Abstract

Background

It is uncertain if the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) 2013 guidelines for the use of HMGCoA reductase inhibitors (statins) were associated with increased statin eligibility and prescribing across underserved groups.

Objective

To analyze, by race, ethnicity, and preferred language, patients with indications for and presence of a statin prescription before and after the guideline change.

Design

Retrospective cohort study.

Setting

Multistate community health center (CHC) network with linked electronic health records.

Patients

Low-income patients aged ≥ 50 with a primary care visit in 2009–2013 or 2014–2018.

Main Measures

(1) Odds of each race/ethnicity/language group meeting statin eligibility via the National Cholesterol Education Program Adult Treatment Panel III Guidelines in 2009–2013 or the ACC/AHA guidelines in 2014–2018. (2) Among those eligible, odds of each group in each period with a statin prescription.

Key Results

In 2009–2013 (n = 109,330), non-English-preferring Latino (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.03, 1.17), White (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.72), and Black patients (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.11, 1.42), were more likely than English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites to meet guideline criteria for statins. Non-English-preferring Black patients, when eligible, were no more likely than non-Hispanic Whites to have statin prescriptions (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.88, 1.54). In 2014–2018 (n = 319,904), English-preferring Latino patients (OR = 1.02, 95% CI = 0.96–1.07) and non-English-preferring Black patients (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.98, 1.19) had similar odds of statin prescription to English-preferring non-Hispanic White patients. English-preferring Black patients were less likely (OR = 0.95, 95% CI = 0.91–0.99) to have a prescription than English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites.

Conclusion

Across the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline change in CHCs serving low-income patients, non-English-preferring patients were consistently more likely to be eligible for and have been prescribed statins. English-preferring Latino and English-preferring Black patients experienced reduced prescribing, comparatively, after the guideline change. Further work should explore the contextual factors that may influence guideline effectiveness and care equity.

Similar content being viewed by others

INTRODUCTION

Cardiovascular disease is the number one cause of death in the United States (US).1,2 Non-White populations have been shown to experience higher cardiovascular morbidity and mortality and high prevalence and poorer control of cardiovascular risk factors.3,4 A large proportion of non-White patients have documented risk factors for cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction, stroke), but control/optimization of these risk factors has been shown to be poorer in these groups than in non-Hispanic Whites.5,6,7 Screening for and treating these risk factors is the subject of evidence-based guidelines.8 Particularly, HMG CoA reductase inhibitors (statins) are recommended for the treatment of hyperlipidemia to reduce the risk of poor cardiovascular outcomes.8 While these medications have been used for multiple decades, there is substantial survey—based evidence that racial and ethnic minority patients with indications for these medications may not receive them.9,10,11,12,13,14,15 For instance, studies of statin prescribing in various Latino subgroups have also yielded conflicting findings, with varying likelihoods of prescribing by place of birth and/or subgroup,10,16,17 acculturation/language (some studies associate acculturation with healthcare utilization, others do not),6,14,18,19,20,21 and other social factors.22 Studies have also shown variation in Black-White disparities in statin use 9,12 although few if any studies have examined this prescribing by language, especially over this guideline transition.

Prescribing recommendations for statin medications underwent a transition in 2013, when the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) released guidelines transitioning from the primary use of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) levels 23 to using the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease (ASCVD) pooled cohort risk equation (PCE)8 to establish cutoffs for prescribing. These risk equations included race, in order to improve the risk modification of Black patients who may experience worse cardiovascular outcomes.8 Survey-based research has demonstrated that this change resulted in higher levels of statin eligibility among some patients of color,24 but it is uncertain if the guideline change was associated with changing rates of prescription across different racial and ethnic groups, and whether preferred language is associated with these prescriptions. Additionally, a large proportion of racial and ethnic minority patients are cared for in our nation’s network of community health centers (CHCs).25 In CHCs, English and non-English-preferring Black, Asian, and Latino patients have been shown to be more likely to have documented measures necessary to assess risk and indication for statin use26 while English-preferring Black patients experienced a greater decline in this documentation, compared to English-preferring White patients, over the guideline change. Understanding health care in the CHC setting is crucial to gauge the potential of these guideline changes to improve population-level cardiovascular risk management and whether they mitigate or exacerbate inequity. To address these challenges, using a multi-state, linked electronic health record (EHR) dataset we performed, in low-income patients accessing CHCs, an analysis by race and ethnicity and preferred language among patients with indications for statin prescription before 2014 and patients with indications in 2014 and onward to assess statin prescribing prevalence over this major guideline change. Based on previous work in CHCs,14 we hypothesized that while Latino, Black, and Asian (especially non-English-preferring) patients may have increased eligibility for statin prescriptions after the ACC/AHA guideline change, they will actually be prescribed these medications less than non-Hispanic Whites.

METHODS

Data Source

Data were obtained from EHRs in the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center (ADVANCE) Clinical Research Network (CRN) from the years 2009–2018 and included 556 community health centers in 24 US states (Alaska, California, Colorado, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Indiana, Kansas, Massachusetts, Maryland, Minnesota, Missouri, Montana, North Carolina, New Mexico, Nevada, New York, Ohio, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Carolina, Texas, Washington, Wisconsin). The study sample includes patients 50 years and older at the study start.

Population

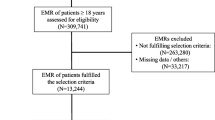

Patients having at least one primary care encounter in the ADVANCE CRN comprised two non-mutually exclusive groups for the periods 2009–2013 and 2014–2018. For the 2009–2013 inclusion, a valid LDL measure was also required. We defined primary care encounters as those occurring with a physician (Allopath, Osteopath, or Naturopath), physician assistant, or nurse practitioner utilizing Current Procedural Terminology codes 99201-99205, 99212-99215, 99241-99245, 99386-99387 and 99396-99397.

Exclusion Criteria

Patients missing race, ethnicity, or sex data in the EHR were excluded, as were self-reported racial groups with sample sizes too small for appropriate statistical inference in this study design. For these reasons, < 1% of patients in both periods were excluded for small race and ethnicity sample size, and approximately 6% and 10% of the eligible patients in the earlier and later periods were excluded respectively for missing race and ethnicity information.

Dependent Variables

We evaluated two outcomes within both periods, each a binary indicator for (1) meeting the period-specific criteria for statin use, and (2) documentation of a statin prescription among those meeting criteria. For the 2009–2013 period, patients were considered to meet statin criteria with (a) LDL ≥ 160 mg/dL, (b) LDL ≥ 130 and smoker, or hypertension, or woman over age 55, or (c) LDL ≥ 100 with diabetes or prior myocardial or cerebral infarction.23 For the 2014–2018 period, criteria were met with (a) a significant coronary, cerebral, or peripheral arterial atherosclerosis event, such as a prior myocardial or cerebral infarction, (b) LDL ≥ 190 mg/dL, (c) diabetes, or (d) PCE ASCVD 10-year risk score ≥ 7.5%.8 To calculate the PCE risk score we adapted code sourced from https://rpubs.com/GintasBu/ASCVD. Scores calculated using patient’s EHR data were then verified against scores generated using the American College of Cardiology’s online risk calculator: https://tools.acc.org/ASCVD-Risk-Estimator-Plus/#!/calculate/estimate/. Of note, guidelines in both eras include the prescription of statins for the primary and secondary prevention of cardiovascular events.

Independent Variables

We examined eight mutually exclusive groups distinguished by self-identified race, ethnicity, and language preference. These included English and non-English-preferring Latino, non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Asian groups. While we use Latino because it is often preferred in our study population, the actual ethnicity information collected by clinics is Hispanic/non-Hispanic.

Covariates

We included multiple potential confounders in our analyses, including patient-level covariates and ASCVD risk factors. Patient age, sex, insurance status during the time period, income relative to 138% of the US federal poverty level during the time period, and visits per year were included, as were obesity, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and diabetes status. Obesity, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia (as ICD-9/10 diagnoses on the problem list) were included as covariates because they may be associated with the collection of data necessary to assess eligibility and perceived cardiovascular risk and prescribing behavior by the provider. Diabetes was included as a covariate in all models except the eligibility model in the 2014–2018 time period, because in that period, diabetes alone was a guideline indication for statin prescription. Patient’s primary clinic state’s 2014 Medicaid expansion status was also included.

Statistical Analysis

We described patient characteristics of the overall sample in both periods and by race/ethnicity/language group. Each outcome was a binary indicator modelled with generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression and robust sandwich variance estimator with exchangeable correlation structure clustered on clinics to account for the clustering of patients within clinics. The GEE estimated adjusted odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported for each group compared to the largest sample group (English-preferring non-Hispanic White). Analyses were conducted in Stata v.15 with two-sided testing and set 5% type I error. The Oregon Health and Science University Institutional Review Board approved this study.

RESULTS

Characteristics of our study population are in Table 1 (2009–2013, N = 109,330) and Table 2 (2014–2018, N = 319,904). Overall, our study groupings had broad similarities in both studied time periods in age, visit numbers per year, proportions of diagnosed hypertension and hyperlipidemia, (both by ICD 9/10 code on the problem list), sex, and income level. The proportion of each group who was never insured decreased in the second period. Non-English-preferring Latinos had a higher proportion of never insured patients than other groups regardless of time period. Asian patients, regardless of language spoken had a lower prevalence of obesity, and Latino and Black patients had a lower prevalence of individuals residing in Medicaid expansion states.

Unadjusted and covariate-adjusted prevalence for statin eligibility in 2009–2013 and 2014–2018, and statin prescriptions in 2009–2013 and 2014–2018, are reported in Appendix Tables 1 and 2. The unadjusted prevalence of statin eligibility in the 2009–2013 period ranged from 47 (English-preferring non-Hispanic White) to 58% (non-English-preferring non-Hispanic White). In that same time period, statin prescriptions among those eligible ranged from 55 (English-preferring non-Hispanic White) to 62% (non-English-preferring Latino). In the period after the guideline change, statin eligibility ranged from 48 (English-preferring non-Hispanic White) to 67% (non-English-preferring non-Hispanic Black). Statin prescriptions after the guideline change period ranged from 52 (English-preferring Non-Hispanic Black) to 63% (non-Enghlish-preferring Asian).

Statin Eligibility Prior to the ACC/AHA Guideline Change (2009–2013)

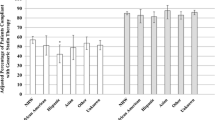

Covariate-adjusted odds ratios of being eligible for statin prescriptions during 2009–2013 are displayed in Fig. 1. Non-English-preferring Latino patients (OR = 1.10, 95% CI = 1.03, 1.17), non-English-preferring non-Hispanic Black patients (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.11, 1.42), and non-English-preferring White patients (OR = 1.41, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.72) had higher odds of being eligible for a statin prescription than non-Hispanic Whites according to guidelines active at the time. English-preferring Latinos (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.08), English-preferring non-Hispanic Black patients (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.97, 1.10), and Asian patients, both English-preferring (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.82, 1.05) and non-English-preferring (OR = 1.04, 95% CI = 0.94, 1.16) had similar odds of statin prescription eligibility as English-preferring non-Hispanic White patients. were as likely to be eligible as English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites. While non-English-preferring non-Hispanic Black (OR = 1.25, 95% CI = 1.11, 1.42) showed higher odds of being eligible for a statin prescription compared to English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites, we observed similar odds between English-preferring non-Hispanic Black and White patients (OR = 1.03, 95% CI = 0.96, 1.09). Among Asian patients, both English-preferring (OR = 0.93, 95% CI = 0.82, 1.05) and non-English-preferring (OR = 1.05, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.17) had similar odds of statin prescription eligibility as English-preferring-non-Hispanic White patients. Lastly, non-English-preferring White patients (OR = 1.42, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.73) had higher odds of being eligible for a statin prescription than English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites.

Covariate-adjusted odds ratios of meeting statin eligibility for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events (above), and for having a documented statin prescription in the EHR if eligible (below), 2009–2013. Note: EHR = electronic health record; GEE = generalized estimating equations; LDL = low-density lipoprotein. The reference group, English-preferring non-Hispanic White adults, is represented by the vertical dotted line at 1.00 on the x-axis. The dots represent the adjusted odds ratio point estimates and the horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals for those estimates. Estimates derived using GEE logistic regression adjusted for patient's sex, age, insurance status, %federal poverty level, diagnosis of diabetes, hypertension, obesity, or hyperlipidemia, primary care utilization, and Medicaid expansion State status with clustering on patient's primary clinic. Statin eligible if LDL ≥ 160 mg/dL; or LDL ≥ 130 mg/dL and smoker, hypertension, or female age 55 + ; or LDL ≥ 100 with cardiovascular disease or diabetes.

Statin Eligibility after the ACC/AHA Guideline Change (2014–2018)

Study findings for statin eligibility for the 2014–2018 time period are displayed in Fig. 2. Compared to English-preferring non-Hispanic White patients, all other groups had increased odds of being eligible for statins after the ACC/AHA guideline change. Specifically, non-English (OR = 1.45, 95% CI = 1.38, 1.53) and English-preferring (OR = 1.27, 95% CI = 1.21, 1.33) Latinos, non-English (OR = 2.56, 95% CI = 2.25, 2.91), and English-preferring (OR = 1.95, 95% CI = 1.86, 2.05) Black patients, non-English (OR = 1.46, 95% CI = 1.33, 1.59) and English-preferring (OR = 1.57, 95% CI = 1.44, 1.71) Asian patients, and non-English-preferring White patients (OR = 1.17, 95% CI = 1.05, 1.30) showed higher odds of being eligible for statins under period-specific guidelines than English-preferring White patients.

Covariate-adjusted odds ratios of meeting statin eligibility for prevention of atherosclerotic cardiovascular events (above), and for having a documented statin prescription in the EHR if eligible (below), 2014–2018. Note: ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; EHR = electronic health record; GEE = generalized estimating equations; PCE = pooled cohort equations. The reference group, English-preferring non-Hispanic White adults, is represented by the vertical dotted line at 1.00 on the x-axis. The dots represent the adjusted odds ratio point estimates and the horizontal lines represent 95% confidence intervals for those estimates. Estimates were derived using GEE logistic regression adjusted for patient's sex, age, insurance status, %federal poverty level, diagnosis of hypertension, obesity, or hyperlipidemia, primary care utilization, and Medicaid expansion State status with clustering on patient's primary clinic. Statin eligible if known ASCVD; or LDL ≥ 190 mg/dL; or diabetes, age 40–75 years, and LDL ≤ 190 mg/dL; or no diabetes, age 40–75 years, and PCE 10-year risk score ≥ 7.5%.

Statin Prescriptions Prior to the ACC/AHA Guideline Change (2009–2013)

Among patients eligible for statins according to guidelines current to the period 2009–2013 (Fig. 1), both English (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 1.06, 1.26) and non-English-preferring Latinos (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.38), English-preferring Black patients (OR = 1.11, 95% CI = 1.02, 1.22), English (OR = 1.26, 95% CI = 1.07, 1.49) and non-English (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.15, 1.44) preferring Asian patients, and White non-English-preferring patients (OR = 1.40, 95% CI = 1.16, 1.68) had increased odds of being prescribed a statin compared to English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites. Non-English Black patients had similar odds (OR = 1.16, 95% CI = 0.88, 1.54) of statin prescription to English-preferring White patients.

Statin Prescriptions after the ACC/AHA Guideline Change (2014–2018)

Among patients eligible for statin therapy according to guidelines current to the period 2014–2018 (Fig. 2), all but two of the race/ethnicity/language groups had higher odds of statin prescribing compared to the reference group of English-speaking White patients (non-English-preferring Latino patients OR = 1.20, 95% CI = 1.15, 1.26; English-preferring Asian patients OR = 1.36, 95% CI = 1.25, 1.48; non-English-preferring Asian patients OR = 1.43, 95% CI = 1.27, 1.61; non-English-preferring White patients OR = 1.18, 95% CI = 1.01, 1.37). Of note, English-preferring Latino patients (OR = 1.01, 95% CI = 0.95, 1.06) and non-English-preferring Black patients (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.98, 1.19) showed similar odds of having a statin prescription as English-preferring White patients while English-preferring Black patients (OR = 0.94, 95% CI = 0.90, 0.98) showed lower odds having a statin prescription on their chart.

DISCUSSION

We performed an analysis of statin eligibility and EHR evidence of statin prescriptions in low-income community health center patients by race, ethnicity, and language preference in two statin guideline eras, separated by the release of the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Treatment of Blood Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk in Adults. Much has been written about these guidelines,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39 but more large-scale evidence of real-world prescribing across race, ethnicity, and language over time in these eras has been needed. Many themes are noteworthy in our analysis, but our initial findings demonstrate two fundamental phenomena: (1) CHCs provide large numbers of statin prescriptions to a diverse population with many statin-eligible patients, but still, (2) a large proportion of eligible patients are not being prescribed a statin. The latter phenomenon should be viewed in the context of the former; delivering care to a large, multiethnic, and low-income population25 has many significant challenges and CHCs should not be singled out for critique in this area, especially as national statin prescribing remains similarly inadequate.40 The possible multifactorial and relative contributions to these patterns—including variable understanding of statin utility and risk among providers, adequate education and communication by providers, patient beliefs, resistance, or access to medications, and the competing priorities of complex patient care in a progressively time-constrained environment for healthcare delivery, and others—still need further work, especially with regards to race/ethnicity and language, and would benefit from further study. Regardless, these findings do underscore the continued need to improve evidence-based cardiovascular risk reduction to the widest possible population, and this task is far from completion. Further equipping CHCs to continue care delivery may accelerate progress towards this end.

Descriptively, overall eligibility did increase in the second period in many groups. While eligibility could have increased because of the increased breadth of criteria contributing to eligibility, these were different patients, and it is possible that unmeasured differences between the patients in each group contributed to these differences. Moreover, the 2013 guidelines’ PCE have been shown to overestimate ASCVD risk across racial and ethnic populations,41,42,43 and this could have contributed to the eligibility findings here.

In the 2009–2013 period, non-English-preferring Latinos were more likely to be eligible for statins than English-preferring Latinos and Whites and more likely to have a statin prescription than English-preferring Whites, while in the 2014–2018 period, both Latino groups were more likely to be eligible for statins, but only non-English-preferring Latino patients were more likely to have a prescription than English-preferring White patients. These findings come in the context of the findings of other racial groups, where non-English-preferring patients are frequently more likely to meet statin eligibility criteria and have a statin prescription on their chart. This increased utilization by non-English-preferring patients may represent a trend noted elsewhere, that patients more likely to be foreign-born (language preference is an oft-used proxy for nativity44,45), and possibly less acculturated46 may be more receptive to care recommendations such as new prescriptions; however, this analysis did not directly measure patient receptivity or adherence. Non-English speaking patients could either be perceived as more “at-risk” by providers, resulting in higher odds of a prescription. In non-US settings, immigrant patients have been shown to utilize antibiotic medications more than native populations,47 but it is uncertain if or why similar associations would manifest in this wholly different clinical arena. Our findings may also add an additional layer to the literature on the “immigrant paradox” phenomenon, whereby immigrants to the US have better outcomes than socioeconomically matched native comparators.48 However, our findings suggest that this paradox may extend to healthcare utilization as well, at least in this setting. This possible phenomenon will also need to be further understood as we seek to build a healthcare system able to care for an increasingly diverse immigrant population, including immigrants in the United States for varying periods of time.

However, while non-English-preferring Latino patients and English-preferring Latinos may both have higher odds than English-preferring Whites prior to the guideline change, a gap between the two groups appeared after the guideline change. In the most recent guideline era, English-preferring Latinos and non-English-preferring Blacks were no longer more likely than English-preferring Whites to have a statin prescription. While much attention is paid to the healthcare access and outcomes for non-English-preferring Latino patients (who may experience language barriers to healthcare access), our analysis demonstrates a deterioration of evidence-based care in non-English-preferring Black patients and English-preferring Latinos over these periods, the latter being a finding noted in other domains in this network. 21,49,50 This finding suggests that increased attention should be paid to the health of both of these groups and the effects of major clinical guidelines on this group’s healthcare and that guidelines may not be sufficient to overcome the systemic racism and barriers that this group may face.

It is notable that in the 2014–2018 time period, English-preferring Black patients were the only group (in either period) to have lower odds of statin prescriptions than English-preferring White patients. This has been noted in smaller populations,51,52 but not in a larger, multistate population in this analysis. While the 2013 guideline change aimed to “Identify groups of patients who will benefit from pharmacological treatment,”8 it seemed to not, in this large, multistate example, result in equitable prescribing in English-preferring Black patients. The evaluation of healthcare equity resulting from clinical guidelines is a pressing priority. Why eligible Black patients were less likely to be prescribed a statin in the context of a major clinical guideline change needs to be better understood. It may be that in the face of structural racism, guideline changes alone may not be enough to overcome healthcare inequities. The PCE tool was the first tool to acknowledge the increased risk of cardiovascular disease in Black patients, 8 and through the guideline, changes may have increased statin eligibility. However, inequities in health care and medication access,51,53,54,55 implicit bias or discrimination,56,57 and/or other racism-related factors,58 all of which have been experienced by Black patients in health care settings for decades,59 may manifest in continued distrust of medical care and continue to hinder access to treatment.

LIMITATIONS

In our analysis, we did not have information on patient medication adherence, declinations, or detailed clinical risk/benefit conversations about the utility, safety, or patient preference in a given clinical scenario or over time if biomarkers or factors change in a given patient. We did not analyze care by provider type/specialty. Next steps should include these elements, to continue to improve our understanding of the gaps in cardiovascular prevention in all populations. Our study population were low-income patients seeking care at community health centers, and may not be representative of care delivered elsewhere or in non-low-income populations. Our sample was limited to adults over 50 years of age, as it was a component of an evaluation of prevention in older adults. However, the inclusion of those aged 40–49 would have resulted in a lower prevalence of eligible patients for stains via PCE criteria after the guideline change, and future work can include or focus on this age group. Our comparison population was low-income English-preferring White patients, who may experience poor health outcomes or experience significant social risks as well. Our relative findings could be different with another comparator population. In this analysis, we did not examine what happened to patients within the 2014–2018 period who already had a prescription in the 2009–2013 period—this time-varying approach is a different research question, is outside the scope of this analysis, and can be the subject of future work.

CONCLUSION

In a real-world analysis of statin eligibility and prescription in thousands of patients, by race, ethnicity, and preferred language, before and after the 2013 ACC/AHA guideline change, we found that while many eligible patients had no evidence of statin prescription, many thousands had these prescriptions documented in community health centers. Within each period, non-English-preferring patients were almost always more likely to be eligible for these prescriptions than English-preferring White patients and to have a statin prescription on their chart. English-preferring Latinos specifically had a less clear utilization advantage as compared to non-English-preferring Latinos, and they, along with English-preferring Blacks were comparatively less likely (than English-preferring non-Hispanic Whites) to have statin prescriptions on their chart after the 2013 guideline change. Our findings highlight the urgent need to evaluate clinical guidelines with respect to real-world healthcare equity and suggest that further work needs to be done to understand the effectiveness of guidelines in all populations and the contextual factors that may impact their utility.

References

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Causes of Death- Hispanic Males- United States 2016 2019 [cited 2022 July 22]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/lcod/men/2016/hispanic/index.htm#anchor_1571145330.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Leading Cause of Death-Hispanics Females 2017 2019 [cited 2021 February 10].

An J, Zhang Y, Muntner P, Moran AE, Hsu JW, Reynolds K. Recurrent Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Event Rates Differ Among Patients Meeting the Very High Risk Definition According to Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity, and Socioeconomic Status. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(23):e017310. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.017310.

Dupre ME, Gu D, Xu H, Willis J, Curtis LH, Peterson ED. Racial and Ethnic Differences in Trajectories of Hospitalization in US Men and Women With Heart Failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(11). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.006290.

Eapen ZJ, Liang L, Shubrook JH, Bauman MA, Bufalino VJ, Bhatt DL, et al. Current quality of cardiovascular prevention for Million Hearts: an analysis of 147,038 outpatients from The Guideline Advantage. Am Heart J. 2014;168(3):398-404. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2014.06.007.

Daviglus ML, Pirzada A, Durazo-Arvizu R, Chen J, Allison M, Avilés-Santa L, et al. Prevalence of Low Cardiovascular Risk Profile Among Diverse Hispanic/Latino Adults in the United States by Age, Sex, and Level of Acculturation: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(8). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.003929.

Casagrande SS, Aviles-Santa L, Corsino L, Daviglus ML, Gallo LC, Espinoza Giacinto RA, et al. Hemoglobin A1C, Blood Pressure, and LDL-Cholesterol Control Among Hispanic/Latino Adults with Diabetes: Results from the Hispanic Community Health Study/study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). Endocr Pract. 2017;23(10):1232-53. https://doi.org/10.4158/EP171765.OR.

Stone NJ, Robinson JG, Lichtenstein AH, Bairey Merz CN, Blum CB, Eckel RH, et al. 2013 ACC/AHA guideline on the treatment of blood cholesterol to reduce atherosclerotic cardiovascular risk in adults: a report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2014;63(25 Pt B):2889-934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2013.11.002.

Adedinsewo D, Taka N, Agasthi P, Sachdeva R, Rust G, Onwuanyi A. Prevalence and Factors Associated With Statin Use Among a Nationally Representative Sample of US Adults: National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2011-2012. Clin Cardiol. 2016;39(9):491-6. https://doi.org/10.1002/clc.22577.

Qato DM, Lee TA, Durazo-Arvizu R, Wu D, Wilder J, Reina SA, et al. Statin and Aspirin Use Among Hispanic and Latino Adults at High Cardiovascular Risk: Findings From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. J Am Heart Assoc. 2016;5(4):e002905. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.115.002905.

Pauff BR, Jiroutek MR, Holland MA, Sutton BS. Statin Prescribing Patterns: An Analysis of Data From Patients With Diabetes in the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Outpatient Department and National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey Databases, 2005-2010. Clin Ther. 2015;37(6):1329-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clinthera.2015.03.020.

Johansen ME, Hefner JL, Foraker RE. Antiplatelet and Statin Use in US Patients With Coronary Artery Disease Categorized by Race/Ethnicity and Gender, 2003 to 2012. Am J Cardiol. 2015;115(11):1507-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjcard.2015.02.052.

Lauffenburger JC, Robinson JG, Oramasionwu C, Fang G. Racial/Ethnic and gender gaps in the use of and adherence to evidence-based preventive therapies among elderly Medicare Part D beneficiaries after acute myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2014;129(7):754-63. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.002658.

Heintzman JD, Bailey SR, Muench J, Killerby M, Cowburn S, Marino M. Lack of Lipid Screening Disparities in Obese Latino Adults at Health Centers. Am J Prev Med. 2017;52(6):805-9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2016.12.020.

Gu A, Kamat S, Argulian E. Trends and disparities in statin use and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels among US patients with diabetes, 1999-2014. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.019.

Jurkowski JM. Nativity and cardiovascular disease screening practices. J Immigr Minor Health. 2006;8(4):339-46. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-006-9004-z.

Guadamuz JS, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Daviglus ML, Perreira KM, Calip GS, Nutescu EA, et al. Immigration Status and Disparities in the Treatment of Cardiovascular Disease Risk Factors in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (Visit 2, 2014-2017). Am J Public Health. 2020;110(9):1397-404. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2020.305745.

Eamranond PP, Wee CC, Legedza AT, Marcantonio ER, Leveille SG. Acculturation and cardiovascular risk factor control among Hispanic adults in the United States. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(6):818-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/003335490912400609.

López-Cevallos DF, Escutia G, González-Peña Y, Garside LI. Cardiovascular disease risk factors among Latino farmworkers in Oregon. Ann Epidemiol. 2019;40:8-12.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.10.002.

Bailey SR, Hwang J, Marino M, Quiñones AR, Lucas JA, Chan BL, et al. Smoking-Cessation Assistance Among Older Adults by Ethnicity/Language Preference. Am J Prev Med. 2022;63(3):423-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2022.03.024.

Heintzman J, Bailey SR, Cowburn S, Dexter E, Carroll J, Marino M. Pneumococcal Vaccination in Low-Income Latinos: An Unexpected Trend in Oregon Community Health Centers. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1733-44. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0159.

Guadamuz JS, Durazo-Arvizu RA, Daviglus ML, Calip GS, Nutescu EA, Qato DM. Statin nonadherence in Latino and noncitizen neighborhoods in New York City, Los Angeles, and Chicago, 2012-2016. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003). 2021;61(4):e263-e78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.japh.2021.01.032.

National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection Ea, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III). Third Report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol in Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) final report. Circulation. 2002;106(25):3143-421.

Qureshi WT, Kaplan RC, Swett K, Burke G, Daviglus M, Jung M, et al. American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Class I Guidelines for the Treatment of Cholesterol to Reduce Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk: Implications for US Hispanics/Latinos Based on Findings From the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos (HCHS/SOL). J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(5). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.116.005045.

National Association of Community Health Centers. Community Health Center Chartbook 2020. 2020. https://www.nachc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/Chartbook-2020-Final.pdf. Accessed 1 Jun 2022.

Kaufmann J, Marino M, Lucas JA, Rodriguez CJ, Bailey SR, April-Sanders AK, et al. Racial, ethnic, and language differences in screening measures for statin therapy following a major guideline change. Prev Med. 2022;164:107338. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2022.107338.

Wójcik C, Shapiro MD. Translating AHA/ACC cholesterol guidelines into meaningful risk reduction. J Fam Pract. 2019;68(4):206;10;12;14;17;21B.

Lowenstern A, Li S, Navar AM, Virani S, Lee LV, Louie MJ, et al. Does clinician-reported lipid guideline adoption translate to guideline-adherent care? An evaluation of the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management (PALM) registry. Am Heart J. 2018;200:118-24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2018.03.011.

Levy ME, Greenberg AE, Magnus M, Younes N, Castel A. Evaluation of Statin Eligibility, Prescribing Practices, and Therapeutic Responses Using ATP III, ACC/AHA, and NLA Dyslipidemia Treatment Guidelines in a Large Urban Cohort of HIV-Infected Outpatients. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2018;32(2):58-69. https://doi.org/10.1089/apc.2017.0304.

Bucheit JD, Helsing H, Nadpara P, Virani SS, Dixon DL. Clinical pharmacist understanding of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guideline. J Clin Lipidol. 2018;12(2):367-74.e3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacl.2017.11.010.

Pagidipati NJ, Navar AM, Mulder H, Sniderman AD, Peterson ED, Pencina MJ. Comparison of Recommended Eligibility for Primary Prevention Statin Therapy Based on the US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendations vs the ACC/AHA Guidelines. JAMA. 2017;317(15):1563-7. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2017.3416.

Hong JC, Blankstein R, Shaw LJ, Padula WV, Arrieta A, Fialkow JA, et al. Implications of Coronary Artery Calcium Testing for Treatment Decisions Among Statin Candidates According to the ACC/AHA Cholesterol Management Guidelines: A Cost-Effectiveness Analysis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(8):938-52. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcmg.2017.04.014.

Phan BAP, Weigel B, Ma Y, Scherzer R, Li D, Hur S, et al. Utility of 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines in HIV-infected adults with carotid atherosclerosis. Circ Cardiovasc Imaging. 2017;10(7). https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.116.005995.

Akhabue E, Rittner SS, Carroll JE, Crawford PM, Dant L, Laws R, et al. Implications of American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association (ACC/AHA) Cholesterol Guidelines on Statin Underutilization for Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease in Diabetes Mellitus Among Several US Networks of Community Health Centers. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6(7). https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.117.005627.

Housholder-Hughes SD, Martin MM, McFarland MR, Creech CJ, Shea MJ. Healthcare provider compliance with the 2013 ACC/AHA Adult Cholesterol Guideline recommendation for high-intensity dose statins for patients with coronary artery disease. Heart Lung. 2017;46(4):328-33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrtlng.2017.03.005.

Pokharel Y, Tang F, Jones PG, Nambi V, Bittner VA, Hira RS, et al. Adoption of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Cholesterol Management Guideline in Cardiology Practices Nationwide. JAMA Cardiol. 2017;2(4):361-9. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamacardio.2016.5922.

Valentino M, Al Danaf J, Panakos A, Ragupathi L, Duffy D, Whellan D. Impact of the 2013 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association cholesterol guidelines on the prescription of high-intensity statins in patients hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome or stroke. Am Heart J. 2016;181:130-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahj.2016.07.024.

Jamé S, Wittenberg E, Potter MB, Fleischmann KE. The new lipid guidelines: what do primary care clinicians think? Am J Med. 2015;128(8):914.e5-.e10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2015.02.013.

Hayward RA. Should family physicians follow the new ACC/AHA cholesterol treatment guideline? Not completely: why it is right to drop LDL-C targets but wrong to recommend statins at a 7.5% 10-year risk. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(4):223-4.

Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, Alonso A, Beaton AZ, Bittencourt MS, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153-e639. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052.

Rana JS, Tabada GH, Solomon MD, Lo JC, Jaffe MG, Sung SH, et al. Accuracy of the Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Risk Equation in a Large Contemporary, Multiethnic Population. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(18):2118-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2016.02.055.

Rodriguez F, Chung S, Blum MR, Coulet A, Basu S, Palaniappan LP. Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk Prediction in Disaggregated Asian and Hispanic Subgroups Using Electronic Health Records. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(14):e011874. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.118.011874.

Muntner P, Colantonio LD, Cushman M, Goff DC, Howard G, Howard VJ, et al. Validation of the atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease Pooled Cohort risk equations. JAMA. 2014;311(14):1406-15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2014.2630.

Arcia E, Skinner M, Bailey D, Correa V. Models of acculturation and health behaviors among Latino immigrants to the US. Soc Sci Med. 2001;53(1):41-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0277-9536(00)00310-5.

Adam MB, McGuire JK, Walsh M, Basta J, LeCroy C. Acculturation as a predictor of the onset of sexual intercourse among Hispanic and white teens. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159(3):261-5. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.159.3.261.

Abraído-Lanza AF, Chao MT, Flórez KR. Do healthy behaviors decline with greater acculturation? Implications for the Latino mortality paradox. Soc Sci Med. 2005;61(6):1243-55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.01.016.

Norris P, Ng LF, Kershaw V, Hanna F, Wong A, Talekar M, et al. Knowledge and reported use of antibiotics amongst immigrant ethnic groups in New Zealand. J Immigr Minor Health. 2010;12(1):107-12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-008-9224-5.

Franzini L, Ribble JC, Keddie AM. Understanding the Hispanic paradox. Ethn Dis. 2001;11(3):496-518.

Heintzman J, Kaufmann J, Lucas J, Suglia S, Garg A, Puro J, et al. Asthma Care Quality, Language, and Ethnicity in a Multi-State Network of Low-Income Children. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(5):707-15. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2020.05.190468.

Heintzman J, Hwang J, Quiñones AR, Guzman CEV, Bailey SR, Lucas J, et al. Influenza and pneumococcal vaccination delivery in older Hispanic populations in the United States. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.17589.

Dorsch MP, Lester CA, Ding Y, Joseph M, Brook RD. Effects of Race on Statin Prescribing for Primary Prevention With High Atherosclerotic Cardiovascular Disease Risk in a Large Healthcare System. J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8(22):e014709. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.119.014709.

Fairman KA, Romanet D, Early NK, Goodlet KJ. Estimated Cardiovascular Risk and Guideline-Concordant Primary Prevention With Statins: Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analyses of US Ambulatory Visits Using Competing Algorithms. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol Ther. 2020;25(1):27-36. https://doi.org/10.1177/1074248419866153.

Flores G, Tomany-Korman SC. Racial and ethnic disparities in medical and dental health, access to care, and use of services in US children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(2):e286-98. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2007-1243.

Ferdinand KC, Yadav K, Nasser SA, Clayton-Jeter HD, Lewin J, Cryer DR, et al. Disparities in hypertension and cardiovascular disease in blacks: The critical role of medication adherence. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2017;19(10):1015-24. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.13089.

Ayanian JZ, Landon BE, Newhouse JP, Zaslavsky AM. Racial and ethnic disparities among enrollees in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(24):2288-97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsa1407273.

Bey GS, Person SD, Kiefe C. Gendered Race and Setting Matter: Sources of Complexity in the Relationships Between Reported Interpersonal Discrimination and Cardiovascular Health in the CARDIA Study. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2020;7(4):687-97. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00699-6.

Saha S, Komaromy M, Koepsell TD, Bindman AB. Patient-physician racial concordance and the perceived quality and use of health care. Arch Intern Med. 1999;159(9):997-1004. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinte.159.9.997.

Forde AT, Sims M, Muntner P, Lewis T, Onwuka A, Moore K, et al. Discrimination and Hypertension Risk Among African Americans in the Jackson Heart Study. Hypertension. 2020;76(3):715-23. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.119.14492.

Reverby SM. The Milbank Memorial Fund and the US Public Health Service Study of Untreated Syphilis in Tuskegee: A Short Historical Reassessment. Milbank Q. 2022;100(2):327-40. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.12574.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute on Aging (Grant number: R01AG056337; Recipient: John Heintzman) and the NIH Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities (Grant Number: R01MD014120; Recipient: John Heintzman).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

This work was conducted with the Accelerating Data Value Across a National Community Health Center Network (ADVANCE) Clinical Research Network (CRN). ADVANCE is a CRN in PCORnet®, the National Patient Centered Outcomes Research Network. ADVANCE is led by OCHIN in partnership with Health Choice Network, Fenway Health, and Oregon Health & Science University. ADVANCE’s participation in PCORnet® is funded through the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI), contract number RI-OCHIN-01-MC.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Heintzman , J., Kaufmann, J., Rodriguez, C.J. et al. Statin Eligibility and Prescribing Across Racial, Ethnic, and Language Groups over the 2013 ACC/AHA Guideline Change: a Retrospective Cohort Analysis from 2009 to 2018. J GEN INTERN MED 38, 2970–2979 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08139-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-023-08139-x