Abstract

This paper investigates inequality persistence in a group of 21 OECD countries using linear and non-linear fractionally integrated methods. Using linear models, the results show that the series are strongly persistent which implies lack of average reversal and permanency of shocks. Mean reversion is only found in the case of Finland and partial evidence of mean reversion is detected for Belgium, Greece, Austria and the Netherlands. The results are similar using non-linear methods. Mean reversion is only found in the case of Finland, Belgium, Greece and Spain. Although, most countries show no evidence of non-linear structures except for four countries, namely, Finland, Spain, the United Kingdom and the United States. The implications of the empirical findings are reported at the end of the manuscript.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Income inequality in many OECD members is at its peak for the last five decades. The richest 10% of the population in the income distribution possess about 50% of the entire wealth, while the bottom 40% hold just 3% of the total wealth (OECD, 2019). Moreover, the average income of the top 10% is around 900% of what the poorest 10% hold in the OECD countries, and the figure was just 700% about 25 years ago. In 2019–20, top earners were observed to earn more than eight times of what the bottom earners made (OECD, 2021). In 2021, about 25% of the OECD citizens believe that about 10% richest households earn more than 70% of the national income. In the same year, almost 80% of the OECD citizens believe that income inequalities are too conspicuous in their countries (OECD, 2021).

Consequently, the OECD has also recognised that economic insecurity involved a substantial section of the population. The living cost of the middle-class has risen quicker than inflation. The cost of housing has been increasing faster than household median income in these countries. About 30% are economically weak, suggesting they experience inadequate financial assets required to sustain a standard of living at the poverty level for a minimum of ninety days (OECD, 2019). On average, more than 20% of house renters in OECD countries experience some sorts of energy poverty (OECD, 2021b). Not surprisingly, reduction of inequality both within and among countries is one of the 17 goals recognised in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development (which was approved by the entire United Nation memberships in 2015). The United Nations (UN) Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) address several kinds of inequality in different contexts, ranging from the well-beings of individuals to global inequality to create conditions for sustainable, inclusive economic growth (Freistein & Mahlert, 2016; United Nations, 2015.)

Moreover, there are numerous papers on different dimensions of income inequality in OECD countries and elsewhere. For instance, there are studies on the causes as well as the consequences of income inequality (Ghoshray et al., 2020; Polacko, 2021). Income inequality has been linked to numerous negative outcomes. From an economic point of view, income inequality has been linked to reduced growth, investment and innovation. On the other hand, income inequality has been linked to health problems with negative physical and mental health outcomes that reduce life expectancy. Also, income inequality is related to social problems with a negative impact on key social areas such as crime, social mobility and education (Polacko, 2021).

An aspect of income inequality that has been predominantly disregarded in the present papers is the persistence of the series, which has numerous vital implications. Only a few papers have examined this nexus (Ghoshray et al., 2020; Gil-Alana et al., 2019; Islam & Madsen, 2015).

Persistence of income inequality implies that it would take longer for the series return to its long-run equilibrium after experiencing economic shock. Therefore, the magnitude of the income inequality’ persistence will determine how immense is the negative consequence of income inequality on the economy. Testing the persistence of income inequality also allows us to test the validity of Piketty hypothesis (Piketty & Saez, 2014). According to the hypothesis, an increase in inequality experienced in the recent times is a consequence of the stagnant economic growth being witnessed in several countries. Therefore, active interventions are needed to forestall the rising inequality. It has also been argued that being a bounded variable (because Gini coefficient, which is frequently used to depict income inequality, takes values between zero and one), income inequality should be stationary (Sanso-Navarro & Vera-Cabello, 2020). The fact that the income inequality series is persistent suggests that it will be tough to accurately project future trends of income inequality series based on its previous figures.

The purpose of the paper is to study the degree of persistence in income inequality in a group of 21 OECD countries during the period 1870–2020. To do this, we use the Gini index data since it is the most usually accepted inequality measure across the Globe (Charles et al., 2021). One of the contributions of this study is that we have concentrated on a subject matter that has not been adequately examined by the existing studies. Moreover, we have covered the longest dataset so far in the study of persistence of income inequality. By using up to fifteen decades of observations, the reliability of the results is enhanced and the persistence of convergence in income inequality can be evaluated over a long span horizon. Furthermore, we apply fractional integration methods. The fractional integration technique provides a more adequate approach to study persistence of the series because it allows degrees of differentiation which are less than or above 1, in contrast to other techniques or methods that use integer degrees of differentiation. In addition, we use both linear and non-linear models taking into account that the latter model is very much related with long memory issues.

This paper presents the following structure: Sect. 2 describes the literature review; Sect. 3 shows the methodology; Sect. 4 details the dataset; Sect. 5 summarises the main results and Sect. 6 provides some concluding remarks.

2 Literature Review

Income inequality has become a major challenge internationally with a significant impact on socioeconomic and political outcomes (Ferreira et al., 2022). There is an extensive literature on the causes and consequences of income inequality (Cohen & Ladaique, 2018; Ghoshray et al., 2020; Polacko, 2021). Some studies show that inequality is negatively linked with GDP growth (Banerjee & Duflo, 2003; Barro, 2000; Gil-Alana et al, 2019) and globalization (Banerjee, 2019; Galbraith & Choi, 2020). Others studies have shown that inequality is linked with technological change which will intensify the wage gap between unskilled and skilled workers: Acemoglu (2002), Autor et al. (2003), Violante (2008), Acemoglu and Author (2011), etc. On the other hand, inequality can be negatively related to financial stability (Tchamyou, 2021) and institutional and political factors such as labour market regulations and social security systems that can increase inequality (Coady & Dizioli, 2017; Holter, 2015; Koeniger et al., 2007). It has been argued that policy moves that intensify wealth and income inequality can also trigger more financial instability in an economy (Botta et al., 2021).

However, the literature on the persistence of income inequality is limited. Previous research on inequality persistence shows that inequality is highly persistent. Christopoulos and McAdam (2017) studied the persistence of the Gini coefficient in a panel of 47 nations during 1975–2013. These researchers show using unit root tests that the income inequality series were nonstationary, concluding that inequality measures are exceptionally persistent. Most recent studies like Gil-Alana et al. (2019) analysed persistence of income inequality for 26 OECD countries and its main determinants over the time period 1963–2008. The authors find a high persistence of income inequality in all the countries analyzed. Also, Ghoshray et al. (2020) showed a high persistence of inequality during the period from 1984 to 2013 for 60 countries. The authors proposed that the persistence of income inequality is structural in nature. In contrast, Islam and Madsen (2015) analyzed income inequality in 21 OECD countries during the period 1870–2011. These authors test Piketty's hypothesis to show that income inequality may increase in the twenty-first century but the impact of income inequality may be temporary.

Other studies show inconclusive results like Sanso-Navarro and Vera-Cabello (2020). They examined the Gini coefficient in developed economies during the period 1960–2017. These authors show that inequality has alternated between stationary and nonstationary series in most countries. Bandyopadhyay (2021) analyzed the fractional stochastic convergence of income in 16 Indian states over the period 1960–2019. This author shows that stochastic convergence is achieved by six states while the rest of states do not converge.

The persistent nature of inequality is considered one of the main challenges for the world economy because it can brake on economic growth and development. According to Ghoshray et al. (2020), the persistence of inequality hinders opportunities in education, investment in human capital and intergenerational and social mobility.

Recent studies such as Ferreira et al. (2022) show that nations with more income inequality have performed worse in facing the challenges of Covid-19 pandemic. In addition, these countries have a high percentage of their population living in precarious conditions. Given that the most vulnerable groups of the population have worse living conditions and higher health risks and risk of financial exposure (Loungani et al., 2021), income inequality can increase the negative impact of the COVID-19 pandemic (Oronce et al., 2020). In this context, Sayed and Peng (2021) argue that the COVID-19 pandemic has shown the high levels of health, social and economic inequality suffered by almost all societies. According to Moro et al. (2021), cities are facing increased segregation and inequality that can worsen the urban social fabric, negatively affecting people living in urban areas in relation to economic, social and health issues.

3 Methodology

Our paper is associated with the theoretical propositions of Durlauf (1996) that predicts that income inequality is likely to be persistent overtime. According to Durlauf (1996), income inequality is intergenerational as a result of certain assumptions. Education is assumed to locally financed in the economy. Also, an endogenous stratification of the economy is assumed to be existent in an economy. Endogenous stratification implies that the poor and rich reside in distinct communities, and while intra-community interaction is allowed inter-community interaction is not possible. Therefore, intercommunity borrowing is not possible. The consequence of the theory is that children or offspring of the rich are likely to remain rich as their parents, while children or offspring of the poor are likely to remain poor as their parents. Another consequence of the theory is that communities that are inhabited by the poor such as ghettos are likely to persist in the economy as the conditions that cause the existence of such communities are in the first place (such as insufficient human capital investment) are self-perpetuating.

We use linear and non-linear regression models within the fractional integration framework. In the linear case we consider the set-up proposed in Robinson (1994) and that is based on the following model,

where y(t) corresponds to the observed time series data, β and α are unknown coefficients associated to a linear time trend and a constant, and x(t) is an integrated of order d process, or I(d), so that u(t) is short-memory, i.e., an I(0) process. Thus, if d > 0, x(t) demonstrates the property of long memory, so named because of highly dependence of the observations. The determination of d is undertaken via the frequency domain version of an approximation to the likelihood function (Whittle function) by using a variant of a testing approach developed in Robinson (1994) for the linear case.

For the non-linear case we consider an extension of the above model by through Chebyshev polynomials in time of the form:

where T is sample size, and m is the Chebyshev polynomials order in time, which are expressed as:

These polynomials are well described in Hamming (1973) and Smyth (1998), and Bierens (1997), Tomasevic et al. (2009) and others have pointed out that it is possible to estimate highly non-linear trends with rather low degree polynomials. The model presented in (2) along with an I (d) process for x (t) was employed by Cuestas and Gil-Alana (2016) extending the approach in Robinson (1994) to the non-linear case, and this is the approach employed in the present paper. Note that m = 1 if the model involves only a constant; m = 2, if it involves both a constant as well as a linear trend as in Eq. (1), and m > 2 if non-linearities are involved with greater m indicating a bigger level of non-linearity. In the empirical investigation conducted in Sect. 5 we set m = 4, and thus θ3 and θ4 are the coefficients capturing possible non-linearities in the data.

4 Data

The data have been provided by Solt (2020)0.1Footnote 1 The range of the index is 0–100 with the higher values denoting larger income inequality. The annual data series analyzed start from 1870 and end in 2016 (Japan), in 2018 (Austria, Australia, Belgium, France, Greece, Germany, New Zeeland, Portugal, Sweden, Spain and Switzerland), in 2019 (Canada, Denmark, Finland, Ireland, Italy, Netherlands and Norway) and for the UK in 2020 (see, Table 1).

The Gini indices of all the series analyzed take values between 18.3 (Spain, 1945) and 80.4 (Finland, 1886).The maximum and minimum values of all countries present a great dispersion since the former can take values between 35.3 and 80.4 and the latter between 18.3 and 28.7. Finland, the Netherlands and Switzerland with standard deviations of 17.7, 15.7 and 13.7, respectively, are the countries with the most heterogeneous distributions in the study period.

Figure 1 shows the average Gini index per year for each of the countries analyzed. Most countries show an average value lower or very close to the global average Gini Index. This is not the case for Finland, Italy, the Netherlands and Switzerland. All of these present mean values higher than 33.6 (global average Gini index).

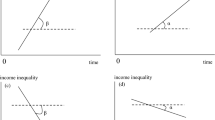

In general, all the series show a decrease (more or less fast) in the Gini Index during the period under consideration (Fig. 2). Furthermore, the series show a slight growth from 1980 and converge towards mean values of inequality comprised in the interval (26–39).

The decrease of the Gini index is shown in Fig. 3. All countries show a decline in inequality when comparing the Gini index of 2018 with the index in 1870. Only Spain and Portugal show an increase by 4 and 3 points respectively.

Some studies such as Malla and Patrianakos (2022) have shown that fiscal policy is an important instrument to reduce inequality and poverty. In this context, the Gini index after taxes and transfers, for each of the countries considered, is lower than the Gini index before taxes and transfers. We find evidence that fiscal policy has played an important role in reducing inequality, especially in advanced economies where there was high income inequality before taxes and transfers. Furthermore, studies like Coady and Gupta (2012) reveal that fiscal policy reduced the Gini index of 25 OECD countries by almost a third in the period 1985- 2005. Also, we find in the literature that transfers and taxes reduced inequality and poverty in the period 2003–2012 (CEPAL & IEF, 2014).

5 Empirical Results

5.1 Linear Case

We commence by presenting the empirical results of the linear model as described by Eq. (1), first with the supposition that u (t) has a white noise format. We report in Table 2 the estimates of d (and the 95% confidence intervals) under the three standard scenarios of i) no terms (results reported in column 2), ii) with an intercept (column 3), and iii) with an intercept as well as a linear time trend (column 4), reporting in bold in the table the model chosen for each country.

We first observe that the time trend is required in a number of cases, in particular, for Austria, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway and Switzerland. Table 3 displays the estimated coefficients and we observe that the time trend is significantly negative in the six countries, the highest coefficients (in absolute value) observed in Finland (− 0.345) and Switzerland (− 0.259). Considering the estimated values of the differencing parameter d (and the 95% confidence bands) we see that the values are high and close to 1 in the most of the cases; however, statistical support for mean reversion is only found in three countries: Greece (with an estimated value of d equal to 0.92), Belgium (d = 0.81) and particularly Finland (0.68). Note that in these three cases the values in the confidence intervals exclude the value of 1. On the other extreme, for two nations the estimates of d are considerably greater than 1: Italy (d = 1.12) and Denmark (1.23) (in these cases the values in the intervals are also strictly higher than 1), while for the remaining countries the unit root null hypothesis (i.e., d = 1) cannot be rejected.

Allowing serial correlation throughout the model of Bloomfield (1973), the empirical results are reported across Tables 4 and 5. In Table 4 we display the values of d as in Table 2 but imposing weak autocorrelation for the error term, i.e. for u (t) in (1). However, instead of using a parametric ARMA structure we use a non-parametric approach due to Bloomfield (1973) that approximates this class of models. The time trend is now significant in 13 out of the 21 countries investigated, and the highest coefficients correspond once more to Finland (− 0.346) and Switzerland (− 0.246) along with the Netherlands (− 0.317). The estimates of d (and their confidence intervals) are now slightly smaller than in the previous case and mean reversion is noticed in Austria (0.58), Finland (0.68) and the Netherlands (0.76), while the I(1) hypothesis cannot be rejected in the rest of the cases.

According to the results presented so far, Finland is the only country displaying mean reversion under the two scenarios of white noise and autocorrelated errors, and partial mean reversion evidence is also detected in Belgium and Greece (under the assumption of white noise errors) and in Austria and the Netherlands under autocorrelation of the form of Bloomfield (1973). For the rest of the countries, the estimates of d have a minimum value of 1, implying then that under this linear set-up shocks are expected to be permanent, persisting forever.

5.2 5b. Non-Linear Case

Using the model given by Eq. (2), based on the Chebyshev polynomials in time and using the methodology developed in Cuestas and Gil-Alana (2016), the results are reported in Table 6. Focussing first on the estimates of the differencing parameter, d, we observe that only four countries display a mean reverting (d < 1) pattern: Finland (with an estimated value of d equal to 0.55), Belgium and Greece (with a value of d of 0.80) and Spain (0.86). However, the evidence of non-linear structures is very limited. Thus, only Finland, Spain, the UK, and particularly, the US are the only countries showing some evidence of non-linear structures,

Our results are in line with the predictions of the theoretical propositions of Durlauf (1996) that state that income inequality is likely to be persistent. Our results are also consistent with the previous studies on the existence of persistence in income inequality in most countries (Christopoulos & McAdam, 2017; Ghoshray et al., 2020; Gil-Alana et al., 2019; etc.). The results of the linear model under the assumption of white noise errors and under the assumption of autocorrelation as well as the results of the few countries that show evidence of non-linear structures, confirm the persistence of inequality in most the series analyzed.

One of the possible rationales behind the observed empirical findings of persistence of income inequality is the persistence of macroeconomic series in advanced countries, particularly the persistence of GDP. Persistence in GDP generates persistence in other series that are affected by changes in GDP including income inequality. Rapach (2002) has shown that GDP is persistent in advanced economies. Garcia-Penalosa and Turnovsky (2006) has demonstrated that an economy experiencing greater economic growth will witness higher income inequality than before. According to Hendry and Juselius (2000), a series that is dependent on another series which is persistent will inherit such persistence, and spread it to several other series in the country.

6 Concluding comments

This paper deals with the analysis of inequality persistence in a group of 21 OECD countries using linear and non-linear fractionally integrated methods. Starting with the linear models, the results indicate that the time trend is needed in only few cases, particularly for Austria, Belgium, Finland, Greece, Norway and Switzerland under white noise errors, and in a few countries more under autocorrelated disturbances, in all cases with negative coefficients for the time trend. Dealing with the degree of persistence, evidence of mean reversion, that is, estimates of d considerably less than 1, is only obtained for Finland under the two scenarios of white noise and autocorrelated errors, and partial evidence of mean reversion is also detected in Belgium, Greece, Austria and the Netherlands under one of the two scenarios. In the rest of the countries, the estimates of d have a minimum value of 1, denoting lack of mean reversion and durability of shocks. Allowing non-linear deterministic terms through the Chebyshev polynomials in time, four countries display mean reversion: Finland, Belgium, Greece and Spain, while Finland, Spain, the UK and the US are the only countries showing some evidence of non-linear structures.

One of the implications of the results is that the validity of the Piketty hypothesis is invalid in most of the OECD countries. Therefore, there is a need for a mixture of long-term structural policies to deal with inequality in countries with non-stationary series. Failure to act in a robust manner might lead to the continuation of income inequality in the OECD countries and its attendant effect. Periodic increase in minimum wages, increase in access to high-quality education to the general public, improve retirement security. While there is no silver bullet to instantaneously swing decades-long trends in increasing income inequality, these policies can foster an economy that works for all. For countries with these income inequality-reducing policies, additional blueprints can be introduced because this means that the existing policies are insufficient. Since the results also suggest less evidence for non-linear structures, there is a prompt need to introduce all the relevant to address income inequality.

For countries with stationary income inequality such as Finland, Belgium and Greece, robust monetary policies can be introduced to improve income distribution. However, the direction of monetary policy depends on the situation on ground. Under the assumption that bottom income group relying principally on labour earnings hold more liquid assets than top income group, contractionary monetary policy should be implemented. On the other hand, expansionary monetary policy can be implemented if most of the borrowers in the economy are less wealthy. This is because unexpected decrease in policy rates (which is an element of monetary policy) will benefit borrowers in the economy.

One of the implications of the results is that developing countries are expected to be more inward-looking when attempting to solve inequality in their countries. This is because inequality in developed countries is serious and these developed countries should prioritise their own countries first before thinking of how to help address income inequality in the developing countries. There is a need for welfare-improving policies targeting communities where the poor reside in order for income inequality of a developing country to be effectively tackled. These policies include improvement in creating or improving child benefit systems, universal tax credit mechanism, national minimum wage and subsidies for education and health care.

One of the limitations of the present work is its univariate nature. Multivariate models including, for example, exogenous regressors in the linear and non-linear models is a line of research that should be further investigated. In this context, fractional cointegration seems to be another area of methodological research, using for example, the fractional CVAR (FCVAR) model described in Johansen and Nielsen (2010, 2012). Work in this direction is now in progress.

Notes

1 The author, using cross-validation and taking as a reference the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS), indicates that the estimates of the new Standardized Word Income Inequality Database (SWIID) are more accurate than in previous versions. Therefore, it concludes that SWII provides optimal data for research on income inequality measured in terms of the Gini Index.

References

Acemoglu, D. (2002). Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. Journal of Economic Literature, 40(1), 7–72.

Acemoglu D., Autor D., (2011) Skills, tasks and technologies: Implica-tions for employment and earnings. In: En D Card, y O Ashenfelter (eds), Handbook of Labor Economics. Elsevier:Amsterdam. pp 1043-1171.

Autor, D. H., Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (2003). The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118(4), 1279–1333.

Bandyopadhyay, S. (2021). The persistence of inequality across Indian states: a time series approach. Review of Development Economics, 25(3), 1150–1171.

Banerjee, A. K. (2019). Measuring multidimensional inequality: a Gini index. The globalization conundrum—dark clouds behind the silver lining (pp. 65–78). Singapore: Springer.

Banerjee, A. V., & Duflo, E. (2003). Inequality and growth: What can the data say? Journal of Economic Growth, 8(3), 267–299.

Barro, R. (2000). Inequality and Growth in a Panel of Countries. Journal of Economic Growth., 5, 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1009850119329

Bierens, H. J. (1997). Testing the unit root with drift hypothesis against nonlinear trend stationarity, with an application to the u.s. price level and interest rate. Journal of Econometrics, 81(1), 29–64.

Bloomfield, P. (1973). An exponential model for the spectrum of a scalar time series. Biometrika, 60(2), 217–226.

Botta, A., Caverzasi, E., Russo, A., Gallegati, M., & Stiglitz, J. E. (2021). Inequality and finance in a rent economy. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 183, 998–1029.

CEPAL & IEF (2014). Los efectos de la política fiscal sobre la redistribución en Américas Latina y la Unión Europea. Colección Estudios n 8.

Charles, V., Gherman, T., & Paliza, J. C. (2021). The Gini Index: a modern measure of inequality. In V. Charles & A. Emrouznejad (Eds.), modern indices for international economic diplomacy. Palgrave Macmilan: International Political Economy Series.

Christopoulos, D., & McAdam, P. (2017). On the persistence of cross-country inequality measures. Journal of Money, Credit and Banking, 49(1), 255–266.

Coady, D., & Dizioli, A. (2017). Income inequality and education revisited: persistence, endogeneity and heterogeneity. Applied Economics., 50, 1–15.

Coady, D., & Gupta, S. (2012). Income inequality and fiscal policy (2nd ed.). Washington: International Monetary Fund.

Cohen, G., & Ladaique, M. (2018). Drivers of growing income inequalities in OECD and European countries. In R. M. Carmo, C. Rio, & M. Medgyesi (Eds.), Reducing inequalities (pp. 31–43). Palgrave Macmillan.

Cuestas, J. C., & Gil-Alana, L. A. (2016). A nonlinear approach with long range dependence based on Chebyshev polynomials. Studies in Nonlinear Dynamics and Econometrics, 20, 57–94.

Durlauf, S. N. (1996). A theory of persistent income inequality. Journal of Economic Growth, 1(1), 75–93.

Ferreira, I. A., Gisselquist, R. M., & Tarp, F. (2022). On the impact of inequality on growth, human development, and governance. International Studies Review. https://doi.org/10.1093/isr/viab058

Freistein, K., & Mahlert, B. (2016). The potential for tackling inequality in the Sustainable Development Goals. Third World Quarterly, 37(12), 2139–2155.

Galbraith, J. K., & Choi, J. (2020). Inequality under globalization: State of knowledge and implications for economics. In E. Webster, I. Valodia, & D. Francis (Eds.), Inequality studies from the Global South (chapter 3). London: Routledge.

Garcia-Penalosa, C., & Turnovsky, S. J. (2006). Growth and income inequality: a canonical model. Economic Theory, 28(1), 25–49.

Ghoshray, A., Monfort, M., & Ordóñez, J. (2020). Re-examining inequality persistence. Economics: the open-access. Open-Assessment E- Journal, 14, 1–9.

Gil-Alana, L. A., Škare, M., & Pržiklas-Družeta, R. (2019). Measuring inequality persistence in OECD 1963–2008 using fractional integration and cointegration. The Quarterly Review of Economics and Finance, 72, 65–72.

Hamming, R. W. (1973). Numerical methods for scientists and engineers. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications.

Hendry, D. F., & Juselius, K. (2000). Explaining cointegration analysis: part 1. The Energy Journal, 21(1), 1–42.

Holter, H. A. (2015). Accounting for cross-country differences in intergenerational earnings persistence: The impact of taxation and public education expenditure. Quantitative Economics, 6(2), 385–428.

Johansen, S., & Nielsen, M. Ø. (2010). Likelihood inference for a nonstationary fractional autoregressive model. Journal of Econometrics, 158, 51–66.

Johansen, S., & Nielsen, M. Ø. (2012). Likelihood inference for a fractionally cointegrated vector autoregressive model. Econometrica, 80, 2667–2732.

Koeniger, W., Leonardi, M., & Nunziata, L. (2007). Labor market institutions and wage inequality. ILR Review, 60(3), 340–356.

Loungani, P., Ostry, J., Furceri, D., & Pizzuto, P. (2021). Will COVID-19 Have long-lasting effects on inequality? Evidence from past pandemics. IMF Working Papers, 2021(127), 1. https://doi.org/10.5089/9781513582375.001

Malla, M. H., & Patrianakos, P. (2022). Fiscal policy and income inequality: the critical role of institutional capacity. Economies, 10(5), 115.

Moro, E., Calacci, D., Dong, X., & Pentland, A. (2021). Mobility patterns are associated with experienced income segregation in large US cities. Nature Communications, 12(1), 1–10.

OECD (2019), Under pressure: the squeezed middle class, oecd publishing, paris. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/689afed1-en Accessed on 28/10/2021

OECD (2021). Does Inequality Matter? How people perceive economic disparities and social mobility. OECD Publishing, Paris, Available at: https://doi.org/10.1787/3023ed40-en. Accessed on 27/06/2022.

Oronce, C. I. A., Scannell, C. A., Kawachi, I., & Tsugawa, Y. (2020). Association between state-level income inequality and COVID-19 cases and mortality in the USA. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 35(9), 2791–2793.

Piketty, T., & Saez, E. (2014). Inequality in the long run. Science, 344(6186), 838–843.

Polacko, M. (2021). Causes and consequences of income inequality – an overview. Statistics, Politics and Policy, 12(2), 341–357.

Rabiul Islam, Md., & Madsen, J. B. (2015). Is income inequality persistent? Evidence using panel stationarity tests, 1870–2011. Economics Letters, 127, 17–19. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2014.12.024

Rapach, D. E. (2002). The long-run relationship between inflation and real stock prices. Journal of Macroeconomics, 24(3), 331–351.

Robinson, P. M. (1994). Efficient tests of nonstationary hypotheses. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 89, 1420–1437.

Sanso-Navarro, M., & Vera-Cabello, M. (2020). Income inequality and persistence changes. Social Indicators Research, 152, 495–511.

Sayed, A., & Peng, B. (2021). Pandemics and income inequality: a historical review. SN Business & Economics, 1(4), 1–17.

Smyth, G. K. (1998). Polynomial Aproximation. Chichesters: Wiley.

Solt, F. (2020). Measuring income inequality across countries and over time: the standardized world income inequality database. Social Science Quarterly, 101(3), 1183–1199.

Tchamyou, V. S. (2021). Financial access, governance and the persistence of inequality in Africa: mechanisms and policy instruments. Journal of Public Affairs, 21(2), e2201.

Tomasevic, N., Tomasevic, M., & Stanivuk, T. (2009). Regression analysis and approximation by means of chebyshev polynomial. Informatologia, 42(3), 166–172.

United Nations (2015). Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development A/RES/70/1

Violante, G. L. (2008). Skill-biased technical change. In L. Blume & S. Durlauf (Eds.), The new Palgrave dictionary of economics. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Wildman, J. (2021). COVID-19 and income inequality in OECD countries. The European Journal of Health Economics, 22(3), 455–462.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Solarin, S.A., Lafuente, C., Gil-Alana, L.A. et al. Inequality Persistence of 21 OECD Countries from 1870 to 2020: Linear and Non-Linear Fractional Integration Approaches. Soc Indic Res 164, 711–725 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02982-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-022-02982-x