Abstract

Background

FitBack is an international network established to support the creation of physical fitness monitoring and surveillance systems for children and adolescents across Europe.

Aims

As a part of the greater scope of the FitBack European project, the FitBack web portal was designed and tailored for various target groups, such as teachers, health professionals, policy makers, parents, and youths, with the aim to promote their physical and health literacy.

Methods

The FitBack web portal is a free and multilingual online resource, and two of its webpages were evaluated: “Make interactive report” was evaluated by 78 secondary school students and 27 physical education teachers, and “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system” by 14 physical activity promotion policy makers. Validated scales and open-ended questions were used to collect both quantitative and qualitative responses.

Results

‘Good’-to-‘excellent’ scores emerged for user experience (5.43–6.36 out of 7) and webpage usability (3.70–4.27 out of 5). Qualitative feedback highlighted positive comments and cues on how to improve website features.

Conclusions

Results indicate that the current FitBack web portal is a clear and user-friendly mobile health tool, which includes relevant information on how to use and implement youth physical fitness monitoring and surveillance systems.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

A growing body of knowledge links children and adolescents’ physical activity (PA) and physical fitness (PF) to positive health outcomes [1, 2], cognitive function [3], and academic performance [4, 5]. PA practice is directly related to individual’s PF [6], which, in turn, is also dependent from genetic factors, and nutrition [7, 8]. A number of cross-sectional studies have associated PA and PF to health-related outcomes, such as body composition and sleep time [2, 9, 10]. Similarly, a recent systematic review of the scientific literature found correlational evidence between PA, PF, and cognitive functions, such as working memory and attention, in children in the age between 5 and 13 years [3]. A positive association between PF and academic achievement is also supported by longitudinal studies [5]. Scientific studies on this topic often observe PF as a result of PA levels [11, 12], but it is also true, for example, that unfit people can experience fitness-shame and be less physically active [13]. Poor PF can, therefore, be seen as a consequence of poor PA and vice versa. The implementation of specific fitness monitoring systems, extended at regional, national, and international levels, can be beneficial for youths in terms of health, educational, and sport participation outcomes [14].

Fitness monitoring and surveillance are amongst the top health priorities recognised by health expert panels to better promote physically active lifestyles and prevent non-communicable diseases [15,16,17]. Mobile health (mHealth) technologies can facilitate testing, monitoring, and the provision of appropriate feedback to users [18,19,20]. Emerging technologies, such as multimedia interfaces and mobile applications, have already demonstrated their role in empowering people to change their behaviours and are widely used for promoting health, life-long engagement in PA, and the adoption of healthy lifestyles [19, 21]. With particular regards to fitness monitoring, e-technologies can increase the usability and availability of fitness data, enhancing both monitoring and/or surveillance and, as a consequence, impacting population-based healthcare programmes.

Evaluating health promotion websites

Over the last few decades, Internet has become a prominent reference source regarding information on health, PA, and PF; however, this open information can be made vulnerable by external purposes (e.g., commercial ones) affecting content quality, accuracy, convey misleading conclusions, and thus raise concerns for final users [22]. In fact, lay users may not be able to recognise inaccurate or even misleading information, especially as it relates to PA and PF [23]. This concern is even more relevant for websites and services designed for children and adolescents. In fact, although younger generations are generally more confident with emerging technology, and they often have the possibility to independently seek health-related information on the Internet [24], they may not yet have adequate physical and health literacy [25, 26] to discern high quality or false/misleading online contents. For these reasons, Park and Kwon [27] have suggested that health-related websites designed for children and adolescents should be adequately evaluated to offer resources and content tailored for these age groups.

Best practices in website evaluation [28, 29] suggest combining quantitative and qualitative methods, adopting validated quantitative instruments, and involving real end-users for assessment. Quantitative methods allow for comparison tests [30], whereas qualitative methods are generally more useful to identifying websites issues and providing cues for further development. Webpage usability (i.e., content readability, design, and effectiveness) and user experience (i.e., the overall quality of the human–computer interaction) are two criteria commonly used during websites’ evaluation, and validated measures for these constructs are available in the literature [31, 32]. Finally, a citizen science-based approach [33], which involves the real public in the evaluation and co-design of the product, appear to be a good strategy to take into account users’ characteristics, knowledge, and views.

An overview of the FitBack web portal

FitBack (www.fitbackeurope.eu) is a project co-funded by the Erasmus + Sport programme of the European Union, aiming at developing a web portal to support monitoring youth PF across Europe. The portal acts as a gateway to knowledge, data, and resources which support the development of PF monitoring and surveillance systems from a local, regional, or national perspective.

First, the webpage named “Make interactive report” allows children and adolescents or their teachers or parents to insert information (date of birth, gender/sex, height, and weight) and fitness data to receive comprehensive group or individual health reports (see Fig. 1). Specifically, it is possible to input test results for three fitness tests (20 m shuttle run, standing long jump, and handgrip strength), considered amongst the most indicative of actual health outcomes [34,35,36]. Users can receive interactive feedback on their own performance, create PDF reports, export scores, and receive their feedback in an Excel document, or they can opt to send a link with their report to somebody else (e.g., teachers or medical professionals). It is also possible for physical education (PE) teachers and coaches to insert group fitness data relating to their classroom pupils or teams onto the portal. Importantly, any data entered to the FitBack portal are not stored within the platform itself; users do have an option to store the data on a personal saving location of their choosing.

A second webpage on the FitBack portal is named the “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system”, which provides public health and educational institutions with suggestions on how to involve stakeholders and establish PF monitoring and surveillance systems at local, regional, or national levels. These suggestions included ten key points which are pursued in consequential order: (1) definition of aims, (2) stakeholders’ involvement, (3) use of a scientific background, (4) involvement of governing bodies, (5) fundraising, (6) data management planning, (7) provision of feedback to users and stakeholders, (8) pilot testing, (9) implementation, and (10) communication to the public.

The importance of establishing systematic PF monitoring and surveillance

Systematic PF monitoring and surveillance in children and adolescents can help track motor and somatic development, and contribute to better planning, implementation, and assessment of PA promotion interventions at school and in other educational settings [37]. By receiving regular evidence-based feedback, fitness surveillance systems contribute to the physical literacy of children and adolescents, reinforcing the habit-forming behaviour of pursuing regular, daily physical activity [38, 39]. For example, Slovenia has a well-established national child fitness surveillance system called “SLOfit”, which has been in action for over 3 decades [39]. Based on annual monitoring, surveillance, and observed secular PF trends, SLOfit experts have been successful in urging policy makers to enact PA and PF interventions at the population level after observing the sudden negative PF trends in childhood fitness levels from the period of 2000–2010, and more recently due to the COVID-19 pandemic [40, 41]. Evidence-based near real-time fitness data are urgently needed worldwide to counteract the negative trends in youths’ PA.

Aim and objectives

The aim and objectives of the present study were to evaluate the FitBack web portal and to inform its development. In detail: (a) the webpages “Make interactive report” and “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system” were expected to receive positive quantitative assessments from students, PE teachers, and policy makers in terms of user experience and web usability; (b) useful cues for the improvement of the web portal were expected to emerge from the end-users’ qualitative responses; and (c) overall positive qualitative feedback was also expected regarding the two webpages.

Methods

Procedure

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and received approval by the institutional Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Sport, University of Ljubljana (No. 033-11/2021-2).

This pilot testing study was developed in two phases. The first phase (Phase 1) included a discussion amongst FitBack members on the web portal content and design, and a revision/refinement of the existing measures and methods used for website evaluation. Literature on human–computer interaction was reviewed to identify appropriate website evaluation measures [31, 32, 42] and develop a questionnaire package to evaluate the FitBack web portal. Furthermore, open-ended questions were added to allow for participants’ opinions and preferences [28]. The questionnaire was examined by each of the manuscript authors individually, revised according to comments, and uploaded to an online survey platform (surveymonkey.com).

In the second piloting phase (Phase 2), opportunity sampling and snowball sampling methods were adopted to achieve members of the population of interest. PE teachers and policy makers were selected amongst authors’ networks and contacted via direct approach (opportunity sampling). PE teachers were then asked to suggest interested students to complete the survey as well (snowball sampling). Since the FitBack web portal was initially available only in English, participants were selected only if they had a good command of this language. This procedure allowed to involve real end-users in the website evaluation study.

If interested to partake in the study, participants were invited to complete the survey via smartphones, tablets, laptops, or personal computers (PCs), which were all considered suitable devices from which end-users could visit and access the FitBack portal. Students and PE teachers were sent a link to access the webpage “Make interactive report”, whereas policy makers invited to evaluate the webpage “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system”. When accessing the online survey, participants could select their native language for knowing the research aims and description, providing their informed consent and agreement to participate in the study, and reading the open-ended questions. Web usability and user experience evaluation scales were presented in English language; this choice was made not to affect the validity of the scale and based on the fact that all participants were confident with this language. Participants were free to interrupt or quit their survey at any point, without explaining the reason for doing so. Following quantitative assessment, participants were asked to consult again the web page and to answer open-ended questions to provide their qualitative feedback.

Participants

Three groups of users were recruited from six European countries: Croatia, Estonia, Italy, Serbia, Slovenia, and Spain (N = 119 total). In detail: 78 secondary school students (31 girls; age range 12–19 years; 9% Croatian, 5% Estonian, 30% Italian, 6% Serbian, 28% Slovenian, 22% Spanish), 27 PE teachers (12 women; M age = 37.8 years, SD = 6.4; 15% Croatian, 15% Estonian, 26% Italian, 7% Serbian, 7% Slovenian, 30% Spanish), and 14 policy makers within the area of PA promotion (6 women; M age = 46.8 years, SD = 9.4; 14% Croatian, 14% Estonian, 21% Italian, 14% Serbian, 14% Slovenian, 21% Spanish). These groups well represent the European population of secondary school students in terms of age and gender, and student–teacher ratio [43, 44]. Additionally, the balanced gender ratio of PE teachers and policy makers can be considered representative of the general population.

Measures

User experience

For the assessment of user experience, a short version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S [32]) was adopted for all participants (in English). Items were introduced by the stem “Navigating the webpage was …” and possible answers were given on a 7-point Likert scale (range 1–7), with two opposite words at the two ends, for example “Complicated”—“Easy”. The scale demonstrated satisfactory to excellent internal consistency reliability for the three considered samples, with Cronbach alpha values ranging from 0.73 to 0.91 (see Table 1 for full details). For comparing user experience assessments with those of other websites, Schrepp and colleagues (2017 [30]) also developed a benchmark for the UEQ-S, which is yearly updated (www.ueq-online.org). According to their benchmark, websites can be classified as either ‘bad’ (M range = 1.00–4.59), ‘below average’ (M range = 4.60–4.98), ‘above average’ (4.99–5.31), ‘good’ (M range = 5.32–5.58), or ‘excellent’ (M range = 5.59–7.00).

Web usability

The usability of the FitBack web portal was assessed using two different scales, chosen according to the age of participants. For students, the scale consisted of a web usability scale for adolescents, originally developed by Bailey and Seals (2017 [31]). For teachers and policy makers, the WebUse scale [42] was adopted. In both scales, items were introduced by the stem “Please, indicate how much you agree or disagree with each sentence below”, possible answers were on a Likert scale ranging from 1 to 5. The scales demonstrated satisfactory to excellent internal consistency reliability for the considered sample groups, Cronbach alpha values ranged from 0.73 to 0.96 (see Table 1). Having these scales similar characteristics, Chiew and Salim’s (2003 [42]) computation method was adopted for classifying the webpage usability as bad (M range = 1.00–1.80), poor (M range = 1.81–2.60), moderate (M range = 2.61–3.40), good (M range = 3.41–4.20), or excellent (M range = 4.21–5.00).

Qualitative feedback

Open-ended questions were asked in the speakers’ native language to favour reasoning on their experience in navigating the web portal. For conciseness, only the English translation of these questions is reported herein. For students, four questions were asked: (1) “Please, now consult again the webpage […], then indicate any word, phrase, information or function on this webpage that are confusing or hard to understand”; (2) “What other changes would you suggest?”; (3) “What do you like least about this webpage?”; and (4) “What do you like the most about this webpage?”. For teachers and policy makers, three questions were asking: (1) “Please, now consult again the webpage […], then indicate any word, phrase, information or function on this webpage that are confusing or hard to understand”; (2) “Please, explain why the indicated words, phrases, information or functions are confusing or hard to understand”; and (3) “Please, give us some suggestions about where and how you think the webpage could be improved (layout, contents, language, interactive functions, pictures, colours, …)”.

Data analysis

The final sample of 78 students resulted after removing four cases due to incoherent response patterns. No further cases were removed amongst teachers and policy makers’ samples. No missing values were found exploring the dataset.

Quantitative data were analysed, in part, using IBM SPSS 28.0 and, in part, using inbuilt Microsoft Excel features set in the Excel-sheet “Data analysis tool” provided for the UEQ-S (www.ueq-online.org), and graphs were obtained using GraphPad Prism 7.00. Users’ experience when navigating the FitBack web portal was evaluated according to the cut-off scores provided by Schrepp and colleagues (2017 [30]) as updated in the “Data analysis tool” (www.ueq-online.org). Usability of the two webpages was evaluated according to Chiew and Salim’s (2003 [42]) cut-off points. Finally, non-parametric statistical tests were run to observe whether differences existed based on the device utilised when completing the survey.

Qualitative feedback provided by participants was also explored by three authors of the present paper through qualitative content analysis [45]. In a first phase (data preparation), all responses were translated from the participant’s native language to English. In a second phase (forming categories), responses from each participant were examined and words or phrases reminding to Chiew and Salim’s (2003 [42]) dimensions of web usability were highlighted using a deductive approach. In a third phase (coding data), highlighted words or phrases were observed collectively and coded. Codes underpinned by a core concept were reorganised in categories through an inductive approach, and included in a table according to their frequency. This exploration had a twofold purpose, as it allowed having in-depth feedback on possible issues and it also highlighted the most relevant suggestions for the improvement of the website.

Results

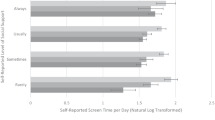

In terms of user experience, the webpage “Make interactive report” was rated on average 5.43 by students and 6.36 by teachers. The webpage “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system” was rated on average 5.99 by policy makers (see Table 1). According to Schrepp and colleagues’ benchmark (www.ueq-online.org [30]), these scores can be considered from good to excellent (see Fig. 2). In terms of usability, the webpage “Make interactive report” was rated on average 3.70 by students and 4.27 by teachers. The webpage “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system” was rated on average 4.13 by policy makers. According to Chiew and Salim’s (2003 [42]) computation method, these scores can be considered good or excellent (see Fig. 2).

With regard to the utilised device, 43 students visited the website and completed the survey using a smartphone, 4 using a tablet, and 31 using a laptop or a PC. Teachers mostly completed the survey via laptop/PC (n = 20) and smartphone (n = 6). Only in one case, the survey was completed using a tablet. All policy makers visited the website and took the survey using a laptop/PC. For students and teachers, Mann–Whitney and the median tests were run to observe if differences existed between the completion of the survey through smartphone or through laptop/PC. In the student sample, statistical tests indicated no significant differences according to the utilised device in terms of user experience (M-W p = 0.77; Me p = 0.90) nor in terms of webpage usability (M-W p = 0.08; Me p = 0.39). Similarly, tests indicated no different distributions (for user experience, p = 0.84; for webpage usability, p = 0.57) or medians (for user experience, p > 0.99; for webpage usability, p > 0.99) between the group of teachers utilising a smartphone and the group utilising a laptop/PC.

Qualitative data analysis helped to recognise the most recurrent words or phrases that were then organised into main categories. Emerged categories were partially consistent with Chiew and Salim’s (2003 [42]) dimensions of web usability, and were labelled: “content”, “design and aesthetic”, “navigability”, “supportability”, “organisation and readability”, “performance and effectiveness”, and “overall”. In Table 2, the frequency of each category for the three different groups of end-users is reported, together with some examples of comments or suggestions given by the participants.

Discussion

Findings from the present evaluation study meet the initial expectations for the FitBack web portal. In fact, the quantitative assessment of the FitBack web portal with students and PE teachers highlighted good-to-excellent user experience when navigating the webpage “Make interactive report”. Similarly, policy makers reported excellent experiences when using the webpage “10 steps to design a physical fitness monitoring system”. These evaluations are based on comparisons which follow a recent benchmark publication for evaluation of similar webpages [30], which is updated annually (www.ueq-online.org). The two webpages also demonstrated ‘good’ or ‘excellent’ usability by all groups of end-users based on the cut-off scores set by the scale authors [42]. There were no significant differences between users when navigating the website through various devices which included smartphone, a tablet, or a laptop/PC.

Qualitative responses also satisfied initial expectations, providing useful cues for the improvement of the web portal and overall positive feedback regarding the two webpages. Content analysis indicated some areas for improvement that were aligned with previous research on web usability [42], specifically: (1) content, organisation and readability; (2) navigation and links; (3) design, aesthetics and attractiveness; and (4) performance and effectiveness. In the present study, it was decided to split the dimension “content, organisation and readability” into two different categories: the category “content” included comments relating to the content and terminology specific for the fitness domain; differently, “organisation and readability” encompassed those comments relating to the general organisation and readability of the website. In terms of “navigation”, students suggested a few modifications to optimise the website for navigation via smartphone. “Design” aspects identified that needed to be improved included a comment from most participants which suggested the platform to incorporate more pictures, videos, and animations. Policy makers suggested adding information online in the “10 step to design …” page which was previously included only in a downloadable pdf file. There were contrasting feedback and opinions regarding web design colours; some participants appreciated the existing colours, whereas others suggested different or brighter colours. A few comments relating to “performance and effectiveness” suggested to simplify some data entry. In addition to these dimensions, the current research found that it would be most useful to label one category “supportability”, intended as “the degree to which the characteristics of the website met the standards of end-users”. This was intended to include a wider number of suggestions, and to make the website available in further languages. Another useful suggestion was to facilitate the choice of the language visually by placing small country flags of the languages available. Finally, the category “overall” was added to the final dimension line-up to include all those comments providing positive feedback about the website as a whole. In fact, qualitative feedback was generally very positive, with many students and teachers stating “I liked everything about this webpage” or “this website is great”. These initial positive experiences led to suggestions that the platform should be translated into more European languages to extend its applicability in different countries.

Implications for practice

The use of appropriate measures for quantitative assessment, the adoption of mixed methods, and the inclusion of real end-users have led us to believe this to be a useful evaluation, rooted in the human–computer interaction theories, and tailored for a specific population [27,28,29]. The approach used in the present study can therefore be replicated in future fitness- or health-related website evaluations.

Moreover, the evaluation described in the present paper has guided the improvement of the FitBack web portal, providing useful critical feedback information relating to PF, PF monitoring and surveillance in youths, and providing meaningful feedback for their teachers or other adults. Such kind of feedback could also help educate relevant adults to the use of adult-reported fitness measures [46], thus making possible to monitor a wide range of population. Further studies should investigate these and other aspects to support the role of PF monitoring and surveillance in improving physical and health literacy.

Aside from the positive evaluation of the website pages and content, it should be noted that new technologies should be developed in combination with other strategies, such as behaviour change techniques, to be most effective at increasing PA levels and PF at the population level and especially in youths [19, 21]. Experiences about PA promotion interventions that combine PF monitoring, new technologies, and behaviour changes techniques are already in place [47]. Results from these studies can provide further evidence for the effectiveness of combined interventions.

Strengths and limitations of the FitBack piloting study

The major strength of the present study is that it utilises a mixed-methods approach for website evaluation [28, 29]. Further strengths of the work are given by the open-sourced categories that emerged from the qualitative questions, which are in line with the previous literature on website usability [42], including that the evaluation was performed on an international sample, indicative of the pan-European nature of the FitBack web portal.

With regard to the sample size, it should be noted that this is a piloting study, that aimed to inform the development of the web portal before its diffusion to a wider public. For the same reason, similar website evaluation study reports a lower number of participants [31, 42]. In the 246 evaluation studies included in Schrepp and colleagues’ [30] benchmark, for instance, the average sample size consisted of 40.26 participants, which is below the number of respondents in the present study.

Beside these strengths, it should be acknowledged the uncertainness about the sample representativeness for the groups of PE teachers and policy makers. In the present study, these two groups were balanced between men and women; however, reliable European data for these two specific categories seem not to be available or not to report gender ratio [44, 48, 49]. Although general teachers in Europe are predominantly women [50], this gender gap may be reduced amongst a specific population of secondary school PE teachers [51]. Nevertheless, further demographic investigations seem still needed in this direction.

Study limitations also include the fact that the number of participants from each nation was too small and unbalanced across countries, thus not allowing for cross-cultural comparisons. Additionally, all participants visited a webpage developed in English and the quantitative parts of the survey were asked in English language, even though English was not all participants’ native language. Although this may have led to some minor issues related to question comprehension, it was decided to focus on actual end-users to avoid biases in the selection of participants. A final limitation regards the website evaluation through different devices: since there was quite a disparity in terms of the number of survey completions via smartphone, tablet or laptop/PC, conclusions on devices are limited.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the FitBack web portal was initially designed to facilitate the combination of bottom–up and top–down approaches to enable fitness monitoring and surveillance systems across Europe to flourish. The present evaluation study allowed researchers and end-users to test the feasibility and usability of the system. The positive responses obtained by this evaluation led the FitBack network to adopt additional languages in its attempt to widen its impact and influence at the European and global level. For future perspectives, youth PF monitoring and surveillance systems should be considered a vital mHealth tool that contributes to children and adolescents’ life-long health. With this in mind, the FitBack web portal represents a useful, flexible, free, and open technology resource for a wide range of end-users.

Data availability

All relevant data from this study will be made available upon reasonable request.

Abbreviations

- PA:

-

Physical activity

- PF:

-

Physical fitness

- mHealth:

-

Mobile health

- PE:

-

Physical education

- PC:

-

Personal computer

- UEQ-S:

-

Short version of the user experience questionnaire

References

Adelantado-Renau M, Esteban-Cornejo I, Mora-Gonzalez J et al (2022) Neurotrophic factors and brain health in children with overweight and obesity: the role of cardiorespiratory fitness. Eur J Sport Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2044912

Joensuu L, Syväoja H, Kallio J, Kulmala J, Kujala UM, Tammelin TH (2018) Objectively measured physical activity, body composition and physical fitness: Cross-sectional associations in 9- to 15-year-old children. Eur J Sport Sci 18(6):882–892. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2018.1457081

Donnelly EJ, Hillman CH, Castelli D et al (2016) Physical activity, fitness, cognitive function, and academic achievement in children: a systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(6):1197–1222. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000901

Álvarez-Bueno C, Hillman CH, Cavero-Redondo I, Sánchez-López M, Pozuelo-Carrascosa DP, Martínez-Vizcaíno V (2020) Aerobic fitness and academic achievement: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Sports Sci 38(5):582–589. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2020.1720496

Sardinha LB, Marques A, Minderico C et al (2016) Longitudinal relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness and academic achievement. Med Sci Sports Exerc 48(5):839–844. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000000830

Corbin CB, Castelli DM, Sibley BA, Le Mesurier GC (2022) Fitness for Life. 7th edn. Human Kinetics

Bouchard C (2019) DNA sequence variations contribute to variability in fitness and trainability. Med Sci Sports Exerc 51(8):1781–1785. https://doi.org/10.1249/MSS.0000000000001976

Tambalis KD, Panagiotakos DB, Psarra G, Sidossis LS (2019) Association of cardiorespiratory fitness levels with dietary habits and lifestyle factors in schoolchildren. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab 44(5):539–545. https://doi.org/10.1139/apnm-2018-0407

Clevenger KA, McNarry MA, Mackintosh KA, Berrigan D (2023) School-Aged Children’s Physical Activity, Adiposity, and Cardiorespiratory and Muscular Fitness. Pediatr Exerc Sci 35(2):99–106. https://doi.org/10.1123/pes.2021-0190

Godoy-Cumillaf A, Fuentes-Merino P, Farías-Valenzuela C et al (2023) The Association between Sedentary Behavior, Physical Activity, and Physical Fitness with Body Mass Index and Sleep Time in Chilean Girls and Boys: A Cross-Sectional Study. Children. https://doi.org/10.3390/children10060981

Maruf FA, Ucheokoye DM (2023) Positive impacts of leisure-time physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness, co-morbidity level, cardiovascular health and quality of life among midlife adults: a cross-sectional study of a Nigerian population. BMC Sports Sci Med Rehabil. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13102-023-00622-6

Migueles JH, Delisle Nyström C, Dumuid D, Leppänen MH, Henriksson P, Löf M (2023) Longitudinal associations of movement behaviours with body composition and physical fitness from 4 to 9 years of age: structural equation and mediation analysis with compositional data. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-023-01417-1

Vani MF, Sabiston CM, Trinh L, Santa MD (2022) Testing the Associations Between Body Image, Social Support, and Physical Activity Among Adolescents and Young Adults Diagnosed With Cancer. Front Psychol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.800314

Ortega FB, Leskošek B, Blagus R et al (2023) European fitness landscape for children and adolescents: updated reference values, fitness maps and country rankings based on nearly 8 million test results from 34 countries gathered by the FitBack network. Br J Sports Med 57:299–310. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2022-106176

Bull FC, Al-Ansari SS, Biddle S et al (2020) World Health Organization 2020 guidelines on physical activity and sedentary behaviour. Br J Sports Med 54(24):1451. https://doi.org/10.1136/bjsports-2020-102955

Lang JJ, Zhang K, Agostinis-Sobrinho C et al (2022) Top 10 international priorities for physical fitness research and surveillance among children and adolescents: a twin-panel Delphi study. Sports Med. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-022-01752-6

Sookermany AM, Sand TS (2019) The physical fitness test discourse model. Cogent Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2019.1615241

Girginov V, Moore P, Olsen N, Godfrey T, Cooke F (2020) Wearable technology-stimulated social interaction for promoting physical activity: a systematic review. Cogent Soc Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1742517

Lee AM, Chavez S, Bian J et al (2019) Efficacy and effectiveness of mobile health technologies for facilitating physical activity in adolescents: Scoping review. J Med Internet Res Mhealth Uhealth. 7(2):e11847. https://doi.org/10.2196/11847

McConnell MV, Turakhia MP, Harrington RA, King AC, Ashley EA (2018) Mobile health advances in physical activity, fitness, and atrial fibrillation: Moving hearts. J Am Coll Cardiol 71(23):2691–2701. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2018.04.030

Schoeppe S, Alley S, Van Lippevelde W et al (2016) Efficacy of interventions that use apps to improve diet, physical activity and sedentary behaviour: A systematic review. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act 13(1):1–26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12966-016-0454-y

LaValley SA, Kiviniemi MT, Gage-Bouchard EA (2017) Where people look for online health information. Health Inf Libr J 34(2):146–155. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12143

Bonnar-Kidd KK, Black DR, Mattson M, Coster D (2009) Online physical activity information: Will typical users find quality information? Health Commun 24(2):165–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410230802676763

Giovanelli A, Ozer EM, Dahl RE (2020) Leveraging technology to improve health in adolescence: A developmental science perspective. J Adolesc Health 67(2):S7–S13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.02.020

Cairney J, Dudley D, Kwan M, Bulten R, Kriellaars D (2019) Physical literacy, physical activity and health: Toward an evidence-informed conceptual model. Sports Med 49(3):371–383. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-019-01063-3

World Health Organisation, WHO. Health literacy development for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Published online 2022. Retrieved 11 Nov 2022. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/364203/9789240055339-eng.pdf?sequence=1

Park E, Kwon M (2018) Health-related internet use by children and adolescents: Systematic review. J Med Internet Res 20(4):e7731. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7731

Issa T, Isaias P (2022) Sustainable Design: HCI, Usability and Environmental Concerns, 2nd edn. Springer, New York

Reen GK, Murhead L, Langdon DW (2019) Usability of health information websites designed for adolescents: Systematic review, neurodevelopmental model, and design brief. J Med Internet Res 21(4):e11584. https://doi.org/10.2196/11584

Schrepp M, Hinderks A, Thomaschewski J (2017) Construction of a benchamark for the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ). Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell 4(4):40–44. https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2017.445

Bailey CM, Seals CD (2017) Evaluation of web usability guidelines for teens. Proc SouthEast Conf. https://doi.org/10.1145/30772863077312

Schrepp M, Hinderks A, Thomaschewski J (2017) Design and evaluation of a short version of the User Experience Questionnaire (UEQ-S). Int J Interact Multimed Artif Intell 4(6):103–108. https://doi.org/10.9781/ijimai.2017.09.001

King AC, Winterb SJ, Chrisingerb BW, Huab J, Banchoff AW (2019) Maximizing the promise of citizen science to advance health and prevent disease. Prev Med 119:44–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.12.016

Castro-Piñero J, Ortega FB, Artero EG et al (2010) Assessing muscular strength in youth: Usefulness of standing long jump as a general index of muscular fitness. J Strength Cond Res 24(7):1810–1817. https://doi.org/10.1519/JSC.0b013e3181ddb03d

Esteban-Cornejo I, Ho FK, Petermann-Rocha F et al (2022) Handgrip strength and all-cause dementia incidence and mortality: findings from the UK Biobank prospective cohort study. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 13(3):1514–1525. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcsm.12857

Ruiz JR, España Romero V, Castro-Piñero J, et al. Batería ALPHA-Fitness: Test de campo para la evaluación de la condición física relacionada con la salud en niños y adolescents. [ALPHA-fitness test battery: Health-related field-based fitness tests assessment in children and adolescents]. Nutr Hosp. 2011;26(6):1210–1214. doi:https://doi.org/10.3305/nh.2011.26.6.5270

Popovic S, Sarmento H, Demetriou Y, Marques A (2021) Editorial: monitoring and promoting physical activity and physical fitness in children. Front Public Health 9:633457. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.633457

Hanssen-Doose A, Niessner C, Oriwol D, Bös K, Woll A, Worth A (2021) Population-based trends in physical fitness of children and adolescents in Germany, 2003–2017. Eur J Sport Sci 21(8):1204–1214. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2020.1793003

Jurak G, Morrison SA, Soric M et al (2022) SLOfit Lifelong: A model for leveraging citizen science to promote and maintain physical fitness and physical literacy across the lifespan. Front Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1002239

Jurak G, Morrison SA, Kovač M et al (2021) A COVID-19 crisis in child physical fitness: Creating a barometric tool of public health engagement for the Republic of Slovenia. Front Public Health. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2021.644235

Morrison SA, Sember V, Leskošek B, Kovač M, Jurak G, Starc G (2021) Assessment of secular trends and health risk in pediatric cardiorespiratory fitness from the Republic of Slovenia. Front Physiol. https://doi.org/10.3389/fphys.2021.644781

Chiew TK, Salim SS (2003) WebUse: website usability evaluation tool. Malays J Comput Sci 16(1):47–57

Eurostat. Archive:Being young in Europe today - demographic trends. Published 2019. Retrieved 21 July 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Archive:Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_demographic_trends

Eurostat. Secondary education statistics. Published 2022. Retrieved 21 July 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Secondary_education_statistics#Teachers_and_pupil.E2.80.93teacher_ratios

Schreier M (2012) Quantitative content analysis in practice. Sage Publications

Sánchez-López M, García-Hermoso A, Ortega FB et al (2022) Validity and reliability of the International fItness scale (IFIS) in preschool children. Eur J Sport Sci. https://doi.org/10.1080/17461391.2022.2049884

Carraro A, Colangelo A, Santi G, Conti C, Petrini M, Gobbi E (2022) An internet-supported continuing professional development training with secondary school physical education teachers: Protocol for the Physical Education for Moving (PE4MOVE) trial. Sustainability 14:11579. https://doi.org/10.3390/su141811579

European Parliament. Briefing November 2016: Physical education in in EU schools. Published online 2016. Retrieved 21 July 2023. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2016/593559/EPRS_BRI(2016)593559_EN.pdf

European Commission, European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Eurydice. Physical education and sport at school in Europe. Published online 2015. Retrieved 21 July 2023. https://data.europa.eu/doi/https://doi.org/10.2797/49648

Eurostat. Teachers in the EU. Published 2020. Retrieved 21 July 2023. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/web/products-eurostat-news/-/edn-20201005-1#:~:text=In%202018%2C%20there%20were%205.2,%25%2C%203.7%20million%20teachers).

Tul M, Leskosek B, Kovac M (2019) The professional competences of physical education teachers from north-eastern Italy. CEPS J 9(1):103–120. https://doi.org/10.25656/01:17108

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to all the participants of this study, as well as to the members of the FitBack network (https://www.fitbackeurope.eu/en-us/partners-and-acknowledgments) for their valuable input to improve the FitBack platform.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Libera Università di Bolzano within the CRUI-CARE Agreement. This research was co-funded by the Erasmus + Sport Programme of the European Union within the project FitBack No. 613010-EPP-1-2019-1-SI-SPO-SCP and the Slovenian Research Agency within the Research programme Bio-psycho-social context of kinesiology No. P5-0142.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization: AC, GS, AlCo and GJ; data curation: AlCo and GS; formal analysis: AC, AlCo, and GS; funding acquisition: GJ; investigation: AC, GS, AlCo, JM, VM, SM, MO, HP and GJ; methodology: AC, GS, AlCo, JM, VM, SM, MO, HP and GJ; project administration: GJ; resources: AC, AlCo and GS; supervision: AC and GJ; visualization: AC and GS; writing—original draft: AC, GS and AlCo; writing—review and editing: AC, GS, SM, and GJ. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest. The funders had and will not have a role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish.

Ethical approval

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the institutional Ethical Committee of Faculty of Sport at the University of Ljubljana, No. 033-11/2021-2.

Informed consent

All participants provided informed consent before entering the research project.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Carraro, A., Santi, G., Colangelo, A. et al. Usability evaluation of the international FitBack web portal for monitoring youth fitness. Sport Sci Health 19, 1363–1373 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-023-01117-0

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11332-023-01117-0