Abstract

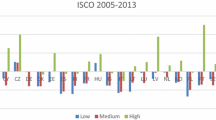

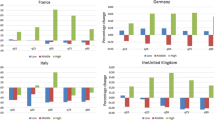

This paper performs a comparative investigation of the effects of the Great Recession on the labour market structure and wage inequality in certain countries in Southern Europe (Greece, Italy, Portugal, and Spain). By exploring the intensity of the decline of middle-skill jobs during the years 2005–2013, which makes it possible to sketch what the labour market structure has set for itself (i.e., job polarisation, upgrading or neither), the objective is to relate these changes to wage inequality and its leading determinants. Through the Recentered Influence Function regression of the Gini index on EU-SILC data, Italy is compared to each selected country in order to evaluate how much of the spatial inequality gap is accounted for by the endowment in employee characteristics (composition effect) rather than the capability of each country’s labour market to reward these characteristics (wage structure) and, second, to identify those factors that are quantitatively more significant in making differentials. In brief, Italy is less unequal than the other Southern European countries. A larger amount of its “inequality advantage” depends on the wage structure. That is, the capacity of the country’s labour market in rewarding individual endowments is more important than the ways in which they are distributed across space.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

At a journalistic level, these four troubled and heavily indebted countries of Europe are known by the acronym PIGS. This term, which was popularised during the European sovereign-debt crisis of the late 2000s, was used to indicate the inability of these countries to refinance their government debt or to bail out over-indebted banks on their own during the debt crisis (see, for example, The Independent and BBC News). However, in 2010, the use of this term was curbed because it was viewed as derogatory (see, for example, the Financial Times and Barclays Capital).

More precisely, inside the high-skill jobs, the focus is on: (1) managers and senior officials (including legislators, senior officials, managers, and corporate managers); (2) professionals (including physical, mathematical and engineering science professionals, life science, health, business, legal, and social science professionals; (3) teaching professionals; and (4) technicians and associate professionals. The middle-skill jobs focus on: (1) managers of small enterprises, (2) clerks, and (3) service workers (comprising salespersons and demonstrators, building and extraction trade workers, and metal, machinery, precision, handicraft, printing and related trades workers). Finally, low-skill jobs include: (1) agricultural and fishery workers (with other crafts and related trades personnel); (2) machine operators (including stationary plant operators, assemblers, drivers, and mobile plant operators; and (3) elementary occupations (sales and services, mining, construction, manufacturing, and transport).

Two conditions make it possible to identify the parameters of the counterfactual distribution. First, ignorability, which states that the distribution of the unobserved explanatory variables in the wage determination is the same across groups A and B; second, overlapping support, which requires that there be an overlap in observable characteristics across groups in the sense that there is no covariate such that it is only observed among individuals in group A.

As regards personal characteristics, gender (for the overall model) is a dummy with value 1 if the employee is male and 0 otherwise. Couple is a derived variable based on marital status, which is the conjugal status of each worker in relation to the marriage laws of the country, and consensual union to consider if they live in the same household. In such a way, couple has three modalities, e.g., never married, currently married sharing or not the same house (also legal spouse or registered partner or “de facto” partner), as well as others who have experienced marriage in the past (separated, divorced, widowed). Health is 1 for employees who do not suffer from any chronic illness or condition and 0 otherwise. Education attainment refers to the highest level of formal education (ISCED-97) a person has successfully completed using three categories of low (ISCED-97:0;1;2), medium (3;4), and high (5) education. Experience refers to the number of years since starting the first regular job that a person has spent at work. As regards job characteristics, the variables economic status and type of contract are dummies with value 1 if the employee is full-time (0 if part-time) and with a permanent contract (0 if temporary), respectively. The occupation type is composed of ten dummies; each of them captures a specific professional status (ISCO classification) scaled according to skill level.

For Italy, and exclusively for the year 2005, the gross wage was approximated using gross monthly income, considering the months during which the employee experienced paid employment.

References

Acemoglu, D.: Technical change, inequality, and the labor market. J. Econ. Lit. 40, 7–72 (2003)

Acemoglu, D., Autor, D.: Skills, tasks and technologies: Implications for employment and earnings. In: Ashenfelter, O., Card, D., (eds.) Handbook of Labor Econ, vol. 4B, pp. 1043–1171. Elsevier (2011)

Anghel, B., De La Rica Goiricelaya, S., Lacuesta, A.: The impact of the great recession on employment polarization in Spain. Ser. J. Span. Econ. Assoc. 5(2–3), 143–171 (2013)

Ashton, D.N., Green, F.: Education, Training and the Global Economy. Edward Elgar, London (1996)

Autor, D.: Outsourcing at will: the contribution of unjust dismissal doctrine to the growth of employment outsourcing. J. Labor Econ. 21(1), 1–42 (2003)

Autor, D.: The Polarization of Job Market Opportunities in the US. Center for American Progress, Washington, DC (2010)

Autor, D., Levy, F., Murnane, R.: The skill content of recent technological change: an empirical exploration. Q. J. Econ. 118, 1279–1333 (2003)

Ballarino, G., Braga, M., Bratti, M., Checchi, D., Filippin, A., Fiorio, C., Leonardi, M., Meschi, E., Scervini, F.: Italy: how labour market policies can foster earnings inequality. In: Nolan, W., Salverda, B., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Barsky, R., Bound, J., Charles, K., Lupton, J.: Accounting for the black-white wealth gap: a nonparametric approach. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 97(459), 663–673 (2002)

Bettio, F., Verashchagina, A.: Fiscal System and Female Employment in Europe. Fondazione G. Brodolini, Italia (2009)

Blackaby, D., Murphy, P.: Earnings, unemployment and Britain’s North-South divide: real or imaginary? Oxf. Bull. Econ. Stat. 57, 487–512 (1995)

Blinder, A.: Wage discrimination: reduced form and structural estimates. J. Hum. Resour. 8, 436–455 (1973)

Bonhomme, S., Hospido, L.: The cycle of earnings inequality: evidence from Spanish social security data. Econ. J. (2017). doi:10.1111/ecoj.12368

Breuss, F.: The crisis in retrospect: causes, effects and policy responses, routledge handbook of the economics of European integration, pp. 331–350. Routledge, London (2016)

Castellano, R., Musella, G., Punzo, G.: Structure of the labour market and wage inequality: evidence from European countries, Quality and Quantity. Springer, Berlin (2016)

Castellano, R., Punzo, G.: The role of family background in the heterogeneity of self-employment in some transition countries. Transit. Stud. Rev. 20(1), 79–88 (2013)

Chevalier, A.: Measuring overeducation. Economica 70, 509–531 (2003)

Dickey, H.: The impact of migration on regional wage inequality: a semiparametric approach. J. Reg. Sci. 54, 893–915 (2014)

DiNardo, J., Fortin, N., Lemieux T.: Labor market institutions and the distribution of wages, 1973–1993: a semi-parametric approach. Econometrica 64, 1001–1045 (1996)

Eichengreen, B., O’Rourke K.H.: What do the new data tell us, VoxEU. org, 8, (2010)

Eurofound: Preparing for the upswing: training and qualification during the crisis. European Foundation for the Improvement of Living and Working Condition, Luxembourg (2011)

Eurofound: Organisation of Working Time: Implications for Productivity and Working Conditions. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2012)

Eurofound: Employment Polarisation and Job Quality in the Crisis. European Jobs Monitor 2013. Eurofound, Dublin (2013)

Eurofound: Drivers of Recent Job Polarisation and Upgrading in Europe: European Jobs Monitor 2014. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2014)

European Commission: Employment and Social Developments in Europe 2013. Publications office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2013)

Eurostat: Educational intensity of employment and polarization in Europe and the US. Eurostat methodologies and working paper

Eurostat: Unemployment statistics—statistics explained, Luxembourg. http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Unemployment_statistics Accessed on 15 April (2015)

Fernández-Macías, E.: Job polarization in Europe? changes in the employment structure and job quality, 1995–2007. Work Occup. 39(2), 157–182 (2012)

Ferrer-I-Carbonell, A., Ramos, X., Oviedo, M.: Spain: what can we learn from past decreasing inequality. In: Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Financial Crisis Inquiry Commission: Final Report of the National Commission on the Causes of the Financial and Economic Crisis in the United States, Official Government Edition (2011)

Firpo, S., Fortin, N., Lemieux, T.: Decomposing Wage Distributions Using Recentered Influence Function Regressions. University of British Columbia, Vancouver (2007)

Firpo, S., Fortin, N., Lemieux, T.: Unconditional quantile regressions. Econometrica 77(3), 953–973 (2009)

Fortin, N., Lemieux, T., Firpo, S.: Decomposition methods in economics. Handbook Labor Econ 4, 1–102 (2011)

Gardeazabal, J., Ugidos, A.: More on identification in detailed wage decompositions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 86(4), 1034–1036 (2004)

Goos, M., Manning, A.: Lousy and lovely jobs: the rising polarization of work in Britain. Rev. Econ. Stat. 89, 118–133 (2007)

Goos, M., Manning, A., Salomons, A.: Job polarization in Europe. Am. Econ. Rev. 99, 58–63 (2009)

Grusky, D.B., Western, B., Wimer, C.: The consequences of the great recession. In: Grusky, D.B., Western, B., Wimer, C. (eds.) The Great Recession. Russell Sage Foundation, New York (2011)

Hampel, F.R.: The influence curve and its role in robust estimation. J. Am. Stat. Assoc. 69, 383–393 (1974)

Hawley, J., Otero, M.S., Duchemin, C.: Update of the European inventory on validation of non-formal and informal learning. Final Report, Cedefop (2010)

Hurley, J., Storrie, D., Jungblut, J.M.: Shifts in the Job Structure in Europe During the Great Recession. Publications Office of the European Union, Luxembourg (2015)

Hurst, E., Li, G., Pugsley, B.: Are household surveys like tax forms? evidence from income underreporting of the self-employed. Rev. Econ. Stat. 96, 19–33 (2014)

ILO: Global Wage Report 2014/15: wages and income inequality. International Labour Office Publications (2015)

International Monetary Fund: World economic outlook: adjusting to lower commodity prices. Washington (October) (2015)

Jann, B.: Oaxaca: Stata module to compute the Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition. Statistical Software Components, Boston College Department of Economics, Boston (2008)

Jenkins, S.P., Brandolini, A., Micklewright, J.: The Great Recession and the Distribution of Household Income. Oxford Scholarship Online, Oxford (2013)

Juhn, C., Murphy, K.M., Pierce, B.: Accounting for the slowdown in black–white wage convergence. In: Kosters, M.H. (ed.) Workers and Their Wages: Changing Patterns in the United States, pp. 107–143. AEI Press, Washington, DC (1991)

Juhn, C., Murphy, K., Pierce, B.: Wage inequality and the rise in returns to skill. J. Polit. Econ. 101, 410–442 (1993)

Kampelmann, S., Rycx, F.: The dynamics of task-biased technological change: the case of occupations. Bruss. Econ. Rev. 56(2), 113–142 (2013)

Katsimi, M., Moutos, T., Pagoulatos, G., Sotiropoulos, D.: Greece: the (eventual) social hardship of soft budget constraints. In: Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Keeley, B., Love, P.: From Crisis To Recovery: The Causes, Course and Consequences of the Great Recession. OECD Publishing, Paris (2010)

Krugman, P.: The Great Recession vs. The Great Depression. New York Times, New York (2009)

Machado, J.A.F., Mata, J.: Counterfactual decomposition of changes in wage distributions using quantile regression. J. Appl. Econ. 20, 445–465 (2005)

Meschi, E., Scervini, F.: A new dataset on educational inequality, Gini Discussion Paper 3, Amsterdam Institute for Advanced Labour Studies (AIAS), University of Amsterdam (2010)

Motellón, E., López-Bazo, E., El-Attar, M.: Regional heterogeneity in wage distributions: evidence from Spain. J. Reg. Sci. 51, 558–584 (2011)

Nellas, V., Olivieri, E.: Polarization trends and labour market institutions. Working papers (2015)

Oaxaca, R.: Male–female wage differentials in urban labor markets. Int. Econ. Rev. 14(3), 693–709 (1973)

Oaxaca, R., Ransom, M.R.: Identification in detailed wage decompositions. Rev. Econ. Stat. 81(1), 154–157 (1999)

OECD: Competencies for the knowledge economy. OECD Publishing, Paris (2001)

OECD: A Skilled Workforce for Strong Sustainable and Balance Growth. International Labour Office Geneva, Geneva (2010)

Parker, S.C.: The Economics of Self-Employment and Entrepreneurship. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge (2004)

Pereira, J., Galego, A.: Inter-regional wage differentials in Portugal: an analysis across the wage distribution. Reg. Stud. 48, 1529–1546 (2014)

Rodrigues, C.F., Andrade, I.: Portugal: there and back again, an inequality’s tale. In: Nolan, B., Salverda, W., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, I.G., van de Werfhorst, H. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Sicherman, N.: Overeducation in the labor market. J. Labor Econ. 9, 101–122 (1991)

Spitz-Oener, A.: Technical change, job tasks and rising educational demands: looking outside the wage structure. J. Labor Econ. 24, 235–270 (2006)

Tóth, I.G.: Revisiting grand narratives of growing inequalities: lesson from 30 country studies. In: Nolan, W., Salverda, B., Checchi, D., Marx, I., McKnight, A., Tóth, G., van de Werfhorst, H. (eds.) Changing Inequalities and Societal Impacts in Rich Countries: Thirty Countries’ Experiences. Oxford University Press, Oxford (2014)

Verloo, M.: Multiple inequalities, intersectionality and the European Union, European. J. Women’s Stud. 13(3), 211–228 (2006)

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Garofalo, A., Castellano, R., Punzo, G. et al. Skills and labour incomes: how unequal is Italy as part of the Southern European countries?. Qual Quant 52, 1471–1500 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0531-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0531-6