Abstract

Despite longstanding research efforts, there is still ambiguity surrounding the business value created by IT. To approach this conundrum, research focus has progressed from an isolated investigation of IT to the assessment of complementarity between IT and different non-IT resources such as work practices or decision structures. However, incoherence around the characteristics and scope of these complementary non-IT resources has created a fragmented body of research, preventing a sustainable knowledge creation. Thus, in this paper we synthesize the dispersed research efforts, identify shortcomings in the extant literature, and derive opportunities for future research. Specifically, we present a converging definition of complementary non-IT resources and specify their role in the value creation process from IT by viewing it through three distinct lenses: microeconomic theory, resource-based view, and contingency theory. We structure current research efforts by organizing complementary non-IT resources into distinct categories, namely strategy, structure, practices, processes, and culture (organizational resources), top management support, internal relations, and external relations (relational resources), worker skill (non-IT human resources), non-IT physical resources, as well as internal funds and external funds (financial resources). Finally, we highlight five important shortcomings in the current literature, such as the predominant use of reductionist approaches or monolithic IT measures, and make actionable recommendations to resolve them.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

In an era defined by rapidly growing information technology (IT) budgets, it has become paramount for IT executives to create business value from IT (Kappelman et al. 2021). In this context, IT business value (ITBV) is defined as “the organizational performance impacts of information technology at both the intermediate process level and the organization wide level, and comprising both efficiency impacts and competitive impacts” (Melville et al. 2004, p. 287). Yet, only some IT executives are able to accomplish this essential but elusive objective, as there is an increasing divergence in organizational performance across firms that adopt digital technologies (Andrews et al. 2016). Thereby, this dispersion appears to originate from the ability of some firms to exploit complementarities between IT and non-IT resources (Gal et al. 2019).

Naturally, the successful deployment of any IT resource depends on the institutional context surrounding it, as it is embedded in a larger system of interoperating resources (Nadkarni and Prügl 2021). Thus, not only the IT resource itself, but also non-IT resources such as decision structures, worker skills, or supplier relations are pivotal to the successful implementation and utilization of IT (Kohli and Grover 2008; Wade and Hulland 2004). That is why the high rate of abandoned IT projects and the frequently reported inadequate return on IT investments—dating back to the Solow Paradox (Solow 1987)—are not necessarily solely attributable to the IT resource itself, but also to the non-IT resources it interacts with (Doherty et al. 2012; Schweikl and Obermaier 2020). A practical example that illustrates this point is the case of FoxMeyer, which was once the fourth largest distributor of pharmaceuticals in the US. Due to a lack of senior management support and a shortage of skilled workers, the implementation of an enterprise resource planning (ERP) system failed disastrously and ultimately contributed to the firm's bankruptcy (Scott 1999). Hence, non-IT resources can affect the business value created from IT either by completing and thereby enhancing the performance effects or by suppressing some or all of the potential IT-related benefits (Brynjolfsson and Milgrom 2013).

As a consequence, the importance of additional research on the interplay between IT and non-IT resources has been continuously emphasized (Kohli and Grover 2008; Melville et al. 2004; Wade and Hulland 2004), which has cumulated in the emergence of a large body of empirical studies. However, due to the variety of non-IT resources that may act as complements to IT, a fragmented and insulated body of empirical studies has emerged that is comprised of a wide range of different research areas such as strategic IT alignment (e.g. Chan et al. 1997), social alignment (e.g. Wagner et al. 2014), complementary investments to IT in work practices (e.g. Bresnahan et al. 2002), IT and decision structures (e.g. Andersen and Segars 2001), or IT-associated process-reengineering (e.g. Devaraj and Kohli 2000).

Surprisingly, there is no comprehensive review that synthesizes and integrates these important but dispersed research streams to obtain a holistic view on resource complementarity in ITBV research. While Wiengarten et al. (2013) reviewed the literature regarding complementary organizational resources, they did not consider human or relational aspects, although their pivotal role in the value creation process from IT has been explicitly highlighted (Grover and Kohli 2012; Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997). Further, scholars call for more research on the role of complementary non-IT resources in the value creation from IT (Chae et al. 2014; Piccoli and Lui 2014) as well as advocate for a classification of complementary non-IT resources to structure the research field and enable a sustainable knowledge creation (Kim et al. 2011).

Thus, we seek to address these research needs and utilize the gained knowledge to translate shortfalls in our current understanding of resource complementarity into opportunities for future research (Rowe 2014). Consequently, we aim to answer the following research questions: (1) What is the role of complementary non-IT resources in the value creation from IT? (2) What complementary non-IT resources have been empirically investigated so far and how can they be categorized? (3) What are shortcomings in the current literature and how can they be resolved?

To approach our research questions, we systematically reviewed 227 articles from a broad range of academic journals in the business field. In doing so, we make three important contributions to the ITBV literature: first, we present a converging definition of complementary non-IT resources. Second, we develop a systematic classification of complementary non-IT resources, including strategy, structure, practices, processes, and culture (organizational resources), top management support (TMS), internal relations, and external relations (relational resources), worker skill (non-IT human resources), non-IT physical resources, as well as internal and external funds (financial resources). Building on this classification, we also organize current empirical research efforts to obtain insights on the relationship between IT and specific non-IT resources. Third, we highlight five shortcomings in the existing literature and present actionable solutions to develop an agenda for future research efforts. In particular, we show that research has so far focused on reductionist approaches, leading to a major knowledge gap regarding different configurational recipes of IT and complementary non-IT resources that are sufficient to attain desired performance outcomes.

The remainder of this article is structured as follows: in the next section, we present a definition and classification of complementary non-IT resources. In Sect. 3, we outline the different theoretical lenses used to describe the role of complementary non-IT resources in the value creation process from IT and provide an integrative framework on complementarity in ITBV research. In Sect. 4, we detail our systematic review process. In Sect. 5, we organize empirical research efforts according to our classification of complementary non-IT resources and shed light on the complementarity of certain IT and non-IT resources. In Sect. 6, we highlight shortcomings in the extant literature and suggest avenues for future research. In Sect. 7, we make some concluding remarks.

2 Conceptualizing complementary non-IT resources in ITBV research

2.1 Definition of complementary non-IT resources

Two or more input factors or activities are complementary when “doing (more of) any one of them increases the returns to doing (more of) the others" (Milgrom and Roberts 1995, p. 181). Thus, the economic value generated by the combination of two or more complementary input factors or activities surpasses the value that would be created by utilizing them in isolation (Milgrom and Roberts 1990, 1994). Thereby, empirical evidence suggests that complementarities among heterogeneous resources are particularly powerful performance drivers (Ennen and Richter 2010).

While it is possible to implement IT with minimal organizational changes, the successful introduction of an IT system is often associated with a fundamental organizational transformation (Hammer 1990). Thus, the success of an IT investment seems not only to depend on the investment itself, but also on the non-IT resources it’s surrounded by (Davern and Kauffman 2000). In this regard, a firm’s ability to create business value by combining IT resources with non-IT resources is referred to as IT complementarity (Masli et al. 2011).

Although a variety of conceptual works have stressed the importance of complementary non-IT resources in the value creation form IT (Brynjolfsson and Hitt 2000; Cao et al. 2016; Kohli and Grover 2008; Melville et al. 2004; Wade and Hulland 2004; Wiengarten et al. 2013), there is still incoherence surrounding the concept of IT complementarity. While some studies have addressed organizational aspects (Clemons and Row 1991; Wiengarten et al. 2013), others have highlighted the importance of human resources (Brynjolfsson and Hitt 2000), and yet others focus on relational arrangements as a key piece to create value from IT (Grover and Kohli 2012; Kohli and Grover 2008). This diverging research focus has resulted in dissent on the scope and characteristics of complementary non-IT resources and lack of a converging definition that encompasses the varying resource dimensions (see Table 1 for an overview of important conceptual works). Despite the long-standing ambiguity, hardly any new conceptual work has emerged in recent years to address this issue. Consequently, we approach this research need by devising a comprehensive definition of complementary non-IT resources based on established resource dimensions.

Resources are generally seen as all assets, capabilities, knowledge, etc. within a firm (Barney 1991). Expanding this perspective, researchers have proposed that firm resources are also able to span organizational boundaries and are embedded in the relationships with external organizational partners (Lavie 2006; Zander and Zander 2005). Although firms do not possess resources outside of firm boundaries, they may be able to access and leverage some of them to enhance the value of intra-firm resources (Lavie 2006). Thus, it is not sufficient to solely consider resources within a firm, but also between firms, to achieve a more exhaustive view on IT complementarity (Grover and Kohli 2012). There are, however, environmental factors outside an organization that a firm has no influence on including government policies, national culture, legislation, or certain industry characteristics, which have to be delineated from the concept of intra- and inter-firm resources (Wade and Hulland 2004).

Besides the intra- und inter-firm setting, resources are often grouped into tangible and intangible ones (Barney 1991; Grant 1991). Tangible resources are generally visible and can be quantified. They include physical resources like machines, equipment, and the location of the firm as well as financial resources (Grant 1991). Intangible resources encompass immaterial assets and can be divided into (Grant 1991; Musiolik et al. 2012): (1) Organizational resources, which characterize the setting in which employees have to work and include structure, practices, culture, etc. (2) Relational resources, which reflect the relations within a firm and between firms. These include, for example, interactions between employees in different departments or customer relations. (3) Human resources, which are comprised of the skills, knowledge, and experience of employees. (4) Technological resources, which span non-physical assets such as business applications or databases.

These resource dimensions can be further differentiated into those that pertain to IT resources and those that do not. Thereby, IT resources are comprised of technical IT resources including IT infrastructure like hardware assets (IT physical resources), business applications like an ERP system (technology resources), as well as human technical skills and IT managerial skills (IT human resources) (Melville et al. 2004). The remaining resources can in turn be categorized as non-IT resources and divided into organizational resources, relational resources, non-IT human resources, non-IT physical resources, and financial resources.

In the light of this characterization of non-IT resources and the notion that complementarity between IT and non-IT resources amplifies the business value created by them (Milgrom and Roberts 1995), we define complementary non-IT resources as organizational resources, relational resources, non-IT human resources, non-IT physical resources, and financial resources within and between firms that magnify the impact of IT resources on organizational performance at the intermediate process level or organization wide level.

2.2 Classification of complementary non-IT resources

Besides a definition of complementary non-IT resources, a granular classification of complementary non-IT resources must also be established in order to systematically analyze empirical results and gain insights regarding the existence of complementarities between IT and certain non-IT resources. Accordingly, we developed—based on a careful review of prior suggestions of complementary non-IT resources categories (see Table 1) and an examination of studies that define specific resource categories common to all organizations (e.g., Chandler 1962; Mintzberg 1979)—a comprehensive classification of complementary non-IT resources (see Table 2).

In doing so, we further disaggregate complementary non-IT resources into the following distinct categories: (1) Organizational resources contain the business strategy of a firm (Chandler 1962), structure (Mintzberg 1979), practices (Gibson et al. 2007), processes (Davenport and Short 1990), and culture (Schein 1985), (2) relational resources can be further split into TMS (Igbaria et al. 1997), internal relations between individual, groups, or departments and external relations with other parties beyond organizational boundaries (Ray et al. 2013), (3) non-IT human resources reflect the worker skill not directly related or limited to technical abilities (Bresnahan et al. 2002), (4) non-IT physical resources contain material assets not related to physical IT assets, such as mechanical equipment (Melville et al. 2004), and (5) financial resources represent the access to internal and external funds (Chatterjee and Wernerfelt 1991).

3 Theoretical background and an integrative framework of complementarity in ITBV research

3.1 Theoretical underpinnings used in research on complementarity in ITBV

Having outlined the characteristics and scope of complementary non-IT resources, the question still remains as to what role they play in the value creation process from IT. Researchers have applied several theoretical frameworks to answer this question, whereby three particularly prevalent theoretical lenses have emerged: microeconomic theory, resource-based view (RBV), and contingency theory (Oh and Pinsonneault 2007). Although, these theories are not mutually exclusive in many respects—as reflected by the fact that a variety of studies span multiple theoretical underpinnings (e.g. Schwarz et al. 2010; Tanriverdi 2005)—each has a different perspective on the mechanisms to create value from IT and the conditions under which ITBV emerges (see Table 3). Therefore, we examine each theory to gain a more profound understanding on the role of complementary non-IT resources in the business value creation from IT.

3.1.1 Microeconomic theory

On a firm level, the economic theory of production is generally applied to specify the contribution of different inputs to output. Inputs include non-IT capital and non-IT labor as well as IT capital and IT labor, whereas output is reflected by sales or sales per employee (labor productivity). Based on the assumption of a certain production function, the contribution of input factors to the output can be measured econometrically. Given this economic relation, IT is regarded as a technology that has a dual influence on productivity. On the one hand, IT can directly improve productivity via the automatization of business processes by increasing IT capital relative to labor input and, on the other hand, indirectly by facilitating the flow of information within and between firms. This entails the potential to more efficiently combine the different input factors by restructuring work flows and business processes (Dedrick et al. 2003). To assess the impact of IT on productivity, the gross marginal product, defined as the increase in output for the last dollar spent on the input, is estimated. Rational managers should keep investing in IT, until an additional unit of the input creates no more value than its costs, leading to a net marginal product of zero. Apart from some early studies, empirical evidence suggests that IT investment yields not only a positive gross marginal product, but even a positive net marginal product (see Schweikl and Obermaier 2020).

Brynjolfsson and Hitt (2000) argue that this phenomenon is caused by complementary investments to IT like business process reengineering or the introduction of new work practices, which are not accounted for as part of the IT investment but enhance productivity growth. Therefore, some firms seem to retrieve excessive returns from their IT investment by combining it with complementary investments. Thus, a group of complementary inputs or activities needs to be adopted, when IT is implemented, as this will increase its marginal return (Milgrom and Roberts 1990). Consequently, when a firm adopts IT resources, the economic incentive to invest in a system of different complementary non-IT resources increases (et vice versa), as they are mutually reinforcing (Brynjolfsson and Hitt 1998, 2000).

3.1.2 Resource-based view

The RBV has become the most widely used theory to underpin resource complementarity in ITBV research. It assumes that firms possess different resources that are heterogeneously distributed among firms (Barney 1991; Penrose 1959; Wernerfelt 1984). Barney (1991) states that resources must be valuable, rare, inimitable, and non-substitutable (VRIN conditions) to be the source of a sustainable competitive advantage. However, it has been argued that resources are rarely productive by themselves and can generally be traded on factor markets, rendering them susceptible to imitation (Amit and Schoemaker 1993). Thus, researchers have begun to argue that economic rent depends primarily on the capabilities that emerge from the interplay between resources, as they reside in the routines of firms, which makes them difficult to imitate due to their idiosyncratic and intangible nature (Amit and Schoemaker 1993; Grant 1991; Teece et al. 1997). Thereby, resources can have either a compensatory, complementary, or suppressive relationship (Black and Boal 1994). A compensatory relationship arises when a variation in the level of one resource is offset by a change in the level of another resource. A suppressive relationship exists when the presence of one resource decreases the effect of another resource. A complementary relationship exists when a resource amplifies the impact of another resource. Therefore, it is critical for organizations to create a complementary resource bundle and mobilize these resources in combination in order to develop capabilities that can be the basis of a sustainable competitive advantage (Grant 1991, 1996).

Nonetheless, if IT resources by themselves are able to satisfy the VRIN conditions, they could be the basis of a sustainable competitive advantage. Technological IT resources are mostly recognized as valuable, because they reduce the cost of coordinating economic activities, but are generally neither rare nor inimitable or non-substitutable (Mata et al. 1995). There may be some cases where firms own software that is proprietary and therefore rare, leading to a possible short-term competitive advantage. Yet, factors like workforce mobility, reverse engineering, or alliances reduce the secrecy of proprietary technology and lead to imitation or substitution of the technology (Clemons and Row 1991; Mata et al. 1995). However, by combining technological and human IT resources, firms may be able to achieve a competitive advantage. By adapting standardized software and hardware offerings with the help of IT specialists, companies can gain an advantage over their competitors, as this is usually a difficult to imitate procedure (Mata et al. 1995). With the rapidly growing IT service offerings, human technical skills and IT managerial skills can, however, be obtained externally, which makes such an advantage often times only short-lived (Melville et al. 2004). Consequently, it has been argued that IT resources have become a necessity to compete, but cannot be the source of a sustainable competitive advantage on their own (Piccoli and Lui 2014).

Even though IT resources alone may not affect firm performance, researchers have suggested that by combining them with complementary non-IT resources firms are able to satisfy the VRIN conditions (Clemons and Row 1991; Melville et al. 2004; Piccoli and Ives 2005; Wade and Hulland 2004). As resource synergies are protected by path dependencies and social ambiguity due to the complexity of combining heterogeneous resources, the complementary interplay between IT and non-IT resources can create a sustainable competitive advantage and increased economic rents (Aral and Weill 2007).

3.1.3 Contingency theory

According to Burns and Stalker (1961), there is no single best management system every firm can or should follow, but rather an optimal management system depends on a variety of factors within and outside the firm. Grounded in this idea, contingency theory assumes that firm performance depends on the fit or alignment between two or more factors (Donaldson 2001; Drazin and van de Ven 1985; Venkatraman 1989b). Thereby, fit can be defined as “the degree to which the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures of one component are consistent with the needs, demands, goals, objectives, and/or structures of another component” (Nadler and Tushman 1980, p. 45).Footnote 1

Accordingly, studies typically measure business-IT alignment as a state of congruence, i.e. the extent to which an IT resource supports or conforms to a given non-IT resource. A higher level of alignment between IT and other factors should lead to a better firm performance, whereas a low level of fit should result in dysfunction and low firm performance (Weill and Olson 1989). There are, however, different types of fit. Venkatraman (1989b) propose six different perspectives: fit as moderation, fit as mediation, fit as matching, fit as profile deviation, fit as covariation, and fit as gestalts. Building on these insights, Umanath (2003) specifies the concept of fit in IS research and divides it into a congruence, contingency, and holistic perspective. Fit as congruence proposes that IT is linked to factors without evaluating, if this interaction has an effect on firm performance. Fit as contingency evaluates a pairwise interaction (bivariate fit) between IT and a single factor. Fit as holistic configurations explores interdependencies between IT and a system of factors (system fit).

When contingency theory is applied to understand the performance effects of interactions between IT and non-IT resources, research seems to have predominantly focused on bivariate fit. Thereby, particularly the relation between IT and strategy has received considerably research interest. The concept of aligning IT and business strategy is grounded in the strategic alignment model (SAM) (Henderson and Venkatraman 1993). According to this model, firm performance is determined by the degree of alignment and integration among a firm’s business strategy, IT strategy, business infrastructure/processes, and IT infrastructure/processes. Thereby, the infrastructure/processes dimension encompasses policies, procedures, employees, structure, systems, and activities (Henderson and Venkatraman 1993). Surprisingly, although the SAM model illustrates a system fit perspective, as it proposes the need for cross-domain alignment, subsequent empirical research efforts have mostly utilized bivariate fit approaches to assess the model (Gerow et al. 2015).

3.2 Integrative framework of complementarity in ITBV research

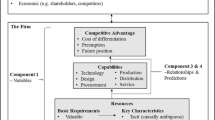

In summary, analyzing the prevailing theoretical lenses reveals that the value creation from IT does not only depend on the IT resource itself but rather on the institutional context it is surrounded by (see Fig. 1).

IT should not be viewed as an isolated resource that leads to substantial increases in firm performance on its own. Instead, firms can enhance the value of IT by combining it with complementary non-IT resources or may only be able to achieve any performance improvements at all, if the IT resource fits the specific organizational context to prevent a dysfunctional resource system (Weill and Olson 1989; Milgrom and Roberts 1990). Beyond that, the establishment of a synergistic resource system of IT and non-IT resources is difficult to duplicate, because it cannot be directly observed and replicating only part of the system is tantamount to an incomplete system, which is more likely to deteriorate a competitor’s performance than improve it (Aral and Weill 2007). Thus, the attainment of a synergistic system of IT and non-IT resources is subject to asset stock accumulation and organizational learning processes, which creates a strong barrier to imitation (Piccoli and Ives 2005). Therefore, it is critical for organizations to create an effective resource system by accumulating the required IT and non-IT resources as well as mobilizing these resources in combination in order to achieve improved performance (Bharadwaj 2000).

In this context, performance comprises process performance as well as firm performance (Dedrick et al. 2003; Melville et al. 2004; Schryen 2013), whereby the former functions as an intermediary factor. Process performance refers to a set of measures associated with specific business processes, such as increased flexibility, improved customer service, or reduced cycle times related to inventory management (Melville et al. 2004). In contrast, firm performance denotes performance across all firm activities and is mostly measured by using indicators related to accounting performance (e.g. profitability), market performance (e.g. market value), and productivity (e.g. labour productivity) (Schryen 2013). However, the range of potential measures is not limited to tangible performance metrics and may include intangible performance measures, such as innovation performance (Grover and Kohli 2008).

Additionally, the effects of the interaction between IT and non-IT resources on performance may also be influenced by environmental factors, such as the intensity of competition (Melville et al. 2004; Wade and Hulland 2004). Hence, our model also includes the moderating role of environmental factors.

At the same time, while the presented theoretical frameworks outline mechanisms for achieving performance improvements through IT and specify the role of complementary non-IT resources in the value creation process from IT, they offer no insights regarding the existence of complementary relationships between certain IT and non-IT resource or the conditions under which they are formed (Ennen and Richter 2010). As a consequence, when studies consider the interactions between specific IT and non-IT resources to be complementary, this is usually based on ex post empirical evidence. However, there is no work that synthesizes and integrates these empirical findings, which impedes meaningful progress in this domain (Kim et al. 2011). Thus, an eminent research need and key objective of our review of empirical studies is to inductively gain insights on non-IT resources that have been observed to complement IT resources and the conditions under which such complementary effects emerge.

4 Research methodology

In accordance with the established procedures in this research domain (Fisch and Block 2018; Tranfield et al. 2003; Webster and Watson 2002), we began by defining a detailed scope of our review.

In our review we seek to investigate whether the impact of IT resources on business value is enhanced or suppressed by the presence of certain non-IT resources. This is consistent with a moderating perspective and also referred to as the contingency or complementary approach (Benitez-Amado and Walczuch 2012). In accordance with this perspective, we applied five selection criteria for our literature sample. First, we only considered studies that investigate the relation between IT and business value. For this criterion, we adopted the IT conceptualization suggested by Kohli and Grover (2008), which encompasses not only the components of IT but also more generic concepts, such as “IT capability”. To achieve a comprehensive depiction of the research field, we interpret IT components in a broad sense that encompasses not only hardware and software, but also telecommunications (Dedrick et al. 2003). Thus, we also included studies that use information and communication technology (ICT) as a dependent variable. Second, a study had to address at least one complementary non-IT resource. Thereby, we only considered complementary non-IT resources that are intangible (organizational resources, relational resources, and non-IT human resources), as they are more likely than tangible resources to confer a competitive advantage and thus particularly important in creating value from IT (Saunders and Brynjolfsson 2016). In order to provide an encompassing coverage of this research field, we also considered studies that use direct measures to determine the congruence between IT and non-IT resources (e.g. Karahanna and Preston 2013). Third, following the definition of ITBV by Melville et al. (2004), we only included studies in our review that examine organizational performance at the process or firm level. Hence, we focus on studies at the microeconomic level. In addition to tangible performance indicators, which can be calculated using financial statements (e.g. return on investment) or process data (e.g. production time), we also took into account intangible business value dimensions such as customer relationship performance (Trainor et al. 2014). Fourth, to maintain a methodologically comparable literature base, we only considered quantitative empirical works, as qualitative ones (e.g. case studies) use distinctly different data sets and research methods. Fifth, an article had to be written in English.

After specifying the scope of our review, we adopted the search approach outline by Webster and Watson (2002) to retrieve our literature sample. To identify relevant studies, we carefully examined the title, abstract, or, if necessary, the full text of an article to assess whether it meets all of the five predefined criteria. In our first step, we performed a keyword searchFootnote 2 (in title, subject headings, and abstract) utilizing the Business Source Premier Database, which constitutes a comprehensive database for articles in the fields of business and economics. The search was restricted to academic, peer-reviewed journal articles in English language published until the 30th of April 2022. This resulted in an initial sample of 3056 articles. Thereof, 2929 articles were excluded due to: no inclusion of a complementary non-IT resource, no association of complementary relationships with process or firm level performance (e.g. Bartel et al. 2007), examining complementary non-IT resources as antecedents of IT use, adoption, alignment, investment, or diffusion (e.g. Kawakami et al. 2015), no assessment of complementarity between IT and non-IT resources (e.g. Black and Lynch 2001), and the investigation of complementarity between different types of IT resources (e.g. Sanders 2005; Zhu 2004). Thus, we obtained 127 studies by keyword search.

In a second step, we screened the tables of contents of the eight journals that are part of the IS Senior Scholars' Basket of Journals: European Journal of Information Systems, Information Systems Journal, Information Systems Research, Journal of the Association for Information Systems, Journal of Information Technology, Journal of Management Information Systems, Journal of Strategic Information Systems, and MIS Quarterly (AIS 2011). We made one more addition to this set of journals and included Information & Management, because this journal is known to publish important research on IT value (Palvia et al. 2017). In doing so, we identified an additional 45 studies.

In a third step, we conducted a backwards search by screening the bibliographies of our identified studies. Working papers or conference papers were not considered due to their preliminary stage. Moreover, we did not consider any books or book chapters due to the difficulty of assessing their academic rigor. Overall, we obtained an additional 23 studies.

In a fourth step, we performed a forward search. The Web of Science database was used to retrieve articles citing the studies collected so far, which led to the addition of another 29 articles.

In a fifth step, we scanned the references of prior reviews and meta-analyses in the field of ITBV (Gerow et al. 2014; Mandrella et al. 2020; Sabherwal and Jeyaraj 2015; Schryen 2013; Wiengarten et al. 2013) to ensure that we did not miss any relevant articles. This resulted in the inclusion of three papers and a final sample of 227 studies.

An overview of the identified studies is provided in Online Appendix A. The overview contains information for each study on the dataset used, the consideration of environmental factors, the adopted theory, the method applied to examine complementarities, and the non-IT resources that were examined.

5 The state of resource complementarity in ITBV research

To organize research on complementary non-IT resources and gain deeper insights regarding their relationship with IT resources, we categorized the identified papers according to our classification of complementary non-IT resources (see Table 2). Because some papers examine multiple complementary non-IT resources, a study can be assigned to more than one category. We utilized the measure (e.g. the different survey items) of the complementary non-IT resource in each study to determine the appropriate category. Thereby, we were able to classify all studies in at least one of the suggested categories (see Online Appendix A), which further validates our proposed classification of complementary non-IT resources.

5.1 Strategy

Strategy can be understood as the identification of a company's long-term objective, adoption of courses of action, and allocation of resources required to accomplish these goals (Chandler 1962). We identified 104 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with strategy, making this by far the largest research field. Thereby, studies use a broad range of fit perspectives: matching (e.g. Gómez et al. 2016), moderation (e.g. Tallon and Pinsonneault 2011), profile deviation (e.g. Sabherwal et al. 2019), covariation (e.g. Chatzoglou et al. 2011), or gestalts (e.g. Pollalis 2003). While most studies are at the firm level, in recent years a shift towards more process-level studies has taken place (e.g. Tallon 2008, 2012; Tallon et al. 2016). Also, a variety of scales or proxies are applied to measure alignment between IT and business strategy such as Venkatraman’s (1989a) Strategic Orientation of Business Enterprises (STROBE) and/or Chan’s et al. (1997) Strategic Orientation of the Existing Portfolio of Information Systems (STROPIS) scale (e.g., Sabherwal and Chan 2001), Miles and Charles’s (1978) defenders, prospectors, and analyzers typology (e.g. Croteau and Bergeron 2001), Treacy and Wierseman’s (1995) value disciplines typology (e.g. Tallon 2008), Porter’s (1980) generic business strategies (e.g. Yin et al. 2020), or fit/integration between business and IT plan (e.g. Kearns and Lederer 2004).

For all the different strategy measures, fit perspectives, and observation levels, the studies included in our sample consistently support that the alignment between IT and business strategy improves firm performance (see also Gerow et al. 2014). For instance, Chan et al. (1997) find a positive effect of strategic IT alignment on perceived IS effectiveness and perceived firm performance. Likewise, Wu et al. (2015) show a positive link between realized strategic IT alignment and organizational performance. At times, studies report mixed results with strategic IT alignment only impacting some performance aspects (e.g. Croteau and Bergeron 2001), affecting performance only when specific business strategies are pursued (e.g. Chan et al. 2006), only when certain fit perspectives are utilized (e.g. Cragg et al. 2002), or only at certain observation levels (e.g. Queiroz 2017). Seldom studies also offer contradictory results. For instance, Palmer and Markus (2000) demonstrate that retail firms with a matched IT and business strategy do not perform significantly better than those with an un-matched IT and business strategy.

5.2 Structure

The structure of an organization can be defined as “the sum total of the ways in which it divides its labor into distinct tasks and then achieves coordination among them” (Mintzberg 1979, p. 2). We identified 44 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with structure. Organizational structure spans multiple sub-categories including formalization (emphasis on formal rules), specialization (number of distinct job titles), functional differentiation (number of departments), centralization (employee participation in decision making), professionalization (percentage of professional staff members), and vertical differentiation (number of hierarchical levels) (Damanpour 1991). While some studies investigate the alignment of IT resources with different sub-categories of structure (Bergeron et al. 2001, 2004; Buttermann et al. 2008; Chatzoglou et al. 2011; Raymond et al. 1995), the predominant research focus is on the relationship between IT and (de-)centralization.

While IT enables enterprises to process and transfer ever-larger amounts of data, boundedly rational organizations are constrained in the amount of information they can effectively absorb (Tambe et al. 2012). As employees can only process a limited amount of information, too much input can lead to an information overload and negatively affect performance (Andersen 2005). In order to circumvent this phenomenon, firms must improve information flow within an organization (Bresnahan et al. 2002). This can be achieved by an increase in lateral communication and a stronger reliance on decentralized decision-making by flattening hierarchies and granting more decision power to individual workers (Bertschek and Kaiser 2004).

However, the empirical evidence regarding the complementarity between IT and a decentralization is ambiguous. While some studies indicate a synergistic relationship (Albadvi et al. 2007; Brynjolfsson et al. 2002; Francalanci and Galal 1998) or a negative interaction between centralization and IT (Fink and Sukenik 2011), others find no significant interaction effect between IT and decentralization (Andersen and Segars 2001; Arvanitis 2005; Arvanitis and Loukis 2009; Arvanitis et al. 2016; Bertschek and Kaiser 2004; Caroli and van Reenen 2001; Dostie and Jayaraman 2012; Moshiri and Simpson 2011; Rasel 2016) as well as mixed results (Commander et al. 2011; Mohamad et al. 2017), while yet others even indicate a suppressing relationship (Giuri et al. 2008). Thus, it appears that IT resources are not per se complementary to a decentralized decision structure.

5.3 Practice

Practices are “policies, programs, or systems that encourage or allow certain behaviors” (Gibson et al. 2007, p. 1467). We identified 56 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with practices. Thereby, studies focus mostly either on human resource practices including promoting teamwork (e.g. Bresnahan et al. 2002), job rotation (e.g. Stucki and Wochner 2019), flexible working arrangements (e.g. Moshiri and Simpson 2011), hiring (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2002), worker training (e.g. Prasad and Heales 2010), incentive systems (e.g. Aral et al. 2012), and worker monitoring (e.g. Commander et al. 2011) or externally focused practices such as benchmarking (e.g. Tambe et al. 2012), supplier management (e.g. Vickery et al. 2010), and customer involvement initiatives (e.g. Saldanha et al. 2017).

The introduction of IT can lead to a shift in the role of employees and to a redeployment of workers who have to be flexible and take on new tasks. Given these alterations due to IT adoption, firms may have to implement new guidelines for hiring, promoting, firing, and training their workers. Bloom et al. (2012) conclude that US-lead companies in Europe deploy IT more productive than European ones due to a more pro-active human resources management, which is characterized by faster promotions of high-performers but also quicker layoffs of below-average employees.

In addition, with the implementation of IT it becomes easier for firms to monitor the performance of employees. By combining data on workflows, financial transactions, etc. with human resource data, executives are able to align the tasks of employees with the overall business strategy, assessing the demand they put on employees as well as keeping track with their performance (Aral et al. 2012). Therefore, IT can support executives in monitoring and evaluating employee performance, which facilitates performance-based incentive systems and assists in directing employees’ efforts towards the objectives of the firm. For instance, Aral et al. (2012) indicate that the adoption of human capital management software is associated with a substantial productivity increase when it is implemented in combination with performance pay and human resource analytics practices.

Besides, companies may also have to adopt new externally focused practices. As IT enables firms to have closer relations with external partners and process large external information streams, firms may need to implement practices that take advantage of these new possibilities. For example, Tambe et al. (2012) indicate that the combination of externally focused, decentralization, and IT enhances firm performance more than the sum of their separate effects.

5.4 Process

Processes are a set of defined activities or tasks to achieve distinct business outcomes (Davenport and Short 1990). We identified 46 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with processes. The research scope ranges from studies that investigate firm-wide process reengineering (e.g. Albadvi et al. 2007) to studies that focus on specific types of organizational processes such as knowledge management processes (e.g. Tanriverdi 2005), production processes (e.g. Ward and Zhou 2006), relational processes (e.g. Reinartz et al. 2004), and supply chain processes (e.g. Liu et al. 2016).

As IT facilitates the flow of information within and between firms and reduces the cost of coordinating business activities, it enables a transformation of business processes (Grover et al. 1998). Thus, with the adoption of IT, firms may need to re-engineer processes or couple IT with existing processes to realize its business value. Thereby, some studies suggest that the alignment of IT and organizational processes directly improves firm performance. For example, Devaraj and Kohli (2000) indicate that joint adoption of business process re-engineering and IT investment leads to improved profitability for hospitals. Similarly, Ramirez et al. (2010) find that a significant improvement of firm productivity and market value from business process re-engineering only appears when it is implemented in combination with IT.

Others propose that the synergistic relationship between IT and organizational processes affects firm performance indirectly via the emergence of IT-enabled organizational capabilities. For instance, Tanriverdi (2005) demonstrate that the interplay between IT infrastructure and different management processes enables knowledge management capabilities, which ultimately improve firm performance. Bendoly et al. (2012) show that information system (IS) capabilities enhance the effect of manufacturing-marketing process coordination and manufacturing-supply chain process coordination on market intelligence and supply-chain intelligence, which in turn increase new product development performance.

5.5 Culture

Culture reflects the shared values, ideals, and convictions of organizational members, which manifest themselves in their behavior (Schein 1985). We identified 19 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with culture.

Culture is an elusive concept that is hard to observe and requires the concurrent manipulation of complex human relationships and technologies, which makes it difficult to re-create and a powerful source of competitive advantage (Powell and Dent-Micallef 1997). For instance, an open communication culture is often seen as complementary to IT as it facilitates knowledge exchange between employees and encourages closer cooperation of functional departments within an organization, resulting in more interdisciplinary and innovative solution approaches (Jeffers et al. 2008). Supporting this assertion, Ifinedo (2007) find that firms with an culture marked by information sharing and collaboration have higher ERP system success. However, Fawcett et al. (2011) show that investments in either supply chain connectivity or an information-sharing culture among supply chain members enhance operational performance and customer satisfaction, but there is no mutual reinforcement.

Another aspect that has received research attention is an organizational culture that promotes the support and empowerment of employees (Gold et al. 2001; Kmieciak et al. 2012). Encouraging employees to interact, utilize their creativity, and increase their initiative to peruse innovative ideas, can create a sense of ownership and contribution among employees. Kmieciak et al. (2012) find that IT capability positively moderates the relation between employee empowerment and firm performance of small and medium enterprises, even suggesting that a corporate culture that promotes employee empowerment without the adoption of IT might negatively affect firm performance.

Furthermore, a clear vision or commitment of an organization is needed to unify employees and develop an organizational purpose to direct resources and efforts towards a shared goal. For instance, Bradley et al. (2006) observe that the quality of the IT plan has a greater impact on IS success in enterprises that possess an entrepreneurial culture with a commitment to innovation than in those that exhibit a more formal and bureaucratic culture.

5.6 Top management support

TMS reflects the “level of general support offered by top management […]” (Igbaria et al. 1997, p. 289). We found 22 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with TMS.

Top management generally has an excellent oversight of the entire organization, which enables them to identify the areas where IT resources are required and can be adequately leveraged to add value to the business. Thus, managers should play a central role in planning the long-term orientation of the IT investment and be continuously involved in IT projects to ensure an effective and efficient utilization of IT resources. While some studies indicate that TMS enhances the impact of IT resources on organizational performance (e.g. Cohen 2008; Kearns and Sabherwal 2007), others suggest that a more nuanced perspective is needed. In particular, Weill (1992) shows that top management commitment increases the contribution of strategic IT investment to business performance. For transactional and informational IT investments, he finds, however, no significant moderation effect. Steelman et al. (2019), who divide IT into current IT investments and new IT investments, are able to show that organizational commitment to IT increases the marginal benefits of current IT investments for firms that pursue a defender strategy, but it decreases the marginal benefits, if they invest in new IT systems. They also find that the contrary is true for firms that pursue a prospector strategy. In sum, while TMS appears to be an important complement to IT resources, it seems that its importance varies depending on the relevance of the IT resource for a given business strategy.

5.7 Internal relations

Internal relations describe individuals, groups, or departments collaborating across intra-organizational boundaries. We identified 30 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with internal relationships. Thereby, the alignment between IT and non-IT personal is often referred to as social alignment (Reich and Benbasat 2000) and has been analyzed at various aggregation levels, such as between individuals (e.g. Jeffers 2010), groups (e.g. Lee et al. 2008), or departments (e.g. Oh et al. 2014) as well as varying hierarchical levels like ties between line managers (e.g. Jeffers 2010) or Chief Information Officer (CIO) and Chief Executive Officer (CEO) (e.g. Li and Ye 1999).

Close relations between IT and business functions are vital to enable mutual trust and encourage the sharing of resources to jointly create value (Wagner et al. 2014). When employees are more closely connected, they are more inclined to openly discuss problems and support another (Schlosser et al. 2015). By means of such an effective communication, employees share a common understanding of the role of IT within the organization, and IT professionals are able to identify and address the IT needs of an organization (et vice versa). Conversely, if there is mistrust between the IT and non-IT personal, informal contacts will be avoided, which may affect firm performance negatively as it hinders information sharing (Ray et al. 2005). Accordingly, Wagner et al. (2014) observe that mutual trust and respect between IT and business units has a positive effect on the business understanding of the IT unit, which enhances firm performance. Likewise, Schlosser et al. (2015) show that formal and informal integration mechanisms between business and IT improve social alignment, which in turn increases firm performance.

Moreover, close links between business and IT managers are important, as the deployment of IT in value chain activities and its strategic role is impacted by the CIO's involvement in top management team activities. For example, Li and Ye (1999) discover that IT investments have a more pronounced impact on financial performance, when there are closer ties between CEO and CIO. Karahanna and Preston (2013) show that trust between CIO and top management team leads to a closer alignment between IT and business strategy and, consequently, to an improved firm performance.

5.8 External relations

External relations refer to a firm’s relationship with external partners and its reputation or brand (Ray et al. 2013). We identified 29 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with external relations.

Close cooperation with external partners is inherently risky for a focal firm, as potentially sensitive information is shared, rendering a firm susceptible to opportunistic and exploitative behavior (Miao et al. 2018). Accordingly, Powell and Dent-Micallef (1997, p. 382) state that “EDI systems combine intra- and inter-organizational information processing to facilitate sophisticated electronic interactions with suppliers. However, in the absence of open and trusting supplier relationships, such systems can do little but magnify existing suspicions […].” Thus, IT-based integration of external partners is only valuable, if there is a close enough involvement (Zhang and Yang 2016) and trust (Miao et al. 2018) between parties to share accurate and adequate information in a timely manner. For instance, Zhang et al. (2016) show that intra-organizational ICT in combination with information sharing and a cooperative relationship with buyers improves supplier performance.

Besides, IT-based information exchange can help companies to combine their resources and capabilities to seize given business opportunities (Jiang and Zhao 2014). Therefore, the value created by the integration of IT for connecting inter-firm processes depends largely on joint activities between organizations and common understanding how to leverage available resources. Rai et al. (2012) state that inter-firm IT capability enhance relational value co-creation when complemented by exchange of knowledge and ideas among senior (IT) executives. Furthermore, Liu et al. (2016) conclude that it is crucial for companies to align their IT competence with the scope of cooperation and resource sharing among its distribution partners.

A neglected facet is the synergy of firm reputation or brand with IT. Every firm has some form of brand, which promises customers` specific benefits and raises certain expectations. Thereby, some brand orientations may be more synergistic with IT than others. Piccoli and Lui (2014) demonstrate that brand moderates the interaction between the effective use of an IT-enabled service channel and competitive performance in the hospitality sector. Specifically, one brand exhibits a direct positive impact of the IT-enabled service channel on the firm's ability to exceed the revenue per available room of its rivals, whereas the other brand fails in doing so, even though both use the same standardized IT application.

5.9 Worker skill

Worker skill reflects the qualifications and competence of employees that is not directly related or limited to technical abilities. We identified 15 studies that analyze the performance impact of IT in combination with worker skill. Thereby, measures for worker skill are mostly educational level (e.g. Giuri et al. 2008), but also the proportion of unskilled manual workers (e.g. Caroli and van Reenen 2001) or worker compensation (Saldanha et al. 2022). Rarely, a direct measure of worker skill (e.g. Aral and Weill 2007) or the fit between worker skill and job tasks (e.g. Ghasemaghaei et al. 2017) are employed.

IT is considered superior to humans in performing most cognitive and manual routine tasks. For this reason, computers are used for routine operations such as putting pieces together at the assembly line or doing bookkeeping. In turn, the number of cognitive, non-routine tasks at the workplace increases, as computers have difficulties in identifying creative solutions to previously unknown problems, necessitating analytical and cognitive skills (Giuri et al. 2008). Thereby, particularly highly skilled workers seem to benefit from this shift in work tasks, as those have an easier time performing cognitive demanding tasks (Bresnahan et al. 2002).

Yet, research on the complementarity between IT and worker skill is rather mixed. On the one hand, studies suggest a complementary relationship between IT and skilled labor (Bresnahan et al. 2002; Brynjolfsson et al. 2021; Giuri et al. 2008; Moshiri and Simpson 2011; Mouelhi 2009). On the other hand, studies find no significant positive interaction effects between IT and worker skill on organizational performance measures (Arvanitis et al. 2016; Bloom et al. 2012; Caroli and van Reenen 2001) or only in certain settings (Arvanitis 2005; Arvanitis and Loukis 2009). Thus, it appears that the presence of skilled workers does not necessarily enhance the value created by IT resources.

6 Discussion: shortcomings and directions for future research

The concept of resource complementary has been widely applied in ITBV research, yet it seems that so far research has primarily contemplated different pieces of the puzzle, although only by combining them it is possible to obtain a holistic picture and generate more profound insights. Accordingly, our review does not find evidence of a specific pair of IT and non-IT resources, whose relationship is always complementary, irrespective of the institutional or environmental context. Rather, it became apparent that research findings within a resource category diverged in several instances, at times even contradicting each other. For example, some studies identify a decentralized decision structure as a key complement to IT (e.g. Bresnahan et al. 2002; Brynjolfsson et al. 2002), while others find no significant effect (e.g. Arvanitis 2005; Bertschek and Kaiser 2004), and yet others even observe a negative association (Giuri et al. 2008). As an explanation for these ambiguous findings, we have identified five shortcomings in the current literature by systematically examining applied methodologies to detect complementarities, measurement of dependent and independent variables, consideration of environmental factors, and the underlying data sets.

6.1 Current shortcomings in ITBV research and potential resolutions

6.1.1 Shortcoming1: utilizing reductionist approaches

We found that the vast majority of studies focuses on pairwise associations between IT and a single complementary non-IT resource (e.g. Chari et al. 2008; Jeffers et al. 2008). While the analysis of pairwise interactions is a valid approach, as it provides a high level of granularity (Drazin and van de Ven 1985), such a reductionist perspective has its drawbacks.

The process of creating ITBV is multifaceted as demonstrated by the wide range of complementary non-IT resources that have been explored in empirical studies. Thus, one can argue that there is not necessarily a single non-IT resource critical to the successful deployment of IT, but a full system of complementary non-IT resources needs to be in place. Therefore, the sole assessment of pairwise associations seems to be incomplete, as it lacks sufficient capacity to capture multivariate interaction between IT and several non-IT resources (Fink and Sukenik 2011). For instance, firm performance is affected differently when IT and organizational structure are mutually reinforcing, but there is a simultaneous lack of adequately skilled workers or a counteractive culture. In such cases, the analysis of two-way interactions leads to misleading insights, because it assumes that the whole system is decomposable into pairwise associations which can be examined independently, and the acquired knowledge can be re-aggregated to understand the system as a whole (Cao et al. 2011; Drazin and van de Ven 1985). By definition, however, complementarity means that the whole is more than the sum of its parts (Milgrom and Roberts 1990, 1995). Likewise, a system may fail, if only one single piece is missing, making any piecemeal view potentially deceptive (Nevo and Wade 2010; Someh et al. 2019). Therefore, the absence of complementary relationships between IT and a single non-IT resource cannot disregard the possibility of synergies, as the two resources may only become complementary when a third resource (or a set of resources) is added (Ennen and Richter 2010). Thus, complementarity effects may only emerge when a resource is embedded in an overall system that includes many elements.

Yet, most of the empirical studies in our review follow a bivariate fit or a two-way interaction approach (see Online Appendix A). While some consider several complementary non-IT resources, they mostly analyze a multitude of separate pairwise interactions instead of taking a system approach (e.g. Albadvi et al. 2007). At least some studies extend this perspective by utilizing three-way-interactions between different resources to examine a larger set of complementarities (e.g. Tambe et al. 2012). Only a few studies apply a system approach by utilizing deviations from ideal profiles (e.g. Bergeron et al. 2001; Fink and Sukenik 2011; Liu et al. 2016), covariation analysisFootnote 3 (e.g. Chen 2012; Gu and Jung 2013), cluster analysis (e.g. Bergeron et al. 2001, 2004; Buttermann et al. 2008; Pollalis 2003), or, more recently, fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis (Park et al. 2017, 2020; Park and Mithas 2020). Nevertheless, even these studies still mostly encompass a small set of different heterogenous resources like IT, strategy, and structure (Bergeron et al. 2001, 2004) or IT, strategy, and processes (Pollalis 2003), limiting our knowledge on larger sets of synergistic resource configurations.

In sum, we argue that research regarding complementary non-IT resources has to progress beyond a reductionist view, since there is still a major knowledge gap regarding different configurational recipes of IT and complementary non-IT resources that are necessary or sufficient to achieve a desired performance outcome. To address this issue, studies can apply currently underutilized approaches such as ideal profile deviation, cluster analysis, or fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis.

6.1.2 Shortcoming 2: employing monolithic IT resource measures

A variety of studies tries to identify complementarities between IT and non-IT resources by utilizing monolithic IT measures (e.g., Bertschek and Kaiser 2004; Bresnahan et al. 2002). However, such an approach may result in an incomplete understanding and interpretation of the complementary nature of IT.

Firms are pursuing diverging strategies, resulting in different IT investments and varying IT resources between firms (Aral and Weill 2007; Tallon et al. 2000). Under this assertion, utilizing a single, composite IT measure implies that the different types of IT such as ERP systems, data networks, electronic messaging systems, or computer-aided design (CAD) systems can be seen as a homogenous resource bundle. Given their different functions, areas of application, and strategic purposes this seems, however, rather doubtful. In that sense, a failure to disentangle IT is tantamount to assuming that either all firms have an equal bundle of IT resources or that there is no difference between the varying types of IT a firm possesses with respect to their interactions with complementary non-IT resources. Unfortunately, both of these assumptions are clearly flawed.

Accordingly, empirical research has shown that investment in different types of IT may even require competing non-IT resource complements (Steelman et al. 2019; Stucki and Wochner 2019). Bloom et al. (2014) show that communication enhancing IT (e.g. intranets, e-mail) tend to reduce communication costs, which foster a centralized structure, as decisions will be passed up to the managers of the firm. In contrast, advanced IT (e.g. ERP systems, CAD systems) provide workers with the ability to solve a wide range of tasks on their own and lowers the information acquisition costs, facilitating a decentralized structure. Building on these insights, Stucki and Wochner (2019) indicate that greater employee voice promotes firm productivity when combined with advanced IT, but suppresses firm productivity when combined with intranets (et vice versa).

Consequently, we propose that studies need to take a more nuanced perspective on IT resources and make a distinction between different types of IT when examining its complementarity with non-IT resources. Thereby, promising avenues to disentangle IT seem to be either along functional dimensions (Stucki and Wochner 2019) or its strategic purpose (Aral and Weill 2007) to generate more detailed insights. Of course, this also applies to the measure of the non-IT resource, as it is essential to conceptualize each resource onto the same level of analysis before assessing resource complementarity.

6.1.3 Shortcoming 3: neglecting environmental uncertainty

We have already argued that the diverse subsystems of an organization should fit together to create business value from IT. There should, however, not only be a coherence between them, but also compatibility with environmental factors (Melville et al. 2004). These factors can be seen as a reflection of the uncertainty in the operating environment of an organization (Wade and Hulland 2004). Thereby, three distinct dimensions commonly characterize environmental uncertainty: heterogeneity, dynamism, and hostility (Miller and Friesen 1983). Heterogeneity refers to the diversity of an industry or organizational activities. Dynamism describes the rate of change in the environment. Hostility pertains to the intensity of competition (Miller and Friesen 1983). These environmental factors have the potential to suppress or reinforce the positive effect of complementarity between IT and non-IT resources on organizational performance (Yayla and Hu 2012). Surprisingly, only 17 out of the 227 studies investigate how different environmental conditions interact with a certain set of IT and non-IT resources to affect organizational performance (e.g. Choe 2003; Li and Ye 1999; Sabherwal et al. 2019; Yayla and Hu 2012). Thereby, scholars generally argue that business-IT misalignment is severely punished in a highly uncertain environment, as companies cannot afford dysfunction if they want to survive in such conditions, while misalignment has only minor consequences in a stable environment, as there may, for example, be not enough competitors to capitalize on it. Accordingly, Yayla and Hu (2012) show that a positive effect of strategic IT alignment on performance is present in relatively stable conditions, but becomes distinctly more pronounced in volatile ones.

However, an aggregated investigation of alignment between resources is potentially misleading, as it implies that there is no distinction between different resource combinations, as long as they are aligned. Yet, the effect of resource complementarity on firm performance may not only depend on the fit between IT and non-IT resources, but also on the fit of a given resource system with the corporate environment (Andersen 2001; Li and Ye 1999). For example, a resource system designed around communication-enhancing IT with a centralized structure and low skilled workers may be suited to a homogenous environment with low information needs, rather than heterogeneous environments where information needs are high and information overload for managers is eminent. For a resource system designed around advanced IT with a decentralized structure and high-skilled workers, the opposite might be true, although the resource system is internally consistent in either case. Therefore, the value created by resource interactions may be sensitive to external contingencies, making “the same resources valuable in some contexts and not in others” (Brush and Artz 1999, p. 223). Consequently, studies should consider how environmental conditions affect the performance impact of different combinations of IT and complementary non-IT resources, as certain resource systems may only create business value in specific environments.

6.1.4 Shortcoming 4: taking a cross-sectional perspective

Furthermore, our review reveals that empirical studies on resource complementarities in ITBV research take mostly a cross-sectional perspective (see Online Appendix A). However, studies need to account for lag effects that might occur between attempted resource complementarity and actual performance enhancing effects. This is problematic, as the creation of a synergistic resource system does not only depend on the acquisition of such resources but also the ability of a firm to combine them adequately, leading to a delay between investment in complementary non-IT resources and eventual emergence of resource complementarity. In addition, even if resource complementarity is realized, it still may take time until performance effects become measurable at the firm level.

Moreover, while some studies have longitudinal data for IT and/or performance measures, enabling them to address lag-effects, they often lack such for complementary non-IT resources. Therefore, they rely on the assumption of complementary non-IT resources being quasi-fixed in the short term (e.g. Aral et al. 2012; Bloom et al. 2012; Bresnahan et al. 2002). In practice, the resource base of a firm is, however, in a constant state of flux (Tallon et al. 2016). That is why the assumption of quasi-fixed complementary non-IT resources may lead to deceptive conclusions. Adding to that, the lack of longitudinal research has also led to a limited understanding on the sustainability of a competitive advantage based on complementarity between IT and non-IT resources, as well as elusive insights on how firms transition between different combinations of IT and non-IT resources over time. Future research should address these shortcomings by utilizing longitudinal datasets.

6.1.5 Shortcoming 5: use of broad and aggregated performance measures

Finally, studies often apply broad performance measures such as productivity (e.g. Stucki and Wochner 2019), return on assets (e.g. Shin 2001), or market value (e.g. Brynjolfsson et al. 2002) to assess the impact of a combined deployment of IT and complementary non-IT resources. Such an approach makes it difficult to identify a meaningful relationship between resource complementarity and organizational performance due to an extensive sequence of intermediate activities as well as a large temporal gap between resource deployment and firm level impact.

In addition, Aral and Weill (2007, p. 763) argue that “[f]irms’ total IT investment is not associated with performance, but investments in specific IT assets explain performance differences along dimensions consistent with their strategic purpose." Hence, different types of IT resources have distinct effects on firm performance (Aral and Weill 2007; Weill 1992). Consequently, specific combinations of IT and complementary non-IT resources may only affect specific performance dimensions. For example, certain combinations of IT and non-IT resources may be more prone to result in super-additive IT value synergies, while others may result in sub-additive IT cost synergies (Schryen 2013).

Thus, empirical studies should apply a more fine-grained depiction of the value creation process by including intermediate performance outcomes. For one, studies could incorporate more granular performance indicators that are closely linked to specific activities within an organization (Schryen 2013). Another interesting approach could be to explain the value creation from IT along the dimensions of IT-enabled organizational capabilities that emerge from the interplay between IT and complementary non-IT resources (Oh and Pinsonneault 2007; Tanriverdi 2005). For instance, Trainor et al. (2014) show that the synergistic interaction of a customer-centric management system with social media technology use enables social customer relationship management capabilities that subsequently enhance customer relationship performance, painting a detailed picture of the business value created from social media technology use. Hence, future research should progress beyond the sole assessment of broad and aggregated performance measures by either including fine-grained intermediate performance indicators or incorporating IT-enabled organizational capabilities to shed more light in the process of ITBV creation.

Additionally, studies currently predominantly consider super-additive IT value synergies, often neglecting sub-additive cost synergies. In a similar vein, studies could also include alternative performance measures to the prevalent financial ones, such environmental or social performance (for an example see Yang et al. 2018).

6.2 Summary of recommendations for future research based on the identified shortcomings

The previous section highlighted paths to address shortcomings in the current literature and thus entails avenues for future research efforts, which are summarized in Table 4.

6.3 Future research opportunities related to specific resource categories

While we are confident that the identified shortcomings cover the most pressing issues in research on complementarity in the ITBV domain, we recognize that the study of pairwise relationships (i.e. the interaction between IT resources and a specific resource category like strategy) remains an important line of inquiry due to the high degree of granularity such an approach offers. Accordingly, we see further research opportunities regarding specific resource categories as well:

-

(1)

Although the research efforts on strategic IT alignment have been extensive, one aspect that has received scarce attention is the alignment of IT and business strategy at business function level. While there are some studies that address the alignment of IT and marketing strategy (Al-Surmi et al. 2020; Hooper et al. 2010) as well as IT and supply chain strategy (Qrunfleh and Tarafdar 2014; Wei et al. 2022), we believe that further research in this area is warranted. Particularly, since the IT function takes on a central role within most organizations and often supports the strategy implementation of other business functions. This makes an aligned strategy necessary to ensure an effective use of resources and to achieve overarching business goals. Likewise, there is still a lack of research on strategic IT alignment at the business unit level and its interaction with corporate business strategy (Queiroz et al. 2020).

-

(2)

A variety of research papers have focused on the interaction between decision structure and IT resources. Yet, other relevant aspects of organizational structure such as formalization, specialization, functional differentiation, or professionalization have so far received far less research attention. Therefore, we urge further investigations of these sub-categories to broaden our understanding of the interplay between structure and IT.

-

(3)

Given the increasing importance of green initiatives, the literature has so far remained surprisingly silent on the business value impact of achieving fit between IT and a green culture (Yang et al. 2017), creating congruence between IT and green practices (Ryoo and Koo 2013), or establishing alignment between IT and a green business strategy (Forés 2019; Yang et al. 2018). Given that a variety of stakeholders increasingly demand that firms operate in a sustainable manner, organizations may be able to gain a competitive edge by establishing an environmental-friendly image. Thus, we encourage future research efforts to explore the business value creation from aligning IT with green initiatives.

-

(4)

Our review revealed that culture is mostly assessed by evaluating the degree to which an organization fosters open communication (e.g. Jeffers et al. 2008). While this is an important aspect, there may also be other relevant facets of culture that are critical to the successful deployment of IT such as commitment towards innovation (Bradley et al. 2006). Hence, future research could examine other facets of culture. Moreover, it seems likely that employee behavior is shaped by the interplay between the different cultural levels (i.e. organizational and national) (Leidner and Kayworth 2006). Future empirical studies could thus attempt to address this issue by examining the interplay between IT and organizational as well as national culture. In this sense, comparing the interaction between IT and organizational culture in different countries may also offer interesting insights.

-

(5)

Another neglected facet is the complementary relationship of firm reputation or brand with IT (Piccoli and Lui 2014). Since customers tend to associate different firms or, more specifically, their brands with different value propositions or standards, it may well be that IT investments work better for some firms because customers are more likely to perceive IT initiatives as "fitting" with the brand image. Hence, further research could add to the currently small body of literature on the synergies of IT initiatives and brand image.

-

(6)

Finally, our review revealed that there is a distinct lack of empirical studies that examine the synergies emerging from the interaction between IT and worker skill. For example, studies have so far predominantly investigated the interaction effect of IT and worker skill on productivity, with little research considering other performance measures.

7 Conclusion

In light of the continuing ambiguity about the performance effects of IT resources, the aim of this review is to provide a holistic perspective on ITBV. Thereby, we extend existing conceptual works (Kohli and Grover 2008; Melville et al. 2004; Wade and Hulland 2004; Wiengarten et al. 2013) by providing a converging definition and comprehensive classification of complementary non-IT resources to unite the dispersed and insulated literature. Based on these insights and a thorough examination of the prevalent theoretical lenses (i.e. microeconomic theory, RBV, and contingency theory), we also present an integrative framework on resource complementarity in ITBV research. Moreover, we identify five shortcomings in the extant literature, which are the (1) predominant use of reductionist approaches, (2) reliance on monolithic IT measures, (3) disregard of environmental uncertainty, (4) widespread use of cross-sectional data, and (5) utilization of broad and aggregated performance measures. In doing so, we demonstrate the eminent need for more depth and breadth in research on resource complementarity as well as offer a broad range of opportunities for future research.