Abstract

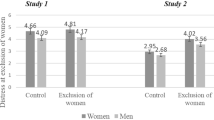

Williams and Sommer found that ostracized women, but not men, worked harder on a subsequent collective task, speculating that women’s social compensation was motivated by threatened belongingness. The present 2 × 3 design with 180 U.S. women and men replicated this gender gap in work contributions then closed it using two status-manipulations that favored women’s task abilities or the higher education of undergraduates with high school partners. Additional analyses identified three clusters of participants who failed to compensate: only men in the replication control, women scoring low in self-monitoring, and participants who persisted unsuccessfully to resist exclusion. These patterns shift our focus away from gender and threatened belongingness toward control and status as explanations for the original gender difference.

Similar content being viewed by others

References

Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529.

Berger, J., Ridgeway, C. L., & Zelditch, M. (2002). Construction of status and referential structures. Sociological Theory, 20, 157–179.

Carroll, M. P. (1998). But fingerprints don’t lie, eh?: Prevailing gender ideologies and scientific knowledge. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 22, 739–749.

Chodorow, N. (1978). The reproduction of mothering. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Cohen, E. G., & Lotan, R. A. (1995). Producing equal-status interaction in the heterogeneous classroom. American Educational Research Journal, 32, 99–120.

Eagly, A. H., & Mladinic, A. (1989). Gender stereotypes and attitudes toward women and men. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 15, 543–558.

Fiske, S. T., Cuddy, A. J. C., Glick, P., & Xu, J. (2002). A model of (often mixed) stereotype content: Competence and warmth respectively follow from perceived status and competition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 878–902.

Frazier, R. B., & Fatis, M. (1980). Sex differences in self-monitoring. Psychological Reports, 47, 597–598.

Gangestad, S. W., & Snyder, M. (2000). Self-monitoring: Appraisal and reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 126, 530–555.

Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Cambridge, MA: Harvard.

Glick, P., & Fiske, S. T. (2001). An ambivalent alliance: Hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. American Psychologist, 56, 109–118.

Hare-Mustin, R. T., & Marecek, J. (1988). The meaning of difference: Gender theory, postmodernism, and psychology. American Psychologist, 43, 455–464.

Hogue, M., & Yoder, J. D. (2003). The role of status in producing depressed entitlement in women’s and men’s pay allocations. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27, 330–337.

Hyde, J. S. (2005). The gender similarities hypothesis. American Psychologist, 60, 581–592.

Johnson, C., & Ford, R. (1986). Dependence, power, legitimacy, and tactical choice. Social Psychology Quarterly, 59, 126–139.

Kasof, J. (1993). Sex bias in the names of stimulus persons. Psychological Bulletin, 113, 140–163.

Kerber, L. K. (1986). Some cautionary words for historians. Signs, 11, 304–310.

LaFrance, M., Paluck, E. L., & Brescoll, V. (2004). Sex changes: A current perspective on the psychology of gender. In A. H. Eagly, A. E. Beall, & R. J. Sternberg (Eds.), The psychology of gender (2nd ed.). (pp. 328–344). New York: Guilford.

Latané, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences of social loafing. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 37, 822–832.

Miller, J. B. (1976). Toward a new psychology of women. Boston, MA: Beacon Press.

Philipp, S. F. (1998). Race and gender differences in adolescent peer group approval of leisure activities. Journal of Leisure Research, 30, 214–232.

Reis, H. T., Senchak, M., & Solomon, B. (1985). Sex differences in the intimacy of social interaction: Further examination of potential explanations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 48, 1204–1217.

Ridgeway, C. (1991). The social construction of status value: Gender and other nominal characteristics. Social Forces, 70, 367–386.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Smith-Lovin, L. (1999). The gender system and interaction. Annual Review of Sociology, 25, 191–216.

Ridgeway, C. L., & Walker, H. A. (2001). Status structures. In A. Branaman (Ed.), Self and society (pp. 298–320). Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Snyder, M., & Gangestad, S. (1986). On the nature of self-monitoring: Matters of assessment, matters of validity. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 125–139.

Steele, C. M. (1997). A threat in the air: How stereotypes shape intellectual identity and performance. American Psychologist, 52, 613–629.

Swim, J. K. (1994). Perceived versus meta-analytic effect sizes: An assessment of the accuracy of gender stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 66, 21–36.

Tyler, T. R., & Blader, L. (2002). Autonomous vs. comparative status: Must we be better than others to feel good about ourselves? Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 89, 813–838.

Williams, K. D. (2001). Ostracism: The power of silence. New York: Guilford.

Williams, K. D., Cheung, C. K. T., & Choi, W. (2000). Cyberostracism: Effects of being ignored over the Internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 748–762.

Williams, K. D., Govan, C. L., Croker, V., Tynan, D., Cruickshank, M., & Lam, A. (2002). Investigations into differences between social- and cyberostracism. Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice, 6, 65–77.

Williams, K. D., & Karau, J. (1991). Social loafing and social compensation: The effects of expectations of co-worker performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 61, 570–581.

Williams, K. D., Karau, S. J., & Bourgeois, M. J. (1993). Working on collective tasks: Social loafing and social compensation. In M. A. Hogg & D. Abrams (Eds.), Group motivation: Social psychological perspectives (pp. 130–148). Hertfordshire, England: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Williams, K. D., & Sommer, K. L. (1997). Social ostracism by coworkers: Does rejection lead to loafing or compensation? Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 23, 693–706.

Yoder, J. D., & Kahn, A. S. (1993). Working toward an inclusive psychology of women. American Psychologist, 48, 846–850.

Yoder, J. D., & Kahn, A. S. (2003). Making gender comparisons more meaningful: A call for more attention to social context. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 27, 281–290.

Zadro, L., Williams, K. D., & Richardson, R. (2004). How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 40, 560–567.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

The authors thank Kipling Williams and Kristin Sommer for sharing their materials including the cyberball game; Mark Snyder for permission to use the self-monitoring scale; and Arnie Kahn for his supportive and helpful comments. We also appreciate the invaluable help of John Bean, Jessica Christopher, John Haller, David Monter, Pamela Ruesch, and Angela Saniat who, like the first author, served as experimenters throughout data collection.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bozin, M.A., Yoder, J.D. Social Status, Not Gender Alone, Is Implicated in Different Reactions By Women and Men to Social Ostracism. Sex Roles 58, 713–720 (2008). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9383-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-007-9383-1