Abstract

Entrepreneurs can benefit from the communities they build. Therefore, many entrepreneurs create online communities that allow self-selected stakeholders, such as customers, crowd investors, or enthusiasts, to interact with the venture and other like-minded individuals. However, research on how entrepreneurs can successfully engage community members and grow such online communities is only slowly emerging. In particular, it is unclear if, how much, and which content entrepreneurs should contribute to foster engagement in different types of communities and which role these community types play in the community’s overall growth. Based on a longitudinal case study in the video game industry, we first theorize and show that—depending on the community type—both too much and too little entrepreneur-provided content fails to leverage community engagement potential and that different communities require more or less diverging content. We then theorize and show that community growth is largely driven by engagement in open communities, such as those hosted on social media. We outline the implications this has for entrepreneurs, our understanding of online communities, and entrepreneurial communities more generally.

Plain English Summary

How can entrepreneurs engage and grow different types of online communities?

Managing online communities is crucial for many entrepreneurs. However, different community types, open and core, play different roles and require different content and growth strategies. Core communities, such as those hosted on online forums, respond well to less but more diverse content, whereas open communities on social media drive overall community growth with more but less diverse content. Entrepreneurs need to find the right balance and pay attention to the tipping point of content provision, as too much content might endanger community member engagement. By understanding the dynamics of online communities, entrepreneurs can effectively nurture engagement and optimize their efforts for long-term success. Investing resources wisely in content production, considering the costs involved, can be beneficial for new ventures seeking sustainable community growth.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

Social networks provide entrepreneurs with access to advice, feedback, and ideas while also granting them the opportunity to reach new customers and investors (Cornelius & Gokpinar, 2020; Hayter, 2013; Lin & Maruping, 2022; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Online communication allows entrepreneurs and community members to engage in such networks without space and time constraints (e.g., Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017). Online communities—which are “[i]nternet-based platforms for communication and exchange among individuals and entities with shared interests” (Fisher, 2019, p. 281)—have therefore become a valuable resource for the growth and success of entrepreneurial ventures (Hertel et al., 2021; Lin & Maruping, 2022). Entrepreneurs might either participate in existing online communities to exchange, for example, with other entrepreneurs (e.g., Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017; Lall et al., 2022; Meurer et al., 2022; Schou et al., 2022; Vaast, 2023), or they may create and foster their own online communities, hosting, for example, crowd investors, product users, and brand evangelists (e.g., Allison et al., 2017; Block et al., 2018, 2021; Fisher, 2019; Hampel et al., 2020). In particular, those communities focused on salient characteristics of a product or service can be a centerpiece of an entrepreneurial venture’s business model (e.g., Nambisan, 2017; Tschang, 2021).

However, hosting an online community for crowd investors, brand evangelists, and other similar stakeholders can be challenging. Engagement in the community can be low, and membership in the community is often temporary and fluent (Gibson et al., 2021). Entrepreneurs, therefore, need to actively foster engagement and community growth (Glozer et al., 2019; Hampel et al., 2020; Loh & Kretschmer, 2023; Wang et al., 2013). Currently, our understanding of how entrepreneurs can engage and grow their online communities is slowly emerging. Previous research highlights the importance of basic strategies for member engagement (e.g., Castelló et al., 2016; Miller et al., 2009), the design of digital platforms (e.g., Hsieh & Vergne, 2023; Ren et al., 2012; West & O'Mahony, 2008), the language entrepreneurs use (Seigner et al., 2023), and the governance of interactions among members (e.g., He et al., 2020; Piezunka & Dahlander, 2019; Reischauer & Mair, 2018). While this emerging literature is instrumental for developing theory on online community management, it has several key gaps. One gap is that while research has acknowledged the diversity of online communities (e.g., Murray et al., 2020; Schou et al., 2022), it has thus far not fleshed out what this diversity specifically implies. A second gap is that there are still few ideas in the literature about what entrepreneurs can do to foster engagement and growth, including which and how much input they should provide (Glozer et al., 2019; Reischauer & Mair, 2018; Seigner et al., 2023). Addressing these gaps is important, as entrepreneurs who want to host their online communities often use different communication platforms that address different audiences and face decisions daily on how much input each community needs and which type of input would be most effective on which platform (Culnan & McHugh, 2010; Hanna et al., 2011).

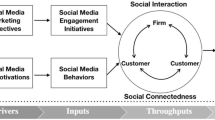

In the following study, we address those two gaps. We distinguish between two types of digital platforms entrepreneurs can use to host their own online communities, which previous research called private-closed and public-open platforms (Dobusch et al., 2019; Heavey et al., 2020). Private-closed platforms, such as dedicated internet forums, require a specific sign-up and might have a gatekeeper maintaining community boundaries. Those communities tend to attract a dedicated core audience invested in the specific firm, product, or service. We call such communities core communities. Public-open platforms, such as groups on traditional social media, do not require a specific sign-up and are thus open and fluent. They attract a wider, more casual audience, which is why we call communities that emerge on these platforms open communities. These two broad types of communities differ in important aspects and might require different engagement strategies. We tease out the strategies that allow entrepreneurs to engage and grow both types of online communities by drawing on research on the affordances of social media (Gulbrandsen et al., 2020; Heavey et al., 2020), dynamics within online communities (Glozer et al., 2019; Hampel et al., 2020), and the role of distinctiveness in stakeholder relations (Taeuscher et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2018).

Our theorizing suggests that the entrepreneurs’ content contributions to both open and core communities increase engagement in the respective communities up to a certain saturation point. However, while open communities are best served by a steady stream of relatively homogenous content, core communities are best engaged with varied content. We further theorize that open communities are significant for community growth, while core communities play no role in community growth. We test our theorizing drawing on a longitudinal case study, combining time-series regression analysis and topic modeling, in the video game industry. Our dataset includes approximately 20,000 pieces of entrepreneur-provided content and 6.5 mil. community member contributions posted on Facebook and Twitter, hosting the entrepreneur’s open community, and in an online forum, hosting the core community. In this dataset, we find evidence in support of our hypotheses.

Our study develops new insights into the diversity of online communities (e.g., Murray et al., 2020; Schou et al., 2022) and thus contributes to the emerging understanding of online community management and governance in entrepreneurial ventures (Fisher, 2019; Hampel et al., 2020; Heavey et al., 2020; Lin & Maruping, 2022; Reischauer & Mair, 2018). It also adds novel theory on community engagement and community growth. We also derive important recommendations for entrepreneurs who want to engage and grow their online communities and suggest a research agenda to deepen our understanding of online community management in entrepreneurial ventures. Our study thus also advances research on entrepreneurial communities more broadly (e.g., Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017) by adding knowledge about the roles that different online communities can play in early-stage entrepreneurship.

2 Theoretical background

2.1 The importance of (online) communities in early-stage entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurs benefit from strong social networks (Hayter, 2013; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Research has shown that entrepreneurs with access to social networks better recognize opportunities (e.g., Ma et al., 2011; Ozgen & Baron, 2007), attract more funding (e.g., Alexy et al., 2012; Jonsson & Lindbergh, 2013), and achieve higher levels of innovation and growth (e.g., Uzzi, 1996). Social networks can also give entrepreneurs access to diverse knowledge and skills that can enhance their problem-solving abilities and increase their adaptability to changing market conditions (van Burg et al., 2022). Furthermore, social networks can serve as a source of emotional support, advice, and mentorship, which can help entrepreneurs overcome the challenges and setbacks associated with starting and growing a business (Baker & Nelson, 2005). How entrepreneurs interact with their social networks will hereby differ depending on whether they are interacting with peers, competitors, or potential customers and partners (Vaast, 2023; Vissa, 2011, 2012).

Online communities represent one important form of social network (Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017; Lall et al., 2022). Online communities can take different forms. For instance, they may be meeting places where entrepreneurs help each other resolve and reframe problems, reflect on situations, and refocus their thinking and efforts (Meurer et al., 2022). Online communities can also allow access to financial resources by crowdfunding (e.g., Allison et al., 2017; Belleflamme et al., 2014; Block et al., 2018, 2021) and serve to estimate market potential (Chemla & Tinn, 2020); they can be a test bed for ideas (Schou et al., 2022), and they can provide a loyal customer base (Goh et al., 2013). Online communities can thus be an important part of many business models (Hornuf et al., 2021; Tschang, 2021).

Entrepreneurs can even build and maintain their own online communities to obtain a direct connection with potential investors, customers, or product enthusiasts. Such online communities are, as recent research has discussed, a potential advantage in the marketplace (Fisher, 2019; Gibson et al., 2021) when the entrepreneur manages to engage community members and, ideally, foster continuous community growth (Reischauer & Mair, 2018). The more active contributors a community attracts, the more motivated its members will be, which will more likely lead to a competitive advantage for the entrepreneur (Loh & Kretschmer, 2023). Therefore, an emerging stream of research discusses how entrepreneurs can foster community engagement and grow the online communities they host. For instance, entrepreneurs can provide recognition or feedback, apply gamification elements and a streamlined design, set boundaries, and exert social control (Hsieh & Vergne, 2023; Jeppesen & Frederiksen, 2006; Liao et al., 2017; Piezunka & Dahlander, 2019; Reischauer & Mair, 2018; Wu & Sukoco, 2010). Community members also expect some form of reciprocal relationship for being an active part of the community (Fisher, 2019; Gibson et al., 2021). For instance, community members expect to receive new information (Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Jeppesen & Frederiksen, 2006) or interesting insights into the entrepreneurial venture (Steigenberger, 2017). Contributing content is thus important for entrepreneurs to engage and grow the online communities they host.

2.2 Open and core communities

Entrepreneurs often maintain online communities across multiple platforms that differ substantially in the type of audience they attract (cf., Culnan & McHugh, 2010; Hanna et al., 2011). Two archetypical platforms are public-open and private-closed platforms (cf., Dobusch et al., 2019; Heavey et al., 2020).

Public-open platforms include social media platforms such as Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, and Twitter. These platforms allow simple and incidental interactions with a potentially broad audience. We call the community that forms on such platforms an open community (see Dobusch et al., 2019) and expect it to be fluid and less based on strong bonds between the entrepreneur and community members (cf., Ren et al., 2007). This is because public-open platforms typically require only a platform-wide signup, which then affords members easy access to private and venture-hosted profile pages. Barriers to entry and exit are very low. Members on such communication platforms are just one click away from participating in an online community, have a simple way to interact with the content provided, and might see this content in their social media stream; additionally, they can just as easily leave the community (Argyris & Monu, 2015; Kane et al., 2014).

Private-closed platforms are, for example, entrepreneur-hosted online fora or closed user groups (e.g., Autio et al., 2013; Jeppesen & Frederiksen, 2006; Jeppesen & Laursen, 2009). These platforms exist outside of general-interest social media and require separate sign-ups, sometimes including additional entry barriers (Dobusch et al., 2019). Becoming part of a private-closed platform is, therefore, a comparatively effortful endeavor (Dobusch et al., 2019; Kane et al., 2014). Those who commit these efforts typically identify strongly with the venture, the related product or service, or both (Ren et al., 2007). We call the community that forms on private-closed platforms the core community, consisting of self-identified individuals committed to the community's values and identity and the related entrepreneurial venture. Although it is technically not difficult to leave the core community, psychological barriers, via identification and shared values, often make community members committed to such a community. For example, Dobusch et al. (2019) explain this relation in the context of Wikipedia, where community members in the core community guard and shield the community’s borders. Other well-researched examples are the community that formed around the music production software Propellerhead (Autio et al., 2013; Dahlander & Frederiksen, 2012; Jeppesen & Frederiksen, 2006) or—albeit outside of the entrepreneurship field—the adult fan community of LEGO (Hienerth et al., 2014; Jensen et al., 2014).

In the following, we hypothesize that open and core communities display different patterns in community engagement and growth.

3 Hypothesis development

3.1 Entrepreneur-provided content, community engagement, and the role of content distinctiveness

Entrepreneurs can engage community members by providing content. Entrepreneur-provided content not only adds cognitive input (cf., Kane & Ransbotham, 2016)—for example, information on a new product that community members can discuss—but also indicates that the entrepreneur cares about the community, puts effort into communicating with community members, and contributes to a shared identity (Fisher, 2019; Goh et al., 2013; Hampel et al., 2020). Previous research thus indicates that every form of content is better than no content and that, overall, community members should appreciate additional content an entrepreneur might provide.

However, more content may sometimes also lead to less community engagement. First, more content can lead to information overload. Stakeholders have limited attention spans and are likely to miss communication if the cognitive load is too high (Maier et al., 2015; Plummer et al., 2016; Steigenberger & Wilhelm, 2018). This likely implies that the engaging effect of entrepreneur-provided content will wear off as community members become saturated and eventually oversaturated when entrepreneurs provide substantial amounts of content in a given period.

Second, the quality of content might decline with content quantity, especially in resource-constrained new ventures. Stimulating content needs to be enticing and informative while avoiding repetition (e.g., Bapna et al., 2019; Marbach et al., 2019; Steigenberger & Wilhelm, 2018; Weiger et al., 2017). Producing large quantities of such high-quality content for online communities requires dedicated resources in the form of time and creativity (cf., Kraus et al., 2019). When these resources are lacking, there is a risk that content will instead become tedious and repetitive. For instance, entrepreneurs might reuse content periodically, boring instead of exciting the audience. For online community members, the information value of such content decreases, and extra content of that kind might reduce their engagement instead of increasing it.

Combined, these effects imply that while content is important, there is a saturation point after which more content decreases, instead of increases, community engagement in both open and core communities. This reasoning leads to the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 1: The relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement follows an inverse U-shaped pattern.

Researchers have begun to study which content entrepreneurs can use to engage a community. Bapna et al. (2019), for example, found that content that focuses on firm milestones or firm offers can encourage early community engagement in brand communities. Hampel et al. (2020) discuss different communication patterns entrepreneurs can use to maintain community identification during pivots, and Piezunka and Dahlander (2019) discuss how individual feedback to crowd-sourced ideas can increase community members’ willingness to submit new ideas. This research has produced short-range theories that indicate that the engagement effect of entrepreneur-provided content is largely idiosyncratic, depending on the specific community, its specific circumstances, and the specific goals entrepreneurs have or problems they need to solve in and with their communities. To develop a more broadly applicable theory of entrepreneurial community engagement, we can follow scholars such as Reischauer and Mair (2018), who discuss community governance practices, or Goh et al. (2013), who compare directed with undirected content and classify entrepreneurs’ contributions more broadly.

An important question entrepreneurs face is the degree of content distinctiveness, which describes whether they should provide content similar to or different from what the community is used to. Distinctive content may provide more relevant intellectual stimuli (cf., Kane & Ransbotham, 2016) and thus can evoke attention and engagement (Taeuscher et al., 2021; Zhao et al., 2018). However, the desire for distinctiveness is counterweighted by a desire for conformity (Navis & Glynn, 2011). Online communities are built around shared values and interests (see Alvarez & Sachs, 2023; Hampel et al., 2020) and might thus benefit more from familiar content than from content outside expectations. It is thus not clear whether entrepreneurs are well advised to provide homogeneous content or diversify their content. This question is relevant because producing homogeneous content is typically much cheaper (cf., Garz & Rickardsson, 2022).

Considering the differences between open and core communities, we propose that it depends on the type of online community if it is worth for entrepreneurs to invest in distinctive content. Specifically, we argue that members of the core community will expect both familiar content, strengthening the shared identity with the entrepreneurial venture (Alvarez & Sachs, 2023; Hampel et al., 2020), and interesting and stimulating novel input (Baker & Bulkley, 2014; Jeppesen & Frederiksen, 2006; Kane & Ransbotham, 2016). Picking up our arguments from above, we expect that core community members will become bored faster by repetitive content and satiated slower by diverse content than open community members. Their stronger identification with the community suggests that the community is important to them relative to their other interests, and they will thus be prepared to commit more cognitive resources to the provided content. Additionally, the content in core communities does not compete for attention with other content as it does in open communities where the member’s private feed is flooded with content from other profiles. Therefore, interactions in core communities are less fleeting than those in open communities (cf., Vaast, 2023). In core communities, distinct content should therefore increase community engagement.

In open communities, where entry and exit barriers are low and membership and commitment are fluent (Argyris & Monu, 2015; Kane et al., 2014; Ren et al., 2007), the main role of entrepreneur-provided content will be to consistently (re)create community boundaries and (re)enlist community members (see Alvarez & Sachs, 2023). In open communities, the problem of information overload is exacerbated since the entrepreneur’s content competes with other content in the community member’s private feed. It is easy even for those subscribed to a community to miss content, as content could get lost in the social media news feed of each community member. Open communities are thus particularly “noisy” environments, where individual pieces of communication tend to get lost (Connelly et al., 2011; Plummer et al., 2016; Steigenberger & Wilhelm, 2018). In such environments, individual community members might not even recognize distinct content as such. We propose that content distinctiveness will therefore not matter for the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement in open communities. This leads us to the following hypothesis:

-

Hypothesis 2: Content distinctiveness positively moderates the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement in core communities but not in open communities.

3.2 Entrepreneur-provided content and community growth

Can entrepreneur-provided content also contribute to growing an online community? We again propose that this depends on the community in focus. In general, entrepreneur-provided content can lead to community growth when community members share entrepreneur-provided content with those outside the community, prompting them to join (Fisher, 2019).

This is much more likely to happen in open than in core communities. In open communities, community members can use the sharing functions native to public-open platforms to share the entrepreneur’s content so that the content is pushed into nonmembers’ social media feeds (Bapna et al., 2019). Networks such as Facebook and TikTok, for example, provide a share function, whereas Twitter allows for retweets. Entrepreneur-provided content directed at the open community might thus reach those who are potentially interested in the entrepreneurial venture but are currently not part of its communities and guide them toward either the open or the core community. Again, we would expect that the strength of this effect declines with the amount of content provided, such that after a tipping point, more content provided to the open community will no longer lead to more community growth, as community members will start to miss content and will be overloaded and thus disengage if an entrepreneur provides too much content.

Platforms on which core communities are typically hosted often do not afford such sharing or pose higher barriers, lowering the likelihood that content from the core community reaches an audience outside the core community. In addition to the lack of technical facilitation, core communities sometimes guard their boundaries and deter rather than invite newcomers (Dobusch et al., 2019), implying that core community members will be less inclined to share content an entrepreneur provides. In general, high identification can lead groups to isolate themselves from outsiders (Caprar et al., 2022), deterring content sharing. In sum, it seems unlikely that the content entrepreneurs provide to their core community will reach those outside the core community to a degree that could lead to recognizable community growth in either the core or the open community. We thus derive our final set of hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 3a: The relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content in the open community and community growth in both the open and the core community follows an inverse U-shaped pattern.

-

Hypothesis 3b: More entrepreneur-provided content in core communities is not associated with community growth in either the open or the core community.

4 Methods

4.1 Sample and data sources

We use a longitudinal study design to investigate the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content, community member engagement, and community growth over a time span of six and a half years. Our objects of investigation are the online communities related to Star Citizen, a video game built by the Los Angeles-based entrepreneurial venture Cloud Imperium Games (CIG). CIG used the online community as a funding source, as a testbed for ideas and feedback, and to reach customers. CIG is thus an appropriate empirical case for our theoretical interest in entrepreneurs who try to obtain a competitive advantage with the help of their online communities. Our period of investigation covers the time from November 20, 2012, to June 30, 2019. We chose the start date because Star Citizen had established an online community on the relevant platforms at that point. The date also matches the end of the venture's Kickstarter campaign that initiated the fundraising. We collected the data for our study between July and September 2019, which is why the sample period ends in June that year.

The company maintained an open community hosted on Facebook and Twitter and a core community hosted as an online forum on its own website. In line with our theoretical interest, access to the company’s Facebook and Twitter communities did not require additional sign-ups or passing any entry barriers, while access to the core community on the firm’s website required the user to create a specific account. We obtained all entrepreneur-provided content to the Star Citizen online community during this time frame, including on Facebook and Twitter (as the open community) as well as on the online forum (as the core community).Footnote 1

As we are interested in the effects of entrepreneur-provided content on online community participants, we prefer a single case study over a broader sample because this allows us to hold other factors constant, such as digital nudges embedded in the respective software or the community moderation approach (Reischauer & Mair, 2018). The second reason to focus on a single case is to keep our data computationally feasible while providing sufficiently homogenous data for the topic modeling, which we use to establish content distinctiveness.

We used Facebook’s Application Programming Interface (API) to download information about all 2,606 posts published by CIG on their Facebook page (https://www.facebook.com/RobertsSpaceIndustries/), including the corresponding community member comments (140,534 in total). Twitter data were obtained from Vicinitas, a commercial provider of social media data. Specifically, we purchased data on all 5,268 tweets by CIG’s official Twitter account (https://twitter.com/RobertsSpaceInd), as well as the corresponding replies by other Twitter users (43,997 in total). Data on the communication of the community in CIG’s official forum were collected using a custom-made extraction tool built in PHP. The forum started with the domain https://forums.robertsspaceindustries.com/ and migrated in 2017 to https://robertsspaceindustries.com/spectrum/community/SC. We collected all community member postings from these domains but restricted the analysis to threads moderated by staff members of CIG (6,298,166 postings in total) to keep the analysis computationally feasible and because threads without moderation are not subject to any community management. We also obtained all 11,934 postings from forum accounts marked as “staff.”

4.2 Measures

4.2.1 Community engagement

To capture community engagement, we calculated the length of social media user postings as the daily sum of characters of “comments” left by Facebook users to posts by CIG and “replies” left by Twitter users to tweets by the company (we discuss an alternative outcome measure in the robustness test section).Footnote 2 Similarly, we computed the length of forum user postings as the daily sum of characters over all postings from forum accounts not marked as “staff.” We divided both variables by 1,000 to ease the interpretation of the results. See Figs. 6, 7, 8, and 9 for graphical representations of our variables. The summary statistics in Table 1 suggest that the aggregated user postings in the forum (896,051 characters) were on average substantially longer than those on social media (7,086 characters). This is in line with our theorizing that core community members are more committed. We refrained from measuring community engagement in terms of likes or shares because these forms of “low level” user engagement require much less effort from the user than writing a comment, and they offer less nuanced information to the entrepreneur (Garz et al., 2020). Additionally, by design, those metrics do not exist in CIG’s forum.

4.2.2 Community growth

For each day, we counted the number of usernames of those who had not posted anything in the forum prior to that day as a proxy of the growth of the core community, using the label number of new forum users. We used the same approach to count new users on Twitter. This approach was not feasible on Facebook because our data did not include any usernames due to the platform’s terms and conditions. Instead, we relied on the daily number of new Page Likes of Star Citizen’s Facebook Page to capture the community’s growth. The daily number of new social media users is then defined as the number of first-time contributors on Twitter plus new Page Likes on Facebook. This measure is only available between April 14, 2016, and June 30, 2019, due to the lack of information about Facebook page likes before that time.Footnote 3 As Table 1 shows, average community growth has been similar in size on social media (mean value = 50.36) and in the forum (mean value = 55.65).

4.2.3 Amount of entrepreneur-provided content

As our main independent variables, we computed the amount of entrepreneur-provided social media content as the daily sum of characters (in 1,000) of Facebook postings and tweets by CIG’s official Facebook page and Twitter account, respectively, and the amount of entrepreneur-provided forum content as the daily sum of characters (in 1,000) of contributions from forum accounts marked as “staff” for each day. On average, we observed approx. 450 characters of entrepreneur-provided content on social media and 2,250 characters in the forum (Table 1).

4.2.4 Distinctiveness of entrepreneur-provided content

We employed topic modeling (Hannigan et al., 2019) on all entrepreneur-provided content on social media and in the forum—a corpus consisting of 1,185,376 words—to create a measure of content distinctiveness. Topic modeling has been used with increasing frequency in management and entrepreneurship research in recent years (Corritore et al., 2020; Taeuscher et al., 2021). It is a computer-aided natural language processing technique that, based on machine learning, uses statistical associations of words in large corpora of text to generate latent topics, “clusters of co-occurring words that jointly represent higher-order concepts” (Hannigan et al., 2019, p. 589; Leavitt et al., 2021). The goal of topic modeling is to use the higher-order concepts represented in the topics to “render theoretical artifacts” that can then be used in statistical analyses (Hannigan et al., 2019, p. 594).

The following analytical procedure was used to determine the topics addressed in CIG’s social media and forum content. First, we transformed the relevant text to lower case and removed punctuation, numbers, HTML, stop words, and words appearing in less than 1% or more than 20% of postings and stemmed the remaining words to their roots, following best practices in automated text analysis (Jurafsky & Martin, 2008). We then used structural topic modeling (Roberts et al., 2019), which builds on latent Dirichlet allocation (Blei et al., 2003) but allows topical covariates to be incorporated when estimating the model. Incorporating these covariates has the advantage of being able to explain differences in topical prevalence across texts based on structural factors. In our case, we used the platform and the date of the text as covariates because entrepreneur-provided content is likely tailored to the different platforms (Facebook, Twitter, forum) and talking points on a given day. We modeled the texts on Facebook, Twitter, and the forum jointly to ensure that all content was evaluated according to the same topic classification using the stm package in R (Roberts et al., 2019). We determined the number of topics k by fitting candidate models in a range from 10 to 100 topics and comparing their performance according to semantic coherence, exclusivity, and held-out likelihood. These metrics indicated that a model with k = 40 topics fits the data best, which is why we proceeded with that number of topics. Fig. 5 lists the terms with the highest probability of belonging to the different topics in the fitted model.

With this approach, we obtained the proportion of each topic on social media and in the forum on any given day in our sample. We then applied the formula used by Haans (2019) and Taeuscher et al. (2021) and calculated distinctiveness separately for social media and the forum as \({\sum }_{T=1}^{40}\mathrm{ABS}\left[\left({\theta }_{T,d}-{\overline{\theta }}_{T,D}\right)\right]\), where \({\theta }_{T,d}\) denotes the proportion for topic \(T\) on day \(d\) and \({\overline{\theta }}_{T,D}\) indicates the topic’s average proportion during a time window \(D\). We defined \(D\) as the rolling average within 7 days before and 7 days after day \(d\). Hence, for every day, distinctiveness is the sum of absolute deviations between the topics’ current proportion and their ± 7-day rolling average. Robustness checks confirm that we obtain very similar results when we use alternative lengths of the time window, such as ± 3 days, ± 14 days, and ± 30 days (results are available on request). The distinctiveness score varies between 0 and 1. A value of 0 indicates days where the topic proportions are perfectly aligned with their average proportions, whereas a value of 1 indicates the maximum possible degree of distinctiveness. As Table 1 shows, the sample mean of the distinctiveness score on social media is 0.30, and in the forum, it is 0.36.

4.2.5 Control variables

To distinguish between entrepreneur-provided content and product development progress, we created a binary variable release of new game version that takes the value 1 on dates where CIG delivered substantial updates or extensions of the Star Citizen game and 0 otherwise. We observe 20 releases of new game versions during our investigation period.

To control for psychological effects of round number events in the funding raised by CIG, we constructed a binary variable funding milestone. For example, we considered it a milestone when the cumulated funding surpassed the $10 M threshold. Following the literature (Foellmi et al., 2016; Garz & Martin, 2021), the variable takes the value 1 when the first or second digit of the overall funding amount switched (e.g., from $149,923,415 to $150,226,675 on May 20, 2017; or from $199,946,774 to $200,021,064 on November 17, 2018). The data for this variable are available from https://robertsspaceindustries.com/funding-goals, which we accessed through a Google spreadsheetFootnote 4 provided by the community. We count 144 round number events.

To account for external information, we created a variable sum of media reports that proxies the daily number of Star Citizen-related news articles. For that purpose, we searched relevant sources for articles including the term “star citizen” and counted those reports that provide original information about the project while discarding reports that merely cited information or content originally provided by CIG. Our set of relevant sources included the gaming magazines Kotaku, MMORPG, PCGamer, Polygon, and Rockpapershotgun, as well as the general interest publications Forbes, New York Times, Washington Post, and Wired.

Finally, we created a binary variable forum switching period, which takes the value 1 between November 1 and December 31, 2017, the period when the community migrated from the CIG’s old forum to the new forum.

4.3 Analytical approach

We used time series regression (Hamilton, 1994) to investigate our hypotheses. We obtained the day-to-day difference—or, technically, the first difference—of all variables before estimating the regressions. Most of our variables tend to be nonstationary (i.e., their means and/or variances change over time). Taking the first difference makes these variables stationary, a requirement to avoid spurious regression results (Phillips, 1986). Moreover, in their original form, our dependent variables are counts, which would require Poisson or negative binomial regressions to obtain consistent estimates. These kinds of regression approaches are considered less transparent than ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions and difficult to implement in a time series context (Cameron & Trivedi, 2005). Taking the first difference transforms count variables into as-good-as normally distributed variables, for which consistent OLS estimates can be obtained. First differencing also helps to purge time series from autocorrelation, which is equally necessary to obtain unbiased and efficient estimates (Hamilton, 1994).

Correlograms and portmanteau statistics (Ljung & Box, 1978, available on request) indicate minor autocorrelation in the dependent variables after taking the first difference. To avoid biased estimates, we therefore included 7 lags of the left-hand-side variable in all regressions. We also took the first differences of the control variables described above (new game version, funding milestone, sum of media reports, and forum switch) and included first differences of dummy variable sets that capture the month of the year and the day of the month, which helps us to account for seasonal and other time effects that might confound the relationships under investigation.

5 Results

The regression results pertaining to Hypothesis 1 are summarized in Table 2. In Column (1) of the table, we regress the number of characters over all social media user postings on a specific day (i.e., our measure of community engagement) on the amount and squared amount of all entrepreneur-provided content on social media on that day. The coefficient on the amount of content is positive, whereas the sign is negative for the squared amount. Both coefficients are statistically significant at the 1% level. Hence, an increase in entrepreneur-provided content on social media leads to more community engagement until a tipping point is reached, after which further increases in entrepreneur-provided content are associated with decreases in community engagement. Using the formula \(\frac{-\mathrm{amount}}{(2 \times \mathrm{ squared amount})}\), we calculate the tipping point to be \(\frac{-4.855}{(2 \times -0.453)}\) = 5,359 or 5,359 characters. On average, CIG posted content on Facebook or Twitter in the amount of 450 characters per day, which is distinctly below the tipping point and implies that the company did not fully utilize its possibilities to promote community engagement (cp. Fig. 1). We observe only two days during the sample period where the amount of entrepreneur-provided content exceeded the tipping point (5,713 characters on Aug 10, 2016, and 7,917 characters on Jun 20, 2017)—these are days where extra content decreased, instead of increased, community engagement.

The results on the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement in the forum are shown in Table 2, Column (3). Accordingly, the signs of the relevant coefficients (positive for the amount and negative for the squared amount) again indicate an inverse U-shaped relationship. These coefficients are significant at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. Using the same formula as above, we calculate a tipping point of \(\frac{-8.340}{(2 \times -0.271)}\) = 15.387 or 15,387 characters. Figure 2 offers a graphical representation of the relationship. We again note that CIG underutilized the engagement-creating potential of its content, considering that the sample mean of entrepreneur-provided content in the forum (2,250 characters) was clearly below the tipping point. We observe 31 occasions where the company provided more content than optimal.

We support Hypothesis 1, which states that the relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement follows an inverse U-shaped pattern. It is also interesting to note that the tipping point in the forum is almost three times higher than on Facebook and Twitter, indicating that the core community expects and appreciates much more entrepreneur-created content than the open community.

To test whether content distinctiveness moderates the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content and community engagement in core but not open communities (Hypothesis 2), we interact the amount of content with the distinctiveness score.Footnote 5 The results for the open community (i.e., social media) are shown in Column (2) of Table 2, according to which there is no statistically significant interaction effect between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and its distinctiveness. For engagement on Facebook or Twitter, it does not matter whether the provided content is different from other content provided in a seven-day time window. Robustness tests indicate, as discussed above, that this finding is not contingent on the length of the time window. As shown in Fig. 3, the regression lines are virtually parallel when comparing hypothetical scenarios of zero and maximum distinctiveness, which confirms the absence of any moderation effects.

In contrast, we find a statistically significant interaction effect between these variables (at the 1% level) when looking at the estimates pertaining to the forum in Column (4) of Table 2. As hypothesized, this interaction is positive. Figure 4 illustrates that the higher the returns to posting more content in the forum were, the more distinct this content was from the average topic distribution. That is, the slope of the regression line is much steeper on days with a high distinctiveness score. Thus, we support Hypothesis 2.

In Table 3, we evaluate how entrepreneur-provided content relates to community growth (Hypotheses 3a and 3b).Footnote 6 As Column (1) of the table shows, an increase in the amount of entrepreneur-provided content on social media is associated with an increase in the number of new users in the open community. The relevant coefficient (12.484) is positive and significant at the 1% level. The coefficient on the squared amount of this content is negative and significant at the 5% level, which indicates that the relationship between both variables follows an inverse U-shape—from a certain point on, more content no longer leads to more growth. In contrast, we do not find a statistically significant relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content in the forum and the number of new social media users. The same applies when we relate the amount of forum content to community growth in the forum—the relevant coefficients in Column (3) of Table 3 are not significant. However, we find a positive, borderline significant coefficient when looking at the relation between the amount of entrepreneur-provided social media content and the number of new forum users (at the 10% level), yet the related squared values are not statistically significant. Hence, we find partial support for Hypothesis 3a and full support for Hypothesis 3b. Our results further indicate that content distinctiveness does not moderate the relationship between entrepreneur-provided content and community growth.

6 Robustness tests

To test the robustness of our results, we calculated our models above with an alternative measure for community engagement based on sentiment analysis. The rationale for using a sentiment-based measure of community engagement is that community engagement, understood as the amount and length of user postings, may not always benefit the entrepreneur but that the quality of the interactions matters. Sentiment analysis has been previously used to analyze Twitter data (Kouloumpis et al., 2011; Sarlan et al., 2014) and entrepreneur-mentor interactions in online communities (e.g., Mason et al., 2021). We pursued a dictionary-based approach (Pang & Lee, 2008), capturing the subjectivity and polarity of community postings, as outlined in the online appendix.

The subjectivity of community postings is defined as the sum of negative and positive words divided by the number of all words on a given day in the community. This variable ranges from 0 to 0.82 on social media (mean = 0.51) and from 0 to 0.72 in the forum (mean = 0.60). Higher values imply that users engage more emotionally or more “warmly”, whereas low values reflect more objective or “colder” contributions. The polarity of community postings refers to the number of positive words minus the number of negative words divided by the sum of negative and positive words. This measure ranges from -0.50 to 0.92 on social media (mean = 0.32) and from -0.16 to 0.68 in the forum (mean = 0.23). Here, values larger than zero indicate that community postings include more positive than negative words, whereas the opposite applies when the polarity measure is below zero.

The results pertaining to the subjectivity of community postings are presented in Table 4. According to Column (1) of the table, the relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content on social media and the subjectivity of social media community postings also follows an inverse U-shape. That is, initially, more entrepreneur-provided content increases the use of emotionally connotated words, but once a tipping point is reached, further increases in entrepreneur-provided content are associated with decreases in the “warmth” of users’ social media posts. We do not find a significant relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and the subjectivity of community postings in the forum (Column 3). In addition, the results indicate a borderline significant moderation effect of the distinctiveness of entrepreneur-provided content on this relationship in the forum (Column 4) but not on social media (Column 2).

The results on the role of entrepreneur-provided content in the polarity of community postings are summarized in Table 5. We find an inverse U-shaped relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and the polarity of social media user postings (Column 1), implying that increasing this content improves sentiment until a tipping point is reached. After that, further increases in entrepreneur-provided content are associated with more negative social media user postings. We do not find a significant relationship between the amount of entrepreneur-provided content and the polarity of community postings in the forum (Column 3), nor are there any indications of significant moderation effects of the distinctiveness measure (Columns 2 and 4). In conclusion, entrepreneur-provided content plays an important role in community sentiment, especially in open communities. These tests strengthen the robustness of our main analysis.

7 Discussion

Social networks are central to entrepreneurship since they can provide entrepreneurs with support and resources (Cornelius & Gokpinar, 2020; Hayter, 2013; Lin & Maruping, 2022; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Accordingly, the question of how entrepreneurs can build and engage their social networks is a cornerstone of entrepreneurship research (Hayter, 2013; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Within this research field, scholars began to focus on online communities as relatively cost-effective ways for entrepreneurs to interact with small-scale investors, peers, customers, or product enthusiasts to obtain resources, support, ideas, or gain market access (e.g., Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017; Lall et al., 2022; Meurer et al., 2022). This research found that online communities can be an important source of competitive advantage for entrepreneurial ventures, and scholars have begun to develop insights into the management of online communities (Fisher, 2019; Hampel et al., 2020; Heavey et al., 2020; Reischauer & Mair, 2018).

Our research shows how different communication platforms contribute to the diversity of online communities and how entrepreneurs can leverage this diversity. Previous research has pointed out the diversity of community members within single communication platforms, for instance, concerning motivations to participate in and crowdfund an entrepreneurial project on Kickstarter (Murray et al., 2020), contributions of user innovations in a firm-hosted online forum (Dahlander & Frederiksen, 2012), or different forms of support on Reddit (Schou et al., 2022). Our study demonstrates the relevance and usefulness of distinguishing between at least two types of communities, open and core communities, that emerge from open (e.g., social media) and closed (e.g., online fora) platforms, respectively. Mechanisms and relationships that are in place in one community might not replicate in another community.

Considering the diversity and complementarity of communication platforms contributes to ongoing discussions about online community management and governance (He et al., 2020; Hsieh & Vergne, 2023; Loh & Kretschmer, 2023; Reischauer & Mair, 2018). Specifically, our insights allow us to complement previous, more idiosyncratic advice on how entrepreneurs can engage and grow their online communities (e.g., Bapna et al., 2019; Hampel et al., 2020; Piezunka & Dahlander, 2019).

First, our paper expands prior research on the relevance of providing content to online communities (Bapna et al., 2019; Marbach et al., 2019; Steigenberger, 2017; Weiger et al., 2017). Our findings outline that providing more content is not always good for either engagement or growth. Instead, our theorization and findings indicate a saturation point after which entrepreneurs endanger their prospects by adding more content. In addition to theorizing the content amount, we introduce a measure of content distinctiveness—grounded in topic modeling—to the literature, suggesting that it does not only matter how well the content is written and designed (Bapna et al., 2019; Marbach et al., 2019; Weiger et al., 2017) but also how much the content differs over time. Here, we again find evidence for the usefulness of distinguishing between community types. We theorize and find that content distinctiveness matters more in core communities, where a relatively smaller group of more dedicated community members are particularly likely to provide resources to a venture—such as ideas, feedback, and financial contributions.

Second, we observe an asymmetrical spillover effect where the growth of open communities also increases the size of core communities, but not vice versa. This questions the sequential logic previously reported in other research where communities grow from smaller, core communities into larger ones (e.g., Murray et al., 2020). While this might be the case during an initial gestation period, our longitudinal data suggest the role of core communities in growth changes afterward. Open and core communities are thus complementary. On the one hand, open—often larger—communities drive growth across communities but do not contribute ideas, feedback, and financial contributions to the same extent. On the other hand, closed—often smaller—communities provide useful input, but it is difficult for them to grow by themselves. Instead, they benefit from the growth that the open communities instigate. These findings deepen our understanding of community growth and engagement in online communities.

Our study further provides evidence for the wider literature on social networks and communities in entrepreneurship (Cornelius & Gokpinar, 2020; Hayter, 2013; Lin & Maruping, 2022; Slotte-Kock & Coviello, 2010). Research on entrepreneurship and social networks has developed deep insights into how entrepreneurs use other forms of engagement, for example, in crowdfunding (e.g., Belleflamme et al., 2014; Block et al., 2018, 2021; Chemla & Tinn, 2020) and peer communities (e.g., Lall et al., 2022; Meurer et al., 2022; Schou et al., 2022) or when they communicate with mentors (Kuhn & Galloway, 2015; Kuhn et al., 2017) and potential new business partners (Vissa, 2011, 2012). However, thus far, our understanding of what entrepreneurs need to do to leverage communities they host on their own platforms was (and still is) limited. We spell out one type of interaction entrepreneurs can use—providing content to others in the social network—to exert control over the degree to which they have communities available and can obtain a community advantage. Developing this line of research is important because online communities are very accessible to entrepreneurs, particularly if their business model centers on a product or service suited to attract attention and commitment (Hampel et al., 2020), and can thus be an important part of an entrepreneur’s social network.

7.1 Practical contributions

Distinguishing open from core online communities is important for entrepreneurial practice. Entrepreneurs grow and engage their online communities via the content they provide for those communities, and it is therefore important to understand how much and which content to provide. More content is often but not always better, and entrepreneurs need to pay attention to where the tipping point lies and how it depends on which type of community they interact with. Core communities seem to respond better to less but more distinctive content. Open communities, which drive overall community growth, require more but rather homogeneous content. Considering these insights allows entrepreneurs to use their resources better since content production can be costly, especially for resource-constrained new ventures (cf., Kraus et al., 2019).

7.2 Limitations and future research directions

Our study has limitations, which provide opportunities for future research. First, it is based on a single case, and additional tests of our hypotheses are therefore necessary. For example, future research might study whether the same mechanisms also apply in online communities of different sizes. Second, based on our method, we cannot interpret our results in a causal way. Specifically, we cannot rule out reverse causality, that user engagement triggered entrepreneur-provided content. Such a direction seems unlikely as a general pattern but might have occurred in specific situations, for example, when discussions got out of hand and the entrepreneur provided content in response. An interesting methodological question in that regard is how long it takes for entrepreneur-provided content to affect community behavior. In our paper, we see associations in the same observation period (the same day), which is plausible, as the entrepreneur, in our case, provided so much content that the content from day t would be quickly superseded by content from day t + 1. The nature of our dependent variables (responding to content) also implies that community members typically respond immediately or not at all. Other community-related outcomes, for example, financial contributions obtained from the community, or other content patterns, for example, entrepreneurs providing new content more rarely, might imply that the effect of entrepreneur-provided content occurs with a time lag or over several days. Future research might illuminate these temporal patterns.

An important further direction for future research would be to flesh out our distinction between core and open communities. To move away from microlevel and idiosyncratic theorizing, future research could expand on the binary distinction, studying, for example, to what degree and under which circumstances different community types matter comparatively more or less for different community outcomes, such as ideas (e.g., Piezunka & Dahlander, 2019) or financial contributions (e.g., Block et al., 2018, 2021). While our separation of open and core communities seems to be an analytically and empirically useful starting point, it is obviously coarse. Empirically, there are communities that do not fall cleanly into those two categories, such as Reddit groups, which are technically public-open platforms but host very specific audiences more akin to our definition of a core community (Meurer et al., 2022; Schou et al., 2022). Closed or hidden Facebook groups or groups on platforms such as GitHub (He et al., 2020; Lin & Maruping, 2022) might be a comparable phenomenon that does not fall clearly into one of the two camps.

Finally, future research might consider the effects of community and venture size and the online community’s role for a venture on the outlined relationships. In our data, we studied a comparatively small (entrepreneurial) venture with a large online community, where the community was a central part of the business model of the entrepreneurial venture. Future research could fruitfully study whether the relationships we unearth also hold when the hosting venture is large, when the online community is not central to the business model or when online communities are small.

In sum, our paper contributes a mid-range theory on entrepreneurs’ online community management, which can complement idiosyncratic advice on how to engage and grow online communities (Bapna et al., 2019; Hampel et al., 2020; Piezunka & Dahlander, 2019). Providing such mid-range theories seems important for our ability to provide broader (instead of ever-more-specific) advice and understanding in the important context of how entrepreneurs can enlist and grow an online community.

Data Availability

A data replication kit is available from the authors upon request.

Notes

We omit postings of CIG made on its information channel “RSI Comm-Link”, which is hosted on the same website as the forum (https://robertsspaceindustries.com/comm-link). These postings correlate with the provision of content on its social media channels and in the forum. Hence, the content provision on the RSI Comm-Link refers to the same construct as content provision on social media and in the forum but does not allow us to distinguish between platforms, which is why we refrain from including these postings in the analysis.

As a robustness test, we further capture community engagement with sentiment-based measures. The results for this additional analysis are presented after the main analysis.

In the case of community growth in the forum, the results reported in Table 3 pertain to the full sample (Nov 20, 2012 – Jun 30, 2019). We obtain qualitatively similar results (available on request) when we restrict the analysis of community growth in the forum to the period for which data on social media community growth were available (Apr 14, 2016 – Jun 30, 2019).

We test the hypothesis in a regression that does not include the squared amount of entrepreneur-provided content because any coefficients are difficult to interpret when the main explanatory variable is simultaneously part of two interaction effects (i.e., amount × amount and amount × distinctiveness).

To keep the results presentation symmetric and transparent, we include content distinctiveness (as in Table 2), even though we do not have hypotheses about moderation effects in the case of community growth.

References

Alexy, O. T., Block, J. H., Sandner, P., & Wal, A. L. J. T. (2012). Social capital of venture capitalists and start-up funding. Small Business Economics, 39(4), 835–851. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9337-4

Allison, T. H., Davis, B. C., Webb, J. W., & Short, J. C. (2017). Persuasion in crowdfunding: An elaboration likelihood model of crowdfunding performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 32(6), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.09.002

Alvarez, S. A., & Sachs, S. (2023). Where do stakeholders come from? Academy of Management Review, 48(2), 187–202. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2019.0077

Argyris, Y. A., & Monu, K. (2015). Corporate use of social media: Technology affordance and external stakeholder relations. Journal of Organizational Computing and Electronic Commerce, 25(2), 140–168. https://doi.org/10.1080/10919392.2015.1033940

Autio, E., Dahlander, L., & Frederiksen, L. (2013). Information exposure, opportunity evaluation, and entrepreneurial action: An investigation of an online user community. Academy of Management Journal, 56(5), 1348–1371. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.0328

Baker, W. E., & Bulkley, N. (2014). Paying it forward vs. rewarding reputation: Mechanisms of generalized reciprocity. Organization Science, 25(5), 1493–1510. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2014.0920

Baker, T., & Nelson, R. E. (2005). Creating something from nothing: Resource construction through entrepreneurial bricolage. Administrative Science Quarterly, 50(3), 329–366. https://doi.org/10.2189/asqu.2005.50.3.329

Bapna, S., Benner, M. J., & Qiu, L. (2019). Nurturing online communities: An empirical investigation. MIS Quarterly, 43(2), 425–452. https://doi.org/10.25300/misq/2019/14530

Belleflamme, P., Lambert, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2014). Crowdfunding: Tapping the right crowd. Journal of Business Venturing, 29(5), 585–609. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2013.07.003

Blei, D. M., Ng, A. Y., & Jordan, M. I. (2003). Latent dirichlet allocation. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 3, 993–1022.

Block, J. H., Colombo, M. G., Cumming, D. J., & Vismara, S. (2018). New players in entrepreneurial finance and why they are there. Small Business Economics, 50(2), 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9826-6

Block, J. H., Groh, A., Hornuf, L., Vanacker, T., & Vismara, S. (2021). The entrepreneurial finance markets of the future: A comparison of crowdfunding and initial coin offerings. Small Business Economics, 57(2), 865–882. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00330-2

Cameron, A. C., & Trivedi, P. K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and applications. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Caprar, D. V., Walker, B. W., & Ashforth, B. E. (2022). The dark side of strong identification in organizations: A conceptual review. Academy of Management Annals, 16(2), 759–805. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2020.0338

Castelló, I., Etter, M., & Nielsen, F. Å. (2016). Strategies of legitimacy through social media: The networked strategy. Journal of Management Studies, 53(3), 402–432. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12145

Chemla, G., & Tinn, K. (2020). Learning through crowdfunding. Management Science, 66(5), 1783–1801. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3278

Connelly, B. L., Certo, S. T., Ireland, R. D., & Reutzel, C. R. (2011). Signaling theory: A review and assessment. Journal of Management, 37(1), 39–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310388419

Cornelius, P. B., & Gokpinar, B. (2020). The role of customer investor involvement in crowdfunding success. Management Science, 66(1), 452–472. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3211

Corritore, M., Goldberg, A., & Srivastava, S. B. (2020). Duality in diversity: How intrapersonal and interpersonal cultural heterogeneity relate to firm performance. Administrative Science Quarterly, 65(2), 359–394. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839219844175

Culnan, M. J., & McHugh, P. J. (2010). How large US companies can use Twitter and other social media to gain business value. MIS Quarterly Executive, 9(4), 243–259.

Dahlander, L., & Frederiksen, L. (2012). The core and cosmopolitans: A relational view of innovation in user communities. Organization Science, 23(4), 988–1007. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0673

Dobusch, L., Dobusch, L., & Müller-Seitz, G. (2019). Closing for the benefit of openness? The case of Wikimedia’s open strategy process. Organization Studies, 40(3), 343–370. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617736930

Fisher, G. (2019). Online communities and firm advantages. Academy of Management Review, 44(2), 279–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2015.0290

Foellmi, R., Legge, S., & Schmid, L. (2016). Do professionals get it right? Limited attention and risk-taking behaviour. The Economic Journal, 126(592), 724–755. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12375

Garz, M., & Martin, G. J. (2021). Media influence on vote choices: Unemployment news and incumbents’ electoral prospects. American Journal of Political Science, 65(2), 278–293. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajps.12539

Garz, M., & Rickardsson, J. (2022). Ownership and media slant: Evidence from Swedish newspapers. Kyklos, 76(1), 18–40. https://doi.org/10.1111/kykl.12318

Garz, M., Sörensen, J., & Stone, D. F. (2020). Partisan selective engagement: evidence from Facebook. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 177, 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2020.06.016

Gibson, C. B., Gibson, S. C., & Webster, Q. (2021). Expanding our resources: including community in the resource-based view of the firm. Journal of Management, 47(7), 1878–1898. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320987289

Glozer, S., Caruana, R., & Hibbert, S. A. (2019). The never-ending story: Discursive legitimation in social media dialogue. Organization Studies, 40(5), 625–650. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840617751006

Goh, K. Y., Heng, C. S., & Lin, Z. (2013). Social media brand community and consumer behavior: Quantifying the relative impact of user- and marketer-generated content. Information Systems Research, 24(1), 88–107. https://doi.org/10.1287/isre.1120.0469

Gulbrandsen, I. T., Plesner, U., & Raviola, E. (2020). New media and strategy research: Towards a relational agency approach. International Journal of Management Reviews, 22(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12213

Haans, R. F. J. (2019). What’s the value of being different when everyone is? The effects of distinctiveness on performance in homogeneous versus heterogeneous categories. Strategic Management Journal, 40(1), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2978

Hamilton, J. (1994). Time series analysis. Princeton University Press.

Hampel, C. E., Tracey, P., & Weber, K. (2020). The art of the pivot: How new ventures manage identification relationships with stakeholders as they change direction. Academy of Management Journal, 63(2), 440–471. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2017.0460

Hanna, R., Rohm, A., & Crittenden, V. L. (2011). We’re all connected: The power of the social media ecosystem. Business Horizons, 54(3), 265–273. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007

Hannigan, T. R., Haans, R. F. J., Vakili, K., Tchalian, H., Glaser, V. L., Wang, M. S., Kaplan, S., & Jennings, P. D. (2019). Topic modeling in management research: Rendering new theory from textual data. Academy of Management Annals, 13(2), 586–632. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2017.0099

Hayter, C. S. (2013). Conceptualizing knowledge-based entrepreneurship networks: Perspectives from the literature. Small Business Economics, 41(4), 899–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9512-x

He, V. F., Puranam, P., Shrestha, Y. R., & Krogh, G. (2020). Resolving governance disputes in communities: A study of software license decisions. Strategic Management Journal, 41(10), 1837–1868. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3181

Heavey, C., Simsek, Z., Kyprianou, C., & Risius, M. (2020). How do strategic leaders engage with social media? A theoretical framework for research and practice. Strategic Management Journal, 41(8), 1490–1527. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3156

Hertel, C., Binder, J., & Fauchart, E. (2021). Getting more from many—A framework of community resourcefulness in new venture creation. Journal of Business Venturing, 36(3), 106094. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2021.106094

Hienerth, C., Lettl, C., & Keinz, P. (2014). Synergies among producer firms, lead users, and user communities: The case of the LEGO producer–user ecosystem. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31(4), 848–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12127

Hornuf, L., Kück, T., & Schwienbacher, A. (2021). Initial coin offerings, information disclosure, and fraud. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 1741–1759. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00471-y

Hsieh, Y. Y., & Vergne, J. P. (2023). The future of the web? The coordination and early-stage growth of decentralized platforms. Strategic Management Journal, 44(3), 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3455

Jensen, M. B., Hienerth, C., & Lettl, C. (2014). Forecasting the commercial attractiveness of user-generated designs using online data: An empirical study within the LEGO user community. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 31, 75–93. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12193

Jeppesen, L. B., & Frederiksen, L. (2006). Why do users contribute to firm-hosted user communities? The case of computer-controlled music instruments. Organization Science, 17(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0156

Jeppesen, L. B., & Laursen, K. (2009). The role of lead users in knowledge sharing. Research Policy, 38(10), 1582–1589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.09.002

Jonsson, S., & Lindbergh, J. (2013). The development of social capital and financing of entrepreneurial firms: From financial bootstrapping to bank funding. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(4), 661–686. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00485.x

Jurafsky, D., & Martin, J. H. (2008). Speech and language processing. Prentice Hall.

Kane, G. C., & Ransbotham, S. (2016). Content as community regulator: The recursive relationship between consumption and contribution in open collaboration communities. Organization Science, 27(5), 1258–1274. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2016.1075

Kane, G. C., Alavi, M., Labianca, G., & Borgatti, S. P. (2014). What’s different about social media networks? A framework and research agenda. MIS Quarterly, 38(1), 274–304. https://doi.org/10.25300/misq/2014/38.1.13

Kouloumpis, E., Wilson, T., & Moore, J. (2011). Twitter sentiment analysis: The good the bad and the OMG! Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, 5(1), 538–541. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v5i1.14185

Kraus, S., Gast, J., Schleich, M., Jones, P., & Ritter, M. (2019). Content is king: How SMEs create content for social media marketing under limited resources. Journal of Macromarketing, 39(4), 415–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/0276146719882746

Kuhn, K. M., & Galloway, T. L. (2015). With a little help from my competitors: Peer networking among artisan entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(3), 571–600. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12053

Kuhn, K. M., Galloway, T. L., & Collins-Williams, M. (2017). Simply the best: An exploration of advice that small business owners value. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 8, 33–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2017.05.003

Lall, S. A., Chen, L. W., & Mason, D. P. (2022). Digital platforms and entrepreneurial support: A field experiment in online mentoring. Small Business Economics, 61(2), 631–654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-022-00704-8

Leavitt, K., Schabram, K., Hariharan, P., & Barnes, C. M. (2021). Ghost in the machine: On organizational theory in the age of machine learning. Academy of Management Review, 46(4), 750–777. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2019.0247

Liao, J., Huang, M., & Xiao, B. (2017). Promoting continual member participation in firm-hosted online brand communities: An organizational socialization approach. Journal of Business Research, 71, 92–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.10.013

Lin, Y. K., & Maruping, L. M. (2022). Open source collaboration in digital entrepreneurship. Organization Science, 33(1), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2021.1538

Ljung, G. M., & Box, G. E. P. (1978). On a measure of lack of fit in time series models. Biometrika, 65(2), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1093/biomet/65.2.297

Loh, J., & Kretschmer, T. (2023). Online communities on competing platforms: Evidence from game wikis. Strategic Management Journal, 44(2), 441–476. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3442

Ma, R., Huang, Y. C., & Shenkar, O. (2011). Social networks and opportunity recognition: A cultural comparison between Taiwan and the United States. Strategic Management Journal, 32(11), 1183–1205. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.933

Maier, C., Laumer, S., Eckhardt, A., & Weitzel, T. (2015). Giving too much social support: Social overload on social networking sites. European Journal of Information Systems, 24(5), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2014.3

Marbach, J., Lages, C., Nunan, D., & Ekinci, Y. (2019). Consumer engagement in online brand communities: The moderating role of personal values. European Journal of Marketing, 53(9), 1671–1700. https://doi.org/10.1108/ejm-10-2017-0721

Mason, D. P., Chen, L. W., & Lall, S. A. (2021). Can institutional support improve volunteer quality? An analysis of online volunteer mentors. VOLUNTAS: International Journal of Voluntary and Nonprofit Organizations, 33(3), 641–655. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11266-021-00351-9

Meurer, M. M., Waldkirch, M., Schou, P. K., Bucher, E. L., & Burmeister-Lamp, K. (2022). Digital affordances: How entrepreneurs access support in online communities during the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 637–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00540-2

Miller, K. D., Fabian, F., & Lin, S.-J. (2009). Strategies for online communities. Strategic Management Journal, 30(3), 305–322. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.735

Murray, A., Kotha, S., & Fisher, G. (2020). Community-based resource mobilization: How entrepreneurs acquire resources from distributed non-professionals via crowdfunding. Organization Science, 31(4), 960–989. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2019.1339

Nambisan, S. (2017). Digital entrepreneurship: Toward a digital technology perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1029–1055. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12254

Navis, C., & Glynn, M. A. (2011). Legitimate distinctiveness and the entrepreneurial identity: Influence on investor judgments of new venture plausibility. Academy of Management Review, 36(3), 479–499. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.0361

Ozgen, E., & Baron, R. A. (2007). Social sources of information in opportunity recognition: Effects of mentors, industry networks, and professional forums. Journal of Business Venturing, 22(2), 174–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2005.12.001

Pang, B., & Lee, L. (2008). Opinion mining and sentiment analysis. Foundations and Trends® in Information Retrieval, 2(1–2), 1–135. https://doi.org/10.1561/1500000011

Phillips, P. C. B. (1986). Understanding spurious regressions in econometrics. Journal of Econometrics, 33(3), 311–340. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-4076(86)90001-1

Piezunka, H., & Dahlander, L. (2019). Idea rejected, tie formed: Organizations’ feedback on crowdsourced ideas. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 503–530. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.0703

Plummer, L. A., Allison, T. H., & Connelly, B. L. (2016). Better together? Signaling interactions in new venture pursuit of initial external capital. Academy of Management Journal, 59(5), 1585–1604. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2013.0100

Reischauer, G., & Mair, J. (2018). How organizations strategically govern online communities: Lessons from the sharing economy. Academy of Management Discoveries, 4(3), 220–247. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0164

Ren, Y., Kraut, R., & Kiesler, S. (2007). Applying common identity and bond theory to design of online communities. Organization Studies, 28(3), 377–408. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840607076007

Ren, Y., Harper, F. M., Drenner, S., Terveen, L., Kiesler, S., Riedl, J., & Kraut, R. E. (2012). Building member attachement in online communities: Applying theories of group identity and interpersonal bonds. MIS Quarterly, 36(3), 841–864. https://doi.org/10.2307/41703483

Roberts, M. E., Stewart, B. M., & Tingley, D. (2019). Stm: An R package for structural topic models. Journal of Statistical Software, 91(2), 1–40. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v091.i02

Sarlan, A., Nadam, C., & Basri, S. (2014). Twitter sentiment analysis. In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Information Technology and Multimedia (pp. 212–216). Putaraja, Malaysia: IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICIMU.2014.7066632.

Schou, P. K., Bucher, E., & Waldkirch, M. (2022). Entrepreneurial learning in online communities. Small Business Economics, 58(4), 2087–2108. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-021-00502-8

Seigner, B. D. C., Milanov, H., Lundmark, E., & Shepherd, D. A. (2023). Tweeting like Elon? Provocative language, new-venture status, and audience engagement on social media. Journal of Business Venturing, 38(2), 106282. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2022.106282

Slotte-Kock, S., & Coviello, N. (2010). Entrepreneurship research on network processes: A review and ways forward. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 34(1), 31–57. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2009.00311.x

Steigenberger, N. (2017). Why supporters contribute to reward-based crowdfunding. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 23(2), 336–353. https://doi.org/10.1108/ijebr-04-2016-0117

Steigenberger, N., & Wilhelm, H. (2018). Extending signaling theory to rhetorical signals: Evidence from crowdfunding. Organization Science, 29(3), 529–546. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2017.1195

Taeuscher, K., Bouncken, R., & Pesch, R. (2021). Gaining legitimacy by being different: Optimal distinctiveness in crowdfunding platforms. Academy of Management Journal, 64(1), 149–179. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.0620