Abstract

Cross-linguistically, morphomes are empirically robust but there are few well-studied cases outside of Romance. We analyze the distribution of present and aorist stems in Western Armenian, an understudied Indo-European language. Canonically, the aorist encodes perfective aspect, but it is meaninglessly used in different paradigm cells for different conjugation classes. For these meaningless cases, the aorist stem acts as a morphomic item. The shape of the aorist stem varies across conjugation classes, including regular classes that use a dedicated aorist suffix vs. irregular classes that use root suppletion. This parallelism across the regular and irregular verbs further establishes that the aorist stem is a legitimate morphological item, and not just a set of homophonous items. We formalize the data in Distributed Morphology, a post-syntactic morphological framework. We use head-insertion or node-sprouting to model how the aorist suffix has canonical perfective semantics, but it is meaninglessly inserted by the morphology in non-perfective contexts. We find that the creation of the aorist stem occurs early in the derivation, and it cyclically interacts with allomorphy and morphophonological alternations. In sum, the morphomic aorist is well-integrated into Armenian morphotactics, and morphomic elements interact with other morphological operations.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

For discussion, we thank Mark Aronoff and Borja Herce. Our gratitude to the editor (Olivier Bonami) and the reviewers for bearing with us.

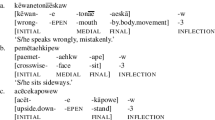

Data is from our native judgments, corroborated with extensive paradigms that can be found in Boyacioglu (2010), and accessible online from Boyacioglu and Dolatian (2020). A general analysis of the conjugation system of Armenian can be found in Dolatian and Guekguezian (2021). Our glossing uses the Leipzig glosses with the following additions: aor (aorist), cn (connegative), eptcp (evidential participle), inch (inchoative), lv (linking vowel), ptcp (participle), t (tense), th (theme), rptcp (resultative participle), sptcp (subject participle), vx (meaningless infix/suffix). Data is in IPA based on the phonology of Lebanon/US-based Western Armenian where affricates are unaspirated. When useful, glosses are placed in text with brackets. Supplementary materials are in https://osf.io/496d3/.

The present stem is also call the infinitive stem (Dum-Tragut, 2009; 199). The aorist stem is also called the preterite (Fairbanks, 1958; 152). Other names that we’ve seldom encountered are imperfective vs. perfective, and present vs. past. The Armenian name for the aorist stem is also just the past perfective stem, and it can be further subcategorized as [t͡sojɑɡɑn himkʰ] ‘stem with the t͡s sound’ (as used for regular verbs) vs [ɑnt͡sojɑɡɑn himkʰ] ‘stem without the t͡s sound’ (as used for irregulars) (

, 1962; 328).

, 1962; 328).Some grammars treat the present stem as the material that precedes the theme vowel, e.g., just the root for E-Class [χəm-e-l] ‘to drink’ (Kogian, 1949; 82). We opt to include the theme vowel for easier contrasts, and because theme vowels are class-specific, root-specific, and are also involved in forming the aorist stem.

In Eastern Armenian, the causative’s past allomorph is -t͡sʰɾ- not -t͡su-. In the past perfective, the theme vowel and aorist suffix are optional and their use varies by formality: χəm-t͡sʰɾ-(e-t͡sʰ)-i-n [\(\sqrt{}\)-caus-th-aor-pst-3pl] ‘they caused to drink’ (Hagopian, 2005; 358; Dum-Tragut, 2009; 208).

Coincidentally, Lithuanian has a nasal infix (Ambrazas et al., 2006; 285ff). The nasal surfaces in morphomic present stems in some verbs, but not in the morphomic past stem nor the morphomic infinitive stem (Arkadiev, 2012). The Lithuanian nasal infix is likely diachronically related to the Armenian nasal infix. The infix displays morphomic behavior in both languages.

In the imperative 2sg, some Western speakers use a zero morph for the I-Class along with changing the -i- theme vowel to -e-: χos-e-∅ ‘speak (imp 2sg)’ (Boyacioglu, 2010; 37). This is a more archaic form. In Eastern Armenian, the imperative 2sg marker for the E-Class is -iɾ without a theme vowel: χəm-iɾ ‘drink!’. In fact, the imperative suffix is different for most verbs in Eastern Armenian, see paradigms in Dum-Tragut (2009; 271).

For the imperative 2pl, Eastern is more complicated than Western. The A-Class uses the aorist. For the E-Class, some sources say Eastern does use the aorist (Dum-Tragut, 2009; 271), but other sources report that an aorist-less form is nowadays more typical (the Eastern Armenian National Corpus: Khurshudian et al., 2009).

For the causative, whenever we expect the Western aorist stem X-t͡su-t͡s- with the aorist suffix, the Eastern form uses the cognate aorist stem X-t͡sʰɾ- without an aorist suffix. Contrast the imperative 2pl of the causative ‘to make read’ in Western ɡɑɾtʰ-ɑ-t͡su-t͡s-ekʰ vs. Eastern kɑɾtʰ-ɑ-t͡sʰɾ-ekʰ [\(\sqrt{}\)-th-caus-(aor)-2pl] (Dum-Tragut, 2009; 208). The imperative 2sg uses a unique Agr suffix -u: kɑɾtʰ-ɑ-t͡sʰɾ-u.

In the imperative 2sg, the causative suffix displays allomorphy to /-t͡su-/.

Within each irregular class, some utilize an overt imperative 2sg marker like ‘to arrive’ [hɑs-n-i-l] is inflected as [hɑs-iɾ]. But some use a bare root, e.g., ‘to take’ [ɑɾ-n-e-l] is inflected with a bare root [ɑɾ] ‘take!’. We set aside this variation as tangential.

Some Western speakers optionally change the -i- to -e- for the prohibitive 2pl: mi χos-e-kʰ (Hagopian, 2005; 359). In Eastern Armenian, prohibitive verbs use the same suffixes as imperatives: E-Class mi χəm-iɾ, A-Class mi kɑɾtʰ-a (Hagopian, 2005; 359). In Eastern Armenian, the prohibitives use the aorist if the corresponding imperative has the aorist, e.g., in imperative 2pl of the A-Class, but variably for the imperative 2pl of the E-Class.

Other less common participles include the future participles. These are formed by adding either the suffixes -ikʰ or -u to the infinitive: [ɡɑɾtʰ-ɑ-l-ikʰ, ɡɑɾtʰ-ɑ-l-u] from [ɡɑɾtʰ-ɑ-l] ‘to read’. We set them aside.

When the connegative is used for negating the past imperfective, the /-i-/ theme vowel changes to /-e-/ due to an independent morphophonological process (Dolatian, accepted).

The resultative is also called the perfect participle, and the evidential is also called the mediative. In Eastern Armenian, the resultative participle is not used in periphrasis, and there is no evidential participle. Instead, Eastern Armenian has an additional participle called the perfect participle or perfective converb with the suffix -el. It seems that this participle uses the aorist stem whenever the resultative participle does, similarly to the relationship between the resultative and evidential participles in Western Armenian Dum-Tragut (2009; 213).

For causativization and passivization, inchoatives generally resist these operations. The most unambiguous cases involve inchoative verbs which are actually transitive: əst-ɑ-n-ɑ-l ‘to receive’. Here, the inchoative morpheme is bleached of its inchoative meaning while it maintains its morphological behavior.

The /-i-/ theme vowel changes to /-e-/ before the causative suffix. A causative verb cannot be recausativized.

The infixed verb ‘to descend’ [it͡ʃ-n-e-l] is causativized without the infix but with the theme vowel, so it doesn’t truly use the aorist stem: [it͡ʃ-e-t͡sən-e-l] ‘to lower’. The suppletive verb ‘to eat’ ud-e-l is causativized with the aorist stem ɡer-t͡sən-e-l ‘to feed’. Some dictionaries also list forms with the present stem ud-e-t͡sən-e-l [\(\sqrt{}\)-th-caus-th-inf]. We speculate that the present-stem version is more common in Eastern Armenian than in Western.

It is a diachronic accident that the causative suffix allomorphs /-t͡sən-, -t͡su-, -t͡s-/ and aorist suffix /-t͡s-/ share the segment /t͡s/. The causative is historically derived from compounding the stem with the verb ‘to show’ X-ɑ-t͡sut͡sɑn-e-l [X-lv-show-th-inf] (Kortlandt, 1999). The causative morpheme is not synchronically related to the aorist. But in the sequence /-ɑ-t͡s-v-/, the /t͡s/ is formally ambiguous between being the causative marker of a passivized causative vs. the aorist of a passivized A-Class.

The passive triggers schwa epenthesis after a CC cluster as in the passive of ‘to touch’.

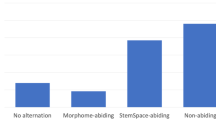

For the class count, we combine E-Class, I-Class, and Passives because they pattern the same. For BD, the verb list originally had 3257 lemmas, while UD had 1762 lemmas; we excluded 44 lemmas from BD and 38 lemmas from UD because these lemmas (and their inflected forms) were either obsolete, defective, were Eastern Armenian, or displayed variation in the choice of class depending on the paradigm cell.

Passive and causative tokens are doubly counted, e.g., resultative passives would count to both the Passive and Resultative columns. We exclude an additional 1119 tokens that used either obsolete, defective, heteroclitic, or Eastern conjugations.

As an anecdotal example for this point, before we did this study, we the authors naively thought that the aorist suffix -t͡s- was just a non-morphomic marker for perfectivity. Later while doing this study, we realized that this affix was used elsewhere in the paradigms as a meaningless element, such as in imperatives. This anecdote suggests that speakers may psycholinguistically process the aorist suffix/stem differently for different paradigm cells.

In more formal terms, such implicational dependencies are analogous to monotonicity (Graf, 2019; Moradi, 2019, 2020, 2021). Given some domain elements x,y and a function f, f is monotonic if x<y, then f(x)<f(y). More informally, because evidential participles are above (‘less’ than) subject participles in our base hierarchy, then if a verb’s subject participle uses an aorist stem, then so must its evidential, but not vice versa.

We thank Borja Herce for discussing this alternative explanation with us. A similar interpretation is that, because regular verbs display monotonicity, then a constructive approach is efficient for organizing regular verbs. In contrast, because irregular verbs are chaotic and seem to need cell-by-cell information, then an abstractive approach is more efficient for them (O’Neill, 2014).

For readers who don’t practice DM, we encourage them to see how their own preferred morphological model would differ from DM in formalizing the individual aspects of our analysis. We don’t think our model is empirically superior to another.

Following Trommer (2016)’s terminology, these insertion rules treat the aorist feature aor as a semi-parasitic feature. The feature is semi-parasitic because it is meaninglessly added in the Morphology for the imperative 2pl, while it is meaningfully added in the Syntax for the past perfective.

There is morphophonological evidence that the deleted theme vowels are exponed and overt at an earlier phonological cycle, syllabifying with the root, and then getting deleted before certain suffixes (Dolatian, in review). The theme deletion rule likewise cannot be a purely phonological rule. Although it is tempting to argue that a theme vowel is deleted to repair vowel hiatus *χəm-e-oʁ, the general hiatus repair rule in Armenian is glide epenthesis: mɑɾkʰɑɾe-ov → mɑɾkʰɑɾej-ov ‘prophet-ins’. Although deletion is possible when the first vowel is i before a derivational suffix (Dolatian, 2020, 2021), deletion is not a common repair rule for e or ɑ (Vaux, 1998). In fact, epenthesis is used to resolve vowel hiatus between theme vowels and Agr suffixes. In the past imperfective χəm-e-i-n ‘(If) they were to drink’ (§2.2), the surface form is pronounced with a glide [χəm-e-ji-n.]

The allomorph is also used in the imperative 2sg even though there is no spurious aorist (§3.1). This seems to be just arbitrary morphological conditioning.

But in terms of underlying morphological features (which trigger the feeding), the covert allomorphy is arguably non-self-destructive (Eric Baković, p.c).

In the past perfective 3sg, the irregular verb per-e-l shows idiosyncratic use of the T-Agr allomorphs /-ɑ-v/: pʰeɾ-ɑ-v [\(\sqrt{}\)-pst-3sg] ‘he brought’. The choice of this exponent requires referencing both the root and the covert aorist morpheme. If the aorist morpheme was absent, we would incorrectly expect the verb to take the same past markers as in the past imperfective 3sg: pʰeɾ-e-∅-ɾ [\(\sqrt{}\)-th-pst-3sg] ‘he was bringing’. It is the covert presence of the perfective aorist which licenses the right T and Agr morphs.

There is some cross-dialectal evidence for the deletion approach. In Western Armenian, the suppletive verb d-ɑ-l [\(\sqrt{}\)-th-inf] ‘to give’ has a suppletive root in the past perfective along with theme and aorist deletion: dəv-i-n [\(\sqrt{}\)-pst-3pl] ‘they gave’. In Eastern Armenian, we find suppletion but no deletion: təv-e-t͡sʰ-i-nʰ [\(\sqrt{}\)-th-aor-pst-3pl] ‘they gave’. Here we see that root allomorphy triggers deletion in Western, but not in Eastern.

It is an open question if the aorist stem was morphomic in Classical Armenian, and what were the necessary changes from Classical to Modern forms. It is also an open question if aorist or perfective stems in other areally-related Caucasian and Indo-European langauges are also morphomic (Daniel, 2018; Ganenkov, 2020; Belyaev, 2020; 607).

References

Ambrazas, V., Geniušienė, E., Girdenis, A., Sližienė, N., Tekorienė, D., Valeckienė, A., & Valiulytė, E. (2006). Lithuanian grammar. Vilnius: Baltos lankos.

Arkadiev, P. M. (2012). Stems in Lithuanian verbal inflection (with remarks on derivation). Word Structure, 5(1), 7–27. https://doi.org/10.3366/word.2012.0017.

Aronoff, M. (1994). Linguistic inquiry monographs: Vol. 22. Morphology by itself: stems and inflectional classes. London/Cambridge: MIT Press.

Arregi, K., & Nevins, A. (2012). Morphotactics: Basque auxiliaries and the structure of spellout (Vol. 86). Dordrecht: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-3889-8.

Atlamaz, Ü. (2019). Agreement, case, and nominal licensing. Rutgers University dissertation.

Baković, E. (2011). Opacity and ordering. In J. Goldsmith, J. Riggle, & A. C. L. Yu (Eds.), The handbook of phonological theory (2nd ed., Vol. 2, pp. 40–67). Oxford: Blackwell. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444343069.ch2.

Bardakjian, K. B., & Thomson, R. W. (1977). A textbook of modern Western Armenian. Delmar: Caravan Books.

Belyaev, O. (2020). Indo-European languages of the Caucasus. In M. Polinsky (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of languages of the Caucasus, Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190690694.013.6.

Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2013). The Spanish lexicon stores stems with theme vowels, not roots with inflectional class features. Probus, 25(1), 3–103. https://doi.org/10.1515/probus-2013-0009.

Bermúdez-Otero, R., & Luís, A. R. (2016). A view of the morphome debate. In The morphome debate (pp. 309–340). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.003.0012.

Blevins, J. P. (2006). Word-based morphology. Journal of Linguistics, 42(3), 531–573. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226706004191.

Bobaljik, J. D. (2000). The ins and outs of contextual allomorphy. In K. K. Grohmann & C. Struijke (Eds.), University of Maryland working papers in linguistics (Vol. 10, pp. 35–71). College Park: University of Maryland.

Bobaljik, J. D. (2012). Current studies in linguistics: Vol. 50. Universals in comparative morphology: suppletion, superlatives, and the structure of words. Cambridge: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9069.001.0001.

Bonami, O., & Boyé, G. (2002). Suppletion and dependency in inflectional morphology. In F. van Eynde, L. Hellan, & D. Beermann (Eds.), The proceedings of the HPSG’01 conference (pp. 51–70). Stanford: CSLI Publications.

Boyacioglu, N. (2010). Hay-Pay: Les verbs de l’arménien occidental. Paris: L’Asiatheque.

Boyacioglu, N., & Dolatian, H. (2020). Armenian verbs: Paradigms and verb lists of Western Armenian conjugation classes (v. 1.0.0). Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.4397423.

Calabrese, A. (2015). Irregular morphology and athematic verbs in Italo-Romance. Isogloss. Open Journal of Romance Linguistics. 69–102. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/isogloss.17.

Choi, J., & Harley, H. (2019). Locality domains and morphological rules. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 37(4), 1319–1365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-018-09438-3.

Dahl, Ö. (1985). Tense and aspect systems. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Daniel, M. (2018). Aspectual stems in three East Caucasian languages. In D. Forker & T. Maisak (Eds.), The semantics of verbal categories in Nakh-Daghestanian languages (pp. 247–266). Leiden/Boston: Brill. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004361805_010.

Dolatian, H. (2020). Computational locality of cyclic phonology in Armenian. Stony Brook University dissertation.

Dolatian, H. (2021). Cyclicity and prosodic misalignment in Armenian stems: interaction of morphological and prosodic cophonologies. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 39, 843–886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09487-7.

Dolatian, H., accepted. Output-conditioned and non-local allomorphy in Armenian theme vowels. The Linguistic Review.

Dolatian, H., in review. Cyclic dependencies in bound stem formation in Armenian passives. Unpublished manuscript.

Dolatian, H., & Guekguezian, P. A. (2021). Relativized locality: phases and tiers in long-distance allomorphy in Armenian. Linguistic Inquiry. https://doi.org/10.1162/ling_a_00456.

Donabédian, A. (1997). Neutralisation de la diathèse des participes en -ac de l’arménien moderne occidental. Studi italiani di linguistica teorica ed applicata, 26(2), 327–339.

Donabédian, A. (2016). The aorist in Modern Armenian: core value and contextual meanings. In Z. Guentchéva (Ed.), Aspectuality and temporality: descriptive and theoretical issues (Vol. 172, p. 375). Amsterdam: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/slcs.172.12don.

Dum-Tragut, J. (2009). Armenian: Modern Eastern Armenian. London oriental and African language library: Vol. 14. Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company. https://doi.org/10.1075/loall.14.

Embick, D. (1998). Voice systems and the syntax/morphology interface. In H. Harley (Ed.), Mitwpl 32: papers from the upenn/mit roundtable on argument structure and aspect (pp. 41–72). Cambridge: MITWPL, Department of Linguistics and Philosophy, MIT.

Embick, D. (2015). The morpheme: a theoretical introduction (Vol. 31). Boston/Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9781501502569.

Embick, D., & Halle, M. (2005). On the status of stems in morphological theory. In T. Geerts, I. van Ginneken, & H. Jacobs (Eds.), Current issues in linguistic theory: Vol. 270. Romance languages and linguistic theory 2003 (pp. 37–62). Ambsterdam: John Benjamins. https://doi.org/10.1075/cilt.270.03emb.

Embick, D., & Noyer, R. (2007). Distributed morphology and the syntax/morphology interface. In G. Ramchand & C. Reiss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of linguistic interfaces (Vol. 289, pp. 289–324). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199247455.013.0010.

Enger, H.-O. (2019). In defence of morphomic analyses. Acta Linguistica Hafniensia, 51(1), 31–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/03740463.2019.1594577.

Fairbanks, G. H. (1948). Phonology and morphology of modern spoken West Armenian. Madison: University of Wisconsin-Madison dissertation.

Fairbanks, G. H. (1958). Spoken West Armenian (Vol. 16). New York: American Council of Learned Societies.

Feist, T., & Palancar, E. L. (2021). Paradigmatic restructuring and the diachrony of stem alternations in Chichimec. Language, 97(1), 1–41. https://doi.org/10.1353/lan.2021.0000.

Ganenkov, D. (2020). Missing elsewhere: domain extension in contextual allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry, 51, 785–798. https://doi.org/10.1162/linga00358.

Georgieva, E., Salzmann, M., & Weisser, P. (2021). Negative verb clusters in Mari and Udmurt and why they require postsyntactic top-down word-formation. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory, 457–503. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-020-09484-w.

Giorgi, A. Haroutyunian, S. (2011). Remarks on temporal anchoring: the case of Armenian aorist. University of Venice Working Papers in Linguistics, 21, 89–110.

Golovko, E. V. (Ed.) (2018). Acta linguistica petropolitana. Transactions of the institute for linguistic studies. Part 1: the Armenian and Proto-indo-European preterite: forms and functions (Vol. 14 (1)). St. Petersburg: Russian Academy of Sciences.

Graf, T. (2019). Monotonicity as an effective theory of morphosyntactic variation. Journal of Language Modelling, 7(2), 3–47. https://doi.org/10.15398/jlm.v7i2.211.

Greppin, J. A. C. (1973). The origin of Armenian nasal suffix verbs. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung, 87(2), 190–198.

Gribanova, V. (2015). Exponence and morphosyntactically triggered phonological processes in the Russian verbal complex. Journal of Linguistics, 51(3), 519–561. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022226714000553.

Guekguezian, P. A. & Dolatian, H. in press. Distributing theme vowels across roots, verbalizers, and voice in Western Armenian verbs. Proceedings of the 39th. Meeting of the West Coast Conference on Formal Linguistics (WCCFL).

Hagopian, G. (2005). Armenian for everyone: Western and Eastern Armenian in parallel lessons. Ann Arbor: Caravan Books.

Haig, G. LJ. (2008). Alignment change in Iranian languages: a construction grammar approach (Vol. 37). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110198614.

Halle, M., & Marantz, A. (1993). Distributed morphology and the pieces of inflection. In K. Hale & S. J. Keyser (Eds.), The view from Building 20: studies in linguistics in honor of Sylvaln Bromberger (pp. 111–176). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Hamp, E. P. (1975). On the nasal presents of Armenian. Zeitschrift für vergleichende Sprachforschung, 89(1), 100–109.

Harley, H. (2014). On the identity of roots. Theoretical Linguistics, 40(3/4), 225–276. https://doi.org/10.1515/tl-2014-0010.

Herce, B. (2019). Morphome interactions. Morphology, 29(1), 109–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-018-09337-8.

Herce, B. (2020a). On morphemes and morphomes: Exploring the distinction. Word Structure, 13(1), 45–68. https://doi.org/10.3366/word.2020.0159.

Herce, B. (2020b). A typological approach to the morphome: University of Surrey dissertation.

Hornstein, N. (1990). As time goes by: tense and universal grammar. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Iatridou, S., Anagnostopoulou, E., & Izvorski, R. (2001). Observations about the form and meaning of the perfect. In M. Kenstowicz (Ed.), Ken Hale: a life in language (pp. 189–238). Cambridge: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110902358.153.

Johnson, E. W., & 1954). Studies in East Armenian grammar. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley dissertation.

Kalin, L., & Atlamaz, Ü. (2018). Reanalyzing Indo-Iranian “stems”: a case study of Adıyaman Kurmanji. In D. Ö. F.Akkuş & İ K.Bayırlı (Eds.), Proceedings of tu+1: Turkish, Turkic and the languages of Turkey (pp. 85–98).

Karakaş, A., Dolatian, H., & Guekguezian, P. A. (2021). Effects of zero morphology on syncretism and allomorphy in Western Armenian verbs. In Proceedings of the Sixth Workshop on Turkic and Languages in Contact with Turkic (TU+6) (Vol. 6). https://doi.org/10.3765/ptu.v6i1.5056.

Kaye, S. (2013). Morphomic stems in the Northern Talyshi verb: Diachrony and synchrony. In S. Cruschina, M. Maiden, & J. C. Smith (Eds.), The boundaries of pure morphology: diachronic and synchronic perspectives (pp. 181–208). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199678860.003.0010.

Khurshudian, V. G., Daniel, M. A., Levonian, D. V., Plungian, V. A., Polyakov, A. E., & Rubakov, S. A. (2009). Eastern Armenian National Corpus. In Computational linguistics and intellectual technologies (papers from the annual international conference “dialogue 2009” (Vol. 8/15, pp. 509–518). Moscow: RGGU.

Kim, R. I. (2018). The prehistory of the Classical Armenian weak aorist. In Golovko (2018) (pp. 86–136). https://doi.org/10.30842/alp2306573714104.

Kocharov, P. (2019). Old Armenian nasal verbs. Archaisms and innovations. Leiden University dissertation.

Kocharov, P. A. (2014). Derivational semantics of Classical Armenian č’-stems. Acta Linguistica Petropolitana. Труды института лингвистических исследований, 10(1), 202–226.

Kocharov, P. A. (2018). A note on the origin of the Old Armenian mediopassive endings. In Golovko (2018) (pp. 137–148). https://doi.org/10.30842/alp2306573714105.

Kogian, S. L. (1949). Armenian grammar (West dialect). Vienna: Mechitharist Press.

Koontz-Garboden, A. (2016). Thoughts on diagnosing morphomicity: a case study from Ulwa. In Luís and Bermúdez-Otero (2016) (pp. 89–111). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.003.0005.

Kortlandt, F. (1995). The sigmatic forms of the Armenian verb. Annual of Armenian Linguistics, 16, 13–17.

Kortlandt, F. (1987). Sigmatic or root aorist. Annual of Armenian Linguistics, 8, 49–52.

Kortlandt, F. (1999). The Armenian causative. Annual of Armenian Linguistics, 20, 47–49.

Kortlandt, F. (2018). The development of the sigmatic aorist in Armenian. In Golovko (2018) (pp. 149–152).

Luís, A. R., & Bermúdez-Otero, R. (2016). The morphome debate. Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.001.0001.

Maiden, M. (2016). Some lessons from history: morphomes in diachrony. In Luís and Bermúdez-Otero (2016) (pp. 33–63). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.003.0003.

Maiden, M. (2021). The morphome. Annual Review of Linguistics, 7, 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-linguistics-040220-042614.

Marantz, A. (2013). Locality domains for contextual allomorphy across the interfaces. In O. Matushansky & A. Marantz (Eds.), Distributed morphology today (pp. 95–115). Cambridge/London: MIT Press. https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/9780262019675.003.0006.

Martirosyan, H. (2018). The development of the Classical Armenian aorist in modern dialects. In Golovko (2018) (pp. 153–162).

Marvin, T. (2002). Topics in the stress and syntax of words. Massachusetts Institute of Technology dissertation.

Merchant, J. (2015). How much context is enough? Two cases of span-conditioned stem allomorphy. Linguistic Inquiry, 46(2), 273–303. https://doi.org/10.1162/LINGa00182.

Moradi, S. (2019). *ABA generalizes to monotonicity. In M. Baird & J. Pesetsky (Eds.), Proceedings of NELS 49 (Vol. 2). Amherst: GSLA University of Massachusetts. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-62843-08.

Moradi, S. (2020). Morphosyntactic patterns follow monotonic mappings. In D. Deng, F. Liu, M. Liu, & D. Westerståhl (Eds.), Monotonicity in logic and language (pp. 147–165). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-662-62843-0_8.

Moradi, S. (2021). Monotonicity in morphosyntax. Stony Brook University

Nevins, A., Rodrigues, C., & Tang, K. (2015). The rise and fall of the L-shaped morphome: Diachronic and experimental studies. Probus, 27(1), 101–155. https://doi.org/10.1515/probus-2015-0002.

Newell, H. (2008). Aspects of the morphology and phonology of phases. Montreal: McGill University dissertation.

Oltra-Massuet, I. (1999). On the constituent structure of Catalan verbs. In K. Arregi, V. Lin, C. Krause, & B. Bruening (Eds.), MIT working papers in linguistics (Vol. 33, pp. 279–322). Cambridge: Department of Linguistics, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

O’Neill, P. (2014). The morphome in constructive and abstractive models of morphology. Morphology, 24(1), 25–70. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-014-9232-1.

Plungian, V. (2018). Notes on Eastern Armenian verbal paradigms: “temporal mobility” and perfective stems. In D. Van Olmen, T. Mortelmans, & F. Brisard (Eds.), Aspects of linguistic variation: studies in honor of Johan van der Auwera (pp. 233–245). Berlin: de Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110607963-009.

Round, E. R. (2016). Kayardild inflectional morphotactics is morphomic. In Luís and Bermúdez-Otero (2016) (pp. 228–247). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.003.0009.

Smith, C. S. (1997). The aspectual system of Mandarin Chinese. In The parameter of aspect (pp. 343–390). Berlin: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-011-5606-611.

Steriade, D. (2016). The morphome vs. similarity-based syncretism: Latin t-stem derivatives. In Luís and Bermúdez-Otero (2016) (pp. 112–172). https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198702108.003.0006.

Stump, G. (2001). Inflectional morphology: a theory of paradigm structure. Cambridge studies in linguistics: Vol. 93. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511486333.

Trommer, J. (2012). Oxford studies in theoretical linguistics: Vol. 41. The morphology and phonology of exponence (pp. 326–354). Oxford: Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199573721.003.0010.

Trommer, J. (2016). A postsyntactic morphome cookbook. In D. Siddiqi & H. Harley (Eds.), Linguistik aktuell/linguistics today: Vol. 229. Morphological metatheory (pp. 59–93). https://doi.org/10.1075/la.229.03tro

Vaux, B. (1995). A problem in diachronic Armenian verbal morphology. In J. Weitenberg (Ed.), New approaches to medieval Armenian language and literature (pp. 135–148). Amsterdam: Rodopi.

Vaux, B. (1998). The phonology of Armenian. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Yavrumyan, M. M. (2019). Universal dependencies for Armenian. In International conference on digital Armenian, Inalco, Paris, October 3-5.

(1962).

(1962).  [The verb in Modern Armenian].

[The verb in Modern Armenian].  .

.

(2004).

(2004).  [Correspondences of derivative verbs of Classical Armenian in Western Armenian].

[Correspondences of derivative verbs of Classical Armenian in Western Armenian].  2, 178-185

2, 178-185

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Dolatian, H., Guekguezian, P. Derivational timing of morphomes: canonicity and rule ordering in the Armenian aorist stem. Morphology 32, 317–357 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09397-x

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11525-022-09397-x

,

,  (1962).

(1962).  [The verb in Modern Armenian].

[The verb in Modern Armenian].  .

.

(2004).

(2004).  [Correspondences of derivative verbs of Classical Armenian in Western Armenian].

[Correspondences of derivative verbs of Classical Armenian in Western Armenian].  2, 178-185

2, 178-185