Abstract

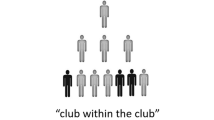

This paper investigates the organizational structure of the Hells Angels Motorcycle Club, one of the largest and best known North American motorcycle gangs. Within the first few decades since their establishment, the Angels developed a hierarchical organizational form, which allowed them to overcome internal conflict and exploit the gains from their involvement in criminal activities. This organizational form, I argue, played a central role in the rapid success of the Angels in the North American (and international) criminal landscape.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

The first victim, Marc Dub, was killed immediately by the explosion.

Below, I refer to the Hells Angels as “Angels”, “HAMC”, or simply “the club”.

In its report on organized crime to the California legislature, the California Bureau of Investigation and Intelligence, writes that “once perceived as groups of troublemakers and social rebels, [OMGs] evolved through the years into sophisticated criminal organizations” (CDOJ 2008, p. 14).

In the academic literature on outlaw bikers, these organizations are alternatively referred to as OMGs, Outlaw Motorcycle Clubs (the preferred phrasing by OMGs themselves), and “One-Percenters”.

Varese (2010) defines Organized Crime Groups (OCGs) as the result of “attempts to regulate and control the production and distribution of a given commodity or service unlawfully” (Varese 2010, 14). Varese also introduces a distinction between organized crime groups and what he refers to as Mafia groups, that is, “a type of OCG that attempts to control the supply of protection” (Varese 2010, 17).

OMGs are also very peculiar criminal organizations in that, unlike prison gangs, they do not operate

within a small, well-defined space like a correctional facility, and, unlike the mafia, they are not based on a kinship group.

The academic literature identifies alternatively four, five, and even six major North American OMGs (Barker 2005, 2007, 2010; Veno and Gannon 2009; Quinn 2001). Other than the Angels, lists usually include the Outlaws Motorcycle Club (MC), the Pagans MC, the Bandidos MC, the Sons of Silence MC, and the Mongols MC.

The AMA is the largest association of the kind in the United States.

The saloon society “traditionally consisted of places where patrons and employees tended to be armed, and no one wanted to involve the police, regardless of what occurred…. Most topless and nude bars are part of this milieu, or at least on its fringes. So are many white, blue-collar taverns and fancy nightclubs. Crimes ranging from drug sales and prostitution to murder and extortion are endemic here, although their expression may be subtle or blatant” (Quinn and Forsyth 2009, pp. 12–13).

See also Barger et al. (2001).

According to the NGIC, “Motorcycle Gangs have evolved over the past 67 years from bar room brawlers to sophisticated criminals. OMGs, which were formed in the United States, over the last 50 years have spread internationally and today… are a global phenomenon. The Hells Angels in particular stands out for its international connectivity” (NGIC 2015, p. 22).

In their analysis of more than 600 newspaper articles mentioning one or more of the four largest North American OMGs between the years 1980 and 2005, Barker and Human (2009, p. 177) find strong evidence of the HAMC’s involvement in criminal activities. During this period, the Angels had been involved in at least ten criminal incidents pertaining to the market for narcotics in the United States (including the production and distribution of methamphetamine and the distribution of cocaine), three episodes in Canada, and three episodes in Australia.

See also Barker (2010, p. 112).

“Individual chapters’ presidents usually run the day-to-day operations of their chapters, [with] important decisions made at regional, national, and international levels” (Barker 2010, p. 91).

To simplify the discussion, I assume that size is constant across chapters.

Barger et al. (2001, pp. 42–47) provide an insider’s discussion of these rules.

That is, joining the HAMC and therefore sew the Angels’ patch instead of the old patch of the club.

According to Marsden and Sher (2006, p. 40), “[petty crime] turned into professional profit-making in the late 1960s—and it transformed the organization forever. Over the next decades, drugs and crime came to define the Hells Angels around the globe”.

The Oakland chapter assumed its prominent position in the club after an internal struggle against the San Francisco chapter in 1961 (Barger et al. 2001, pp. 147–149).

So-called “Nomad Chapters being the only exception. Nomad chapters are employed to sound out the possibility of expansion into a new territory. These chapters are also exceptional in that they are not bound by the club’s rule requiring a minimum of eight members per chapter” (Marsden and Sher 2006).

According to Barger et al. (2001) in the case of one contrary vote, the dissenter is asked to motivate his decision and share the relevant information behind it. If he can convince at least one other member to change his mind, the candidacy is rejected automatically. Two contrary votes always suffice for immediate rejection. See also Veno and Gannon (2009).

Barger himself has claimed that the rule does not imply that the club “[either]sanctioned or disapproved of drug dealing by club members” and that “it’s no longer a rule” (Barger et al. 2001, pp. 46–47).

“In the major [outlaw motorcycle] clubs with large scale criminal enterprises there is virtually no way out of the organization other than death by natural causes and death because you know too much to be allowed to leave the organization. In only a handful of cases are members allowed to walk away from the club…. Those who are permitted to leave are watched carefully for the slightest sign of weakening allegiance to the club” (McGuire 1987, p. 11).

I thank the anonymous referee for pointing out this potential implication of my discussion.

“Outlaw motorcycle gangs have had close criminal associations with members of the traditional organized crime families. The La Cosa Nostra (LCN) is afforded security and transportation in narcotics deals in exchange for narcotics and contract killings. For example, the Hells Angels in New York have been criminally linked to the Gambino organized crime family; and in New York, the Buffalino family” (Richardson 1991, p. 15).

Such as the Outlaws in the Midwest, the Pagans in the Mid-Atlantic, the Bandidos in the South and North-West, and the Mongols in California.

The conflict between Mongols and Angels in Southern California is still lively today, as the Mongols have been identified as the likely responsible for the murder of the president of the HAMC San Francisco chapter (CDOJ 2008, 15).

Since 1979, the Angels have been tried repeatedly, sometimes unsuccessfully, under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, popularly known as RICO (Marsden and Sher 2006).

References

Alchian, A. A., & Demsetz, H. (1972). Production, information costs, and economic organization. American Economic Review, 62, 777–795.

Allen, D. W. (1999). Transaction costs. In B. Bouckaert & G. De Geest (Eds.), Encyclopedia of law and economics (pp. 893–926). Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Barger, S., Zimmerman, K., & Zimmerman, K. (2001). Hell’s Angel: The life and times of Sonny Barger and the Hell’s Angels motorcycle club. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Barker, T. (2005). One percent bikers clubs: A description. Trends in Organized Crime, 9, 101–112.

Barker, T. (2007). Outlaw motorcycle gangs: National and international organized crime. In J. Ruiz & D. Hummer (Eds.), Handbook of police administration (pp. 275–288). Boca Raton: CRC Press.

Barker, T. (2010). Biker gangs and organized crime. Abingdon: Routledge.

Barker, T. (2011). American based biker gangs: International organized crime. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 207–215.

Barker, T. (2012). North American criminal gangs: Street, prison, outlaw motorcycle, and drug trafficking organizations. Durham: Carolina Academic Press.

Barker, T., & Human, K. M. (2009). Crimes of the big four motorcycle gangs. Journal of Criminal Justice, 37, 174–179.

Barzel, Y. (1997). Economic analysis of property rights. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76, 169–217.

Buchanan, J. M. (1973). A defense of organized crime? In J. Rottenberg (Ed.), The economics of crime and punishment (pp. 119–132). Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute for Public Policy Research.

CDOJ. (2008). Organized crime in California: Annual report. Sacramento: California Department of Justice.

CDOJ. (2009). Organized crime in California: Annual report. Sacramento: California Department of Justice.

Cherry, P. (2005). The biker trials: Bringing down the Hells Angels. Toronto: ECW Press.

Coase, R. H. (1937). The nature of the firm. Economica, 16, 386–405.

Davis, R. H. (1982a). Outlaw motorcyclists: A problem for police, part 1. Bulletin, 51, 12–17.

Davis, R. H. (1982b). Outlaw motorcyclists: A problem for police, part 2. Bulletin, 51, 17–22.

Dobyns, J., & Johnson-Shelton, N. (2010). No angel: My harrowing undercover journey to the inner circle of the Hells Angels. New York: Broadway Books.

Droban, K. (2009). Running with the devil: The true story of the ATF’s infiltration of the Hells Angels. Guilford: The Lyons Press.

FBI. (2007). The Hells Angels. Washington, D.C.: Federal Bureau of Investigation.

Fama, E. F., & Jensen, M. C. (1983). Separation of ownership and control. The Journal of Law and Economics, 26, 301–325.

Gambetta, D. (1996). The Sicilian Mafia: The business of private protection. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Hart, O. (1989). An economist’s perspective on the theory of the firm. Columbia Law Review, 89, 1757–1774.

Holmstrom, B., & Roberts, J. (1998). The boundaries of the firm revisited. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 12, 73–94.

Klein, B., & Leffler, K. B. (1981). The role of market forces in assuring contractual performance. Journal of Political Economy, 89, 615–641.

Kostelnik, J., & Skarbek, D. (2013). The governance institutions of a drug trafficking organization. Public Choice, 156, 95–103.

Kovaleski F. S. (1998). Despite outlaw image, Hells Angels sue often. The New York Times, November 28, 2013.

Lauchs, M., Bain, A., & Bell, P. (2015). Outlaw motorcycle gangs: A theoretical perspective. New York: Springer.

Leeson, P. T. (2007). An-arrgh-chy: The law and economics of pirate organization. Journal of Political Economy, 115, 1049–1094.

Leeson, P. T. (2009). The calculus of piratical consent: The myth of the myth of social contract. Public Choice, 139, 443–459.

Leeson, P. T. (2010a). Pirational choice: The economics of infamous pirate practices. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 76, 497–510.

Leeson, P. T. (2010b). Pirates. The Review of Austrian Economics, 23, 315–319.

Leeson, P. T. (2014). Pirates, prisoners, and preliterates: Anarchic context and the private enforcement of law. European Journal of Law and Economics, 37, 365–379.

Leeson, P. T., & Rogers, D. B. (2012). Organizing crime. Supreme Court Economic Review, 20, 89–123.

Levitt, S. D., & Venkatesh, S. A. (2000). An economic analysis of a drug-selling gang’s finances. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 115, 755–789.

Marsden, W., & Sher, J. (2006). Angels of death: Inside the biker gangs’ crime empire. Boston: Da Capo Press.

McGuire, P. (1987). Outlaw motorcycle gangs: Organized crime on wheels. New York: Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms.

NGIC. (2009). National gang threat assessment. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Government Printing Office.

NGIC. (2011). National gang threat assessment. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Government Printing Office.

NGIC. (2013). National gang threat assessment. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Government Printing Office.

NGIC. (2015). National gang threat assessment. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance, US Government Printing Office.

Quinn, J. F. (2001). Angels, bandidos, outlaws, and pagans: The evolution of organized crime among the big four 1% motorcycle clubs. Deviant Behavior, 22, 379–399.

Quinn, J. F., & Forsyth, C. J. (2009). Leathers and rolexs: The symbolism and values of the motorcycle club. Deviant Behavior, 30, 235–265.

Quinn, J. F., & Forsyth, C. J. (2011). The tools, tactics, and mentality of outlaw biker wars. American Journal of Criminal Justice, 36, 216–230.

Quinn, J., & Shane Koch, D. (2003). The nature of criminality within one-percent motorcycle clubs. Deviant Behavior, 24, 281–305.

Richardson, A. (1991). Outlaw motorcycle gangs: USA overview. Washington, DC: National Institute of Justice.

SAMHSA. (2003). Summary of findings from the 2002 National Household Survey on Drug Abuse. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services.

Schelling, T. C. (1971). What is the business of organized crime? Journal of Public Law, 20, 71–84.

Skarbek, D. (2010). Putting the “con” into constitutions: The economics of prison gangs. Journal of Law Economics and Organization, 26, 183–211.

Skarbek, D. (2011). Governance and prison gangs. American Political Science Review, 105, 702–716.

Skarbek, D. (2012). Prison gangs, norms, and organizations. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 82, 96–109.

Sobel, R. S., & Osoba, B. J. (2009). Youth gangs as pseudo-governments: Implications for violent crime. Southern Economic Journal, 75, 996–1018.

The Economist. (1998). Hells angels, crime, and Canada. The Economist, March 28, 1998.

Varese, F. (2001). The Russian mafia: Private protection in a new market economy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Varese, F. (2010). What is organized crime? In F. Varese (Ed.), organized crime (pp. 1–35). Abingdon: Routledge.

Veno, A., & Gannon, E. (2009). The brotherhoods: Inside the outlaw motorcycle clubs: Full throttle edition. Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Williamson, O. E. (1983). Credible commitments: Using hostages to support exchange. The American Economic Review, 73, 519–540.

Williamson, O. E. (1985). The economic institutions of capitalism. New York: Simon and Schuster.

Williamson, O. E. (2002). The theory of the firm as governance structure: from choice to contract. The Journal of Economic Perspectives, 16, 171–195.

Wolf, D. R. (1991). The rebels: A brotherhood of outlaw bikers. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Acknowledgements

In writing this paper, I particularly benefited from comments by the Editors, an anonymous referee, Peter J. Boettke, Alexander Salter, Bryan Cutsinger, David Lucas, Julia Norgaard, Paola Suarez, Solomon Stein, and by participants at the 2016 Southern Economic Association meeting. All errors are my own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Piano, E.E. Free riders: the economics and organization of outlaw motorcycle gangs. Public Choice 171, 283–301 (2017). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0437-9

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-017-0437-9