Abstract

Many consumers are keenly aware of gasoline prices, and consumer responses to gasoline prices have been well studied. In this paper, by contrast, we investigate how gasoline prices affect the automobile industry: manufacturers and dealerships. We estimate how changes in gasoline prices affect equilibrium prices and sales of both new and used vehicles of different fuel economies. We investigate the implications of these effects for individual auto manufacturers, taking into account differences in manufacturers’ vehicle portfolios. We also investigate effects on manufacturers’ affiliated dealership networks, including effects implied by the changes in used vehicle market outcomes.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Each bin contains approximately 20 % of vehicles in our sample period from January 1998 to June 2008. For manufacturers with multiple nameplates, Table 1 aggregates the sales across nameplates. For example, Honda contains sales of Honda and Acura vehicles; GM contains sales of Chevrolet, Buick, GMC, and Cadillac.

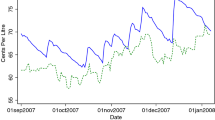

Technically, the EIA divides the country into five Petroleum Administration for Defense Districts (PADDs). Price data for the East Coast PADD is reported separately by three subdistricts (New England, Central Atlantic, and Lower Atlantic). These three subdistricts plus the four remaining districts define the geographic granularity of the gasoline price data we use.

The 25 % sample is necessary to allow for estimation of specifications with multiple sets of high-dimensional fixed effects, including fixed effect interactions, that we use later in the paper.

The 34 regions are: Baltimore/Washington, Charlotte, Cincinnati, Cleveland, Colorado, Columbus, Dakotas, Detroit, Georgia, Gulf, Hawaii, Illinois/Indiana, Indianapolis, Kansas City, Miami, Minneapolis, Missouri, Nevada, New England, New York, Norfolk/Virginia Beach, Northern California, Oklahoma, Orlando, Pennsylvania, Phoenix, Pittsburgh, San Antonio, Seattle/Portland, South Texas, Southern California, Tampa, Tennessee, and Texas. Although the regions are sometimes named after cities and sometimes after states, they represent a complete division of the country. Regions vary in both geographic size and population, but are designed to correspond to regional automobile markets.

We cannot generate a true within-customer estimate because we do not observe multiple new car purchases by the same customer. We also do not know when a trade-in was purchased because a given model year is usually available for well over a year (as long as 18 months is not uncommon). Furthermore, we cannot tell if the trade-in was originally purchased as a new or a used vehicle.

Because of the included year fixed effects, this coefficient does not measure merely changes in market tastes for high- vs. low-MPG vehicles over time. Year-to-year differences in these tastes will be absorbed by the region-specific year fixed effects (t r T ).

There are, of course, exceptions. BMW does not make a pickup truck, for example.

Note that the correct units in which to measure the rate at which a vehicle consumes gasoline is gallons per mile, which is the inverse of miles per gallon. Thus, small differences in MPG between vehicles with low MPG can have bigger implications for the number of gallons of fuel consumed per mile of travel than much larger differences in MPG among vehicles with high MPG.

Vehicle options (such a 4- vs. 6-cylinder engine) can create variation within a model in the MPG of individual vehicles. The Ward’s data do not report sales broken down by this more granular, sub-model categorization, so for models that do have such intra-model variation in MPG, we use the share of of the different sub-models sold in our transaction data to impute how many units of the model’s sales reported by Ward’s are for each sub-model. Note that this imputation will be necessary only for models whose sub-models have MPGs that fall into different bins.

For example, suppose a consumer agreed on a price of $25,000 for a new car and her trade-in was worth $10,000. If the dealer paid the consumer $10,000 for the trade-in, we would code the new vehicle price as $25,000. However, if the dealer paid the consumer only $9,000 for her trade, we would add $1,000 to the new vehicle price, now coding it as $26,000. This is because the $1,000 loss on the trade-in is an in-kind payment with the trade-in vehicle for the new vehicle and should thus be reflected in the total wealth outlay for the new car. Similarly, if the dealer paid the consumer for the trade-in in excess of the trade-in’s value, we would subtract the amount from the new vehicle price.

The $657 relative price effect between Bin 1 and Bin 5 is 2.6 % of the average new vehicle price of $25,592.

We drop from the sample vehicles with odometer readings of 150,000 miles or more; such vehicles make up 1.14 % of our sample.

There are seven vehicle segments: Compact, Midsize, Luxury, Sporty, SUV, Pickup, and Van.

The new car price specification did not require segment-specific year fixed effects to control for changing tastes: for new cars the car type fixed effects captured taste changes since each car type only sells during one model-year.

In unreported results we find that using PADDs instead of regions in this interaction does not materially change the estimates.

See Table 2 for comparisons of other demographic characteristics between new vehicle and used vehicle buyers.

Conversely, and in the extreme, an increase in demand will increase only equilibrium quantities, with no change in the price, if demand increases in a perfectly competitive market with constant marginal costs.

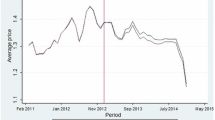

In Section 8, we investigate whether gasoline price effects differ when gasoline prices are high or low, when they are increasing or decreasing, etc. In general, we find that the estimated effects don’t vary much across these conditions.

The biggest source of used vehicles for dealerships is trade-ins, which supply 50–60 % of used vehicles.

The manufacturers headquartered in Asia are Honda, Hyundai, Mazda, Nissan, and Toyota. Those headquartered in Europe are BMW, Mercedes, and VW. Headquartered in the U.S. are Chrysler, Ford, and GM.

Note that this should not be interpreted as a full-blown counter-factual simulation such as one could obtain from a structural estimate of primitive parameters and a fully specified equilibrium model.

We would like our measure of wholesale price to capture the incremental revenue the manufacturer received when it sold the vehicle to the dealer. In order to accomplish this we define wholesale price as the invoice price for the vehicle minus the “dealer holdback” (a profit margin that the manufacturer tries to guarantee the dealer by leaving it out of the invoice price) minus any direct-to-dealer or direct-to-customer rebates the manufacturer pays when the car is sold. The dealer margin is equal to the retail price minus the wholesale price.

In an earlier draft of this paper (Busse et al. 2012), we also estimate the effect of gasoline price changes on the profitability under different assumptions on the own-price elasticities of vehicles. The results reflect the same general pattern as our revenue results.

Given that we have fixed the cut-offs for each bin, technological progress will tend to push manufacturers to higher bins independent of changes in gasoline prices, but the observed rate is much faster than that would be predicted by the results in Knittel (2011).

This consistent with Hyundai’s recent ad campaign touting the fact that they are now the most fuel efficient auto company in the U.S.

For example, comparing the U.S. firms, in 2010 35 % and 30 % of Ford and GM’s offered cars, respectively, were in either Bins 4 or 5 (high fuel economy). Only 21 % of Chrysler’s offerings were in Bins 4 or 5. At the other end of the spectrum, 26.8 % of Chrysler’s cars were in Bin 1 (low fuel economy) in 2010, compared to 15 % for Ford and 15.3 % for GM.

The automotive industry participants believe such effects exist. In an article in Automotive News on May 22, 2008 entitled “Ford: $3.50 gasoline was ‘tipping point’ for sales shift” states: “The segment shifts [away from SUVs and pickups] ‘really started to move’ when gasoline prices hit $3.50 a gallon, [Ford CEO Alan] Mulally said. ‘It seemed to us that we reached a tipping point where customers began shifting away from these vehicles at an accelerated rate,’....”

Busse et al. (2013) discuss the implications of using current gasoline prices, rather than an expectations measure such as future prices, in regressions such as those estimated in this paper.

References

Allcott, H., & Wozny, N. (2011). Gasoline prices, fuel economy, and the energy paradox. Discussion paper, New York University.

Anderson, S. T., Kellogg, R., & Sallee, J. M. (2011). What do consumers believe about future gasoline prices? Discussion Paper 16974, National Bureau of Economic Research.

Barsky, R. B., & Kilian, L. (2004). Oil and the Macroeconomy since the 1970s. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 18(4), 115–134.

Busse, M. R. (2012). When supply and demand just won’t do: using the equilibrium locus to think about comparative statics. Discussion paper, Northwestern University.

Busse, M. R., & Keohane, N. O. (2007). Market effects of environmental regulation: coal, railroads, and the 1990 clean air act. RAND Journal of Economics, 38(4), 1159–1179.

Busse, M. R., Knittel, C. R., & Zettelmeyer, F. (2012). Who is exposed to gas prices? How gasoline prices affect automobile manufacturers and dealerships. Discussion paper 18610, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge.

Busse, M. R., Knittel, C. R., & Zettelmeyer, F. (2013). Are consumers myopic? Evidence from new and used car purchases. American Economic Review, 103(1), 220–256.

Fowlie, M. (2010). Emissions trading, electricity restructuring, and investment in pollution abatement. American Economic Review, 100, 837–869.

Kahn, J. (1986). Gasoline prices and the used automobile market: a rational expectations asset price approach. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 101(2), 323–340.

Kilian, L. (2008). The economic effects of energy price shocks. Journal of Economic Literature, 46(4), 871–909.

Klier, T., & Linn, J. (2010). The price of gasoline and new vehicle fuel economy: evidence from monthly sales data. American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 2 (3), 134–153.

Knittel, C. R. (2011). Automobiles on steroids: product attribute trade-offs and technological progress in the automobile sector. American Economic Review, 101(7), 3368–3399.

Li, S., Timmins, C., & von Haefen, R. (2009). How do gasoline prices affect fleet fuel economy? American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 1(2), 113–137.

Mansur, E. T. (2007). Do oligopolists pollute less? Evidence from a restructured electricity market. Journal of Industrial Economics, 55(4), 661–689.

Sallee, J. M., West, S. E., & Fan, W. (2009). Consumer valuation of fuel economy: a microdata approach. Discussion paper, National Tax Association Conference Proceedings.

Verboven, F. (2002). Quality-based price discrimination and tax incidence—the market for gasoline and diesel cars in Europe. RAND Journal of Economics, 33(2), 275–297.

Acknowledgments

We thank John Asker, Sergio Rebelo, and Jeroen Swinkels for helpful comments. We are particularly grateful for the excellent suggestions of Alan Sorensen, and for the thoughtful and constructive contributions of two anonymous referees.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Appendix

Appendix

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Busse, M.R., Knittel, C.R., Silva-Risso, J. et al. Who is exposed to gas prices? How gasoline prices affect automobile manufacturers and dealerships. Quant Mark Econ 14, 41–95 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-016-9166-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11129-016-9166-5