Abstract

To date, research on bullying has largely employed empirical methodologies, including quantitative and qualitative approaches. Through this research we have come to understand bullying as both a dyadic and peer group phenomenon, primarily situated in the heads (thinking) of those involved, or in a lack of skill or expertise, or in the delinquency of a bully who needs to be reformed. This research has largely directed its strategies toward problem students using individual and peer group approaches. And yet school bullying continues to be a crucial educational issue affecting millions of students each year. In this project I introduce a missing philosophical perspective. Analyzing the work of Hans-Georg Gadamer I am led to conclude that typical anti-bullying strategies at times simply train bullies to be better at bullying (i.e., learning to bully more covertly, more expertly so as to inflict the same devastation without adult detection). Gadamer invites us to think about bullying in new ways. While certainly involving the thinking and skills of the bully and the victim, Gadamer contends that bullying does not fundamentally result from a problem within the participants, but is fostered by certain spaces between them; terrains that cultivate specific experiences of an "other". Generally, this project stems from an interest in the ways that domination develops in this "space between". Specifically in this paper I ask: What is the nature of "hermeneutic" experience as conceptualized by Gadamer? What kinds of experiences of an other does bullying exemplify? What kinds of experience of an other do non-bullying relations exemplify and what kinds of relational spaces foster such experience? This paper opens up significant new territory for anti-bullying work, expanding our focus to include the space between students which fosters certain inter-personal experiences - experiences situated in domination and stymied growth or, alternatively, experiences of reciprocity which open the possibility of human growth and transformation.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Bump is a recess game in which a long single-file line of participants forms facing a basketball hoop. The first person in line shoots from the free throw line. As soon as he or she shoots, the next person in line also tries to make a basket. If the person behind makes a basket first, the lead shooter is relegated to the sidelines. So it goes until one player is left, thus winning the bump game.

Up to this point these three boys had formed friendships with Matthew over the years. The four boys were involved in joint activities, had spent time in each other’s houses, etc. Jeff was popular, talented, from a demanding family with high expectations, and operated as the ringleader of this trio; Sammy, less popular, struggled with grades, came from a family that was both demanding and indulgent, and lived in Jake’s shadow; and Jeff, an only child, struggled academically, was sensitive, but masked that sensitivity, was from a permissive family, and desired to be Jake’s “right hand man.”

It is dyadic in the sense that it is seen as involving two problem individuals. It is a peer group phenomenon in the sense that peers are often present during the bullying encounter. Peer pressure is typically used as a deterrent to bullying, training peers to adequately stand up for the victim and to call for change in the bully.

From this perspective certain secondary questions arise. What deficiency in the bully leads to bullying? What lack in the victim leads to a propensity to be bullied? How can we better help the bully to understand the harm that bullying inflicts? How can we help the bully see life from the standpoint of the victim? How can we help the victim learn to be more assertive? What types of educational campaigns—slogans, clearly stated rules, and emphatically articulated consequences—will foster a change in both thinking and behavior? While, by necessity, many questions remain unexplored, these empirical findings are crucial to a holistic understanding of bullying. Certainly bullying contains dyadic, peer group, and individual aspects, elements which empirical research has carefully unearthed.

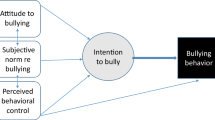

Though it is influenced by and situated within peer social structures (Salmivalli 1999), research primarily holds that bullying originates in the thinking, skill level, and actions of the bully. Largely, bullying is characterized by deficiency (e.g., lack of skill, understanding, or self-control within the bully; lack of skill, lack of friends/allies, or a lack of confidence in the victim). Anti-bullying strategies, stemming from these conclusions, have focused upon informational approaches (Hoover and Oliver 1996), skill building (Smith et al. 2001), empathy training (Horne et al. 2004), surveillance/reward/punishment (Perry et al. 2001), lecture (Olweus 1993), role playing (Hoover and Oliver 1996), gender narration (Simmons 2002), and school ecology (Espelage and Swearer 2004). Hence, based upon the current literature, bullying is primarily believed to be centered within the individual and strategies aimed at reducing it are focused upon fixing such individuals, whether through altering peer pressure upon bullies, or through increased surveillance and deliberate training.

This resistance to anti-bullying strategies is not an isolated phenomenon. While presenting a paper at an educational practitioner’s conference last year, I was approached by a Virginia school principal regarding the effectiveness of the anti-bullying programs in her school. While these programs were impacting some students, by and large the bullying she sought to eradicate continued. She was seeking to understand why bullying was resistant to the well-researched strategies employed within her school.

According to Boiven, Hymel, and Hodges approximately 10% of all elementary and middle school students are "repeatedly harassed and victimized by schoolmates” (2001, 266). Craig, Pepler, Connolly, and Henderson, doing similar research in Canada, contend that 20% of similar-aged students there report being victimized (2001). However, when students were asked if they had ever been bullied in their school years, Hoover et al. found that 81% of males and 72% of females had, indeed, experienced bullying in one form or another (Holt and Keys 2004). Further, bullying is deeply harmful to both the victim and the bully. Victims of bullying struggle with "depression, anxiety, emotional disregulation, social withdrawal, low self-esteem, loneliness, suicidal tendencies, dislike and avoidance of school, poor academic performance, rejection by mainstream peers” (Perry et al. 2001, 73) and are "more aggressive, more withdrawn, less sociable, and/or less cognitively skilled than their more accepted peers” (Boivin et al. 2001, 268). Regarding the bully, research by Olweus finds that, "Approximately 60 percent of boys who were characterized as bullies in grades 6–9 had at least one [criminal] conviction by the age of 24 (1993, 36). Olweus continues, "Even more dramatically, as much as 35–40 percent of the former bullies had three or more convictions by this age, while this was true of only 10 percent of the control [i.e., non-bullying] boys” (Olweus 1993, 36). Atlas and Pepler contend that their research, examining the continuity between adolescent and adult bullying, “revealed that bullying at age 14 predicts bullying at age 32” (1998, 93). In addition, bullying not only encompasses the lives of the bully and the victim, but the larger school population as well. The story of Jake and Matthew is typical. Jake recruited accomplices, then a larger group of peers who participated in the bullying of Matthew. The bullying phenomenon incorporates bullies, victims, accomplices, bystanders, and defenders; thus often recruiting a large population of a school into active involvement in the bullying scenario. Research indicates that over 70% of the school population is involved in any given bullying situation in one form of another (Salmivalli et al. 1996). Finally, in the wake of the school shootings of late, Espelage and Swearer claim that “71% [of the shooters] had been the target of a bully” (2003, 367).

It is important to add, as Patricia Altenbernd Johnson points out, that “this does not mean that the scientific approach is not important for contemporary humanity. But, [that] scientific objectivity is not able to provide the fullest insight into human existence” (2000, 49).

Reactive aggression is aggression that is expressed when provoked by another (Schwartz et al. 2001, 164).

“i.e., he confronts [him] in a free and uninvolved way—and by methodically excluding everything subjective, he discovers what [the victim] contains. [In essence] he thereby detaches himself from the continuing effect of the tradition in which he himself [the bully] has his historical reality” (Gadamer 1996, 358–359).

It is important, here, to interject a caveat. Without prejudice toward, or if we have no tradition constituted historically with that which we confront, understanding eludes us. But, as prejudices open us to future understanding, they can also work in reverse. In our discussion of predictively experiencing another we see another instance of prejudice. Jake knew Matthew. In this posture of knowing, Jake did not allow Matthew to address him. Prejudice in this case actually shuts down future experience or understanding. Hence, while tradition positions us toward the possibility of future understanding—without such prejudice understanding becomes impossible—yet, if our experience or understanding with another is not hermeneutic in nature (as outlined earlier) prejudice, then, comes to work as a barrier to future experience or understanding.

By subject matter Gadamer means anything that could be considered between two people (e.g., a school subject, the nature of status, a political reality, etc.).

Research by Long & Pellegrini 2003 underscores the fact that the bullying relationship often rests in an attempt to secure privilege or status. Drawing on the literature on social dominance, they assert that in bullying “individuals compete with each other using both aggressive and affiliative strategies to gain status” (2003, 402). “Bullying,” they contend, “is viewed as an agonistic strategy used to obtain and maintain dominance (Bjorklund and Pellegrini 2002). There is evidence that bullying is a successful strategy for attaining and maintaining dominance as individuals who get the better of their peers are often leaders of peer cliques and are found to be more attractive to the opposite sex (Pellegrini and Bartini 2001; Long and Pellegrini 2003; Prinstein and Cohen 2001; Sutton et al. 1999). Further, dominant individuals use affiliative strategies, such as reconciliation and alliance building, after status has been exhibited (Pellegrini and Bartini 2001; Strayer, 1980)” (2003, 402). Here, then, the question of bullying is linked with subjects of status, privilege, and identity. Gadamer would suggest that creating tentativeness around these subjects provides an opportunity for address, self-understanding, and growth.

Although, I would argue that such certainty often covers over important questions regarding assumptions and the limits of current scientific understanding.

Indeed, some studies indicate that bullies score lower on “perspective taking” than non-bullies (Farley 1999), but this continues to be a contested finding within the bullying literature (Espelage and Swearer 2003). Empathy training does seem to bring modest change in some circumstances, while in others it remains largely ineffective.

Through coercion, surveillance, skill building, and informational anti-bullying approaches—especially if we do not carefully consider the terrain in which bullying develops—the bully learns to be more covert, at times bullying under the watchful eye of a nearby teacher. He has become more skilled at bullying. We have failed to create a space in which bullying itself—as an answer to a question—becomes questionable.

References

Atlas, R. S., & Pepler, D. (1998). Observations of bullying in the classroom. The Journal of Educational Research, 92, 86–99.

Bjorklund, D. F., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2002). The origins of human nature: Evolutionary developmental psychology. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

Boivin, M., Hymel, S., & Hodges, E. V. E. (2001). Toward a process view of peer rejection and harassment. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: The Guilford Press.

Burkowski, W. M., Sippola, L. K. (2001), Groups, individuals, and victimization: A view of the peer system. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Craig, W. M., Pepler, D., Connolly, J., Henderson, K. (2001). Developmental context of peer harassment in early adolescence: The role of puberty and the peer group. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York: The Guilford Press.

Egan, S. K., & Perry, D. (1998) Does low self-regard invite victimization? Developmental Psychology, 34, 299–309.

Espelage, D. L., & Swearer, S. M. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32, 365–383.

Espelage, D. L., Swearer, S. M. (Eds.), (2004). Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Farley, R. L. (1999). Does a relationship exist between social perception, social intelligence and empathy for students with a tendency to be a bully, victim or bully/victim? Honours thesis. Adelaide: Psychology Department, University of Adelaide.

Gadamer, Hans-Georg (1996 (1975, 1960)). Truth and method. New York: Continuum.

Habermas, J. (1977). A review of Gadamer’s truth and method. In F. R. Dallmayr & T. A. McCarthy (Eds.), Understanding and social inquiry. Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press.

Holt, M. K., & Keyes, M. A. (2004). Teachers’ attitudes toward bullying. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention. Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Publishers.

Hoover, J. H. & Oliver, R. O. (1996). The bullying prevention handbook. National Education Service, Bloomington IN.

Horne, A. M., Orpinas, P., Newman-Carlson, D., & Bartolomucci, C. L. (2004). Elementary school Bully Busters program: Understanding why children bully and what to do about it. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American school: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention. Mahway NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

Johnson, P. A. (2000). On Gadamer. Wadsworth, Australia.

Long, J. D., & Pellegrini, A. D. (2003). Studying change in dominance and bullying with linear mixed models. School Psychology Review 32, 401–417

Misgeld, D., Nicholson, G. (Eds.), (1992). Hans-Georg Gadamer on education, poetry, and history. Translated by Schmidt, Lawrence & Reuss, Monica. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at School. Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (2001) Peer harassment: A critical analysis and some important issues. In M. Juvonen, K. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Pellegrini, A. D., & Bartini, M. (2001). Dominance in early adolescent boys: Affiliative and aggressive dimensions and possible functions. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 47, 142–163.

Perry, D. G. Hodges, E. V. E., & Egan S. K. (2001). Determinants of chronic victimization by peers: A review and a new model of family influence. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Prinstein, M. J., & Cohen, G. L. (2001, April). Adolescent peer crowd affiliation and overt, relational, and social aggression: Using aggression to protect one's peer status. Paper presented at the biennial meeting of the society for research in child development, Minneapolis, MN.

Rigby, K. (2001). Health consequences of bullying and its prevention in schools. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Salmivalli, C. (1999). Participant role approach to school bullying: Implications for interventions. Journal of Adolescence 22, 453–459

Salmivalli, C. (2001). Group view on victimization: Empirical findings and their implications. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized. New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Salmivalli, C., Lagerspetz, K., Bjuorkqvist, K., Osterman, K., & Kaukiainen, A. (1996). Bullying as a group process: Participant roles and their relations to social status within the group. Aggressive Behavior, 22, 1–15

Schwartz, D., Proctor, L. J., & Chien, D. H. (2001). The aggressive victim of bullying: Emotional and behavioral disregulation as a pathway to victimization by peers. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 49–72). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Simmons, R. (2002). Odd girl out: The hidden culture of aggression in girls. New York: Harcourt

Smith, P. K., Shu, S., & Madsen, K. (2001). Characteristics of victims of school bullying: Developmental changes in coping strategies and skills. In J. Juvonen & S. Graham (Eds.), Peer harassment in school: The plight of the vulnerable and victimized (pp. 49–72). New York, NY: The Guilford Press.

Strayer, F. F. (1980). Social ecology of the preschool peer group. In W. A. Collins (Ed.), The Minnesota symposia on child psychology. Development of cognition, affect, and social relations (Vol. 13, pp. 165–196). Hilisdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Socially undesirable need not be incompetent: A response to Crick and Dodge. Social Development, 8, 132–134.

Weinsheimer, J., Marshall, D. (1996 (1975, 1960)). In Gadamer, Hans-George Truth and Method, translators’ preface. New York: Continuum

Whitaker, D., Rosenbluth, B., Valle, L. A., & Sanchez, E. (2004). Expect respect: A school-based intervention to promote awareness and effective responses to bullying and sexual harassment. In D. L. Espelage & S. M. Swearer (Eds.), Bullying in American schools: A social-ecological perspective on prevention and intervention. Publishers Mahway, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Jacobson, R.B. A lost horizon: the experience of an other and school bullying. Stud Philos Educ 26, 297–317 (2007). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-007-9026-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11217-007-9026-6