for ‘generation 2 (the respondent was born in Austria but both parents were not born in Austria)’ and 3 for ‘generation 2.5 (the respondent was born in Austria but at least one parent was not born in Austria)’.

Cultural capital was constructed on the basis of the parents’ educational level (considering the highest parental educational level: compulsory education, secondary education or higher education), followed by several questions: ‘Does your mother read books?’ and ‘Does your father read books?’ with the following answer options: ‘yes, almost every day’, ‘yes, several times a week’, ‘often, but not every week’, ‘rarely, once or twice a year’, ‘no, never’, ‘don’t know’ and ‘don’t want to answer’. Then, we asked, ‘Do your parents encourage you to read books?’ with ‘yes’, ‘no’, ‘don’t know’, and ‘don’t want to answer’ as answer options, as well as, ‘How often have you visited a museum/theatre/concert/sports event with your parents in the last year?’ with ‘never’, ‘once a year’ and ‘more frequently’ as answer options. Furthermore, we conducted a factorial analysis and categorised the variables into three groups: 1, ‘low cultural capital’; 2, ‘middle cultural capital’; and 3, ‘high cultural capital’. The Cronbach’s alpha was 0.71. This categorization aligns with Bourdieu’s concept of cultural capital, where individuals whose parents have higher education levels, broader cultural knowledge, and greater involvement in cultural practices are considered to possess higher cultural capital.

Social capital was constructed on the basis of the following question: ‘Are there any types of professionals like teachers, police officers, scientists, company leaders, medical doctors, or lawyers in your family or among your acquaintances?’ with ‘yes’ or ‘no’ being the response categories. We summarised the answers and categorised the variables into: 1, ‘low social capital’; 2, ‘middle social capital’; and 3, ‘high social capital’.

Economic capital was constructed on the basis of the question: ‘What is the economic situation in your household?’, whereby the respondents were able to choose between 1 (‘We have too little money, sometimes it is not enough for food’) and 6 (‘We are rich, money doesn’t matter’). We categorised the variables into: 1, ‘low economic capital’; 2, ‘middle economic capital’; and 3, ‘high economic capital’.

Additionally, we included information from the fourth waveFootnote 6 regarding social and political participation for descriptive analysis in the results section. For this, we used the following question: ‘Reflecting on the last 12 months, did you once participate in the following activities?’ The following options were then provided: ‘Did you collect signatures?’, ‘Are you actively involved in the work of an association?’, ‘Did you participate in a demonstration?’, ‘Did you listen at a discussion event?’, ‘Did you attend a party election event?’ and ‘Did you sign a petition?’. The respondents were able to choose one of the following answers: ‘yes’, ‘no’, or ‘I don’t want to answer’. Regarding the explanations of social and political participation mentioned in the section ‘Differences in political and social participation’ and the wording of the individual items, we should note that not all response options could be clearly assigned to social or political participation. While the possibility to participate in an election event of a party can be assigned to political participation, signing a petition or being involved in an association can mean both social and political participation.

For an overview of the distribution (including frequency and missing values) of the variables in the total sample, we include the descriptive statistics for the longitudinal analysis (Table A1), as well as that for the cross-sectional analysis (Table A2) in the online AppendixFootnote 7.

4.2 Analytical strategy

We present descriptive evaluations of the cross-sectional analysis of different forms of social and political participation in the fourth wave of the survey, which provides information on how young people have already engaged in such activities.

Analyses based on linear multilevel models with a repeated measurement design (Hoffman 2015) (Level 1—time and Level 2—individuals) are presented. We analysed the data using the ‘mixed’ command in Stata. The models contain a mixture of fixed and random effects. The fixed effects refer to the predictors that are present in regular linear regression, whereas the random effects comprise the ‘grouping’ variables that allowed us to obtain a measure of the variability across groups. Therefore, the mixed effect approach accounts for the fact that individuals were measured repeatedly over time by modelling the intercept and time coefficients as random variables. This allowed us to estimate a mean trajectory for the entire sample as well as subject-specific deviations from the mean for each person in the data. The mean trajectory parameters for the whole sample are commonly referred to as ‘fixed effects’. These fixed effects—which are most commonly the intercept, time, and any time-varying covariates—can also be included in the random effects portion of the model. Random effects capture how much the estimates for a particular person differ from the fixed effect estimate, which allows the growth trajectory to differ for each person (Hair and Fávero 2019).

The models considered the fact that individual status scores at different ages are nested within the individual. Therefore, we first calculated the random slope model. Then, we constructed the growth curve models for analysing the change over time in the importance of future social and political participation.

5 Results

5.1 Level of social and political participation in the cross-section

The results show that the frequencies of participation among the respondents differed according to the participation activities (Fig. 1). Over a quarter of the participants signed a petition and over a fifth listened to a discussion event or attended a party election event, whereas 9% were actively involved in the work of an association and 4% collected signatures. Previous studies have shown that the forms of participation for young people in Austria differ considerably. For instance, Heinz and Zandonella (2022) conducted a study about young people and democracy in Austria and included 323 cases of 16- to 26-year-olds in 2022; Schönherr and Zandonella (2016) in their study entitled ‘Generation What’ included 35,285 cases of 18- to 34-year-olds. However, the level of participation in our study was lower compared to these examples. This is perhaps due to our focus on a particular youth population: NMS students in Vienna. Furthermore, the wording of the questions and response options in this study are only roughly comparable with those of previous reports. Additionally, as the fourth wave of our project was conducted in 2021, the question referred to the year 2020, which was marred by the COVID-19 pandemic. Because several forms of participation were restricted in those years due to contact restrictions in Austria, the obtained results can only be compared with previous years to a limited extent.

5.2 Differences in the importance attached to future social or political participation

Table 1 shows the results of the longitudinal analysis of the importance attached to future social or political participation. The analysis was carried out using the sociodemographic variables from the first wave of the project and the repeated measurement of the dependent variable (the goal of future social or political participation) from the second to the fifth wave. Because of the extensive analysis, we only illustrate selected models and present a model comparison in Table 2. Model 0 shows that both within-person and between-person standard deviations were significant (p < 0.001). Furthermore, the intraclass correlation (ICC) of the empty model was calculated and suggested that approximately 39% of the variance was between persons and 61% was within persons.

In Model 1, the predictor age was added, and the model fit improved significantly (χ2 = 13.3, p < 0.001) compared to the empty model (Model 0), indicating the importance of age and individual development over time (Table 2). As young people get older, social or political participation becomes less important for the future (Model 1, Table 1).

Model 2 includes gender and migration background to determine whether the levels of importance of social and political participation differ between males and females or between people with different migration backgrounds. Model fit improved compared to previous models (χ2 = 20.3, p < 0.001, Table 2). Table 1 shows that women find future political and social participation more important than men.

Model 3 includes the three forms of capital: cultural, economic, and social. With this model, the fit improves compared to previous models (χ2 = 24.3, p < 0.001, Table 2), and we observed the significance of cultural and social capital in explaining the differences in the importance given to social and political participation in the future. Table 1 shows that the lower the cultural capital of the youth, the less important future social or political participation is compared with those with middle or high cultural capital. The results are similar for young people with low social capital.

5.3 Development of the importance attached to future social or political participation for age, gender, cultural capital, and social capital

Table 1 shows that age, gender, cultural capital, and social capital are statistically significant in explaining why young people vary in their initial level and development of goals for social or political participation. For a more detailed analysis, we estimated several interactions and calculated the predictive probabilities (see Figs. 2, 3, 4 and 5). The importance of future social or political participation decreases with increasing age, and the results confirm a non-linear progression. This can be seen in Fig. 2, where age is shown on the x‑axis and the importance of future social or political participation is shown on the y‑axis, with 1 meaning ‘very important’ and 4 meaning ‘very unimportant’. From ages 15 to 16, the importance of future social or political participation decreases, from ages 16 to 17, it remains stable, and then it decreases again until the age of 19.

Furthermore, we estimated the interaction age * gender to examine how the importance of future social and political participation over time differed between males and females. Figure 3 displays the predicted values for age and gender over time. Between the ages of 15 and 19, young women attach a higher level of importance to future social or political participation than young men. While the importance of future participation of young men decreases steadily, for young women, the importance of participation increases at the age of 17 and decreases afterwards as they get older.

To examine how the importance of future political and social participation over time differed between the significant types of capital, the interactions age * cultural capital (Model 5, Table 2) and age * social capital (Model 6, Table 2) were estimated and visually illustrated (Figs. 4 and 5). Figure 4 displays the predicted values for the interaction age * cultural capital. Between the ages of 15 and 18, the importance of future social or political participation is higher for young people with high cultural capital compared to those with middle or low cultural capital. The importance that young people with middle and high cultural capital attach to future participation decreases steadily with increasing age; however, for adolescents with low cultural capital, this importance increases at age 18 but then decreases again.

In this context, Fig. 5 clearly shows that the importance of future social or political participation differs according to the social capital of young people and changes over time, whereby we cannot make a statement for high social capital (see Table 1). At the age of 15, the importance of future social or political participation is higher for young people with middle social capital compared to those with low social capital. While at the age of 16 to 17, the importance attached to future social or political participation doesn’t change for young people with low social capital, it increases slightly for young people with middle social capital. Overall, the importance of future social or political participation is higher at the age of 15 than at 19 for young people with low and middle social capital (Fig. 5).

6 Discussion and conclusion

This study examined the development over four years (2019 to 2022) of the subjective importance young people attach to future social or political participation. The results show that for ages 15 to 19, the importance of future social or political participation decreases over time. While previous research has shown that social or political participation tends to increase with age (Westle 2001; Lüdemann 2001), some studies have pointed out that the transition to adulthood is generally characterised by a slowdown or reversal in this upward trend (Marquis et al. 2022). This corresponds to a transition period where young adults are mostly preoccupied with education, finding a job, having a partner, and adapting to ‘adult roles’ (García-Albacete 2014). The specific group we analysed was young people who attended the lower track of lower secondary school in Austria. This population was already facing difficult decisions not only in terms of their studies but also, at least partly, in terms of their career choices and employment. By contrast, young people in the academic tracks still had several years of study left without having to face such decisions. It is surprising that in the group which is more confronted with societal realities the importance attached to future social or political participation is decreasing. The reason could be that life spheres in which they face challenges take priority over politics. Another reason could be that, overall, NMS students have lower socioeconomic status, often come from migrant families, and do not have voting rights. These characteristics may contribute to one considering social and political participation as less important endeavours (Lorenzini and Giugni 2012). An additional factor that cannot be ignored is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic because we could not discern the effect of age from that of the period of analysis. Overall, regarding our first hypothesis, our results support the assertion that, among the group under investigation, the importance attached to future social or political participation decreases during the transition into adulthood.

While previous general research has shown that social or political participation is considerably lower among women than among men, both in terms of actual political participation and willingness to participate, studies focusing on youth have reported varying results depending on the different forms of participation (Gille 2015; Schnaudt and Weinhardt 2018). In our research, the question refers to both social and political participation in general and, as seen in recent years (Schneekloth and Albert 2019), the importance of social or political participation has increased significantly for women. In this respect, our results also support our second hypothesis, suggesting that the importance of future social or political participation is higher for young women than for young men.

The next step focused on the economic, social, and cultural capital that young people acquire through their families, which, according to Bourdieu (1985), determines the position of individuals in their given social space. Previous research has indicated the influence of the parents’ income on the social and political participation of young people (Hart and Gullan 2010; Westle 2001); thus, we initially assumed that the importance young people with financial problems attach to participation would be lower compared to those without financial worries. However, our analysis does not confirm this postulate. Neither is it more important for young people with higher economic capital to participate socially or politically compared to those with less economic capital, nor is economic capital a significant factor that influences the respondent’s aim of participation. Therefore, our results do not support Hypothesis 3b.

Moreover, the analysis indicates that cultural and social capital are necessary when explaining the importance young people attach to future social or political participation. The results show that future participation is more important for young people with higher levels of cultural and social capital. Young people with low social capital, on the other hand, consider it less important to participate. Therefore, following Putnam (1995), having poor social networks yields lower levels of social trust and social and political engagement. This also relates to cultural capital as studies have demonstrated that the social position and educational level of the parents influence social, political and general engagement among young people (Picot 2001). One reason is that a higher level of parental education helps provide youth with the skills needed to participate and engage socially and politically (Zukin et al. 2006). Our results point in the same direction in that they support Hypotheses 3a and 3c, meaning that high social and cultural capital leads to higher importance attached to future social or political participation.

In sum, the findings show that, for (former) NMS students in Vienna, results reported by studies on youth in general are applicable to the special group under investigation in our study. This means that even among less privileged and often migrant youth, the cultural and social capital of one’s parents matters when it comes to the social and political engagement of young people. Interestingly, when controlling for the different types of capital, migration status did not make any difference. The importance this group of youth attach to social and political participation decreases continuously during the transition from adolescence to adulthood. Interestingly, this is also the time when young people acquire the right to vote or experience exclusion from voting because of their lack of citizenship. Neither being faced with the challenges of making decisions nor the difficulties of transitions seem to strengthen the goal of political participation.

This study contributes to a better understanding of how the sociodemographic profile of young people, along with their diverse forms of capital, influences the significance they place on future social or political participation. It clearly points out the importance of social and cultural capital and, based on longitudinal data, is able to show what changes occur during important transitions within education system or from school to vocational training.

While this paper contributes to research on young people’s social and political participation, it is also necessary to point out several limitations. We explored the relationship and correlation of our dependent variable with other questions on social or political participation in the fourth wave of the project. Although the results show a high correlation and suggest that the indicator used was valid for these analyses, we could not discern between the effects of age and that of the period of analysis since the latter was affected by a significant crisis: the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic has had a profound impact on young people, potentially shaping their perception of the significance of social and political engagement (Marquis et al. 2022; Ott et al. 2021). This demonstrates that social and political participation is occasionally shaped by external conditions and the presence of public discourses. Therefore, future research would benefit from analysing extended observation periods, considering current social debates and political situations.

The operationalisation of the economic, social, and cultural capital is based on one’s family. Hence, because young people have not yet acquired these forms of capital by themselves, the information used was solely from the first wave. Moreover, the operationalisation of economic capital is based on a single variable and this can affect the results by reducing the significance and correlation between economic capital and the importance of social or political engagement.

Furthermore, this analysis focused on a specific group of young people, namely those who attended NMS (the lower track of lower secondary school). Thus, we cannot generalise the obtained results for the entire population of young people in Vienna. During the survey period (2018–2022), these young people were eligible to vote for the first time. Considering the different conditions for participation in Austrian elections (federal, provincial or municipal elections) and the lack of information on whether and when panel participants voted, this information could not be included in the analysis.

Notes

Starting the school year 2020/21, Mittelschule (MS) has replaced Neue Mittelschule (NMS) as the compulsory school for 10- to 14-year-olds.

(https://www.bmbwf.gv.at/dam/jcr:7b6de1bc-36c1-4b54-88f0-7683120238d0/mittelschule_2020.pdf).

Lebenswelten 2020: Werthaltungen junger Menschen in Österreich.

To validate this variable as an indicator of social and political engagement, we explored the correlation of this variable with other questions on social or political participation in the fourth wave of the project, for instance, ‘Political interest’, ‘High understanding and assessment of political issues’ or ‘Confident to actively participate in conversations about politics’. The results show a moderate-to-high positive significant (p < 0.01) correlation with the different variables.

Because of the small number of young people aged 20 to 22, they were not taken into account for the longitudinal evaluations (58 individuals were excluded).

In total, 13 cases answered that they cannot or do not want to assign themselves, whereas 27 gave no answer.

Survey period from March 2021 to May 2021.

Online Appendix available here: https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:1660922.

References

Amnå, Erik, and Pär Zetterberg. 2010. A Political Science Perspective on Socialization Research: Young Nordic Citizens in a Comparative Light. In Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth, ed. Lonnie R. Sherrod, Judith Torney-Purta, and Constance A. Flanagan, 43–66. Hoboken: Wiley.

Barlösius, Eva. 2006. P. Bourdieu. Frankfurt am Main, New York: Campus.

Beck, Ulrich. 1993. Die Erfindung des Politischen. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Benedicto, Jorge, and Maria Luz Morán. 2007. Becoming A citizen: analysing the social representations of citizenship in youth. European Societies 9:601–622.

Borg, Maria, and Andrew Azzopardi. 2022. Political interest, recognition and acceptance of voting responsibility, and electoral participation: young people’s perspective. Journal of Youth Studies 25:487–511.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1985. The forms of social capital. In Handbook of theory and research for the sociology of education, ed. John Richardson, 241–258. New York: Greenwood.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1987. Die feinen Unterschiede: Kritik der gesellschaftlichen Urteilskraft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Bourdieu, Pierre, and Loic J.D. Wacquant. 1996. Die Ziele der reflexiven Soziologie. In Reflexive Anthroplogie, ed. Pierre Bourdieu, Loic J.D. Wacquant, 95–251. Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Schlozman. 1995. Beyond SES: a resource model of political participation. American Political Science Review 89:271–294.

Chapman, Amy L. 2023. Social media for civic education: engaging youth for democracy. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan.

van Deth, Jan W. 2009. Politische Partizipation. In Politische Soziologie, ed. Viktoria Kaina, Andrea Römmele, 141–161. Wiesbaden: VS.

Ekman, Joakim, and Erik Amnå. 2012. Political participation and civic engagement: towards a new typology. Human Affairs 22:283–300.

Finkel, Steven E. 1985. Reciprocal effects of participation and political efficacy: a panel analysis. American Journal of Political Science 29:891–913.

Flanagan, Constance, and Peter Levine. 2010. Civic engagement and the transition to adulthood. The Future of Children 20:159–179.

Flecker, Jörg, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder. 2020. Jugendliche am Ende der NMS: Heterogenität, soziale Ungleichheit und Agency. In Wege in die Zukunft: Lebenssituationen Jugendlicher am Ende der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder, 305–328. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737011457.305.

Flecker, Jörg, Paul Malschinger, and Brigitte Schels. 2021. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave4. Institut für Soziologie, Universität Wien. Forschungsprojekt.

Flecker, Jörg, Paul Malschinger, Brigitte Schels, and Ona Valls. 2022. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave5. Institut für Soziologie, Universität Wien. Forschungsprojekt.

Flecker, Jörg, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer (eds.). 2023. Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule. V&R unipress, Vienna University Press.

Gaiser, Wolfgang, and Johann de Rijke. 2022. Politische Orientierungen und Partizipation junger Menschen in Europa – Empirische Ergebnisse und Thesen zu einem komplexen Them. In Jugend – Lebenswelt – Bildung: Perspektiven für die Jugendforschung in Österreich Schriftenreihe der ÖFEB-Sektion Sozialpädagogik., ed. Fred Berger, Flavia Guerrini, Birgit Bütow, Helmut Fennes, Karin Lauermann, Stephan Sting, and Natalia Wächter, 133–150. Opladen Berlin Toronto: Barbara Budrich.

García-Albacete, Gema M. 2014. Young people’s political participation in Western Europe: continuity or generational change? Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Geppert, Corinna. 2017. SchülerInnen an der Bildungsübertrittsschwelle zur Sekundarstufe I: Übertritts- und Verlaufsmuster im Kontext der Neuen Mittelschule in Österreich. Budrich UniPress.

Gerdes, Jürgen, and Uwe H. Bittlingmayer. 2016. Jugend und Politik. Soziologische Aspekte. In Jugend und Politik – Politische Bildung und Beteiligung von Jugendlichen, ed. Aydin Gürlevik, Klaus Hurrelmann, and Christian Palentien, 45–67. Wiesbaden: Springer VS.

Gille, Martina. 2015. Sind junge Menschen heute vereinsmüde? Vereinsaktivitäten und Vereinsengagement von Jugendlichen und jungen Erwachsenen zwischen 2009 (AID:A I) und 2014/15 (AID:A II). In Aufwachsen in Deutschland heute. Erste Befunde aus dem DJI-Survey, ed. Sabine Walper, Walter Bien, and Thomas Rauschenbach, 46–50. München: Deutsches Jugendinstitut e. V..

Glavanovits, Johann, Johann Gründl, Sylvia Kritzinger, and Patricia Oberluggauer. 2019. Politische Partizipation. In Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich, ed. Johann Bacher, Alfred Grausgruber, Max Haller, Franz Höllinger, Dimitri Prandner, and Roland Verwiebe, 439–456. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-21081-6_18.

Graham, John W., and Stewart I. Donaldson. 1993. Evaluating interventions with differential attrition: The importance of nonresponse mechanisms and use of follow-up data. Journal of Applied Psychology 78(1):119–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.78.1.119.

Grasso, Maria T. 2016. Generations, political participation and social change in Western Europe. London: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Großegger, Beate. 2012er. Wo sind die jungen WutbürgerInnen? Auf den Spuren protestbewegungsorientierter Jugendlicher der 2012er Jahre. Wien: Institut für Jugendkulturforschung. https://www.jugendkultur.at/wp-content/uploads/Junge-wutbuergerInnen_grossegger_2012.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Hair, Joseph F., and Luiz Paulo Fávero. 2019. Multilevel modeling for longitudinal data: concepts and applications. RAUSP https://doi.org/10.1108/RAUSP-04-2019-0059.

Hart, Daniel, and Rebecca Lakin Gullan. 2010. The sources of adolescent activism: historical and contemporary findings. In Handbook of research on civic engagement in youth, ed. Lonnie R. Sherrod, Judith Torney-Purta, and Constance Flanagan, 67–90. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Heinz, Janine, and Martina Zandonella. 2022. Junge Menschen und Demokratie in Österreich 2022. Wien: SORA. https://www.parlament.gv.at/dokument/fachinfos/publikationen/SORA_Bericht-Parlament-Junge-Menschen-und-Demokratie-2022.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Hoffman, Lesa. 2015. Longitudinal analysis: modeling within-person fluctuation and change. London, New York: Routledge.

Hooghe, Marc, and Joris Boonen. 2015. The Intergenerational transmission of voting intentions in a multiparty setting: an analysis of voting intentions and political discussion among 15-year-old adolescents and their parents in Belgium. Youth & Society 47:125–147.

Hooghe, Marc, and Dietlind Stolle. 2004. Good girls go to the polling booth, bad boys go everywhere: gender differences in anticipated political participation among American fourteen-year-olds. Women & politics 26(3–4):1–23.

Jugendforschung Pädagogische Hochschulen Österreichs. 2021. Lebenswelten 2020: Werthaltungen junger Menschen in Österreich. Innsbruck Wien: Studien Verlag.

Karp, Jeffrey A., and Susan A. Banducci. 2008. When politics is not just a man’s game: women’s representation and political engagement. Electoral Studies 27:105–115.

Lechner, Clemens M., Maria K. Pavlova, Florencia M. Sortheix, Rainer K. Silbereisen, and Katariina Salmela-Aro. 2018. Unpacking the link between family socioeconomic status and civic engagement during the transition to adulthood: Do work values play a role? Applied Developmental Science 22:270–283.

Lopez, Mark Hugo, and Karlo Barrios Marcelo. 2008. The civic engagement of immigrant youth: new evidence from the 2006 civic and political health of the nation survey. Applied Developmental Science 12:66–73.

Lorenzini, Jasmine, and Marco Giugni. 2012. Employment status, social capital, and political participation: a comparison of unemployed and employed youth in geneva. Swiss Political Science Review 18(3):332–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1662-6370.2012.02076.x.

Lüdemann, Christian. 2001. Politische Partizipation, Anreize und Ressourcen. Ein Test verschiedener Handlungsmodelle und Anschlußtheorien am ALLBUS. In Politische Partizipation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Empirische Befunde und theoretische Erklärungen, ed. Achim Koch, Martina Wasmer, and Peter Schmidt, 43–71. Wiesbaden: VS.

Malschinger, Paul, Susanne Vogl, and Brigitte Schels. 2023. Drop in, drop-out, or stay on: Patterns and predictors of panel attrition among young people. Österreichische Zeitschrift für Soziologie In press. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00545-z.

Marquis, Lionel, Ursina Kuhn, and Gian-Andrea Monsch. 2022. Patterns of (de)politicization in times of crisis: Swiss residents’ political engagement, 1999–2020. Frontiers in Political Science 4:1–20.

Martin, Michael O., Ina V.S. Mullis, Albert E. Beaton, Eugenio J. Gonzales, Teresa A. Smith, and Dana L. Kelly. 1996. Science achievement in the middle school years: IEA’s third international mathematics and science study (TIMSS). Chestnut: Center for the Study of Testing, Evaluation, and Educational Policy, Boston College. eds. International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement.

Masslo, Jens. 2010. Jugendliche in der Politik: Chancen und Probleme einer institutionalisierten Jugendbeteiligung am Beispiel des Kinder- und Jugendbeirates der Stadt Reinbek. Wiesbaden: VS.

Mataloni, Barbara, Molina Xaca Camoli, and Christoph Reinprecht. 2020. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave3. Institut für Soziologie, Universität Wien. Forschungsprojekt.

Mays, Anja, and Verena Hambauer. 2017. Sozioökonomischer Status und politisches Engagement: Warum wir mehr politische Bildung in Kindheit und Jugend brauchen. In 1917 bis 2017: 100 Jahre Links, ed. Franz Walter, 137–145. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht.

Morales, Laura, and Marco Giugni. 2011. Social capital, political participation and migration in Europe: making multicultural democracy work? New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Mustillo, Sarah, John Wilson, and Scott M. Lynch. 2004. Legacy volunteering: a test of two theories of intergenerational transmission. Journal of Marriage and Family 66:530–541.

Ott, Martina, Herbert Gabriel, Paul Resinger, and Daniel Wutti. 2021. Politik, Demokratie und Zusammenleben von Menschen aus unterschiedlichen Herkunftsländern. In Lebenswelten 2020: Werthaltungen junger Menschen in Österreich, ed. Jugendforschung Pädagogische Hochschulen Österreichs, 151–188. Innsbruck Wien: Studien Verlag.

Pfaff, Nicolle. 2009. Youth culture as a context of political learning: How young people politicize amongst each other. YOUNG 17:167–189.

Picot, Sibylle. 2001. Jugend und freiwilliges Engagement. In Freiwilliges Engagement in Deutschland, ed. Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend, 111–207. https://www.bmfsfj.de/resource/blob/176836/7dffa0b4816c6c652fec8b9eff5450b6/frewilliges-engagement-in-deutschland-fuenfter-freiwilligensurvey-data.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Prandner, Dimitri, and Alfred Grausgruber. 2019. Politische Involvierung in Österreich: Interesse an Politik und politische Orientierungen. In Sozialstruktur und Wertewandel in Österreich, ed. Johann Bacher, Alfred Grausgruber, Max Haller, Franz Höllinger, Dimitri Prandner, and Roland Verwiebe, 389–410. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Putnam, Robert David. 1995. Bowling alone: America’s declining social capital. Journal of Democracy 6(1):65–78. https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.1995.0002.

Quenzel, Gudrun, and Klaus Hurrelmann. 2022. Lebensphase Jugend: Eine Einführung in die sozialwissenschaftliche Jugendforschung. Weinheim Basel: Beltz Juventa.

Reinprecht, Christoph, Barbara Mataloni, and Camilo Molina Xaca. 2019. Wege in die Zukunft. Eine Längsschnittstudie über die Vergesellschaftung junger Menschen in Wien. Quantitatives Panel, Wave2. Institut für Soziologie, Universität Wien. Forschungsprojekt.

de Rijke, Johann, Wolfgang Gaiser, and Franziska Waechter. 2008. Political orientation and participation—a longitudinal perspective. In Youth and political participation in Europe: results of the comparative study EUYOUPART, ed. Reingard Spannring, Günther Ogris, and Wolfgang Gaiser, 121–147. Leverkusen, Opladen: Barbara Budrich.

Roßteutscher, Sigrid. 2009. Soziale Partizipation und Soziales Kapital. In Politische Soziologie, ed. Viktoria Kaina, Andrea Römmele, 163–180. Wiesbaden: VS.

Schnaudt, Christian, and Michael Weinhardt. 2018. Blaming the young misses the point: re-assessing young people’s political participation over time using the ‘identity-equivalence procedure. Methods, data, analyses 12(2):309–334. https://doi.org/10.12758/mda.2017.12.

Schneekloth, Ulrich, and Mathias Albert. 2019. Jugend und Politik: Demokratieverständnis und politisches Interesse im Spannungsfeld von Vielfalt, Toleranz und Populismus. In Jugend 2019. Eine Generation meldet sich zu Wort, ed. Shell Deutschland Holding, 47–101. Weinheim Basel: Beltz.

Schönherr, Daniel, and Martina Zandonella. 2016. Generation What. Wien: SORA. https://zukunft.orf.at/rte/upload/isabelle/orf_publicvalue_generation_what_ansicht_2021nov16.pdf. Accessed 14 June 2023.

Schulz, Wolfram, John Ainley, Julian Fraillon, David Kerr, and Bruno Losito. 2010. ICCS 2009 international report: civic knowledge, attitudes, and engagement among lower-secondary students in 38 countries. Amsterdam: IEA.

Schulz, Wolfram, John Ainley, Julian Fraillon, Bruno Losito, Gabriella Agrusti, and Tim Friedman. 2018. Becoming citizens in a changing world: IEA international civic and citizenship education study 2016 international report. Cham: Springer.

Soler-i-Martí, Roger, and Mariona Ferrer-Fons. 2015. Youth participation in context: the impact of youth transition regimes on political action strategies in Europe. The Sociological Review 63:92–117.

Stepick, Alex, and Carol Dutton Stepick. 2002. Becoming American, constructing ethnicity: immigrant youth and civic engagement. Applied Developmental Science 6:246–257.

Teney, Celine, and Laurie Hanquinet. 2012. High political participation, high social capital? A relational analysis of youth social capital and political participation. Social Science Research 41:1213–1226.

Torney-Purta, Judith, Rainer Lehmann, Hans Oswald, and Wolfram Schulz. 2001. Citizenship and education in twenty-eight countries: civic knowledge and engagement at age fourteen. Amsterdam: IEA.

Vogl, Susanne, Michael Parzer, Franz Astleithner, and Barbara Mataloni. 2020a. Heterogenität am Ende der NMS: Unterschiedliche Ausgangspositionen Jugendlicher. In Wege in die Zukunft. Lebenssituationen Jugendlicher am Ende der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder, 87–118. Göttingen: V&R Unipress. https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737011457.87.

Vogl, Susanne, Veronika Wöhrer, and Andrea Jesser. 2020b. Das Forschungsdesign der ersten Welle des Projekts „Wege in die Zukunft“. In Wege in die Zukunft. Lebenssituationen Jugendlicher am Ende der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Veronika Wöhrer, and Irene Rieder, 59–86. Göttingen: V&R unipress. https://doi.org/10.14220/9783737011457.59.

Weiss, Julia. 2020. What is youth political participation? Literature review on youth political participation and political attitudes. Frontiers in Political Science 2:1–13.

Westle, Bettina. 2001. Politische Partizipation und Geschlecht. In Politische Partizipation in der Bundesrepublik Deutschland. Empirische Befunde und theoretische Erklärungen, ed. Achim Koch, Martina Wasmer, and Peter Schmidt, 131–168. Wiesbaden: VS.

Whiteley, Paul F. 2011. Is the party over? The decline of party activism and membership across the democratic world. Party Politics 17:21–44.

Wilson, John. 2012. Volunteerism research: a review essay. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly 41:176–212.

Wöhrer, Veronika, Susanne Vogl, Brigitte Schels, Barbara Mataloni, Paul Malschinger, and Franz Astleithner. 2023. Methodische Grundlagen und Forschungsdesign der Panelstudie. In Junge Menschen gehen ihren Weg. Längsschnittanalysen über Jugendliche nach der Neuen Mittelschule, ed. Jörg Flecker, Brigitte Schels, and Veronika Wöhrer, 29–58. Göttingen: V&R Unipress.

Zmerli, Sonja, Kenneth Newton, and Jose Ramon Montero. 2007. Trust in people, confidence in political institutions, and satisfaction with democracy. In Citizenship and involvement in European democracies: a comparative analysis, ed. Jan W. van Deth, José R. Montero, and Anders Westholm, 35–65. New York: Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

Zukin, Cliff, Scott Keeter, Molly Andolina, Krista Jenkins, and Michael X. Delli Carpini. 2006. A new engagement? Political participation, civic life, and the changing American citizen. Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Department of Sociology at the University of Vienna and the members of the steering committee of the Pathways to the Future project (PI Jörg Flecker). In addition, we would like to thank the editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments.

Funding

The “Pathways to the Future” project was conducted in co-operation with and partly financially assisted by the University of Vienna (Department of Sociology), Chamber of Labour Vienna, the Vienna Employment Promotion Fund (WAFF), the Federal Ministry for Education, Science and Research and the Federal Ministry for Labour and Economy.

Funding

Open access funding provided by University of Vienna.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

P. Malschinger, O. Valls and J. Flecker declare that they have no competing interests.

Additional information

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available online under https://phaidra.univie.ac.at/o:166092 in the format provided by the authors (unedited).

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Malschinger, P., Valls, O. & Flecker, J. Growing into participation? Influences on youth’s plans to engage socially or politically and their changes over time. Österreich Z Soziol 48, 381–404 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00543-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11614-023-00543-1