Abstract

Does Chinese development assistance undermine recipient country compliance with DAC aid conditionality? I theorize that Chinese aid provides an outside option that weakens recipient countries’ incentives to comply with conditionality by decreasing their dependence on DAC donors and undermining the ability of DAC donors to credibly commit to the enforcement of aid agreements. I test the theoretical predictions using project-level data on government compliance with World Bank project agreements for a sample of 42 Sub-Saharan African countries from 2000-2014. The empirical analysis finds strong support for the hypothesis that Chinese development assistance decreases the likelihood of recipient country compliance with the conditions specified in World Bank project agreements. The results are robust to alternative measures of Chinese development assistance, potential sources of omitted variable bias, and an instrumental variable estimation strategy.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The DAC is an international forum of 30 Western donor agencies that was created to discuss and promote cooperation on issues surrounding development assistance practices in developing countries.

This article defines Chinese development assistance using the broader definition of official finance which captures both official development assistance and other official finance. Throughout this article, the terms “development assistance” and “aid” are used interchangeably when referring to Chinese official finance.

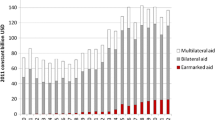

United States commitments of official finance to Sub-Saharan Africa totaled $106 billion (2016 USD) from 2000-2014. Despite being the same relative size, China and the United States have very different development finance portfolios. The United States’ portfolio is almost entirely comprised of ODA.

Swaziland is currently the only remaining African nation to recognize Taiwan.

A subset of projects in the dataset receive ratings from Implementation Completion Reports and more in-depth Project Performance Assessment Reports. If projects were evaluated multiple times for government performance, I selected the most recent evaluation rating.

Supplementary material for this article is available on the website of the Review of International Organizations.

Girod and Tobin (2016), 221.

Data on the number of conditions attached to World Bank projects is only available for the subset of Development Finance Policy projects.

ODA is defined by the DAC as flows of official financing that are administered to promote the economic development and welfare of developing countries that are concessional with a grant element of at least 25 percent.

Examples of OOF include loans with a development intent with a grant element lower than 25 percent, grants with a representational purpose, and export financing.

The use of an alternative three-year average prior to project completion does not substantively change the findings.

Debt service/GNI is also employed in robustness checks to address concerns of multicollinearity.

Political corruption is defined as the frequency in which members of the government: 1) grant favors in exchange for bribes and 2) steal, embezzle, or misappropriate state resources for personal use.

Average semi-elasticities were calculated using the aextlogit Stata module. Regression results that report the coefficients as the change in log odds are also provided in Appendix Table B1. Results from an alternative linear probability model (LPM) are also reported in the ??.

Robustness checks include the full set of project sectors.

The results are not substantively changed if the two measures are included in separate regressions.

The inclusion of Chinese FDI inflows to recipient countries limits the study period to 2008-2012.

Corresponding regression results are presented in Appendix Table B7.

An alternative IV analysis using the primary project-level dataset is reported in the ??

In contrast to most Bartik-style instruments, where cross-sectional units vary along several dimensions, the units in this approach only differ along one dimension- the probability to receive Chinese aid.

The classification is based on the median probability of receiving Chinese official finance during the study period. Plots are reported in Appendix Figure B3.

IV robustness tests are reported in Appendix Table B8.

Table 2 Instrumental variable estimation results

References

Bailey, M.A., Strezhnev, A., & Voeten, E. (2017). Estimating dynamic state preferences from United Nations voting data. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 61(2), 430–456.

Baum, C.F., Schaffer, M.E., & Stillman, S. (2007). Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. The Stata Journal, 7(4), 465–506.

Bermeo, S.B. (2016). Aid is not oil: Donor utility, heterogeneous aid, and the aid-democratization relationship. International Organization, 70(1), 1–32.

Bräutigam, D. (2009). The dragon’s gift: The real story of China in Africa. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bräutigam, D. (2011). Aid with Chinese characteristics: Chinese foreign aid and development finance meet the OECD-DAC aid regime. Journal of International Development, 23(5), 752–764.

Brazys, S., Elkink, J.A., & Kelly, G. (2017). Bad neighbors? How co-located Chinese and World Bank development projects impact local corruption in Tanzania. The Review of International Organizations, 12(2), 227–253.

Brazys, S., & Vadlamannati, K.C. (2020). Aid curse with Chinese characteristics? Chinese development flows and economic reforms. Public Choice, 1–24.

Bueno De Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2007). Foreign aid and policy concessions. Journal of Conflict Resolution, 51(2), 251–284.

Bueno De Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2009). A political economy of aid. International Organization, 63(02), 309–340.

Christian, P. (2017). Revisiting the effect of food aid on conflict :A methodological caution. Washington: The World Bank.

Chun, Z. (2014). China-Zimbabwe relations: A model of China-Africa relations? South African Institute of International Affairs Occasional Paper 205.

Coppedge, M., et al. (2017). V-Dem Country-Year/Country-Date Dataset v7.1.

Corkin, L. (2011). Uneasy allies: China’s evolving relations with Angola. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 29(2), 169–180.

Cruz, C., Keefer, P., & Scartascini, C. (2018). Database of Political Institutions 2017 (DPI2017). Inter-American Development Bank. Numbers for Development. https://mydata.iadb.org/Reform-Modernization-of-the-State/Database-of-Political-Institutions-2017/938i-s2bwhttps://mydata.iadb.org/Reform-Modernization-of-the-State/Database-of-Political-Institutions-2017/938i-s2bw.

Denizer, C., Kaufmann, D., & Kraay, A. (2013). Good countries or good projects? Macro and micro correlates of World Bank project performance. Journal of Development Economics, 105, 288– 302.

Dollar, D., & Svensson, J. (2000). What explains the success or failure of structural adjustment programmes? The Economic Journal, 110(466), 894–917.

Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Hodler, R., Parks, B.C., Raschky, P.A., & Tierney, M.J. (2019). African leaders and the geography of China’s foreign assistance. Journal of Development Economics, 140, 44–71.

Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B., Strange, A., & Tierney, M.J. (2021). Aid, China, and growth: Evidence from a new global development finance dataset. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13(2), 135–174.

Dreher, A., Fuchs, A., Parks, B., Strange, A.M., & Tierney, M.J. (2018). Apples and dragon fruits: The determinants of aid and other forms of state financing from China to Africa. International Studies Quarterly, 62(1), 182–194.

Dreher, A., Sturm, J.-E., & Vreeland, J.R. (2009). Development aid and international politics: Does membership on the UN Security Council influence World Bank decisions? Journal of Development Economics, 88(1), 1–18.

Dreher, A., & Vaubel, R. (2004). The causes and consequences of IMF conditionality. Emerging Markets Finance and Trade, 40(3), 26–54.

Dunning, T. (2004). Conditioning the effects of aid: Cold War politics, donor credibility, and democracy in Africa. International Organization, 58(2), 409–423.

Girod, D. (2018). The political economy of aid conditionality. In Oxford research encyclopedia of politics.

Girod, D.M., & Tobin, J.L. (2016). Take the money and run: The determinants of compliance with aid agreements. International Organization, 70(01), 209–239.

Goldsmith-Pinkham, P., Sorkin, I., & Swift, H. (2020). Bartik instruments: what, when, why, and how. American Economic Review, 110(8), 2586–2624.

Greenhill, R., Prizzon, A., & Rogerson, A. (2016). The age of choice: Developing countries in the new aid landscape. In The fragmentation of aid (pp. 137–151). Springer.

Henisz, W.J. (2000). The institutional environment for economic growth. Economics & Politics, 12(1), 1–31.

Hernandez, D. (2017). Are new donors challenging World Bank conditionality? World Development, 96, 529–549.

Humphrey, C., & Michaelowa, K. (2019). China in Africa: Competition for traditional development finance institutions? World Development, 120, 15–28.

IEG. (2015). World bank project performance ratings codebook. https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/sites/default/files/Data/reports/ieg-wb-project-performance-ratings-codebook_092015.pdf.

IEG. (2017). World bank project performance ratings. https://ieg.worldbankgroup.org/data.

Isaksson, A.-S., & Kotsadam, A. (2018). Chinese aid and local corruption. Journal of Public Economics, 159, 146–159.

Ivanova, A., Mayer, W., Mourmouras, A., & Anayiotos, G. (2001). What determines the success or failure of Fund-supported programs? IMF Working Paper.

Joyce, J.P. (2006). Promises made, promises broken: a model of IMF program implementation. Economics & Politics, 18(3), 339–365.

Kilama, E.G. (2016). Evidences on donors competition in Africa: Traditional donors versus China. Journal of International Development, 28(4), 528–551.

Kilby, C. (2009). The political economy of conditionality: An empirical analysis of World Bank loan disbursements. Journal of Development Economics, 89(1), 51–61.

Kilby, C. (2015). Assessing the impact of World Bank preparation on project outcomes. Journal of Development Economics, 115, 111–123.

Kjøllesdal, K., & Welle-Strand, A. (2010). Foreign aid strategy: China taking over? Asian Social Science, 6(10).

Kynge, J. (2014). Uganda turns east: Chinese money will build infrastructure says Museveni. https://www.ft.com/content/ab12d8da-5936-11e4-9546-00144feab7de.

Li, X. (2017). Does conditionality still work? China’s development assistance and democracy in Africa. Chinese Political Science Review, 2(2), 201–220.

Marshall, M.G., Jaggers, K., & Gurr, T.R. (2002). Polity IV project. Center for International Development and Conflict Management at the University of Maryland College Park.

Martens, B., Mummert, U., Murrell, P., & Seabright, P. (2002). The institutional economics of foreign aid. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Mesquita, B., & Smith, A. (2016). Bueno de Competition and collaboration in aid-for-policy deals. International Studies Quarterly, 60(3), 413–426.

Montinola, G.R. (2010). When does aid conditionality work? Studies in Comparative International Development, 45(3), 358–382.

New Vision. (2018). China is our true friend, says Museveni. https://www.newvision.co.ug/new_vision/news/1479618/china-true-friend-museveni.

Nunn, N., & Qian, N. (2014). Us food aid and civil conflict. American Economic Review, 104(6), 1630–66.

OECD. (2018a). Development finance of countries beyond the DAC. http://www.oecd.org/dac/stats/non-dac-reporting.htm.

OECD. (2018b). Query wizard for international development statistics. https://stats.oecd.org/qwids/.

Pettersson, T., & Wallensteen, P. (2015). Armed conflicts, 1946–2014. Journal of Peace Research, 52(4), 536–550.

Santos Silva, J. (2016). AEXTLOGIT: Stata module to compute average elasticities for fixed effects logit.

Smets, L., Knack, S., & Molenaers, N. (2013). Political ideology, quality at entry and the success of economic reform programs. The Review of International Organizations, 8(4), 447–476.

Staiger, D., & Stock, J.H. (1997). Instrumental variables regression with weak instruments. Econometrica, 557–586.

State Council PRC. (2011). Chinese foreign aid white paper. http://www.gov.cn/english/official/2011-04/21/content_1849913.htm.

Stone, R.W. (2004). The political economy of IMF lending in Africa. American Political Science Review, 98(04), 577–591.

Strange, A.M., Cheng, M., Russell, B., Ghose, S., & Parks, B. (2017). Aiddata’s Tracking Underreported Financial Flows (TUFF) Methodology, Version 1.3 Williamsburg, VA, AidData at William & Mary.

Swedlund, H.J. (2017a). Can foreign aid donors credibly threaten to suspend aid? Evidence from a cross-national survey of donor officials. Review of International Political Economy, 24(3), 454–496.

Swedlund, H.J. (2017b). The development dance: How donors and recipients negotiate the delivery of foreign aid. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Swedlund, H.J. (2017c). Is China eroding the bargaining power of traditional donors in Africa? International Affairs, 93(2), 389–408.

The Telegraph. (2014). Uganda tells West it can ’keep its aid’ after anti-gay law criticism. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/uganda/10664588/Uganda-tells-West-it-can-keep-its-aid-after-anti-gay-law-criticism.htmlhttps://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/uganda/10664588/Uganda-tells-West-it-can-keep-its-aid-after-anti-gay-law-criticism.htmlhttps://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/africaandindianocean/uganda/10664588/Uganda-tells-West-it-can-keep-its-aid-after-anti-gay-law-criticism.html.

UNCTAD. (2014). Bilateral FDI Statistics. http://unctad.org/Sections/dite_fdistat/docs/webdiaeia2014d3_CHN.pdf.

Vadlamannati, K.C., Li, Y., Brazys, S.R., & Dukalskis, A. (2019). Building bridges or breaking bonds? The Belt and Road Initiative and foreign aid competition. AidData Working Paper 72 Williamsburg, VA, AidData at William & Mary.

Vreeland, J.R. (2006). The International Monetary Fund (IMF): politics of conditional lending, Routledge, Abingdon.

WITS. (2017). World integrated trade solutions. https://wits.worldbank.org.

Woods, N. (2008). Whose aid? Whose influence? China, emerging donors and the silent revolution in development assistance. International Affairs, 84 (6), 1205–1221.

Wright, J. (2008). To invest or insure? How authoritarian time horizons impact foreign aid effectiveness. Comparative Political Studies, 41(7), 971–1000.

Zeitz, A.O. (2021). Emulate or differentiate? Chinese development finance, competition, and World Bank infrastructure funding. The Review of International Organizations, 16(2), 265–292.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editor and three anonymous referees for helpful suggestions. I am especially grateful to Layna Mosley, Lucy Martin, and Cameron Ballard-Rosa for their valuable feedback at different stages of the project. I also thank participants from the Tracking International Aid and Investment from Emerging Economies (Heidelberg 2017) and IO Conditionality (IBEI 2019) workshops. Any errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Responsible editor: Axel Dreher

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Watkins, M. Undermining conditionality? The effect of Chinese development assistance on compliance with World Bank project agreements. Rev Int Organ 17, 667–690 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09443-z

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-021-09443-z