Abstract

The “traditional view” on the historical decline of child labour has emphasised the role of the approval of effective child labour (minimum working age) laws. Since then, the importance of alternative key driving factors such as schooling, demography, household income or technology has been highlighted. While historically leading countries such as England and industrial labour have been studied, peripheral Europe and a full participation rate also including agriculture and services have received limited research attention. The contribution of this paper is to provide a first empirical explanation for the child labour decline observed in a European peripheral country like Portugal using long historical yearly data. For doing so, we use long series of Portugal’s child labour participation rate and several candidate explanatory factors. We implement cointegration techniques to relate child labour with its main drivers. We find that not only factors related to the “traditional view” were important for the Portuguese case. In fact, a mixture of legislation, schooling, demography, income, and technological factors seem to have contributed to the sustainable fall of Portugal’s child labour. Hence, explanations for observed child labour decline seem to differ by country and context, introducing a more nuanced view of the existing literature.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

The decline of child labour observed in many countries represented a major change in societies, with its strong impact on the economy and on the lives of children. However, the determinants of the decline of child labour remain a matter of debate. According to Cunningham and Viazzo (1996) till the early 1970s, the “traditional view” on the history of child labour remained undisputed. According to this view, the Industrial Revolution led to an unprecedented use of child labour and children were rescued from their situation by activists and most importantly by the passage of effective child labour (minimum working age) laws (Hammond & Hammond, 1917; Hutchins & Harrison, 1926).Footnote 1 The “traditional view”, which focuses mainly on industrial child labour, argues that while children did work before industrialization such work was not exploitative. Furthermore, it gives primacy to a legislative approach driven by socially aware campaigners in reducing child labour.

In the late 1980s and early 1990s, a series of studies (Goldin, 1979; Bolin-Hort, 1989; Nardinelli, 1990; Horrel & Humphries, 1995a, b) challenged this traditional view. These papers argued that child labour was already widespread in non-industrial settings and may have taken place under more harmful conditions than during the Industrial Revolution. Since minimum working age laws were applicable essentially to industrial employment, it is unlikely that the bulk of working children came under the ambit of such laws. Hence, it is also unlikely that the widespread disappearance of child labour may be attributed exclusively to labour laws. These papers thus offer an alternative assessment of the factors driving the historical decline of child labour in currently developed countries.

Studying the literature, five main drivers of decline, namely labour legislation, schooling, demography, household income and technology, may be identified. Broadly, child labour legislation frames the practice and is important in terms of promoting or censoring the practice of children working. Availability (and quality) of schooling is conjectured to be inversely related to child labour practice and an increase in schooling is expected to translate into reductions in child labour, holding other factors fixed. Demography, fertility, and the share of children in the population change the child role in society by regulating the labour supply of children which in turn influences child labour practice. Lack of income forces families to send children to work, and once a certain income level is reached child labour may be expected to decline. The level and type of technology constrain the production system and eventually the contribution of children. Most advocates of each driver do not suggest that there is a mono-causal relationship but highlight one of the factors listed above as the key force driving child labour.

On the other hand, the historical literature focused on leading countries such as England (Humphries, 2003; Nardinelli, 1980) or the U.S. (Moehling, 1999; Puerta, 2010), but acknowledged the diversity of historical trajectories of child labour. For example, Humphries (2003) compares the evolution of child labour across different levels of GDP per capita and suggests that child labour rates in industrializing Britain were higher than in any other first industrializers or today’s developing economies and that Britain presented child labour decline at comparatively higher GDP per capita levels than other historical or contemporary cases. Moreover, most of the literature uses industrial surveys or census that only provide a partial picture of this phenomenon and does not allow for identifying the precise moments and shape of the decline.

In addition, given that the literature mainly focuses on specific industries (Nardinelli, 1980; Puerta, 2010) or, in general, industrial labour (Humphries, 2003; Moehling, 1999), there is far less knowledge about the reduction of child labour in the agricultural and service sectors. This primary focus on industry also implied that child labour analyses with a historical and empirical perspective are mostly limited to historically leading economies, neglecting the peculiarities of the periphery, and of late industrializers. By not accounting for the overall variation of child labour across sectors or in peripheral countries, the state of the art thus allows only for a partial understanding of the observed child labour decline.

This paper contributes to the literature with a first empirical assessment of the historical drivers of the child labour decline in a European peripheral country like Portugal throughout the twentieth century. We rely on Goulart and Bedi (2017) to obtain yearly estimates for the percentage of child workers during a substantial part of the twentieth century and illustrate the historical decline of child labour in this country. We then build a dataset with several candidate explanatory variables representing legislation, schooling, demography, income, and technology factors. Considering the features of this set of time series, we implement different cointegrating regression techniques and model specifications to estimate the impact and relevance of each main driver on Portugal’s child labour and check the robustness of the results. Our empirical strategy includes well-known methods for cointegrating regression models such as canonical cointegrating regressions (CCR) and fully modified ordinary least squares (FM-OLS) which account for the potential endogeneity of the cointegrating regressors and serial correlation with a non-parametric approach, and dynamic ordinary least squares (DOLS) that augments the static regression with first differences of the cointegrating regressors and corresponding leads and lags.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to implement cointegration techniques applied to long-term child labour series and its corresponding candidate drivers.

Our results provide empirical evidence on the role played by different factors for the decline of child labour in Portugal, some in common with certain first industrializers, while others highlighting the peculiarity of peripheral experiences. Particularly, we find that both minimum age and compulsory schooling laws contributed less than other dimensions to the decrease of the participation rate of children in labour. Alternatively, it seems that the increase in school enrolment and school quality, and the changing role of women in the labour market had a strong and robust long-run contribution to the historical decline of child labour. Furthermore, our results suggest that rising income levels and technological progress, by enhancing productivity in agriculture and industry, also played a significant role in reducing the need for children to work, curbing child labour levels in Portugal.

2 Historical Analyses of Child Labour: A Review

2.1 Labour Legislation and Activism

The traditional argument for the observed child labour decline is that labour laws have been the key instrument through which child labour has been reduced. Laws setting the minimum working age at 12 were successively introduced in Europe and the United States between 1830 and 1910 with the support of progressive elites or organised male adult labour.Footnote 2 These laws, which set the threshold(s) between childhood and children, and adults (Hindman, 2009b), were introduced on the back of a discourse, first articulated in Britain in the 1830s, that children should have a right not to work. According to Cunningham (2001), this notion was “truly revolutionary” as till then it had been assumed that it was the role of the State and parents to find work for their children. Critics have pointed out that a legal approach banning child labour may not be supported by those whom they purport to help and may indeed push children into worse forms of labour. Indeed, such laws may be used as protectionist devices to promote the interests of organized labour and, in an international context, to protect industries rather than being driven by concerns about child labour (Basu, 1999).

There is credible evidence that a legal approach is effective in some instances, as in the case of the 1833 Factory Act in Britain, which led to a reduction in the use of children in the industry (Cunningham & Viazzo, 1996). However, the argument that legislation has been the key determinant is disputed. First, such laws have most often centred on formal industrial work, while ignoring non-industrial work and the informal sector, where the bulk of child labour was located. Second, most laws were implemented when child labour was already declining, as in England, France, and the United States, or already at a low level, as in Japan (Brown et al., 1992; Hindman, 2009b; Heywood, 2009). Third, econometric analysis has not always found evidence of a causal relationship between minimum working age laws and child labour. For example, in the context of the late nineteenth Century and the beginning of the twentieth century, Moehling (1999) found no evidence that changes in minimum working age laws focused on industry exerted a statistically significant effect on the decline in child labour during this period across the United States. This is also confirmed by the experience of today’s developing economies, where child labour laws seem to explain little of the variation in paid employment of children across countries (Edmonds & Shrestha, 2012).

However, the key issue regarding legislation may not be the adoption of minimum age employment laws per se, but its enforcement. The criticism is that using the existence of legislation to examine the effect of laws on child labour is not adequate has been pointed out by other researchers as well. For instance, researchers who have used legislation approval in the past have often been criticized for holding a ‘narrow view’ of legislation (Huberman & Meissner, 2010; Moehling, 1999). Most importantly, laws initially often only covered industrial labour leaving the rural sector, where child labour was prevalent, unregulated or, at best, unmonitored (see, for instance, Effland, 2005). In the case of Portugal, and more generally, for historical research, the practical possibility of assessing law enforcement was often limited. While acknowledging that passage of legislation and enforcement are clearly two different issues, there is little that can be done in the current case, and hence the focus here is on the passage of legislation. To the extent that change in political rhetoric is a measure of willingness to enforce laws, in the Portuguese case, in the 1930s and 1940s the rhetoric emphasized the importance of labour while, by 1989, after substantial declines in child labour, it changed in favour of castigating the work of children (Eaton & Goulart, 2009). Others have also emphasized the influence of cultural beliefs on the roles of women and children in societies, which may change slower than laws (Cunningham, 2000).

2.2 Schooling

Compulsory schooling laws have also been pointed out as important measures to attenuate the child labour problem. For example, based on a study of child labour in India, Weiner (1991) argues that a firmly enforced policy of compulsory schooling can attenuate substantially child labour. It has been argued that schooling laws are easier to enforce than labour laws as education inspectors are less easily bribed by parents than labour inspectors are by employers (Fyfe, 2009).

Implementation of schooling laws and an increase in the availability of schooling have been suggested by several analysts and international organizations to be the key to eliminating child labour. For example, ILO (1998) argues that “the single most effective way to stem the flow of school-age children into abusive forms of employment is to extend and improve schooling so that it will attract and retain them”. The basic argument is that schooling competes with economic activity in the use of children’s time. Therefore, policy interventions such as improvements in access to schools, and/or improvements in the quality of schools, may raise school enrolment at the expense of child labour.

The idea is that work and schooling are perfect substitutes. In addition to the obvious concern that implementing compulsory schooling laws without an adequate supply of worthwhile schooling is meaningless, there is substantial evidence that children can combine work and schooling.Footnote 3 In this sense, a number of papers (Hazarika & Bedi, 2003; Ravallion & Wodon, 2000) have shown that educational policies are effective in terms of increasing school enrolment, but this does not translate into an equivalent reduction in time spent in the labour market. Recent micro-evidence from today’s developing economies also highlights that this issue may vary across types of work, genders and between rural/urban areas, suggesting that the socio-economic context matters for child-time allocation decisions between schooling and work (Dayioglu & Kırdar, 2020; DeGraff et al., 2016).

2.3 Demography

An old hypothesis which has regained prominence has been the fertility-child labour nexus. The basic argument is that demographic patterns regulate the abundance of children in societies and therefore their relative worth and decisions regarding the allocation of their time. Two strands of literature have arisen. One strand argues that households have more children as they are seen as a source of income and labour. Fertility decisions are partly based on the needs and the opportunities that households must send children to work. In this setup, the spread of female education and greater labour market opportunities for women increase the shadow price of their time (Becker, 1992; Mincer, 1962; Rosenzweig & Evenson, 1977), and increase the opportunity cost of children (Galor & Weil, 1996). Households react to the changes in incentives by reducing the number of children and investing more heavily in the quality of children.

Who is working within the household may also accelerate or delay this demographic transition. Horrell and Humphries (1995a) refer that the opportunity cost of working for mothers and children influences this dynamic. Once female wages increase relative to children or the institutional impediments regarding female work participation are resolved, adult female labour force participation may be more attractive, and child work can be substituted by time dedicated to school.Footnote 4 Horrell and Humphries (1995b) suggest that the male-breadwinner family may have further prolonged children’s work as women faced institutional and ideological obstacles in the labour market.

The second strand argues that “children work because people have children, rather than people have children because children work” (Dyson, 1991). In a context of limited contraceptive availability and high mortality, household control over fertility is reduced. Instead, the proposed explanation is that eventually, death and infant mortality rates decline through better nutrition and the spread of basic hygiene and medical treatment. Declining death rates create population pressure at the household level until fertility declines, and in turn, the decline in fertility translates into a decline in child labour. A balance of the evidence suggests both strands are somewhat unconvincing (Vlassof, 1991; White, 1982) and more recent work has stressed that fertility and child labour decisions interact instead of a one-way causal relationship (Emerson, 2009).

While much of the literature has a micro-focus, several papers (Dessy, 2001; Galor & Weil, 2000; Hazan & Berdugo, 2002; Strulik, 2004) have adopted a macro approach to examine the relationship between fertility and child labour.Footnote 5 For example, Galor and Weil (2000) look at the history of the Western world and illustrate how the demographic transition is fundamental for the change from a (post-Malthusian) regime, where both output and population growth rates are high, to a (modern growth) regime, where population growth rates have decreased. In this modern-growth regime, it is possible to shift from an emphasis on quantity to the quality of children. Recent evidence with a micro-focus from the history of first industrial countries such as the USA seems to support this argument (Shanan, 2023). At the same time, Strulik’s (2004) two equilibria model motivated by today’s developing countries suggests that parents shift to child quality at a per capita income of $450 when income and mortality have reached acceptable levels. At $1,000, child mortality reaches a trough and is almost constant, while fertility continues to decrease and so does child labour.

2.4 Household Income and Wages

The income hypothesis suggests that children work because households are poor and the optimal household strategy to sustain household welfare at a given point in time is to rely on child labour. Once income starts increasing, the family will phase out child labour (Nardinelli, 1990) and substitute schooling in place of work. This has been suggested in the context of the historical European decline of child labour by Fallon and Tzannatos (1998). They found that the percentage of child workers decreased rapidly in countries with per capita GDP of $500 or more. More recent evidence from Vietnam (Edmonds, 2003), Brazil (de Carvalho Filho, 2012) and Turkey (Dayioğlu, 2006), among others, corroborates this reasoning.

However, this relatively intuitive argument has been questioned.Footnote 6 It has been pointed out that the increase in the real earnings of adults may not lead to declines in child labour. An increase in family income and wages may be accompanied by an increase in demand for goods and services which in turn may call for more child labour. This dynamic seems corroborated by Kambhampati and Rajan (2006), who find that, in the context of India, economic growth risks increasing (instead of decreasing) child labour in the short run because it puts pressure on the demand for child workers. Furthermore, an increase in wages may not lead to a substitution of child work by schooling as parents may not recognize education as a useful investment (Cunningham & Viazzo, 1996; Krauss, 2017). Evidence with a micro-focus on this argument reflects to a certain extent the so-called “wealth paradox” which implies that, in certain settings, child farm labour may also emerge from the wealthiest families (Bhalotra & Heady, 2003). Nevertheless, despite all these valid arguments, in the context of long-term economic changes, the main bulk of evidence in the literature seems to suggest child labour is likely to be more responsive to increasing living standards and adult wages than child wages (Edmonds & Theoharides, 2020).

2.5 Technology

Economists and historians have stressed the role of technology in the evolution of child labour. Broadly, technological advancements increase skills requirements to work and exclude children from the labour market, given they do not possess the necessary skills to manipulate such technologies. By doing so, technological changes also boost the marginal productivity of adult workers, raising their wages and employment and reducing the need for child labour in the economy (Basu and Van, 1998). However, the literature suggests two key issues regarding this driver. The first is the potential difference between the immediate and long-run effect of technology, and the second is that the effect of technology is not unambiguous and is likely to depend on the type of technology under consideration.

During the initial period of industrialisation, changes in technology may have led to an increase in child labour. This may have worked through several channels. A direct channel is that “skill-saving” technical innovations may reduce the importance of strength and skill and provide a greater incentive for the engagement of women and children.Footnote 7 For example, in the case of textiles, labour-intensive technology with children in an auxiliary role made children’s nimble fingers and small body size an advantage. In this context, children were ideal as cheap and docile labour and, because of increased demand, child relative wages increased in the English textile industry between 1830 and 1860 (Tuttle, 2009). On the other hand, it is still unclear whether children have an absolute advantage within certain production settings and there is scant empirical support for the “nimble fingers” argument in today’s developing economies, where findings seem to suggest children are generally less productive than adults (Edmonds, 2007).

However, there can be also indirect channels. Based on an analysis of industrialization in Catalonia between 1850 and 1920, Camps (1996) points out that in the textile industry, mechanization led to a movement away from home production to industrialized production and involved a reduction in the labour force participation of married women and greater use of children and young adults. Additionally, traditional crafts and home industries may increase the use of children to compete with mechanization in modernizing agriculture and industry. Based on an analysis of the textile industry in Ghent between 1800 and 1914, De Herdt (2011) argues that to compete against ever-lower prices driven by industrial developments, home workers began working longer hours and called for greater work participation from their children.

Although there may have been cases where an increase in child labour was recorded following the initial introduction of mechanization, most of the literature suggests that a sustained spread of technological innovations translates into a decline in child labour in the long run. This is through its effect on increased agricultural and industrial production which implies greater human capital requirements (Schultz, 1964). For example, Reis (2004) based on a census of Lisbon’s industries reports evidence of capital-skill complementarity by 1890.

Given the magnitude of child labour in agriculture across history (see, for instance, Humphries, 2003), increased agricultural productivity related to skill-biased technological changes can imply a peculiar pivotal role in reducing child labour in the overall economy. For instance, Rosenzweig (1981) reports that the green revolution in India was associated with a reduction in child labour and an increase in school enrolment. Levy (1985) shows that the mechanization of Egyptian agriculture, especially the use of tractors and irrigation pumps reduced the demand for child labour in some specific tasks. The effect of mechanization and irrigation on child labour seems also confirmed by more recent micro-evidence from Africa and Asia, such as Admassie and Bedi (2008), Webbink et al. (2012) and Takeshima and Vos (2022). On the other hand, the impact of land-saving technologies on child labour, such as fertilizers and improved seeds, has been found to be ambiguous, and, in the short run, the use of such technologies has been associated with an increase in the work burden of children (Admassie & Bedi, 2008).

3 Data and Variables

This section describes the dataset used in this study to represent child labour and the corresponding driving factors related to legislation, schooling, demography, household income and technology.

3.1 The Portuguese Child Labour Series

As for the child labour data, we build mainly on Goulart and Bedi (2017) to obtain yearly estimates for the participation rate of children from 10 to 14 years old in the labour force between 1937 and 1994 based on pooling 14 labour surveys implemented by the Portuguese National Institute of Statistics (Instituto Nacional de Estatística, INE) per trimester between 2001 and mid-2004. Our original sample contained information on 1,424,012 individuals, further reduced to 1,059,084 due to excluded situations in the first employment declared by the respondents.Footnote 8 In our estimates, we exploit responses in these surveys to the retrospective question “When did you start working for the first time?” extrapolating age participation groups and deriving a continuous series of patterns of child labour through 57 years. To achieve this, we calculate the ratio of individuals in the age group 10–14 years old who are working to the overall number of respondents within the corresponding age bracket in a given year.Footnote 9

In this context, we select the age group 10–14 years old because it aligns with conventional census age groups used in historical data collections, ensuring temporal comparability with other country-level estimates found in the literature (see, for instance, Nardinelli, 1980; Toniolo & Vecchi, 2007). Secondly, this age group is included to align with the national minimum working age standards (1891: 12-year-old; 1969: 14-year-old), thereby ensuring consistency in the series. Thus, in the article, we opted for keeping a fixed age-based approach with the upper limit as 14 years old, excluding work carried out by children between 15 and 17 years old, which would remain broadly outside the scope of child labour legislation for the period under analysis.Footnote 10 Furthermore, the nature of the question we exploited refers to general first work experiences. In relation to this, we use the term "child labour" broadly to encompass all reported work activities of respondents. Hence, our intention is not to tie this term to harmful or harmless outcomes, but to track key historical changes in children's work participation in Portugal.

We also must acknowledge the use of retrospective information for estimating child labour series is open to questions as this approach is susceptible to recall biases from respondents, particularly in older cohorts. These inaccuracies in reporting life-course events are influenced by major factors, such as the complexity of employment history, sociodemographic characteristics of individuals, the length of the period asked to recall, and the salience and significance of the life-course event into consideration (Shattuck & Rendall, 2017). For instance, asking respondents about significant employment-related events like first employment has been shown to mitigate recall biases in the scholarly literature (Steijn et al., 2006). In contrast, the recall of unemployment status may be more susceptible to this issue (Kyyrä & Wilke, 2014). Although it is impossible to test the accuracy of the data in use, the INE surveys used in this article specifically request information about the first work activity. Consequently, we assume that the reliability of our data aligns well with standards observed in other retrospective employment status information within the existing literature.

3.2 Other Dimensions of Child Labour

We proceed to describe the variables selected to represent the legislation, education, demographics, income and technology dimensions and justify their use to characterize the dynamics of child labour.

We use the minimum start working age (min_age) and the number of compulsory schooling years (school_years) as variables representing the legislative dimension. The approval of laws that increase the minimum start working age sets a legal framework under which child labour is forbidden. According to the “traditional view”, such legal restrictions were decisive for the historical decline of child labour, but several arguments dispute this claim as explained in Sect. 2.1. The change in the number of compulsory schooling years is another legal measure which has been pointed out as important to reduce child labour.

We use the primary enrolment (enrol) and the student–teacher ratio in primary school (ratio_pt_prim) to represent educational factors. These variables may be seen as proxies for school enrolment or availability, and school quality related to class size, respectively.Footnote 11 As explained in Sect. 2.2, if working time and schooling act as substitutes in these group ages, improvements in the schooling factor may contribute to decrease child labour. However, the link between education and child labour may be weak if children easily combine schooling and work and we contribute empirically to this discussion.

We use % of children in the total population (ch_pop) and the infant mortality per thousand births (inf_mort) as variables capturing demographic and fertility patterns. Both proxy the societal transition where parents do not see children as a source of income and labour anymore and shift towards investment in child quality as highlighted in Sect. 2.3. We also complement the demographic factors with the male–female wage ratio (ratio_mf_wage). As relative female wages increase, adult female participation becomes more attractive, and this lowers the incentives for child work within the household.

We set real GDP per capita (gdp_pc), labourer’s wage (wage) and government social expenditure as % of GDP (gov_social_exp) as variables describing the income effect over child labour. The income hypothesis suggests that households phase out child labour and remove their children from work as a result of the increase in their income, although there are cases where this relationship may be questioned as discussed in Sect. 2.4. GDP per capita and wage both try to capture the evolution of income throughout the period under analysis. The government social expenditure as % of GDP can be seen as a complementary measurement for the income effect as it may represent more direct policies to tackle the poverty of families. Lower-income households are the ones that are more likely to send their children to some kind of work. Hence, child labour may tend to decrease if these families are more financially supported.

Finally, we choose land productivity of wheat (land_prod_wheat), land productivity of maize (land_prod_maize), and the value added per industrial worker (value_added_pw) as variables representing the technological factor. Traditionally, child labour has been a tale of agricultural and industrial work as explained in Sect. 2.5 and, therefore, these variables try to measure the changes in the technology used for production through the introduction of new innovative machinery on these two sectors and its impact on the agricultural and industrial productivity.

The result of this compilation is a dataset composed by 12 variables for 57 years. A detailed account of the variables is provided by Table 1 with reference to the data source and the sample period with available information.

4 Analytical Framework

To study if and how factors related to legislation, schooling, demography, income, and technology have contributed to the steady decrease in Portugal’s child labour rate, we use the multivariate dataset described in Sect. 3.

The econometric model used to describe the main determinants of the child labour rate, \(child\_labour\), under the most general framework, may be represented as:

where \({\beta }_{L}, {\beta }_{S}, {\beta }_{D}, {\beta }_{I}\:\text{and}\:{\beta }_{T}\) are vectors of unknown coefficients which characterize the direction and magnitude of the long-run effects of the legislation (\(La{w}_{t})\), schooling \((Schoo{l}_{t})\), demographics (\(Demo{g}_{t})\), income (\(In{c}_{t})\) and technology (\(Tec{h}_{t})\) variables on Portugal’s child labour rate (\({child\_labour}_{t})\) and \({u}_{t}\) is the error term which includes other factors that may affect child labour in this context. As explained below, depending on the chosen specification \(La{w}_{t}\), \(Schoo{l}_{t}\), \(Demo{g}_{t}\), \(In{c}_{t}\), and \(Tec{h}_{t}\) may either be scalars or vectors if they include one or more of the variables from each dimension. Equation (1) is a linear regression model with time series variables and it turns out to be a cointegrating regression if all variables are I(1) and \({u}_{t}\) follows a stationary and weakly dependent process (abbreviated as I(0)). We will confirm these features on Sects. 5.1 and 5.2.

If \({u}_{t}\) is I(0) such that the variables included in Eq. (1) are cointegrated, the final step is to obtain reliable estimators for the slope coefficients and test statistics with standard properties. Assuming that the time series included in the econometric model are I(1) and cointegrated, a first idea would be to estimate Eq. (1) by Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) but it has been shown that, if serial correlation is present and regressors are endogenous, \({\widehat{\beta }}_{OLS}\) may have non-standard asymptotic distributions and second-order bias which affects its performance in finite samples (Banerjee, et al., 1986).

The literature proposed two ways to deal with these second-order bias effects: (1) a non-parametric approach which estimates Eq. (1) by OLS and then modifies \(\widehat{\beta }\) with appropriate non-parametric estimates of the nuisance parameters of the asymptotic distribution which are resultant of the serial correlation and endogeneity. The authors that proposed methods with this approach proved that the asymptotic second-order bias is cleaned from the asymptotic distribution of \(\widehat{\beta }\). The most popular methods which use non-parametric corrections on \(\widehat{\beta }\) are the Fully-Modified OLS (FM-OLS) (Phillips & Hansen, 1990) and the Canonical Cointegrating Regression (CCR) (Park, 1992). (2) a parametric approach which adds a dynamic specification to the initial model to take account of the serial correlation and endogeneity of the regressors. One of the most popular estimators in this class is the Dynamic OLS (DOLS) which augments Eq. (1) with the first differences of the regressors and corresponding leads and lags and then estimates the resulting regression by OLS. It also has been shown that this approach effectively corrects for the presence of second-order bias effects (Saikkonen, 1991).

Despite some comparative studies (for example Montalvo, 1995; Capuccio and Lubian, 2001; and Christou & Pittis, 2002), to our knowledge, none of these methods has proven to be uniformly superior. Consequently, we apply these three methods (FM-OLS, CCR and DOLS) to estimate the child labour equation and compare the results.

Another key point in this research is the selection of proxy variables for legislation, education, demography, income, and technology. Ideally, one would like to consider simultaneously several distinct proxy variables for each category to estimate the long-run partial effect of each driver included in the different dimensions. However, the fact that the child labour rate data is a medium-sized sample does not allow the inclusion of an unbounded number of variables on the right-hand side of Eq. (1). In fact, there is a complicated balance between including enough covariates to avoid underspecifying the model and, at the same time, not so large that generates overfitting regression problems and loss of too many degrees of freedom. Hence, we decided to estimate models with 5 and 6 covariates with, at least, one variable per each identified factor (legislation, schooling, demographics, income, and technology). Additional considerations about the selected models are provided in Sect. 5.2.

5 Empirical Results and Discussion

This Section reports and discusses the results obtained from applying the empirical methodology described in Sect. 4.

5.1 Testing for a Unit Root in the Child Labour Data

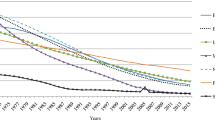

Figures 1 and 2 show the time plot of Portugal’s annual and decadal child labour rate, respectively, whilst the percentage point variation of child labour in the period studied is plotted in Fig. 3. The time plot of Portugal’s child labour series reveals a clear downward pattern that illustrates the steady decline of the percentage of working children from the age group 10–14 throughout the second half of the twentieth century.

Figures 2 and 3 shed light on how this decline took place. They particularly show a consistent trend over the period studied and minor fluctuations, with the child labour rate decreasing from 49% in the late 1930s to 4% in the mid-1990s. The incidence of child labour seems to remain constant around 49% in the first ten years of the reporting period. However, from 1945 onwards, it followed a marked and steady decline, when the incidence of child labour decreased, on average, by 9 percentage points per decade. Thus, child labour declined to 40% in 1955 and by 1965 it dropped to 31%. The downward trend was particularly marked and noticeable in the following decade, where child labour decreased by 12 percentage points, reaching 19% in 1975. By 1985, the child labour rate dropped further to 13%, continuing to decrease, reaching its lowest level at 4% by 1994, at the end of the reporting period.

The variables listed in Sect. 3 as proxies for legislation, schooling, demographics, income, and technology are also illustrated in Fig. 1. The time plots of the candidate explanatory variables reveal clear downward or upward trending behaviours which suggest that these time series are non-stationary. To reinforce these findings, we implement several statistical procedures to test for the presence of a unit root in these series. As a benchmark, we applied the popular ADF (Dickey & Fuller, 1979), PP (Phillips & Perron, 1988) and KPSS (Kwiatkowski et al., 1992) tests. To obtain unit root tests with better power properties, Elliott et al. (1996) proposed the ADF-GLS and PT statistics. On a further trial to enhance the statistical power while mitigating eventual size distortions, Ng and Perron (2001) proposed modified versions of existing unit root statistics, denoted as MZa, MZt, MSB and MPT. All these have been implemented here. Almost all these statistics consider the presence of a unit root as the null hypothesis. The exception is the KPSS that sets the series to be I(0) under the null. There is a vast literature on unit root testing (Choi, 2015) but these seem to be the most well-known unit root statistics and are directly implemented in most econometric software packages. Table 2 shows the results of all these unit root testing procedures applied to the child labour rate and the considered determinants. Naturally, the unit root tests were not applied to the minimum working age and compulsory schooling legislation. We included a constant and a trend in the auxiliary regression required to implement these tests as it is recommended for series with clear time trends as the ones observed in Fig. 1.

We highlight that, for most of the variables, the unit root null hypothesis was not rejected even at the 10% level, regardless of the test statistic being analysed. On the other hand, the KPSS statistic rejected the null of (stochastic) stationarity for all series, at least at the 10% level, except for child_labour and log(wage). Hence, for almost all series, the conclusion of the presence of a unit root is reinforced by the KPSS test.

5.2 Testing for Cointegration in the Child Labour Data

Since the results of the unit root tests in Sect. 5.1 suggest that the time series representing legislation, education, demographics, income and technology factors are I(1), we can proceed to determine if cointegrating relationships may be found between the child labour rate and these variables. To do so, we apply the Engle-Granger method and test if the OLS residuals of regressions with the format of Eq. (1) are I(0) or I(1). If the series are not cointegrated such that \({u}_{t}\sim I(1)\), the regression will be spurious and can lead to quite misleading results. On the other hand, if there is cointegration such that \({u}_{t}\sim I(0)\), Eq. (1) will define a long-run relationship between child labour and the considered covariates and we can estimate the models by FM-OLS, CCR or DOLS to obtain reliable estimates and test statistics for the slope coefficients.

The original dataset described in Sect. 3 still allows an impressive number of models with different combinations of variables. Hence and as mentioned before, we considered models with 5 and 6 covariates and, at least, one variable per factor. Moreover, we only considered models with evidence of cointegration, based on the Engle-Granger approach, so that the estimation results do not fall into the problems of spurious regressions. This model selection process resulted in 26 cointegrating regressions whose estimation output is reported in Tables 3–14.

Proceeding to the specifics of the Engle-Granger procedure, we recall that it tests for the presence of a unit root in the residuals, and it is well known that the properties of this type of test are affected by the presence of serial correlation. We follow the most common way to deal with this problem and augment the auxiliary regression with lagged changes of the tested series (Dickey & Fuller, 1979). We have chosen the number of lagged changes of the residuals according to the Akaike Information Criterion with an upper bound of 3 lags. The critical values were obtained from the surface regression approach of MacKinnon (2010) based on the estimates of Table 2 of that paper.

The row named EG of Tables 3–14. reports the Engle-Granger statistic and informs whether its value is low enough to reject the null of no cointegration at 1%, 5% or 10% level. Notice that it is sufficient to analyse the results of the Engle-Granger test from Table 3 until 6 as the remaining tables repeat the same specifications but with other methods to estimate the unknown coefficients in Eq. (1). As can be seen, the null hypothesis of no cointegration is rejected for the regressions with 5 covariates at the 10% level. The evidence of cointegration becomes stronger when we consider specifications with 6 covariates as the Engle-Granger test rejects the null hypothesis at 1% or 5% for several cases. Hence, the results of the tests show evidence of cointegration between the set of variables considered in each specification and Portugal’s child labour at 10% or, many times, at a lower significance level. Overall, the testing procedures suggest that the cointegrating regressions from Tables 3–14. are valid to characterize long-run relationships between child labour rate and the variables selected to represent the legislation, education, demographics, income, and technology dimensions.

5.3 Describing the Long-Run Relationships Between Child Labour and Factors Related to Legislation, Education, Demographic, Income and Technology

We now go through the different regression specifications to characterize child labour dynamics, analyse the estimation results of each factor, and discuss the main findings of this paper. Despite the model selection process described in Sect. 5.2, we still have a good number of results to report. Hence, we distinguish the estimation output by estimation method and number of covariates. In particular, the slope coefficients of the child labour rate equations fitted by DOLS, FMOLS and CCR are reported in Table Tables 3–14, respectively. Moreover, Table 3, 7 and 11 report the estimation results with 5 covariates whereas the remaining tables show the output with 6 covariates. Finally, Table 6, 10 and 14 consider specifications which include ratio_mf_wage and land_prod_maize as variables which may have contributed to changes in some aspects of the demographic and technological dimensions, respectively. Information about the statistical significance of each coefficient (*, **, and *** correspond to statistical significance at 10%, 5% and 1%, respectively) is also provided in all tables. We focus most of our attention on the results of the DOLS cointegrating regressions, but we highlight that only small differences have been found when other estimation methods are employed which are mentioned throughout this section. Hence, the estimation results from the other methods (FMOLS and CCR) are reported in Appendix (Table 7–14).

Considering first the variables selected to capture the effects of legislation on child labour, in 67% of the specifications fitted by DOLS which include min_age as a covariate, the coefficient on min_age is significantly different from zero at least at the 5% level. As for the models which use school_years as a control for the legislation factor, only 2 out of the 12 estimated models show a statistically significant coefficient on this variable. We obtain analogous results from the FMOLS and CCR regressions (see Appendix). Hence, a first important finding from this paper is that, in general, we find weak evidence that the increase in the number of compulsory schooling years contributed to Portugal’s child labour decrease. This may be explained by the fact that most relevant changes in this type of legislation were introduced on periods with already relatively high enrolment rates of children in schooling as it can be inferred from the plots of school_years and enrol in Fig. 1, respectively. The results for the min_age are somewhat different and sensitive to the specification, although the majority of the considered regressions point out that changes in the minimum start working age had a relevant impact on Portugal’s child labour decrease. As discussed in Sect. 2.1, this seems partially consistent with the experience of other core European economies, such as the case of Britain with the Factory Act (Cunningham & Viazzo, 1996), but also in contrast with other cases such as the US (Moehling, 1999). However, the comparison of specifications 1, 10–11 against 2–4 reveals that the coefficient of min_age becomes much lower in magnitude and loses some significance when the income factor is controlled by gdp_pc (this result is more apparent in the FMOLS and CCR estimation results). A plausible explanation for this issue could be that the coefficients from specifications 2–4 are amplified by omitted variable bias because a country with higher income per capita tends to have better labour legislation, including a higher minimum working age. Although historical accounts suggest an intricate and diverse relationship between legislation, children’s work and economic growth across contexts (Humphries, 2003), we acknowledge this issue could be reflected in the case of peripheral Portugal. If that is the case, this finding reinforces the importance of other factors beyond legislation, such as income, to explain the decline in child labour in Portugal. On the other hand, as we elaborate in Sect. 2.1, the key issue regarding child labour legislation may not be the adoption of certain regulations per se, but enforcement. This seems particularly true for the rural sector, where monitoring often proves to be challenging, particularly on small farms, where the nature of agricultural and seasonal/informal activities complicated regulatory oversight. Indeed, in the case of Portugal, child labour has been largely prevalent in agriculture, especially in central regions such as Alentejo, but on the periphery of policy discussions and monitoring (Goulart & Bedi, 2017). Unfortunately, we cannot test enforcement dynamics in our analysis. Hence, it may still be a matter of debate whether a tighter legal framework forbidding child labour contributed to the child labour decline, although our results are more favourable to the conclusion that, in fact, this occurred in the context of peripheral Portugal.Footnote 12

As for the variables related to education, the DOLS ratio_pt_prim and enrol coefficient estimates range between 0.316 and 0.867 and − 0.172 and − 0.038, respectively, and are, in general, statistically significant at the 10% or at smaller levels. These results suggest that child labour is positively related to the student–teacher ratio in primary school and negatively related to primary enrolment. Figure 1 shows that the student–teacher ratio in primary school decreased and primary enrolment increased throughout the sample period. This provides empirical support that, in general, aspects related to school enrolment and school quality linked with class size had a relevant impact on the fall of child labour in Portugal. These results are quite robust as the same conclusions can be taken regardless of the estimation method and for most of the reported models where either enrol or ratio_pt_prim or both act as a control for education.

As for the proxies for the demographic transition, we obtained positive and statistically significant DOLS coefficients for inf_mort in 6 out of 10 specifications that included this variable. On the other hand, the coefficient estimates for ch_pop are not statistically different from zero for about 69% of the DOLS regressions. We obtain similar results when we fit the models by FMOLS and CCR (in Appendix). Specifications 20 until 24 include ratio_mf_wage as an additional proxy for demographics and here most of the displayed equations report positive and statistically significant coefficients with more robust results under the DOLS method. In this sense, regarding traditional demographic factors, we obtain more mixed findings in comparison with the other factors explaining child labour. Yet, for Portugal, it seems that the gender wage gap played an important role in the long-run decrease of child labour. As discussed in Sect. 2.3, this is coherent with the importance attributed to female labour force participation for substituting child time allocation from work to school, as also discussed by Horrell and Humphries (1995a; 1995b). Regarding the nexus between demographic transition and child labour decline, these findings might thus align the experience of peripheral Portugal with other first industrialized countries, such as Britain.

As regards to the series representative of the income factor, we find a negative and statistically significant coefficient for gdp_pc for almost all considered specifications, independently of the estimation method employed. We also obtain DOLS coefficients with negative signs and statistically significant at 1% or 5% level for the gov_exp and wage in almost all cases as can be seen, for example, in Eqs. 2 until 4 or 6 until 9. As for the FMOLS and CCR methods (in Appendix), we obtain similar results for the wage variable whereas the statistical significance and magnitude of the gov_exp coefficient become more sensitive to the considered specification. These facts highlight the relevant ceteris paribus association between the increase in income per capita levels and the fall of participation of children in the labour force. This evidence has also been already observed in other countries (Sect. 2.4), such as Britain (Nardinelli, 1990) and the core European economies (Fallon & Tzannatos, 1998), but also in today’s developing countries (Edmonds, 2003), suggesting that increasing income level of households also had a relevant impact for child labour decline in the periphery.

Finally, our results imply that technological progress contributing to better productivity in the agricultural and industrial sectors has been important for reducing child labour. In particular, specifications 12, 14, 15, 17, 25, and 26 consider regressions where log(land_prod_wheat) or log(land_prod_maize) are included as covariates, whereas the remaining ones use log(value_added_pw) as a technological factor. Whilst child labour has been common in the agricultural sector for the period in analysis (Goulart & Bedi, 2017), technological changes, and the resulting increased sectoral productivity and structural change, might have implied a substantial reduction in child labour in the overall economy. Indeed, we observe that the indicators about land productivity and value added in industry per worker had a negative and strongly statistically significant impact on the level of Portugal’s child labour, with the magnitude and statistical significance of the coefficients of log(value_added_pw) and log(land_prod_wheat) being reasonably robust and stable across different specifications and estimation techniques. This may be explained by the fact that technological advances enhancing productivity in agriculture and industry changed the labour force structure, making less necessary to perform certain tasks that typically employed children and raising adult workers’ wages and employment. This implied a substantial reduction on the demand for child labour, in line with Reis (2004).

All these findings suggest that complementary factors beyond legislation have been important in curbing child labour, as discussed in Sect. 2.5. In relation to this, the historical experience of peripheral Portugal seems to be, at least to a certain extent, different from those of the first industrializers, where technological innovations initially introduced following industrialization seem to have been complementary to the employment of children, as in the case of England (Tuttle, 2009) or Belgium (De Herdt, 2011). Yet, differences are also detected within the periphery, and the positive role of technology in Portugal’s child labour decline seems in contrast with accounts from Catalonia (Camps, 1996), where industrialization might have put pressure on child labour demand. Particularly, the case of peripheral Portugal highlights the structural role of technology, especially in child-intensive sectors such as agriculture. In this context, increasing skill requirements and improved agricultural productivity gradually led to the exclusion of children from the sectoral labour market over time. Given the magnitude of the phenomenon in the sector, this implied a significant reduction in child labour in the overall economy in the long-run.

5.4 Discussion of the Main Results

The “traditional view” gives strong weight to the importance of laws forbidding labour up to a certain age in fighting the child labour problem. This idea has been largely based on historical accounts from historically leading countries, such as Britain (Cunningham & Viazzo, 1996).

Our results are, to some degree, favourable that minimum working age legislation had an impact on child labour, but a mixture of other factors seems also to be more important in explaining this societal change. The historical role of increasing income for curbing the work of children is consistently confirmed in our results, and higher income level of households had a relevant impact for child labour decline in peripheral Portugal in the past. Besides stricter regulations and economic growth, we also find that other three dimensions had a prominent role in curbing Portuguese child labour, namely schooling, demography and technology. Firstly, compulsory education, and particularly increasing school enrolment and school quality, were important to attenuate the problem of child labour. Secondly, our empirical evidence is somewhat inconclusive in terms of the role played by pure demographic variables, but historical changes in the role of women in the labour market seem to have stimulated a change in behaviour towards child labour, as also happened in other first industrialized countries in the short run.

Finally, our results also suggest that technological progress enhancing productivity in agriculture and industry played a significant role in curbing child labour levels by reducing the need for children to work. In this context, technological advances boost the marginal productivity of adult workers, raising their wages and employment and reducing the need for child labour. These results on technology in peripheral Portugal seem to differ, at least to a certain extent, from those from certain early industrializers, where initial mechanization might have been complementary to the employment of children. The case of Portugal thus highlights the historical importance of enhanced productivity and higher-skill requirements. This dynamic is likely to have been particularly relevant in child intensive sectors, such as agriculture (Goulart & Bedi, 2017).

All these findings have shown to be robust to alternative methods to estimate cointegrating regressions and to different model specifications where we alternate covariates representing each dimension.

Overall, these findings suggest that to curb child labour, policymakers should consider alternative factors beyond legislation, such as the role played by school enrolment and school quality, income support to vulnerable families, technological progress directed to sectors employing more children, and the role of women in the labour market. Moreover, our results provide empirical evidence on the role played by different factors for the child labour decline in peripheral Europe, some in common with certain first industrializers, while others highlight the peculiarity of peripheral experiences. This confirms the diversity of historical trajectories of child labour across both peripheral and core and industrial economies.

6 Concluding Remarks

This paper provides a first empirical assessment of the driving factors of the historical decline of Portugal’s child labour, a country in Europe’s periphery. While there is a vast literature about child labour, there are few works that describe and explain the historical path of child labour in Southern Europe. For this purpose, we identify legislation, schooling, demography, income, and technology as the main dimensions contributing to the decline of child labour and build a dataset composed by the annual time series of Portugal’s child labour rate and several variables related to these dimensions. After confirming the presence of a unit root in our time series data, we carry out a cointegration analysis to estimate and study the long-run relationship between child labour and the considered factors.

Studying the experience of peripheral Portugal, our research suggests that, generally, both minimum age and compulsory schooling laws contributed less than other dimensions in the historical decline of child labour. In particular, there seem to be strong and robust long-run relations between child labour and other alternative factors related to education, demography, income and technology.

These findings imply that policymakers may need to address different factors when designing policies to attenuate the child labour problem. They also confirm that explanations for the observed child labour decline may differ by country and socio-economic contexts and, particularly, between peripheral and core and industrial economies, introducing a more nuanced view of the existing literature.

Last, we acknowledge that there may be reverse causality between some variables representing the demographic and income factors and child labour. For example, whether fertility and child labour decisions interact or follow a one-way causal relationship has been a matter of debate in the literature, as discussed in Sect. 2.3. Moreover, if children are considered closer substitutes to women than men, the reduction in child labour would impact the relative wages of women. If there is reverse causality, the coefficients of the regressions that include these variables will be biased and inconsistent. Since the estimation methods implemented in the paper (DOLS, FM-OLS, and CCR) have been developed to remove the asymptotic second-order bias effects in the \(\beta s\) caused by autocorrelation and endogeneity of the regressors, we may expect some reduction of the bias given the number of time periods of our dataset. As a further confirmation check, we fitted the regressions reported in Table 4, 5, 6 but where either ch_pop, ratio_mf_wage, or log(wage) were excluded from the model. The results reveal that the estimates of the \(\beta s\) from these alternative specifications share similar properties in terms of signal and statistical significance. Hence, the core messages discussed in this paper remain fundamentally unaltered regardless of whether the variables ch_pop, ratio_mf_wage, or log(wage) are included or excluded from the models.

Nevertheless, as future research, it would be worthwhile to find convincing instrumental variables for the endogenous variables and compare the results of a two-stage least squares approach with our time series approach.

The variables included in the models are the result of a selection process from the literature review and background detailed in Sect. 2. Another possible research opportunity is to consider Lasso and machine learning as alternative techniques to select the variables that should be included in the models so that it is possible to understand what really drove Portugal’s child labour decline. However, applying this type of technique in our setting may be challenging as we are using a medium-sized sample with time series that seem to follow integrated and cointegrated processes.

Notes

The Industrial Revolution originated in England in the 1760s and spread to other European countries thereafter.

For instance, the United Kingdom introduced legislation banning the employment of children, in industry, below the age of 9 in 1833, this was followed by an 1878 act which raised the minimum age to 10 and then to 12 in 1901. France and Sweden introduced legislation setting a minimum working age in the 1840s, Germany in the 1850s, Denmark, Finland, The Netherlands and Spain in the 1870s and Belgium, Russia in the 1880s (Williams, 1992; Hindman H., 2009a).

For U.S., compulsory schooling laws had modest effects on promoting schooling as schooling was already largely available and free of charge (Goldin & Katz, 2003).

Similarly, an increase in the gap between skilled and unskilled wages is likely to lead to a reduction in the attractiveness of child labour and an increase in the attractiveness of education.

While this paragraph discusses eventual changes prompted by wage increases, others have suggested that even without wage changes and in very poor settings it is possible to stop child labour. MV Foundation in India uses civil society driven change (by community peer pressure) for children to stop working and joining school (Wazir, 2002).

The point here is not that there is a net increase in working children, but that the rationale for employing children working is driven by their greater efficiency. This was also noted by Karl Marx in Capital (Heywood, 2009b: 515).

The loss of 364,928 cases is mainly due to the exclusion of those who did not report information on the year they started working for the first time. These cases are randomly distributed across the years studied.

In our methodology, individuals declaring to have started working before reaching the age limit under consideration will be counted as working when they were between 10–14 years old.

We acknowledge our choice of a fixed age-based approach may imply limitations in the measurement of child labour by, for instance, neglecting the work of children under 10 years old. However, we follow seminal works in the literature such as Toniolo and Vecchi (2007: p. 404) and assume the shortcoming of our estimate to be relatively small given that, during the last century, European children under the age of 10 were already modestly contributing to production processes in other Southern European countries.

Ideally, school participation, such as attendance ratios, would be better to serve as a proxy for schooling. However, continuous data for this dimension is unavailable for the studied period in Portugal. Alternatively, we have used primary enrolment. Enrolment per se cannot perfectly represent changes in primary school attendance, since a child can be enrolled but not attending. Nevertheless, it has frequently been used in the literature, particularly when recurring to historical data.

We also analysed the results of the interaction between legislation and educational policies as these policies may not work in isolation. Specifically, we augmented the fitted models that have both min_age and school_years (specifications 6 to 9) with the regressor min_age*school_years. Beyond econometric concerns related to the fact that the cointegrating regression is now non-linear, we obtained a positive coefficient for the interaction term in all specifications (the complete estimation outputs are available upon request). This implies that educational policies, such as changes in the number of compulsory schooling years, are less effective in reducing child labour in a context of already higher legally determined thresholds for the minimum working age. Following the same reasoning, it also implies that changes in legislation, such as setting a higher minimum working age, contribute less to decreasing child labour in a setting where children have more years of compulsory schooling. We are grateful to a reviewer for suggesting that we explore this possibility.

References

Admassie, A., & Bedi, A. (2008). Attending School, Reading, Writing and Child Work in Rural Ethiopia. In J. Fanelli & L. Squire (Eds.), Economic reforms in developing countries: Reach, range, reason (pp. 185–225). Edward Elgar.

Banerjee, A., Dolado, J., Hendry, D., & Smith, G. (1986). Exploring equilibrium relationships in econometrics through static models: Some Monte-Carlo evidence. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 48, 253–277.

Basu, K. (1999). Child labor: Cause, consequence, and cure, with remarks on international labor standards. Journal of Economic Literature, 37(3), 1083–1119.

Becker, G. (1992). Fertility and the economy. Journal of Population Economics, 5(3), 185–201.

Bhalotra, S., & Heady, C. (2003). Child farm labor: The wealth paradox. The World Bank Economic Review, 17(2), 197–227.

Bolin-Hort, P. (1989). Family and the State: Child labour and the Organization of Production in the British Cotton Industry, 1780–1920. Lund University Press.

Brown, M., Christiansen, J., & Philips, P. (1992). The Decline of Child Labor in the U.S. Fruit and Vegetable Canning Industry: Law or Economics? Business History Review, 66(4), 723–770.

Camps, E. (1996). Family strategies and children’s work patterns: Some insights from industrializing Catalonia, 1850–1920. In H. Cunningham, & P. Viazzo, Child Labour in Historical Perspective (pp. 57–71). Florence: UNICEF International Child Development Centre.

Cappuccio, N., & Lubian, D. (2001). Estimation and inference on long-run equilibria: A simulation study. Econometric Reviews, 20(1), 61–84.

Choi, I. (2015). Almost all about unit roots: Foundations, developments, and applications. Cambridge University Press.

Choi, I., & Kurozumi, E. (2012). Model selection criteria for the leads-and-lags cointegrating regression. Journal of Econometrics, 169(2), 224–238.

Christou, C., & Pittis, N. (2002). Kernel and bandwidth selection, prewhitening, and the performance of the fully modified least squares estimation method. Econometric Theory, 18(4), 948–961.

Clio-infra project. Clio Infra: Reconstructing Global Inequality. 01 January, 2019, from https://www.clio-infra.eu/

Cunningham, H. (2000). The decline of child labour: Labour markets and family economies in Europe and North America since 1830. Economic History Review, 53(3), 409–428.

Cunningham, H. (2001). The rights of the child and the wrongs of child labour: An historical perspective. In K. L. White, Child labour: Policy options. Aksant Academic Publishers.

Cunningham, H., & Stromquist, S. (2005). Child Labor and the Rights of Children. In B. H. Weston, Child labour and Human rights. Making Children Matter. Lynne Rienner Publishers.

Cunningham, H., & Viazzo, P. (1996). Some Issues in the Historical Study of Child Labour. In H. Cunningham, & P. Viazzo, Child Labour in Historical Perspective. UNICEF International Child Development Centre.

Dayioğlu, M. (2006). The impact of household income on child labour in urban Turkey. The Journal of Development Studies, 42(6), 939–956.

Dayioglu, M., & Kırdar, M. (2020). Keeping Kids in School and Out of Work: Compulsory Schooling and Child Labor in Turkey. IZA Discussion Papers from Institute of Labor Economics (IZA), 13276.

de Carvalho Filho, I. (2012). Household Income as a Determinant of Child Labor and School Enrollment in Brazil: Evidence from a Social Security Reform. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 60(2), 399–435.

De Herdt, R. (2011). Child Labour in Belgium: 1800–1914. In K. Lieten, & E. Nederveen Meerkerk, Child Labour’s Global Past, 1650–2000. Peter Lang.

DeGraff, D. S., Ferro, A. R., & Levison, D. (2016). In Harm’s way: Children’s work in risky occupations in Brazil. Journal of International Development, 28(4), 447–472.

Dessy, S. (2001). A defence of compulsive measures against child labour. Journal of Development Economics, 62, 261–275.

Dickey, D., & Fuller, W. (1979). Distribution of the estimators for autoregressive time series with a unit root. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 74(366a), 427–431.

Dyson, T. (1991). Child labour and fertility: An overview, an assessment and an alternative framework. In R. Kanbargi, Child labour in the Indian subcontinent. Dimensions and Implications. Sage Publications.

Eastwood, R., & Lipton, M. (2003). Demographic transition and poverty: effects via economic growth, distribution and conversion. In N. Birdsall, C. Kelley, & S. Sinding, Population matters. Demographic change, economic growth, and poverty in the developing world. Oxford University Press.

Eaton, M., & Goulart, P. (2009). Portuguese child labour: An enduring tale of exploitation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 16, 439–444.

Edmonds, E. (2003). Does child labor decline with improving economic status? NBER Working Paper 10134.

Edmonds, E. (2007). Child Labor. In P. Schultz, & J. Strauss, Handbook of Development Economics (pp. 3607–3709). Elsevier.

Edmonds, E., & Shrestha, M. (2012). The impact of minimum age of employment regulation on child labor and schooling. IZA J Labor Policy, 1(14), 1.

Edmonds, E., & Theoharides, C. (2020). Child Labor and Economic Development. In Zimmermann, Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics. Springer.

Effland, A. (2005). Agrarianism and child labor policy for agriculture. Agricultural History, 79(3), 281–297.

Elliott, G., Rothenberg, T. J., & Stock, J. (1996). Efficient tests for an autoregressive unit root. Econometrica, 64(4), 813–836.

Emerson, P. M. (2009). The Economic View of Child Labor. In H. D. Hindman (Ed.), The world of child labour. An Historical and Regional Survey. Sharpe.

Fallon, P., & Tzannatos, Z. (1998). Child labor: issues and directions for the World Bank. World Bank.

Fyfe, A. (2009). Coming to Terms with Child Labor: The Historical Role of Education. In H. D. Hindman, The World of Child Labour. An Historical and Regional . New York: M.E. Sharpe. New York: M.E. Sharpe.

Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (1996). The Gender Gap, Fertility, and Growth. American Economic Review, 86(3), 374–387.

Galor, O., & Weil, D. N. (2000). Population, Technology and Growth: From Malthusian Stagnation to the Demographic Transition and Beyond. American Economic Review, 90(4), 806–828.

Goldin, C. (1979). Household and market production of families in a late nineteenth century American town. Explorations in Economic History, 16(2), 111–131.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. (2003). Mass secondary schooling and the state: The role of state compulsion in the high school movement. NBER Working Paper 10075.

Goulart, P., & Bedi, A. S. (2017). The evolution of child labor in Portugal, 1850–2001. Social Science History, 41(2), 227–254.

Hammond, J., & Hammond, B. (1917). The town labourer, 1760–1832.

Hazan, M., & Berdugo, B. (2002). Child labour, fertility and economic growth. Economic Journal, 112(482), 810–828.

Hazarika, G., & Bedi, A. S. (2003). Schooling costs and child work in rural Pakistan. Journal of Development Studies, 39(5), 29–64.

Heywood, C. (2009). A Brief Historiography of Child Labor. In H. D. Hindman (Ed.), The world of child labour. An historical and regional survey. M.E. Sharpe.

Hindman, H. (2009a). The world of child labour. An historical and regional survey. M.E. Sharpe.

Hindman, H. D. (2009b). Coming to terms with child. In H. D. Hindman (Ed.), The world of child labour. An historical and regional survey. Sharpe: M.E.

Horrel, S., & Humphries, J. (1995). The exploitation of little children: Child labor and the family economy in the industrial revolution. Explorations in Economic History, 32(4), 485–516.

Horrell, S., & Humphries, J. (1995). Women’s labour force participation and the transition to the male-breadwinner family, 1790–1865. Economic History Review, 48, 89–117.

Huberman, M., & Meissner, C. (2010). Riding the wave of trade: The rise of labor regulation in the golden age of globalization. The Journal of Economic History, 70(3), 657–685.

Humphries, J. (2003). Child Labor: Lessons from the Historical Experience of Today’s Industrial Economies. The World Bank Economic Review, 17(2), 175–196.

Hutchins, B., & Harrison, A. (1926). A history of factory legislation.

ILO. (1998). Child labour: Targeting the intolerable, 86th session, international labour conference. International Labour Office.

Inder, B. (1993). Estimating long-run relationships in economics: A comparison of different approaches. Journal of Econometrics, 57(1–3), 53–68.

Kambhampati, U., & Rajan, R. (2006). Economic growth: A panacea for child labor? World Development, 34(3), 426–445.

Krauss, A. (2017). Understanding child labour beyond the standard economic assumption of monetary poverty. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 41(2), 545–574.

Kwiatkowski, D., Phillips, P., Schmidt, P., & Shin, Y. (1992). Testing the null hypothesis of stationarity against the alternative of a unit root: How sure are we that economic time series have a unit root? Journal of Econometrics, 54(1–3), 159–178.

Kyyrä, T., & Wilke, R. A. (2014). On the reliability of retrospective unemployment information in European household panel data. Empirical Economics, 46, 1473–1493.

Lains, P. (2003). Catching up to the European core: Portuguese economic growth, 1910–1990. Explorations in Economic History, 40(4), 369–386.

Levy, V. (1985). Cropping pattern, mechanization, child labour, and fertility behaviour in a farming economy: Rural egypt. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 33(4), 777–791.

MacKinnon, J. (2010). Critical values for cointegration tests. Queen's Economics Department Working Paper(1227 ).

Maddison. (2013). Maddison Project. Retrieved 01 01, 2019, from http://www.ggdc.net/maddison/maddison-project/home.htm.

Mincer, J. (1962). Labor force participation of married women. In H. Lewis (Ed.), Aspects of labor economics. NBER.

Mitchell, B. (2007). International Historical Statistics, Europe 1750–2005. Palgrave.

Moehling, C. (1999). State child labor laws and the decline of child labor. Explorations in Economic History, 36(1), 72–106.

Montalvo, J. (1995). Comparing cointegrating regression estimators: Some additional Monte Carlo results. Economics Letters, 48(3–4), 229–234.

Nardinelli, C. (1980). Child labor and the factory acts. Journal of Economic History, 40(4), 739–755.

Nardinelli, C. (1990). Child labor and the industrial revolution. Indian University Press.

Ng, S., & Perron, P. (2001). Lag length selection and the construction of unit root tests with good size and power. Econometrica, 69(6), 1519–1554.

Park, J. (1992). Canonical cointegrating regressions. Econometrica, 1, 119–143.

Pereirinha, J. A., Arcanjo, M. & Carolo, D. F. (2009). Prestações sociais no corporativismo português: a política de apoio à família no período do Estado Novo". Instituto Superior de Economia e Gestão—GHES Documento de Trabalho/Working Paper nº 35–2009.

Phillips, P., & Durlauf, S. (1986). Multiple time series regression with integrated processes. The Review of Economic Studies, 53(4), 473–495.

Phillips, P., & Hansen, B. (1990). Statistical inference in instrumental variables regression with I (1) processes. The Review of Economic Studies, 57(1), 99–125.

Phillips, P., & Perron, P. (1988). Testing for a unit root in time series regression. Biometrika, 75(2), 335–346.

Pordata. PORDATA - Estatísticas, gráficos e indicadores. https://www.pordata.pt/

Puerta, J. (2010). What saved the children? Child labor laws and the decline of child labor in the U.S. (1900–1920). Mimeo.

Ravallion, M., & Wodon, Q. (2000). Does Child Labour Displace Schooling? Evidence on behavioural responses to an enrollment subsidy. Economic Journal, 110(462), 158–175.

Reis, J. (2004). Human capital and industrialization: The case of a late comer—Portugal, 1890. In J. Lungbjerg (Ed.), Technology and human capital in historical perspective (pp. 22–48). Palgrave Macmillan.

Rosenzweig, M. (1981). Household and non-household activities of youths: Issues of modeling, data and estimation strategies. In G. Rodgers & G. Standing (Eds.), Child work, poverty and underdevelopment. ILO.

Rosenzweig, M., & Evenson, R. (1977). Fertility, schooling and the economic contribution of children in Rural India: An economic analysis. Econometrica, 45(5), 1065–1079.

Saikkonen, P. (1991). Asymptotically efficient estimation of cointegration regressions. Econometric Theory, 7(1), 1–21.

Schultz, T. (1964). Transforming traditional agriculture. Yale University Press.

Shanan, Y. (2023). The effect of compulsory schooling laws and child labor restrictions on fertility: Evidence from the early twentieth century. Journal of Population Economics, 36, 321–358.

Shattuck, R. M., & Rendall, M. S. (2017). Retrospective reporting of first employment in the life-courses of U.S. Women. Sociological Methodology, 47(1), 307–344.