Abstract

This paper examines how integration into various sub-domains of the receiving society, including the labor market, informal contacts, attitudes and values, and identification, is associated with religious change among recent Christian and Muslim immigrants in the Netherlands—one of the least religious countries in Europe. The analysis uses data from the New Immigrants to the Netherlands Survey (NIS2NL), a four-wave panel study of recently arrived immigrants from four countries (Bulgaria, Poland, Spain and Turkey). Using latent growth models, we identify the average trajectory of religious participation (service attendance and prayer) and identity (subjective importance of religion) of recent immigrants and examine the role of time-invariant and time-varying explanations for religious change in the early years of resettlement. We find that immigrants’ religious practices increase in the first years after arrival, following a substantial drop from pre-migration participation levels. However, this increase eventually levels off and even reverses with increasing length of stay. We observe a linear but modest decrease in religious identification over time that replicates across all origin groups. In line with expectations derived from assimilation theory, we find that migrants who are employed and hold more liberal attitudes regarding homosexuality, gender relations, divorce and abortion show a greater decrease in religiosity, whereas the opposite is true for those who identify more strongly with their origin country. The findings are remarkably similar for Muslim and Christian newcomers and suggest that all immigrants are susceptible to the secularizing forces of the receiving society. This indicates the potential for the “bright” boundary between Muslim immigrants and secular hosts to become more “blurred” with increasing length of stay and integration into “the mainstream”.

Zusammenfassung

In diesem Beitrag wird untersucht, wie die Integration in verschiedene Teilbereiche der Aufnahmegesellschaft, darunter der Arbeitsmarkt, informelle Kontakte, Einstellungen und Werte sowie Identifikation, mit dem religiösen Wandel bei christlichen und muslimischen Neuzugewanderten in den Niederlanden – einem der am wenigsten religiösen Länder Europas – zusammenhängt. Die Analyse verwendet Daten aus dem New Immigrants to the Netherlands Survey (NIS2NL), einer Vier-Wellen-Panel-Studie über neu zugewanderte Personen aus vier Ländern (Bulgarien, Polen, Spanien und der Türkei). Mithilfe latenter Wachstumsmodelle ermitteln wir den durchschnittlichen Verlauf der religiösen Partizipation (Gottesdienstbesuch und Gebet) und der religiösen Identität (subjektive Bedeutung der Religion) von Neuzugewanderten und untersuchen die Rolle zeitinvarianter und zeitvariabler Erklärungen für den religiösen Wandel in den ersten Jahren der Neuansiedlung. Wir stellen fest, dass die religiösen Praktiken der Zuwanderer in den ersten Jahren nach ihrer Ankunft zunehmen, nachdem die Teilnahme an den Gottesdiensten direkt nach der Einwanderung stark zurückgegangen ist. Dieser Anstieg flacht jedoch schließlich ab und kehrt sich mit zunehmender Aufenthaltsdauer sogar um. Wir beobachten einen linearen, aber bescheidenen Rückgang der religiösen Identifikation im Laufe der Zeit, der sich über alle Herkunftsgruppen hinweg wiederholt. Im Einklang mit den aus der Assimilationstheorie abgeleiteten Erwartungen stellen wir fest, dass Zugewanderte, die berufstätig sind und eine liberalere Einstellung zu Homosexualität, Geschlechterbeziehungen, Scheidung und Abtreibung haben, eine stärkere Abnahme der Religiosität aufweisen, während das Gegenteil für diejenigen gilt, die sich stärker mit ihrem Herkunftsland identifizieren. Die Ergebnisse sind für muslimische und christliche Neuankömmlinge bemerkenswert ähnlich und legen nahe, dass alle Zugewanderten für die säkularisierenden Kräfte der Aufnahmegesellschaft empfänglich sind. Dies deutet darauf hin, dass die klare Grenze zwischen muslimischen Zugewanderten und säkularen Gastgebern mit zunehmender Aufenthaltsdauer und Integration in den „Mainstream“ immer mehr verschwimmt.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Our contribution to the topic of religion and identity in this Special Issue on Social Integration (Grunow et al., this issue) focusses on individual changes in religiosity among recent immigrants in the Netherlands. Religious identity and practice are central concerns in public and academic debates about immigrants’ integration processes (Brubaker 2015). Particularly in Western Europe, which has steadily secularized over the last decades (Bruce 2011), the relatively high level of religiosity of many immigrants has triggered challenging debates about the role of religion for national identity, “Western” norms and values, and intergroup relations (Norris and Inglehart 2012). The re-emergence of religion as a salient identity in Europe also raises important questions about the governance of religious diversity and the social integration of societies that are increasingly diverse, also in religious terms. From the immigrant perspective, religious communities can be a source of “refuge, respectability and resources” that facilitates their incorporation into the new society (Hirschman 2004). From the majority perspective, and particularly in cases where religious affiliations and levels of religiosity of migrants and their hosts do not align (Foner and Alba 2008), there is a fear that integration of immigrants within their religious communities will create “parallel societies” and hamper social integration beyond religious boundaries. Studying the dynamics of immigrant religiosity, therefore, speaks to potential group-level side-effects of social integration at various levels of inclusiveness.

Analyzing changing religiosity within the context of migration has a long tradition in research on immigrant integration. Early accounts described international migration as a “theologizing experience” (Smith 1978)—though one may question the applicability of this notion to the more fluid and circular contemporary migration streams, particularly within Europe (Engbersen et al. 2013). Qualitative research has carefully described how the meaning of religion adjusts to the new environment after migration (e.g., Cadge and Ecklund 2007) and that religious congregations function as community centers for many newcomers (Warner and Wittner 1998; Ebaugh and Chafetz 2000). However, these accounts by their design tend to overlook the perspective of immigrants who reduce or end their religious involvement in the receiving society. Quantitative studies that examined religious change among more representative samples of immigrants across various receiving countries and origin groups have shown that the event of migration tends to disrupt religious participation (Massey and Higgins 2011; Connor 2008; Diehl and Koenig 2013; Van Tubergen 2013). Yet, these studies were limited to the earliest phase after arrival in which adjustment difficulties accumulate. As a result, longer-term developments are as yet unknown and open questions remain: will immigrants’ piety bounce back and remain stable or grow further over time after the initial turbulent stage directly after resettlement? Or will immigrants’ religiosity steadily adopt to the rather low levels of religious commitment among the majority population? What role does integration into other societal sub-systems, such as the economy, informal networks and sharing core societal values and identities, play in these processes? And are these trends and explanations similar or different for Muslim and Christian immigrants?

In this study, we focus on changes in immigrants’ religiosity in the initial period after migration. Empirically, we examine within- and between-individual differences in three different aspects of religiosity during immigrants’ first years in their new country. We put to the test competing theoretical explanations for increasing, declining or stable religiosity and examine differences between Muslim and Christian newcomers. Conceptually, our approach to social integration incorporates several of the key dimensions outlined in the introductory chapter (Grunow et al., this issue). Our theoretical arguments refer to cooperation within and across religious boundaries as a potential explanation for changes in migrants’ religiosity. We empirically investigate conformity to norms of religious behavior (e.g., weekly mosque or church visits) and relate religiosity to attitudes regarding gender equality and liberal values, which points out the potential for societal consensus vs. dissensus on these issues as a function of migration-related religious diversity and the religious development among recent immigrants.

Using data from a Dutch panel study, the New Immigrants to the Netherlands Survey (NIS2NL; Lubbers et al. 2018), we advance the literature on immigrants’ religiosity in several ways. First, with four waves spanning a total of more than 4 years and additional information about pre-migration religious attendance, the study presents one of the richest accounts of immigrants’ religious development. Second, the detailed information on immigrants’ characteristics prior to migration and the repeated measures of economic, social, cultural, and identity dimensions of integration in the years following migration, allows us to examine a broad set of theoretically derived explanatory factors of immigrants’ changing religiosity simultaneously. Third, the diverse set of religious and origin groups represented in the survey, including Catholics from Poland and Spain, Orthodox Christians from Bulgaria, and Muslims from Turkey and Bulgaria, allows us to compare religious dynamics between Muslim and Christian immigrants, and between those who originate from more religious vs. more secular societies.

Our expectations regarding the association of social integration with religious changes among immigrants are derived from the boundary framework. Therefore, we first elaborate on the notion of religion as a social boundary to explain the relevance of studying religious change among recent immigrants for a comprehensive understanding of social integration in contemporary societies characterized by high levels of religious diversity. Based on the notion that social integration can occur in various domains or societal sub-systems, we specify the characteristics of recent immigrants and their positions in the new country that we expect to go along with enhanced or reduced religiosity, also in light of previous empirical evidence. We additionally ask to what extent religious affiliation may alter the way in which some of these factors influence religious behavior among recent immigrants. Specifically, we consider whether some of the described mechanisms only apply to Christian but not to Muslim immigrants as the latter are confronted with “brighter” boundaries.

2 Theoretical Background

2.1 The Role of Religion for Social Integration: a Boundary Approach

Religion has been a prominent—if not the most prominent—object of study in research on social integration. Durkheim’s (1964 (1893)) notion of social integration reserves an important role for individuals’ participation in religious communities as a constituent of the “social glue”. Both secularization and increasing religious diversity—which can lead to the questioning of the “sacred canopy” (Berger 1969) that is rarer in religiously homogeneous societies—have therefore been discussed extensively as threats to social integration, in scientific as well as public discourses.

The Netherlands, where the current study is situated, is an interesting case in this respect. It has been historically characterized by religious pluralism, including constituent groups of different Protestant factions, a significant minority of Catholics (mostly concentrated in the country’s South) as well as a well-organized subgroup of secular citizens. In the historical Dutch model of “pillarization,” individual citizens led their lives within sub-segments of society defined by bright and all-encompassing religious boundaries. Sharing the same religious affiliation was not only important for the selection of a spouse but also permeated all other spheres of life where nearly all societal institutions (schools, medical care, political parties, media, labor and trade unions, leisure time associations, etc.) were organized and segregated along religious lines. Social integration in the sense of cooperation, consensus and trust within religious groups was strong, but across religious boundaries it was restricted to the elite level in a model of national consensus that would take into account the needs of all (non‑)religious groups while allowing them to lead their life within their co-religious community (Lijphart 1968).

Through the lens of the boundary framework (Lamont and Molnár 2002), which we elaborate below, religion thus historically acted as a bright boundary that separated religious in-group from out-group members without ambiguity and in all spheres of life. This historical legacy contrasts with a high level of secularization in contemporary Dutch society, which has made the distinction between different Christian affiliations and the consequences of individual or family religious background much less important, except for some local communities of fundamentalist Protestants (Kregting et al. 2018). Outside of this “Bible Belt”, religion has lost much of its influence as a social boundary, but the institutional legacy of pillarization has lingered. This has allowed minority religions, such as Islam, to establish a wide range of organizations, including publicly funded schools (Rath et al. 1996). From a comparative European perspective, the accommodation of religious minority rights has been more successful and complete in the Netherlands compared with countries with a stronger bond between the state and a specific Christian religion (Doomernik 1995; Fetzer and Soper 2005). The institutional context in the Netherlands thus affords religious minorities many opportunities to practice their religion and integrate within distinct co-religious communities. At the same time, the country has made a rather radical turn in the political arena, from being one of the forerunners of multiculturalism to placing an increasing emphasis on cultural assimilation (Vasta 2007) and a considerable representation of right-wing parties in parliament who are explicitly mobilizing on anti-Islamic sentiments (Kešić and Duyvendak 2019). As a consequence, Islam acts as a strong symbolic boundary between religious newcomers and the receiving population in contemporary Dutch society. Even though the societal context has thus changed radically from the historical pillarization model, we maintain that conceiving of religion as a social boundary is a useful approach to understanding the dynamics of religiosity among recent immigrants and how they are affected, and in turn contribute to, social integration both at the individual and at the macro level.

Social boundaries are a form of social differentiation, which, on the one hand, is related to unequal access to and distribution of resources and, on the other, to the way in which social interactions between similar individuals are structured (Lamont and Molnár 2002). Group boundaries are the outcome of a two-sided process in which groups define their boundaries in reference to each other. For that purpose, they use a range of different but often overlapping criteria (e.g., linguistic, religious or biological characteristics; Barth 1969; Wimmer 2009). Group boundaries respond to individuals’ need to organize the social world, resulting in the division of the social world into “us” and “them” (Turner et al. 1987). Although the need for social categorization is universal, the characteristics used to define social categories and their boundaries depend strongly on the societal context. Group boundaries can be either symbolic, i.e., relying on ideas about group differences, or social, i.e., emerging from the observation of social interactions between individuals who share specific characteristics. Although distinct in their origins and consequences for subsequent interactions across group boundaries, both types of boundaries contribute to creating a common understanding of the social world and the individual’s place in it (Barth 1969; Lamont and Molnár 2002). Because the characteristics that define a specific social boundary are a function of that boundary rather than being externally given, group boundaries are not fixed and self-evident units of analysis but dynamic constructs that are best examined over time (Barth 1969; Wimmer 2009).

A dynamic approach to social boundaries investigates whether once bright group boundaries become “blurred,” or the other way around, initially unimportant group differences crystallize into mutually exclusive social categories. Where individuals cross boundaries (changing from one social category to another), only the position of the individual but not the content and brightness of the group boundary changes. With regard to religious boundaries, crossing would imply religious conversion, which is quite rare and therefore not included in our analyses, which focus on changes in religious practices and importance over time. When boundaries shift such that previous out-group members are recategorized as members of the in-group, the definition of the in-group is altered, making the previous group distinction more ambiguous and the boundary less bright. The strongest transformation is observed when boundaries are blurred such that the distinction between “us” and “them” becomes less strict and important (Alba 2005; Zolberg and Woon 1999). A blurred boundary thus allows for simultaneous membership in two groups, whereas in the case of a bright boundary, there is no ambiguity about in- and out-group status and interactions between members of these groups are rare (Alba 2005).

Group boundaries are important for research on immigrant integration as the distinction between immigrants and the receiving population is prominent in the early stages after resettlement (Zolberg and Woon 1999). The subsequent period in which immigrants become (more or less successfully) integrated into various sub-systems of the receiving society can accordingly be conceptualized as a form of boundary work in which immigrants and the receiving society (re‑)define group boundaries and membership. The success and form of this integration process varies depending on the content and brightness of the initial boundary (Wimmer 2008; Zolberg and Woon 1999). Where the boundary between newcomers and the receiving society is bright, greater integration into the receiving society should be accompanied by greater cultural similarity.

Considering the high level of secularism in the Netherlands, an alignment to the religiosity of natives would imply religious decline for most immigrants as they become incorporated into the “mainstream,” such that initially bright religious boundaries become increasingly blurred over time. Such boundary blurring between religious groups in conjunction with greater integration of immigrants into all domains of their receiving society would provide support for classic assimilation theory (Gordon 1964) and its contemporary variant (Alba and Nee 2003), expecting immigrants to become more similar to the mainstream in socio-economic as well as socio-cultural terms. An alternative scenario emerges from the same theoretical approach: integration into the local co-ethnic or co-religious community, as a consequence of prevailing investment into ethnic group-specific capital (Esser 2004), would more likely be accompanied by stable or even increasing religiosity, thus emphasizing religious boundaries and brightening them over time. A third alternative is proposed by the theory of segmented assimilation (Zhou 1997), which argues that immigrants’ socio-economic assimilation does not necessarily coincide with increasing cultural similarity. In our case, this would imply that religious changes among immigrants are unrelated to, or decoupled from, integration into the mainstream, such that no noticeable relations exist between immigrants’ level of religious practices and identity and their participation in the economy, contacts with natives, subscription to core societal values and identification with the receiving society.

To empirically examine these three alternative scenarios, we consider different domains of immigrant integration into sub-systems of the receiving society and relate them to changes in three aspects of immigrants’ religiosity. We examine the frequency of service attendance and prayer as public and private aspects of religiosity. This distinction is useful because the first is more affected by opportunity structures (the local availability of houses of worship) as well as being more visible. For migrants who share an affiliation with members of the receiving society, service attendance also provides meeting opportunities beyond the co-ethnic group, which might facilitate the emergence of inter-ethnic contacts and the socio-economic benefits of bridging social capital (Lancee 2010). Thus, for Christian immigrants, service attendance might be positively linked to integration into Dutch society, whereas for Muslim migrants this relation should be less positive given their lower likelihood of acquiring bridging social capital through mosque attendance, and the potential for discrimination that the visible expression of their contested religion implies. The religious practice of service attendance is therefore potentially more important for boundary dynamics between migrants and non-migrants in general, and Muslim migrants in particular, than religious practices that are generally conducted in the privacy of one’s home (prayer) and the subjective importance of religion. We still include these different aspects of religiosity in our research as they might be affected by—and in turn affect—immigrants’ attitudes and values and their willingness to engage in cross-religious social relations. Studying these three aspects of immigrant religion separately (rather than creating a common index denoting religiosity as a general tendency to be involved with religion) allows us to study religious developments in the early phase of resettlement and their relations with integration in an empirically and theoretically more comprehensive manner.

With the same motivation, we consider a broad range of domains of integration and specific indicators. We capture integration into the economy by measuring labor market participation, differentiating the (self‑)employed from the unemployed and economically inactive. By accounting for the frequency of leisure-time contacts with non-migrant Dutch, we assess integration in the realm of social interactions across ethnic boundaries. Relating to the notion of social integration as a form of consensus on important societal values, we examine how attitudes toward gender equality and liberal values (approval of homosexuality, abortion, and divorce) relate to immigrant religiosity. Finally, we consider immigrants’ sense of identification both with the receiving society and with their origin country, and the extent to which they perceive their group to be discriminated against. Whereas labor market participation, contacts with natives, subscription to normative attitudes and values, and identification with the receiving country all reflect a sense of orientation toward the new society or various aspects of becoming part of the “mainstream,” identification with the origin country rather captures an orientation toward the co-ethnic group—which in many cases is also a co-religious community. The perception of unfair treatment of one’s origin group, finally, reflects immigrants’ perceptions of group boundaries as bright and impermeable. Our analysis can therefore shed light on the question whether integration into these specific segments of the receiving society and the perceived brightness of group boundaries is negatively or positively associated with or independent of changes in immigrant religiosity.

Moreover, we examine whether the associations between integration and religious changes differ between Christian and Muslim immigrants. Although ethnicity (i.e., common ancestry) used to be a dominant boundary between immigrants and nonmigrants, with important consequences for national citizenship in Europe (Brubaker 1992), religion has become increasingly important in majority definitions of national in-group membership (Reijerse et al. 2013; Storm 2011) and the religious dimension of immigration is particularly salient in public discourses on diversity (Brubaker 2015). It has been argued that the social and symbolic exclusion of Muslims (more than other religious groups) in European societies blocks the influence of general secularizing forces of the receiving society on Muslim immigrants’ religiosity (Drouhot and Nee 2019; Voas and Fleischmann 2012). This suggests that, first, the trajectory of religious development (increase, decrease or stability) should differ between Muslims and Christians—with more decline among the latter, and prevalent stability or increase among the former—and second, that incorporation into the “mainstream” is more strongly related to religious decline among Muslim than among Christian immigrants.

2.2 Studying Religious Change Among Immigrants in a Secular Destination

Research on religious change among immigrants has been conducted with four distinct approaches. The first compares the levels of religiosity of the foreign-born first generation with their native-born counterparts, i.e., the second generation. The second compares parent–child dyads to study religious transmission within immigrant families. The third focuses on the event of migration and cross-sectionally compares migrants’ religiosity before and after arrival. The fourth observes within-person changes in levels of religiosity over time. Our study combines the third and fourth approaches by observing immigrant religiosity and their integration repeatedly during the first years after resettlement, while accounting for their levels of pre-migration religious participation.

Studying the effect of the migratory event on the religiosity of migrants based on their reports of pre- and post-migration religious participation and identity can shed more light on intra-individual dynamics of religiosity and circumvents the confounds implied in comparing different immigrant generations. Existing studies with such a design show that migration initially lowers the religiosity of both Christian and Muslim newcomers in Europe and is particularly disruptive for public religious practice (Diehl and Koenig 2013; Van Tubergen 2013). However, most previous studies were limited to the first phase after resettlement and hence could not answer the question whether religious participation and identity will bounce back as immigrants settle in, or whether this initial disruption is the first step toward more permanent religious decline. Khoudja (2022) exploited information about a longer time period to carefully unpack religious trends among recent immigrants in the Netherlands. Here, we build on this work and additionally analyze how religious change is associated with the integration of immigrants into their receiving society, thus contributing to the analysis of the role of religious change for the macro-level social integration of religiously diverse societies.

3 Data and Methods

3.1 Data

We use data from the New Immigrant Survey (NIS2L, Lubbers et al. 2018), a panel survey designed to study the early period of recent immigrants’ stay in the Netherlands. Immigrants from Poland, Bulgaria, Turkey, and Spain were followed over four waves, the first of which took place in November 2013 and March 2014, the second in March 2015 and May 2015, the third in September 2016, and the fourth in January 2018. Respondents could complete the questionnaire, which was translated from English into the official language of their origin country, on paper or online.

Among Polish immigrants, a random sample was drawn of persons who had registered in any Dutch municipality for the first time between January 2013 and January 2014. Owing to smaller populations and lower expected response rates this period of first registration was expanded to June 2012 until January 2014 for immigrants from Bulgaria, Spain, and Turkey. In these three origin groups, all new immigrants who registered within this time span were contacted. Initial response rates were 48.4% for Spanish, 31.9% for Polish, 23.1% for Bulgarian, and 28.8% for Turkish respondents with a total response rate of 32.3%. These response rates are not unusual for written surveys among hard-to-reach populations (Stoop 2005) but they imply that the initial sample cannot be considered to be representative of the target population. The sample contained 4808 respondents (1768 Poles, 790 Bulgarians, 921 Turks, and 1329 Spaniards) at the initial wave. Owing to attrition, 2257 respondents remain in Wave 2, 1334 in Wave 3 and 996 in Wave 4.

Even though the survey targeted immigrants who had arrived recently in the Netherlands, some respondents stated that they had already lived in the Netherlands for many years (but apparently only registered recently). As we focus on immigrants’ early period after arrival, we removed observations of respondents who had lived in the Netherlands for more than 36 months at Wave 1 (n = 766) or who did not provide information about their arrival time (n = 441). Furthermore, observations of respondents who provided no information on their religion (n = 81) or who had no religion (n = 757) were also excluded from the analysis mainly because in the case of Bulgarian immigrants, it would not have been clear whether to assign them to the Christian or Muslim group. Robustness checks of our analyses including these respondents in the least religious category of our outcomes did not lead to substantially different results, mainly because they show almost no variation in religiosity over time. Participants with religions other than Christianity or Islam (n = 58) at Wave 1 were also excluded from the analysis. Hence, the analytic sample consists of 2705 respondents at Wave 1, a total of 1301 respondents remain in Wave 2, 785 in Wave 3, and 579 in Wave 4. Comparing the mean/share of our model’s variables in the initial wave between respondents that were present in Wave 1 but not in Wave 4 and respondents who were still present in Wave 4 showed that there were no significant differences in the religiosity variables. However, the former group had a lower share of women (53% vs 59%; p < 0.001), was less likely to be employed (55% vs 60%; p = 0.005), and more likely to be in education (16% vs. 8%; p < 0.001). They also showed less liberal attitudes toward abortion (mdiff = 0.26; p = 0.036) and divorce (mdiff = 0.1; p = 0.021), and had a higher identification with the country of origin (mdiff = 0.11; p = 0.011) and a lower identification with the Netherlands (mdiff = 0.08; p = 0.029). Finally, respondents who were only present in Wave 1 also had a significantly higher level of perceived ethnic discrimination than respondents who still participated in Wave 4 (mdiff = 0.11; p = 0.08).

3.2 Measures

3.2.1 Dependent Variables

We consider three aspects of religiosity that have been measured in each wave. Attendance is measured with the question “Apart from such special occasions as weddings, funerals, etc., about how often do (did) you attend religious worship since (before) moving to the Netherlands?” on a seven-point scale ranging from (1 “more than once a week”, 2 “once a week”, 3 “once a month”, 4 “only on specific holidays”, 5 “once a year”, 6 “less often”, 7 “practically never”). We recode it to a six-point scale by combining the first two categories to have sufficient observations in each category. We also recode the variable so that higher values stand for more frequent attendance.

Praying frequency is measured at each wave with the question “How often did you pray outside of communal prayers since you moved to the Netherlands?” Christians could answer on a six-point scale ranging from 1 “every day” to 6 “never” and Muslims on a seven-point scale from 1 “5 times a day” to 7 “never.” To maximize the number of observations in each category and to have higher values indicating higher praying frequency, we recode this variable for both groups into four categories with 0 “Never or less often than several times a year”, 1 “Several times a year”, 2 “A few times a month,” and 3 “Several times a week or more.”

Subjective religiosity is captured by a latent construct that is based on three items measured in each wave: (1) “My religion is an important part of myself” (importance of religion) and (2) “I have a strong sense of belonging to my religion” (religious belonging) both measured on a five-point scale ranging from 1 “Totally agree” to 5 “Totally disagree,” and (3) “Independently of whether you attend religious group worship or not, how religious would you say you are” (degree of religiosity) measured on a four-point scale from 1 “very religious” to 4 “not religious at all”. The items are recoded so that a higher value indicates higher levels of subjective religiosity. We provide further details on the measurement model of the latent construct below.

3.2.2 Time-Invariant Variables

We include a categorical variable indicating the country of origin distinguishing between Polish, Bulgarian, Turkish, and Spanish immigrants. We also account for highest education received in the origin country and a dummy variable for gender to account for compositional differences between the immigrant groups on these two characteristics, which are known to shape individuals’ religiosity.

Further, pre-migration attendance is measured retrospectively at the first measurement occasion using the same scale as post-migration measurements of attendance. We include this measure as a time-invariant predictor to account for the extent to which individuals’ religiosity in the origin country shapes their religious trajectories in the receiving country. We also have a pre-migration praying frequency measure, but it has a high number of missing values for Christian respondents (n = 965 of overall n = 992 missing values on this variable). We therefore do not include it in the analysis.

3.2.3 Time-Varying Variables

Respondents’ economic activity is measured in each wave and distinguishes between 1 “Employed,” 2 “unemployed,” 3 “In education,” 4 “Homemaker, parental leave, unemployed and not searching for a job,” and 5 “retired, long-term sick, disabled, something else.” The question “How often do you spend time with Dutch people in your free time?” measures social contact with the Dutch with the answer categories 1 “never,” 2 “less often,” 3 “several times a year.”

To measure the effect of liberal-secular attitudes we have a range of attitudinal questions regarding gender relations and sexual orientations that are measured in each wave of the survey. Specifically, we measure on a five-point scale to what extent respondents agree or disagree with the statements “Gay men and lesbians should be free to live their life as they wish” (support homosexuals), “Divorce is usually the best solution when a couple can’t seem to work out their marriage problems” (support divorce), and on a ten-point scale whether abortion can always or never be justified (abortion justified). Finally, we measure agreement or disagreement with the claims “It is more important for men to earn their own income than it is for women,” “Decisions about large purchases are best taken by men,” and “Women should stop working after they have children” on a five-point scale. The latter three items all loaded on a latent factor measuring egalitarian gender attitudes. Measurement invariance across waves is established with strong factorial invariance producing a good model fit (Chi-squared[χ2](df) = 75.141 (42), p = 0.001; root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.017[0,011 0.023]; comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.994; Tucker-Lewis index [TLI] = 0.991; standardized root mean square residual [SRMR] = 0.039).

We measure identification with the origin country using the item “I have a strong sense of belonging to [country of origin],” and identification with the receiving country using the item “I have a strong sense of belonging to the Netherlands” with a five-point scale, with higher values standing for higher levels of identification. Finally, perceived ethnic discrimination is measured with the item “Some say that people from [country of origin] are being discriminated against in the Netherlands. How often do you think [country of origin] people are discriminated against in the Netherlands?” and answers range from 1 “never” to 5 “very often.” Descriptive statistics of all included variables are shown in Table 1.

3.3 Method of Analysis

To describe and explain changes in immigrants’ religiosity over time, we estimate latent growth models (LGMs) using Mplus Version 8.1 (Muthén and Muthén 1998–2017) and the Stata-ado runmplus (Jones 2013) to run Mplus from within Stata/MP 16.1. Applying LGMs to recent immigrants’ religious change allows us to identify the best fitting religious trajectory for the three indicators of religiosity, and to estimate effects of time-invariant and time-varying factors on between- and within-individual differences in religiosity over time. This modeling flexibility is one of the main strengths of LGMs compared with other longitudinal analysis techniques. Furthermore, LGMs provide the possibility of testing for measurement equivalence over time and of incorporating latent constructs in the model.

LGMs are a special form of structural equation modeling applied to longitudinal data (Meredith and Tisak 1990; Bollen and Curran 2006; Preacher et al. 2008). Based on repeated measures γt(t = 1, … ,T), where T indicates the number of waves, they estimate latent growth factors that describe respondents’ average trajectories on the outcome of interest. In a linear latent growth model, there is a (latent) intercept growth factor η0 that represents respondents’ baseline level on the outcome variable at the initial wave, and a linear (latent) slope growth factor η1 that represents the average change over time across individuals. An additional quadradic slope can also be estimated to describe nonlinear growth trajectories. Comparable with random effects in multi-level models, LGMs first estimate intercepts and slopes for each respondent based on the measured outcome representing individuals’ trajectories over time. Then, average intercepts and slopes across individuals are computed, as well as individual deviations from these averages, representing between-individual variation in the growth curve parameters. Hence, a latent growth model operates on two levels with the basic structure consisting of a measurement model at level 1 that looks like this

where γit is the observed measure for case i at time t, η0i the intercept of the trajectory of case i (i.e., the random intercept factor), η1i the slope of the trajectory of case i (i.e., the random slope factor), βt the value of the trend variable for time t, which is fixed to the observed time metric to define the linear or nonlinear trajectory, and εit the disturbances of yit.

The structural model at level 2 looks like this:

where α00 is the mean of the intercepts, α10 the mean of the slopes, ζ0i the individual’s deviation from the population mean, and ζ1 the individual’s deviation from the population slope.

The model described in the equations is called an unconditional linear latent growth model because it just describes the average growth trajectories based on repeated measures without accounting for any predictors. However, LGMs can also be estimated with time-invariant predictors, i.e., variables that are constant in individuals over time (e.g., origin country or pre-migration characteristics), and time-varying predictors, i.e., variables that are measured repeatedly (e.g., our frequency of contact to native Dutch or labor market status).

Time-invariant predictors can be used to explain between-individual differences in the overall growth trajectories (i.e., in the structural model). They can be related to the different latent growth factors as if these would be dependent variables in a regression model. Coefficients of time-invariant factors in conditional latent growth models reflect partial effects net of the other included explanatory factors. The estimated effects of time-invariant coefficients on the intercept of the growth curve are relatively straightforward to interpret. For example, a positive coefficient of pre-migration attendance on the intercept of (post-migration) attendance indicates that respondents who had higher pre-migration levels of attendance have higher levels of attendance at the initial wave. Estimated effects on the slopes are somewhat more complex to interpret because they must be related to the latent slope. If the average growth curve is increasing (indicated by a positive linear slope coefficient), a positive coefficient of pre-migration attendance on the slope implies a steeper increase in attendance for people with higher pre-migration levels of attendance. If the average growth curve is decreasing (indicated by a negative linear slope coefficient), a positive coefficient of pre-migration attendance implies a less strong decrease (or, potentially, no change or an increase) in attendance.

In contrast, time-varying variables can explain within-individual deviations from the average growth curve by predicting the measured outcome in each wave directly (i.e., on the measurement level). Hence, the influence of time-varying predictors may vary over time (though it can also be constrained to be equal). The effects of time-varying predictors on the measured outcomes and the (conditional) latent growth factors are estimated simultaneously, which means that their effects are net of each other. The influence of time-varying factors on the repeated measure should therefore be considered as the “time-specific prediction of the repeated measure after controlling the influence of underlying growth process” (Bollen and Curran 2006, p. 195). This also implies that the estimated latent growth factor coefficient may change when time-varying predictors are included in the model if the latter explain individuals’ deviations from the overall growth trajectory. For example, a negative coefficient of social contact with native Dutch at Wave 1 indicates that contact with native Dutch decreases service attendance in the first wave net of between-individual differences in the intercept and slope of attendance. In Wave 2, the relation between contact and attendance may be allowed to differ (but can also be constrained to be equal as a modeling choice).

To fit the LGM, the loadings of the intercept are fixed to 1 representing the level of religiosity (i.e., attendance, prayer, and subjective religiosity) at the initial measurement. The change in religiosity over time is modeled by additional parameters that use the time passed between each measurement occasions as factor loadings. As the measurement dates differ by a few months between respondents in the first two waves, we use the average time passed to specify the slope(s).Footnote 1 Accordingly, the linear slope loadings are fixed to 0 at Wave 1, 1.25 at Wave 2, 2.66 at Wave 3, and 4 at Wave 4 and the quadradic slope loadings are fixed to the squares of these values. In principle, an infinite number of parameters can be estimated to model change in the outcome, but, in practice, models with more than a linear and a quadradic slope are rarely required conceptually (and often struggle with convergence issues).

Missing data are accounted for by full information maximum likelihood (FIML), which uses all the available information in the specified model to provide a maximum likelihood estimation (see Enders 2001 for more technical details). It has been recommended as one of the most suitable techniques dealing with a high share of missing values in longitudinal data analysis (Graham 2009; Newman 2003; Preacher et al. 2008).

The first step in the analysis is to identify the most appropriate post-migration growth trajectories for our data by estimating increasingly complex unconditional growth models, i.e., models that only estimate growth curves based on the different outcome measures at each time point without any time-invariant or time-varying predictors. We start the analysis of each outcome by estimating an intercept-only model and then stepwise increase model complexity by adding first a linear, and then a quadradic slope. After having identified the best-fitting unconditional growth model (Fig. 1), we include each set of (time-invariant and time-varying) factors derived from the respective integration dimensions described above one-by-one, together with controls for pre-migration attendance, gender, and highest level of education in the origin country (Models 1–4 in Tab. A3–A5 in the Online Appendix). To assess the relative importance of different explanations, we subsequently estimate a model that contains all predictors at once (Model 5 in Tab. A3–A5 in the Online Appendix). Because results did not vary substantially across models, we show the estimates of this complete model as coefficient plots (Figs. 2 and 3) that we produced using the Stata-ado coefplot (Jann 2014). In a final step, we estimate the complete model separately for Christian and Muslim immigrants to assess whether religious dynamics differ between the two groups (Fig. 4).

Trends in religiosity for the whole sample and by religious affiliation. Note: For model identification, the intercept has to be fixed to 0 for categorical and multiple-indicator lateral growth models. Also consider that the scales differ between outcomes (attendance:1–6; praying: 1–4; subjective religiosity: 1–4)

Estimates of time-invariant and latent growth factors with 95% confidence intervals of conditional latent growth models of attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity. Note: (1) No estimates for subjective religiosity owing to the linear shape of the growth curve. The underlying models also account for time-varying factors, whose estimates are shown in Fig. 3 (for the full model, see Tab. A3–A5 in Online Appendix)

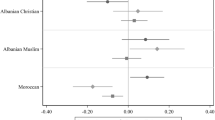

Estimates of time-varying factors with 95% confidence intervals of conditional latent growth models of attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity. Note: The underlying models also account for latent growth and time-invariant factors, whose estimates are shown in Fig. 2 (for the full model, see Tab. A3–A5 in Online Appendix). CO country of origin, RC receiving country

Time varying estimates with 95% confidence intervals of conditional latent growth models of attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity by religious affiliation. Note: The underlying models also account for the time-invariant factors premigration attendance, highest education at arrival in the Netherlands, and gender (full models shown in Tab. A6–A8 of Online Appendix). CO country of origin, RC receiving country

4 Results

4.1 Trends in Religiosity

As attendance and praying frequency are not normally distributed and answer categories are not equally spaced, we use the latent response variable transformation approach to estimate categorical LGMs with a robust weighted least squares estimator and a probit link function to capture changes in immigrants’ religious practice over time. Categorical LGMs assume that there is a continuous latent response variable underlying the categorical observed outcome and basically link the categorical responses to a latent normally distributed continuous variable (see Lee et al. 2018; Masyn et al. 2014). For model identification, the thresholds of attendance and praying are held constant over time and the mean of the intercept factor (i.e., the level of religiosity at Wave 1) is fixed to 0. The mean of the slope and the variance of the intercept and slope growth factors are estimated.

For service attendance, fit statistics of unconditional growth models with varying growth curve specifications (see Tab. A1 in the Online Appendix) show that a quadradic curve (with a linear and quadric slope factor) has the best fit (RMSEA = 0.06; CFI = 0.994; TLI = 0.997; SRMR = 0.016). Even though this model’s Chi-squared value of 95.31 with 10 degrees of freedom is significant, it still has a better overall fit than the model that only includes a linear slope (χ2(df) = 452.03(14); RMSEA = 0.11; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.988; SRMR = 0.032) and the model with only an intercept (χ2(df) = 477,350 (17); RMSEA = 0.1; CFI = 0.969; TLI = 0.989; SRMR = 0.041). Hence, we proceed with the model that specifies a curvilinear trajectory of attendance frequency over time. The results of the unconditional growth model show that attendance frequency increases in the early waves, but this trend flattens and eventually reverses, as illustrated in Fig. 1 (blinear slope = 0.382; z = 16.73; p = 0.00 & bquadratic slope = −0.082; z = −13.77; p = 0.00). The growth factors of this trajectory have significant variance (varintercept = 0.77; p = 0.00; varlinear slope = 0.09, p = 0.00; varquadratic slope = 0.005; p = 0.00) suggesting that there are between-individual differences in the initial level of religiosity as well as in the linear and quadric growth factors.

Figure 1 also shows that the quadradic growth curve of attendance has a somewhat more pronounced reversed U shape for Christian than for Muslim immigrants but ultimately follows a highly similar trajectory. Note that the initial level of religiosity is fixed at 0 and refers to attendance at Wave 1—not to pre-migration attendance. Table 1 shows that there is a substantial drop in attendance between the pre-migration attendance (mean = 2.59) and the first post-migration attendance measure (mean = 1.36). This drop has been well-documented and examined in other studies but is not the focus of this paper, which is mainly interested in the religious trajectories after immigrants arrived in the destination country. The pre-migration measure of attendance will, therefore, only enter as a time-invariant predictor in the conditional latent growth model, which will be discussed below.

For praying frequency, the model with the quadradic slope clearly fits better than the other growth curve specifications (χ2(df) = 6.41 (4), p = 0.17; RMSEA = 0.02, CFI = 1.0; TLI = 1.00; SRMR = 0.01) (see Tab. A1 in the Online Appendix). The trajectory is comparable with religious attendance, with an initial increase indicated by a significantly positive linear slope (blinear slope = 0.092; p = 0.00) and a subsequent flattening and reversal of the curve as indicated by the significantly negative quadradic growth factor (bquadratic slope = −0.025; p = 0.01) that is about a fourth of the size of the linear growth factor (see Fig. 1). The variances of the intercept and the quadradic slope factor are significant (varintercept = 0.92; p = 0.00; varquadratic slope = 0.006; p = 0.03) whereas the linear slope’s variance is not significant (varlinear slope = 0.12; p = 0.30). This suggests that individuals mainly differ in their initial level of religiosity and in the degree to which the increase in praying in the initial phase after migration levels off and reverses. Again, there are no substantial differences between the praying growth curves of Christians and Muslims, although the former seem to have a flatter trajectory.

As we have three measures of subjective religiosity at each time-point, we can calculate a multiple-indicator LGM with a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard errors. In this model specification, the observed indicators are used to estimate latent state variables that are held constant over time. We free covariances between the identical items at consecutive measurement points to account for dependence between error terms, which substantially improves model fit (not shown). The latent state variables are then used to estimate the latent growth curve.

Based on a measurement model with strict invariance over time,Footnote 2 we identify the best-fitting growth curve for subjective religiosity. Comparisons of fit statistics (see Tab. A1 in the appendix) suggests that a model with an intercept and linear growth factor fits the data well (χ2(df) = 386.59(71), p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.041; CFI = 0.971; TLI = 0.973; SRMR = 0.47). A quadratic growth curve for subjective religiosity has a similar fit (χ2(df) = 375.99(67), p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.041; CFI = 0.972; TLI = 0.972; SRMR = 0.44), but, as the variance of the linear and quadradic factor is insignificant in this specification and a visual inspection indicates that the detected curvilinear trend is minimal (not shown), we decided to stick with the more parsimonious linear growth curve specification.

The intercept mean is standardized and centered at 0, so we do not have an estimation of the initial level of subjective religiosity, but the significant variance (varintercept = 1.33; z = 29.78; p < 0.001) indicates that levels of subjective religiosity strongly differ between individuals. The linear slope coefficient of the estimated growth model is significantly negative (blinear slope = −0.06; z = −7.02; p < 0.001) and has a significant variance (varlinear slope = 0.03; z = 4.18; p < 0.001) suggesting that subjective religiosity on average might decrease over time but that the rate of change might differ between individuals. Subjective religiosity seems to decrease at a faster rate among Muslims than among Christians.

4.2 Explaining Changing Religiosity

4.2.1 Between-Individual Differences

Results of the conditional latent growth models of attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity frequency are presented in Figs. 2 and 3 (the more expansive underlying latent growth models are shown in the Online Appendix Tab. A3–A5). As the coefficients mostly point in similar directions for the three dimensions of religiosity, they will be presented jointly. Whenever coefficients diverge substantially across outcomes, we will highlight this in the description of the results.

Figure 2 shows the latent growth curve factors of the complete model and the estimated effects of the time-invariant predictors on the intercept, the linear slope and (for attendance and praying) the quadradic slope. The linear slope of the subjective religiosity growth curve is negative but insignificant, suggesting that our model might explain changes within this religious dimension well. In contrast, the significant linear and quadradic slope of attendance and the significant linear slope of praying indicate that there are unobserved factors that our model does not account for.

There are substantial differences in initial levels of religiosity (as indicated by the intercept) based on pre-migration attendance, gender, and origin country. Unsurprisingly, people with higher pre-migration levels of attendance show higher levels of religiosity at the initial wave across all three outcomes. More interesting are the predictors of the linear slope. Importantly, these coefficients must be interpreted in relation to the average slope. Hence, the negative coefficients of pre-migration attendance on the linear slope of attendance and praying indicate that people with a higher level of attendance in the origin country show a weaker increase in attendance and praying than people who attended less frequently in the origin country. This seemingly counter-intuitive result is explainable insofar as the intercept is already higher for people with high levels of pre-migration attendance, meaning that their rate of change might be lower because they are searching earlier for places of worship and, therefore, already have at an early phase after migration higher attendance and praying levels than people who attended less frequently in the origin country.

There are also substantial gender differences, with women having lower levels of attendance than men at the initial phase after migration but higher levels of praying and subjective religiosity. Furthermore, women have a steeper increase in attendance than men.

Bulgarian and Turkish immigrants show higher levels of attendance and subjective religiosity than Polish immigrants (the reference category) at the initial wave. Turks also show a higher initial praying frequency than Poles. Spanish immigrants have lower attendance levels than Poles but comparable levels of praying and subjective religiosity. The linear increase in attendance and praying over time is less steep for Bulgarians than for Poles. For Spaniards, the linear slope of attendance is more positive than for Poles, indicating a steeper initial increase. The coefficients associated with the quadradic growth factors of attendance and praying show whether the respective time-invariant predictors increase or decrease the bend of the curve. Hence, they also have to be interpreted in relation to the overall negative quadradic slope factors. The positive coefficients of Bulgarians go in the oppositive direction as the overall quadradic slope, indicating that the curvilinear relationship is less pronounced for Bulgarian than for Polish immigrants. Note that these are partial estimated effects net of all other estimated time-invariant and time-varying effects and the average growth curve. This means, for instance, that the similar initial levels of praying and subjective religiosity for Spaniards compared with Poles are conditional on pre-migration attendance (amongst other things). Hence, Spaniards only have similar levels of praying and subjective religiosity to Poles when differences in pre-migration attendance are accounted for.

To sum up the theoretically relevant origin country differences in religious trajectories, while accounting for time-invariant and time-varying factors, Turkish immigrants start from a higher initial level of attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity than Poles but follow similar trajectories over time. For Bulgarians, the growth curves of attendance and praying frequency have a less steep increase and are more linear than quadradic compared with Poles. Spanish immigrants mainly differ in attendance from Poles in that they have lower initial levels of attendance but a steeper increase.

The flatter growth curve of Bulgarian immigrants could be seen as a result of the Christian Orthodox Church not being historically rooted in the Netherlands and most Islamic services having a strong ethnic component tailored to the large Turkish or Moroccan community. As a relatively recent immigrant group, ethno-religious Bulgarian communities are not yet well established in the Netherlands.

4.2.2 Within-Individual Differences

Figure 3 depicts the coefficients of the time-varying predictors for attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity accounting for the average growth curve and the time-invariant predictors shown in Fig. 2. Hence, Figs. 2 and 3 show a different set of results of the same models. In contrast to the time-invariant predictors, the time-varying predictors do not directly influence the overall (latent) growth factors (intercept, slope, and quadradic slope) but are related to the respective wave-specific observed outcome variables. However, as these two components are part of the same equation and estimated simultaneously, the coefficients reflect the estimated effects net of each other. As we do not have any time-specific expectations about the effects of the time-varying variables, we constrained their effects to be equal across waves to simplify interpretation.

Compared with having a job, unemployment in a given wave is associated with higher attendance and subjective religiosity. Not being active in the labor market is related to higher praying and subjective religiosity, and being enrolled in education increases attendance but decreases subjective religiosity. The frequency of contact to native Dutch is not related to any of the three religiosity indicators.

Support for gender equality and liberal values are negatively associated with attendance, praying, and subjective religiosity to varying degrees. Egalitarian gender role attitudes are negatively associated with subjective religiosity and supporting divorce is negatively related to attendance. Supporting abortion and finding homosexuality justified is negatively related to all three religiosity indicators.

Finally, there is a positive relation of identification with the origin country and all three religiosity indicators. Identification with the receiving country is positively associated with attendance but shows no significant association with praying and subjective religiosity. Perceived discrimination against the ethnic ingroup has no significant relationships with religiosity.

4.2.3 Difference by Religious Affiliation

To examine whether dynamics and explanations of religious change differ between Christian and Muslim immigrants, we estimated the complete model separately for these two groups.

As the time-invariant effects are not of main interest here, we only show the latent growth factors and the time-varying coefficients of these models in Fig. 4 (the underlying more expansive models, which also include the coefficients of time-invariant factors, are shown in Tab. A6–A8 in the Online Appendix).

Because the categorical LGMs of praying and attendance that only included Muslims did not converge, we re-estimated the conditional LGMs for Christians and Muslims, treating the outcomes as continuous and using a maximum likelihood estimator with robust standard error. For the Christian group, treating attendance and praying as continuous outcome leads to mostly similar results compared with treating them as ordinal.

The attendance growth curve factors show a similar trajectory (initial increase that levels off and turns into decline) for Muslim and Christian immigrants. Time-varying predictors of attendance are also associated in similar ways for the two groups except for contact with native Dutch, which is positively related to attendance for Christians but not for Muslims. The estimated effect of identification with the receiving country is not significant for the two groups, although it is significantly positive for Christians when estimating the categorical LGM.

The growth curve of praying also follows a similar trajectory for Christians and Muslims though the 95% confidence intervals of the linear and quadradic factors cross zero for Muslims whereas they remain within the positive range for Christians. Further, being unemployed (compared with having a job) is positively related to praying for Christians but not for Muslims.

Comparing dynamics in subjective religiosity between Muslims and Christians shows that the linear growth factor of Christian immigrants is not significant in the complete model whereas it remains significantly negative for Muslims. With respect to the time-varying predictors of subjective religiosity, the coefficients of unemployment and identification with the Netherlands is significantly positive for Christians but not for Muslims.

To sum up, trends and explanations of religious change are strikingly similar between Christians and Muslim immigrants in the Netherlands, with some smaller exceptions (possibly due to differences in sample size).

5 Discussion

5.1 Main Findings

This paper asked how recent immigrants’ religiosity changes in the first years after arrival and what time-invariant and time-varying factors are associated with these changes. Connecting to the main theme of this special issue, we approached these research questions with a boundary framework focusing on how religion as a social boundary may be shaped by integration processes into various subdomains of the receiving society. We argued that owing to the high levels of secularism in the Netherlands, decreasing religiosity among immigrants linked to greater incorporation into the mainstream, which we studied using micro-level data, could be viewed as providing the potential for a blurring of religious boundaries at the macro-level, whereas the opposite relation between religiosity and involvement in the co-ethnic community would suggest a brightening of religious boundaries over time. From this point of view, we examined to what extent integration into various subdomains of society (economic participation, social relations, norms and values, and identification) is accompanied by increases or decreases in recent immigrants’ religiosity. In addition, building on research that highlighted the bright religious boundaries that Muslims are confronted with in Western European societies, we asked whether religious adaptation processes into the receiving society look differently for Muslims than for Christians.

Overall, our findings show rather consistently that greater integration into the societal mainstream in the form of economic participation and adherence to dominant liberal-egalitarian attitudes about gender relations, homosexuality, abortion, and divorce is accompanied by a decline in religiosity among recent immigrants, which lends strong support for the expectations formulated by new assimilation theory (Alba and Nee 2003). In contrast, we find little evidence for a decoupling of structural and cultural integration as predicted by segmented assimilation theory (Zhou 1997).

A rather unexpected finding in this context is that greater identification with the receiving country was related to an increase in religiosity over time (in terms of attendance and subjective importance), even though the highly secular norms seemingly dominant in the Netherlands would lead us to expect an inverse relationship between identification with the receiving country and religiosity (also see Fleischmann and Phalet 2018). However, this relation was rather driven by Christian and less by Muslim immigrants, which indicates that being Christian and identifying with the Netherlands can go hand in hand, whereas there is no such corresponding meaningful relation between Islamic religiosity and identification with the Netherlands. This suggests that despite the currently high levels of nonreligiousness in the Netherlands (Kregting et al. 2018), the rootedness of the Dutch national identity in Christianity, as reflected by the pillar system that provides Protestants as well as Catholics with highly symbolic and institutional links with the nation, provides Christian newcomers with the opportunity to follow their faith and consider themselves as part of the Dutch mainstream, even though the majority of the native Dutch population is considered nonreligious nowadays. For Muslim immigrants, however, the bright religious boundaries separating them from the societal mainstream make such links impossible.

In contrast to the association of integration into the societal mainstream of the Netherlands with secularization or religious decline, identification with the country of origin was associated with increasing subjective religiosity for both Muslims and Christians. Based on this pattern, the country of origin can be viewed as a source of disintegration and fears of “parallel societies” may not be entirely ungrounded.

But the overall trend is that even though religious practices bounce back after the initial disruption caused by the event of migration, they eventually decline again. Moreover, subjective religiosity shows a steady decrease over time. So, although religiosity is affected in different directions through immigrants’ integration into the mainstream vs. their co-ethnic communities, the balance weighs in on the mainstream, as immigrants become less religious over time and, therefore, more like the secular majority population. As this is also accompanied by greater integration into other subsystems of society, our findings suggest that religious boundaries at the macro-level potentially become less salient over time, based on the decreasing religiosity that we identified at the micro-level. This interpretation is also corroborated by the largely absent relation between perceived ethnic discrimination and religiosity. A consistent negative relation between perceived discrimination and religiosity would be viewed in the literature as a strong indicator for salient exclusion processes associated with bright symbolic boundaries (Diehl and Koenig 2009). The absence of such associations indicates that at least among recent immigrants in the Netherlands, there is no tendency for a “reactive religiosity” with roots in exclusion experiences in the receiving society. Instead, the strongest sources of recent immigrants’ religiosity seem to be located in remaining connections to their country of origin and social ties to their co-ethnic community.

As our main findings hold for Muslim as well as Christian immigrants both in terms of trends as well as relations with integration in other domains, we can, surprisingly, conclude that Muslim religiosity does not stand out but is subject to the same secularizing forces as other religions (see Voas and Fleischmann 2012), at least in the context of one of the most secular receiving societies in Western Europe.

5.2 Limitations and Suggestions for Future Research

Of course, our study is not without limitations. First, despite the longitudinal data at hand, we make no strong claims about causality: whether changes in religiosity or integration into various domains of the receiving society comes first is not a question we can answer based on our analysis. However, estimating LGMs allowed us to include time-invariant as well time-varying predictors so that we could describe the average growth trajectories of recent immigrants’ religiosity net of other integration processes and accounting for pre-migration attendance. Hence, we do improve on previous research by showing that religious change among recent immigrants is not a mere result of selection effects (with more religious individuals disproportionally returning to the country of origin), but that individuals do in fact change the strength of their religious participation and identification in the initial years after migration, and that these within-individual changes are related to immigrants’ experiences during the integration process in the direction largely predicted by neo-assimilation theory.

Our sample of recent immigrants is primarily young and highly educated, and they originate from urban areas. This is reflective of contemporary migration but different from historical migration streams of post-colonial and labor migrants. Therefore, our results should not be generalized to groups and time periods with different migration histories and contexts of reception. Furthermore, owing to the high levels of attrition the findings may not be generalizable to the entire population of all recent immigrants in the Netherlands from the sampled origin groups either. Even though those who remained until Wave 4 did not differ substantially in their levels of religiosity in the initial wave from those who dropped out, they had somewhat more liberal attitudes, identified less with the origin country and more with the Netherlands, and perceived less ethnic discrimination. This could mean that those who remained in the sample may have been somewhat more open for the secularizing forces of the Netherlands than those who left. However, immigrants who leave the Netherlands after a relatively short stay are also not the central actors in the long-term boundary-making processes. Strictly speaking, only those immigrants who remain in the receiving country for a longer time are relevant objects of study for the social integration of the receiving society.

There remains much to do for future research: Ideally, we would need even longer time periods, other destination countries, and larger samples to split up religious groups further and conduct separate analyses by origin country. But as it is extremely costly to reach recent immigrants and follow them over time, it is unlikely that better data will become available any time soon. Nonetheless, the reversal of initial trends in religiosity and their association with integration into the mainstream, which we have observed in this study, documents the importance of analyzing the dynamics of immigrant religiosity and considering more than the initial stage after resettlement.

5.3 Conclusion

We can conclude that, indeed, religion functions as a social boundary and that fitting in with the mainstream is accompanied with decreasing religiosity. These associations provide the potential for the blurring of initially bright social boundaries between religious groups within society—or perhaps decreasing individual-level religiosity can be considered as an aspect of boundary blurring in the integration process. This is up for debate as we cannot draw conclusions about causal order based on our models and data considering that both integration into the receiving society and religiosity are dynamic and undergo many changes in the early years after resettlement that we observed.

The overall trends can be interpreted as follows: religious participation recovers from the initial “shock” of migration but decreases in the long run, and this is more pronounced for attendance than for praying frequency, which remains rather stable among Christian immigrants, but follows a clear curvilinear trajectory among Muslims. For subjective importance, we observe no corresponding increase after migration but rather a steady linear decline with longer stay in the Netherlands. We find no evidence for a long-term increase or stability in religiosity, but, overall, there is more evidence for declining religiosity along with greater integration of immigrants into various subsystems of their new society.

In sum, religious boundaries that separate newcomers from the highly secularized Dutch mainstream are bright at the start of the process, particularly among Muslims, but seem to become increasingly blurred over time. This implies that the role of religion for social integration is limited: it neither hampers the integration of new arrivals into various subsystems of the new society, nor do initial differences in religious affiliation and levels of religiosity crystallize into bright and stable boundaries between different religious groups. Despite the formidable challenges it poses in the early stages of the arrival of new religious minorities, migration-related religious diversity, therefore, does not seem to pose a long-term risk to the social integration of receiving societies in terms of cooperation across boundaries, consensus between different subgroups of the population, or for maintaining a well-functioning social order.

Notes

At Wave 2, respondents could have been observed for four different time periods: 12 months (if t1 = March 2014 and t2 = March 2015), 14 months (t1 = March 2014 and t2 = May 2015), 16 months (t1 = November 2013 and t2 = March 2015), 18 months (t1 = November 2013 and t2 = May 2015). Hence, 15 months or 1.25 years on average. At Wave 3, which took place in September 2016, respondents with t1 = March 2014 were observed for 30 months and respondent with t1 = November 2013 for 34 months. Hence, 32 months or 2.66 years on average. Wave 4: 46 months or 50 months = 48 months or 4 years on average.

The main advantage of multiple-indicator compared with single-indicator LGMs is that they allow testing for measurement invariance and reduce measurement bias. Establishing measurement invariance is important to make sure that observed changes in subjective religiosity are not due to changing meanings of the construct over time (i.e., changing relations between the indicators and the latent construct). We test this by estimating a measurement model of the latent variable subjective religiosity at the four different time-points using the three indicators without assuming any kind of relation between the latent factors. We then introduce varying degrees of constraints to the model to identify the strictest possible specification with acceptable overall model fit. To specify multiple indicator latent growth models, at least strong factorial invariance is required, which means that factor loadings and intercepts of the latent factor are invariant over time (Geiser 2011). The estimated models with strong (equal loadings, intercepts) factorial invariance and strict factorial invariance (equal loadings, intercepts, and error variance) both show a similar fit (see Tab. A2 in the appendix). We decide to stick with the strict factorial invariance specification (χ2(df) = 368, 24(66), p < 0.001; RMSEA = 0.04; CFI = 0.97; TLI = 0.97; SRMR = 0.4) to estimate a more parsimonious model.

References

Alba, Richard. 2005. Bright vs. Blurred Boundaries: Second-Generation Assimilation and Exclusion in France, Germany, and the United States. Ethnic and Racial Studies 28(1):20–49.

Alba, Richard, and Victor Nee. 2003. Remaking the American Mainstream: Assimilation and Contemporary Immigration. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Barth, Fredrik. 1969. Ethnic Groups and Boundaries : The Social Organization of Culture Difference, ed. Fredrik Barth. Reissued. Long Grove, Ill.: Waveland Press.

Berger, Peter L. 1969. The Sacred Canopy: Elements of a Sociological Theory of Religion. Garden City, N. Y.: Doubleday.

Bollen, Kenneth A., and Patrick J. Curran. 2006. Latent Curve Models: A Structural Equation Perspective. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley.

Brubaker, Rogers. 1992. Citizenship and nationhood in France and Germany. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Brubaker, Rogers. 2015. Grounds for Difference. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bruce, Steve. 2011. Secularization. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cadge, Wendy, and Elaine Howard Ecklund. 2007. Immigration and Religion. Annual Review of Sociology 33(1):359–79.

Connor, Phillip. 2008. Increase or Decrease? The Impact of the International Migratory Event on Immigrant Religious Participation. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion 4 (2):243–57.

Diehl, Claudia, and Matthias Koenig. 2009. Religiosität türkischer Migranten im Generationenverlauf: Ein Befund und einige Erklärungsversuche. Zeitschrift Für Soziologie 38(4):300–319.

Diehl, Claudia, and Matthias Koenig. 2013. Zwischen Säkularisierung und religiöser Reorganisation – Eine Analyse der Religiosität türkischer und polnischer Neuzuwanderer in Deutschland. In Religion und Gesellschaft - Aktuelle Perspektiven. Kölner Zeitschrift für Soziologie und Sozialpsychologie (Suppl 1) (= Special Issue 53), eds. Matthias Koenig and Christof Wolf, 235–258. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Doomernik, Jeroen. 1995. The Institutionalization of Turkish Islam in Germany and The Netherlands: A Comparison. Ethnic and Racial Studies 18(1):46–63.