Abstract

This study aims to propose a clarification on how female entrepreneurs cognitively process their work-family conflict (WFC) experiences during the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, with implications related to their attitudes toward their current entrepreneurial activities. It does so by using social cognitive theory as an overarching theoretical perspective. Our hypothesis sheds light on regretful thinking (also known as entrepreneurial regret) as a cognitive mechanism that elucidates how WFC may affect female entrepreneurs’ outcomes, such as exit intention and work satisfaction. We further proposed family support as a boundary condition that may help female entrepreneurs to better respond to WFC. We develop and administer a questionnaire survey and analyze data from 346 female entrepreneurs in Japan. The results of our analysis, which is performed using the bootstrapping method to clarify the significance of the moderated mediation mechanism, support our hypotheses. Our results demonstrate that WFC leads to higher exit intention and lower work satisfaction through entrepreneurial regret. Notably, these experiences become stronger when WFC is coupled with low family support. Finally, we discuss the important implications of our findings for researchers and practitioners and highlight opportunities for future research.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

The work-family conflict (WFC) phenomenon has long been regarded as a major obstacle to female entrepreneurs in the venture development process (Gherardi, 2015; Thébaud, 2015). WFC is “a form of inter-role conflict in which role pressures from the work and family domains are mutually incompatible in some respect” (Greenhaus & Beutell, 1985, p. 77). Compared to their male counterparts, female entrepreneurs face more pronounced dual pressures from work responsibilities and household duties (Greenhaus & Parasuraman, 1999), which can be attributed to gender stereotypes (Liñán et al., 2020). In other words, societal expectations concerning how men and women should behave are prominent, which emanate from past observations of the roles typically performed by men (e.g., a breadwinner of the family) and women (e.g., a housewife) in the past (Eagly, 1987). Even among dual career couples, research revealed that men continue to expect women to fulfill family roles, such as household chores and childcare, while continuing to earn for the family (Shockley & Allen, 2018). Ahl (2006, p. 605) notes that: “giving the woman’s double responsibilities – work and family – she cannot compete on equal terms with a man in the same line of business.” Female entrepreneurs are, therefore, disadvantaged owing to liabilities, such as the smallness and newness of their venture, and being women; this limits their opportunities to access and leverage key entrepreneurial resources (Jennings & Brush, 2013; Jennings & McDougald, 2007).

Prior research has documented the prevalence of traditional gender-role stereotypes in many cultures where women are expected to act first as caregivers, nurturers, and mothers to their families, while men are expected to fulfill their role as breadwinners (Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Martins et al., 2002). Unfortunately, this trend is prevalent in modern societies (Cerrato & Cifre, 2018; Singh et al., 2018). In Japan, gender role expectations that impose informal constraints on women and their behaviors continue to exist in a patriarchal society (Futagami & Helms, 2009). For instance, Japanese women are expected to retain the traditional “good wife and wise mother” role ideology (known as ryōsai-kenbo), which has caused a social stigma attached to working women such as female entrepreneurs (Araújo Nocedo, 2012; Bobrowska & Conrad, 2017; Leung et al., 2014). Women who fail to conform to this societal expectation can be judged harshly. Traditional gender role expectations that continue to be pervasive in Japan may further explain the low level of women’s participation in entrepreneurial activities. Indeed, Japan’s total early-stage entrepreneurial activity (TEA) ratio for women has been considerably low, accounting for only 4%. This is much lower compared to their Western counterparts, such as Canada (15.8%), the United States (15.2%), and the United Kingdom (10.9%) (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2021/2022 Global Report). Thus, Japanese society tends to hold conservative beliefs toward women’s entrepreneurship.

Existing research consistently demonstrates the detrimental impact of WFC on entrepreneurs’ attitudes, behaviors, and well-being, including job satisfaction (De Clercq et al., 2021a; Schjoedt, 2021), exit intention (Hsu et al., 2016), and work tension (Carr et al., 2015). However, while there are numerous well-developed WFC-related conceptual studies that address female entrepreneurship (e.g., Jennings & McDougald, 2007; Shelton, 2006), empirical efforts to identify and empirically examine cognitive mechanisms that could explain “how” female entrepreneurs shape their thinking around work’s interference with family, which often adversely affects work outcomes, are lacking. This is meaningful, as people do not necessarily react instantly or spontaneously to outside pressures. Concerning entrepreneurship, some thought certainly precedes decisions on whether to pursue a particular course of action (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998).

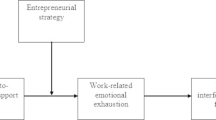

This study draws on social cognitive theory (SCT: Bandura, 1989) as an overarching theoretical perspective to elucidate the cognitive process that underlies female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences. SCT (Bandura, 1986) states that there are certain basic human capabilities that people can utilize when initiating a certain course of action, such as entrepreneurship. For instance, people may utilize their forethought capability to plan future behavioral responses (i.e., what I am going to do) and determine the likely consequences (i.e., what I am going to get for it) of engaging in those actions or behaviors (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Similarly, female entrepreneurs experiencing WFC may experience regretful thinking, described as thoughts regarding situations and outcomes that do not meet initial expectations (Roese, 1997; Zeelenberg et al., 1998) and that could adversely affect their attitudes toward their current entrepreneurial path, including work satisfaction and heightening the possibility of exit intention. We acknowledge that not everyone who encounters WFC will necessarily engage in regretful thinking. While the broader society may pose certain gender role expectations for individuals to conform to, the closer surrounding environment, such as family members, may promote women’s liberation and personal life choices. Therefore, we posit family support as a positive enabling force for female entrepreneurs that counter the tendency of regretful thinking. Indeed, existing empirical findings confirm how family support plays a significant role in attenuating an individual’s WFC experiences (Xu et al., 2020). In summary, this study proposes and empirically analyzes the conceptual framework as visually presented in Fig. 1.

This study contributes to the current stream of research on female entrepreneurship and WFC in meaningful ways. First, we elucidate the significant impact of female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic on attitudes toward their entrepreneurial initiatives, through the cognitive mechanism of entrepreneurial regret. By examining the impact of WFC from a social cognitive perspective (Bandura, 1989), we acknowledge that people are not passive actors influenced by external environments. Contrarily, they have the ability to engage actively in a thought process that leads them to gain a more critical and constructive understanding of their reality. This, in turn, can be used to inform their decision about committing to their current entrepreneurial path. Second, we incorporate family support as a boundary condition that can explain the variation in the relationship between WFC and female entrepreneurs’ work outcomes. Thereby, we respond to a recent call for this type of study (e.g., De Clercq et al., 2021b; Hsu et al., 2019) and address empirical inconsistencies around the relationship between WFC and female entrepreneurs’ work outcomes (Welsh & Kaciak, 2018).

Finally, our research context is particularly important for understanding female entrepreneurs’ difficult experiences concerning WFC in Japan. The contemporary Japanese society is deeply patriarchal; thus, women continue to experience gender-role stereotypes that hinder them from accessing resources and achieving growth opportunities (Futagami & Helms, 2009). Faced with societal pressures to perform their gendered roles in fulfilling family obligations, many Japanese female entrepreneurs encounter numerous difficulties in managing their own entrepreneurial activities (Welsh et al., 2014). Even though the government attempts to promote female entrepreneurship without disrupting gender expectations at home, society deems female entrepreneurship an impediment to women’s performance in their family roles as mothers and caregivers (Bobrowska & Conrad, 2017).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. First, we provide a brief overview of female entrepreneurs during the COVID-19 crisis as our research setting, following which we introduce our theoretical lens and formulate a set of relevant hypotheses. This is followed by details of data and the operationalization of our variables used in this research. Next, we present the empirical results of our bootstrap analyses. The final section concludes the study by offering major theoretical and practical implications and potential opportunities for future research.

Background

Negative impacts of the COVID-19 crisis on female entrepreneurs

Ongoing challenges concerning the COVID-19 pandemic have negatively affected female entrepreneurs. Referring to a recent survey by the Diana International Research Institute, Manolova et al. (2020) documented that 67.4% of female entrepreneurs experienced a significant drop in revenue. In the United Kingdom, female entrepreneurs were impacted more negatively than male entrepreneurs were, with 72% experiencing a loss in trade volume (Stephan et al., 2020). In Germany, 63% of female entrepreneurs reported income losses compared to 47% among their male counterparts (Graeber et al., 2021). Graeber et al.’s (2021) study also reveals that 54% of female entrepreneurs (versus 46% of males) reduced their working hours during the pandemic. From these sources, it is clear that the adverse impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has been distressing to female entrepreneurs (Manolova et al., 2020). Female entrepreneurs also experienced the pressures of both work and family roles simultaneously.

Women typically face greater challenges in managing daily work-family demands. The pandemic and social distancing measures implemented by governments globally forced women to take on more unpaid domestic responsibilities, such as childcare and homeschooling owing to unplanned school closures (kindergarten and nursery) (Ayatakshi-Endow et al., 2021; Grandy et al., 2020). Extant research argues that female entrepreneurs are more susceptible to economic crises, such as pandemics, as most start and run micro and small businesses (Jaim, 2021). Compared to their male counterparts, female entrepreneurs often suffer from a lack of funding options, technical means, network connections, and institutional support for their businesses (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, 2021). Additionally, female entrepreneurs are most likely to run and manage business activities in the retail and service industries, most of which have been under severe economic pressure due to the pandemic (Rigoni et al., 2021). These industries are known for their low barriers to entry and ruthless competition, both of which make it harder for female entrepreneurs to adjust their business models (Manolova et al., 2020). As female entrepreneurs are generally financially weaker and less capable of adapting their business activities to a crisis, the COVID-19 pandemic has further worsened the entrepreneurial gender gap worldwide (OECD, 2021). Without the ability to capitalize on knowledge from past crisis experiences, the unprecedented economic disruption caused by the pandemic posed a daunting challenge to female entrepreneurs (Afshan et al., 2021).

Theory and hypotheses development

Work family conflict, entrepreneurial regret and outcomes

This study draws on SCT (Bandura, 1989) as an overarching theoretical clarification of the cognitive mechanisms underlying female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences and explores its implications for their satisfaction as well as their commitment to continue their entrepreneurial paths. According to SCT, “people function as anticipative, purposive, and self-evaluating proactive regulators of their motivation and actions” (Bandura & Locke, 2003, p. 87). Specific basic human capabilities inform decision-making processes regarding whether to pursue and/or persist in a particular behavior or activity. For example, people may utilize their forethought capability that enables them to plan their courses of action (i.e., what I am going to do) based on their anticipation of the likely consequences of engaging in a specific behavior (i.e., “what I am going to get for it?”) (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Simply put, people carefully determine and weigh both the positive and negative outcomes that may occur when they perform a specific action. In this vein, we argue that, due to their WFC experiences, female entrepreneurs may utilize their forethought capability to evaluate the advantages and disadvantages associated with their entrepreneurship. This evaluation may be demonstrated through regretful thinking, which involves some thoughts about business situations and entrepreneurial outcomes that may not go as expected, thereby resulting in attitudinal (such as work satisfaction) as well as behavioral reactions (such as the decision to either continue or discontinue their entrepreneurial journey).

WFC becomes a factor when work demands and family roles become incompatible. It often results in women’s participation in one role becoming more challenging, as they simultaneously attend to another role (Greenhaus & Parasuraman, 1999; Hughes et al., 2012). To effectively manage both their work and family demands, female entrepreneurs must carefully plan what proportions of their time they will allot to entrepreneurial and familial activities, respectively (Poggesi et al., 2019). This tendency is consistent with the SCT-based argument that people do not react immediately to their environments. Instead, they employ their forethought capability to cognitively plan what they are going to do based on their subjective evaluation of what is going to happen (Bandura, 1989; Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Given the societal pressure to be successful both at work and at home, we argue that female entrepreneurs are likely to engage in regretful thinking.

Entrepreneurial regret or regretful thinking refers to thoughts that stem from the disappointments, frustrations, and feelings of unhappiness produced by a failure to achieve their desired entrepreneurial objectives (Roese, 1997; Zeelenberg et al., 1998). This mode of thinking can be described as “imagining ‘what might have been’ in a given situation, reflecting on outcomes and events that might have occurred if the person in question had acted differently or if circumstances had somehow been different” (Baron, 2000, p. 79). “Imagining ‘what might have been’ in a given situation” is closely aligned with the forethought capability posited by SCT (Bandura, 1989), which involves anticipating both positive and negative consequences that are likely to emanate from performing a specific behavior (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Following the SCT perspective, we therefore argue that when female entrepreneurs engage in regretful thinking, they utilize their forethought capability to evaluate the probable outcomes and events that may occur if they decide to either continue or discontinue their entrepreneurial activities. Specifically, entrepreneurial regret occurs when individuals foresee more negatives than positives associated with their current entrepreneurial path.

Entrepreneurial regret has been found to be a serious concern for many entrepreneurs. According to Hsu et al. (2019), 40% of the sampled entrepreneurs reported that they regretted engaging in an entrepreneurial endeavor. Considering female entrepreneurs in particular, their regrets are often related to unmet expectations in terms of the nature of entrepreneurial activities: long work hours, irregular incomes, and challenges in managing work and family demands (Hsu et al., 2019). When experiencing entrepreneurial regret, individuals imagine or anticipate the possible outcomes from pursuing their entrepreneurial journey. Unfortunately, these anticipated outcomes are largely negative, leading to a feeling of regret (Khanin et al., 2021). Due to the need to manage both work responsibilities and family obligations simultaneously, female entrepreneurs may experience negative emotions, such as disappointment, frustration or intense regret. Such negative thoughts and feelings subsequently undermine their perseverance to continue their entrepreneurship (Markman et al., 2005), resulting in higher intentions to exit from their entrepreneurial path and lower levels of work satisfaction.

In summary, we argue that female entrepreneurs are particularly prone to experiencing the pressure of having to meet both work responsibilities and family obligations. Exposure to WFC causes them to carefully weigh their decision to either pursue or discontinue their entrepreneurial activities to enable a better work-family balance. Specifically, they do so through entrepreneurial regret, a process by which they are more likely to anticipate negative outcomes. Hence, entrepreneurial regret accounts for how WFC experiences influences female entrepreneurs’ decision to discontinue operating their business ventures (i.e., exit intention) and their attitudes toward their existing entrepreneurial journey (i.e., work satisfaction). Drawing on these lines of argument, the following hypotheses are proposed:

Hypothesis 1(a)

Entrepreneurial regret positively mediates the effect of WFC on exit intention.

Hypothesis 1(b)

Entrepreneurial regret negatively mediates the effect of WFC on work satisfaction.

Moderating role of family support

Family is well-acknowledged as one of the most crucial relational sources of social support (Edelman et al., 2016; Xu et al., 2020). Family is particularly meaningful for entrepreneurs as it provides them with “a security blanket” when they encounter pressing financial issues (Powell & Eddleston, 2013, p. 265). In the context of female entrepreneurship, family support refers to the extent to which women’s well-being and business success are given high priority and supported by their family members (Jennings & Brush, 2013; Jennings & McDougald, 2007). Family support represents key interpersonal assistance that individual members share and mobilize reciprocally to facilitate achieving their goals (Edelman et al., 2016; Gudmunson et al., 2009). Furthermore, family support plays an essential role in female entrepreneurs’ dedication to achieving entrepreneurial success, fulfilling their desire for personal enjoyment, and managing work-family balance. This is because it ensures they maintain emotional stability while operating their ventures (Eddleston & Powell, 2012). Due to family support’s significant role, in this study, we treat it as an important positive force that female entrepreneurs need when managing WFC.

In an extension of Aldrich and Cliff’s (2003) family embeddedness perspective, family support is key to female entrepreneurs’ business operations for various reasons. First, as women’s entrepreneurship is broadly viewed as less important than men’s, female entrepreneurs are likely to struggle more with limited access to critical resources needed for exploring new business opportunities (e.g., financial, social, and human capital) (Mari et al., 2016; Vershinina et al., 2020; Welsh et al., 2014). Furthermore, they tend to suffer from lower levels of work schedule autonomy and flexibility (Jennings & McDougald, 2007) when managing their own ventures. Social support from women’s family members may therefore serve as a vital resource that can have a significant impact on their business success (Hsu et al., 2016; Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Family support includes providing reliable strategic information (Mari et al., 2016), family financial capital (Bird & Wennberg, 2016), family social capital (Chang et al., 2009; Edelman et al., 2016), and family emotional support (Welsh et al., 2014, 2016). Furthermore, because they are faced with gender role segregation, particularly in collectivist societies such as Japan, female entrepreneurs, unlike their male counterparts, are constantly under pressure to manage family obligations. Women invest a significant amount of time, attention, and energy juggling multiple household duties, such as conforming to the societal definition of housewives, mothers, caregivers, and nurturers, all at once (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). As their family and work responsibilities are much more closely intertwined, female entrepreneurs may be required to care more about work-family synergies than their male counterparts, who enjoy more independence and autonomy (Powell & Eddleston, 2013). Therefore, support from family members, which can be in the form of tangible and/or intangible resources, may enable female entrepreneurs to accomplish balance between work and family at all phases of venture development (Welsh et al., 2014). We follow Shelton (2006) in using the term supportive family members to refer to individuals who proactively engage in taking on additional household duties to encourage female entrepreneurs to focus on their business activities.

In SCT considerations (Bandura, 1989), we argue that when female entrepreneurs encounter WFC (i.e., the predictor), family support (i.e., the first-stage boundary condition) may help alleviate their entrepreneurial regret (i.e., the mediating mechanism), thereby weakening their exit intention and enhancing their work satisfaction (i.e., outcomes). Family support could provide female entrepreneurs with important resources, such as information, as well as affective, financial and social support, which they can utilize during all phases of their venture development (Mari et al., 2016; Welsh et al., 2016, 2021). Thus, when they envision the possible consequences of their entrepreneurial activities, they may form a belief that they can effectively run their business ventures despite the pressure of being required to meet work-family demands. Conversely, if female entrepreneurs receive limited family support, it may intensify their entrepreneurial regret when they encounter WFC, further strengthening their exit intention and reducing their work satisfaction. Using their forethought related to the probable outcomes of their entrepreneurial initiatives, they will likely foresee more disadvantages associated with operating their business ventures (Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). Based on these arguments, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2(a)

At the first-stage moderation, the positive mediating relationship between WFC, entrepreneurial regret, and exit intention becomes stronger (weaker) at low (high) levels of family support.

Hypothesis 2(b)

At the first-stage moderation, the negative mediating relationship between WFC, entrepreneurial regret, and work satisfaction becomes stronger (weaker) at low (high) levels of family support.

Methodology

Sample and procedures

This study utilized data from female entrepreneurs actively operating ventures in Japan. We collaborated with Macromill Ltd., an online market research company, to get in touch with female entrepreneurs and distribute online questionnaire surveys to potential participants. We implemented several important steps when developing the questionnaire surveys. First, as English is not the native language in Japan, we followed Brislin’s (1970) recommendation and adopted a back-translation approach. The questionnaire was prepared in English and then translated into Japanese by a professional translation agency. It was then carefully back-translated into English by a Japanese academic who was highly proficient in both languages. This was done to ensure consistency, accuracy, and clarity across the translated items. Furthermore, to alleviate the possible common method variance (CMV) that could potentially result from self-reported responses, we used various remedies suggested by Podsakoff et al., (2003), such as randomizing item ordering and reverse-coding some items. Importantly, upon completing the questionnaire development, we conducted a pilot study involving five female entrepreneurs. Their feedback was carefully considered to refine the validity and accuracy of our survey items before launching the final version of the questionnaire. Following Podsakoff and Organ (1986), we performed a Harman’s (1967) one-factor test to check for CMV. According to the result of this statistical technique, the proportion of variance explained by the first factor was only 29.3% was below the generally accepted threshold of 50%. Moreover, we adopted Lindell and Whitney’s (2001) marker variable method to control for CMV. Information and communication technology (ICT) use was used as our marker variable as it should not be theoretically related to the main constructs (i.e., work-life conflict, entrepreneurial regret, exit intentions and work satisfaction) in our framework for analysis. Following the work of Saridakis et al. (2018), ICT use was measured by the value of 1 if a participant’s business had a social media profile. The findings of our study confirmed no statistically significant correlations between the marker variable and our principal variables. No substantial changes were observed before and after controlling for the marker variable. Considering the thorough execution of our ex-ante and ex-post steps to rule out the issue of CMV, we conclude that CMV is unlikely to undermine the validity of the findings of this study.

We administered the questionnaire by distributing the survey link to a total of 1,631 female entrepreneurs. We received 618 complete responses, achieving a response rate of 37.9%. Among the 618 responses obtained, we narrowed down the sample by exclusively focusing on married female entrepreneurs. The major rationale for this is that business and family demands are more inclined to influence entrepreneurial outcomes (Hsu et al., 2016). This produced a sample of 346 responses, yielding a valid response rate of 21.2%. Our survey response rate was reasonably high as this response quality was consistent with previous studies on female entrepreneurs’ behaviors and entrepreneurial decision-making (e.g., Collins-Dodd et al., 2004; Mari et al., 2016; Prasad et al., 2013). As presented in Table 1, among the participants in the final sample, the majority was aged between 30 and 49 years (69.95%), were novice entrepreneurs (95.09%), and more than half had at least one child was a minor (54.62%). Interestingly, most participating married female entrepreneurs had educational qualifications below a bachelor’s degree (65.05%). Finding a work-life balance was the most crucial motive for launching businesses for most respondents (87.28%). With respect to other entrepreneurial motives, many respondents also reported that their desire to develop business skills (58.09%) was central to making the decision to operate their own business. These descriptive statistics are congruent with prior research on female entrepreneurs, and reveal that women are significantly different from their male counterparts, whose objective to earn a higher income is a major entrepreneurial motive (Hsu et al., 2019).

Measures

We asked participants to evaluate the individual items using a 7-point Likert scale ranging from (1) = “strongly disagree” to (7) = “strongly agree.”

Work-family conflict (WFC)

The respondents were asked to assess their WFC experience during the COVID-19 pandemic using a 5-item measure adapted from prior studies (e.g., Netemeyer et al., 1996). Sample items include “the demands of my work interfere with my home and family life during this pandemic,” “the amount of time my work takes up makes it difficult to fulfill family responsibilities during this pandemic,” and “my work does not produce a strain that makes it difficult to fulfill family duties during this pandemic” (reverse statement). The scale yielded a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.92, indicating acceptable reliability.

Family support

We asked the respondents to rate the level of perceived family support using a 4-item measure modified by Powell and Eddleston (2013) in an extension of King et al.’s (1995) original measure of employees’ perceived family social support. Sample items were “family members often go above and beyond what is normally expected to help my business succeed” and “family members often contribute to my business without expecting to be paid.” The scale yielded a reliability coefficient of 0.84.

Entrepreneurial regret

We measured female entrepreneurial regret using two major questions sourced from previous studies (e.g., Hsu et al., 2019). The first question was related to the degree of feeling regretful: Knowing what you know now, if you had to decide all over again whether to enter the same line of work you are now in, what would you decide? We asked the respondents to choose one of the following statement options, including (1) “I would decide without any hesitation to take the same work,” (2) “I would have some second thoughts,” or (3) “I would definitely decide not to take the same work.” The second question was related to the extent to which they would recommend the same career path (i.e., entrepreneurship) to others: If a good friend of yours told you that he or she was interested in working in work like yours, what would you tell your friend? The respondents were asked to choose one of the following statement options: (1) “I would strongly recommend my work,” (2) “I would have doubts about recommending it,” or (3) “I would strongly advise my friend against working in a work like mine.” We averaged these scores into a composite measure. The average value of entrepreneurial regret was 1.777 and the standard deviation was 0.442. The entrepreneurial regret construct is made up of two items; therefore, methodology experts emphasize on the inadequacy of Cronbach’s alpha as an indicator for verifying an acceptable level of scale reliability, as emphasized by methodology experts (Cortina, 1993; Nunnally, 1978). To ensure the measurement’s composite reliability, we conducted a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA), in accordance with prior research in the field of entrepreneurship (e.g., Eddleston & Powell, 2012; Powell & Eddleston, 2013, 2017). The details of the CFA results are presented at the end of this section.Footnote 1

Exit intention

Using a 4-item scale originally developed by Fried et al. (1996), the respondents reported the extent to which they experienced the intention to exit their current entrepreneurial path. Sample items include “If I have my own way, I will leave to work in another organization one year from now” and “I frequently think of quitting this work.” The score for the Cronbach’s alpha of this measure is 0.80, suggesting good internal reliability.

Work satisfaction

The respondents reported their satisfaction with their current entrepreneurial path using a three-item scale developed by Cammann et al. (1983). Sample items are “In general, I like working at my current organization” and “In general, I do not like my job” (reverse coded). The Cronbach’s alpha of this measure is 0.71.

Control variables

We controlled for some other factors that could affect our dependent variables by following previous research on female entrepreneurship (e.g., De Clercq et al., 2021b; Liu et al., 2019; Mari et al., 2016; Wijewardena et al., 2020). First, we controlled for respondents’ age, measured in number of years. Consistent with previous studies (Manolova et al., 2007; Welsh et al., 2014), we measured the level of respondent’s educational attainment based on an ordinal scale (1 = junior high school diploma; 2 = high school diploma; 3 = professional training college diploma; 4 = junior college diploma; 5 = bachelor’s degree; 6 = master’s degree; 7 = doctorate). Additionally, we included the amount of prior entrepreneurial experience to control for the potential effect of female entrepreneurs’ associated experiential knowledge of the female entrepreneurs. Specifically, respondents reported how many ventures they had established and managed before operating their current venture. Finally, respondents were asked to indicate the number of children (minor) living with them. This variable was vital; the number of dependents indicates the types of family obligations and responsibilities respondents must attend.

As mentioned earlier, we performed CFA to confirm the measurement model and the dimensionality and validity of the five constructs (i.e., WFC, entrepreneurial regret, family support, entrepreneurial exit intention, and work satisfaction), using STATA Version 12 software. Results indicated that the five variables of interest in this study are distinct from each other. The chi-square statistic for this model indicates high statistical significance (\({\chi }^{2}\) = 236.547, p-value = 0.000). The other goodness-of-fit statistics were also acceptable (comparative fit index [CFI] = 0.96, Tucker-Lewis index [TLI] = 0.95, root mean square error of approximation [RMSEA] = 0.05, and standardized root mean squared residual [SRMR] = 0.05).

Results

Preliminary results

The descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations), zero-order correlations, and reliability estimates are reported in Table 2. The main variables (i.e., WFC, entrepreneurial regret, family support, exit intention and work satisfaction) all exhibited acceptable reliabilities, with reliability coefficients of at least 0.70 (Kline, 1999; Nunnally, 1978). Furthermore, none of the correlation coefficients exceeded the threshold value of 0.70 (Tabachnick et al., 2007), indicating that our estimations are unlikely to suffer from multicollinearity issues. To ensure that the results were not subject to multicollinearity problems, variance inflation factors (VIFs) were checked carefully. None of the VIF values exceeded the threshold of 10 (Myers & Myers, 1990), ranging from 1.03 to 1.32 with a mean VIF of 1.12. Hence, we argue that multicollinearity does not pose a serious threat to this study. Closer inspection further revealed that (1) WFC was positively correlated with entrepreneurial regret (r = 0.160, p < 0.01), while (2) entrepreneurial regret was positively correlated with exit intention (r = 0.342; p < 0.01) and (3) negatively correlated with work satisfaction (r = -0.423, p < 0.01). Therefore, preliminary results support our hypotheses.

Hypotheses testing

We examined the mediation and moderated mediation hypotheses using the PROCESS SPSS macro (Hayes, 2013; Preacher et al., 2007). This bootstrapping procedure represents a reliable statistical tool that helps researchers to simultaneously examine moderated indirect effects based on bootstrapping procedures (Hayes & Preacher, 2014; Preacher et al., 2007). Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b) propose that entrepreneurial regret is a mediating mechanism through which WFC predicts exit intention and work satisfaction, respectively. Table 3 highlights that the indirect effect of WFC on exit intention through entrepreneurial regret is positive and statistically significant (indirect effect = 0.05, SE = 0.02, 95% CI from 0.01 to 0.09), while the indirect effect of WFC on work satisfaction through entrepreneurial regret is negative and significant (indirect effect = -0.06, standard error [SE] = 0.02, 95% confidence interval [CI] from -0.11 to -0.02). Simply put, when female entrepreneurs encounter WFC, they are more likely to engage in entrepreneurial regret and subsequently experience negative work outcomes including higher levels of exit intention and lower levels of work satisfaction. These results align with our model prediction, and therefore, fully support Hypotheses 1(a) and 1(b).

We next turn to Hypotheses 2(a) and 2(b), which propose that the indirect effect of WFC in the two work outcomes via entrepreneurial regret would be determined by the level of social support that female entrepreneurs can receive from their family members. Specifically, we expected family support to serve as a first-stage boundary condition that would assist entrepreneurs in coping with their WFC experience. As shown in Table 3, the cross-product term (WFC × Family Support) in predicting entrepreneurial regret was significant (coefficient = -0.03, 95% CI from -0.05 to -0.005). Figure 2 clearly indicates that the positive association between WFC and entrepreneurial regret is stronger when the level of family support is low, while it becomes weaker when the level of support is high. Thus, we confirm that female entrepreneurs engage in entrepreneurial regret because they suffer from WFC and lack of family support. Conversely, their engagement in entrepreneurial regret may weaken when the level of family support is high.

Similarly, the conditional indirect effect of WFC on exit intention via entrepreneurial regret became stronger when the family support was low (indirect effect = 0.08, SE = 0.03, 95% CI from 0.03 to 0.14); however they were not significant with high levels of family support (indirect effect = 0.01, SE = 0.03, 95% CI from -0.04 to 0.06). The index of moderated mediation (Hayes, 2015) was -0.03 (95% CI from -0.05 to -0.002). These results are summarized in Table 4. Our results show that female entrepreneurs regret their decision to pursue an entrepreneurial career because they experienced WFC. Furthermore, they subsequently develop a stronger intention to exit from their current entrepreneurship, specifically when the level of family support is low, which supports Hypothesis 2(a).

Finally, the conditional indirect effect of WFC on work satisfaction via entrepreneurial regret became stronger when family support levels were low (indirect effect = -0.10, SE = 0.03, 95% CI from -0.17 to -0.04), but this effect became weaker (non-significant) when family support levels were high (indirect effect = -0.01, SE = 0.03, 95% CI from -0.08 to 0.05). The significant index of moderated mediation (index = 0.03, 95% CI from 0.003 to 0.07) reveals that the moderating role of family support is linearly associated with the mediated model and not just a specific path in the model (e.g., the a or b path of the indirect effect; Hayes, 2013). These results are presented in Table 4. In summary, the results suggest that female entrepreneurs are more likely to experience regret about the decision to start and engage in entrepreneurial activities, and subsequently experience less satisfaction with their work as a result of their WFC experiences. This is particularly likely when they have low levels of family support. These findings support Hypothesis 2(b).

Discussion and conclusion

Theoretical implications

Our study has Important theoretical implications. First, we cast a spotlight on entrepreneurial regret by positing it as a cognitive mechanism that may explain how female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences influence their satisfaction with and commitment to their entrepreneurial journey. While the study of the mediating mechanisms in the relationship between WFC and work outcomes is not new, many studies adopted a stress perspective to explain how people generally react to WFC as a stressful situation (Rabenu et al., 2017; Stoeva et al., 2002). For instance, the mediating roles of emotional exhaustion (Karatepe, 2013) and stress interventions (Carroll et al., 2013) have been highlighted. Drawing upon SCT (Bandura, 1989), this study provides an alternative perspective and posits that people do not necessarily react passively to their surrounding circumstances. Rather, they may utilize their forethought capability to carefully weigh the advantages and disadvantages of a specific situation, to determine how they should proceed, in this context, with entrepreneurial endeavors. Correspondingly, our results suggest that when female entrepreneurs experience WFC, they may engage in entrepreneurial regret contemplating what the situation might have been like if they had acted in a different manner (Baron, 2000). Indeed, entrepreneurial regret reflects a forethought of negative outcomes, further leading to negative attitudes, including increased exit intention and lower work satisfaction.

By considering family support as a critical boundary condition of the effect of WFC, this study provides new insights into the complex mechanism linking WFC with entrepreneurial outcomes via regretful thinking. Specifically, we found that lower family support levels cause female entrepreneurs to foresee negative outcomes associated with WFC. This can be reflected in higher levels of entrepreneurial regret, which, in turn, increase their intention to exit their existing business ventures and reduce their work commitment. Previous studies have revealed that the relationship between WFC and outcomes is not straightforward, and that empirical inconsistencies exist (Welsh & Kaciak, 2018). Such variations can be explained by boundary conditions such as family support. Accordingly, the results of this study suggest that the quality and nature of the relationship between WFC and outcomes can vary depending on contingent factors such as family support.

Finally, our research contributes to the literature on female entrepreneurs in two important ways. First, we treated women as heterogeneous rather than as a homogenous group. We examined significant differences among female entrepreneurs in terms of age, education, and prior experience in entrepreneurship. In doing so, we departed from past studies that merely compared male and female entrepreneurs (e.g., Hsu et al., 2016; Powell & Eddleston, 2013). We thereby also responded to recent calls for further research (e.g., Brush et al., 2019; Fielden & Hunt, 2011) to account for variations among female entrepreneurs in studies of entrepreneurship. Second, we conducted this study in a Japanese entrepreneurship context – a society in which patriarchal norms are still observed. Many women in Japan experience negative gender-role stereotypes that inhibit them from accessing critical resources and career growth opportunities (Futagami & Helms, 2009). Hence, in this research context, female entrepreneurs inevitably experience heightened levels of WFC.

Practical implications

The findings of this study also have some important practical implications. We found that WFC during the COVID-19 pandemic gave rise to a negative sentiment of “I should not have been committed to entrepreneurial activity,” which escalates female entrepreneurs’ exit intention and reduces their work satisfaction. This may be concerning, especially for the Japanese government, which aims to integrate women’s entrepreneurial initiatives into the national economy. Our findings indicate that it is paramount for both central and local governments to consider recreating an entrepreneurial ecosystem that is aimed at promoting work-family balance among female entrepreneurs. Specifically, public policymakers and entrepreneurship support agencies must understand the importance of accounting for the gendered nature of work and family responsibilities. We advise that these agencies proactively provide female entrepreneurs, as well as their partners, spouses, and other family members with training sessions that primarily address the issue of managing and nurturing their work-life balance. Such training sessions could serve as an educational opportunity for family members to develop a sense of group cohesion and make them aware of the importance of allowing female entrepreneurs to access and leverage family resources, especially in the face of an economic crisis (Wijewardena et al., 2020). Our findings also suggest that public policymakers and entrepreneurship support agencies should make greater efforts to offer financial support to married female entrepreneurs to facilitate access to childcare and domestic services, thereby alleviating the pressure of work-family demands (Shelton, 2006). Another significant implication is that female entrepreneurs need increased access to non-financial support, such as mentoring and coaching services, by experienced female entrepreneurs who are knowledgeable about coping with WFCs. From a public policy perspective, mentorship programs could offer invaluable opportunities for mentees to participate in tailored training programs aimed at guiding female entrepreneurs to realize their career advancement and foster a peaceful family life at the same time (De Clercq et al., 2021a, b). They can also connect female entrepreneurs with successful female role models (Austin & Nauta, 2016) and small business and entrepreneurial advisory centers (Shelton, 2006). Lastly, they can deliver counseling services on work-family management strategies and offer emotional and instrumental support for current and prospective female entrepreneurs.

Limitations and suggestions for future research

Notwithstanding the crucial contributions, this study has limitations that can be considered possible opportunities for future research. First, we collected our data using a cross-sectional design, which precludes causal inferences. However, reverse causality is unlikely here as the observed moderation results would not make sense in the reversed causal direction; this supports our proposed theoretical model. Nevertheless, to confirm a causal relationship, future studies should use more robust approaches, such as employing a longitudinal design and utilizing archival data to determine the actual number of exits from business ventures.

Second, our proposed research model was empirically tested using a sample of married female entrepreneurs in Japan. Therefore, this study’s findings may not be applicable to other socio-cultural contexts. For instance, in Nordic countries, it is common for men to do more housework than their female counterparts (Puur et al., 2008). Additional research in different cultural settings is required to determine the generalizability of our findings. Cross-cultural studies are particularly useful in identifying variations among female entrepreneurs. However, our results are noteworthy in that they elucidated female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences in countries with patriarchal gender norms.

There are various ways in which future studies can build upon this study to contribute further to entrepreneurship and WFC literature. For instance, while our study empirically determined exit intention as a dependent outcome of female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences, a behavioral manifestation of exit intention can be further determined by considering the actual number of exits and exit strategies individuals adopted (e.g., Bird & Wennberg, 2016; Wennberg & DeTienne, 2014). Furthermore, the interplay between female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences and associated cognitive mechanisms, such as entrepreneurial regret, can be further explicated using different contingent factors. In this study, we primarily focused on family support; we suggest that focusing more on the entrepreneurs themselves may also provide some interesting insights related to individuals’ psychological resources (e.g., self-efficacy and resilience: Baum & Locke, 2004; Baum et al., 2001) and role identity (Hsu et al., 2016), for example.

Conclusion

Considering SCT (Bandura, 1986) as an analytical lens, this study sought to explicate the cognitive mechanisms associated with female entrepreneurs’ WFC experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. We specifically focused on their engagement in entrepreneurial regret. These regrets have further implications for their decision to either continue or discontinue their entrepreneurial journey, as reflected in their exit intention, and their attitudes toward their current entrepreneurial path, as reflected in their work satisfaction. Importantly, our results signal that family support serves as a vital condition that may attenuate the negative consequences that may result from WFC.

Notes

To deal with this issue, we conducted the reliability test using the Spearman-Brown formula (Eisinga et al., 2013) and found that doubling the test resulted in the increased composite reliability. This methodological remedy is widely adopted by extant research in the area of the entrepreneurship (Hmieleski et al., 2015). Therefore, we conclude that this two-item measure would not negatively affect the empirical results of this study.

References

Afshan, G., Shahid, S., & Tunio, M. N. (2021). Learning experiences of women entrepreneurs amidst COVID-19. International Journal of Gender & Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 162–186.

Ahl, H. (2006). Why research on women entrepreneurs needs new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 30(5), 595–621.

Aldrich, H. E., & Cliff, J. E. (2003). The pervasive effects of family on entrepreneurship: Toward a family embeddedness perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(5), 573–596.

Araújo Nocedo, A. M. (2012). The “good wife and wise mother” pattern: Gender differences in today’s Japanese society. Crítica Contemporánea. Revista De Teoría Política, 2, 156–169.

Austin, M. J., & Nauta, M. M. (2016). Entrepreneurial role-model exposure, self-efficacy, and women’s entrepreneurial intentions. Journal of Career Development, 43(3), 260–272.

Ayatakshi-Endow, S., & Steele, J. (2021). Striving for balance: Women entrepreneurs in Brazil, their multiple gendered roles and Covid-19. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 13(2), 121–141.

Bandura, A. (1986). Social foundations of thought and action: A social cognitive theory. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

Bandura, A., & Locke, E. A. (2003). Negative self-efficacy and goal effects revisited. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(1), 87–99.

Baron, R. A. (2000). Counterfactual thinking and venture formation: The potential effects of thinking about “what might have been.” Journal of Business Venturing, 15(1), 79–91.

Baum, J. R., & Locke, E. A. (2004). The relationship of entrepreneurial traits, skill, and motivation to subsequent venture growth. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(4), 587–598.

Baum, J. R., Locke, E. A., & Smith, K. G. (2001). A multidimensional model of venture growth. Academy of Management Journal, 44(2), 292–303.

Bird, M., & Wennberg, K. (2016). Why family matters: The impact of family resources on immigrant entrepreneurs’ exit from entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 687–704.

Bobrowska, S., & Conrad, H. (2017). Discourses of female entrepreneurship in the Japanese business press–25 years and little progress. Japanese Studies, 37(1), 1–22.

Brislin, R. W. (1970). Back-translation for cross-cultural research. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 1(3), 185–216.

Brush, C., Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., & Welter, F. (2019). A gendered look at entrepreneurship ecosystems. Small Business Economics, 53, 393–408.

Cammann, C., Fichman, M., Jenkins, D., & Klesh, J. R. (1983). Assessing the attitudes and perceptions of organizational members. In S. E. Seashore, E. E. Lawler, P. H. Minis, & C. Cammann (Eds.), Assessing organizational change: A guide to methods, measures, and practices (pp. 71–138). Wiley.

Carr, J. C., & Hmieleski, K. M. (2015). Differences in the outcomes of work and family conflict between family–and nonfamily businesses: An examination of business founders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(6), 1413–1432.

Carroll, S. J., Hill, E. J., Yorgason, J. B., Larson, J. H., & Sandberg, J. G. (2013). Couple communication as a mediator between work–family conflict and marital satisfaction. Contemporary Family Therapy, 35(3), 530–545.

Cerrato, J., & Cifre, E. (2018). Gender inequality in household chores and work-family conflict. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1330–1341.

Chang, E. P., Memili, E., Chrisman, J. J., Kellermanns, F. W., & Chua, J. H. (2009). Family social capital, venture preparedness, and start-up decisions: A study of Hispanic entrepreneurs in New England. Family Business Review, 22(3), 279–292.

Collins-Dodd, C., Gordon, I. M., & Smart, C. (2004). Further evidence on the role of gender in financial performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 42(4), 395–417.

Cortina, J. M. (1993). What is coefficient alpha? An examination of theory and applications. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78(1), 98–104.

De Clercq, D., Brieger, S. A., & Welzel, C. (2021a). Leveraging the macro-level environment to balance work and life: An analysis of female entrepreneurs’ job satisfaction. Small Business Economics, 56(4), 1361–1384.

De Clercq, D., Kaciak, E., & Thongpapanl, N. (2021b). Work-to-family conflict and firm performance of women entrepreneurs: Roles of work-related emotional exhaustion and competitive hostility. International Small Business Journal, 1–21.

Eagly, A. H. (1987). Reporting sex differences. American Psychologist, 42(7), 756–757.

Eddleston, K. A., & Powell, G. N. (2012). Nurturing entrepreneurs’ work-family balance: A gendered perspective. Entrepreneurship Theory & Practice, 36(3), 513–541.

Edelman, L. F., Manolova, T., Shirokova, G., & Tsukanova, T. (2016). The impact of family support on young entrepreneurs’ start-up activities. Journal of Business Venturing, 31, 428–448.

Eisinga, R., Grotenhuis, M. T., & Pelzer, B. (2013). The reliability of a two-item scale: Pearson, Cronbach, or Spearman-Brown? International Journal of Public Health, 58(4), 637–642.

Fielden, S. L., & Hunt, C. M. (2011). Online coaching: An alternative source of social support for female entrepreneurs during venture creation. International Small Business Journal, 29(4), 345–359.

Fried, Y., Tiegs, R. B., Naughton, T. J., & Ashforth, B. E. (1996). Managers’ reactions to a corporate acquisition: A test of an integrative model. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17(5), 401–427.

Futagami, S., & Helms, M. M. (2009). Emerging female entrepreneurship in Japan: A case study of Digimom workers. Thunderbird International Business Review, 51(1), 71–85.

Gherardi, S. (2015). Authoring the female entrepreneur while talking the discourse of work–family life balance. International Small Business Journal, 33(6), 649–666.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2021). Women’s Entrepreneurship 2020/21: Thriving Through Crisis. Babson College, Babson Park, MA.

Global Entrepreneurship Monitor. (2022). Global Entrepreneurship Monitor 2021/2022 Global Report: Opportunity Amid Disruption. GEM.

Graeber, D., Kritikos, A. S., & Seebauer, J. (2021). COVID-19: A crisis of the female self-employed. Journal of Population Economics, 34(4), 1141–1187.

Grandy, G., Cukier, W., & Gagnon, S. (2020). (In) visibility in the margins: COVID-19, women entrepreneurs and the need for inclusive recovery. Gender in Management: An International Journal, 35(7/8), 667–675.

Greenhaus, J., & Beutell, N. (1985). Sources and conflict between work and family roles. Academy of Management Review, 10(1), 76–88.

Greenhaus, J. H., & Parasuraman, S. (1999). Research on work, family, and gender: Current status and future directions. In G. N. Powell (Ed.), Handbook of gender and work (pp. 391–412). Sage Publications.

Gudmunson, C. G., Danes, S. M., Werbel, J. D., & Loy, J. T. C. (2009). Spousal support and work family balance in launching a family business. Journal of Family Issues, 30(8), 1098–1121.

Harman, H. H. (1967). Modern factor analysis. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2013). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Hayes, A. F. (2015). An index and test of linear moderated mediation. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 50(1), 1–22.

Hayes, A. F., & Preacher, K. J. (2014). Statistical mediation analysis with a multicategorical independent variable”. British Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Psychology, 67(3), 451–470.

Hmieleski, K. M., Carr, J. C., & Baron, R. A. (2015). Integrating discovery and creation perspectives of entrepreneurial action: The relative roles of founding CEO human capital, social capital, and psychological capital in contexts of risk versus uncertainty. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 9(4), 289–312.

Hsu, D. K., Shinnar, R. S., & Anderson, S. E. (2019). ‘I wish I had a regular job’: An exploratory study of entrepreneurial regret. Journal of Business Research, 96, 217–227.

Hsu, D. K., Wiklund, J., Anderson, S. E., & Coffey, B. S. (2016). Entrepreneurial exit intentions and the business-family interface. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 613–627.

Hughes, K. D., Jennings, J. E., Brush, C., Carter, S., & Welter, F. (2012). Extending women’s entrepreneurship research in new directions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(3), 429–442.

Jaim, J. (2021). Exist or exit? Women business-owners in Bangladesh during COVID-19. Gender, Work & Organization, 28(S1), 209–226.

Jennings, J., & Brush, C. G. (2013). Research on women entrepreneurs: Challenges to (and from) the broader entrepreneurship literature? Academy of Management Annals, 7(1), 661–713.

Jennings, J., & McDougald, M. (2007). Work-family interface experiences and coping strategies: Implications for entrepreneurship research and practice. Academy of Management Review, 32(3), 747–760.

Karatepe, O. M. (2013). The effects of work overload and work-family conflict on job embeddedness and job performance: The mediation of emotional exhaustion. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 25(4), 614–634.

Khanin, D., Turel, O., Mahto, R. V., & Liguori, E. W. (2021). Betting on the wrong horse: The antecedents and outcomes of entrepreneur’s opportunity regret. Journal of Business Research, 135, 40–48.

King, L. A., Mattimore, L. K., King, D. W., & Adams, G. A. (1995). Family support inventory for workers: A new measure of perceived social support from family members. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 16(3), 235–258.

Kline, P. (1999). Handbook of Psychological Testing. Routledge.

Leung, A., Zietsma, C., & Peredo, A. M. (2014). Emergent identity work and institutional change: The ‘quiet’ revolution of Japanese middle-class housewives. Organization Studies, 35(3), 423–450.

Liñán, F., Jaén, I., & Martín, D. (2020). Does entrepreneurship fit her? Women entrepreneurs, gender-role orientation, and entrepreneurial culture. Small Business Economics, 1–21.

Lindell, M. K., & Whitney, D. J. (2001). Accounting for common method variance in cross sectional research designs. Journal of Applied Psychology, 86(1), 114–121.

Liu, Y., Schøtt, T., & Zhang, C. (2019). Women’s experiences of legitimacy, satisfaction and commitment as entrepreneurs: Embedded in gender hierarchy and networks in private and business spheres. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(3–4), 293–307.

Manolova, T. S., Brush, C. G., Edelman, L. F., & Elam, A. (2020). Pivoting to stay the course: How women entrepreneurs take advantage of opportunities created by the COVID-19 pandemic. International Small Business Journal, 38(6), 481–491.

Manolova, T. S., Carter, N. M., Manev, I. M., & Gyoshev, B. S. (2007). The differential effect of men and women entrepreneurs’ human capital and networking on growth expectancies in Bulgaria. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 31(3), 407–426.

Mari, M., Poggesi, S., & De Vita, L. (2016). Family embeddedness and business performance: Evidence from women-owned firms. Management Decision, 54(5), 476–500.

Markman, G. D., Baron, R. A., & Balkin, D. B. (2005). Are perseverance and self-efficacy costless? Assessing entrepreneurs’ regretful thinking. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 26(1), 1–19.

Martins, L. L., Eddleston, K. A., & Veiga, J. F. (2002). Moderators of the relationship between work-family conflict and career satisfaction. Academy of Management Journal, 45(2), 399–409.

Myers, R. H., & Myers, R. H. (1990). Classical and modern regression with applications (Vol. 2, p. 488). Belmont, CA: Duxbury press.

Netemeyer, R. G., Boles, J. S., & McMurrian, R. (1996). Development and validation of work–family conflict and family–work conflict scales. Journal of Applied Psychology, 81(4), 400–410.

Nunnally, J. (1978). Psychometric theory (2nd ed.). McGraw-Hill.

OECD. (2021). Caregiving in crisis: Gender inequality in paid and unpaid work during COVID-19. Retrieved April 17, 2021, from https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/caregiving-in-crisis-gender-inequality-in-paid-and-unpaid-work-during-covid-19-3555d164

Podsakoff, P. M., MacKenzie, S. B., Lee, J. Y., & Podsakoff, N. P. (2003). Common method biases in behavioral research: A critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. Journal of Applied Psychology, 88(5), 879–903.

Podsakoff, P. M., & Organ, D. W. (1986). Self-reports in organizational research: Problems and prospects. Journal of Management, 12(4), 531–544.

Poggesi, S., Mari, M., & De Vita, L. (2019). Women entrepreneurs and work-family conflict: An analysis of the antecedents. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 15(2), 431–454.

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2013). Linking family-to-business enrichment and support to entrepreneurial success: Do female and male entrepreneurs experience different outcomes? Journal of Business Venturing, 28(2), 261–280.

Powell, G. N., & Eddleston, K. A. (2017). Family involvement in the firm, family-to-business support, and entrepreneurial outcomes: An exploration. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(4), 614–631.

Prasad, V. K., Naidu, G. M., Murthy, B. K., Winkel, D. E., & Ehrhardt, K. (2013). Women entrepreneurs and business venture growth: An examination of the influence of human and social capital resources in an Indian context. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 26(4), 341–364.

Preacher, K. J., Rucker, D. D., & Hayes, A. F. (2007). Addressing moderated mediation hypotheses: Theory, methods, and prescriptions. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 42(1), 185–227.

Puur, A., Oláh, L. S., Tazi-Preve, M. I., & Dorbritz, J. (2008). Men’s childbearing desires and views of the male role in Europe at the dawn of the 21st century. Demographic Research, 19, 1883–1912.

Rabenu, E., Tziner, A., & Sharoni, G. (2017). The relationship between work-family conflict, stress, and work attitudes. International Journal of Manpower, 38(8), 1143–1156.

Rigoni, G., Herrmann, K., Lyons, A. C., Wilkinson, B., Kass-Hanna, J., Bennett, D., Stracquadaini, J., & Thomas, M. (2021). Policy brief: The economic empowerment of women entrepreneurs in a post-COVID world. Task Force 5 2030 Agenda and Development Cooperation. pp. 1–17.

Roese, N. J. (1997). Counterfactual thinking. Psychological Bulletin, 121(1), 133–148.

Saridakis, G., Lai, Y., Mohammed, A. M., & Hansen, J. M. (2018). Industry characteristics, stages of E-commerce communications, and entrepreneurs and SMEs revenue growth. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 128, 56–66.

Schjoedt, L. (2021). Exploring differences between novice and repeat entrepreneurs: Does stress mediate the effects of work-and-family conflict on entrepreneurs’ satisfaction? Small Business Economics, 56(4), 1251–1272.

Shelton, L. M. (2006). Female entrepreneurs, work–family conflict, and venture performance: New insights into the work–family interface. Journal of Small Business Management, 44, 285–297.

Shockley, K. M., & Allen, T. D. (2018). It’s not what I expected: The association between dual-earner couples’ met expectations for the division of paid and family labor and well-being. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 104, 240–260.

Singh, R., Zhang, Y., Wan, M., & Fouad, N. A. (2018). Why do women engineers leave the engineering profession? The roles of work–family conflict, occupational commitment, and perceived organizational support. Human Resource Management, 57(4), 901–914.

Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Social cognitive theory and self-efficacy: Goin beyond traditional motivational and behavioral approaches. Organizational Dynamics, 26(4), 62–74.

Stephan, U., Zbierowski, P., & Hanard, P. J. (2020). Entrepreneurship and Covid-19: Challenges and opportunities. KBS Covid-19 Research Impact Papers, 2, 1–30.

Stoeva, A. Z., Chiu, R. K., & Greenhaus, J. H. (2002). Negative affectivity, role stress, and work–family conflict. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 60(1), 1–16.

Tabachnick, B. G., Fidell, L. S., & Ullman, J. B. (2007). Using multivariate statistics (Vol. 5, pp. 481–498). Boston, MA: Pearson.

Thébaud, S. (2015). Business as plan B: Institutional foundations of gender in equality in entrepreneurship across 24 industrialized countries. Administrative Science Quarterly, 60(4), 671–711.

Vershinina, N., Rodgers, P., Tarba, S., Khan, Z., & Stokes, P. (2020). Gaining legitimacy through proactive stakeholder management: The experiences of high-tech women entrepreneurs in Russia. Journal of Business Research, 119, 111–121.

Welsh, D. H., & Kaciak, E. (2018). Women’s entrepreneurship: A model of business-family interface and performance. International Entrepreneurship and Management Journal, 14(3), 627–637.

Welsh, D. H., Kaciak, E., Mehtap, S., Pellegrini, M. M., Caputo, A., & Ahmed, S. (2021). The door swings in and out: The impact of family support and country stability on success of women entrepreneurs in the Arab world. International Small Business Journal, 39(7), 619–642.

Welsh, D. H., Memili, E., Kaciak, E., & Ochi, M. (2014). Japanese women entrepreneurs: Implications for family firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 52(2), 286–305.

Welsh, D. H. B., Kaciak, E., & Thongpapanl, N. (2016). Influence of stages of economic development on women entrepreneurs’ startups. Journal of Business Research, 69(11), 4933–4940.

Wennberg, K., & DeTienne, D. R. (2014). What do we really mean when we talk about ‘exit’? A critical review of research on entrepreneurial exit. International Small Business Journal, 32(1), 4–16.

Wijewardena, N., Samaratunge, R., Kumara, A. S., Newman, A., & Abeysekera, L. (2020). It takes a family to lighten the load! The impact of family-to-business support on the stress and creativity of women micro-entrepreneurs in Sri Lanka. Personnel Review, 49(9), 1965–1986.

Xu, F., Kellermanns, F. W., Jin, L., & Xi, J. (2020). Family support as social exchange in entrepreneurship: Its moderating impact on entrepreneurial stressors-well-being relationships. Journal of Business Research, 120, 59–73.

Zeelenberg, M., van Dijk, W. W., van der Pligt, J., Manstead, A. S. R., van Empelen, P., & Reinderman, D. (1998). Emotional reactions to the outcomes of decisions: The role of counterfactual thought in the experience of regret and disappointment. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 75(2), 117–141.

Acknowledgements

This research project was financially supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI, 19K01810) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS).

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kawai, N., Sibunruang, H. & Kazumi, T. Work-family conflict, entrepreneurial regret, and entrepreneurial outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Int Entrep Manag J 19, 837–861 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00846-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11365-023-00846-5