Abstract

This paper studies the relationship between the business cycle and the marriage rate, using a panel data of 30 European countries for 1991 to 2018. Our results point to a pro-cyclical behavior of marriage rates, which holds after controlling for country-level observed and unobserved characteristics. We detect possible different responses of the marriage rate to the business cycle, after considering a wide range of country-level regulation affecting couples (taxation, property division, informal relationship regulations, and reproduction). Our findings suggest an important role of the cost/gain of marriage versus cohabitation/singlehood. Supplemental analysis reveals gender differences in the relationship between the business cycle and the marriage rate, depending on the previous legal marital status of the individuals. We provide additional evidence on the consequences of the pro-cyclical response of marriage rate by exploring variations in the stock of married/unmarried individuals. Results show a clear negative association between the business cycle and the stock of married individuals, but no negative response is found for the stock of those living as unmarried couples.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Sorted alphabetically, the countries included in our analysis are: Austria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Malta, Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Slovak Republic, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the United Kingdom.

Information collected from Busardò et al. 2014; Commission on European Family Law (http://ceflonline.net/country-reports-by-jurisdiction/); and the Ministry for Social Dialogue Consumer Affairs and Civil Liberties of Malta (info. on Cohabitation Law).

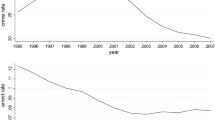

As we have defined above, the CMR is the ratio of the number of marriages during the year to the average population in that year, expressed per 1000 inhabitants.

We have used data for unemployment rates from different sources, such as the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) and the National Estimates, finding no differences in the results.

The unemployment rate as a proxy of the business cycle can also be problematic. According to Schaller (2013), this is the best indicator to capture the business cycle, although it presents some weaknesses: it can understate the magnitude of economic downturns by failing to incorporate discouraged workers.

We use as main variable of interest the total unemployment rate, but also the total female and total male unemployment rates in alternative estimates. Results are quite similar.

Country-specific quadratic time trends have also been included as a robustness check. Results do not change.

In the rest of the analysis, we only include country-specific linear trends, although results are unchanged when adding quadratic trends.

We replicate every estimate using the CMR in logarithm as dependent variable, and conclusions do not change.

We replicate every estimate using this estimator (that considers the population “at risk” of getting married), and conclusions do not change. However, since we lose almost 49% of the observations, we use the CMR as our main marriage indicator.

We use the Ravn-Uhlig rule to determine the smoothing parameter, considering that we use annual data.

Changes in the number of observations are due to the availability of information on those proxies of the business cycle dynamics.

We do not show the estimations for the cyclical components of both variables of interest because of space constraints, but results are available upon request.

Germany is also excluded from the analysis, since its current territory was part of both former territories.

Source: The World Factbook of the CIA.

Fifteen countries joined the European Union during the sample period: in 1995 (Austria, Finland and Sweden), in 2004 (Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovak Republic and Slovenia), and in 2007 (Bulgaria and Romania).

Eighteen countries adopted the common currency during the sample period: in 1999 (Austria, Belgium, Finland, France, Germany, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal and Spain), in 2001 (Greece), in 2007 (Bulgaria and Slovenia), in 2008 (Cyprus and Malta), in 2009 (Slovak Republic), and in 2011 (Estonia).

We do not have information for all countries, nor for the entire period. For this reason, the number of observations changes in Table 9.

Data come from the U.N. Statistics Division and Eurostat. Data on men and women by previous marital status (divorced, single, and widowed) have been linearly completed by the authors to avoid gaps, except for those countries to which it has not been possible to apply this technique. Results without the linear interpolation are maintained.

Of course, in the literature we can find other papers that study other determinants of the transition into and out of marriage, such as family laws (González-Val and Marcén 2012a; 2012b; 2017; 2018b; Stevenson and Wolfers 2007), parenthood (Bellido et al. 2016; Steele et al. 2005), welfare reforms (Bitler et al. 2004), demographic factors such as gender ratios or ethnicity (Angrist 2002; Bulcroft and Bulcroft 1993; Manning and Smock 2002) and even medical advances (Goldin and Katz 2002; Marcén 2015). All appear to affect the transition into and out of marriage.

Data for each country can be consulted at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/fr/web/products-eurostat-news/-/DDN-20180809-1?inheritRedirect=true&redirect=%2Feurostat%2Ffr%2Fhome.

References

Ahn, N., & Mira, P. (2002). A note on the changing relationship between fertility and female employment rates in developed countries. Journal of Population Economics, 15, 667–682.

Alesina, A., & Giuliano, P. (2007). Divorce, fertility and the value of marriage. Mimeo: Harvard University.

Amato, P., & Beattie, B. (2011). Does the unemployment rate affect the divorce rate? An analysis of state data 1960–2005. Social Science Research, 40, 705–715.

Andersson, G., Obucina, O., & Scott, K. (2015). Marriage and divorce of immigrants and descendants of immigrants in Sweden. Demographic Research, 33, 31–64.

Angrist, J. (2002). How do sex ratios affect marriage and labor markets? Evidence from America’s Second Generation. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 117, 997–1038.

Ariizumi, H., Hu, Y., & Schirle, T. (2015). Stand together or alone? Family structure and the business cycle in Canada. Review of Economics of the Household, 13, 135–161.

Baghestani, H., & Malcolm, M. (2014). Marriage, divorce and economic activity in the US: 1960–2008. Applied Economics Letters, 21, 528–532.

Becker, G. (1973). A theory of marriage: part I. Journal of Political Economy, 81, 813–846.

Bellido, H., & Marcén, M. (2019). Fertility and the business cycle: the European case. Review of Economics of the Household, 17, 1289–1319.

Bellido, H., Molina, J. A., Solaz, A., & Stancanelli, E. (2016). Do children of the first marriage deter divorce? Economic Modelling, 55, 15–31.

Bitler, M., Gelbach, J., Hoynes, H., & Zavodny, M. (2004). The impact of welfare reform on marriage and divorce. Demography, 41, 213–236.

Bulcroft, R., & Bulcroft, K. (1993). Race differences in attitudinal and motivational factors in the decision to marry. Journal of Marriage and Family, 55, 338.

Busardò, F. P., Gulino, M., Napoletano, S., Zaami, S., & Frati, P. (2014). The evolution of legislation in the field of medically assisted reproduction and embryo stem cell research in European Union members, BioMed Research International. Article ID 307160.

Chiappori, P., Iyigun, M., & Weiss, Y. (2009). Investment in schooling and the marriage market. American Economic Review, 99, 1689–1713.

Costa, D. (2000). From mill town to board room: the rise of women’s paid labor. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 14, 101–122.

Fernández, R., & Wong, J. (2014a). Divorce risk, wages and working wives: a quantitative life-cycle analysis of female labor force participation. The Economic Journal, 124, 319–358.

Fernández, R., & Wong, J. (2014b). Unilateral divorce, the decreasing gender gap, and married women’s labor force participation. American Economic Review, 104, 342–347.

Friedberg, L., & Stern, S. (2003). The economics of marriage and divorce, pp. 137–167 in “Economics Uncut: A Complete Guide to Life, Death and Misadventure” (ed. Bowmaker, S.), Edward Edgar Publishing, UK.

Goldin, C., & Katz, L. F. (2002). The power of the pill: oral contraceptives and women’s career and marriage decisions. Journal of Political Economy, 110, 730–770.

Goldstein, J., & Kenney, C. (2001). Marriage delayed or marriage forgone? New cohort forecasts of first marriage for US women. American Sociological Review, 66, 506–519.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2012a). Breaks in the breaks: an analysis of divorce rates in Europe. International Review of Law and Economics, 32, 242–255.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2012b). Unilateral divorce versus child custody and child support in the U.S. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 81, 613–643.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2017). Divorce and the business cycle: a cross-country analysis. Review of Economics of the Household, 15, 879–904.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2018a). Unemployment, marriage and divorce. Applied Economics, 50, 1495–1508.

González-Val, R., & Marcén, M. (2018b). Club classification of US divorce rates. Manchester School, 86, 512–532.

Hannemann, T., & Kulu, H. (2015). Union formation and dissolution among immigrants and their descendants in the United Kingdom. Demographic Research, 33, 273–312.

Hantrais, L., & Letabiler, M. (2014). Families and family policies in Europe. London and New York, Routledge.

Hashimoto, Y., & Kondo, A. (2012). Long-term effects of labor market conditions on family formation for Japanese youth. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies, 26, 1–22.

Hodrick, R., & Prescott, E. (1997). Postwar US business cycles: an empirical investigation. Journal of Money, Credit, and Banking, 29, 1–16.

Hoynes, H. W., Miller, D. L., & Schaller, J. (2012). Who suffers in recessions and jobless recoveries. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 26, 27–48.

Kalmijn, M. (2007). Explaining cross-national differences in marriage, cohabitation, and divorce in Europe, 1990–2000. Population Studies, 61, 243–263.

Kocourkova, J., Burcin, B., & Kucera, T. (2014). Demographic relevancy of increased use of assisted reproduction in European countries. Reproductive Health, 11, 37.

Kravdal, Ø. (2002). The impact of individual and aggregate unemployment on fertility in Norway. Demographic Research, 6, 263–294.

Lappegård, T., Klüsener, S., & Vignoli, D. (2018). Why are marriage and family formation increasingly disconnected across Europe? A multilevel perspective on existing theories. Population, Space and Place, 24, e2088.

Leridon, H., & Slama, R. (2008). The impact of a decline in fecundity and of pregnancy postponement on final number of children and demand for assisted reproduction technology. Human Reproduction, 23, 1312–1319.

Manning, W., & Smock, P. (2002). First comes cohabitation and then comes marriage? A research note. Journal of Family Issues, 23, 1065–1087.

Marcén, M. (2015). Divorce and the birth-control pill in the U.S., 1950-85. Feminist Economics, 21, 151–174.

Marcén, M., & Morales, M. (2019). Live together: does culture matter? Review of Economics of the Household, 17, 671–713.

McManus, P., & DiPrete, T. (2001). Losers and winners: the financial consequences of separation and divorce for men. American Sociological Review, 66, 246–268.

Philipov, D., & Dorbritz, J. (2003) Demographic consequences of economic transition in countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Council of Europe Publishing, 39.

Rogers, J. (2001). Price level convergence, relative prices, and inflation in Europe, Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (U.S.), International Finance Discussion Paper No. 699.

Salamaliki, P. (2017). Births, marriages, and the economic environment in Greece: empirical evidence over time. Journal of Family and Economic Issues, 38, 1–20.

Schaller, J. (2013). For richer, if not for poorer? Marriage and divorce over the business cycle. Journal of Population Economics, 26, 1007–1033.

Shore, S. (2009). For better, for worse: intra-household risk-sharing over the business cycle. Review of Economics and Statistics, 92, 536–548.

Soons, J. P., & Kalmijn, M. (2009). Is marriage more than cohabitation? Well-being differences in 30 European Countries. Journal of Marriage and Family, 71, 1141–1157.

Steele, F., Kallis, C., Goldstein, H., & Joshi, H. (2005). The relationship between childbearing and transitions from marriage and cohabitation in Britain. Demography, 42, 647–673.

Stevenson, B., & Wolfers, J. (2007). Marriage and divorce: changes and their driving forces. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 21, 27–52.

Van der Klaauw, W. (1996). Female labor supply and marital status decisions: a life-cycle model. The Review of Economic Studies, 63, 199–235.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the comments and suggestions of two anonymous referees and those of the editor, all of whom helped us to improve the quality of this work.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Bellido, H., Marcén, M. Will you marry me? It depends (on the business cycle). Rev Econ Household 19, 551–579 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09493-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11150-020-09493-z