Abstract

Numerous philosophers accept the differentiation condition, according to which one does not see an object unless one visually differentiates it from its immediate surroundings. This paper, however, sounds a sceptical note. Based on suggestions by Dretske (2007) and Gibson (2002 [1972]), I articulate two ‘principles of occlusion’ and argue that each principle admits of a reading on which it is both plausible and incompatible with the differentiation condition. To resolve the inconsistency, I suggest we abandon the differentiation condition.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Cephalopods are masters of camouflage. A few years ago, I spotted a small cuttlefish in the Ionian Sea, just off the coast of mainland Greece. As I was watching, the animal moved on top of a large rock and immediately assumed the precise colours and (apparently) texture of the rock. The cuttlefish I had seen a moment before seemed to have vanished, although I knew it had to be lodged somewhere on the rock. (I later confirmed this by approaching the rock. At a certain point, the cuttlefish materialized in front of my eyes, only to shoot through the water a fraction of a second later.)

Did I see the animal when it was lodged on top of the rock? The cuttlefish certainly met some necessary conditions for being seen. In particular, it seems that no matter how we try to specify the causal role an object has to play in order to be seen, the cuttlefish did (or could) play that role. For example, it clearly occupied the right place in the causal nexus (unlike, say, the neuronal activity in my visual area V1 at the time) (cf. Tye, 1982). The cuttlefish reflected light that hit my retinae, no ‘deviant’ causal chains were involved, and so on. Moreover, the cuttlefish must have looked some way to me when it was sitting there on the rock– it must have looked greyish and greenish, and of course uncannily like the surrounding rock.Footnote 1

Of course, I did not identify anything as a cuttlefish as I was staring intensely at the rock. But that does not entail that I did not see a cuttlefish. This point is brought home by another cephalopod encounter, related by Peter Godfrey-Smith, in which a wary cuttlefish, upon seeing Godfrey-Smith, fled ‘into a flat channel with a few rocks strewn around’ (Godfrey-Smith, 2016, 123). Knowing that cuttlefish can disguise themselves as rocks, Godfrey-Smith was ‘positively expecting to find him somewhere trying to be a rock. There was a small rock in the middle of the channel. I looked and thought: well, that one is just a rock’ (ibid.). After swimming to the other end of the channel, finding nothing there, Godfrey-Smith returned to the rock in the middle.

Looking closer, it was the cuttlefish. Once it was apparent that I was fixated on him, he gave up the rock camouflage and wandered back into his dark pink. So there I was, looking for a small cuttlefish looking like a rock, in that exact spot, but he fooled me anyway. (ibid.)

Just like me in the Ionian see, Godfrey-Smith initially failed to identify anything in his surroundings as a cuttlefish. But he did not fail to see the cuttlefish. He evidently did see it, for he initially concluded that it– that thing he saw in the middle of the channel– had to be a rock. If it seems intuitively right to say that I, by contrast, did not see the cuttlefish before my eyes, it is arguably because we subscribe to something like the Differentiation Condition on object-seeing:

Differentiation Condition (DC): If a subject, S, sees an object, x, S visually differentiates x from its immediate surroundings.Footnote 2

Godfrey-Smith had no trouble differentiating the animal from its surroundings, although he did not initially recognize it for what it was. By contrast, until I dove down to the rock, I did not (and could not) visually pick out the cuttlefish lodged there. Hence, by DC, I did not see it.

Many philosophers accept DC,Footnote 3 and it is a thesis of some importance. If DC is true, the prospects of articulating a Causal Theory of Perception that lives up to Grice’s (1961) original ambitions are bleak. For as we have just seen, it seems plausible that perfectly camouflaged objects can meet all the requirements for the ‘right’ causal role. And so, if DC is true, the fact that an object plays that role cannot be sufficient for the object to be seen.

I think DC is false, however. As I argue in this paper, DC is incompatible with two plausible ideas– or ‘principles’, as I shall call them– concerning perceptual occlusion.

Since human environments tend to be ‘cluttered’, as Gibson (1986, 78) put it, perceptual occlusion is ubiquitous. We rarely see an object that does not block our view of something or other, if only part of the horizon or of the blue (or grey) sky. Now, Fred Dretske has proposed that if an object, x, blocks S’s view of another object, y, S must see x (Dretske, 2004, 2007). As far as I am aware, this proposal has received no attention in the philosophical literature. Yet Dretske’s proposal is clearly inconsistent with the differentiation condition: just assume that the occluding object, like my Ionian cuttlefish, is perfectly camouflaged in such a way as to blend in seamlessly with its surroundings. If S needs to visually differentiate x in order to see it, S does not see x; but if Dretske is right, she does.

Another occlusion principle– although not due to a philosopher stricto sensu– has caused a few ripples to appear in the philosophical pond (but for the wrong reasons, I will suggest). Gibson has suggested that if one perceives the occlusion of something, one sees that which is occluded (Gibson, 2002 [1972]). The philosophical verdict has been that Gibson’s proposal is false (Nanay, 2010) or at least not true without qualification (Briscoe, 2011). I disagree. If read the right way– which may admittedly differ from Gibson’s intentions– what Gibson says is most likely true. Moreover, Gibson’s proposal is again inconsistent with the differentiation condition.

Dretske’s and Gibson’s occlusion principles compel us to consider carefully the plausibility of the widespread idea that differentiation is a necessary condition for object-seeing. When we do this, we realize that the idea rests on shaky ground. Or so I shall argue.

In the next section, I try to make precise the notion of perceptual occlusion. Section 3 introduces Dretske’s principle and suggests that, on one reading, it is false. Section 4 develops another reading of Dretske that avoids the problems encountered by the first reading. In Sect. 5, I introduce Gibson’s occlusion principle and suggest that on the most natural reading, it is likely false. Section 6 develops another reading on which the proposal both seems true and is incompatible with the differentiation condition. Finally, in Sect. 7, I argue that it is the differentiation condition that has to go.

2 Perceptual occlusion

The term ‘occlusion’ was introduced by Gibson and colleagues in an influential 1969 paper. They highlighted two necessary conditions for perceptual occlusion. First: ‘Occlusion… entails one thing in front of another, or one surface in front of another, with reference to a point of observation’ (Gibson et al., 1969, 113). Clearly, however, the geometrical fact that something is in front of something else is not sufficient to make the former occlude the latter. My spectacles do not block my view of the surroundings, but reveal them to me in full resolution. More strikingly, things need not be occluded by opaque objects positioned in front of them. Air can bend light around the curvature of the earth in such a way that we can see the rising sun while it is still ‘hidden’ behind the earth, geometrically speaking.Footnote 4

This illustrates the need for a second condition proposed by Gibson and colleagues: an object that is occluded relative to an observer is not ‘projected by light to the [observer]’s point of view’ (ibid.).Footnote 5 The reason my spectacles do not occlude things is that they do not prevent the light reflected off things from reaching my eyes. But just like the first, purely geometrical condition, the second condition is clearly not sufficient. As Gibson et al. emphasize, there is more than one way in which an object can fail to be ‘projected by light’: the object can cease to exist, or there may be no light for it to reflect. In neither case are we tempted to say the object in question is occluded, for it is not hidden because of the presence of some other object. Rather, it is ‘unprojected’ because of absences– of light, or of the object itself.

The case in which light is absent also shows that the conjunction of the two conditions cannot be sufficient for occlusion. In a pitch-dark room, x can be in front of y relative to my point of observation, and no light from y will reach that point; but x does not occlude y. For x to occlude y, it must be x that prevents y from being projected by light to my point of observation.

Moreover, x must do so directly. What I mean by this is that x must be the object that blocks the photons that, had they reached my eyes, would have enabled me to see y. In a loose sense, you may be said to occlude an object for me if you press a button that causes an opaque screen to appear between the object and me.Footnote 6 But you do not directly prevent y’s light from reaching me: it is the screen the photons hit, not you.

To sum up, we may take Gibson et al. to be suggesting the following necessary conditions for occlusion:

x occludes y relative to S’s point of observation only if:

- (1)

x is in front of y relative to S’s point of observation;

- (2)

x directly prevents y from being projected by light to S’s point of observation.

Call (1) ‘the geometrical condition’ and (2) ‘the causal condition’. We should not accept these Gibsonian conditions without qualification. First, Roy Sorensen (1999, 2008) has argued that the geometrical condition is violated in some bona fide cases of occlusion involving backlit objects. In such scenarios, Sorensen maintains, it is the object in front that is occluded by the object behind it. Now, as it happens, there are cases in which the front object hides the object behind it, even in backlit conditions– such as when a large object is placed in front of a smaller one (cf. Overgaard, 2023). But be that as it may, Sorensen is right to suggest that in conditions of backlighting, you need not place the smaller object behind the larger one to hide the former. You can also hide the smaller object by placing it in front of the larger object: the smaller object is now enveloped in– and rendered invisible by– the shadow cast by the larger object (Sorensen, 2008, 25). If this is genuine perceptual occlusion, then condition (1) is not necessary.

We do not need to turn to cases involving backlighting to cast doubt on the necessity of (1), however. Consider again the bending of light waves. We have seen that light coming from one object may bend around another object that, geometrically speaking, ought to occlude the first object. But then it also ought to be possible, at least in principle, for an object to be occluded by another object that it not positioned in front of the first, geometrically speaking (see Fig. 1).

The geometrical condition, then, is not strictly necessary– even though it is arguably met in most cases involving occlusion. What about the causal condition? First of all, the Gibsonian phrase ‘projected by light’ seems best fitted for objects that reflect or emit light. It works less well for objects that absorb light (matte, black objects), yet such objects can be seen, too, and they can be occluded. Moreover, in backlit conditions, we do not see objects in virtue of light they reflect, emit, or absorb. We see them in virtue of the light they block (cf. Sorensen, 2008, 48). In a backlit scenario, in which a small object is hidden in front of a larger object, the latter occludes the former by preventing it from blocking light headed in S’s direction. If this is genuine occlusion, we must ensure the causal condition accommodates it.

Although I think it is possible to interpret the phrase ‘projected by light’ liberally such that it covers all the mentioned cases, I propose to sidestep these complications by simply restricting my discussion to situations in which objects are front-lit and reflect light.Footnote 7 The claim, then, would not be that Gibson’s conditions are necessary tout court, but that they are necessary in front-lit environments involving objects that reflect light.

Secondly, condition (2) would have to be amended in some way to make room for cases of partial occlusion, in which not all of the light reflected off an object is blocked before it reaches S. My discussion– save for a brief appearance of partial occlusion in Sect. 6– will be restricted to total occlusion, however. And so I propose to leave (2) as it is, with the proviso that it is only valid for total occlusion.

Finally, we must consider a more radical objection. John Hyman has argued that occlusion is ‘not a causal notion’ at all (Hyman, 1993, 213). If this is right, it seems we do not need to modify condition (2) or restrict its application– we need to eliminate it altogether.

A closer look at Hyman’s argument does not seem to licence his strong conclusion, however. Hyman starts from the assumption that it is ‘unreasonable to call blocking [i.e., occlusion] “a causal notion” unless “y block’s S’s view of x” entails “y causes S not to see x”’ (Hyman, 1993, 213). He then rejects the entailment on the grounds that what y’s occlusion of x causes is at most the non-existence of a certain sort of opportunity for S– the opportunity to see x. But to cause that opportunity not to arise is not the same as causing S not to see x, any more than my opening of a door causes S not to open it. In both cases, S is deprived of a certain opportunity– to see x, to open a door (without first closing it). But S is not caused not to do what S might have done had she not been deprived of that opportunity. This is all fine, as far as it goes, but it only establishes that occlusion is not a causal notion given Hyman’s starting assumption. And that assumption seems unmotivated. If occlusion entails the causation of a situation in which a certain opportunity does not exist, then it does seem perfectly legitimate to call it ‘a causal notion’.

A further question is whether the causal condition is also sufficient for perceptual occlusion. It seems to me it is not. It could be met in a case in which S is blind. But we would not be inclined to say that x can occlude y for a subject that is unable to see things in the first place. This is connected with the point just made about certain opportunities being closed off. If S is blind, the fact that x blocks light reflected off y that might otherwise have made it to S’s eyes cannot cause an opportunity to see y to be closed off. For that opportunity is non-existent from the outset. To revert to Hyman’s image again: just as you cannot open a door that is already open, you cannot close one that is already closed (without opening it first, of course).

So, to get something that might constitute a sufficient condition, we need to assume that S is capable of seeing objects whose light reach her point of observation. With that assumption in place– and bearing in mind the limitations already mentioned– the causal condition is both necessary and sufficient for occlusion. So I shall assume, at any rate, and I shall work from that assumption in the remainder of this paper.

Equipped with this more precise grasp of occlusion, let us turn to Dretske’s proposal concerning perception and occlusion.

3 Dretske’s occlusion principle, first pass

Look at a small object– for example, a pencil– in your immediate vicinity. Then hold up another, larger object– such as a book– between your eyes and the first object. The book now blocks the light reflected off the pencil and travelling in your direction, preventing you from seeing the pencil. Hence, the book occludes the pencil. Another fact about the situation is worth highlighting: whereas you do not now see the pencil, you do see the object responsible for the occlusion of it. You see the occluder.

Fred Dretske– prominent erstwhile defender of DC– came to reject DC because he took it to be a general principle that an occluding object must be seen. Discussing an example where you fail to notice a friend in a crowded marketplace although he is in plain view, Dretske writes: ‘You certainly didn’t see through [your friend]. You didn’t, for instance, see the apples on the stand directly behind him. The reason you didn’t see the apples is because he was in front of them, blocking your view of them. So you must have seen him’ (Dretske, 2007, 217). Let the phrase ‘x occludes y for S’ be strictly equivalent with ‘x blocks S’s view of y’.Footnote 8 Dretske then seems to defend the following principle:

Dretske’s Occlusion Principle,Footnote 9First Pass (DOP1): If x occludes y for S, S sees x.

DOP1 has obvious implications for DC. For consider our perfectly camouflaged cuttlefish again. Lodged there on the rock, it occludes part of the rock. If so, then by DOP1, I see the cuttlefish. And if I see a perfectly camouflaged object that I cannot differentiate from its immediate surroundings, DC must be false. Dretske accepts these implications. As he writes,

if you paste a white sheet of paper on a matching white wall (perfect camouflage) so that people cannot distinguish the paper from its surroundings (cannot, that is, see where it is) do they nonetheless see the paper? Yes. They certainly see something in that part of the wall. It isn’t the wall behind the paper. What else is left? (Dretske, 2007, 229)Footnote 10

I shall return to the anti-DC intuitions Dretske appeals to here towards the end of the paper. But for now, the point is simply that– as Dretske recognizes– if DOP1 is true, DC is false.

Unfortunately, DOP1 is false as it stands. Consider the fact that human environments not only tend to be cluttered– they tend to be very cluttered. That is to say, objects not only become hidden (wholly or in part) behind other objects; those other objects can themselves become hidden behind yet other objects, and so on.

Suppose that you see an object, c, in perfectly normal viewing conditions (no unusual bending of light, etc.). As you are looking at c, another, larger object, b, enters the scene and moves in front of c, blocking your view of the latter. The situation now is as depicted in Fig. 2.

But now suppose a third and even larger object, a, comes to be positioned in front of b (Fig. 3) in such a way as to occlude b. The question I want to raise, however, is whether a will also occlude c.

Perhaps someone might be tempted to reject this question out of hand. Perhaps, so they might reason, the concept of ‘occlusion’– designed as it presumably was to apply to simpler cases of the sort depicted in Fig. 2– does not apply to such a complex case. But this suggestion seems hopeless. First, a incontestably does occlude something in the complex case: it occludes b. Second, there is no question that c is occluded. In the situation depicted in Fig. 3, you cannot see c. But the problem is not that c is too far away to be seen, or that it is camouflaged, or that viewing conditions are poor, or whatever. Rather, you cannot see c because it is occluded– blocked from view by something else.

So what is that ‘something’ that occludes c? We seem to have three options: a, b, or both. Since each of a and b is sufficient on its own to occlude c, to say that both a and b occlude c is not to say that they only manage to do so in tandem– the way two semi-transparent curtains may manage to conceal an object that would still be discernible behind one such curtain. Rather, it is to say that a by itself occludes c, as does b– so that c is occluded twice over, as it were.

Suppose we say that b occludes c (either alone or alongside a). We see immediately that DOP1 must be false. For b is itself entirely invisible, occluded as it is by a. If b nevertheless occludes c, it cannot be sufficient for seeing x that x occludes y– contra DOP1.

To save DOP1, then, we have to assume that only a occludes c. But this assumption violates our causal condition.Footnote 11 When asking whether a occludes c we are asking whether a prevents c from being ‘projected by light’, as Gibson put is, to an observer’s ‘station point’. But it seems clear that, whereas a blocks the light reflected off b and hence is responsible for the occlusion of b, a has no hand in the blocking of light from c. The photons bouncing off c and travelling in the direction of the observer are all blocked by b before they can reach a. The suggestion that only a occludes c is absurd: a makes no contribution whatever to the occlusion of c.Footnote 12

4 Dretske’s occlusion principle, second pass

Perhaps DOP1 does not quite capture Dretske’s intentions, however. In his example of the friend in the crowded marketplace, Dretske says ‘the reason’ you do not see the apples is that your friend blocks your view of them. This suggests the following counterfactual: had your friend not occluded the apples, you would have seen them. Other formulations of Dretske’s indicate that indeed he has in mind a scenario in which that counterfactual holds: ‘If [your friend] really did prevent you from seeing the apples, you must have seen him. How else can x block your vision of y?’ (Dretske, 2004, 10; my emphasis). Surely, your friend would not prevent you from seeing the apples unless you would have seen them were it not for him.

The following principle, then, seems closer to what Dretske has in mind:

Dretske’s Occlusion Principle, Second Pass (DOP2): If (x occludes y for S, and S would have seen y were it not for x’s occlusion of it), then S sees x.

Is DOP2 true? One thing is clear: the sort of case I considered in the previous section, in which two opaque objects, a and b, are interposed between the observer and c, presents no difficulties for DOP2. For if b had not been there, S still would not have seen c. Since the antecedent of DOP2 is thus false in this case, DOP2 gives us no licence to draw the absurd conclusion that b is seen.

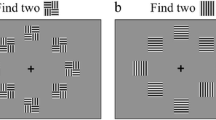

However, DOP2 may seem to be in tension with empirical findings on so-called ‘inattentional blindness’. In one of Simons and Chabris’ (1999) experiments, subjects would watch a recording of basketball game during which a person in a gorilla suit would enter the scene, walk to the centre of the frame, thump her chest, and leave. About half of the test subjects failed to notice any of this. As these and similar findings are commonly interpreted, a large percentage of observers simply fail to see the object of interest (the ‘gorilla’, in this case).Footnote 13

Now consider one of those observers oblivious to the presence of a ‘gorilla’. Suppose the ‘gorilla’ blocks the observer’s view of something– a basketball player, say– at one point. In the video recordings used by Simons and Chabris this in fact happens repeatedly.Footnote 14 On the plausible assumption that, in at least some of the cases in which the ‘gorilla’ occludes a player, the observer would have seen the player if the ‘gorilla’ had not been there, we can now infer from DOP2 that the observer must have seen the gorilla. This contradicts the empirical findings, and so DOP2 is (contingently) false. Or so it might seem.

But things are not that straightforward. What are the grounds for saying that subjects do not see the ‘gorilla’ to begin with? That observers do not report seeing it is proof that they failed to identify anything as a ‘gorilla’. But, as we have seen, this is entirely compatible with them seeing it nonetheless.Footnote 15 Godfrey-Smith would not have reported seeing a cuttlefish if he had only caught a glimpse of it as it was pretending to be a rock– but he would have seen one all the same. Now, it seems all the results tell us is that many people will not report seeing a ‘gorilla’, and are surprised when told that one was present. But if Godfrey-Smith had not been so well-informed about the prowess of cephalopods, he would surely also have been surprised to learn that the ‘rock’ he had been staring at was in fact a cuttlefish.Footnote 16 Thus, it is far from obvious that the inattentional blindness experiments deliver an empirical falsification of DOP2, as the usual interpretation of the findings seems unmotivated.

It is, then, an open question thus far whether DOP2 is true or false. If it false, it is at least not obviously so. And importantly: if DOP2 is true, DC must be false. A perfectly camouflaged cuttlefish can occlude things that S would have seen had the cuttlefish not been there. Thus, by modus ponens from DOP2, we can conclude that S sees the cuttlefish, even though she cannot differentiate it from its immediate surroundings.

5 Gibson’s occlusion principle, first pass

While Dretske’s Occlusion Principle has not– to my knowledge– raised any philosophical eyebrows, another such principle due to Gibson has, but I think for the wrong reason. It is a single remark that has caught philosophers’ attention, and it reads as follows: ‘the perception of occlusion, it seems to me, entails the perception of something which is occluded’ (Gibson, 2002 [1972], 84). I take ‘perception’ to be a determinable and ‘seeing’ to be one of its determinates (others being ‘hearing’, ‘tasting’, etc.). Given this, we may read Gibson as advocating the following principle:

Gibson’s Occlusion Principle (GOP): If S sees the occlusion of x, S sees x.

Bence Nanay takes Gibson to be saying that one may perceive– see– an object or surface entirely hidden from view. Nanay objects that ‘the presence of sensory stimulation’ is a ‘widely accepted necessary condition for perception’ (Nanay, 2010, 242). Hence occluded objects (and surfaces) cannot be seen, contra Gibson (ibid.; cf. Nanay, 2018, 5). Robert Briscoe agrees that we do not see occluded objects and surfaces, but argues that Gibson is nevertheless right to hold that what is occluded is perceptually represented ‘under certain circumstances’ (Briscoe, 2011, 159). His point is that what is visible often contains information that specifies occluded surfaces. Although these surfaces cannot be seen, strictly speaking, they are nevertheless visually represented in some fashion.

Both Briscoe and Nanay thus take GOP to be false as it stands. But I think their verdicts are premature. First, notice that Gibson is not saying that S sees x if x is occluded. If he were, his view would be hopeless– he would have to maintain that S sees c in Figs. 2 and 3, for instance, which is obviously false. Rather, what Gibson says is that if S sees the occlusion of x, then she sees x. Therefore, the question we ought to ask ourselves is what it might mean to see the occlusion of something. It seems to me that there are two possibilities: Either Gibson is talking about the perception of a certain kind of event– in which something becomes occluded– or he is talking about the perception of a certain sort of state– the state of being occluded.

The context of Gibson’s remark on perception and occlusion suggests that he has in mind the latter. ‘I apprehend part of the room as occluded by my head, and part of the lawn as occluded by the edges of the window’, Gibson writes immediately prior to making the remark in question (Gibson, 2002 [1972], 84). He does not talk of these things becoming occluded, say as a result of his movement. He talks about them as already being occluded and apprehended as such.

How can one see the state of being occluded? Gibson’s examples are suggestive, for both are cases of partial occlusion. I see the room I am in– just not the part that is behind my head. Likewise, looking out the window, I see the garden; but I do not see the parts occluded by the edges of the window. This suggests that the paradigmatic– or even only– case in which one may see the occlusion of an object is one in which the object is partially, and not entirely, occluded. But if the antecedent of GOP is only true in certain cases of partial occlusion, it seems GOP does not have the obviously false implications Nanay takes it to have. For when x is only partially occluded by y, presumably there will be sensory stimulation stemming from x. At least this will be so in the sorts of cases we are interested in here– namely cases in which it is also true that the observer sees the partial occlusion of x.Footnote 17

Still, what is it to see x’s state of being occluded? This seems to be a case of ‘seeing-that’ something is thus-and-so, or what Dretske has dubbed ‘epistemic’ seeing (cf. Dretske, 1969, 163).Footnote 18 This gives us:

GOP, First Pass (GOP1): If S sees that x is occluded, S sees x.

GOP1 does not threaten DC, however. For GOP1 is false, at least on a common understanding of the logic of seeing-that. According to many philosophers, it is possible to see that x is thus-and-so without seeing x itself.Footnote 19 For example, I can see that the fuel tank is half-full by looking at the fuel gauge; I do not have to see the tank itself. (In fact, seeing the tank itself would not help unless the tank was transparent.) Dretske collects such cases under the heading of ‘secondary epistemic seeing’ (Dretske, 1969, ch. 4). A ‘secondary’ case of seeing specifically that something is occluded is not too hard to imagine. Suppose there is an ‘occlude-o-metre’ in the upper right corner of my visual field. By looking at it, I can come to know that an object that would be in the lower left corner of my visual field if I directed my gaze accordingly is (partially or wholly) occluded.

Not everyone accepts that there are such cases of ‘secondary epistemic seeing’.Footnote 20 Some maintain that if S sees that x is F, S sees x (e.g., Chisholm, 1957, 164). For the sake of the argument, suppose they are right. GOP1 still does not pose a threat to DC. For seeing that x is thus-and-so, according to a majority of philosophers, implies believing, indeed knowing, that x is thus-and-so.Footnote 21 But if a fish comes to occlude the perfectly camouflaged cuttlefish (whether wholly or in part), I will presumably not believe that it does unless I can determine the cuttlefish’s whereabouts. And even in cases where I do believe the cuttlefish is where it happens to be, and believe correctly that it is occluded, say, I surely cannot be said to know this, as I have no reliable information about the cuttlefish’s precise whereabouts. So, assuming with the majority of philosophers that seeing that x is occluded entails knowing that it is, we cannot generate a conclusion that contradicts DC. Since the cuttlefish is perfectly camouflaged, I cannot know that it is occluded. And so GOP1 does not licence the anti-DC conclusion that I see the cuttlefish.

It is not universally accepted that seeing that x is thus-and-so implies knowing (or even believing) that it is (cf. Pritchard, 2012, 25–34). But to mount a challenge to DC on the basis of GOP1, one must make not one but two controversial assumptions concerning seeing-that: First, to ensure that GOP1 is not obviously false, one must assume that there is no such thing as secondary epistemic seeing. Second, to create a tension between GOP1 and DC, one must assume that seeing-that does not imply knowing-that. That seems to me to be a controversial assumption too many, and so I conclude that GOP1 poses no threat to DC.

6 Gibson’s occlusion principle, second pass

There was, however, another way of reading GOP. We can take GOP to be making a claim about the perception of occlusion events (happenings or occurrences). This is probably not what Gibson had in mind, but it is certainly consistent with our original formulation of GOP. Events are changes or alterations in the states objects are in (cf. Dretske, 1969, 163). So, interpreting GOP in terms of the perception of occlusion events, we get:

If S sees (the event of) x becoming occluded, S sees x.

It is widely accepted that we can see events– to again adopt Dretske’s terminology– ‘non-epistemically’.Footnote 22 That is, I can see the event that is x’s becoming F without knowing– or even believing– that the thing is x or that it is becoming F. Non-epistemic seeing is referentially transparent, as it is sometimes put: We can freely substitute expressions referring to the event S sees without altering the truth-value of the statement that S sees that event. It does not matter whether or not the expressions capture what S makes of the situation. Dogs can see accidents on the M25 although they have no inkling that those occurrences are accidents, or that they are happening on the M25. The animals’ ignorance of motorways and car crashes does not render them blind to such events. If the accident a dog happens to witness on one occasion is the second fatal accident on the M25 in two months, then the dog sees the second fatal accident on the M25 in two months.

Taking GOP to be concerned with the non-epistemic seeing of events, we have:

GOP, Second Pass (GOP2): If S non-epistemically sees (the event of) x becoming occluded, S non-epistemically sees x.

When I discussed GOP1 above, I suggested its scope was likely limited to cases of partial occlusion. Is the scope of GOP2 also limited? I suspect GOP2may be true of all cases of occlusion, partial as well as complete. I shall not attempt to argue for this, however. In fact, I shall restrict the scope of GOP2 to a very limited range of cases: those in which all of x is occluded and only x (i.e., the occluder does not block one’s view of any part of x’s immediate environment). I propose to restrict my defence of GOP2 to such cases of ‘perfect covering’ for two reasons. First, the more restricted the scope of GOP2, the fewer cases (and potential counterexamples) we need to worry about. Second, as we shall see in the next section, severely restricting the scope of GOP2 makes the principle more robust in the face of a certain argument on behalf of DC.

With the restriction in place, GOP2 is beginning to look plausible. The sorts of cases that caused problems for Dretske’s Occlusion Principle, on the first reading of it, have no bite when it comes to GOP2. Suppose you are looking at c, and b arrives, eclipsing c. You see the event or happening that is the occlusion of c, and so GOP2 says you (non-epistemically) see c. But so you do– right up to the point where the event of c becoming occluded is over, and c is in a state of being occluded. When a arrives, you non-epistemically see the occlusion of b, which again licences the perfectly reasonable conclusion that you see b. But the arrival of a does not constitute an opportunity to witness the becoming occluded of c. For c is already occluded.

Cases such as the one illustrated in Fig. 3 raise delicate questions, however, concerning the circumstances in which the antecedent of GOP2 is true. Suppose a and b arrive simultaneously, with b hidden behind a. It will seem to S that she sees the occlusion of c by a. But she cannot, since a does not come to occlude c– b does. And since b is not seen, it seems S cannot see the occlusion of c at all, which is counterintuitive.

I think we should bite the bullet and accept that S does not see the relevant occlusion event. This is not as absurd as it might seem at first blush. After all, what S sees is a moving in front of c, say, but that event is not the occlusion of c. Rather, it is b’s coming to be in front of c that is the occlusion of c. And clearly S does not see that event. However counterintuitive it may seem initially, then, the right thing to say is that I do not see the occlusion of c when it is effectuated by an object that is itself occluded.

If GOP2 is false, it is at least not obviously so. But we have yet to see whether GOP2 has implications for DC. To see that it does, return to our camouflaged cuttlefish (not Godfrey-Smith’s).Footnote 23 Now suppose another, slightly smaller cuttlefish– call it Cully– moves in front of the first cuttlefish– call it Tully– covering it perfectly. Cully’s moving in front of Tully is depicted in Fig. 4.

The end result is that Cully blocks the light reflected off Tully, but does not block any of the light reflected off the surrounding rock, as illustrated in Fig. 5.

Let us assume that this happens in an instantaneous jump from one position– next to the rock– to the position in front of Tully. Suppose S sees this occurrence. It is unquestionably an occurrence in which something becomes occluded: something’s light is being blocked as Cully jumps into place. If S does not know about Tully, she is likely to describe the event in terms of the occlusion of part of the rock. But it cannot be that event S sees, because the relevant portion of the rock is already in a state of occlusion, being covered by Tully. Rather, what becomes occluded– prevented from ‘being projected by light’– is surely Tully. The occlusion of Tully, then, is the event that S sees.

Recall that one can non-epistemically see the event of x becoming F even if one has no inkling that x is there or that it is becoming F. So, the fact that a naïve observer will have no inclination to say that they saw the occlusion of a cuttlefish has no direct bearing on the truth or falsity of the proposition that they did see the occlusion of a cuttlefish (or of that particular cuttlefish– Tully).

If it is accepted that S sees the event that is the occlusion of Tully, then we can infer by modus ponens from GOP2 that S sees Tully. But we have stipulated that Tully cannot be discriminated from its immediate surroundingsFootnote 24 and so, by DC, it cannot be seen. Thus, we have generated a contradiction between GOP2 and DC.

7 The differentiation condition reconsidered

Let us take stock. We have found two occlusion principles that are incompatible with DC. But the incompatibility in and of itself does not tell us whether it is DC or GOP2/DOP2 that has to go. Obviously, it would be question-begging to suggest that DOP2 and GOP2 are false because they are incompatible with DC. The critical target of this paper is DC, and so one is not permitted to take DC as gospel. But neither are we entitled to assume that we have refuted DC merely by dint of finding two plausible-looking principles that contradict it. What we need is some reason to prefer one side to the other.

Philosophers mostly seem to assume that DC is squarely supported by our intuitions. I will examine whether this is in fact so in a moment. But first, let me consider explicit arguments on DC’s behalf. This will not detain us for long, since such arguments are in short supply. Pitson (1984) offers two arguments in support of DC: First, discussing a case in which an object, x, is present within a subject’s visual field, Pitson writes that:

whatever perceptual ‘experience’ S may undergo as a result of the presence of x within his field of vision, it is still in order to ask whether S can see x. And in asking this question we apparently wish to know whether S was successful in discriminating x from among the other objects in its immediate environment. (Pitson, 1984, 122)

Pitson’s point is that unless discriminating x from its immediate environment was a requirement, we could not meaningfully ask whether S can see x, since the question would already be answered affirmatively.

But this assumes that the expression ‘S can see x’ can only refer to the capacity to see x non-epistemically. And that assumption is false. The optician may ask me whether I can see the bottom line on the eye test board. The question is a meaningful one, but not because there is any real issue about whether I can non-epistemically see the bottom line– I am myopic, not blind. The real issue is not whether I can identify the letters either– the optician assumes that I have the ability to identify the various letters, but in principle, you could use the test board to test someone unfamiliar with the Latin alphabet.Footnote 25 The question is whether I can ‘make the letters out’, or whether they are ‘too blurry’. In other contexts, identification or recognition is what is at issue. If I am facing a multitude of reddish birds, and my ornithologist friend asks me whether I can see the jay, the question is whether I can tell which of the birds is a jay. My friend is not wondering whether I might have trouble non-epistemically seeing the bird in question, as though, absurdly, I might be blind to just that species of bird. In yet other contexts, such as those involving a camouflaged x, we can ask whether S can see x, meaning whether S can differentiate x from its immediate surroundings. But the meaningfulness of that question in such a context is no more evidence against S’s non-epistemic seeing of x than the meaningfulness of the optician’s or my friend’s questions is evidence I do not see the bottom line of the eye test board, or the jay.

As it happens, Pitson goes on to acknowledge that we sometimes say that people see things– such as camouflaged animals– that they do not differentiate. But this, he claims, is ‘a degenerate sense of “seeing”’ (Pitson, 1984, 123). This emerges from the ‘fact’ that, in such cases ‘our use of “see” will not bear emphasis’ (ibid.). Pitson illustrates this by pointing out that, in a case of perfect camouflage, ‘it would be misleading to say something like, e.g., “Not only was [x] in view or in sight of [S], but also [S] did see [x]’ (ibid.). This is Pitson’s second argument. Unfortunately, it is no more effective than the first.

We can grant that it is misleading to say that ‘not only was x in view of S, but also S did see x’, and yet refuse to accept that our use of ‘see’ in cases where DC is not met ‘does not bear emphasis’. Instead, what might mislead us here is that ‘but also’ misleadingly suggests that ‘S did see x’ adds new information. Thus, ‘Not only was x in view, but S did see x’ is misleading in the same way as ‘She not only drank the entire pint in one go, but she also downed it’.

Furthermore, and relatedly, to the extent one takes ‘but also S did see x’ as adding new information, one naturally thinks of S’s achievements as having gone beyond the mere non-epistemic seeing of x. Perhaps one thinks of S as having noticed or identified x. But in a typical case of perfect camouflage, S neither notices nor identifies the camouflaged object. So the statement ‘Not only was x in view… etc.’ is doubly misleading: It misleadingly suggests that seeing x is not already implied by having x in view. And, in so doing, it sends us searching for a notion of seeing x that is more demanding than non-epistemic seeing. Hence, Pitson’s arguments are inconclusive.

Siegel (2006) offers the only other explicit argument for DC of which I am aware. Siegel writes: ‘if one sees an object o, one can form a de re mental state about o, or demonstratively refer to o, just by exercising whatever general apparatus is needed for de re mental states or demonstrative reference’ (Siegel, 2006, 432). We are not in a position to form de re thoughts about perfectly camouflaged objects, however, even when we happen to be looking straight at them. Such thoughts are only possible with respect to objects we can visually differentiate from their surroundings (ibid., 434). If Siegel is right, DC should be upheld, and DOP2/GOP2– entailing, as they do, that we see perfectly camouflaged objects like Tully– rejected.

Siegel’s principle that seeing an object is sufficient for being able to form de re thoughts about it has some intuitively pull, but I am not convinced we must accept it.Footnote 26 That depends, it seems to me, on whether or not one may see objects without noticing them at all.Footnote 27

Imagine that you are looking at a hundred football supporters, seated in tiers, and all visible to you from where you stand. You see each one of them. Suppose some of the football supporters look angry, while others do not. Research suggests that angry faces in a crowd ‘pop out’ and are more easily noticed than non-threatening faces.Footnote 28 Perhaps the processing of the angry faces monopolize your cognitive resources and, as a result, one or more individuals with more neutral facial expressions go unnoticed. If one such person disappeared while you were blinking, you might not notice any difference at all. The crowd might seem the same to you. Were you able to form de re thoughts about that individual while she was there, given that (it seems) you did not even notice her? Presumably not.

I am not claiming that these remarks are probative. I am merely suggesting that it is not obvious that Siegel’s principle (S sees x → S can form de re thoughts about x) must be accepted. But there is a second, and equally important point I want to make here: Even if Siegel’s principle is unassailable, we can and should resist Siegel’s further claim that the possibility of de re thoughts about x require that x is visually differentiated.

Consider the perception of Cully’s coming-to-occlude Tully. Seeing that event does put S in a position to entertain de re (and demonstrative) thoughts about Tully, it seems to me. For instance, S can think, of that which the non-camouflaged cuttlefish came to occlude (= Tully), that it is just part of a rock. Being informed by a reliable source that a second, camouflaged, cuttlefish was present in her field of vision, S may think to herself: ‘Well, that which is now hidden behind that cuttlefish [pointing at Cully] was just part of the rock’. At no point is Tully visually differentiated; yet S can still have de re thoughts about it.Footnote 29

If this is right, Siegel’s argument does not establish DC. At least in a case in which a perfectly camouflaged x is exactly occluded, we can have de re thoughts about x (‘that which is now occluded by y’), even though we cannot visually differentiate x. So even if Siegel is right that seeing x entails being able to form de re thoughts about x– which is not obvious– we can still have perception without differentiation in the restricted set of occlusion cases covered by GOP2.

Since I am aware of no other explicit argument for DC, let me now turn to the question of which way our intuitions point. Suppose you are looking straight at camouflaged Tully. It is not as if there is a large, cuttlefish-shaped scotoma in that part– the Tully-occupied part– of your visual field, which magically disappears the moment Cully comes to occupy the relevant spot. No, you certainly see something in that part of your visual field.Footnote 30 What is that something? Obviously, it cannot be part of the rock, occluded as it is by Tully. It is Tully that is projected by light to your retinae– not the rock. So it must be Tully that you see. As Dretske rhetorically asks, ‘What else is left?’ (Dretske, 2007, 229).

Perhaps someone might suggest– contra Dretske– that there is an option left: what you see in the Tully-occupied part of your field of vision is not Tully, but Tully’s camouflaged facing surface. In this vein, Siegel suggests that one may perhaps see a perfectly camouflaged motionless performance artist’s ‘disguised surfaces’ (Siegel, 2006, 434), even though one cannot see the artist himself, DC not being met.

This proposal raises the question of what sorts of things surfaces are.Footnote 31 Cutting a long story short, it seems there are two options: Either an object’s surface is an outer layer of it– i.e., a thin slice of matter– or surfaces are abstract geometrical entities.Footnote 32 If the latter, surfaces cannot be seen, since they cannot play the causal role something has to play in order to be seen. In particular, abstract geometrical objects cannot reflect, block, or absorb light.Footnote 33 So, in order for surfaces to be the sort of thing one can see in cases of perfect camouflage, they must be slices of matter. But then surfaces are essentially ordinary physical objects– comparable to thin sheets of paper glued to walls. As such, they cannot provide a way out for DC advocates. For the thin surface layer of Tully is just as impossible to visually differentiate from its surroundings as Tully herself is. And so it is not consistent with DC to suggest that that surface is seen.

8 Conclusion

To sum up: I have suggested that two occlusion principles– DOP2 and GOP2– are plausible. Since neither principle is consistent with DC, we are compelled to consider the sorts of reasons we have for assuming that DC is true in the first place. I have suggested that those reasons are conspicuously weaker than the intuitions supporting the conclusion that we can see perfectly camouflaged objects. The upshot is that we ought to abandon DC.Footnote 34

Notes

Many defenders of DC accept that the differentiation requirement lapses in cases where an object has no immediate environment from which one might differentiate it (e.g., Dretske, 1969, 26–27; Pitson, 1984, 124; Cassam, 2007, 95). Lying on one’s back, looking at a uniformly blue sky would be a case in point. I shall not discuss such cases in this paper.

See, e.g., Dretske (1969, 20), Pitson (1984), Campbell (2002, 7), Siegel (2006), Cassam (2007, 105), Sorensen (2008, 63), and Matthen (2021). McNeill (2016) is more ambivalent. French (2018) offers some putative counterexamples, but accepts that differentiation may be a requirement in a range of cases, including those involving camouflage. Drawing inspiration from French, Mac Cumhaill (2015) also offers counterexamples to DC.

I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for this example, and for raising a number of critical questions concerning the geometrical condition. See Sorensen (2011) for more trouble cases for the geometrical condition.

The phrasing may be odd, but the point ought to be clear enough. Gibson et al. are of course not suggesting that non-occluded objects are literally projected or transmitted from one place to another, whereas occluded ones stay put, as it were. Rather, the point is that in cases of total occlusion, no light coming from the object reaches the subject’s point of observation. (Here I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer.)

Here I am indebted to an anonymous reviewer.

Even matte, black objects may fit the bill. According to Sorensen, ‘No surface on Earth has zero reflectivity’ (2008, 201).

Thus, ‘for S’ should not be understood as referring to what S makes of the situation, what it feels like for S, or the like. It just means that it is S’s view of y that x blocks, whether or not it seems that way for S, or S realizes that this is so, etc. (I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for prompting me to make this clarification.)

As far as I know, the term ‘occlusion principle’ originates in philosophical discussions of pictorial art (see Hyman, 2000; Derksen, 2004). I use the term in an entirely different context, and I make no claim that my discussion in this paper has implications for the theory of depiction or pictorial experience.

This example mirrors one Dretske discussed in Seeing and Knowing. But there he drew the exact opposite conclusion: since the paper cannot be differentiated from its immediate surroundings, it cannot be seen (Dretske, 1969, 23–24).

An anonymous reviewer suggests that this actually goes to show that the causal condition is flawed. The reviewer proposes instead a counterfactual construal of occlusion on which x occludes y for S if (and only if?) x would cause light from y not to reach S provided nothing else intervened. In the scenario depicted in Fig. 2, b occludes c, because nothing else intervenes and b does block the light from c. However, in the scenario depicted in Fig. 3, a (alongside b?) occludes c, because had b not intervened, a would have blocked the light from c. The counterfactual construal does not work, however. It faces what Frank Jackson calls ‘the usual problem with counterfactual analyses of the categorical’: to say that x occludes y is ‘to say how things are, not how things would be if things were different’ (Jackson, 1977, 84). The problem comes out dramatically in the following variant of the situation depicted in Fig. 3: Suppose a is fully transparent but would instantly become opaque if b were removed. It seems a now meets the condition for occluding c¸ even though (intuitively as well as causally) a does not block one’s view of anything! (Or consider a variant of the situation depicted in Fig. 1, in which the rectangle is moved left so that it occupies a position in the geometrical line of sight, but no longer blocks the (bent) light headed in the subject’s direction. The subject now sees the object, but it is nevertheless true that the rectangle would block the light from the object if the refractive medium did not intervene. So on the counterfactual proposal, we would have to count the object as occluded– yet the subject sees it.) More generally, I struggle to see how the causal condition can be dispensed with. Consider the simple case depicted in Fig. 2. What does b’s blocking S’s view of c amount to if not blocking the light from c? Note, finally, that if I am wrong about all this, it follows that DOP1 is more plausible than I have allowed. If anything, this put another nail in the coffin of DC.

Another ‘occlusion principle’, due to Roy Sorensen, runs into similar problems. Sorensen discusses an example in which a fluorescent balloon drifts in front of the moon, first occluding the edge of the moon, and then the middle. According to Sorensen, ‘if the balloon blocks our view of the middle of the moon, then we must have previously seen the middle of the moon’ (Sorensen, 2008, 50). In reasoning thus, Sorensen seems to be relying on the following principle: if x occludes y for S, S saw y prior to x’s arrival. But this principle seems false: assume that a arrives before b. When b arrives, it alone will meet the causal condition. Thus, b now occludes an object that was already rendered invisible by a. I offer a more extended discussion of Sorensen in Overgaard (2023).

In one of their recordings, only one of the six basketball players is not at one point occluded (wholly or in large part) by the ‘gorilla’ as it makes its way across the scene. See https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vJG698U2Mvo.

It is compatible with them seeing it in the ‘non-epistemic’ sense (Dretske, 1969) in which one truthfully may say of me that I see a snake even though I take it to be a piece of rope. I elaborate on non-epistemic seeing and the contrasting notion of epistemic seeing in the next two sections.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that the analogy between Godfrey-Smith’s case and the inattentional blindness case is significantly weaker than advertised. While Godfrey-Smith– had he been oblivious to the presence of a cuttlefish– would have been surprised to learn that one was present, he would have reported seeing small rocks on the seabed. But subjects in the ‘gorilla’ experiments not only do not report seeing a gorilla, they do not report seeing anything big and black, anything thumping its chest, or anything moving across the scene. This is true, but the subjects in the experiments do report people moving about– some of whom are dressed in black. It is not implausible to suggest that the subjects’ visual systems treat the ‘gorilla’ as another person dressed in black. In assessing the plausibility of this suggestion, it is important to take into account the task subjects were given: to count the number of passes between players dressed in white. We can be confident that few resources would have been allocated to the processing of information about people in black.

There can fail to be sensory stimulation from x even though it is only partially occluded by y– if the rest of x is occluded by another object. In such as case, x is obviously not seen. But nor is there any reason to think the (partial) occlusion of x is seen.

Consider: x’s state of being occluded is, roughly, things being such that something blocks S’s view of x (wholly or in part). What is it to see this– i.e., things being such that something blocks one’s view of x– as opposed to seeing x itself? On the most natural construal, I think, it is to see that something blocks one’s view of x. There may be other options, however. Robert Audi suggests that seeing-to-be– e.g., ‘seeing a log to be smoldering’ (Audi, 2013, 10)– is distinct from seeing that something is thus and so. It is beyond the scope of this paper to explore Audi’s seeing-to-be. But notice that if this notion– unlike what I am about to suggest with respect to seeing-that– has critical potential vis-à-vis DC, then then so much the better for my attempt to build a case against DC.

An anonymous reviewer suggests that we do not use ‘seeing-that’ literally if we say that the motorist sees that the fuel tank is half-full, any more than if we say that we see that an argument is flawed, for example. I do not agree. ‘Seeing-that’ reports are always about more than a purely visual achievement. Seeing that p entails believing that p (indeed, knowing that p, or so many philosophers think; cf. footnote 21). Moreover, secondary seeing-that involves additional non-perceptual elements. For example, the motorist must know or believe certain things about the connection between the fuel gauge on the dashboard and the level of fuel in the tank to be able to see that the tank is half-full. However, some (but not all) uses imply a genuinely perceptual component. The fuel gauge example is a case in point. The motorist finds out about the state of the fuel tank by looking– not, it is true, at the tank itself, but at something whose function is to keep drivers updated about the level of fuel in the tank. By contrast, I can see that an argument is flawed with my eyes closed. In any case, I think that the fact that many philosophers seem to accept that secondary seeing-that is genuine seeing-that (cf. footnote 19) is sufficient reason to take this idea seriously.

In continuing with this example, I shall ignore distracting complications due to the peculiarities of underwater viewing. Readers can simply substitute a case involving perfect camouflage in more natural (for humans) viewing conditions, if they prefer.

Someone might object that in a case of perfect occlusion the occluded object is visually differentiated: the edges of the occluder demarcate the occluded object, setting it apart from the background. I do not have a knockdown argument against this suggestion, but it seems counterintuitive to me, and I do not think it would be palatable to all DC advocates. Consider that, in principle, any number of objects might be lined up in front of a perceiver in such a way that the first perfectly occludes the second, which perfectly occludes the third, and so on. Clearly, I differentiate the first object from its immediate surroundings. But the edges of that object also demarcate the second, third, and nth object. It seems odd to suggest that I visually differentiate all those invisible objects from their surroundings, too. What might visually differentiating x be, on such a view? It would hardly be the phenomenological notion of visual differentiation that Siegel (2006) puts forward, for the invisible second, third… and nth objects do not figure in the visual phenomenology at all. Nor can it mean to have certain sensory-motor dispositions (a proposal Siegel also considers; cf. 2006, 436 − 37) such as the disposition to take hold of the object, or trace its outline with one’s finger. For there is no reason to suppose the subject has any such disposition– she might not even know the second, third,… etc. objects are there. So what would visual differentiation be here? Note, in addition, that some friends of DC– e.g., Dretske (1969, 20) and Cassam (2007, 94, 105)– take visually discriminating x to be not only necessary, but also sufficient for seeing x. They, at any rate, could not accept the proposal under consideration. (I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for pressing the objection discussed in this footnote.)

In such a case, the measure of good eyesight would not be the ability to report the presence of an E, an R, and so on, but the ability to offer descriptions such as ‘There is a vertical line with three horizontal lines attached’.

As Siegel acknowledges, it is of course possible for a creature to see an object without being able to form demonstrative or de re thoughts about it. Otherwise, few non-human animals would be able to see things. The issue is whether, for creatures that are able to form de re thoughts, seeing an object entails being able to form such thoughts about it.

Dretske (2007) argues that this is possible. If so, this could be a clue to what is going on in cases of inattentional blindness: perhaps subjects see the ‘gorilla’, but fail to notice it.

The severely restricted scope of GOP2 helps reduce conceptual noise here. We know exactly what S is thinking about when she thinks about that which Cully now occludes: because Cully occludes Tully, all of Tully, and nothing but Tully.

This conclusion can be reinforced by scaling up the camouflaged object: if the latter takes up most of your visual field, it is very counterintuitive to suggest you literally see nothing there. (Thanks to an anonymous reviewer for pressing this point.)

For the longer story, see Stroll (1984, ch. 3).

I am not assuming that ‘S sees x’ entails ‘x reflects/absorbs/blocks/emits light’. Events– e.g. occlusion events– do none of those things, yet we can still see them. We can see them because they involve objects that do some of these things. And I am assuming– in line with philosophical orthodoxy– that objects must reflect/absorb (etc.) light in order to be seen.

I wish to thank past and present members of the ‘peer review’ working group at the Centre for Subjectivity Research, University of Copenhagen (Jelle Bruineberg, Bernhard Ritter, Ody Stone, and Julia Zaenker) for feedback on an early draft. I am also grateful to three anonymous reviewers– one for Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, and two for Synthese– for their many constructive and helpful criticisms and comments.

References

Audi, R. (2013). Moral Perception. Princeton University Press.

Austin, J. L. (1962). Sense and Sensibilia. Oxford University Press.

Briscoe, R. (2011). Mental Imagery and the varieties of Amodal Perception. Pacific Philosophical Quarterly, 92, 153–173.

Campbell, J. (2002). Reference and consciousness. Oxford University Press.

Cassam, Q. (2007). The possibility of knowledge. Clarendon.

Chisholm, R. M. (1957). Perceiving: A philosophical study. Cornell University Press.

Derksen, A. (2004). Occlusion shapes and sizes in a theory of depiction. British Journal of Aesthetics, 44, 319–341.

Dretske, F. (1969). Seeing and knowing. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Dretske, F. (2004). Change blindness. Philosophical Studies, 120, 1–18.

Dretske, F. (2007). What change blindness teaches about consciousness. Philosophical Perspectives, 21, 215–230. Philosophy of Mind.

Fish, W. (2009). Perception, Hallucination, and illusion. Oxford University Press.

French, C. (2018). Object seeing and spatial perception. In F. Dorsch, & F. Macpherson (Eds.), Phenomenal Presence (pp. 134–162). Oxford University Press.

Gibson, J. J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Gibson, J. J. (2002). [1972]). A theory of direct visual perception. Reprinted. In A. Noë, & E. Thompson (Eds.), Vision and mind: Selected readings in the philosophy of Perception. MIT Press.

Gibson, J. J., Kaplan, G. A., Reynolds, H. N., & Wheeler, K. (1969). The change from visible to Invisible: A study of optical transitions. Perception and Psychophysics, 5, 113–116.

Godfrey-Smith, P. (2016). Other minds: The Octopus and the evolution of Intelligent Life. William Collins.

Hansen, C. H., & Hansen, R. D. (1988). Finding the Face in the crowd: An anger superiority effect. Journal of Personal and Social Psychology, 54, 917–924.

Hyman, J. (1993). Vision, Causation, and occlusion. The Philosophical Quarterly, 43, 210–214.

Hyman, J. (2000). Pictorial art and visual experience. British Journal of Aesthetics, 40, 21–45.

Jackson, F. (1977). Perception: A Representative Theory. Cambridge University Press.

Johnston, M. (2011). On a neglected Epistemic Virtue. Philosophical Issues, 21, 165–218. The Epistemology of Perception.

Kahneman, D. (2012). Thinking, fast and slow. Penguin Books.

Kvart, I. (1993). Seeing that and seeing as. Noûs, 27, 279–302.

Mac Cumhaill, C. (2015). Perceiving Immaterial paths. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 90, 687–715.

Matthen, M. (2021). Objects, seeing, and object-seeing. Synthese, 198, 3265–3288.

McNeill, W. E. S. (2016). The visual role of objects’ facing surfaces. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 92, 411–431.

Nanay, B. (2010). Perception and imagination: Amodal Perception as Mental Imagery. Philosophical Studies, 150, 239–254.

Nanay, B. (2018). The importance of Amodal Completion in Everyday Perception. i-Perception, 9, 1–16.

Overgaard, S. (2022). Seeing-as, Seeing-o, and seeing-that. Philosophical Studies, 179, 2973–2992.

Overgaard, S. (2023). Backlighting and occlusion. Mind, 132, 63–83.

P Grice, H. (1961). The Causal Theory of Perception. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary 35, 121–152.

Pinkham, A. E., Griffin, M., Baron, R., Sasson, N. J., & Gur, R. C. (2010). The Face in the crowd effect: Anger superiority when using real faces and multiple identities. Emotion, 10, 141–146.

Pitson, A. E. (1984). Basic seeing. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 45, 121–129.

Pritchard, D. (2012). Epistemological disjunctivism. Oxford University Press.

Siegel, S. (2006). How does Visual Phenomenology Constrain Object-Seeing? Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 84, 429–441.

Simons, D. J., & Chabris, C. F. (1999). Gorillas in our midst: Sustained Inattentional blindness for dynamic events. Perception, 28, 1059–1074.

Sorensen, R. (2008). Seeing Dark things. Oxford University Press.

Sorensen, R. (2011). Two fields of Vision. Philosophical Issues, 21, 456–473. The Epistemology of Perception.

Stroll, A. (1984). Surfaces. University of Minnesota.

Travis, C. (2013). Perception: Essays after Frege. Oxford University Press.

Tye, M. (1982). A causal analysis of seeing. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 42, 311–325.

van Fraassen, B. C. (1980). The scientific image. Oxford University Press.

Warnock, G. J. (1965). Seeing. In R. J. Swartz (Ed.), Perceiving, sensing, and knowing (pp. 49–67). Anchor Books.

Williamson, T. (2000). Knowledge and its limits. Oxford University Press.

Funding

Open access funding provided by Copenhagen University

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

I declare that I have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Overgaard, S. Perceptual occlusion and the differentiation condition. Synthese 203, 128 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04574-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04574-3