Abstract

The study assesses the effect of inclusive education on health performance in 48 Sub Saharan African countries from 2000 to 2020. The study adopted the Driscoll/Kraay technique to address cross-sectional dependence and the GMM strategy to address potential endogeneity. The study employed three indicators of health performance which are the total life expectancy, the female life expectancy and the male life expectancy. Three gender parity index of educational enrolments are employed: primary education, secondary and the tertiary education as indicators of inclusive education. The findings of the study reveal that inclusive education enhances the health situation of individuals in Sub Saharan Africa. The findings further show that the health situation of both the male and the female are improved by inclusive education. The study recommends policymakers in this region to invest more in the education and the health sector so as to enhance the health performance of the citizens.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Education is considered an important factor which is known to influence health performance and inequalities in life expectancy (Asongu et al., 2021). Education in every society serves as a right for individuals and a principal component that determines socioeconomic status which tends to influence livelihood, especially in its dimension of health status. Its importance is confirmed in the sustainable development goal (SDG4) which is aimed at “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities”. In many developing countries, life expectancy remains very low due to a lack of investments in human capital development where many children still have no access to education and health facilities (Bado and Susuman, 2016). The case in Sub-Saharan African countries is striking, with the rate of school dropped out still very high. In early 2018, UNESCO reported that 258.4 million children globally, youth and adolescents were out of school, representing one-sixth of the global population of the youth age group. The report further confirmed that one dropout is registered out of five children in sub-Saharan Africa in 2018.

The links between life expectancy and education are well documented in literature both contemporary and non-contemporary literature (Sen, 1999; Saito, 2003; Hansen & Strulik, 2017; Olshansky et al., 2012; Hendi, 2017). According to Sen (1999), quality education is fundamental to maintaining a healthy lifestyle and well-being. Countries with well-established knowledge economies have higher standards of living and life expectancy relative to economies whose educational sectors are neglected (Asongu et al., 2020; Hansen & Strulik, 2017). Educated people pay for more nutritious food and quality medical care, which promotes a healthy lifestyle than individuals who do not monitor their health situation (Luy et al., 2019; Meara et al., 2008). Similarly, education influences health through the adoption of healthier lifestyles, better diets, and more effective management of chronic diseases (Olshansky et al., 2012). Higher education gained by citizens in developed countries enhances their socioeconomic status gradient and the amounts of their longevity. Health performance is greatly determined by the number of death in the first year of life, indicated by infant mortality and death in the first five years of life indicated by the under-five mortality rate. In Sub-Saharan African, about 4.8 million children die before the age of five annually, which translates to 9 deaths every minute and signifying poor health conditions (Anyamele et al., 2017). These rates have been very high in Sub-Saharan Africa which accounts for 45% of the world's child mortality (UN Inter-Agency Group 2012). The report of the World Bank shows that the number of under-five mortality has dropped drastically from 151 in 2000 to 73 in 2020 with the West and Central African countries recording the highest than the Eastern and Southern sub-Saharan African countries.

However, the problem of gender disparities in adult literacy rates in Sub-Saharan Africa remains wide due to both cultural factors and lack of infrastructure, which greatly affect the health of individuals. These disparities are widely recorded between women but shreds of evidence indicate that some progress has been made at the regional and country levels to reduce health inequalities and the literacy level of women (Bad and Susuman, 2016). The Mortality rate of infants per 1,000 live births in Sub-Saharan Africa has decreased drastically over the years. In 2000, Sub-Saharan African countries recorded 91 deaths per 10,000 live births which reduce to 65 in 2010 and 50 in 2020. This decrease in infant mortality rate is attributed by the World Bank to an increase in investments in the health sector. According to Hoffman-Terry et al. (1992) and So et al. (2012), this falling mortality rate is due to increased immunizations and oral rehydration. Tremendous efforts have been made to improve the access to healthcare for children in Sub-Saharan African countries leading to a decrease in the death rate per 1000 of the population (Bado and Susuman, 2016).

As a critic of the studies conducted in the literature investigating the effect of education on health performance in Sub-Saharan Africa, there is no consideration of the gender parity in inclusive education and the differences in educational levels. Similarly, the health performance of individuals with differences in educational levels has provided mixed results, though attributed by Hendi (2017) to results from differences in health performance indicators. In addition, these studies conducted on the effect of education on health performance have not considered the differences in female and male life expectancies which have been addressed in our study. The contribution of the study to the field of research is drawn from the limitations of existing studies. To the best of our knowledge, this is still the first study to be conducted on inclusive education and health performance in Sub-Saharan Africa. The study conducted in Africa that is closely related to our study is that of Guisan and Exposito (2016) who examined the link between education and life expectancy. In their study, they employed education as a composite indicator without accounting for different levels of educational enrolment. Among the fewer studies conducted on education and life expectancy in Africa, none has considered measuring education inclusively at a gender parity index. This study considered primary, secondary and tertiary education to account for differences at educational levels and also accounting for gender differences in the female and male life expectancies as indicators of health performance.

Provided the role of education in livelihood sustainability, we conduct this study as one among many research works seeking to bring a solution to poor health problems in Africa, given the infectious diseases and epidemics with recent devastating health challenges of the cyclone in the southern African region, the Covid-19 unprecedented pandemic and the outbreak of the Ebola virus in the Congo Basins. The study employs the World Bank (2022) statistics to conduct this analysis while adopting the instrumental GMM strategy and the IV-2SLS strategy to address the problem of endogeneity. The findings of the study revealed that inclusive education is essential in improving health performance in Africa. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents brief theoretical underpinnings and empirical findings on the education-health performance nexus. The data and empirical methodology are presented in Sect. 3. Section 4 presents and discusses the findings whereas, in Sect. 5, we conclude with policy recommendations and further research perspectives.

2 Literature Review

Several findings have reported conflicting conclusions about educational differences in life expectancy and their effect on the wellbeing of individuals. According to Hendi (2017), these differences are partly due to the use of unreliable data to compute life expectancy and educational enrolment measures. Some studies employed life expectancy at birth as a measure of health performance (Hansen & Strulik, 2017; Hendi, 2017; Olshansky et al., 2012) while others adopt infant and child mortality as an indicator of health performance (Anyamele et al., 2017; Shapiro & Tenikue, 2017; Bado and Susuman, 2016).

Among studies that employed life expectancy as a health performance indicator is that of Hansen and Strulik (2017) who conducted a study in the United States of America and found that states with higher mortality rates from cardiovascular disease prior to the 1970s experienced increases in adult life expectancy and higher education enrollment. The findings of the study reveal that life expectancy increases with an increasing level of education from the primary to the tertiary education. Similarly, Olshansky et al. (2012) found out that in 2008, white men and women with more than 16 years of schooling had better life expectancies than citizens with fewer than 12 years of education. The results support the positive effect of education on health performance. Employing child survival indicator as a determinant of health performance, Mustafa and Odimegwu (2008) found out that the level of education and maternal awareness increase child survival in urban areas of Kenya, and is similarly to the findings of McTavish et al. (2010) who revealed that mothers in countries with higher literacy rates were more likely to use maternal health care and developed healthier habits which improve their health status than mothers with lower literacy rates.

In the same line of studies, another strand of literature emerged with authors adopting infant and child’s mortality as an indicator of health performance. Among these works are those conducted in Africa such as those of Anyamele et al. (2017) who examined the role of mother’s educational attainment in explaining infant and child mortality in Sub-Saharan Africa, Shapiro and Tenikue (2017) who established a relationship between education and child mortality in both rural and urban areas in Sub Saharan Africa. These authors found that there is a small variability in the risk of infant and child mortality attributable to country differences in Sub Saharan Africa. Their findings further reveal a statistically negative significant difference in infant and child mortality with urban dwellers compared to rural dwellers, showing that mother’s education negatively correlated with infant and child mortality. In both works conducted in Sub Saharan Africa, they argued that increased women’s schooling reduces infant mortality. In the advent of the Covid-19, Aristovnik et al. (2020) in establishing the effect of education on health vulnerabilities, revealed in his empirical work that people who attended higher education controlled the Covid-19 pandemic and were not affected as much as those who attended only the basic education.

Contrary to prior conclusions in the literature, Hendi (2017) conducted a study in the United States estimating life expectancy and lifespan variation by education using the American National Health Interview Survey and found out that life expectancy has either increased or decreased between 1990 and 2016 among all education-race groups except for non-Hispanic white women with less than a high school education who reside in the US. The author further reveals that there is an increase in life expectancy among white high school graduates and a smaller increase among black female high school graduates. Bado and Susuman (2016) conducted a study investigating the effect of education on the health performance of individuals in Sub Saharan Africa from 1990 to 2015. The authors found out that there is a significant decline in mortality among children of non-educated mothers compared to the decrease in mortality rates among children of educated mothers from 1990 to 2010 in Sub Saharan Africa. The findings also reveal that under-five mortality rates of children born to mothers without formal education are higher than the mortality rates of children of educated mothers. The authors concluded that the positive effect of education on health performance measured by under-five mortality as its inverse measure does not hold in Sub Saharan Africa between 1990 and 2015. Studies conducted in literature to investigate the health performance of individuals with differences in educational levels have provided mixed results, though attributed by Hendi (2017) to results from differences in the measure of health. Studies conducted in this regard did not consider inclusive education which accounts for both the male and the female educational enrolments. Similarly, these studies conducted on the effect of education on health performance have not considered the differences in the female and the male life expectancies which have been addressed in our study.

3 Data and Methodology

3.1 Data

The study investigates the effect of inclusive education on health performance inFootnote 148 Sub Saharan African countries from 2000 to 2020. The study employs secondary data obtained from the World Bank Development Indicators (2021). The sample size adopted, the number of countries selected and the time period of the study's investigation are constrained to limited data on inclusive education and the health performance indicators.

3.2 Presentation of Variables

-

The Dependent Variable

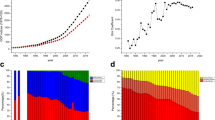

The study’s dependent variable is health performance measured by life expectancy at birth. The total life expectancy summarizes the mortality pattern that prevails across both genders and all age groups in a given year (World Bank, 2022). Also, the study employs the male life expectancy and the female life expectancy as dependent variables in the robustness analysis. Life expectancy indicates the expected years a newborn infant would live if prevailing patterns of mortality at the time of its birth were to stay the same throughout his or her life. Life expectancy is adopted in literature as a measure of health performance (Chen et al., 2021; Hansen & Strulik, 2017). Life expectancy is always higher in countries that invest more in the health sector (proper health care systems) than in countries whose health sectors’ are neglected (poor health facilities). An increase in life expectancy of a country signifies that the health performance of its citizens has improved while a decrease indicates a deterioration in health performance. The trends of the three health performance indicators employed in the study are presented in Fig. 1.

Figure 1 presents trends in health performance indicators. The total life expectancy increases from 52.52236 in 2000 to 63.28255 in 2020. The male life expectancy increases from 50.76683 in 2000 to 61.25102 in 2020 recording similar trends with the total life expectancy. The female life expectancy appears to be higher than the male life expectancy as it increases from 54.33012 in 2000 to 65.31148 in 2020. Figure 1 shows that the life expectancy in Sub Saharan African countries has increased over the years and according to the World Health Organization, this increase is due to increasing investments in the education and the health sectors.

-

Independent Variable of Interest

The main independent variable of interest isFootnote 2inclusive education. Following the contemporary and the non-contemporary literature, education enrolment is said to be inclusive if measured by a gender parity index (Okkolin et al., 2010; Ali, 2015; Asongu et al., 2020, 2021; World Bank, 2022). The study employed the primary, secondary and the tertiary enrolments all at gender parity indexes. Inclusive education is expected to be enhancing the life expectancy of citizens in Sub Saharan Africa. As a determinant of health performance, education is widely employed in literature (Hansen & Strulik, 2017; Anyamele et al., 2017; Shapiro & Tenikue, 2017; Bado and Susuman, 2016; Hendi, 2017). Figure 2 presents the evolution of inclusive education between 2000 and 2020.

Figure 2 presents trends in inclusive education within the period of the study. The figure shows that the rate of educational enrolments increases between 2000 and 2020. The enrolments rate of primary education increases from 0.8569636 in 2000 to 0.9962364 in 2020. The rate of secondary enrolments increases from 0.7735246 in 2000 to 1.006456 in 2020. The rate of tertiary enrolment has increased by a rate 0.36505 between 2000 (0.5832992) and 2020 (0.948253). Figure 3 presents scatter plots with an established correlation between inclusive education and life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa.

Figure 3 presents the correlation analysis between inclusive education and health performance in Sub Saharan Africa. Figure 3 presents a strong positive correlation between life expectancy and inclusive primary, secondary and tertiary enrolments. The first row of the figure presents the correlation of total life expectancy and educational enrolments, the second row presents the correlation between the female life expectancy and inclusive growth, and the third row presents the correlation between male life expectancy and inclusive growth. All the scatter plots indicate a positive correlation between inclusive education and life expectancy with the different genders taken into account. Figure 3 represents a preliminary analysis which presents the nature of the correlation between inclusive education and life expectancy. The correlation analysis’s results will be confirmed by a robust GMM results.

-

Control Variables

To account for other determinants that could influence the health performance of citizens in Sub Saharan African countries, we chose trade in services, employment in services, economic growth, domestic credit, gross savings and health expenditures as control variables of the study. Trade in services is expected to have a significant influence on health performance in Sub Saharan Africa. The inspiration to employ trade as a determinant of health performance is inspired by the works of Tahir (2020), Braine et al. (2020). The level of employment in services as a determinant of health performance is inspired from the works Assari (2018). Employment is expected to have positive effect on life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa if the salaries of employees are being paid but expected to be insignificant if there is loss of paid employment. The level of economic performance indicated by gross domestic product is expected to have a positive influence on the level of health performance if the growth in economic sector is transmitted to more investments in the health sector (Chen et al., 2021 and Kunze, 2014; He & Li, 2020). Domestic credit employed as an indicator of financial development and employed as a determinant of life expectancy is inspired by the works of Alam et al. (2021). Financial development is expected to have a significant influence on health performance. Savings can have both positive and negative influence on life expectancy depending on the fluctuations of the prices of accessing health services (Lien et al., 2021). Health expenditures as a determinant of life expectancy is expected to have a positive significant influence on health performance. Expenditure as a determinant of life expectancy is inspired from the works of Shahraki (2019) and Jakovljevic et al. (2016). The descriptive characteristics of all the variables in terms of their mean, standard deviation, their maximum and the minimum values are presented in Table 1 of descriptive statistics.

3.3 Methodology

The system GMM is adopted as a strategy to estimate the influence of inclusive education on health performance proxied by life expectancy at birth. The GMM addresses the potential problem of endogeneity through an instrumentation technique. This problem is addressed by accounting for the concern of reverse causality and time-invariant omitted variables (Nchofoung, 2022; Nchofoung & Asongu, 2022). The GMM technique is a robust technique that accounts for the error term related problems. The adoption of the system generalized method of moment technique in this study is based on the following justifications. (1) The number of cross-sections (48 countries) in the study should exceed the time series (21 years). The GMM technique produces unbiased results when the number of individuals is greater than the time duration. This is considered the main argument for the adoption of the GMM technique. (2) The study adopted a data set structured in a panel form for 48 African countries between 2000 and 2020. The GMM is a widely used strategy for panel analysis which takes care of cross-country variation since they are inherent in panel analyses (Baum et al., 2003; Kouladoum et al., 2022; Nchofoung & Asongu, 2022). (3) Thirdly, there is a high correlation between health performance variables and their first lags. The correlation between the total life expectancy and its first lag is 0.999, male life expectancy and its first lag is 0.992, and that of female life expectancy at birth and its first lag stands at 0.999. These higher correlations between life expectancy variables and their first lags which are all greater than the threshold of 0.800 considered an established rule of thumb for assessing the variable's persistence justified the adoption of the GMM technique (Asongu and Odhiambo, 2019).

The estimated equation with all the control variables is summarized as follows

where i and t represent individual cross sections and time respectively, HP signifies health performance, IE stands for inclusive education measured by captured by the gender parity school enrolments. Trade represents trade in services, emp signifies employment in services, savings represents domestic savings, HE stands for health expenditure, GDP and Intrepresent gross domestic product and the number of individuals using the internet with the the error term represented by ε.

The system GMM technique adopted in the study can be summarised with the equation in levels as follows

The model can be summarised with the equation in first difference as follows

where W is a vector of control variables. ηi is the country specific effect, γt is the time-specific constant, τ is the lagging coefficient and εit is the error term.

The problems usually associated with the GMM framework is the problem of weak identification, exclusion and simultaneity restrictions. To solve these problems, all explanatory variables are treated as exogenous with the time fixed effect used as instruments in the underlying regression (Stock and Wright, 2000; Kouladoum et al., 2022). In the context of the Two-step system GMM, the validity of over identifying restrictions are commonly tested via the J statistic of Hansen (1982). The J statics of Hansen represents the value of the GMM objective function that determines whether the GMM instrumental process is valid (Baum et al., 2003; Hill-Burns et al., 2017; Meghir et al., 2018) This is done under the following hypotheses:

where H0 represents the null hypothesis, E(zju) represents the Hansen J statistics under which instruments have to be validated for the model to be efficient. Following Baum et al. (2003) the Hansen j statistics has to be greater than 10% (Has to be insignificant) for the model validity.

Investigating the effect of inclusive education on the health performance suffices to derivate the health equation in 3 with respect to inclusive education to obtain the estimated effect of IE on HP.

The derivative equation of elasticity is given as

The coefficient \({\beta }_{1}\) represents the value at which health performance will vary if there is a 1% change in inclusive education. This value of the coefficient is determined in the GMM results presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5.

4 Results and Discussions

This section presents and discusses the findings of the study. The section begins with the presentation of the baseline results obtained by adopting the Driscoll/Kraay model. The Driscoll/Kraay strategy addresses the problem of cross-sectional dependence (Asongu & Nchofoung, 2021; Verma et al., 2022). The baseline results are presented in Table 2. The baseline results of the Driscoll/Kraay estimates do not accounts for the potential problem of endogeneity, heterogeneity and time variant effect. The highlighted estimation problems are addressed by the Generalized Method of Moment (GMM) technique in our study.The results of the GMM technique is presented in Tables 3, 4 and 5. The baseline results of the Driscoll/Kraay estimates indicate a positive effect of primary education on health performance. The secondary and the tertiary enrolment enhance life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa. The results of the baseline analysis will be further confirmed by a more robust GMM technique.

The conditions for the adoption of the GMM strategy hold in the study since it is a panel data analysis and the number of individual cross-Sects. (48 countries) is greater than the time series (21 years). Also, the condition of the role of thumb for the consistency of the dependent variables has been verified since the correlation between the dependent variables and their first lags are all greater than 0.800. The GMM findings presented in Table 3 are well estimated given that the Hansen probability values are all greater than 10%, prompting the rejection of weak identification of variables in Eq. 4. The nature of the Hansen probability validate the instruments used in the study. The results indicate that primary, secondary and tertiary enrolment enhances health expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa. The primary and the secondary enrolment enhances life expectancy at a 1% significance level while the tertiary education enhances life expectancy at a 10% statistical significance level. The results indicate that inclusive education measured by the gender parity index enhances health performance in Sub Saharan Africa. The results indicate that Africans live for long when they are educated with a better life expectancy. Inclusive education for all is considered one of the objectives in the African continent where the rate of school dropped out is very high due to early marriages for the male population and poverty in some rural areas. The findings on the positive effect of education on health performance are supported by those of Anyamele et al. (2017), Shapiro and Tenikue (2017), Bado and Susuman (2016) and Hendi (2017).

Controlling for other determinants of health, we employed trade in services, employment in services, GDP, internet, health expenditures and domestic savings as determinants of health performance. Trade-in services appeared to have a negative influence on the total life expectancy. Employment in service also has a negative impact on life expectancy within the period of the study. Gross savings have a positive effect on life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa. This signifies that the domestic savings enhance the health performance of citizens in these countries and is supported by the findings of Lien et al. (2021). The effect of health expenditure is not clear since the signs in different equations differ. As indicated in the first equation, health expenditure is likely to enhance health performance measured by life expectancy. This is so because healthcare expenditures are associated with an increase in health performance and a reduction in the number of infant and neonatal deaths (Jaba et al., 2014). Domestic credit has a significant positive effect on life expectancy which conforms with the findings of Alam et al. (2021). It signifies that the level of health performance is enhanced by increasing domestic credit to households in Sub Saharan African countries. Domestic credit helps to access household items to boost their wellbeing. ICT measured by the number of individuals using the internet shows that it enhances life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa which corroborates the findings of Lee et al. (2019). GDP has both a positive and a negative effect on life expectancy at birth. GDP can have a positive effect on health performance as in equation if the growth in the economic sector is transmitted also to the health sector. The level of economic development remains insignificant to the health sector if the growth is not transformed in the health sector to ameliorate the health performance and the life expectancy of the citizens.

4.1 Robustness Checks Accounting for Life Expectancies Across Different Genders

To test the consistency of our findings, the study employed life expectancy of the male and the female population as measures of health performance to determine whether the effect of inclusive education on health performance in Sub Saharan African countries varies across the male and the female genders. The robustness analysis is done by adopting a two-step system GMM. The results of the robustness checks are presented in Table 4 on the effect of inclusive education on health performance employing the male life expectancy and the female life expectancies.as indicators of health performance.

The findings presented in Table 4 indicate that the male life expectancy is enhanced by inclusive education both at the primary, secondary and at the tertiary level. The results also show that the primary and the secondary education have a more statistically significant influence on health performance than on the tertiary. The results also indicate a positive statistically significant effect of inclusive education on the female health performance. The primary and the tertiary enrolment both have positive significant effect on the female life expectancy in Sub Saharan Africa. The secondary enrolment still maintains a positive relationship with life expectancy, but appears to be insignificant. The robustness checks confirm the consistency of the study’s findings from the preliminary findings of the correlation analysis presented in Fig. 3 and the GMM analysis (Table3) when the total life expectancy is being employed as an indicator of health performance.

4.2 Robustness Checks with an Instrumental Two-Stage Least Square (IV-2SLS)

This section of the study employs the IV-2SLS strategy to test whether the GMM instrumental results are consistent. The 2SLS strategy addresses the feedback loops in the model to improve its efficiency. The IV-2SLS instrumentation process is validated by the Hansen and the Kleibergen tests (Baum et al., 2003 and Biørn, 2003). In our instrumentation process, we employ the control variables as endogenous and instrumental variables following the works of Hill-Burns et al. (2017). The Hansen test of over-identifying restrictions has to be insignificant for the rejection of the joint null hypothesis revealing valid instruments with uncorrelated residuals. Also, the Kleibergen P-values have to be significant to prompt the rejection of the null hypothesis (weakly identified) that can cause the results to be poorly estimated when instruments are weak.

The Hansen probability values are greater than 0.10 (insignificant) in all equations with normal distribution. The null hypothesis of equations exactly identified are not rejected and hence, we conclude that the 2SLS estimates are efficient. Similarly, all the Kleibergen P-values in all equations are significant, prompting the rejection of the null hypothesis of weak identification, validating the IV-2SLS strategy. The findings presented in Table 5 confirm the role of inclusive education in the improvement of health performance given that all the inclusive education indicators have positive statistically significant effects on health performance in Africa.

5 Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

The study investigated the impact of inclusive education on health performance in 48 Sub Saharan African countries from 2000 to 2020. The study adopted the Driscoll/Kraay estimator for its baseline analysis and the system GMM technique for its conclusive remarks. Inclusive education is measured in gender parity which encompasses both the male and the female genders. Inclusive education is measured at the primary, secondary and tertiary levels. The study employed the total life expectancy as an indicator of health performance. The results of the study reveal that inclusive education enhances life expectancy in Sub Saharan African countries. The robustness checks have been done by employing the male and the female life expectancy as indicators of health performance whose results are presented in Tables 4. The findings of the robustness checks reveal that inclusive education enhances both the male and the female life expectancy in these 48 Sub Saharan African countries. Also, the IV-2SLS strategy is adopted for further robustness checks to ensure that the GMM strategy provides consistent results. From the findings of the study, we can therefore conclude that inclusive education enhances health performance in Sub Saharan Africa. The findings of the study are supported by those of Bado and Susuman (2016), Anyamele et al. (2017) and Hendi (2017).

The study suggests policy orientate at enhancing the level of education in Sub Saharan Africa since it is the region with the highest illiteracy rate in the World. Policymakers are also called upon to invest more in the health sectors to make available health facilities that can help enhance the level of health performance in the region. As reported by the World Bank, there are a total of more than 30 million children in sub-Saharan Africa who do not attend school and also have a lower secondary completion rate. These recommendations are very important since African countries present higher infant mortality rates and lower life expectancy which all indicate poor health performance. The study does not provide the cases of individual Sub Saharan African countries and how education in these countries affects their life expectancy since it has been conducted in the whole region. For further perspectives, scientific works should be conducted to determine the effect of inclusive education on health performance by adopting other health indicators such as infant mortality rate in the case of individual African countries.

Notes

Angola, Benin, Botswana, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, Comoros, Congo, Dem. Rep, Congo, Republic, Cote d'Ivoire, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Eswatini, Ethiopia, Gabon, Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Lesotho, Liberia, Madagascar, Malawi, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Rwanda, Sao Tomel, Senegal, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Togo, Uganda, Zambia and Zimbabwe.

The inclusivity of education here is by considering gender equality in accessing education which indicates the parity between the different genders, computed as a quotient of the number of females by the number of males enrolled in different stages of education (World Bank glossary, 2022).

References

Alam, M. S., Islam, M. S., Shahzad, S. J. H., & Bilal, S. (2021). Rapid rise of life expectancy in Bangladesh: Does financial development matter? International Journal of Finance & Economics, 26(4), 4918–4931.

Ali, A. M. (2015). The level of teachers’ and students’ understanding and acceptability of inclusive education in public schools in Zanzibar (Doctoral dissertation, The Open University Of Tanzania).

Andersen, A., Fisker, A. B., Nielsen, S., Rodrigues, A., Benn, C. S., & Aaby, P. (2021). National immunization campaigns with oral polio vaccine may reduce all-cause mortality: An analysis of 13 years of demographic surveillance data from an urban African area. Clinical Infectious Diseases, 72(10), e596–e603.

Anyamele, O. D., Akanegbu, B. N., Assad, J. C., & Ukawuilulu, J. O. (2017). Differentials in infant and child mortality in Nigeria: Evidence from pooled 2003 and 2008 DHS data. Advances in Management and Applied Economics, 7(6), 73–96.

Aristovnik, A., Keržic, D., Ravšelj, D., Tomaževic, N., & Umek, L. (2020). A global student survey “Impacts of the covid-19 pandemic on life of higher education students” Methodological framework.

Asongu, S. A., Adegboye, A., Ejemeyovwi, J., & Umukoro, O. (2021). The mobile phone technology, gender inclusive education and public accountability in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy, 45(4), 102108.

Asongu, S. A., Nnanna, J., & Acha-Anyi, P. N. (2020). Finance, inequality and inclusive education in Sub-Saharan Africa. Economic Analysis and Policy, 67, 162–177.

Asongu, S., & Nchofoung, T. (2021). The terrorism-finance nexus contingent on globalisation and governance dynamics in Africa. European Xtramile Centre of African Studies WP/21/016.

Assari, S. (2018). Life expectancy gain due to employment status depends on race, gender, education, and their intersections. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities, 5(2), 375–386.

Bado, A. R., & Sathiya Susuman, A. (2016). Women's education and health inequalities in under-five mortality in selected sub-Saharan African countries, 1990–2015. Plos one, 11(7), e0159186.

Baum, J., & Wally, S. (2003). Strategic decision speed and firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24(11), 1107–1129.

Biørn, E., Hagen, T. P., Iversen, T., & Magnussen, J. (2003). The effect of activity-based financing on hospital efficiency: a panel data analysis of DEA efficiency scores 1992–2000. Health care management science, 6(4), 271–283.

Braine, T., Cervantes, R., Crisosto, N., Du, N., Kimes, S., Rosenberg, L. J., Rybka, G., Yang, J., Bowring, D., Chou, A. S., Khatiwada, R., Sonnenschein, A., Wester, W., Carosi, G., Woollett, N., Duffy, L. D., Bradley, R., Boutan, C., Jones, M., LaRoque, B. H., Oblath, N. S., Taubman, M. S., Clarke, J., Dove, A., Eddins, A., O'Kelley, S. R., Nawaz, S., Siddiqi, I., Stevenson, N., Agrawal, A., Dixit, A. V., Gleason, J. R., Jois, S., Sikivie, P., Solomon, J. A., Sullivan, N. S., Tanner, D. B., Lentz, E., Daw, E. J., Buckley, J. H., Harrington, P. M., Henriksen, E. A., Murch, K. W. & ADMX Collaboration. (2020). Extended search for the invisible axion with the axion dark matter experiment. Physical Review Letters, 124(10), 101303.

Byaro, M., Mayaya, H., & Pelizzo, R. (2022). Sustainable Development Goals for Sub-Saharan Africans’ by 2030: A Pathway to Longer Life Expectancy via Higher Health-Care Spending and Low Disease Burdens. African Journal of Economic Review, 10(2), 73–87.

Chen, W. L., Chen, Y. Y., Wu, W. T., Ho, C. L., & Wang, C. C. (2021). Life expectancy estimations and determinants of return to work among cancer survivors over a 7-year period. Scientific Reports, 11(1), 1–12.

Crawford, J., Butler-Henderson, K., Rudolph, J., Malkawi, B., Glowatz, M., Burton, R., & Lam, S. (2020). COVID-19: 20 countries’ higher education intra-period digital pedagogy responses. Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching, 3(1), 1–20.

Guisan, M. C., & Exposito, P. (2016). Life expectancy, education and development in African countries 1980-2014: Improvements and international comparisons. Applied Econometrics and International Development, 16(2), 87–108.

Hansen, C. W., & Strulik, H. (2017). Life expectancy and education: Evidence from the cardiovascular revolution. Journal of Economic Growth, 22(4), 421–450.

He, L., & Li, N. (2020). The linkages between life expectancy and economic growth: Some new evidence. Empirical Economics, 58(5), 2381–2402.

Hendi, A. S. (2017). Trends in education-specific life expectancy, data quality, and shifting education distributions: A note on recent research. Demography, 54(3), 1203–1213.

Hill-Burns, E. M., Debelius, J. W., Morton, J. T., Wissemann, W. T., Lewis, M. R., Wallen, Z. D., Peddada, S. D., Factor, S. A., Molho, E., Zabetian, C. P., Knight R., & Payami, H. (2017). Parkinson's disease and Parkinson's disease medications have distinct signatures of the gut microbiome. Movement Disorders, 32(5), 739–749.

Hoffman-Terry, M., Rhodes, L. V., & Reed, J. F. (1992). Impact of human immunodeficiency virus on medical and surgical residents. Archives of Internal Medicine, 152(9), 1788–1796.

Jaba, E., Balan, C. B., & Robu, I. B. (2014). The relationship between life expectancy at birth and health expenditures estimated by a cross-country and time-series analysis. Procedia Economics and Finance, 15, 108–114.

Jakovljevic, M. B., Vukovic, M., & Fontanesi, J. (2016). Life expectancy and health expenditure evolution in Eastern Europe—DiD and DEA analysis. Expert Review of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research, 16(4), 537–546.

Kouladoum, J. C., Wirajing, M. A. K., & Nchofoung, T. N. (2022). Digital technologies and financial inclusion in Sub-Saharan Africa. Telecommunications Policy, 1, 102387.

Kunze, L. (2014). Life expectancy and economic growth. Journal of Macroeconomics, 39, 54–65.

Lawal, Y. (2021). Africa’s low COVID-19 mortality rate: A paradox? International Journal of Infectious Diseases, 102, 118–122.

Lee, J. O., Choi, E., Shin, K. K., Hong, Y. H., Kim, H. G., Jeong, D., & Cho, J. Y. (2019). Compound K, a ginsenoside metabolite, plays an antiinflammatory role in macrophages by targeting the AKT1-mediated signaling pathway. Journal of Ginseng Research, 43(1), 154–160

Lien, W. C., Wang, W. M., Wang, F., & Wang, J. D. (2021). Savings of loss-of-life expectancy and lifetime medical costs from prevention of spinal cord injuries: Analysis of nationwide data followed for 17 years. Injury Prevention, 27(6), 567–573.

Luy, M., Zannella, M., Wegner-Siegmundt, C., Minagawa, Y., Lutz, W., & Caselli, G. (2019). The impact of increasing education levels on rising life expectancy: A decomposition analysis for Italy, Denmark, and the USA. Genus, 75(1), 1–21.

Martín Cervantes, P. A., Rueda López, N., & Cruz Rambaud, S. (2020). The relative importance of globalization and public expenditure on life expectancy in Europe: An approach based on MARS methodology. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(22), 8614.

McTavish, S., Moore, S., Harper, S., & Lynch, J. (2010). National female literacy, individual socio-economic status, and maternal health care use in sub-Saharan Africa. Social Science & Medicine, 71(11), 1958–1963.

Meara, E. R., Richards, S., & Cutler, D. M. (2008). The gap gets bigger: Changes in mortality and life expectancy, by education, 1981–2000. Health Affairs, 27(2), 350–360.

Mustafa, H. E., & Odimegwu, C. (2008). Socioeconomic determinants of infant mortality in Kenya: Analysis of Kenya DHS 2003. J Humanit Soc Sci, 2(8), 1934–2722.

Nchofoung, T. N. (2022). Trade shocks and labour market Resilience in Sub-Saharan Africa: Does the franc zone Response Differently? International Economics, 169, 161.

Nchofoung, T. N., & Asongu, S. A. (2022). Effects of infrastructures on environmental quality contingent on trade openness and governance dynamics in Africa. Renewable Energy, 189, 152–163.

Nchofoung, T. N., Asongu, S. A., Njamen Kengdo, A. A., & Achuo, E. D. (2022a). Linear and non-linear effects of infrastructures on inclusive human development in Africa. African Development Review, 34(1), 81–96.

Nchofoung, T., Asongu, S., & S Tchamyou, V. (2022b). Effect of women’s political inclusion on the level of infrastructures in Africa.

Okkolin, M. A., Lehtomäki, E., & Bhalalusesa, E. (2010). The successful education sector development in Tanzania–comment on gender balance and inclusive education. Gender and Education, 22(1), 63–71.

Okonji, E. F., Okonji, O. C., Mukumbang, F. C., & Van Wyk, B. (2021). Understanding varying COVID-19 mortality rates reported in Africa compared to Europe, Americas and Asia. Tropical Medicine & International Health, 26(7), 716–719.

Olshansky, S. J., Antonucci, T., Berkman, L., Binstock, R. H., Boersch-Supan, A., Cacioppo, J. T., & Rowe, J. (2012). Differences in life expectancy due to race and educational differences are widening, and many may not catch up. Health Affairs, 31(8), 1803–1813.

Saito, M. (2003). Amartya Sen’s capability approach to education: A critical exploration. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 37(1), 17–33.

Sen, A. (1999). Economics and health. The Lancet, 354, SIV20.

Shahraki, M. (2019). Public and private health expenditure and life expectancy in Iran. Payesh (health Monitor), 18(3), 221–230.

Shapiro, D., & Tenikue, M. (2017). Women’s education, infant and child mortality, and fertility decline in urban and rural sub-Saharan Africa. Demographic Research, 37, 669–708.

So, C., Kirby, K. A., Mehta, K., Hoffman, R. M., Powell, A. A., Freedland, S. J., & Walter, L. C. (2012). Medical center characteristics associated with PSA screening in elderly veterans with limited life expectancy. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 27(6), 653–660.

Susuman, A. S., Lougue, S., & Battala, M. (2016). Female literacy, fertility decline and life expectancy in Kerala, India: An analysis from Census of India 2011. Journal of Asian and African Studies, 51(1), 32–42.

Tahir, M. (2020). Trade and life expectancy in China: A cointegration analysis. China Economic Journal, 13(3), 322–338.

Talisuna, A. O., Okiro, E. A., Yahaya, A. A., Stephen, M., Bonkoungou, B., Musa, E. O., & Fall, I. S. (2020). Spatial and temporal distribution of infectious disease epidemics, disasters and other potential public health emergencies in the World Health Organisation Africa region, 2016–2018. Globalization and Health, 16(1), 1–12.

Tchamyou, V. S., Asongu, S. A., & Odhiambo, N. M. (2019). The role of ICT in modulating the effect of education and lifelong learning on income inequality and economic growth in Africa. African Development Review, 31(3), 261–274.

Tsui, J. I., Currie, S., Shen, H., Bini, E. J., Brau, N., & Wright, T. L. (2008). Treatment eligibility and outcomes in elderly patients with chronic hepatitis C: Results from the VA HCV-001 Study. Digestive Diseases and Sciences, 53(3), 809–814.

Verma, A., Giri, A. K., & Debata, B. (2022). Does ICT diffusion make human development sustainable in the era of globalization? An empirical analysis from SAARC economies.

World Bank. (2021). World development indicators 2021. The World Bank.

World Bank Glossary. (2022). https://databank.worldbank.org/metadataglossary/world-development-indicators/series/SP.DYN.LE00.IN

Zahid, M. N., & Perna, S. (2021). Continent-wide analysis of COVID 19: Total cases, deaths, tests, socio-economic, and morbidity factors associated to the mortality rate, and forecasting analysis in 2020–2021. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(10), 5350.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Kouladoum, JC. Inclusive Education and Health Performance in Sub Saharan Africa. Soc Indic Res 165, 879–900 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03046-w

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-03046-w