Abstract

This article offers insights into the practices of a non-formal education programme for youth provided by the European Union (EU). It takes a qualitative approach and is based on a case study of the European Voluntary Service (EVS). Data were collected during individual and focus group interviews with learners (the EVS volunteers), decision takers and trainers, with the aim of deriving an understanding of learning in non-formal education. The research questions concerned learning, the recognition of learning and perspectives of usefulness. The study also examined the Youthpass documentation tool as a key to understanding the recognition of learning and to determine whether the learning was useful for learners (the volunteers). The findings and analysis offer several interpretations of learning, and the recognition of learning, which take place in non-formal education. The findings also revealed that it is complicated to divide learning into formal and non-formal categories; instead, non-formal education is useful for individual learners when both formal and non-formal educational contexts are integrated. As a consequence, the division of formal and non-formal (and possibly even informal) learning creates a gap which works against the development of flexible and interconnected education with ubiquitous learning and mobility within and across formal and non-formal education. This development is not in the best interests of learners, especially when seeking useful learning and education for youth (what the authors term “youthful” for youth in action).

Résumé

Pour la jeunesse en action, apprendre par l’éducation non formelle est-il « avanta-jeune » ? – L’article étudie les pratiques d’un programme d’éducation non formelle pour la jeunesse mené par l’Union européenne (UE). Il se fonde sur une étude de cas du service volontaire européen (SVE), pour laquelle il a adopté une démarche qualitative. La collecte des données lors d’entretiens individuels et de groupes avec des apprenants – les volontaires du SVE –, des décisionnaires et des formateurs visait à comprendre le processus d’apprentissage dans l’éducation non formelle. Les questions de recherche traitaient de l’apprentissage, de sa reconnaissance et de son utilité perçue. L’étude a également analysé le certificat Youthpass, outil essentiel pour comprendre comment l’apprentissage est reconnu et pour déterminer s’il a été utile aux apprenants (les volontaires). Ses conclusions et analyses ont mis à jour différentes interprétations de l’apprentissage et de sa reconnaissance dans une éducation non formelle. Elles ont également démontré qu’il est difficile de distinguer la part formelle et non formelle d’un apprentissage : l’éducation non formelle est en effet utile à des apprenants individuels lorsque les contextes éducatifs formel et non formel sont intégrés. En conséquence, diviser l’apprentissage entre formel et non formel (voire, éventuellement, informel) crée un fossé qui va contre l’élaboration d’une éducation flexible et interconnectée, où apprentissage et mobilité se mêlent constamment, dans et à travers l’éducation formelle et non formelle. Une telle scission n’est pas dans l’intérêt des apprenants, en particulier si l’on recherche un apprentissage et une éducation utiles aux jeunes (le présent article les qualifiera d’ « avanta-jeunes » pour la jeunesse en action).

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

Young people in Europe who want to travel to another country to gain work experience, develop foreign language skills, and take part in voluntary work to contribute to society, can participate in the European Voluntary Service (EVS). This is a non-formal education programme for youth aged between 17 and 30 who seek learning opportunities outside the established formal school system. The programme is one example of various societal developments in Europe which emphasise the relevance of a lifelong and lifewide education for learners who are increasingly mobile, and which encompass formal, non-formal and informal learning spaces and a move towards flexible lifelong learning systems (UNESCO 2015). The interest in specific forms of learning, such as formal, non-formal and informal, began with the 1960s “world educational crisis” (Coombs 1968; Rogers 2004).Footnote 1 Policies from the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) and the European Union (EU), as well as the work of researchers, have all demonstrated that interest in this field continues around the world (UNESCO 2015; EC 2014; Harring et al. 2016). In this article, we examine learning in non-formal education as a way of contributing to an understanding of lifelong, lifewide education and how it may be useful for those youth who participate.

The purpose of our study was to contribute to research about learning within a non-formal education programme. Our qualitative approach is based on a case study which offers insight into the practices of EVS, a non-formal education programme for youth in Europe. EVS was chosen as the context for the study because non-formal learning is a key concept of the programme, and because research on learning in the programme is lacking. We were particularly interested in the Youthpass, which was introduced into the programme as a “recognition tool for non-formal and informal learning in youth work” (EC 2005). We also thought that it might be interesting to develop insights into a non-formal education programme financed by the EU, because a lot of effort and large sums of money have been invested in vocational education and training (VET) and adult education for the period 2014–2020 (EC 2013) in an attempt to promote non-formal learning.

Our contribution to the understanding of learning in non-formal education is grounded in the perspective that learners now have many opportunities to connect to spaces of information, communication, learning and education with the help of information and communication technologies (ICTs) which are increasingly available in education and society as a whole (Norberg et al. 2011; Floridi 2014; Jahnke 2016), and which can also be described as ubiquitous learning Footnote 2 (Cope and Kalantzis 2009). Additionally, the use of mobility as a strategy to pursue educational goals and contribute to the expansion of cross-border academic collaboration (EHEA 2012) is now developing as a form of mobility between formal, non-formal and informal learning spaces (UNESCO 2015).

The aim of our article is addressed through three research questions (RQs) which concern learning, the recognition of learning, and perspectives of usefulness:

-

(1)

In what ways do various stakeholders describe learning in EVS? (RQ1)

-

(2)

How is learning recognised in EVS, and what role does the Youthpass play in the recognition of learning? (RQ2)

-

(3)

How is learning through EVS understood by various stakeholders in terms of usefulness, and for whom is it perceived to be useful? (RQ3)

In the following section, we contextualise our field of interest and discuss the background of various viewpoints on learning in non-formal education. This is followed by our research methodology and its theoretical underpinnings, a description of the project, and an outline of how the data are presented. Thereafter, we describe the findings, followed by an analysis and discussion which addresses and answers the research questions. Finally, the article ends with our conclusions and demonstrates how this study contributes to an understanding of lifelong, lifewide education and how it may be useful for youth who choose to participate in this kind of programme.

Contextualising concepts of learning in education

In this article the concepts of learning and/or education are presented as formal, non-formal and informal; together, these three concepts can be considered as covering lifewide and lifelong learning (cf. Skolverket 2000; EC 2014). Learning in non-formal education is a particular focus of this study; however, in this section we will briefly explain the three concepts and how they fit together. When attempting to define non-formal learning, many facets and understandings of lifelong, lifewide learning emerge. The concept of lifewide learning refers to an understanding that learning takes place in a variety of learning settings and situations (Skolverket 2000). When lifewide learning is undertaken throughout life, it is referred to as lifelong learning (EC 2014).

From an international perspective, the values and needs of non-formal learning can be understood differently according to the various goals for the development of learning and education, which can be considered as benefiting individuals and/or organisations (Taru and Kloosterman 2013; Ahmed 2014; Harring et al. 2016). Learning and education overlap, but they can also be differentiated according to specific characteristics. According to Mark Smith, “Learning is a process that happens all the time; education involves intention and commitment” (Smith 2008 [1999], p. 8). Education can be seen as a context or setting, but the learning itself is a (lifelong) process (see also Smith 2016). According to Alan Rogers, it is possible to understand the distinction between formal, non-formal and informal learning by examining group dynamics and organisational theory: “Groups can be located on a continuum from very formal to very informal” (Rogers 2004, p. 6). Elsewhere, we have concluded from the

different and partly contradictory definitions […] that almost all of them try to connect learning or education to a place. Formal learning is associated with an institution and takes place within the formal education system. Non-formal learning is also connected to an institution (i.e. an organisation or association with a specific interest such as culture or sports) within the non-formal education system (e.g. Sports or Youth-programmes within Erasmus+) (Norqvist et al. 2016, p. 223; italics in the original).

Furthermore, informal learning is often mentioned in relation to formal and non-formal approaches; however, it differs in that informal learning does not subscribe to the systemic organisation which should characterise formal or non-formal learning (this idea has its origins in Coombs 1973 and can be further understood via, e.g., EC 2014; Harring et al. 2016). Thus, it should be noted that informal learning is not a focus of this article.

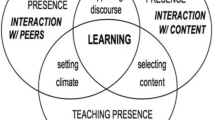

We have primarily used two perspectives in this article to offer understandings of learning in non-formal education: a learning perspective and a system perspective. Learning in EVS is part of a non-formal education system, and therefore, we consider the learning perspective alongside a perspective of the (education) system.

From a learning perspective, there is no “either/or” with regard to formal, non-formal and even informal approaches; all are part of a construct of learning which comes in various forms and takes place at various times and in various places – and all are sometimes gathered under the “umbrella” of lifelong learning (EC 2014) or understood as ubiquitous learning (Cope and Kalantzis 2009). The division of learning into formal, non-formal and informal is based on the development of these concepts in the late 1960s. Since then, they have been used with various purposes, and the importance of these concepts has fluctuated (Norqvist et al. 2016). The division of formal and non-formal learning can be understood as striving for isolation between learning concepts – otherwise known as isolated attitudes. On the other hand, if one has an attitude which considers formal and non-formal learning as already integrated – in other words, an integrated attitude – forms of learning can take place regardless of whether an individual subscribes to formal or non-formal educational systems (Norqvist et al. 2016).

From a system perspective, formal and non-formal education are not integrated, because of the difference with which each is treated (Harring et al. 2016) and financed. In Europe, formal education and non-formal education have separate budgets. In addition, the EU, which funds the non-formal EVS education programme, is not allowed to interfere with how each country organises its formal educational system (cf. EU 2012, p. 121). Hence, the division between formal and non-formal education does not rest on pedagogical arguments in which learning is at the centre.

Even though the role of the EU in how education systems are organised is clear (EU 2012), this division may cause uncertainty as both concepts are gathered under the same “umbrella” for decision making on education. The Directorate-General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) in the EU is the organisation which makes decisions about both formal and non-formal education.Footnote 3 Irrespective of whether their decisions about future education and learning rest on isolating these perspectives or on integrating policy ambitions with member countries’ views about how to organise formal and non-formal education, youth can benefit in various ways. Within a non-formal educational context and within the EU, i.e., Sweden, in this article we primarily consider the perspectives of learners, the youth volunteers, and we ask the rhetorical question of whether non-formal learning is useful for them (what we term “youthful” for youth in action).

A global perspective, with an understanding of the variety of needs of non-formal and informal learning or education, has been addressed from the 1970s onwards (cf. Coombs 1973). The concept of a community learning centre (CLC), for example, was devised to address learning in non-formal education as a means to meet local needs, which can vary between countries and regions depending on the “level” of development of the country (UNESCO Bangkok n.d.). In some countries, for example, literacy education or finding ways of alleviating poverty may be a focus, whereas in other countries, CLCs and other non-formal education initiatives aim to offer further education for those who already have a basic education up to about age 15–16 or even higher. The Kominkan CLCs of Japan represent one example of an international perspective on non-formal education which reflects the understanding that learning is divided into formal, non-formal and informal learning and can be considered to offer kinds of learning and education which are not found in schools (Sawano 2016). Kominkans are an example of learning practised throughout the Asia–Pacific region which develops education from being literacy and/or basic education towards being lifelong learning which meets new needs and new perceived values of learning and education (Ahmed 2014).

The learning perspective in an EU non-formal education programme

To better understand learning in non-formal education, EVS data were collected within the larger Youth in Action (YiA) programme. YiA, an EU-funded programme for youth conducted between 2007 and 2013, “aimed to inspire active citizenship, solidarity and tolerance and involve young people in shaping the future of the European Union” (EC n.d.). Since 2014, EVS has been included in the youth programme within Erasmus + ; Erasmus + : Youth in Action (EC 2014).Footnote 4 EVS is a non-formal education programme in which two or more organisations partner to recruit volunteers who are aged between 17 and 30 for their projects. The organisations and volunteers work in fields such as youth, sports, children, cultural heritage, culture, arts, animal welfare, environment and development cooperation (EU n.d.). At the end of their time in the EVS programme, volunteers receive a Youthpass certificate which confirms their participation and describes the projects they participated in. One aspect of the Youthpass certificate is that it confirms the learning the volunteer engaged in during their year as a volunteer. The learning is described in terms of learning outcomes and reflections on learning which are connected to the eight key competences of learning adopted by the EU in 2006 (EU 2016). The key competences are:

-

(1)

Communication in the mother tongue;

-

(2)

Communication in foreign languages;

-

(3)

Mathematical competence and basic competences in science and technology;

-

(4)

Digital competence;

-

(5)

Learning to learn;

-

(6)

Social and civic competences;

-

(7)

Sense of initiative and entrepreneurship; and

-

(8)

Cultural awareness and expression.

Volunteers are encouraged to document their learning outcomes in the Youthpass not only for their own benefit as individual learners, but also as a way of recognising non-formal (and informal) learning in youth work more generally. In this way, the Youthpass is also of benefit to organisations (EC 2005).

In 2013, when the data for this research study were collected, the YiA programme had nearly 275,000 participants engaged in 12,100 projects. EVS had nearly 10,000 volunteers participating in a non-formal learning experience lasting from 2 to 12 months. The Youthpass certificate was introduced into the YiA programme in 2007 to acknowledge learning and participation in non-formal education. It is the only official document issued by the EU as a certificate for non-formal education. The number of Youthpasses given to participants reached a milestone of 500,000 in December 2015 (EC 2015). Non-formal education in YiA, particularly in EVS, is structured in such a way that it builds on experience-based learning (Bergstein et al. 2010; Fennes et al. 2012). Applications and evaluation documents also have a structure which builds on activities undertaken by volunteers and the expected learning outcomes from those activities.

Not much research within the field of non-formal education in connection with YiA or EVS has been published. Existing publications are closer to being studies or reports rather than academic research articles. To help address this gap, this article has two primary connections to other areas of research: an impact study which focused on the Youthpass in relation to young people’s personal development, employability and the recognition of youth work (Taru and Kloosterman 2013); and published work by the RAY Network (Research-based Analysis and Monitoring of Youth in Action). The RAY Network has published a number of studies related to the content of this article, including results from surveys concerning learning in YiA. One of their reports distinguished different learning situations and methods, and stated that “experiential learning methods are applied in a considerable majority of projects” (Fennes et al. 2012, p. 7).

The European EVS programme examined in this article is an example of providing municipalities with the opportunity to form CLCs to meet the needs and values of education at a local level. The volunteers who participate are also able to develop their skills and improve their opportunities for work and employability, thus emphasising both social and economic motives for justifying non-formal education (e.g. Taru and Kloosterman 2013). This research study helps build an understanding of the usefulness of non-formal education understood from the perspectives of: a) motivation in relation to who benefits from non-formal learning; and b) formal and non-formal learning as integrated or isolated parts of lifelong and lifewide learning.

Methodology

Theoretical underpinnings

To make the collaborative discourse of learning visible, the data collection procedure for this research study was inspired by Gerry Stahl’s theories on group and collaborative cognitions (Stahl 2006, 2013). These theories present the group as a unit to analyse within learning sciences, and the outcomes of the group’s cognitions form the collaborative discourse. While individual interviews were subjective perceptions of “what learning is” at that particular moment, during training the volunteers also discussed and reflected upon similar questions. The individual and focus group viewpoints formed the collaborative discourse on the field of non-formal education with special regard to the perspective of learning, which was the object of our study. In other words, the collective data between the individual and focus group interviews (from volunteers, decision takersFootnote 5 and trainers) represent a discourse on “what learning in non-formal education is”. The outcomes describe a learning culture based on individual and group representations (for terminology of phenomena at the individual, small group and community levels, see Stahl 2013). The units of analysis for the data collected in this study were the informants’ utterances in the form of quotes.

To understand the usefulness of non-formal education, two perspectives were proposed and considered as influencing attitudes towards learning and education. The first perspective was based on motivation. We were inspired by Alice Isen and Johnmarshall Reeve (2005), and Reeve (2012), who postulated that motivation can be either extrinsic or intrinsic, depending on the autonomy of the learner. We took foremost the viewpoint of goal contents theory, which argues that intrinsic motivation in the learning process supports individuals’ motivations, which in turn influences the perceived value of the learning (see Isen and Reeve 2005; Reeve 2012). In the case of EVS, when recognition of learning in non-formal education is argued to also benefit organisations’ youth work, as in the example of the Youthpass, this could be considered as extrinsic instead of intrinsic motivation from the learners’ perspective.

Motivation for learning can also be influenced by circumstances such as whether the learning settings in a school or workplace are likely to be understood or not (Hennessey and Amabile 1998). This can then influence how non-formal education is experienced and described. When the benefit or recognition of non-formal learning is argued to be for the individual instead of for the organisation, or vice versa (cf. Smith and Clayton 2009), it may influence how individuals or organisations perceive the benefit of non-formal learning. This can be interpreted as influencing the learners’ intrinsic motivation and creativity (Hennessey and Amabile 1998; Hoff 2003). Thus, the recognition of learning, for example as documented via the Youthpass, can be seen as beneficial for either individual learners or for interests other than those of the individuals, and this may influence the perceived usefulness of the learning.

The second perspective examined the viewpoint of isolated versus integrated attitudes. Formal and non-formal learning can be seen as dichotomies, where an isolation of what is formal and what is non-formal is brought forward instead of integrated across and between formal and non-formal education (Norqvist et al. 2016). It is difficult to conclude whether it is intrinsic or extrinsic motivation that makes a learner recognise and value a learning process. A variety of theories explain the role of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation differently – sometimes with a dualistic approach, and sometimes as interwoven with each other (Reeve 2012). It is also difficult to understand whether the learning in non-formal education benefits only the individual or only the organisation. Furthermore, it is difficult to understand attitudes as being integrated or isolated in the pure sense of isolation and integration. A dualistic approach when discussing and presenting perspectives was chosen for this article, however, because it is considered to be a helpful starting point. The dualisms of the perspectives were brought forward to examine the “grey areas in between” and to further push the understanding of learning in non-formal education.

Participants and procedures

To investigate learning in non-formal education, we applied a case study approach (Cohen et al. 2007). It focused on individual actors or groups of actors and aimed for a deeper understanding of their perceptions of events (Hitchcock and Hughes 1995).

We collected data through semi-structured interviews (Kvale and Brinkmann 2009) with two different target groups. The first target group consisted of 19 volunteers participating in EVS in Sweden; the data were collected through 10 interviews with 10 individuals, and 3 interviews with focus groups of 3 people each (Cohen et al. 2007). The age of the volunteers was between 18 and 26 years, and they had come to Sweden from Albania, Belgium, Holland, England, France, Germany, Portugal, Romania and Ukraine. Eight came from a university and 7 had master’s degrees (2 had also worked for 3–4 years). Six participants came from upper secondary school, 2 came from work, and 3 had an unclear status. The individual interviews were facilitated via Skype, and the focus group interviews were administered during a midterm evaluation. The volunteers who participated took part voluntarily. They were selected because they were available at the Training centre where our research was carried out (convenience sampling) (Cohen et al. 2007). All interviews with the volunteers were conducted in English and were recorded and transcribed. The individual interviews lasted 30–60 minutes; the focus group interviews lasted about 90 minutes. Participants gave their consent to being recorded.

The second target group included 4 experts working in the Swedish context. They consisted of trainers and decision takers at a national level, i.e., connected to the fields of youth, civil society and non-formal learning with more than 15 years of experience working in these fields. They were involved in the research process to help the researchers better understand the field of non-formal learning. In addition, they helped the researchers reflect upon the volunteers’ response transcripts. The interviews with the decision takers and trainers were conducted in Swedish. This may be considered an issue, since education and learning terminology can be interpreted differently in different languages. The decision takers and trainers, however, were experienced in the field and were familiar with discussing these topics in both English and Swedish while understanding the meaning of terms in both languages.

The two authors of this article conducted the interviews. One of us (Lars Norqvist) was a trainer for on-arrival trainings and midterm evaluations.Footnote 6 This “inside perspective” was helpful because the researcher had access to material which showed each volunteer’s project during the year, including activities and expected learning outcomes. The other researcher (Eva Leffler) provided an “outside perspective”, which was beneficial as it allowed terminology or knowledge which is “taken for granted” in the field of non-formal learning to be made visible and reflected upon. Including an outside perspective was also important, as the inside perspective could increase the risk of the research being seen as biased. These two perspectives can also be viewed as investigator triangulation (Denzin 1978), especially when it comes to the analysis and understanding of the study results.Footnote 7

Findings

Presenting the data

To understand learning in non-formal education, we present our data in two parts. The first part is descriptive and shows interview quotes and summaries of the findings. In this section, the quotes are structured into 5 themes. Themes 1–4 are based on our research questions. Theme 5 can be understood as a research finding, but we decided to present it as a theme. Table 1 outlines the themes and the reasons why they were chosen to present the findings.

The second part of our data presentation utilises an analytical approach, where themes are combined, compared and discussed to address the research questions. The third research question is further addressed in a separate section of this article (in the section headed “Analysis and discussion”) to discuss the perspective of usefulness.

Some volunteers expressed more than one utterance in each part, or at times, no utterance at all. This is why the number of quotes in each part can vary and does not match the number of interviewed participants. Quotes from decision takers and trainers are translations from Swedish to English.

The presented perspectives can each be understood respectively as a theme which “at a minimum describes and organizes the possible observations and at maximum interprets aspects of the phenomenon” (Boyatzis 1998, p. 4). Quotes and data summaries represent the characteristics of each theme.

Why EVS?

Volunteers:

When the researchers asked the volunteers why they chose to take part in EVS, there were primarily two reasons given:

-

Ten explained that they wanted to get work experience and international experience which would benefit their professional life.

-

Ten explained that they wanted to travel to see another country, a kind of “organised travelling”, as expressed by one volunteer.

Two other reasons (each expressed 4 times) were that the volunteers saw a benefit in being part of an organisation, and that the cost for their year as a volunteer was funded. Others expressed their desire to join as being related to developing social skills (2 mentions), meeting other people (1), improving language (1), and challenging oneself (1). As decision takers and trainers were not participants in EVS, there are no data presenting their point of view.

How learning is described

Volunteers:

When the volunteers talked about learning in non-formal education, they described it foremost as a process connected to experience-based learning, i.e., “learning by doing”. This was expressed in 8 out of 13 interviews, as the following example describes.

I learn it more like learning by doing it and it is very good for me to [do] things, to have more experiences just to explore more things, just explore more things.

In 7 out of 10 individual interviews, and in all focus group interviews, language learning was used as an example of learning which is recognised as non-formal education.

We learn[ed] at least the language. So, now we can speak English, and I can speak Swedish.

Other examples mentioned more than once were about developing social skills (2 mentions) and getting to know oneself (2).

Decision takers and trainers:

During the interviews, 4 decision takers and trainers mentioned learning as a process; 3 of them described it as being connected to having an experience, i.e., learning by doing. One of them stressed learning about oneself.

Youthpass

Volunteers:

Over the course of the year, 2 volunteers started writing in their Youthpass during EVS. For 3 of them, it was unclear whether they had started, and 14 had not yet started. Those volunteers who had not started but intended to begin, they planned to do so at the end of their term in the EVS programme. The following dialogue makes this strategy visible.

Researcher: What are your reflections about the Youthpass in this process of EVS?

Male volunteer: Actually, we have not started at all with the Youthpass.

Female volunteer: Me, neither. You should to start?

Researcher: No, I am asking you, I mean you are the volunteers and you see –

Female volunteer: Because I know the volunteers before me, and they do it in the last week.

The Youthpass contains one section where the volunteers assess their learning outcomes and connect them to the EU’s 8 key competences (EU 2006). The trustworthiness of the Youthpass and this process of self-assessment and writing about learning outcomes were discussed in two focus group interviews where the credibility of the documented learning was questioned and expressed as being “big words on paper … that are actually not true”. One of the two volunteers who started writing in their Youthpass could see the benefit because it forced them to reflect on the learning process.

Decision takers and trainers:

The Youthpass was described by decision takers and trainers as being an instrument or tool aimed at supporting volunteers in understanding their learning. The Youthpass is considered to be a method, and the importance of documenting the learning outcomes of experiences was expressed.

Documentation

Volunteers:

The volunteers were asked whether they documented their learning or their EVS in a certain way. The documentation they mentioned included: blogs (4), notebooks/diaries (3), documents for reflection (2), photos to post on Facebook (2), objects (1), and videos (1). Two volunteers used documentation with the intention of “collecting” the learning they experienced. Others could see a connection between their documentation of learning and documents, such as blogs.

Decision takers and trainers:

There was a consensus that basically all documentation can be used as a starting point for reflecting on the process of learning. Social media were presented as a documentation tool to make learning visible. Social media are “very handy” to use, according to one decision taker.

It’s perfect to talk about learning and to express what you are doing, in the society of today, because everyone documents it, anyway. Either you have Twitter, Instagram or Facebook. You document all the time what you do. And, then you write like, “Yes, this was so much fun” … and then you have this picture on Instagram … and when you meet your mentor that supports you in the non-formal learning process … you can have it as starting point, what you already do automatically. Or you can encourage writing a diary or blog … Just like this; you already do it.

Formal versus non-formal learning

We found a comparative (and complementary) aspect of formal and non-formal learning in the data. This can be seen as a result in itself: To be able to describe and define non-formal learning, it can be compared to formal learning. Some characteristics of formal and non-formal learning were expressed by the informants in the study. Here, we present some representative quotes before we proceed to summarising the characteristics of formal and non-formal learning expressed in the data in Table 2.

Volunteer:

I think the strength of formal learning is that it seems to be quite systematic so you got somebody who will take you through the basics, the building blocks of understanding how certain fields, how certain aspects works say for example in my field … there is somebody that explains certain things, that’s great. But it doesn’t necessarily mean that you understand it. I think in the non-formal learning environment that is where we actually learn to understand it so I think they work together and they complement each other really well. I wouldn’t say that one is a substitute for the other. I think they are both really valuable learning experiences.

Decision taker and trainer:

Non-formal learning … the idea behind it is that it is planned. And, it is planned when you have a purpose in what you are doing. But, you plan it yourself. There is no one who tells you that you should learn this and that.

Analysis and discussion

In analysing the data, we combined and compared themes to present and discuss some interpretations. Themes 1 and 2 are combined because both reveal how learning is described and how volunteers describe the benefit they receive from participating in non-formal education. Themes 3 and 4 are combined because the Youthpass stresses the documentation of learning outcomes as a way of recognising non-formal education. Theme 5 is already a comparison between formal and non-formal education. In presenting our analysis and discussion, we put forth additional data to support the outcomes.

Why EVS and how learning is expressed

The organisation of non-formal learning, in the case of EVS, focuses on the learning outcomes of activities. In addition, the volunteers were encouraged to formulate expected learning outcomes in relation to the activities they would undertake. This is part of the experiential learning design of EVS, and the volunteers also described learning as an adherence to experience-based learning.

The volunteers’ explanations of why they chose EVS showed that they already had expectations about what they were supposed to learn and experience to make their year as a volunteer useful. Our analysis of the volunteers’ responses revealed that 13 of the volunteers described their reasons for joining EVS in a way which suggested they had a clear plan for why they chose to participate and what they wanted to achieve. This can be seen as the learners formalising the non-formal learning experience themselves to make its assessment possible. There were also examples in which the volunteers, regardless of support from the organisations they worked with, made sure to fulfil their own expected learning outcomes as an activity outside of EVS.

It’s more all this outside activity that we made … which make us learn a lot. Of course [what] we are making during EVS, make us also learn some stuff.

The learning they described as formal learning was exemplified through language learning. In 7 out of 10 individual interviews, and in all focus group interviews, language learning was an example of learning which was recognised as what is learned in formal education. Language learning was organised in collaboration with formal education institutions where EVS volunteers participated in the formal education programme, Swedish for Immigrants (SFI).

The outcome of this analysis led to three interpretations:

-

(1)

The non-formal education and non-formal learning in EVS are organised and designed in a way which provides learners with a “value” of non-formal education. Whether or not this value is created with the help of organisations or by the volunteers themselves does not matter. In the end, the volunteers received similar values of non-formal education.

-

(2)

Learning in non-formal education can be summarised as adhering to a socio-cultural perspective which tends significantly towards experience-based learning (Kolb 1984; Dewey 2004). This view also confirms that experience-based learning is stated as an ambition within non-formal education (Bergstein et al. 2010).

-

(3)

The integration of formal education into non-formal education benefits learners. This is exemplified through language learning (the participation in a formal education context as part of a non-formal education programme), which was discussed by many volunteers in our study.

Youthpass and documentation

Two of the 19 volunteers had started writing in their Youthpass during EVS, but most waited until the end. Mainly, they did not use the Youthpass as a process; rather, it became a summative assessment of sorts. Perhaps the volunteers simply procrastinated; but regardless, questions were raised about whether the Youthpass truly supported them in recognising their learning. If it had indeed been beneficial for the volunteers, then perhaps they might have considered writing in the Youthpass at an earlier stage in the process. Those volunteers who had started to write in their Youthpass were positive that it helped them reflect on learning. A downside to non-use of the Youthpass was that it was hard to gauge an understanding of its real value. Instead, the Youthpass became more “imaginative” and somewhat prejudiced.

Decision takers and trainers described the Youthpass as a method or tool which supports the non-formal learning process. When examining the findings, there seems to be tension between the goals of the Youthpass and how it was used in reality by the learners (volunteers). Asking whom the Youthpass benefits can reveal a possible explanation for this. Is the Youthpass used in such a way that it benefits the learner, or is it used in such a way that it benefits the recognition of organisations and youth work within the field of non-formal education? Moreover, the Youthpass can be understood as a way for the EU to formalise non-formal learning with recognised certification, a strategy which is typical for, and adopted from, formal education.

The documentation presented by the volunteers had various modalities, such as text, video, pictures and other items. Experiences were documented but not necessarily with the purpose of documenting learning. In addition, decision takers and trainers argued that social media were a “handy” starting point to demonstrate to participants of non-formal learning the activities from which they could potentially learn – in other words, a documentation of what they were already doing.

The outcome of this analysis led to two interpretations:

-

(1)

Youthpass is foremost about the recognition of organisations and youth work rather than about supporting individual learners. This is based on the fact that few learners used it, while the decision takers and trainers argued for the importance of putting experiences into words. When the volunteers were provided with a value of non-formal learning, they “just needed to write it in the Youthpass”; however, the volunteers expressed doubts about whether anyone would be interested in reading their writing.

-

(2)

When learners document what they do, these documentations of doing can also be interpreted as documentations of learning. This can be especially problematic when the learning is theoretically connected to the perspective of “learning by doing”.

Formal versus non-formal learning

The goal in comparing formal and non-formal learning is not to define the characteristics of each exactly. Indeed, the non-formal learning characteristics presented in this article can actually characterise formal learning in other contexts, and vice versa. Instead, the findings we present here are results from individuals’ subjective perceptions and cultural agreements regarding “what non-formal learning is”. The reason these concepts of non-formal and formal learning are “doomed to be compared” is because they are easily understood as dichotomies. Table 2 presents characteristics of formal and non-formal learning, and it is noteworthy that decision takers and trainers referred to this dichotomy more than the volunteers did. Possible explanations for this could be that decision takers are more used to arguing for the importance of non-formal education and are used to comparing it with formal education. Or maybe the role of the decision takers and trainers is to define and “defend” the field.

In relation to this, the concepts of formal and non-formal learning can be understood as being integrated or isolated parts of lifelong and lifewide learning, as discussed elsewhere (Norqvist et al. 2016). Examples of both integrated and isolated perspectives were shown in the data. The integrated perspectives appear in quotes expressing the view that there is no “either/or” between formal and non-formal (and informal) learning. The perception was that these kinds of learning can complement each other, even though some decision takers and trainers expressed the view that formal and non-formal education have different potential uses, and learners can benefit from combining them. The decision to name concepts as formal, non-formal and informal is from our perspective unfortunate. Instead, learners participate in various learning concepts in different ways according to their preferred style of learning.

The isolated perspectives suggested that insight into the learning process ensures that applications for funding are made on the basis that they adhere to non-formal learning policy, revealing that non-formal learning is a method of directing funding to youth. This is argued from a learning perspective; however, the reason the division is problematised was expressed by a decision taker during the interviews:

I think there are political reasons … why you use [non-formal learning]. You have to consider that it is [an] EU-programme, and that within the EU Parliament, you have to buy the whole package, and then I think that they have won at separating [formal and non-formal learning], so you can show the intrinsic value of the youth programme.

This implies that formal and non-formal learning need to be isolated into two different types of learning. This article, and the literature it is based on, however, raises the question as to whether non-formal learning concerns a specific type of learning, or a system of education where “intrinsic values” are values other than those of learning.

The outcome of this analysis led to two interpretations:

-

(1)

From the perspective of this study – the learning perspective – it is not possible to define formal, non-formal or informal as specific forms of learning which can only exist in certain forms of education. The division into various learning concepts seems to have political motives, which are not connected to education or learning as concepts. Rather, they point towards political ambitions to support youth as a group with various objectives, such as personal development and employability (Taru and Kloosterman 2013) or participation, citizenship and capacity building (Fennes et al. 2012).

-

(2)

What is formal learning and what is non-formal learning is based on individual interpretation. This in turn influences the attitude individuals have towards what is formal and non-formal learning, and what is formal and non-formal education.

The perspective of usefulness

What this article aims to highlight is the learning in non-formal education as described by learners and by decision takers and trainers. We have already addressed the first two research questions, combining themes and comparing and discussing them. In this section, we address the third research question through the perspective of usefulness: How is learning through EVS understood by various stakeholders in terms of usefulness, and for whom is it perceived to be useful? (RQ3).

Based on our data and background literature, the answer to the question of whether non-formal learning is useful for youth is that when they formulate and fulfil their own aims – under circumstances which are not likely to be understood as formal education – autonomy and intrinsic motivation (Hennessey and Amabile 1998; Isen and Reeve 2005; Reeve 2012) appear strong. When this happens, the perspective moves towards that of learning, and it appears to benefit the individuals. The integration of formal education was brought up in almost all interviews through the recognition of formal language learning (the participation in a formal education context was integrated in their non-formal education). As these elements came together in this way, the conclusion was drawn that non-formal education was useful for the individual participants, i.e., the youth. We cannot say, however, that learning in non-formal education is useful only because learning in formal education was integrated into the non-formal education experience (see Table 3).

The Youthpass works foremost as an extrinsic motivation tool, which can be interpreted as decreasing the autonomy of learners and is likely to be understood as formal education (Hennessey and Amabile 1998; Reeve 2012). This study showed that the volunteers did not always choose to use the Youthpass and did not always consider it to be useful during the learning process. Rather, most felt more or less obliged to write something in their Youthpass towards the end of their year as a volunteer. When non-formal learning is argued from a perspective of recognising organisations within youth work instead of individuals – which is one part of the recognition strategy (e.g. Taru and Kloosterman 2013) – the benefit seems to favour organisations and decision takers instead of individuals (i.e., the youth). Furthermore, when formal and non-formal learning are argued as dichotomies, the isolation between them is stressed (see Table 2). When these elements came together in this way, our conclusion was that non-formal education was more useful for organisations within youth work than for the youth themselves (see Table 3).

Table 3 presents a dualistic perspective which argues whether the non-formal education programme is more useful for either the individual learners or the organisations within youth work. This approach is a helpful starting point in understanding the dualism of the perspectives which complicate the “grey areas in between”. For instance, it might be that a non-formal learning experience can be beneficial for both the individual and the organisation; however, this cannot be taken for granted because of the complexity of the issue.

Conclusion

This article presents an ongoing mind-shift among youth. This was additionally reflected by the views of decision takers and trainers in moving from only recognising the complexity of learning as being an issue for formal education, to also recognising it as an issue for non-formal education. How learning or education is perceived by individuals influences their views on formal and non-formal education and how those education contexts can be understood and related to one another.

Non-formal education focuses on experience-based learning, i.e., learning by doing – which is discussed in this article and confirmed by other research (Fennes et al. 2012). That non-formal education more or less relies on one perspective of how to learn can be understood as a narrow point of view. Hence, with a pluralistic attitude towards learning, non-formal education has to be developed or integrated into other forms of education which provide a broader perspective on learning (Norqvist et al. 2016). Or, one has to at least be aware that when arguing for learning in non-formal education, the perspective of experience-based learning is dominant compared to other perspectives of learning (e.g. Bergstein et al. 2010). Based on our findings from this research study, it is not possible to define formal, non-formal or informal as specific forms of learning which can only exist in certain forms of education.

The learning life-worlds of young people are changing, and there are those who want education to move towards open and flexible lifelong learning systems (UNESCO 2015). The division between, and definitions of, formal and non-formal learning are, however, unclear. According to this article, it is not possible to categorise non-formal learning as being something other than formal learning. This raises the question of whether non-formal learning even exists.

The division between formal and non-formal learning can be seen as a retardation of the development of formal and non-formal education in the spirit of lifelong and lifewide learning. When learning is non-formalised, how can it connect to formal learning, or vice versa? The division of formal and non-formal (and possibly even informal) learning creates a gap between them and works against the development of interconnected education with ubiquitous learning and mobility within and across formal and non-formal education. From the perspective of seeking the usefulness of learning and education to the individual participants, this development is not in the spirit of benefiting the learners. Thus, our findings confirm that the concepts of formal and non-formal learning are complicated to use when defining learning.

From a learning perspective, this article agrees with previous research which is critical towards defining the concepts of formal and non-formal learning (Rogers 2004). We argue that current definitions of formal and non-formal education are sufficient, and leaving out concepts like formal and non-formal learning (and possibly even informal learning) can strengthen the credibility and trustworthiness of agendas or policies which promote lifewide and lifelong education. This is especially true when non-formal education which is considered useful integrates learning from both formal and non-formal education.

For education and learning to be useful for youth, challenges such as finding a balance between what is useful for organisations and what is useful for learners must be overcome. How to integrate learning which takes place within various educational systems to provide flexible and interconnected lifelong learning systems must also be addressed. If the learning perspective and the learners decide what is useful, however, learning in non-formal education, such as the experiences in the EVS non-formal education programme, could work. This article postulates that to obtain international work experience, to travel to another country, to learn through experiences, and to learn new languages, are all forms of learning which are highly valued among youth. If these expectations of learning are fulfilled, they point towards being useful for youth learning – learning which we have termed “youthful” for youth in action. Ideally, any form of education should be able to fulfil these expectations, slowly integrating and eventually erasing the borders between formal, non-formal and informal learning, at least if the learning perspective is considered first.

Notes

The “world educational crisis” was the topic of a book of the same title by American educator Philip Coombs (1968), who discerned a maladjustment between education and society. Educational systems were not transforming themselves in order to meet changing conditions in society.

Ubiquitous learning is, simplified, a state where learning is available and possible anytime and anywhere. The term is often related to ICTs and the potential of being constantly connected to the Internet.

The Directorate-General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) is the executive branch of the European Union responsible for policy on education, culture, youth, languages and sport. For more information, see http://ec.europa.eu/dgs/education_culture/index_en.htm [accessed 11 January 2017].

Now including YiA, Erasmus+ is the EU’s current programme for education, training, youth and sport, scheduled for the period 2014–2020.

The term decision takers was used because these participants had the task of taking the decisions needed when approving projects in non-formal education, based on policy and law. They also had a role in decision-making processes, i.e., formulating a basis for government decisions.

On-arrival, trainings and midterm evaluations were, and still are, mandatory for the volunteers who participated in European Voluntary Service (EVS) within the Youth in Action (YiA) programme.

The term investigator triangulation refers to pooling the results of several investigators researching the same thing. It can also be understood as a research process where perspectives from several investigators, instead of just one, are guaranteed.

References

Ahmed, M. (2014). Lifelong learning in a learning society: Are community learning centres the vehicle? In G. Carbonnier, M. Carton, & K. King (Eds.), Education, learning, training: Critical issues for development (pp. 102–125). Leiden, NL: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers.

Bergstein, R., Neven McMahon, M., & Cepin, M. (2010). Youthpass in the EVS training cycle. Bonn: Support, Advanced Learning and Training Opportunities within the Youth in Action Programme (SALTO) YOUTH Training and Cooperation Resource Centre. Retrieved 10 January 2017 from https://www.youthpass.eu/downloads/13-62-57/Publication_YP_EVS.pdf.

Boyatzis, R. (1998). Thematic analysis and code development: Transforming qualitative information. London & New Delhi: Sage.

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrisson, K. (2007). Research methods in education. London & New York: Routledge.

Coombs, P. H. (1968). The world educational crisis: A systems analysis. Paris/New York: UNESCO/Oxford University Press.

Coombs, P. H. (1973). New paths to learning for rural children and youth: Nonformal education for rural development. New York: International Council for Educational Development.

Cope, B., & Kalantzis, M. (2009). Ubiquitous learning. Exploring the anywhere/anytime possibilities for learning in the age of digital media. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press.

Denzin, N. K. (1978). The research act: A theoretical introduction to sociological methods. New York: McGraw-Hill.

Dewey, J. (2004). Democracy and education. Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://library.um.ac.id/images/stories/ebooks/Juni10/democracy320and%20education%20-%20john%20dewey.pdf.

EC (European Commission). (n.d.) Youth in action programme [webpage; online resource]. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from http://ec.europa.eu/youth/tools/youth-in-action_en.htm.

EC. (2005). Welcome to Youthpass [webpage; online resource]. Bonn: JUGEND für Europa/SALTO Training and Co-operation Resource Centre. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from https://www.Youthpass.eu/en/Youthpass/.

EC. (2013). Erasmus + : The EU programme for education, training, youth and sport 2014–2020 [slide presentation; online resource]. Brussels: European Commissoin. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from https://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/sites/erasmusplus/files/erasmus-plus-in-detail_en.pdf.

EC. (2014). Erasmus + programme guide (version 2). Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://ec.europa.eu/programmes/erasmus-plus/documents/erasmus-plus-programme-guide_en.pdf.

EC. (2015). 500,000th Youthpass certificate issued [webnews; online resource]. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from http://ec.europa.eu/youth/news/2015/1204-youth-certificate-milestone_en.htm#.

EHEA (European Higher Education Area). (2012). Making the most of our potential: Consolidating the European higher education area. Bucharest Communiqué of the EHEA Ministerial Conference [online resource]. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://opetusministerio.fi/export/sites/default/OPM/Koulutus/artikkelit/bologna/liitteet/Bucharest_Communique.pdf.

EU (European Union). (n.d.). European youth portal: Volunteering [webpage; online resource]. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from https://europa.eu/youth/eu/article/46/73_en.

EU. (2006). Recommendation of the European Parliament and of the Council of 18 December 2006 on Key Competences for Lifelong Learning (2006/962/EC). Official Journal of the European Union, L394/10. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex:32006H0962.

EU. (2012). Consolidated version of the Treaty on the functioning of the European Union. Official Journal of the European Union, C 326/47. Accessed 4 August 2016 from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:12012E/TXT&from=EN.

EU. (2016). Lifelong learning – key competences. Summary of Recommendation 2006/962/EC on key competences for lifelong learning [online resource]. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from http://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=URISERV%3Ac11090.

Fennes, H., Gadinger, S., Hagleitner, W., Lunardon, K., & Chisholm, L. (2012). Learning in Youth in Action: Results from the surveys with project participants and project leaders in May. Interim transnational analysis. Innsbruck: Research-based Analysis and Monitoring of Erasmus + : Youth in Action (RAY) Network.

Floridi, L. (2014). The fourth revolution: How the infosphere is reshaping human reality. New York: Oxford University Press.

Harring, M., Witte, M. D., & Burger, T. (2016). Informelles Lernen—Eine Einführung [Informal learning—an introduction]. In M. Harring et al. (Eds.), Handbuch informelles lernen [Handbook of informal learning]. Weinheim: Juventa/Beltz-Verlag.

Hennessey, B. A., & Amabile, T. M. (1998). Reality, intrinsic motivation, and creativity. The American Psychologist, 53(6), 674–675.

Hitchcock, G., & Hughes, D. (1995). Research and the teacher: A qualitative introduction to school-based research. London and New York: Routledge.

Hoff, E. (2003). The creative world of middle childhood: Creativity, imagination, and self-image from qualitative and quantitative perspectives. Lund: Lund University.

Isen, A. M., & Reeve, J. (2005). The influence of positive affect on intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: Facilitating enjoyment of play, responsible work behavior, and self-control. Motivation and Emotion, 29(4), 295–323.

Jahnke, I. (2016). Digital didactical designs: Teaching and learning in CrossActionSpaces. London and New York: Routledge.

Kolb, D. A. (1984). Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2009). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research Interviewing. London & New Delhi: Sage.

Norberg, A., Dziuban, C., & Moskal, P. (2011). A time based blended learning model. On the Horizon, 19(3), 207–216.

Norqvist, L., Leffler, E., & Jahnke, I. (2016). Sweden and informal learning—Towards integrated views of learning in a digital media world: A pedagogical attitude? In M. Harring et al. (Eds.), Handbuch Informelles Lernen [Handbook of informal learning] (pp. 217–235). Weinheim: Juventa/Beltz-Verlag.

Reeve, J. (2012). A self-determination theory perspective on student engagement. In S. L. Christenson et al. (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 149–172). New York: Springer.

Rogers, A. (2004). Looking again at non-formal and informal education: Towards a new paradigm. The Encyclopaedia of informal education [online resource]. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://infed.org/mobi/looking-again-at-non-formal-and-informal-education-towards-a-new-paradigm/.

Sawano, Y. (2016). Informal learning in Japan. In M. Harring et al. (Eds.), Handbuch Informelles Lernen [Handbook of informal learning] (pp. 249–259). Weinheim: Juventa/Beltz-Verlag.

Skolverket (2000). Lifelong learning and lifewide learning. Stockholm: Skolverket [National Board of Education]/Liber distribution.

Smith, M.K. (2008 [1999]). Informal learning. The encyclopaedia of informal education [online resource]. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://infed.org/mobi/informal-learning-theory-practice-and-experience/.

Smith, L. (2016). Informal learning in Australia. In M. Harring et al. (Eds.), Handbuch informelles lernen (pp. 289–300). Weinheim: Juventa/Beltz-Verlag.

Smith, L., & Clayton, B. (2009). Recognising non-formal and informal learning: Participant insights and perspectives. Adelaide: National Centre for Vocational Education Research (NCVER).

Stahl, G. (2006). Group cognition: Computer support for building collaborative knowledge. Cambridge, MA and London: MIT Press.

Stahl, G. (2013). Theories of collaborative cognition: Foundations for CSCL and CSCW together. In S. Googins, I. Jahnke, & V. Wulf (Eds.), Computer-supported collaborative learning at the workplace (pp. 43–63). Boston: Springer.

Taru, M., & Kloosterman, P. (2013). Youthpass impact study. Young people’s personal development and employability and the recognition of youth Work. Brussels: European Commission. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from https://www.Youthpass.eu/downloads/13-62-115/Youthpass%20Impact%20Study%20-%20Report.pdf.

UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization). (2015). Rethinking education. Towards a global common good? Paris: UNESCO. Retrieved 4 August 2016 from http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002325/232555e.pdf.

UNESCO Bangkok. (n.d.). Community learning centres [webpage; online resource]. Bangkok: UNESCO. Retrieved 11 January 2017 from http://www.unescobkk.org/education/literacy-and-lifelong-learning/community-learning-centres-clcs/.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to the volunteers, decision takers and trainers who took part in this study. You made this research possible and this article a reality. It has been a privilege to listen to your reflections and to learn from your views on learning in non-formal education. We would also like to express our gratitude to the reviewers of this manuscript. The constructive and guiding comments were truly helpful in the challenge of presenting a study of learning in non-formal education.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made.

About this article

Cite this article

Norqvist, L., Leffler, E. Learning in non-formal education: Is it “youthful” for youth in action?. Int Rev Educ 63, 235–256 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-017-9631-8

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-017-9631-8