Abstract

Although episodic volunteering is a popular form of volunteering and has received increasing attention from researchers, the motives and characteristics of episodic volunteers in different industries or types of events remain underresearched, especially in the context of cultural events. This study is based on a sample of more than 2000 episodic volunteers and analyzes demographic characteristics, motives, and volunteer experience of cultural event volunteers by applying between and within analysis. The between analysis compares cultural and social event volunteers and finds that cultural event volunteers show higher time engagement but are more self-serving in their motives. The within analysis emphasizes intrinsic motives over extrinsic motives, leading to the conclusion that saturation of extrinsic motives reduces willingness for future engagements.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Nonprofit organizations (NPOs) rely on volunteers as an important resource to provide services. By doing so, they can reduce salary expenses, expand their programs and services, and establish a connection to the local community (Snyder & Omoto, 2008). Consequently, many organizations depend on volunteers, but many also experience decreasing numbers of volunteers (Gage & Thapa, 2012). In Switzerland, for example, formal volunteering has been declining over the last decade (Freitag et al., 2016).

However, this declining trend does not hold for all areas and types of volunteering. The social sector, for example, has a long tradition of long-term volunteering at all organizational levels. The ongoing transition from traditional collectivistic volunteering to new individualistic volunteering creates shortfalls in this industry (Hustinx et al., 2016). Health and social welfare organizations also benefit from increasing government funding (Katz et al., 2018), which makes it easier to attract and retain paid staff and reduces the need for volunteers. In fact, volunteers are often viewed as unprofessional because they receive limited task-specific training, have little if any disciplinary knowledge, and, although their work has significant social consequences, have only limited decision-making power (Ganesh & McAllum, 2012). Other sectors, such as the cultural sector, have witnessed declining streams of government funding and donations, forcing them to rely more heavily on volunteers. For them, attracting greater numbers of volunteers has become crucial to fulfilling their mission. For instance, in the cultural sector, volunteers are becoming a more attractive resource that is often overlooked in research, especially in museums and other institutions (Dickson, 2018).

Despite industry differences, episodic volunteering or microvolunteering is increasing in all areas, echoing changes in lifestyle and time consumption (Heley et al., 2019). In a society characterized by increasing time constraints and less commitment to long-term engagements, episodic volunteering is convenient since it requires less commitment from potential volunteers (Hyde et al., 2016). Cnaan et al. (2021), in their literature review of episodic volunteering, define episodic volunteering as “(…) a one-time (usually a few hours) assignment to perform a non-complicated that does not require elaborate training, or alternatively, a very specialized and specific task, such as in pro bono volunteering utilizing skills already possessed by the volunteer (…).” (p. 4). This definition is used throughout this study.

In recent years, scholarly interest in volunteering has shifted away from long-term engagement toward more temporary forms of volunteering (Güntert et al., 2015). These forms include informal, short-term, or event-based volunteering (Handy et al., 2006). A growing body of literature addresses episodic volunteering, but studies often generalize results across different types of episodic volunteers (EVs) rather than distinguishing specific groups of volunteers (Cnaan et al., 2021). However, episodic volunteering at cultural events has received limited scholarly attention (Lockstone-Binney et al., 2010). Reviews of empirical evidence concerning the motives for episodic volunteering typically focus on sports, tourism, health, and social welfare; findings are often (over)generalized, but arts and culture are rarely considered as a separate category (Cnaan et al., 2021; Güntert et al., 2015).

Additionally, researchers have pointed out that the motives of EVs at events might differ from those of “regular” or ongoing volunteers (Bang et al., 2009), as the frequency and intensity of their efforts are less than those of regular volunteers (Hustinx et al., 2008). In general, volunteering is usually considered an apparent manifestation of altruistic or prosocial behavior, but some researchers argue that volunteering has a transactional or “rational” character in which individuals give and receive something (Lee & Brudney, 2009). However, little research has examined differences among EVs in various sectors (Dunn et al., 2016). EVs may differ in terms of their altruistic motivations in traditional volunteering contexts (Güntert et al., 2015). Analyzing the different determinants of volunteering across industries or types of events or the organizational and institutional context of volunteering would be helpful to understand the motives and drivers of episodic volunteering and improve the management of EVs (Handy et al., 2006).

This study, as part of a special issue on episodic volunteering, aims to add to a better understanding of the two aforementioned aspects. Our study analyzes EVs in the art and cultural area (henceforth referred to as cultural EVs) and compares them to those volunteering in health and social welfare (henceforth referred to as social EVs). Assuming that EVs select events based on their personal goals, preferences, and motives and that time devoted to volunteering is constrained, in this study, we ask two questions:

-

RQ1: What is the unique demographic background of individuals who volunteer at cultural events compared to volunteers at social events, and what are their primary motivations?

-

RQ2: What motives of EVs at cultural events influence their willingness for future engagements?

The present study is exploratory and intended to yield a better understanding of EVs in the cultural sector. We assess the motivations and experiences of EVs within and between this sector and the social sector. Additionally, we assume that volunteering experience shapes individuals’ decisions to volunteer again. In this regard, we explore whether cultural EVs are more self-serving than other-serving compared to volunteers at social events, thereby providing evidence for the transactional character of volunteering. The article is structured as follows: First, we provide an overview of the literature on volunteering concerning sociodemographic characteristics, intrinsic and extrinsic motives, and volunteer experience. Then, we provide information on the data collection and the applied methods. The results are presented, followed by discussion. Finally, we highlight implications for research and practice in the conclusion.

Literature Review

Sociodemographic Characteristics of Volunteers

Researchers generally agree that people with higher economic and social status tend to volunteer more, as highlighted in a literature review by Wilson (2000). The relationship between income and volunteering is somewhat counterintuitive to the theory of rational choice, which assumes that volunteer hours are inversely related to wages due to higher opportunity costs (Wolff et al., 1993), although other researchers use rational choice theory to explain why volunteering takes place more often among resource-rich individuals than resource-poor individuals (Musick & Wilson, 2008). They argue that people who are better off financially or have more knowledge and skills find it easier to volunteer and are more likely to benefit from volunteering. Education is considered to be one of the most important predictors of volunteering (Son & Wilson, 2012), which is generally explained by a higher awareness of societal problems, more requested skills, and a larger social network (Ariza-Montes et al., 2015).

The research is inconclusive about two other sociodemographic factors: religious affiliation and gender. Religion can be a driver of volunteering, but only when measured by church attendance or embeddedness in a church context and not simply by church membership (Ruiter & De Graaf, 2006). The influence of religion increases if it is connected to a stronger sense of community attachment (Grønbjerg & Never, 2004) or is tied to a set of values that encourage voluntary engagement (Stukas et al., 2016). Evangelical protestants and Catholics are less likely to volunteer than liberal protestants (Musick & Wilson, 2008). With respect to gender, research across different countries has yielded divergent results regarding the likelihood and extent of volunteering by women and men (Wilson, 2000). Einolf (2011) shows that the contradiction between the general expectations that women show higher interest in helping others and low gender differences in institutional volunteering can be partially explained by men’s better resource access and secular networks, while women are stronger in church volunteering. More recent studies have confirmed that women volunteer more in church but have found no differences in secular settings (Krause & Rainville, 2018).

Finally, age influences the decision to volunteer and the rate of volunteering, primarily because motives and sociodemographic factors change across different stages of life (e.g., income). As age increases, career-enhancing and learning motives become less important, and social motives increase (Okun & Schultz, 2003). Middle age represents the peak of the volunteering commitment, whereas individuals in their early twenties are least likely to volunteer (Son & Wilson, 2012). In an Australian sample, Gray et al. (2012) find that younger adults are more likely to volunteer in religious organizations, middle-aged adults in sports and education organizations, and old-aged adults in social and welfare organizations.

Assessing sociodemographic characteristics in relation to EVs’ motives, Dunn et al. (2016) note in their literature review that most studies on episodic volunteering do not ask for demographic information, and it therefore is not possible to draw any conclusions. Hence, our investigation of the differences in sociodemographic characteristics of cultural and social EVs is an important contribution to a better understanding of episodic volunteering.

Intrinsic and Extrinsic Motives for Volunteering

The different motives behind the decision to volunteer can be roughly divided into two main groups of motivational orientations, intrinsic and extrinsic motives (Finkelstein, 2009; Meier & Stutzer, 2008) or, similarly, altruistic and utilitarian motives (Handy et al., 2010). However, a variety of motives are nearly always responsible for the decision to volunteer, and they are often interconnected (Holdsworth, 2010; Kühnlein & Böhle, 2002).

The first group of motives can be considered intrinsic or altruistic: people volunteer because they find it inherently interesting or satisfying and, therefore, benefit from caring for others’ welfare (Meier & Stutzer, 2008) and not because they receive an apparent reward from volunteering (Deci, 1971). When volunteering is an intrinsically motivated activity, psychologists consider it a form of self-expression (Amabile, 1993). Andreoni (1990) terms this enjoyment from the well-being of others “warm glow” (1990). Hence, people will engage out of personal interest or compassion without always reasoning about any countervalue. Hackl et al. (2010) model this intrinsic behavior in their consumption hypothesis, where volunteering is treated as an ordinary consumption good to increase one’s utility. According to this hypothesis, individuals volunteer either because they enjoy the activity itself (e.g., walking shelter dogs) or because they enjoy the output of that activity (happy dogs). Burani and Palestini (2016) point out that intrinsic motivation is especially relevant in the nonprofit sector, since it is often collective goods and services that are produced, and there is a lack of external incentives for people who are otherwise motivated. From an economist perspective, free-riding is not just a problem in the provision of collective goods; it can also be problematic when people care about beneficiaries’ utility without enjoying the task or social interaction of volunteering per se (Meier & Stutzer, 2008). In this case, it would be enough to see others helping the beneficiaries. Therefore, even for intrinsically motivated volunteers, the work itself must be rewarding beyond the warm glow they receive from observing someone’s well-being improvement.

Economists therefore stress the importance of incentives provided by organizations to activate volunteers (Musick & Wilson, 2008). This concept leads us to the second group of motives, which can be considered instrumental or utilitarian, or the extrinsic motivation to volunteer. Extrinsically motivated volunteering is conducted to obtain a certain outcome or receive some instrumental value or an extrinsic reward (Lee & Brudney, 2009; Ryan & Deci, 2000). An example is a certificate gained by volunteering that can be used on the labor market, which would make volunteering an investment in oneself rather than in others (Hackl et al., 2010). Another example of a utilitarian motive would be to garner prestige or social esteem (Cappellari et al., 2007) or to develop a new skill (Handy et al., 2010).

Motives for volunteering can also be further differentiated than the dichotomous division of intrinsic and extrinsic, such as through the “Volunteer Functions Inventory” (VFI) of Clary et al. (1996), which includes six motives for volunteering (enhancement, values, social, understanding, protective, career). Some researchers consider only one of these motives (values) a truly intrinsic motive (Omoto & Snyder, 1995), whereas others consider only one (career) as purely extrinsic (Finkelstein, 2009). A meta-analysis of studies applying the VFI finds that only 18 of 48 studies confirmed the original factor structure (Chacón et al., 2017), so the application of the VFI does not always lead to conclusive results. Some researchers have adapted the VFI to their research context, e.g., Erasmus and Morey (2016), who have added a motive for faith-based volunteers. Other research supports different categorization of motives, e.g., Cnaan and Goldberg-Glen (1991), who find empirical support for a unidimensional construct that includes both selfish and selfless motives, or Ullah Butt et al. (2017), who have developed a four-factor solution for volunteer motives.

Research on the motives of EVs has increased over the past decade (Dunn et al., 2016). Treuren (2014) clusters different volunteer motives and finds that typical event volunteers have at least two motives present, and only very few (less than 25%) in his sample are motivated by only one reason but do not use an established set of motives, such as the VFI. Hustinx et al. (2008) find that EVs, compared to regular volunteers, are more likely to be motivated by altruistic motives. In their systematic review of EV motives, Dunn et al. (2016) find that enhancement, values, and social motivations of the VFI are preeminent across sectors. Concerning differences among different sectors, Dunn et al. (2016) find that the protective function is specific to charity sport event volunteers only; understanding is represented in all sectors except cultural events; and career is important only for health and social welfare volunteers and sport (noncharity) events. Based on a systematic literature review on episodic volunteering in the health and social welfare sector, Hyde et al. (2014) list the following motives: (1) supporting the cause, helping others or civic duty; (2) psychological or physical enhancement, goal accomplishment; and (3) socializing and enjoyment. Other motives, such as skill development or giving back, are less common. The findings of individual studies are contradictory regarding whether EVs are generally more or less altruistic (Handy et al., 2006; Hustinx et al., 2008), but helping others and enjoying social interactions seem to be the most important motives for EVs (Dunn et al., 2016).

To date, three studies have examined the motives of cultural EVs: Handy et al. (2006) use survey data from EVs at festivals and cultural events in Canada to compare different forms of volunteers within that group, i.e., long-term committed, habitual, and genuine EVs. They find that EVs at cultural events in Canada were more motivated by self-serving than by other-serving motives. Campbell (2009) finds that women volunteering at a folk festival in Australia are motivated by a sense of belonging to a group, being valued as a contributor, enjoying insider benefits, and pride regarding what they have achieved. Hassanli et al. (2020) find that serving as volunteers at a cultural event helps migrants build social capital because they do not feel like “takers” or “free-riders.” One difference between cultural EVs and EVs in other sectors seems to be that EVs at cultural events are not as driven by the extrinsic motive of learning and using skills (Campbell, 2009; Handy et al., 2006).

Volunteering Experience

Social scientists believe that an individual’s actions are determined by past experiences (Mayer, 2004). Some researchers have applied this view to volunteering to better understand drivers and the context of volunteering over an individual’s lifetime (see Hogg (2016) for an overview). According to them, the decision to volunteer depends not only on the motives but also on the quality and context of the volunteer experience. Positive volunteering experiences make volunteers feel appreciated and needed (Starnes & Wymer Jr, 2001). Many organizations are also actively assessing their volunteers’ satisfaction, assuming that happier volunteers are more likely to return (Finkelstein, 2008). Several studies show that high satisfaction with the volunteer experience increases willingness for future engagement (Hyde et al., 2016; Trautwein et al., 2020). Concerning EVs, one could argue that the volunteer experience is less important, as the intention is a one-off experience. This assumption might hold for a single organization or a single event. However, on a more general level, a single volunteer experience exerts an impact on the general willingness to volunteer (Hager & Brudney, 2011). Hence, a bad experience as an episodic volunteer will also affect the person’s willingness to engage in other forms of volunteering.

Additionally, the organizational context influences the volunteer experience (Studer & von Schnurbein, 2013). Volunteers need to be treated as a unique organizational resource, as they differ from paid staff. Thus, volunteer management has to go beyond general human resource activities to encompass volunteers’ interactions and specific expectations (Studer, 2016). Additionally, the conflictual nature of the relationship between paid staff and volunteers influences the volunteer experience (Kreutzer & Jäger, 2011). From the volunteer perspective, interpersonal relationships with other volunteers or paid staff in the organization are an important driver of continued engagement (Rimes et al., 2017). Although EVs are—due to their short activity—less integrated into the organization, their willingness for further engagement depends on their needs being met (Onyx et al., 2007).

Given the exploratory nature of our study, we cannot formulate clear hypotheses. However, based on the existing literature, we expect to find sociodemographic differences between cultural event and social event EVs, especially in terms of major characteristics of volunteering in general, such as age, religion, and education. In regard to motives, previous literature suggests that episodic volunteering at cultural events can be explained by the transactional character of volunteering. In comparison with social event EVs, we expect cultural event EVs to be more self-serving. Finally, we aim to improve our understanding of how the volunteering experience induces EVs’ future engagement. Here, we expect that future engagement is dependent on how EVs’ needs are met.

Data

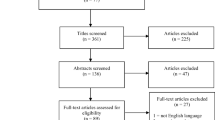

The data for our analysis originate from a sample of EVs at cultural events (n = 1712) and at social events (n = 732) from 15 countries (Australia, Bahrain, China, Colombia, India, Israel, Japan, Kuwait, Mexico, Russia, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Switzerland, Tanzania, the United States). Cultural events included music festivals, concert series, renaissance fairs, and art exhibitions. Social events covered a wide range of events aimed at helping socially disadvantaged people, for example, a Red Cross annual hunger day, a flood relief camp, or fundraising events for charities helping the poor.

The data were collected in 2017 and 2018 through online surveys and personal interviews as part of an international research project on episodic volunteering. The questionnaire used in the research project was originally developed by a team of international researchers; it was based on Cnaan et al. (2017) and was later assessed by a panel of experts from both academia and professional practice to verify face validity and adapt it to different country contexts, if necessary. The instrument included up to 100 survey items,Footnote 1 asking about the respondents’ demographic characteristics, details about their volunteer assignment, and several questions concerning their motives and satisfaction with their event volunteering experience.

Table 1 in Appendix provides an overview of the number of individuals from each country and group (social and cultural) used in this analysis.

Methodology

For the between-group analysis, the sample was categorized by a dummy variable coded 1 if the EV was volunteering at a cultural event (group CULTURAL) and 0 if she or he volunteered at a social event (group SOCIAL). The relevant survey items were then analyzed with Welch’s test for unequal variances and Pearson’s Chi-square test. Differences in answers within each group were also tested for and were statistically significant at a cutoff value of p < 0.1.

When sample sizes and variances are unequal, Student’s t-test is quite unreliable, and Welch’s test for unequal variances tends to perform better (Ruxton, 2006). Consequently, we used Welch’s test to analyze the data that were measured in rankable categories (e.g., monthly gross income). The test statistic for the unequal variance t-test (t’) is:

For categorical, nonrankable data, we used Pearson’s Chi-square test, and for those items assessed in a 2 × 2 contingency table, we likewise used Pearson’s Chi-squared test with Yates’ continuity correction to account for the upward bias (Yates, 1984). This correction is formulated as follows, with \(f_{o}\) and \(f_{e}\) being the observed and expected frequencies, respectively:

We used logistic regression to conduct within-group analysis of the cultural volunteers for the dependent variable “consideration of returning as an EV.” Logistic regression can be used to estimate the relationship between a binary dependent variable and a set of metric or nonmetric independent variables. Although similar to discriminant analysis, it offers the advantage of being unaffected by possibly unmet assumptions and is similar to a multiple regression (Hair et al., 2014).

Variables

Sociodemographic Characteristics

To analyze sociodemographic differences between the two groups, we looked at their income, age, gender, marital status, and the importance of religion. Table 2 in Appendix presents the variables, scales, and analysis of differences.

Motives for Volunteering

Following researchers such as Finkelstein (2009), we employ an intrinsic/extrinsic distinction of motives. Intrinsic motives were defined as motives related to “the doing of an activity for its inherent satisfactions rather than for some separable consequence” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 56). Six survey items were, according to this definition, categorized as intrinsic motives.

Extrinsic motives were defined as those that relate to “an activity [that] is done in order to attain some separable outcome” (Ryan & Deci, 2000, p. 60). Six survey items were accordingly categorized as extrinsic motives. Table 3 presents the categorized items, scales, and the analysis of differences.

Experience and Preference for Volunteering

The experience with episodic volunteering was measured by asking about the number of hours volunteered, the overall perception of the volunteer experience, and the preference for episodic volunteering over regular volunteering. We therefore examined previous and present (event-day) experiences. Although the “volunteer experience” is a complex product of satisfaction, motives, and the fulfillment of expectations (Haski-Leventhal & Meijs, 2011), we focused on organizational and contextual factors to complement the analysis of EV motives.

Intentions to Return

Finally, we asked cultural EVs about their intentions to volunteer for a similar one-time event in the future. This question was not included in the surveys conducted in Colombia, Mexico, and Russia.

Results

Between-group analysis

Tables 2, 3, and 4 show the differences between volunteers at cultural and social events with regard to sociodemographic characteristics, motives, and overall volunteer experience, respectively.

Table 2 shows that cultural EVs are significantly younger, less religious, and have lower income on average than social EVs. The findings demonstrate statistically significant relationships between volunteers’ gender and marital status and the grouping variable: Males are more likely to volunteer at cultural events than at social events, and unmarried people are more likely to volunteer at cultural events than at social events.

Table 3 analyzes differences in motives between the two groups, utilizing the dichotomous categorization of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation. The results show some statistically significant differences in motives between volunteers at cultural events versus social events. Regarding intrinsic motives, cultural EVs rated pride in being part of the community, satisfaction of working with other people, and looking for a fun and challenging activity more highly than did social EVs. Social EVs appear to be more motivated by setting an example for others (intrinsic) and fulfilling civic duties (extrinsic). Extrinsic motivation seems to play an important role for cultural EVs, as they are significantly more motivated by fulfilling school requirements, meeting new people, or friends asking them to volunteer.

Table 4 addresses the differences in the quality and preferences of volunteer assignments. Cultural EVs volunteer slightly more hours, but social EVs rate their experience more highly than cultural EVs. A majority of both groups preferred episodic volunteering to regular volunteering.

Within-Group Analysis of Cultural EVs

Using logistic regression, we analyzed which factors contribute to the returnability of cultural volunteers. The model predicts the likelihood that a cultural volunteer will consider volunteering for other similar one-time events. Questions regarding the motives for volunteering were used as independent/predictive factors. Age, income, overall event experience, previous regular volunteering experience, and previous episodic volunteering were included as control variables, as we expect them also to influence the decision to engage in further episodic volunteering. As mentioned in the variable section of this paper, the question regarding the intention to return as an EV at a similar one-time event was not included in Russia (518 cultural EVs), Colombia (17), and Mexico (9), which is why the sample, after listwise deletion of cases from other countries, resulted in a sample size of n = 646 EVs in the cultural sector. Table 5 in Appendix presents the results of the logistic regression.

The Nagelkerkes R2 for the model was 0.387, and the Chi-square test for overall model fit achieved statistical significance (p < 0.01). The average variance inflation factor (VIF) is 1.62, which indicates that multicollinearity is not an issue. The significance of the regression coefficients was assessed through a Wald test. To ensure easier interpretation of the model, the odds ratios are included in Table 5. They represent the constant effect of a predicting variable on the likelihood that a given outcome will occur; in this case, the outcome is answering “yes” to the question of returning to volunteer at a similar one-time event. The results show that previous regular volunteering experience increases the chances of returning as an EV. However, having previously engaged in episodic volunteering does not seem to affect the chances of returning to it. Volunteering to have fun and because someone seeks emotional satisfaction or takes pride in being part of a community significantly increases the likelihood that someone will engage again in episodic volunteering. When respondents volunteered to meet new people or because they were able to use their skills, the chances of returning as an EV decreased. The strongest significant and positive effect can be seen in the control variable quality of event volunteering experience.

Discussion

Our study aimed to better comprehend the motives of EVs at cultural events. We chose a within-/between-group approach in which we first compared EVs in the cultural and social sectors and then analyzed the motivations of EVs within the cultural sector with respect to their willingness to engage in future episodic volunteering. In addition to sports, the social sector is one of the most prominent fields for episodic volunteering, whereas volunteers in the cultural sector have attracted comparatively less attention. Our results offer new insights into the motivations of cultural EVs.

First, people who volunteer in the cultural and social sectors differ according to their sociodemographic characteristics. Our study shows that volunteers in the social sector tend to be older, have higher income, be more likely to be married, and be more religious. In both social and cultural areas, more women than men volunteer in the events we studied, and men are more likely to engage in cultural events. In particular, as some of the events in this study were music festivals, the technical aspect and the general characteristics of the events might be more appealing to men. Additionally, EVs at cultural events are significantly younger.

In regard to episodic volunteering activities and experiences, the findings show that EVs at cultural events invest more time and feel more appreciated. One reason might be that cultural EVs are closer to the overall target group of cultural events. Although they prefer episodic volunteering over traditional volunteering, they are less frequently engaged, both in the past and in their future volunteering plans. Volunteer experience is less relevant for cultural EVs, and thus, organizers should have fewer expectations to count on previous experiences. Additionally, EVs at social events show a higher connection to the general cause, as they are more likely to make a donation in addition to their time engagement. A possible explanation for this difference is that EVs at cultural events often see their engagement as substitution for paying an entrance fee. Thus, making a donation would conflict with this initial motivation.

In terms of motivational aspects, we differentiated between intrinsic and extrinsic motives. Generally, we do not find a preference for either intrinsic or extrinsic motivation in either EV group or any specific dominant motivational aspect. This finding is consistent with previous research on the variety of motivations for volunteering (Holdsworth, 2010). When comparing cultural and social EVs, we thus find differences in the motivations of the two groups. Compared to cultural EVs, helping others is more relevant for social EVs (fulfilling civic duties, setting an example for others). While the two groups show no difference in their responses to emotional or spiritual satisfaction, EVs in the cultural sector are more heterogeneous in their motivations. Helping others may be a motivation for some, but accomplishment (looking for something fun and challenging), socializing (working with others, being part of the community), and skill development (using my skills) are comparable or even more meaningful motivations. However, some of these motives are not significant motivators for cultural EVs to return to volunteer. “I was able to use my skills” even has a negative effect on the returnability of EVs at cultural events. This finding is in line with those of Campbell (2009) and Handy et al. (2006), who showed that using skills is not a preeminent motive among cultural EVs.

To more closely examine the motivations of EVs at cultural events, we conducted a logistic regression analysis with the willingness to engage in EVs in the future as the dependent variable. Findings from this analysis reveal a more general distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic motivations. Volunteering “to have fun” and “obtain emotional satisfaction” exerts a significant positive influence on willingness to volunteer as an EV in the future. These findings suggest that EVs are intrinsically motivated and are engaged out of personal interest. In contrast, “meeting new people” has a significant negative effect on professed future engagement in episodic volunteering. We might speculate that episodic volunteering may lead to a saturation of the more extrinsic motivations, such as fulfilled requirements or number of new contacts made, which reduces the felt need for future engagement in episodic volunteering.

Conclusion

In the absence of EVs, many events in both the cultural and social sectors would not be possible. Understanding the motivations of EVs and providing appropriate incentives are therefore essential for the successful organization of these events. Thus, from a practical perspective, the need exists for a better understanding of this growing type of volunteering.

Before presenting implications for research and practice based on this study, we need to emphasize its limitations. First, as this study is based on a survey, there might be social desirability bias in the data. The fact that the respondents were able to remain anonymous should prevent this for the most part, but further research could include a social desirability marker. Second, the respondents in this study come from 15 countries with different cultures and traditions, leading to a heterogeneous sample of respondents. Volunteering might not be equally common in all countries involved, and the types of events might differ as well. Nevertheless, we see a strength in including data from several countries to mitigate country-specific traditions that might reduce the general insight from the results. Third, our study uses a dichotomous categorization of motives. Further research could utilize a more sensitive categorization of motives. Fourth, as our sample was not a randomized or representative sample in any of the participating countries, inferences to the overall population should be taken with some caution. Finally, most items on motivation showed moderate or even negative general responses. Hence, the results may not be used to draw conclusions on EVs’ general motivations. However, our main interest was in the differences between and within groups.

Our study offers new avenues for further research and provides implications for the management of EVs in the cultural sector. First, we extend the understanding of different motives of EVs in distinct sectors of activity. Whereas EVs in the social sector show higher consistency in motivators, EVs for cultural events and activities are more heterogeneous in their motivations. Additionally, the potential for the future engagement of cultural EVs in episodic volunteering appears to be increased by intrinsic motivations and decreased by more extrinsic motivations. Future research should further elaborate on the negative effects of extrinsic incentives, as these may diminish the future pool of volunteers (Hager & Brudney, 2011). This study did not analyze the recruitment strategies of event organizers nor EVs’ perceptions of them. This focus would make a valuable addition to the present study because it would help to increase the understanding of whether EVs engage from their own impulses or if they need external overtures to be prompted. Studies using experimental designs could test whether psychological theories such as nudging are applicable to attract EVs (Moseley & Stoker, 2013). Additionally, we call for further research on the uniqueness of episodic volunteer engagement, returnability, and spillover effects for regular volunteering. Is volunteering for the same event every year still episodic from the perspective of the volunteer, and what does it mean if the episodes become more frequent but not regular?

Although the multinational project of which this study is a part was not able to obtain information from organizers of episodic volunteering events, we may suggest some conclusions for the practical management of EVs. Since cultural EVs are significantly younger and have lower income on average than social EVs, volunteer managers at cultural events have to consider these factors when developing volunteer schedules and incentives. Younger volunteers have age-specific emotional and social needs and thus differ in their motivations from other groups of volunteers (Katz & Sasson, 2019), which is also shown by the higher importance of socializing for cultural EVs. Additionally, the alignment of volunteer and organizational values is crucial for successful collaboration (Brudney & Meijs, 2009; Studer & von Schnurbein, 2013). Younger age may be a reason why fewer individuals have volunteered on a regular basis prior to their EV engagement and can also offer an incentive to retain these volunteers for more regular assignments, since they do not have other volunteering commitments as yet.

Our study shows that, in comparison with social EVs, some extrinsic motivations (e.g., meeting new people or the ability to use skills) play a more significant role for cultural EVs, thus supporting a giving-and-getting dimension or transactional character of volunteering. However, while these extrinsic motivations may motivate initial volunteer engagement, the results of the regression analysis show that they negatively influence the decision to return as a volunteer to a similar event. Especially in the face of increased reliance on volunteers in the cultural sector, it is important to understand the characteristics, motives, and impact of motives of volunteers attracted to cultural and artistic spaces, as “the typical volunteer organization recruits through its existing volunteers; these volunteers tend to recruit people who are similar to them” (Treuren, 2014, p. 66). If we assume that EVs are producing a good (their volunteer task) and consuming at the same time, in line with research on experiential consumption (Holbrook & Hirschman, 1982), it is crucial to understand their preferences with respect to consumption, i.e., their interest and attraction to episodic volunteering in the cultural space, as this consumption might be saturated more or less quickly.

Notes

Some questions were omitted if they were not relevant to a country (e.g., "type of settlement"), whereas other questions included more detailed answer categories (e.g., “race/ethnicity”) if applicable to a country-specific context.

References

Amabile, T. M. (1993). Motivational synergy: Toward new conceptualizations of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation in the workplace. Human Resource Management Review, 3(3), 185–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/1053-4822(93)90012-S

Andreoni, J. (1990). Impure altruism and donations to public goods: A theory of warm-glow giving. Economic Journal, 100(401), 464–477. https://doi.org/10.2307/2234133

Ariza-Montes, A., Roldán-Salgueiro, J. L., & Leal-Rodríguez, A. (2015). Employee and volunteer: An unlikely cocktail? Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 25(3), 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21121

Bang, H., Alexandris, K., & Ross, S. D. (2009). Validation of the revised volunteer motivations scale for international sporting events (VMS-ISE) at the Athens 2004 Olympic Games. Event Management, 12(3–4), 119–131. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599509789659759

Brudney, J. L., & Meijs, L. C. P. M. (2009). It ain’t natural: Toward a new (natural) resource conceptualization for volunteer management. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(4), 564–581. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009333828

Burani, N., & Palestini, A. (2016). What determines volunteer work? On the effects of adverse selection and intrinsic motivation. Economics Letters, 144, 29–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2016.04.014

Campbell, A. (2009). The importance of being valued: Solo “grey nomads” as volunteers at the National Folk Festival. Annals of Leisure Research, 12(3–4), 277–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2009.9686825

Cappellari, L., Ghinetti, P., & Gilberto, T. (2007). On time and money donations (CESifo Working Paper No. No. 2140). Munich.

Chacón, F., Gutiérrez, G., Sauto, V., Vecina, M. L., & Pérez, A. (2017). Volunteer functions inventory: A systematic review. Psicothema, 29(3), 306–316.

Clary, E. G., Snyder, M., & Stukas, A. A. (1996). Volunteers’ motivations: Findings from a national survey. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 25(4), 485–505. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764096254006

Cnaan, R. A., & Goldberg-Glen, R. S. (1991). Measuring motivation to volunteer in human services. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 27(3), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886391273003

Cnaan, R. A., Heist, H. D., & Storti, M. H. (2017). Episodic volunteering at a religious mega event: Pope Francis’s visit to Philadelphia. Nonprofit Management & Leadership, 28(1), 85–104. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21268

Cnaan, R. A., Meijs, L. C. P. M., Brudney, J. L., Hersberger-Langloh, S., Okada, A., & Abu Rumman, S. (2021). You thought that this would be easy? Seeking an understanding of episodic volunteering. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00329-7

Deci, E. L. (1971). Effects of externally mediated rewards on intrinsic motivation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 18(1), 105–115. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0030644

Dickson, L.-A. (2018). Episodic volunteer management at festivals: The case of Valletta Film Festival, Valetta, Malta. In D. Stevenson (Ed.), Managing organisational success in the arts (1st Editio). Routledge.

Dunn, J., Chambers, S. K., & Hyde, M. K. (2016). Systematic review of motives for episodic volunteering. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27(1), 425–464. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-015-9548-4

Erasmus, B., & Morey, P. J. (2016). Faith-based volunteer motivation: Exploring the applicability of the volunteer functions inventory to the motivations and satisfaction levels of volunteers in an australian faith-based organization. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 27, 1343–1360. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-016-9717-0

Finkelstein, M. A. (2008). Volunteer satisfaction and volunteer action: A functional approach. Social Behavior and Personality, 36(1), 9–18. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.1.9

Finkelstein, M. A. (2009). Intrinsic vs. extrinsic motivational orientations and the volunteer process. Personality and Individual Differences, 46(5–6), 653–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2009.01.010

Freitag, M., Manatschal, A., Ackermann, K., & Ackermann, M. (2016). Freiwilligen-monitor schweiz 2016. Seismo Verlag.

Gage, R. L., & Thapa, B. (2012). Volunteer motivations and constraints among college students: Analysis of the volunteer function inventory and leisure constraints models. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 41(3), 405–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764011406738

Ganesh, S., & McAllum, K. (2012). Volunteering and professionalization: Trends in tension? Management Communication Quarterly, 26(1), 152–158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0893318911423762

Gray, E., Khoo, S. E., & Reimondos, A. (2012). Participation in different types of volunteering at young, middle and older adulthood. Journal of Population Research, 29(4), 373–398. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12546-012-9092-7

Grønbjerg, K. A., & Never, B. (2004). The role of religious networks and other factors in types of volunteer work. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 14(3), 263–289. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.34

Güntert, S. T., Neufeind, M., & Wehner, T. (2015). Motives for event volunteering: Extending the functional approach. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 44(4), 686–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014527797

Hackl, F., Halla, M., & Pruckner, G. J. (2010). Volunteering and the state. Public Choice, 151, 465–495. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9754-y

Hager, M. A., & Brudney, J. L. (2011). Problems recruiting volunteers: Nature versus nurture. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 22(2), 137–157. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.20046

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2014). Multivariate data analysis (7th ed.). Pearson.

Handy, F., Brodeur, N., & Cnaan, R. A. (2006). Summer on the island: Episodic volunteering. Voluntary Action, 7(1), 31–42.

Handy, F., Cnaan, R. A., Hustinx, L., Kang, C., Brudney, J. L., Haski-Leventhal, D., Holmes, K., Meijs, L. C., Pessi, A. B., Ranade, B., Yamauchi, N., & Zrinscak, S. (2010). A cross-cultural examination of student volunteering: Is it all about résumé building? Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 39(3), 498–523. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764009344353

Haski-Leventhal, D., & Meijs, L. C. P. M. (2011). The volunteer matrix: Positioning of volunteer organizations. International Journal of Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Marketing, 16, 127–137. https://doi.org/10.1002/nvsm.406

Hassanli, N., Walters, T., & Friedmann, R. (2020). Can cultural festivals function as counterspaces for migrants and refugees? The case of the New Beginnings Festival in Sydney. Leisure Studies, 39(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1666296

Heley, J., Yarker, S., & Jones, L. (2019). Policy studies volunteering in the bath? The rise of microvolunteering and implications for policy. Policy Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2019.1645324

Hogg, E. (2016). Constant, serial and trigger volunteers: Volunteering across the lifecourse and into older age. Voluntary Sector Review, 7(2), 169–190. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080516X14650415652302

Holbrook, M. B., & Hirschman, E. C. (1982). The experiential aspects of consumption: Consumer fantasies, feelings, and fun. Journal of Consumer Research, 9(2), 132. https://doi.org/10.1086/208906

Holdsworth, C. (2010). Why volunteer? Understanding motivations for student volunteering. British Journal of Educational Studies, 58(4), 421–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2010.527666

Hustinx, L., Haski-Leventhal, D., & Handy, F. (2008). One of a kind? Comparing episodic and regular volunteers at the Philadelphia Ronald McDonald house. IJOVA: International Journal of Volunteer Administration, 25(3), 50–66.

Hustinx, L., Shachar, I. Y., Handy, F., & Smith, D. H. (2016). Changing nature of formal service program volunteering. In D. H. Smith, R. A. Stebbins, & J. Grotz (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of volunteering, civic participation, and nonprofit associations (pp. 349–365). Palgrave Macmillan.

Hyde, M. K., Dunn, J., Bax, C., & Chambers, S. K. (2016). Episodic volunteering and retention: An integrated theoretical approach. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014558934

Hyde, M. K., Dunn, J., Scuffham, P. A., & Chambers, S. K. (2014). A systematic review of episodic volunteering in public health and other contexts. BMC Public Health, 14(992), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-992

Katz, A. S., Brisbois, B., Zerger, S., & Hwang, S. W. (2018). Social impact bonds as a funding method for health and social programs: Potential areas of concern. American Journal of Public Health, 108(2), 210–215. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2017.304157

Katz, H., & Sasson, U. (2019). Beyond universalistic motivations: Towards an adolescent volunteer functions inventory. Voluntary Sector Review, 10(2), 189–211. https://doi.org/10.1332/204080519X15629379320509

Krause, N., & Rainville, G. (2018). Volunteering and psychological well-being: Assessing variations by gender and social context. Pastoral Psychology, 67(1), 43–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-017-0792-y

Kreutzer, K., & Jäger, U. (2011). Volunteering versus managerialism: Conflict over organizational identity in voluntary associations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 40(4), 634–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764010369386

Kühnlein, I., & Böhle, F. (2002). Motive und Motivationswandel des bürgerschaftlichen Engagements. In Bürgerschaftliches Engagement und Erwerbsarbeit (pp. 267–297). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Lee, Y. J., & Brudney, J. L. (2009). Rational volunteering: A benefit-cost approach. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 29, 512–530. https://doi.org/10.1108/01443330910986298

Lockstone-Binney, L., Holmes, K., Smith, K., & Baum, T. (2010). Volunteers and volunteering in leisure: Social science perspectives. Leisure Studies, 29(4), 435–455. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2010.527357

Mayer, K. U. (2004). Whose lives? How history, societies, and institutions define and shape life courses. Research in Human Development, 1(3), 161–187. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427617rhd0103_3

Meier, S., & Stutzer, A. (2008). Is volunteering rewarding in itself? Economica, 75(297), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0335.2007.00597.x

Moseley, A., & Stoker, G. (2013). Nudging citizens? Prospects and pitfalls confronting a new heuristic. Resources, Conservation and Recycling, 79, 4–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resconrec.2013.04.008

Musick, M. A., & Wilson, J. (2008). Volunteers—A social profile. Indiana University Press.

Okun, M. A., & Schultz, A. (2003). Age and motives for volunteering: Testing hypotheses derived from socioemotional selectivity theory. Psychology and Aging, 18(2), 231–239. https://doi.org/10.1037/0882-7974.18.2.231

Omoto, A. M., & Snyder, M. (1995). Sustained helping without obligation: Motivation, longevity of service, and perceived attitude change among AIDS volunteers. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68(4), 671–686. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.4.671

Onyx, J., Maher, A., & Leonard, R. (2007). Constructing short episodic volunteering experiences: Matching grey nomads and the needs of small country towns. Third Sector Review, 13(2), 121–139.

Rimes, H., Nesbit, R., Christensen, R. K., & Brudney, J. L. (2017). Exploring the dynamics of volunteer and staff interactions: From satisfaction to conflict. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 28(2), 195–213. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.21277

Ruiter, S., & De Graaf, N. D. (2006). National context, religiosity, and volunteering: Results from 53 countries. American Sociological Review, 71, 191–210. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100202

Ruxton, G. D. (2006). The unequal variance t-test is an underused alternative to Student’s t-test and the Mann-Whitney U test. Behavioral Ecology, 17(4), 688–690. https://doi.org/10.1093/beheco/ark016

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25, 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

Snyder, M., & Omoto, A. M. (2008). Volunteerism: Social issues perspectives and social policy implications. Social Issues and Policy Review, 2(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-2409.2008.00009.x

Son, J., & Wilson, J. (2012). Volunteer work and hedonic, eudemonic, and social well-being. Sociological Forum, 27(3), 658–681. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1573-7861.2012.01340.x

Starnes, B. J., & Wymer, W. W., Jr. (2001). Conceptual foundations and practical guidelines for retaining volunteers who serve in local nonprofit organizations. Journal of Nonprofit & Public Sector Marketing, 9(1–2), 97–118. https://doi.org/10.1300/J054v09n01_05

Studer, S., & von Schnurbein, G. (2013). Organizational factors affecting volunteers: A literature review on volunteer coordination. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 24, 403–440. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-012-9268-y

Studer, S. (2016). Volunteer management: Responding to the uniqueness of volunteers. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(4), 688–714. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764015597786

Stukas, A. A., Hoye, R., Nicholson, M., Brown, K. M., & Aisbett, L. (2016). Motivations to volunteer and their associations with volunteers’ well-being. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 45(1), 112–132. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764014561122

Trautwein, S., Liberatore, F., Lindenmeier, J., & von Schnurbein, G. (2020). Satisfaction with informal volunteering during the COVID-19 crisis: An empirical study considering a Swiss online volunteering platform. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 49(6), 1142–1151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0899764020964595

Treuren, G. J. M. (2014). Enthusiasts, conscripts or instrumentalists? The motivational profiles of event volunteers. Managing Leisure, 19(1), 51–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2013.849506

Ullah Butt, M., Hou, Y., Soomro, K. A., & Maran, D. A. (2017). The ABCE model of volunteer motivation. Journal of Social Service Research, 43(5), 593–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2017.1355867

Wilson, J. (2000). Volunteering. Annual Review of Sociology, 26, 215–240. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.215

Wolff, N., Weisbrod, B. A., & Bird, E. J. (1993). The supply of volunteer labor: The case of hospitals. Nonprofit Management and Leadership, 4(1), 23–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/nml.4130040104

Yates, F. (1984). Test of significance for 2 × 2 contingency tables. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society. Series A (General), 147(3), 426. https://doi.org/10.2307/2981577

Funding

Open Access funding provided by Universität Basel (Universitätsbibliothek Basel). This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Hersberger-Langloh, S.E., von Schnurbein, G., Kang, C. et al. For the Love of Art? Episodic Volunteering at Cultural Events. Voluntas 33, 428–442 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00392-0

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00392-0