Abstract

Previous studies have shown that addiction is associated with an attentional bias towards external stimuli. However, it is currently unclear whether this bias extends to internal attention. The aim of the present study was to address this question within the Incentive Sensitization theory framework. To this end, structural equation models delineating the relationships between nicotine dependence, the imbalance of wanting and liking (WmL), personal relevance of smoking consequences, and antismoking intention were tested using online survey data of 826 tobacco users. Consistent with previous findings, WmL was disrupted with increasing nicotine dependence. The key finding was that a moderate positive correlation was observed between WmL and personal relevance of positive consequences, which suggests that dependence-related attentional bias might not only relate to the processing of external stimuli but also to what an individual considers important, which is linked to the distribution of internal attention. However, such attentional bias might not apply to all smokers to the same extent, based on the comparison of latent profiles of smokers. The findings indicate that the bias of internal attention may play a significant role in both the initiation of smoking cessation, as well as in the likelihood of relapse. This suggests that including a more diverse array of topics in health communication could be beneficial, given the varying emphasis on smoking consequences among different profiles.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Attention is a critical cognitive process that underlies many of our everyday activities. One of the main functions of attention is to enhance perception and sensory processing by selectively attending to specific features of stimuli in the environment (Petersen & Posner, 2012). Attention also plays a crucial role in learning and memory. Studies have shown that attentional processes can enhance encoding and retrieval of information, leading to better memory performance (Craik & Lockhart, 1972; Vogel et al., 2005). Furthermore, attentional processes have been implicated in a variety of higher-level cognitive tasks, including decision-making, problem-solving, and language processing (Cowan, 2001); thus, attention is essential for goal-directed behavior, allowing us to focus on the task at hand and ignore irrelevant stimuli (Posner & Petersen, 1990). Attentional mechanisms also play a crucial role in the onset and maintenance of various psychological disorders, such as anxiety disorders (Bar-Haim et al., 2007; Etkin & Wager, 2007), schizophrenia (Luck & Gold, 2008), or depression (Gotlib & Joormann, 2010). Attentional bias is a phenomenon commonly observed in individuals with addiction, as they exhibit a greater sensitivity to substance-related cues in their environment, leading to a strong inclination towards substance-seeking behaviors. The Incentive Sensitization Theory (IST) provides a comprehensive framework describing how the attentional mechanism contributes to the maintenance and relapse of addictive behaviors (Robinson & Berridge, 2000). Briefly, the IST suggests that separate neural mechanisms are accountable for the motivational (wanting) and hedonic (liking) impacts of a substance. With tolerance affecting liking and sensitization affecting wanting, recurrent substance use can disrupt the equilibrium between these two systems, causing an increase in wanting along with stable or reduced liking. Consequently, individuals with substance use disorders may experience a contradictory situation where they desire a substance despite not expecting it to bring them pleasure (Robinson & Berridge, 2001). The psychological process behind wanting involves the attribution of attracting salience to stimuli and their representations, which is believed to alter the neural and psychological representations of ordinary stimuli, making them highly salient and attention-grabbing (Robinson & Berridge, 2000). This attentional bias leads individuals to allocate disproportionate attention to drug-associated stimuli, often at the expense of other relevant environmental cues (Field & Cox, 2008). This heightened salience of drug cues is believed to be driven by sensitized incentive salience attributed to drug-related stimuli. According to Robinson & Berridge (1993), the incentive salience of drug cues becomes hyper-responsive and persists over time, even in the absence of conscious craving. Consequently, attentional processes become selectively attuned to drug-related cues, perpetuating the cycle of drug-seeking behavior and contributing to the maintenance of addiction (Field & Cox, 2008; Franken, 2003). The relationship between addiction and IST has been a subject of extensive research across various addictive behaviors. In the context of smoking, Grigutsch et al., (2019) showed that implicit wanting and implicit liking for smoking cues are decoupled in smokers (i.e., increased wanting for smoking cues), and individuals with a history of chronic smoking exhibit sensitized responses to smoking-related cues, indicating an amplified incentive salience attributed to these stimuli (Carter & Tiffany, 1999). Similarly, in the context of substance use disorders, IST has been invoked to elucidate behaviors associated with specific substances, such as cocaine (Lambert et al., 2006) or alcohol (Ostafin et al., 2010). Furthermore, in the domain of eating behaviors, research has investigated how incentive sensitization contributes to the development and maintenance of addictive eating patterns, particularly in the context of highly palatable and calorie-dense foods (Berridge, 2009) and in cue-rich environments (Joyner et al., 2017).

The presence of such attentional sensitization towards external stimuli has been demonstrated in a number of studies. External attention concerns the process of choosing and regulating sensory information as it enters the mind, usually in a modality-specific form with episodic tags for spatial locations and temporal points (Chun et al., 2011). For example, facilitated information processing was reported for visual stimuli related to addictive behavior in the case of marihuana use (Field, 2005), alcohol use (Townshend & Duka, 2001), tobacco use (Field et al., 2009a, b), cocaine use (Liu et al., 2011), or internet use (Nikolaidou et al., 2019). The general pattern in these studies is that individuals with an addiction (compared to a control group) notice changes quicker, respond quicker, and are less effective in inhibiting distracting visual stimuli if the stimuli are related to the addiction in question.

On the other hand, internal attention pertains to the selection and regulation of internally generated information, such as the contents of working memory, long-term memory, task sets, or response selection. Similar to how external attention is limited in its capacity, there are also strict limits on the number of items that can be stored in working memory, the number of choices that can be made, the number of tasks that can be performed, and the number of responses that can be produced simultaneously (Chun et al., 2011). Working memory is supposed to act as a mediator between perception and long-term memory, and it heavily depends on internal attention to receive and process new perceptual information and to retrieve previously stored representations from long-term memory to aid in behavior (Narhi-Martinez et al., 2023). An indirect way to assess internal attention is through the investigation of personal relevance, as it is a critical factor that affects internal attention. It enhances the allocation of attention to personally relevant stimuli, as well as the quality of processing and memory for those stimuli. For example, individuals with social anxiety paid more attention to socially relevant stimuli in their own thoughts than to non-social stimuli (Amir et al., 2009). Similarly, individuals with high levels of worry focused more on worry-relevant thoughts than on non-worry thoughts (Brosschot et al., 2006). Personal relevance also affects the quality of internal attention. When a stimulus is personally relevant, it is more likely to be processed deeply and remembered better (Kensinger & Corkin, 2003), probably because personal relevance increases the motivation to attend to the stimulus, leading to greater engagement and processing resources. Furthermore, personal relevance can also influence the regulation of internal attention. When a stimulus is personally relevant but also emotionally arousing, it can lead to increased rumination and difficulty disengaging from the stimulus (McLaughlin & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2011), probably because emotionally arousing stimuli capture attention involuntarily, leading to reduced attentional control.

The authors contend that it is reasonable to assume that the attentional bias observed in addictive behaviors might not only relate to the attentional mechanisms involved in processing external stimuli, but also to those involved in internal attention. Considering the strong connection between personal relevance (PR) and internal attention, this study aimed to examine the associations between the perceived significance of both positive and negative aspects of nicotine dependence and the balance between wanting and liking (WmL). We hypothesized that nicotine dependence would exacerbate the disparity between one’s desire and enjoyment for smoking (H1), which would be linked to an increase in PR attributed to the positive outcomes (H2), decreasing the intention to quit smoking (H3). Also, a negative association between WmL and intention to quit smoking was hypothesized (H4). Further, it was hypothesized that WmL would show a negative association with PR of negative consequences of smoking (H5), and a positive association between PR of negative consequences and intention to quit could be observed (H6). A direct negative association was assumed between nicotine dependence and intention to quit smoking (H7). Further, we hypothesized that nicotine dependence mediated by WmL would have a negative association with intention to quit (H8) and with PR of negative consequences (H9) and a positive association with PR of positive consequences (H10). Further, we hypothesized that WmL mediated by PR of negative and positive consequences would have a negative association with intention to quit (H11 and H12, respectively). Finally, given that the degree and direction of attentional bias caused by addiction can differ among individuals (Field et al., 2009a, b; Rinck et al., 2005), latent profiles were created based on the perceived significance of smoking consequences to examine whether comparable individual variations existed in WmL and smoking behavior and intention to quit between profiles.

Methods

Procedure and Participants

An online survey was conducted from July to August 2022 to collect data from popular Hungarian news portals. The survey was advertised as a research project focusing on the psychological factors of tobacco smoking, and participants were required to provide informed consent and were assured of their anonymity. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the institutional ethical review board of [BLINDED FOR REVIEW]. Data were collected using a secure online platform (Qualtrics Research Suite; Qualtrics, Provo, UT), and no personal information that could allow for personal identification was requested. To determine the minimum required sample size, we followed Kline’s (2016) conservative recommendation of maintaining a 20:1 ratio of observations to estimated parameters. Given that the analysis plan involved causal models for latent profiles, and the number of profiles was not predetermined, we targeted a final sample size of at least 800 subjects.

Participants who were aged 18 years or older, current smokers, and provided informed consent were included in the study. Out of the 1263 respondents who started the survey, 256 (20.26%) did not complete it, and 181 (12.3%) reported not being a smoker. The remaining 826 participants (484 men, 58.6%) who completed the survey were between the ages of 18 and 84 years (mean age = 39.9 years, SD = 13.36). The education level of the participants was distributed as follows: less than 1% had primary education, 15.0% reported having a vocational degree, a further 19.0% had a high school degree, and 65.5% had a college or university degree. In terms of relationship status, 24.1% were single, 73.9% were in some form of romantic relationship (i.e., being in a romantic relationship or married), and 2.0% selected the “other” option.

Measures

Nicotine Dependence

The level of nicotine dependence was assessed using the Hungarian adaptation (Urbán et al., 2004) of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence (refer to Heatherton et al., 1991), which comprises six items that evaluate cigarette consumption, compulsion to use, and dependence (e.g., How soon after waking do you smoke your first cigarette? (0) after 60 min; (1) 31 to 60 min; (2) 6 to 30 min; (3) within 5 min). Scores range from 0 to 10, with higher scores indicating greater physical dependence on nicotine. Additionally, years of smoking and average number of cigarettes/day were assessed.

Intention to Quit Smoking

The transtheoretical model was used to assess quitting intentions and past behavior (see DiClemente & Prochaska, 1998). Three questions were asked to assess participants’ intentions: (1) Do you plan to quit smoking? (rated on a 5-point scale from 1—certainly not to 5—certainly yes); (2) When do you plan to quit smoking? (options included within a week, within a month, within 6 months, within 12 months, within 5 years, within 10 years, over 10 years, and do not plan); (3) How important is it for you to quit smoking? (rated on a 5-point scale from 1–not at all to 5–extremely). Participants were also asked one question to assess past quitting attempts: “Have you attempted to quit smoking in the last 12 months?” (yes or no). Additionally, participants were asked to indicate the extent to which they regret smoking with the statement, “I wish I had never started smoking,” rated on a 5-point scale from 1—totally disagree to 5—totally agree.

Personal Relevance of Smoking Consequences

To assess the focus of internal attention directed towards smoking-related consequences, participants were prompted to evaluate the significance of smoking-related consequences on their own lives. A total of 14 items were used, with seven items pertaining to positive consequences (PR-positive) and seven items to negative consequences (PR-negative). These items were derived from various sources, including literature that presented perceived consequences of smoking, reasons for quitting smoking, and motivation to smoke (Brandon & Baker, 1991; Copeland et al., 1995; Stanaway & Watson, 1980; Turner & Mermelstein, 2004; Vangeli & West, 2008). The 14 identified consequences were categorized into the following: social, health, enhancement, financial harms, cognitive facilitation, lifestyle, emotional/psychological harms, relationship harms, recreation, coping, craving, energy, appearance, and weight control (e.g., It helps me to manage my weight.). Participants were asked to indicate the importance of each consequence in their own life using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1–not at all to 5–very important. For the items, see Appendix 2.

Wanting and Liking

Wanting and liking was measured with the Imaginative Wanting and Liking Questionnaire (see File et al., 2022). The questionnaire consists of micro-scenarios in which participants are asked to imagine themselves in situations related to substance or behavior use. In this study, participants were asked to envision themselves holding a cigarette in the appropriate time and location. Following the imagery call, participants are required to report their expected emotions using a ruler that ranges from − 100 (very bad) to 100 (very good) before, during, and after the cigarette, with three items: (1) How would you feel right before you lit the cigarette? (2) How would you feel during smoking? (3) How would you feel after you finished the cigarette? Additionally, participants are asked to estimate the level of willpower that they would need to resist or stop participating in smoking before, during, and after smoking, using a scale that ranges from 0 (nothing) to 100 (enormous), with the following items: (1) How much willpower would you need to not lit the cigarette and to not smoke in the next 24 h? (2) How much willpower would you require to resist finishing the cigarette after taking a few puffs and to not smoke in the next 24 h? (3) How much willpower would you need in order to not smoke in the next 24 h after you finish the cigarette? WmL scores were created for three time points—before, during, and after smoking the cigarette—and these scores were used in the analyses.

Analyses

To define possible sub-groups of smokers with similar patterns of personal relevance of smoking consequences (i.e., PR-positive and PR-negative, see above), a series of latent profile analyses were performed. Latent profile modeling represents a parametric method for illustrating unobserved subgroups of a population (see Collins & Lanza, 2009). The number of latent profiles was determined using an information-theoretic method, using Bayesian information criteria (BIC) and Integrated Completed Likelihood (ICL) (see Nylund et al., 2007; Bertoletti et al., 2015) criteria when choosing the most appropriate solution. Lower values on the ICL and BIC indicate a better fit. To investigate possible differences between profiles, profiles were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis test (see Table 1) and Bonferroni corrected pairwise Wilcoxon tests (see Appendix 1). In order to account for the increased possibility of type-I error resulting from the 14 comparisons, a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.0035 (0.05/14) was used.

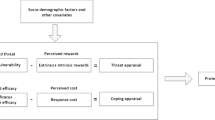

Structural equation modeling (SEM) with latent variables was conducted to examine the relationship pattern between nicotine dependence (total score of the Fagerström Test for Nicotine Dependence), WmL (latent variable was formed from the Imaginative Wanting and Liking Questionnaire WmL-before, -after and -during scores), personal relevance of smoking consequences (latent variables were formed from the PR-positive and PR-negative scores), and intention to quit smoking (latent variable was formed from the three items of intention to quit scale (i.e., items “Do you plan to quit smoking?”; “When do you plan to quit smoking?”; “How important is it for you to quit smoking?”)) (Fig. 1). Further, to observe possible differences between the groups defined by smoking motivations (i.e., Neutral, Cost-focused, Gain-focused), the same model was tested separately in the three profiles. When assessing the models, multiple goodness of fit indices were evaluated (Brown, 2015) with good or acceptable values based on the following thresholds (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Marsh et al., 2005). Regarding the comparative fit index (CFI) and Tucker–Lewis index (TLI), values higher than 0.95 indicated that a model had a good fit, whereas values higher than 0.90 indicated that a model had an acceptable fit. Regarding the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA) with its 90% confidence interval (90% CI), a model can be considered good if its RMSEA value is below 0.06, whereas it can be considered acceptable if this value is below 0.08. In addition, to examine the significance of indirect pathways in the mediation model, 95% bias-corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals (CIs) with 5000 resamples were computed.

The normality of the dependent variables was examined and did not violate the thresholds of Kim (2013), neither for skewness (ranging from − 0.96 to 0.60), nor for kurtosis (ranging from − 1.36 to 0.48) values. Notwithstanding, the distribution plots of some variables showed deviations from the normal distribution; thus, we used the diagonally weighted least squares (DWLS) estimator as recommended for data with non-normal distribution in SEM (Finney & DiStefano, 2006; Flora & Curran, 2004; Yang-Wallentin et al., 2010). In order to account for the increased possibility of type-I error (Cribbie, 2000), a Bonferroni-adjusted significance level of 0.0125 (0.05/4) was calculated based on the four predictor variables in the tested models.

Results

The sample consisted of 826 participants (484 men, 58.6%) who were between the ages of 18 and 84 years (mean age = 39.9 years, SD = 13.36). The average Fagerström nicotine dependence score was 4.30 (SD = 2.86), which indicates moderate dependence.

On the basis of the personal relevance of smoking consequences, latent profile models were estimated. Results of latent profile analyses indicated an optimal 3-profile solution (BIC: − 30032.47, ICL: − 30388.13). For model solutions, see Appendix 4. Profiles were labeled “Neutral” (N = 325), “Cost-focused” (N = 283), and “Gain-focused” (N = 218). Individuals classified as having a Neutral profile placed little significance on both positive and negative aspects of smoking. On the other hand, those with a Cost-focused profile gave greater importance to the negative aspects of smoking, while individuals with a Gain-focused profile attributed greater importance to the positive aspects of smoking.

For mean PR scores, see Appendix 2, and for a graphical representation of the 3 profiles, see Fig. 2. Kruskal–Wallis H tests showed significant differences in the age of the participants (χ2 = 16.16, p < 0.001, df = 2), level of nicotine dependence (χ2 = 36.90, p < 0.001, df = 2), number of cigarettes smoked per day (χ2 = 24.84, p < 0.001, df = 2), years of smoking (χ2 = 7.45, p = 0.02, df = 2), regret of having started smoking (χ2 = 38.86, p < 0.001, df = 2), certainty about quitting smoking (χ2 = 99.72, p < 0.001, df = 2), its planned time (χ2 = 91.20, p < 0.001, df = 2) and its perceived importance (χ2 = 128.17, p < 0.001, df = 2), and failed quit attempt in the past 12 months (χ2 = 32.34, p < 0.001, df = 2) between the three groups. Further, the Kruskal–Wallis H test indicated significant differences between groups in incentive sensitization-related variables: WmL before use (χ2 = 19.75, p < 0.001, df = 2) and WmL after use (χ2 = 17.38, p < 0.001, df = 2) (Appendix 3). For mean values, see Table 1.

Correlations between the variables included in the SEM analyses are reported in Table 2. The structural equation model on the full dataset showed an acceptable fit to the data: CFI of 0.951, TLI of 0.943, and an RMSEA of 0.059 [0.054, 0.064]. The analyses showed (see Table 3) that nicotine dependence had a strong positive association with WmL (β = 0.620 (95% CI: 0.533, 0.706), p < 0.001); that is, higher nicotine dependence was associated with greater “wanting,” compared to “liking.” WmL had a moderate positive association with importance attributed to positive consequences of smoking (β = 0.423 (95% CI: 0.327, 0.519), p < 0.001), but no significant association was observed with importance attributed to negative consequences. Unexpectedly, WmL had a moderate positive association with intention to quit smoking (β = 0.378 (95% CI: 0.188, 0.568), p < 0.001), suggesting that higher “wanting” compared to “liking” is associated with elevated reported intention to quit. Further, PR-negative had a strong positive association with intention to quit (β = 0.637 (95% CI: 0.582, 0.692), p < 0.001), while PR-positive (β = − 0.185 (95% CI: − 0.294, − 0.076), p = 0.001) and nicotine dependence (β = − 0.242 (95% CI: − 0.376, − 0.108), p = 0.001) had a weak negative association with intention to quit. Nicotine dependence mediated by WmL had a weak positive association with intention to quit (β = 0.234 (95% CI: 0.097, 0.371), p = 0.001) and with PR-positive (β = 0.262 (95% CI: 0.178, 0.346), p = 0.001). Finally, WmL mediated by PR-positive had a weak negative association with intention to quit smoking (β = − 0.078 (95% CI: − 0.130, − 0.027), p = 0.001). Overall, the model explained 17.9% of the variance of PR-positive and 0.3% of PR-negative, 38.4% of WmL, and 50.2% of intention to quit smoking.

The structural equation model showed an acceptable fit to the data of the Neutral profile: CFI of 0.928, TLI of 0.917, and an RMSEA of 0.059 [0.050, 0.068]. The analyses showed (see Table 4 (part A)) that nicotine dependence had a moderate positive association with WmL (β = 0.519 (95% CI: 0.424, 0.614), p < 0.001); that is, the higher nicotine dependence was, the greater “wanting” was reported, compared to “liking.” Further, PR-negative had a strong positive association with intention to quit (β = 0.615 (95% CI: 0.547, 0.684), p < 0.001), while nicotine dependence had a weak negative association with intention to quit (β = − 0.175 (95% CI: − 0.309, − 0.041), p = 0.012). Nicotine dependence had a weak positive indirect effect on PR-positive (β = 0.219 (95% CI: 0.163, 0.274), p < 0.001) mediated by WmL. Overall, the model explained 17.8% of the variance of PR-positive and 3.3% of PR-negative, 26.9% of WmL, and 47.4% of intention to quit smoking.

The structural equation model showed an acceptable fit to the data of the Cost-focused profile: CFI of 0.944, TLI of 0.936, and an RMSEA of 0.054 [0.044, 0.064]. The analyses showed (see Table 4 (part B)) that nicotine dependence had a strong positive association with WmL (β = 0.655 (95% CI: 0.556, 0.754), p < 0.001), and a moderate positive association with PR-positive (β = 0.331 (95% CI: 0.267, 0.395), p < 0.001), mediated by WmL. Further, WmL had a moderate positive association with PR-positive (β = 0.505 (95% CI: 0.433, 0.578), p < 0.001), and PR-negative had a moderate positive association with intention to quit smoking (β = 0.453 (95% CI: 0.386, 0.519), p < 0.001). Overall, the model explained 25.5% of the variance of PR-positive and 1.1% of PR-negative, 42.9% of WmL, and 27.1% of intention to quit smoking.

The structural equation model showed an acceptable fit to the data of the Benefit-focused profile: CFI of 0.949, TLI of 0.941, and an RMSEA of 0.052 [0.040, 0.064]. The analyses showed (see Table 4 (part C)) that nicotine dependence had a moderate positive association with WmL (β = 0.555 (95% CI: 0.431, 0.680), p < 0.001). PR-negative had a moderate positive association with intention to quit smoking (β = 0.451 (95% CI: 0.385, 0.517), p < 0.001). Overall, the model explained 4.9% of the variance of PR-positive and 0.1% of PR-negative, 30.8% of WmL, and 23.7% of intention to quit smoking.

Discussion

One contributing factor to the development and maintenance of addictive behaviors is attentional bias, which refers to the tendency for individuals with substance use disorders to selectively attend to drug-related stimuli while ignoring other information in their environment. This bias can lead to increased cravings, negative affect, and relapse. While there is a large body of evidence of external attentional bias in individuals with substance use disorders, such as those addicted to marihuana, alcohol, cocaine, and nicotine (Field, 2005; Field et al., 2009a, b, 2010; Liu et al., 2011; Townshend & Duka, 2001), the connection between addiction and internal attentional bias has remained unexplored. The objective of the present study was to explore the associations between nicotine dependence, wanting and liking of smoking, and their impact on the perceived significance of positive and negative consequences of smoking (which can be considered an indirect measure of internal attention, see “Introduction” section) and examine the associations between these factors and the intention to quit smoking.

In general, the results of the present study can be meaningfully interpreted within the IST framework. According to IST (Robinson & Berridge, 1993), the transition from causal use to compulsive use is the consequence of the sensitization of the motivational system, while changes in the hedonic system are less pronounced and are considered as a side-effect (Berridge et al., 2009). The findings of the current study support this theory, as the balance between wanting and liking was disturbed (i.e., their difference increased) with increasing nicotine dependence. Similar outcomes have been observed in studies investigating tobacco smoking (Grigutsch et al., 2019), excessive food consumption (Adams et al., 2019), overuse of social media (Ihssen & Wadsley, 2021), alcohol use (Hobbs et al., 2005), and cocaine use (Goldstein et al., 2010). Contrary to the expectations, a positive association was observed between WmL and intention to quit, while nicotine dependence showed a negative association with the intention to quit. These findings suggest that drawing attention to wanting and liking of substance use could be a useful aspect of intervention techniques, and further research in this area may be warranted.

The key finding of the current study was that a significant association was observed between WmL and PR of positive consequences, while no association was present between WmL and the PR of negative consequences. This suggests that dependence-related attentional bias may not only relate to the processing of external stimuli but may also contribute to what an individual considers important, which is linked to the distribution of internal attention. Prior research has suggested that the bias of external attention can contribute to the development and maintenance of addictive behaviors by reinforcing substance-seeking behavior and triggering cravings (Field & Cox, 2008). Similarly, PR can affect cognition in a variety of ways. For example, it relates to the allocation of external attention. When a stimulus is personally relevant, it is more likely to capture attention and be processed deeply (Murray & Wojciulik, 2004), probably because PR increases the motivation to attend to the stimulus, leading to greater engagement and processing resources (Pessoa, 2019). Moreover, one study showed that participants paid more attention to words that were personally relevant to them than to words that were irrelevant (Symons & Johnson, 1997). Also, when information has a high PR, they exhibited an improved ability to identify pertinent details (Sui & Gu, 2017), further indicating that PR enhances external attention. Also, personally relevant information is better remembered than information that is not relevant (Kensinger & Corkin, 2003), potentially as PR increases the depth of processing and the encoding of the information into memory, indicating the impact of PR on memory.

On the other hand, apart from its broad impact on cognition, PR has a direct influence on decision-making, as indicated by the strong direct link between PR of negative consequences of smoking and intention to quit, which aligns with previous studies. Borland et al. (2010) showed that smokers who viewed the health consequences of smoking as important were more inclined to express a desire to quit smoking compared to those who did not, while Fishbein et al. (2002) reported that those who perceived the social and psychological negative consequences of smoking as important were more likely to report an intention to quit smoking. On the other hand, high PR attributed to positive consequences of smoking can act as a barrier to quitting smoking, as indicated by the negative association between PR to positive consequences and intention to quit smoking. This finding is also consistent with previous studies (e.g., Borland et al., 2010), reporting that smokers who valued the pleasure associated with smoking were less likely to express a desire to quit smoking compared to those who did not.

Moreover, considering the strong relationship between WmL and PR and its direct effect on intention to quit, the secondary aim of the study was to identify sub-groups of smokers based on PR of smoking consequences and to test possible differences regarding WmL and smoking behavior between them. Three profiles of smokers were identified: individuals in the first profile attributed relatively low importance for both positive and negative aspects of smoking (Neutral, N = 325), individuals in the Cost-focused profile attributed greater importance for the negative aspects of smoking (N = 283), while individuals in the Gain-focused profile attributed greater importance for the positive aspects of smoking (N = 218). Meaningful differences emerged between individuals belonging to the three profiles. Individuals showed higher levels of nicotine dependence in the Gained-focused profile and lower level of intention to quit smoking compared to individuals in the other two profiles. Further, individuals in the Cost-focused profile showed the highest willingness to quit smoking. Also, reported WmL before smoking differed among profiles, showing the lowest imbalance in the Neutral profile, and the highest in the Benefit-focused profile. These results suggest that meaningful profiles of smokers can be identified based on PR and strengthen the notion that vulnerability to nicotine dependence might vary across individuals. The cross-sectional design of the study limits the interpretation of the results; however, a few explanations may be proposed. Importantly, reported years of smoking cannot account for the differences between profiles (~ 18 years of smoking on average, see Table 1); thus, the three profiles likely do not reflect different stages of nicotine dependence. The application of structural equation models on the three distinct profiles demonstrated varying degrees of influence of WmL on attention. WmL had a weaker effect on the PR of individuals in the Neutral profile in comparison to those in the Cost-focused profile, where it strongly correlated with an increase in PR of the favorable aspects of smoking. While the PR of positive smoking aspects did not relate to the intention to quit directly in Cost-focused profile, it is plausible that its relevance becomes apparent when a smoker attempts to quit, considering the higher rate of unsuccessful quit attempts among individuals in the Cost-focused profile. This assumption is consistent with the predictions of the IST, which posits that the sensitized motivational system holds significant importance in the occurrence of relapse (Berridge et al., 2009). According to the “elaborated intrusion” theory of desire (Kavanagh et al., 2005), subjective substance craving can manifest as an unwelcome intrusion. Once recognized, individuals may delve deeper into the craving by fixating on the craving itself or paying attention to external cues that triggered it, such as seeing someone smoking (Field & Cox, 2008). The current results suggest that such elaboration on craving might not only be influenced by external cues, but elevated PR of positive aspects can shape the content of their thinking process, potentially increasing the likelihood of use/relapse.

In addition, while the strong positive association between dependence and WmL applies to all three smoker profiles, the effect of WmL on PR does not reflect a uniform mechanism, corroborating the findings of prior studies. Robinson & Berridge (2001) reported that there is variability in the extent of sensitization to a particular substance dosage among individuals. Some individuals exhibit a rapid and pronounced sensitization response, whereas others may demonstrate minimal or no sensitization. Further studies would be necessary to delineate the link between proneness to nicotine dependence and other factors, such as genetics (Sullivan & Kendler, 1999), cultural background (Jha et al., 2006), stress (McKee et al., 2011), and personality characteristics (Choi et al., 2017). Nevertheless, different quitting intentions and previous quitting attempts observed between the three profiles indicate markedly different smoking behavior, which supports the importance of using multiple and/or personalized intervention programs (Bold et al., 2018). Further, considering the different focus on the consequences of smoking among profiles, the use of more diverse topics in health communication would potentially be beneficial. Nowadays, the majority of antismoking messaging revolves around threatening messages that depict the health consequences of smoking (e.g., Beaudoin, 2002; Leshner et al., 2011; Ruiter et al., 2014), which might be effective for those in the Neutral- and Gain-focused profiles (~ 66% of the current sample). However, individuals classified as Cost-focused may benefit more from promoting pharmacotherapy or the positive aspects of smoke-free life.

Limitations and Future Directions

The current findings provide useful insights into how incentive sensitization might relate to personal relevance and quitting intention. As a limitation; however, it is important to acknowledge that a self-report method was used to assess wanting and liking instead of behavioral paradigms, such as the visual probe task (Bradley et al., 2003) or the Wanting-Implicit-Association Test (Grigutsch et al., 2019), which are traditionally used to measure IST related attentional bias. The IST proposes that sensitization of incentive salience can impact both conscious craving or wanting, as well as unconscious forms of motivation to seek drugs, which operate at a more implicit psychological level, even in the absence of intense craving feelings (Robinson et al., 2013). Despite the potential of the current approach (File et al., 2022), there is a need to investigate the relationship between the used measure and experimentally measured attentional bias, to better understand the relationship between explicit and implicit wanting. Moreover, despite the extensive literature on attentional bias related to dependence, the current study did not incorporate any behavioral measures to assess it. This inclusion would undoubtedly enhance the robustness of the present findings and contribute significantly to comprehending the connection between internal and external attention in the context of addictive behaviors. Additionally, the translation of items assessing the intention to quit and the personal relevance of smoking consequences into Hungarian may have potentially compromised the validity of these instruments. However, we followed a well-established translation and back-translation protocol (Beaton et al., 2000), reducing potential biases deriving from the translations. In addition, cross-sectional, self-report data were collected that might have introduced some biases (e.g., recall bias, under- or overreporting).

Conclusions

To the best of the authors’ knowledge, no previous research has examined the impact of addictive behavior on internal attention. The current findings suggest that the imbalance of wanting and liking—which is strongly associated with nicotine dependence—can relate to the personal relevance of smoking, a good indicator of internal attention. However, such attentional bias might not apply to all smokers to the same extent, which might contribute to the significant differences in past and current smoking behavior and in the intention to quit smoking. The findings also indicate that the bias of internal attention might play a significant role in both the initiation of smoking cessation, as well as in the likelihood of relapse. This suggests that including a more diverse array of topics in health communication could be beneficial, given the varying emphasis on smoking consequences among different profiles.

Data Availability

The data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

References

Adams, R. C., Sedgmond, J., Maizey, L., Chambers, C. D., & Lawrence, N. S. (2019). Food addiction: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of overeating. Nutrients, 11(9), 2086.

Amir, N., Beard, C., Taylor, C. T., Klumpp, H., Elias, J., Burns, M., & Chen, X. (2009). Attention training in individuals with generalized social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 77(5), 961.

Bar-Haim, Y., Lamy, D., Pergamin, L., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). Threat-related attentional bias in anxious and nonanxious individuals: A meta-analytic study. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 1–24.

Beaton, D. E., Bombardier, C., Guillemin, F., & Ferraz, M. B. (2000). Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine, 25(24), 3186–3191.

Beaudoin, C. E. (2002). Exploring antismoking ads: Appeals, themes, and consequences. Journal of Health Communication, 7, 123–137.

Berridge, K. C. (2009). ‘Liking’and ‘wanting’ food rewards: Brain substrates and roles in eating disorders. Physiology & Behavior, 97(5), 537–550.

Berridge, K. C., Robinson, T. E., & Aldridge, J. W. (2009). Dissecting components of reward: “liking”, “wanting”, and learning. Current Opinion in Pharmacology, 9(1), 65–73.

Bertoletti, M., Friel, N., & Rastelli, R. (2015). Choosing the number of clusters in a finite mixture model using an exact integrated completed likelihood criterion. Metron, 73, 177–199.

Bold, K. W., Toll, B. A., Cartmel, B., Ford, B. B., Rojewski, A. M., Gueorguieva, R., ..., & Fucito, L. M. (2018). Personalized intervention program: Tobacco treatment for patients at risk for lung cancer. Journal of Smoking Cessation, 13(4), 244–247.

Borland, R., Yong, H. H., Balmford, J., Cooper, J., Cummings, K. M., O'Connor, R. J., ..., & Fong, G. T. (2010). Motivational factors predict quit attempts but not maintenance of smoking cessation: Findings from the International Tobacco Control Four country project. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 12(suppl_1), S4-S11.

Bradley, B. P., Mogg, K., Wright, T., & Field, M. (2003). Attentional bias in drug dependence: Vigilance for cigarette-related cues in smokers. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 17(1), 66.

Brandon, T. H., & Baker, T. B. (1991). The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire: The subjective expected utility of smoking in college students. Psychological Assessment: A Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 3(3), 484.

Brosschot, J. F., Gerin, W., & Thayer, J. F. (2006). The perseverative cognition hypothesis: A review of worry, prolonged stress-related physiological activation, and health. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 60(2), 113–124.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Carter, B. L., & Tiffany, S. T. (1999). Meta-analysis of cue-reactivity in addiction research. Addiction, 94(3), 327–340.

Choi, J. S., Payne, T. J., Ma, J. Z., & Li, M. D. (2017). Relationship between personality traits and nicotine dependence in male and female smokers of African-American and European-American samples. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, 122.

Chun, M. M., Golomb, J. D., & Turk-Browne, N. B. (2011). A taxonomy of external and internal attention. Annual Review of Psychology, 62, 73–101.

Collins, L. M., & Lanza, S. T. (2009). Latent class and latent transition analysis: With applications in the social, behavioral, and health sciences (Vol. 718). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Copeland, A. L., Brandon, T. H., & Quinn, E. P. (1995). The Smoking Consequences Questionnaire-Adult: Measurement of smoking outcome expectancies of experienced smokers. Psychological Assessment, 7(4), 484.

Cowan, N. (2001). The magical number 4 in short-term memory: A reconsideration of mental storage capacity. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 24(1), 87–114.

Craik, F. I., & Lockhart, R. S. (1972). Levels of processing: A framework for memory research. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 11(6), 671–684.

Cribbie, R. A. (2000). Evaluating the importance of individual parameters in structural equation modeling: The need for type I error control. Personality and Individual Differences, 29(3), 567–577.

DiClemente, C. C., & Prochaska, J. O. (1998). Toward a comprehensive, transtheoretical model of change: Stages of change and addictive behaviors. In W. R. Miller & N. Heather (Eds.), Treating addictive behaviors (pp. 3–24). Plenum Press.

Etkin, A., & Wager, T. D. (2007). Functional neuroimaging of anxiety: A meta-analysis of emotional processing in PTSD, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobia. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 164(10), 1476–1488.

Field, M. (2005). Cannabis ‘dependence’and attentional bias for cannabis-related words. Behavioural Pharmacology, 16(5–6), 473–476.

Field, M., & Cox, W. M. (2008). Attentional bias in addictive behaviors: A review of its development, causes, and consequences. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 97(1–2), 1–20.

Field, M., Duka, T., Tyler, E., & Schoenmakers, T. (2009a). Attentional bias modification in tobacco smokers. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 11(7), 812–822.

Field, M., Munafò, M. R., & Franken, I. H. (2009b). A meta-analytic investigation of the relationship between attentional bias and subjective craving in substance abuse. Psychological Bulletin, 135(4), 589.

Field, M., Mogg, K., Mann, B., Bennett, G. A., & Bradley, B. P. (2010). Attentional biases in abstinent alcoholics and their association with craving. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(4), 522–528.

File, D., Bőthe, B., File, B., & Demetrovics, Z. (2022). The role of impulsivity and reward deficiency in “liking” and “wanting” of potentially problematic behaviors and substance uses. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 820836.

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Second Course, 10(6), 269–314.

Fishbein, M., Hall-Jamieson, K., Zimmer, E., von Haeften, I., & Nabi, R. (2002). Avoiding the boomerang: Testing the relative effectiveness of antidrug public service announcements before a national campaign. American Journal of Public Health, 92(2), 238–245.

Flora, D. B., & Curran, P. J. (2004). An empirical evaluation of alternative methods of estimation for confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data. Psychological Methods, 9(4), 466–491.

Franken, I. H. (2003). Drug craving and addiction: Integrating psychological and neuropsychopharmacological approaches. Progress in Neuro-Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry, 27(4), 563–579.

Goldstein, R. Z., Woicik, P. A., Moeller, S. J., Telang, F., Jayne, M., Wong, C., ..., & Volkow, N. D. (2010). Liking and wanting of drug and non-drug rewards in active cocaine users: The STRAP-R questionnaire. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 24(2), 257–266.

Gotlib, I. H., & Joormann, J. (2010). Cognition and depression: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 285–312.

Grigutsch, L. A., Lewe, G., Rothermund, K., & Koranyi, N. (2019). Implicit ‘wanting’ without implicit ‘liking’: A test of incentive-sensitization-theory in the context of smoking addiction using the wanting-implicit-association-test (W-IAT). Journal of Behavior Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 64, 9–14.

Heatherton, T. F., Kozlowski, L. T., Frecker, R. C., & Fagerstrom, K. O. (1991). The Fagerström test for nicotine dependence: A revision of the Fagerstrom Tolerance Questionnaire. British Journal of Addiction, 86(9), 1119–1127.

Hobbs, M., Remington, B., & Glautier, S. (2005). Dissociation of wanting and liking for alcohol in humans: A test of the incentive-sensitisation theory. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 178(4), 493–499.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55.

Ihssen, N., & Wadsley, M. (2021). A reward and incentive-sensitization perspective on compulsive use of social networking sites–wanting but not liking predicts checking frequency and problematic use behavior. Addictive Behaviors, 116, 106808.

Jha, P., Chaloupka, F. J., & Moore, J. (2006). Tobacco addiction In: Disease Control Priorities in the Developing Countries (2nd ed.). New York: Oxford University Press.

Joyner, M. A., Kim, S., & Gearhardt, A. N. (2017). Investigating an incentive-sensitization model of eating behavior: Impact of a simulated fast-food laboratory. Clinical Psychological Science, 5(6), 1014–1026.

Kavanagh, D. J., Andrade, J., & May, J. (2005). Imaginary relish and exquisite torture: The elaborated intrusion theory of desire. Psychological Review, 112(2), 446.

Kensinger, E. A., & Corkin, S. (2003). Memory enhancement for emotional words: Are emotional words more vividly remembered than neutral words? Memory & Cognition, 31(8), 1169–1180.

Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52–54.

Kline, R. B. (2016). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4th ed). New York: Guilford.

Lambert, N. M., McLeod, M., & Schenk, S. (2006). Subjective responses to initial experience with cocaine: An exploration of the incentive–sensitization theory of drug abuse. Addiction, 101(5), 713–725.

Leshner, G., Bolls, P., & Wise, K. (2011). Motivated processing of fear appeal and disgust images in televised anti-tobacco ads. Journal of Media Psychology, 23, 77–89.

Liu, S., Lane, S. D., Schmitz, J. M., Waters, A. J., Cunningham, K. A., & Moeller, F. G. (2011). Relationship between attentional bias to cocaine-related stimuli and impulsivity in cocaine-dependent subjects. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 37(2), 117–122.

Luck, S. J., & Gold, J. M. (2008). The construct of attention in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 64(1), 34–39.

Marsh, H., Hau, K., & Grayson, D. (2005). Goodness of fit in structural equation models. In A. Maydeu-Olivares & J. McArdle (Eds.), Multivariate applications book series. Contemporary psychometrics: A festschrift for Roderick P. McDonald (pp. 275–340). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

McKee, S. A., Sinha, R., Weinberger, A. H., Sofuoglu, M., Harrison, E. L., Lavery, M., & Wanzer, J. (2011). Stress decreases the ability to resist smoking and potentiates smoking intensity and reward. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 25(4), 490–502.

McLaughlin, K. A., & Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2011). Rumination as a transdiagnostic factor in depression and anxiety. Behavior Research and Therapy, 49(3), 186–193.

Murray, S. O., & Wojciulik, E. (2004). Attention increases neural selectivity in the human lateral occipital complex. Nature Neuroscience, 7, 70–74.

Narhi-Martinez, W., Dube, B., & Golomb, J. D. (2023). Attention as a multi-level system of weights and balances. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Cognitive Science, 14(1), e1633.

Nikolaidou, M., Fraser, D. S., & Hinvest, N. (2019). Attentional bias in Internet users with problematic use of social networking sites. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 8(4), 733–742.

Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(4), 535–569.

Ostafin, B. D., Marlatt, G. A., & Troop-Gordon, W. (2010). Testing the incentive-sensitization theory with at-risk drinkers: Wanting, liking, and alcohol consumption. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 24(1), 157–162.

Pessoa, L. (2019). Understanding emotion with brain networks. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, 28, 17–25.

Petersen, S. E., & Posner, M. I. (2012). The attention system of the human brain: 20 years after. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 35, 73–89.

Posner, M. I., & Petersen, S. E. (1990). The attention system of the human brain. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 13, 25–42.

Rinck, M., Becker, E. S., Kellermann, J., & Roth, W. T. (2005). Psychophysiological evidence for a motivational schema in addictive behavior. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 180(3), 470–477.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (1993). The neural basis of drug craving: An incentive-sensitization theory of addiction. Brain Research Reviews, 18(3), 247–291.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2000). The psychology and neurobiology of addiction: An incentive–sensitization view. Addiction, 95(8s2), 91–117.

Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2001). Incentive-sensitization and addiction. Addiction, 96(1), 103–114.

Robinson, M. J., Robinson, T. E., & Berridge, K. C. (2013). Incentive salience and the transition to addiction. Biological Research on Addiction, 2, 391–399.

Ruiter, R. A. C., Kessels, L. T. E., Peters, G.-J.Y., & Kok, G. (2014). Sixty years of fear appeal research: Current state of the evidence. International Journal of Psychology, 49, 63–70.

Stanaway, R. G., & Watson, D. W. (1980). Smoking motivation: A factor-analytical study. Personality and Individual Differences, 1(4), 371–380.

Sui, J., & Gu, X. (2017). Self as object: Emerging trends in self-research. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 97–148.

Sullivan, P. F., & Kendler, K. S. (1999). The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research, 1(Suppl_2), S51–S57.

Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 371–394.

Townshend, J., & Duka, T. (2001). Attentional bias associated with alcohol cues: Differences between heavy and occasional social drinkers. Psychopharmacology (Berl), 157, 67–74.

Turner, L. R., & Mermelstein, R. (2004). Motivation and reasons to quit: Predictive validity among adolescent smokers. American Journal of Health Behavior, 28(6), 542–550.

Urbán, R., Kugler, G., & Szilágyi, Z. (2004). A nikotindependencia mérése és korrelátumai magyar felnőtt mintában. Addiktológia, 3(3), 331–356.

Vangeli, E., & West, R. (2008). Sociodemographic differences in triggers to quit smoking: Findings from a national survey. Tobacco Control, 17(6), 410–415.

Vogel, E. K., McCollough, A. W., & Machizawa, M. G. (2005). Neural measures reveal individual differences in controlling access to working memory. Nature, 438(7067), 500–503.

Yang-Wallentin, F., Jöreskog, K. G., & Luo, H. (2010). Confirmatory factor analysis of ordinal variables with misspecified models. Structural Equation Modeling, 17(3), 392–423.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Eötvös Loránd University. The study was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (K126835, K131635). FD was supported by the National Research, Development and Innovation Office (PD138976).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

DF: conceptualization, methodology, visualization, writing, and analysis. BB: conceptualization, review, and editing. ZD: conceptualization, supervision, review, and editing.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of Interest

ELTE Eötvös Loránd University receives funding from the Szerencsejáték Ltd. to maintain a telephone helpline service for problematic gambling. ZD has also been involved in research on responsible gambling funded by Szerencsejáték Ltd. and the Gambling Supervision Board and provided educational materials for the Szerencsejáték Ltd’s responsible gambling program. The University of Gibraltar receives funding from the Gibraltar Gambling Care Foundation. These funding sources are not related to the present study, and the funding institution had no role in the study design or the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, writing the manuscript, or the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendices

Appendix 1 Personal relevance of smoking consequences. Participants were asked to indicate the importance of each consequence using a 5-point Likert scale, ranging from 1–not at all to 5–very important. + : positive consequence; − : negative consequence

-

a.

Helps me connect with others ( +)

-

b.

Unhealthy ( −)

-

c.

I like rituals related to smoking ( +)

-

d.

Costs a lot of money ( −)

-

e.

Helps me to concentrate ( +)

-

f.

Does not fit in with the lifestyle I want ( −)

-

g.

Makes me feel guilty ( −)

-

h.

Disturbs my environment ( −)

-

i.

It brings greater fulfillment to my life ( +)

-

j.

Helps me manage stress ( +)

-

k.

It makes me less fit ( −)

-

l.

It negatively affects my appearance ( −)

-

m.

It aids in overcoming cravings ( +)

-

n.

Helps me keep my weight at the right level ( +)

Appendix 2 Bonferroni adjusted p values of pairwise Wilcoxon tests when comparing the three profiles

Sex | |||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | ||||

Cost-focused | 0.15 | ||||

Gain-focused | 0.63 | 0.23 | |||

Age | Certainty about quitting | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | 0.04 | Cost-focused | < 0.001 | ||

Gain-focused | < 0.001 | 0.05 | Gain-focused | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Income | Planned time of quitting | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | 0.32 | Cost-focused | < 0.001 | ||

Gain-focused | 0.23 | 0.60 | Gain-focused | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

Nicotine dependence | Importance of quitting | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | 0.34 | Cost-focused | < 0.001 | ||

Gain-focused | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | Gain-focused | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

No. of cigarettes per day | WmL before | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | 0.32 | Cost-focused | < 0.001 | ||

Gain-focused | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | Gain-focused | < 0.001 | 0.16 |

Years of smoking | WmL during | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | 0.08 | Cost-focused | 0.37 | ||

Gain-focused | 0.36 | 0.03 | Gain-focused | 0.23 | 0.46 |

Regret about smoking | WmL after | ||||

Neutral | Cost-focused | Neutral | Cost-focused | ||

Cost-focused | < 0.001 | Cost-focused | < 0.001 | ||

Gain-focused | 0.66 | < 0.001 | Gain-focused | < 0.001 | 0.59 |

Quit attempt in the past 12 months (% Yes) | ||

Neutral | Cost-focused | |

Cost-focused | 0.0022 | |

Benefit-focused | 0.0022 | < 0.001 |

Appendix 3 Summary table of Kruskal–Wallis test results comparing the three smoker profiles among personal relevance

Kruskal–Wallis H | df | p | η2 | Neutral (1) | Cost-focused (2) | Gain-focused (3) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Social connection (P) | 9.3822 | 2 | 0.009 | 0.00897 | 2.39 (1.37) | 2.64 (1.16) | 2.62 (1.22) |

Habit (P) | 34.894 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.0400 | 3.72 (1.29)3 | 3.85 (0.84)3 | 4.28 (0.78)1,2 |

Focus (P) | 176.1 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.212 | 2.46 (1.35)2,3 | 3.04 (1.11)1,3 | 3.98 (0.81)1,2 |

Fulfill life (P) | 120.07 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.143 | 2.31 (1.30)2,3 | 2.56 (1.05)1,3 | 3.45 (0.99)1,2 |

Cope stress (P) | 66.544 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.0784 | 3.27 (1.43)3 | 3.40 (1.04)3 | 4.14 (0.80)1,2 |

Craving reduction (P) | 41.12 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.0475 | 3.26 (1.48)2,3 | 3.80 (1.03)1 | 4.07 (0.98)1 |

Weight management (P) | 52.847 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.0618 | 2.28 (1.48)2,3 | 2.94 (1.19)1 | 2.94 (1.24)1 |

Unhealthy (N) | 89.13 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.106 | 3.64 (1.40)2,3 | 4.29 (0.90)1,3 | 3.33 (1.07)1,2 |

Financial aspects (N) | 79.446 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.0941 | 3.32 (1.42)2 | 4.17 (0.95)1,3 | 3.36 (1.09)2 |

Desired lifestyle (N) | 311.18 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.376 | 2.61 (1.35)2,3 | 4.01 (0.83)1,3 | 2.03 (0.78)1,2 |

Guilt (N) | 301.66 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.364 | 2.68 (1.49)2,3 | 4.07 (0.83)1,3 | 1.87 (0.87)1,2 |

Social conflicts (N) | 112.93 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.135 | 2.84 (1.39)2 | 3.84 (0.93)1,3 | 2.87 (1.02)2 |

Fitness (N) | 179.21 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.215 | 3.09 (1.45)2,3 | 4.05 (0.85)1,3 | 2.61 (0.90)1,2 |

Appearance (N) | 160.83 | 2 | p < 0.001 | 0.193 | 2.84 (1.42)2 | 3.91 (0.89)1,3 | 2.61 (0.97)2 |

Appendix 4 Best model solutions for Gaussian finite mixture model fitted by EM algorithm

Classes | BIC | ICL |

|---|---|---|

2 | − 30,043.83 | − 30,354.57 |

3 | − 30,032.47 | − 30,388.13 |

4 | − 29,961.59 | − 30,236.2 |

5 | − 30,016.63 | − 30,345.24 |

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

File, D., Bőthe, B. & Demetrovics, Z. The Imbalance of Wanting and Liking Contributes to a Bias of Internal Attention Towards Positive Consequences of Tobacco Smoking. Int J Ment Health Addiction (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01179-8

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-023-01179-8