Abstract

Elder maltreatment (EM) has been understood as a worldwide major public health threat for decades, yet it remains a form of victimization receiving limited attention, resources, and research. EM, which includes caregiver neglect and self-neglect, has far-reaching and long-lasting impacts on older adults, their families, and communities. Rigorous prevention and intervention research has significantly lagged in proportion to the magnitude of this problem. With rapidly growing population aging, the coming decade will be transformative: by 2030, one in six people worldwide will be aged 60 or older, and approximately 16% will experience at least one form of maltreatment (World Health Organization, 2021). The goal of this paper is to raise awareness of the context and complexities of EM, provide an overview of current intervention strategies based on a scoping review, and discuss opportunities for further prevention research, practice, and policy within an ecological model applicable to EM.

Similar content being viewed by others

Elder abuse, or elder maltreatment (EM), is a pressing global concern. Each year, millions of older adults experience maltreatment, and for many, the personal, financial, and societal effects are devastating and long-lasting. Despite the size and scale of this problem, rigorous prevention research and protection policies have significantly lagged in proportion to the growing prevalence of EM (Dong, 2015; Pillemer et al., 2016; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen et al., 2019; Teaster et al., 2010; Teresi et al., 2016). Researchers, policy makers, medical professionals, social and human service providers, and criminal justice advocates have attended less to victimization experienced by older adults than other age groups. To curb EM incidence and recurrence, a broad range of evidence-based interventions that are specific to mid- and later-life are urgently needed. The science of EM prevention and intervention is in its infancy, despite ongoing calls for further development, evaluation, and scale-up of effective interventions (Burnes et al., 2021, 2022; Marshall et al., 2020; Ploeg et al., 2009; Rosen et al., 2019).

Prevention science is a growing multidisciplinary field (Chilenski et al., 2020) that aims to improve public health via rigorously evaluated and disseminated interventions and policies that address malleable risk and protective factors to reduce poor outcomes or promote positive ones. Prevention scientists have made significant progress producing substantial social impact (Fishbein, 2021), but the bulk of this research has centered on prevention strategies targeted to children, youth, and their parents (e.g., substance use, parenting, child maltreatment). Preventive health initiatives are needed for adults in mid-to-later life, for whom a prevention approach has been under-utilized despite the significant potential gains.

EM is a prime example of a key opportunity for prevention scientists to expand the prevention knowledge base. Family violence, in particular, has been perceived as a problem that primarily affects youth or younger adults, despite its occurrence across the life course and its potential connections between maltreatment in early life and later life (Herrenkohl et al., 2021, 2022). Consequently, prevention research addressing child maltreatment and intimate partner violence has received far more public attention, research, and funding than EM. Prevention scientists can play a critical role in contextualizing and translating evidence to practice for preventing EM along with increasing advocacy and awareness among policymakers, practitioners, and the public. This work is vital to improving quality of life for a large, vulnerable population of older adults. As such, the aims of this paper are to (1) illustrate the scope and extent of EM, (2) provide an updated scoping review of current EM intervention research, and (3) discuss opportunities for further EM prevention and intervention research, practice, and policy within the Contextual Theory of Elder Abuse (CTEA), an emerging ecological theory relevant to EM.

The Context and Epidemiology of Elder Maltreatment

Many challenges exist within the EM field, including (a) defining abuse and the age at which adults are considered “older,” (b) determining cognitive capacity among victims and perpetrators, (c) demonstrating the intent of EM, and (d) establishing consensus on specific actions that comprise maltreatment. Balancing government intervention in protecting older victims, while respecting individual autonomy and the ethical requirement to respect adults’ rights to self-determination, along with how best to preserve family and other relationships where possible, further complicate EM prevention and intervention efforts. In addition, a consistent, standard, accepted definition for EM across agencies and state statutes has not been developed. The current universally accepted Centers for Disease Control & Prevention (CDC) definition of EM includes “abuse directed at adults aged 60 years and older as an intentional single or repeated act, by a person in a relationship with an expectation of trust” (CDC, 2021). This includes the deprivation of basic needs and omissions of care that can cause harm—or serious risk of harm—even if harm was not intended.

EM occurs in a wide variety of contexts, which highlights the unique and multifaceted nature of the problem. EM can take place in both community and facility settings, and it may involve formal or informal caregivers as well as resident-to-resident abuse in care settings. Most perpetrators are family members, acquaintances, or others with whom older victims have close interdependent relationships (Roberto, 2017; Teaster et al., 2006), which poses identification and intervention challenges. Self-neglect is also a form of EM and can cause great harm to individuals and communities, such as the loss of an older person’s rights and untimely death (Burnett et al., 2014; Mauk, 2011). The breadth of EM, as well as the distinct nature of each case, requires targeted and person-centered approaches to prevention, case assessment, and intervention.

The Prevalence of Elder Maltreatment

Multiple studies and reports have consistently established high rates of elder maltreatment (Acierno et al., 2010; National Center on Elder Abuse, n.d.; World Health Organization, 2021; Yon et al., 2017). Yon and colleagues’ (2017) frequently cited review of 52 studies across 28 countries determined that approximately one in six (15.7%) older adults experienced some form of EM. Prevalence estimates in U.S. communities range from 5 to 11% (Acierno et al., 2010; Laumann et al., 2008). Prevalence in care facility settings may be much higher; Yon and colleagues (2019) found that two-thirds of care staff reported abusive behaviors (Yon et al., 2019). Furthermore, the COVID-19 global pandemic increased risks for EM (Makaroun et al., 2020), with emerging evidence reflecting a significant increase within community and care facility settings (Chang & Levy, 2021). Prevalence statistics across studies, however, are believed highly under-estimated. Researchers are challenged to determine the full extent of harm because EM is overwhelmingly undetected and unreported. For example, some estimates indicated that only one in 24 cases of EM is ever reported and for cases of financial exploitation, in particular, only one in 44 cases is reported (Lifespan, 2011). EM is a problem that, without intervention, is predicted to escalate in proportion to population aging trends, demographic changes that will be felt within a decade. According to U.S. Census data, the 2030s will be a transformative period: the population will age considerably, population growth will slow, and the population will become more racially and ethnically diverse. By 2035, older adults will outnumber children under the age of 18 (Vespa, 2019). This permanent demographic shift highlights the urgent need for EM evidence-based interventions to improve individual outcomes and increase investment in upstream public health approaches thereby reducing downstream costs and outcomes. The personal costs of EM to older adults and families include depression, disability, long-term care placement, hospitalization, premature mortality, and suicide among other adverse outcomes (Dong, 2015). The societal costs of EM are equivalent to billions of dollars annually in direct medical costs, services provided to victims and their families, and financial loss through exploitation (MetLife Mature Market Institute, 2011). These personal and societal costs and contexts elucidate the public health imperative to identify, intervene, and ultimately prevent EM (Teaster & Hall, 2018).

Types of Elder Maltreatment

Distinct forms of EM can include physical abuse, psychological/emotional abuse, sexual abuse, financial exploitation, abandonment, caregiver neglect, and self-neglect, with some types more often examined (e.g., financial abuse) than others (e.g., sexual abuse), leaving gaps in empirical and practice understanding. Often, EM involves abuse by a perpetrator; however, one of the most challenging and harmful types of EM is self-neglect, described as:

“…an adult’s inability, due to physical or mental impairment or diminished capacity, to perform essential self-care tasks including obtaining essential food, clothing, shelter, and medical care; obtaining goods and services necessary to maintain physical health, mental health, or general safety; or managing one’s own financial affairs” (OAA Reauthorization Act, 2020).

Although self-neglect does not involve a perpetrator, it is still considered a form of EM that raises considerable health and safety concerns; furthermore, it is significantly linked to adverse health, premature mortality, and is an important risk factor for other forms of abuse (Ramsey-Klawsnik et al., 2019). Self-neglect is the most common form of EM reported to and substantiated by Adult Protective Services (APS). To illustrate, the number of self-neglect victims identified by APS is higher than all other types of abuse combined (McGee & Urban, 2021). Cases of self-neglect are more likely to involve repeat reports to APS in comparison to other forms of EM (Wangmo et al., 2014), reflecting the complexities involved in successful case resolution. Although incidence of self-neglect is high within APS, overall prevalence estimates vary based on available data and remain undetermined, in part due to problems with its identification and lack of a standard definition (Dong et al., 2011).

EM can occur once or repeatedly and can involve single or multiple perpetrators. Recent attention has focused on polyvictimization: co-occurring types of abuse, abuse over a period of time, or abuse by multiple perpetrators (Ramsey-Klawsnik, 2017; Ramsey-Klawsnik & Heisler, 2014; Teaster, 2017; Williams et al., 2020). Polyvictimization is linked to more dire consequences and outcomes than a singular form of EM. The past-year polyvictimization prevalence was 2% among a nationally representative sample of community-residing older adults in the U.S. (Williams et al., 2020). In a random population sample of older adults, Simmons and Swahnberg (2021) found that 25% of women and 28% of men reported some form of lifetime victimization, with 82% of women and 62% of men identified as polyvictims (i.e., reported experiences of more than one episode of maltreatment) who exhibited worse health outcomes. Polyvictimization cases represent a sizable proportion of APS cases and tend to be extremely challenging to resolve. In a nationwide survey, 75% of APS professionals reported that polyvictimization was present in at least 25% of their cases, while another 15% reported that polyvictimization comprised over 80% of their caseloads (Ramsey-Klawsnik & Heisler, 2014).

Risk Factors and Challenges with Detection

Most EM research has focused on identifying the prevalence and risk factors for victimization and perpetration, with far less known about the perpetrators (Roberto, 2017). Risk factors exist at multiple levels of the person-environment context; some are shared across types of maltreatment. Established risk factors for EM victimization are portrayed in Fig. 1, which represents an emerging theory for understanding EM (i.e., CTEA). Risk factors for perpetration also exist at multiple levels and include poor mental/physical health and functioning, substance abuse and misuse, low social support, limited caregiving training, emotional or financial dependence on the older victim, and history of problems with law enforcement (Anetzberger, 2005). Overall, the most consistent risk factors associated with EM seem to be limited social support and social isolation of the victim, as well as prior exposures to traumatic events (Acierno et al., 2010; Dong, 2015). Protective EM factors have not been specifically or extensively studied, although suggested potential protective factors include high cognitive functioning and access to multiple social supports and community-based resources, such as transportation services to provide older adults access to caregiver support programs (Acierno et al., 2010; Dong, 2015).

Risk factors and opportunities for intervention exist at each level of the person-environment context. 1Note: modified from Roberto and Teaster (2017). The four levels include: (1) Individual, biologic and personal factors, (2) Relationships and interactions between older adults and individuals they encounter, (3) Community and sense of place or how older adults relate within the spaces in which they live, work, or worship, (4) Broad ideological values and norms that create a climate in which abuse is normative or non-normative, and (5) Events and life transitions over time

Research on preventive interventions for EM has focused on general advocacy and education about EM, developing information helplines, providing caregiver and victim support, and attempts to enhance coordinated community services using multidisciplinary teams (Acierno et al., 2010; Burnes et al., 2022). Many efforts to increase education, awareness, training, and competency among medical staff, family caregivers, and older adults face specific challenges associated with EM identification, detection, and intervention. For instance, many older victims are unable or unwilling to report maltreatment, raising challenging ethical concerns regarding balancing right to self-determination and protecting older adults who choose to remain in unsafe relationships or environments. Medical professionals can likewise mistake signs of abuse for normative age-related changes, such as easy bruising. The fragmentation of health care systems, where older adults may be most likely to be seen, combined with limited cross-sector community partnerships between health, social, and aging services, further hinders efforts to prevent, intervene, or coordinate responses. The inadequacies in the provision of mental health services may further exacerbate the tendency for some caregivers to abuse people for whom they provide care. In short, EM is complex, multifaceted, occurs in multiple contexts across different settings (e.g., home, hospital, long-term care) and can be linked to differing risk factors from micro- to macro-levels. Addressing EM requires a multi-system effort and range of evidence-based preventive interventions specific to individual victims’ circumstances that reflect broader family and community factors that place older adults at risk for harm.

There is substantial momentum for developing, implementing, evaluating, and ultimately scaling up preventive EM interventions across primary, secondary, and tertiary stages of prevention; however, the current evidence base remains small (Teresi et al., 2016). There are some examples of primary prevention efforts (i.e., public awareness campaigns, training for health care professionals, caregiver support programs), secondary intervention efforts (i.e., shelters for victims, home evaluations), and tertiary response efforts (i.e., victim services, justice system), but the consensus within the field is that the evidence-base is sub-optimal (Burnes et al., 2021; Owusu-Addo et al., 2020; Pillemer et al., 2011; Teresi et al., 2016). More rigorous research is necessary for establishing an organized, comprehensive approach to EM prevention. It is unclear whether programs and interventions currently in operation—particularly regarding primary prevention—actually benefit those they serve (e.g., identifying interventions that are most effective, or most appropriate for different types of victims across different settings, or are the most cost-effective) (Owusu-Addo et al., 2020; Pillemer et al., 2011; Teresi et al., 2016). Thus, for the purposes of this review, we address levels of prevention broadly.

Review of Elder Maltreatment Interventions

To synthesize current EM intervention research, we briefly report results from a scoping review, exposing wide gaps in the literature. Next, we discuss opportunities and future directions integrated within Roberto and Teaster’s (2017) CTEA, which is an ecological theory for better understanding the comprehensive nature of EM.

Scoping Review Methods and Search Strategy

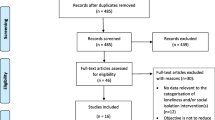

A scoping review of recent systematic and scoping review papers (also known as a scoping review-of-reviews or meta-review), related to EM intervention was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Page et al., 2021). The search was conducted in the Ebsco CINAHL, Ebsco MEDLINE, PubMed, and Proquest PsychInfo databases. Keywords included “elder” AND “abuse, maltreatment, mistreatment, or neglect” AND “scoping review or systematic review or meta-analysis or randomized controlled trial”. Keywords that included “interventions,” “prevention,” “evidence-based,” and “program” were also layered in the search. Initially, the focus was on peer-reviewed studies written in English and published in journals between 2015 and 2021 in an effort to capture growth in the field since publication of an overview of the state of EM prevention (Teresi et al., 2016) and to determine the EM interventions with the most evidence to date. Through this process, we identified a recent and similarly approached review-of-reviews that synthesized the effectiveness of interventions for EM (Marshall et al., 2020). The studies identified in our preliminary search corroborated those reported by Marshall and colleagues (2020); consequently, we elected to include their study (which represented 11 distinct systematic or scoping reviews and one meta-analysis of EM interventions) in this review and then expanded the search process for additional eligible studies within the past year (Fig. 2).

Scoping Review Results

In addition to the review-of-reviews on the effectiveness of EM interventions (Marshall et al., 2020), we identified four additional scoping/systematic reviews or meta-analysis studies (Burnes et al., 2021; Kayser et al., 2021; Shen et al., 2021; Van Royen et al., 2020) relevant to EM intervention for a total of 92 distinct studies on EM interventions represented across the five reviewed papers. Details about these studies, including key findings and recommendations, are provided in Table 1. Overall, most researchers sought to synthesize the best evidence for the effectiveness of various interventions and practices for EM prevention across diverse settings or to identify the effective measurement of outcomes and intervention assessment tools. Results revealed that EM interventions have been implemented in a variety of settings (e.g., hospitals, emergency rooms, long-term care facilities, home environments, social services) and most are related to education-based interventions to improve healthcare providers’ identification and management of EM or psychosocial interventions, such as home visits and empowerment programs targeted to older adults, family caregivers, or both.

The most common theme and conclusion across all reviewed studies is that the current evidence base regarding effective interventions is relatively weak. To date, few publications have relied on rigorous methodologies or evaluation designs (e.g., randomized controlled trials, mixed methods study designs) for reporting intervention effectiveness (Baker et al., 2017; Burnes et al., 2021; Fearing et al., 2017; Hirst et al., 2016; Marshall et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021). No “gold standard” screening tool to facilitate prevention and intervention exists for detecting and assessing EM (Kayser et al., 2021; Van Royen et al., 2020). Due to inconsistent operationalization and limited validity and reliability of measured outcomes, researchers are challenged to detect change between control and intervention groups in randomized controlled trials (Marshall et al., 2020; Ploeg et al., 2009) and are unable to pool data or compare across studies (Burnes et al., 2021).

Shen and colleagues (2021) provided some rigorous evidence from a small meta-analysis on the effectiveness of community-based psychosocial interventions, suggesting that future EM interventions target both caregivers and older adults as well as combine education and supportive services programs. This aligns with the recommendation by Burnes and colleagues (2021) that measured outcomes expand to address familial, community, and societal factors (reflecting the contextual theory below). Because multiple risk factors for EM exist, targeting multi-domain interventions may result in better outcomes. Indeed, the use of family-based models (e.g., combined education and supportive services targeting both caregivers and victims) demonstrated more promise than singular efforts (Marshall et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021). Due to the scarcity of research, there are numerous opportunities upon which to build and expand the evidence base. The complicated and multilayered nature of EM requires that it be viewed as an interaction of socioecological and transactional factors that take into account the unique needs of older adults.

Successful EM interventions must be based on sound theory and empirical evidence. As such, the CTEA (Roberto & Teaster, 2017) is offered as a way to understand empirical literature on EM prevention and intervention and to outline opportunities because it was created especially for EM and takes a holistic view of the problem, as suggested by Burnes and colleagues (2021, 2022). In the following section, we further elucidate general challenges and opportunities for prevention and intervention, using CTEA as a foundation.

Prevention, Practice, and Policy Opportunities Within the CTEA

The CTEA incorporates numerous complexities of EM within a refined model similar to Bronfenbrenner’s (1986) ecological model for the study of human development, as well as the social-ecological model promulgated by the CDC. Although the forces that contribute to the most commonly studied forms of EM (e.g., neglect, financial exploitation) may differ, Roberto and Teaster (2017) argue that factors are layered and commonly shared. In addition, consistent with findings reported in the scoping review, numerous researchers have called for a multi-domain approach to EM intervention (e.g., Burnes et al., 2021, 2022; Marshall et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021). The CTEA has broad applicability for more coherent and comprehensive EM prevention and intervention research, practice, and policy. Roberto and Teaster (2017) stress that stronger, theory-driven scholarship is critical for the refinement of study design, methodologies, and interpretation and explanation of findings.

In line with the idea of the chronosystem level in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological model, the CTEA captures the important influence of time and uniquely recognizes that older adults have long histories, and many have lives inextricably linked with their abusers, often over decades. This intersection of aging and abuse is unique to later adulthood; in contrast, child maltreatment victims have much shorter histories with their abuser(s), and they maintain a legal status as children. Adults (unless determined legally incapacitated) maintain the legal standing of an adult and have the autonomy to make decisions regarding an abusive situation. Their lives, however, are often far more intertwined with others (e.g., partners, children, informal and formal supports, governmental organizations), which may contribute to complexities inherent in EM.

The CTEA has at its center the victim, consistent with a “person-centered” approach. All environments that older adults enter and exit are essential to prevention and intervention addressing EM (Lithwick et al., 2000). Similar to the Bronfenbrenner (1986) and CDC models, this theory involves a four-level social-ecological model at individual, relational, community, and societal contexts. In applying the CTEA, the discussion begins at the macro-level (e.g., societal, community contexts) and then proceeds to the micro (e.g., relational, individual contexts). A significant challenge for EM prevention work and policy development is to address the highly influential and broad cultural and socio-structural factors that contribute to this problem. Moving beyond proximal causes to explain and intervene in occurrences of EM is one the most powerful and yet under-studied areas.

Societal Level Context and Future Considerations for EM Prevention and Intervention

The societal context of this theory comprises broad ideological values and norms that create a climate in which EM is normative or non-normative. These larger factors directly promote or inhibit EM by fostering an environment in which it might occur and thrive. Embedded within the societal context are broad power and control dynamics, including but not limited to financial markets, income, access to essential goods and services, federal and state legislation, and cultural attitudes. These factors might prevent or exacerbate older adults’ experiences of abuse or perpetrators’ inclination to abuse. The most prominent example of the societal context is ageism, a prejudice pervasive throughout the world. A large body of research demonstrates the widespread presence of and tolerance for discrimination against older people, along with numerous negative implications for health, well-being, and mortality (Chang et al., 2020). Ageism permeates all levels of the CTEA and can ultimately facilitate overt and covert abusive behaviors and hinder effective interventions due to the perpetuation of myths and negative age stereotypes that “other” older people. Common ageist stereotypes that depict older adults as frail, weak, confused, and dependent are likely a cause of EM, but there is almost no empirical research linking ageism to EM due to its ubiquitous nature, wide acceptance, and operation in conscious and unconscious ways, making it difficult to test and measure its direct impact. Support for this linkage, however, can be found in limited research, and scholars note this as an important area for further study (Pillemer et al., 2021).

Policy issues are another factor represented at the societal level. The federal response to EM is determined by four laws (i.e., Older Americans Act, Elder Justice Act, Elder Abuse Prevention and Prosecution Act, and Omnibus Reconciliation Act of 1981, which created the Social Services Block Grant) and implemented by several federal agencies (e.g., Administration for Community Living, Administration on Aging), all of which are under the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and the Department of Justice (Teaster et al., 2019). Elder justice policy at a national level has reflected a lack of comprehensive federal legislation and concomitant, consistent funding for initiatives (Teaster et al., 2010, 2019). As an example, the Child Abuse Prevention & Treatment Act (CAPTA) was originally passed in 1974, but the federal Elder Justice Act (EJA) was not passed until 2010, only after multiple attempts. Since then, the EJA has been impeded by limited discretionary spending resulting in large discrepancies in federal funding support between child protective services (CPS) and APS programs (Lu & Shelley, 2021). According to Snyder and Benson (2017), between 2008 and 2010, the federal government allocated $7.4 billion in services for all 1.25 million child maltreatment victims (averaging $5,920 per victim) and $10.9 million for all 5.7 million older adult maltreatment victims (averaging $1.92 per victim). While CPS programs have also experienced inadequate funding/support and this sizable discrepancy may not necessarily mean victim services for older adults are less sufficient, it is a stark contrast. Finally, while multiple research and training programs authorized under the Older Americans Act have influence on elder justice, the programs are chronically underfunded (Teaster et al., 2019). Inadequate funding for EM becomes even more problematic when the global pandemic has escalated its incidence (Chang & Levy, 2021; Makaroun et al., 2020) and as the older adult population is growing. Moreover, compared to child protection policy, older adult protection policy has not only been underfunded, but also has consistently lacked federal legislative and administrative direction, advocacy, well-developed diagnostic and evaluation tools, and was substantially slower to build a national EM data system. The discrepancy in attention and opportunities for research may also reflect the consequences of ageism that subtly devalue the worth of older lives.

Ageism is not just a public health problem affecting the treatment of older people but is dangerous for youth and younger adults who will ultimately internalize negative age stereotypes as they age (Chang et al., 2020). Consequently, national initiatives (e.g., FrameWorks Insititute, 2021; Reframing Aging Initiative, 2021) are invested in creating long-term social change to raise public awareness to the valuable contributions older people bring to our society and to improve the public’s perception of aging, providing a societal level opportunity for primary prevention of EM. A better understanding of later life adult development may counter ageism and lead to more supportive age-friendly policies and programs that benefit people of all ages throughout the life course. To date, the U.S. public health system, across all levels, has not prioritized the health and well-being of older adults; relatively few initiatives focus on the needs of older adults (Teaster & Hall, 2018). Much of what is understood about typical aging is portrayed as a universal period of decline, not reflective of current gerontological research. Possibly in part due to perceptions that later life is primarily a period of deficits, resilience or strengths-based approaches frequently utilized earlier in the life course, can be overlooked, despite the benefit to older adults and their communities (Madsen et al., 2019). Across sectors, there is lower overall public and governmental awareness of issues that pertain to older adults, including a focus on the intersectionality of ageism with race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, education, income level, and place (Teaster & Hall, 2018).

Although prevention and intervention efforts at this broad societal context are lacking, evidence in support of the connection between EM and ageism warrants further investigation. Unlike other EM risk factors at the individual level (e.g., age, gender, cognitive capacity), ageist attitudes are modifiable and produce EM risk at the population level. Pillemer and colleagues (2021) suggested several lines of future research, including international comparative studies examining associations between EM prevalence rates and the extent of ageism present across countries or the use of rigorous randomized controlled studies to explore the effectiveness of anti-ageism interventions on reducing EM among groups who may be at higher risk of perpetrating EM (e.g., caregivers to persons with dementia; long-term care staff).

Community Level Context and Future Considerations for EM Prevention and Intervention

The community context involves an older person’s sense of place (e.g., physical location, place of residence) and how they relate to others within that space (e.g., residing, working, socializing, and worshiping). Although the structure and culture within communities can potentially shield older adults from abuse, communities may also conceal, tacitly tolerate, or facilitate forms of EM, particularly those that do not address the problem until an egregious situation arises. On the opposite end are communities with adequate services and trained professionals dedicated to proactively supporting older adults and people with disabilities (e.g., established elder justice centers; access to Area Agencies on Aging; robust transportation options, active support groups, community centers). In addition, there are differing challenges for addressing EM in the home context with a family caregiver, versus in a nursing home context with paid caregivers, or intervening in cases of self-neglect for vulnerable adults who live alone—all of which are in need of unique, person-centered, and targeted strategies for preventing EM.

Social isolation is a significant community-level risk factor for EM victimization (Makaroun et al., 2020), illustrating the importance of community-level prevention. In part due to ageism, many older people become invisible in communities, especially those with disabilities. Older adults may spend a lot of time in their homes due to mobility or transportation challenges and may go unnoticed by others, thus increasing the risk for EM and self-neglect. A sense of community where older adults have access to services and support is critical to keeping older people visible and safe. Several studies have been conducted on education/training interventions and assessment tools for providers who work with older adults (Alt et al., 2011; Du Mont et al., 2015; Imbody & Vandsburger, 2011; Mydin et al., 2019; Van Royen et al., 2020) and while it is unclear whether these efforts actually prevent EM, they have been useful for raising EM awareness and increasing recognition of EM, also consistent with the scoping review.

Organizations that can serve a role in preventing and intervening to protect older people from maltreatment are essential to consider at the community level. APS is the social services program responsible for receiving and responding to reports of EM with the goal of maintaining safety and independence for their clients (Administration for Community Living, 2016). APS is provided by state and local government nationwide and serves older adults in the community (as well as some facility settings) and, in most states and jurisdictions, will serve vulnerable adults 18 years of age and older. Individual state statutes and county regulations determine the population that APS staff protects. The public and many professionals are largely unaware of APS, with many individuals not even knowing where to report abuse. APS is often under-funded and under-staffed; however, with no dedicated federal funds directly distributed to state APS agencies (Jackson, 2017), which highlights a vital need for more advocacy/awareness, funding, and training for APS workers and other interventionists on topics such as ageism or trauma-informed care.

Although the services that APS provides reflect a response to EM, other valuable aging services organizations play an important support role in communities and yet also remain under-recognized, such as the national network of over 600 federally funded Area Agencies on Aging (Bolkan et al., 2022). AAAs have expertise in meeting the complex social and health needs of vulnerable older adults and help to coordinate an array of home and community-based services to support older people’s independence and minimize EM risk. To date, however, there is little communication and coordination between health care agencies, social service agencies, and aging services, despite upholding multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) as the gold standard for protecting against EM. MDTs and multidisciplinary forensic centers focus primarily on responding to abuse rather than primary prevention, however, vast improvements in cross-sector partnerships (e.g., between APS, AAAs, hospitals, law enforcement) may potentially facilitate the identification of the most feasible and critical areas in which to allocate resources for building evidence-based practices that can be brought to scale for EM prevention.

Last, the promotion of livable or age-friendly initiatives (Greenfield et al., 2015) is a growing policy interest. Age-friendly communities are not just beneficial to older adults, but community members of all ages because it fosters opportunities for health, intergenerational connections, engagement, security, and accessibility for all people with varying needs and capacities. Investment in strengthening community connections, including intergenerational innovations, may be particularly helpful in addressing social isolation risk factors for EM, especially for self-neglect (Burnett et al., 2014; Ramsey-Klawsnik et al., 2019).

Relational Level Context and Future Considerations for EM Prevention and Intervention

In line with social isolation as a risk factor for EM, remaining socially active and having a large social network may be protective (Acierno et al., 2010). The relational context refers to the ability of an older adult to communicate with others as well as (1) interactions and dynamics between older adults and others, (2) social networks in relation to EM, and (3) relationships between EM victims and perpetrators. There can be many dynamics in the victim-perpetrator relationship (Roberto, 2017). Among these can be a dependence of the perpetrator on the victim (e.g., need for their money or housing), where the victim often wishes to shield the perpetrator from incarceration (especially in circumstances where the perpetrator is an adult child), and the victim may believe that an abusive relationship is better than the alternative (e.g., potentially being forced from their home to reside in a nursing home). Complex dynamics are at work when an adult is self-neglecting. There are various reasons why people self-neglect (e.g., some older adults have insight into their behaviors, some suffer from health conditions, and many have experienced significant losses or traumas). Burnett and colleagues (2006) compared a cross-section of older adults who self-neglected with those who did not and found that the former was less likely to live with others, have weekly contact with children or siblings, or visit neighbors, friends or attend religious services, underscoring the important role of social support and connectedness for prevention or intervention.

There are promising education and psychosocial-based EM interventions for caregivers, who may be at higher risk of stress and burnout, though more research is needed (e.g., see Kayser et al., 2021; Marshall et al., 2020; Shen et al., 2021). Another point of EM intervention, however, includes improved oversight and guidance for surrogate decision makers (e.g., conservatorships, guardianships, powers of attorney), which is highly inadequate. Older adults with physical and/or cognitive declines may designate (or be designated) a surrogate decision maker for making financial decisions, health care decisions, or both, typically appointing a family member (Hopp, 2000). Little is known about the outcome of surrogate decision-maker arrangements; for example, states do not keep complete figures on guardianship cases, and statutes can vary widely. Powers given to surrogate decision makers are often immense (e.g., ability to sell a person’s home/personal property, enter into contracts on their behalf, clear all medical treatments) and while they are meant to provide legal protection, there is also a risk for EM when powers go unmonitored and unnoticed. In fact, EM by surrogate perpetrators—whose job it is to manage and advocate for a protected person’s health/well-being—is a growing problem that has been highly visible nationally, with reports by the Government Accountability Office (2016), testimony before the U.S. Senate Committee on Aging and Social Security Administration (Teaster & Hall, 2018), Fourth National Guardianship Summit (2021), and media attention, in which a number of egregious high profile cases have been chronicled. Despite this public attention, documentation, and urgent need to understand the scope of these problems, to date, very little reliable empirical information exists on the nature or extent of EM by surrogate decision-maker perpetrators and their relationships with victims, compromising effective intervention efforts (Bolkan et al., 2020). Many cases of EM by surrogates go unreported and unabated for multiple reasons: elders are isolated by perpetrators (especially because of the vast powers a surrogate may have), victims may not recognize behavior as abusive, neglectful, or exploitive, or victims may remain silent due to shame, self-blame, fear of retaliation, and/or further loss of independence (Acierno et al., 2010). Victims may even feel sympathetic and protective of their perpetrator, especially if that person is a family member or codependence, substance abuse, or mental illness are involved (Ramsey-Klawsnik, 2017; Roberto, 2017).

As reflected in the scoping review, most EM intervention outcomes are attached to the victim or intervention process itself (Burnes et al., 2021), yet there is a need for additional outcomes attached to the perpetrator, victim-perpetrator relationships, and family/home/social systems. Burnes and colleagues (2022) advocated for the use of harm reduction and restorative justice approaches in cases of EM, especially where the complete severing of family relationships may only aggravate unwanted outcomes for older victims.

Individual-Level Context and Future Considerations for EM Prevention and Intervention

The individual context involves biological and personal factors of the victim, many of which are not modifiable (e.g., age, sex, gender, race/ethnicity). Other variables of particular interest that are correlated with EM include education, habilitation (e.g., community and/or long-term care settings; rural or urban geographic area), income level, physical and mental health, and cognitive capacity. Changes partially due to aging that trigger health problems may result in increased dependence on others for support and even survival, increasing the risk of EM. The aging process can also increase the risk of self-neglect, which, in turn, escalates health problems, abuse by others, and mortality, though self-neglect still lacks comprehensive research and understanding of this unique form of EM (Ramsey-Klawsnik et al., 2019). Older adults who self-neglect are often in dire situations of need and suffering from conditions such as dementia, malnutrition, dehydration, untreated medical and psychiatric problems, rodent and bug infestation, and highly dangerous environments. Fear, social isolation, and depression are among the factors that inhibit many self-neglecters from seeking or accepting support to make their lives less dangerous and more comfortable (Naik et al., 2008; Ramsey-Klawsnik et al., 2019). Important ways that individuals can protect themselves from EM at the individual level are similar to prescriptions for healthy aging in general (Rowe & Kahn, 2015), such as taking steps to protect physical, mental, and financial well-being (e.g., follow healthy patterns of eating, diet, and exercise; routine health screenings; maintain social connection; identify a trustworthy person to assist with financial and other decision-making should it become needed). Yet, despite the critical importance of planning for future care and support needs in later life, most individuals and families avoid these discussions (Bolkan et al., 2022).

Conclusions

Despite the anticipated increase in the population of older adults and the magnitude of EM, insufficient prevention measures exist, even fewer prevention programs have been systematically evaluated for their efficacy. Furthermore, EM risk is influenced by many factors that can increase or decrease risk over the life course and within specific contexts. Effective intervention and prevention strategies depend upon theory‐driven hypothesis testing in order to understand how risk factors at various levels interact in the etiology of EM. One of the most important strategies in which prevention science can engage is to work to prevent EM at all the levels addressed in the CTEA.

Prevention scientists can play a critical role in EM prevention using concerted efforts. At the societal level, efforts to combat the insidious effects of ageism are needed. One way to address ageism is to include it in discussions regarding diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts occurring in businesses, faith communities, and public and private education. Prevention at the community level can arise from a variety of resources, including community organizations that tailor activities to older adults (e.g. universities, senior centers, cooperative extension programs, faith-based community programs, volunteer organizations) and investment in age-friendly community initiatives. Adding a component specifically addressing older adults to existing activities not tailored to this age group, such as exercise programs and book clubs, also helps to keep older adults meaningfully engaged in their communities. At the relational level of EM prevention, a variety of avenues are needed to foster older adults’ socialization and reduce isolation. These opportunities are especially important as we emerge from the COVID-19 pandemic-intense years of reduced socialization and prevention efforts at this level that can ameliorate pandemic-related damage already set in motion. Additionally, effective EM prevention could be accomplished by attracting older adults to activities established to meet the needs of people of a variety of ages. Finally, at the level of the individual, strategies for healthy aging have been articulated by human development and public health scholars for decades and do not require a huge infusion of dollars to implement. Necessary to establish if and how strategies prevent EM, is the use of systematic, measurable interventions in studies employing control and comparison groups followed longitudinally. In addition, stronger integration of violence prevention across the full lifespan may generate more innovative and integrative solutions. To date, efforts to address EM have been targeted to intervention in presenting cases, while EM prevention has received far less attention. Prevention scientists are uniquely poised to remedy this important and understudied area.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [CB], upon reasonable request.

References

Acierno, R., Hernandez, M. A., Amstadter, A. B., Resnick, H. S., Steve, K., Muzzy, W., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2010). Prevalence and correlates of emotional, physical, sexual, and financial abuse and potential neglect in the United States: The National Elder Mistreatment Study. American Journal of Public Health, 100(2), 292–297. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2009.163089

Administration for Community Living. (2016). Voluntary consensus guidelines for state Adult Protective Service. US Department of Health and Human Services Administration for Community Living.

Alt, K. L., Nguyen, A. L., & Meurer, L. N. (2011). The effectiveness of educational programs to improve recognition and reporting of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 23(3), 213–233. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2011.584046

Anetzberger, G. J. (2005). The reality of elder abuse. Clinical Gerontologist, 28(1–2), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1300/J018v28n01_01

Ayalon, L., Lev, S., Green, O., & Nevo, U. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of interventions designed to prevent or stop elder maltreatment. Age and Ageing, 45(2), 216–227. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afv193

Baker, P. R., Francis, D. P., Mohd Hairi, N. N., Othman, S., & Choo, W. Y. (2017). Interventions for preventing elder abuse: Applying findings of a new Cochrane review. Age and Ageing, 46(3), 346–348. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afw186. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2467

Bolkan, C., Teaster, P., Ramsey-Klawsnik, H., & Gerow, K. (2020). Abuse of vulnerable older adults by designated surrogate decision makers. Innovation in Aging, 4(1), 702–703. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igaa057.2467

Bolkan, C., Weaver, R. H., Kim, E., & Mandal., B. (2022). Regional planning for aging in place: Older adults’ perceptions of needs and awareness of aging services in Washington State. Journal of Elder Policy, 2(2), 161–192. https://doi.org/10.18278/jep.2.1.7

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22, 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Burnes, D., MacNeil, A., Nowaczynski, A., Sheppard, C., Trevors, L., Lenton, E., Lachs, M. S., & Pillemer, K. (2021). A scoping review of outcomes in elder abuse intervention research: The current landscape and where to go next. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 57, 101476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2020.101476

Burnes, D. Connolly, M., Salvo, E., Kimball, P. F., Rogers, G., & Lewis, S. (2022). RISE: A conceptual model of integrated and restorative elder abuse intervention. The Gerontologist, gnac083, https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnac083

Burnett, J., Dyer, C. B., Halphen, J. M., Achenbaum, W. A., Green, C. E., Booker, J. G., & Diamond, P. M. (2014). Four subtypes of self-neglect in older adults: Results of a latent class analysis. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 62(6), 1127–1132. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12832

Burnett, J., Regev, T., Pickens, S., Prati, L. L., Aung, K., & Moore, J. (2006). Social networks: A profile of the elderly who self-neglect. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 18(4), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.1300/J084v18n04_05

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention. (2021). Preventing elder abuse. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.cdc.gov/violenceprevention/elderabuse/index.html

Chang, E. S., Kannoth, S., Levy, S., Wang, S. Y., Lee, J. E., & Levy, B. R. (2020). Global reach of ageism on older persons’ health: A systematic review. PLoS ONE, 15(1), e0220857. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220857

Chang, E. S., & Levy, B. R. (2021). High prevalence of elder abuse during the COVID-19 pandemic: Risk and resilience factors. The American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 29(11), 1152–1159. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2021.01.007

Chilenski, S. M., Pasch, K. E., Knapp, A., Baker, E., Boyd, R. C., Cioffi, C., Cooper, B., Fagan, A., Hill, L., Leve, L. D., & Rulison, K. (2020). The society for prevention research 20 years later: A summary of training needs. Prevention Science, 21(7), 985–1000. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01151-1

Day, A., Boni, N., Evert, H., & Knight, T. (2017). An assessment of interventions that target risk factors for elder abuse. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(5), 1532–1541. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12332

Dong, X., Simon, M., Mosqueda, L., & Evans, D. A. (2011). The prevalence of elder self-neglect in a community-dwelling population. Journal of Aging & Health, 24(3), 507–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0898264311425597

Dong, X. (2015). Elder abuse: Systematic review and implications for practice. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 63(6), 1214–1238. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.13454

Du Mont, J., Macdonald, S., Kosa, D., Elliot, S., Spencer, C., & Yaffe, M. (2015). Development of a comprehensive hospital-based elder abuse intervention: An initial systematic scoping review. PLoS ONE, 10(5), e0125105. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0125105

Fearing, G., Sheppard, C. L., McDonald, L., Beaulieu, M., & Hitzig, S. L. (2017). A systematic review on community-based interventions for elder abuse and neglect. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(2–3), 102–133. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980816000209/

Fishbein, D. (2021). The pivotal role of prevention science in this syndemic. Prevention Science, 22, 94–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-020-01180-w

FrameWorks Institute. (2021). Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/issues/aging/

Government Accountability Office. (2016). Elder abuse: The extent of abuse by guardians is unknown, but some measures exist to help protect older adult. Retrieved August 26, 2022, from https://www.gao.gov/products/GAO-17-33

Greenfield, E. A., Oberlink, M., Scharlach, A. E., Neal, M. B., & Stafford, P. B. (2015). Age-friendly community initiatives: Conceptual issues and key questions. The Gerontologist, 55(2), 191–198. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnv005

Herrenkohl, T. I., Roberto, K. A., Fedina, L., Hong, S., & Love, J. (2021). A prospective study on child abuse and elder mistreatment: Assessing direct effects and associations with depression and substance use problems during adolescence and middle adulthood. Innovation in Aging, 5(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igab028

Herrenkohl, T. I., Fedina, L., Roberto, K. A., Raquet, K., Hu, R. X., Rousson, A. N., & Mason, W. A. (2022). Child maltreatment, youth violence, intimate partner violence, and elder mistreatment: A review and theoretical analysis of research on violence across the life course. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 23(1), 314–328. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838020939119

Hirst, S. P., Penney, T., McNeill, S., Boscart, V. M., Podnieks, E., & Sinha, S. K. (2016). Best-practice guideline on the prevention of abuse and neglect of older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 35(2), 242–260. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0714980816000209

Hopp, F. P. (2000). Preferences for surrogate decision makers, informal communication, and advance directives among community-dwelling elders: Results from a national study. The Gerontologist, 40(4), 449–457.

Imbody, B., & Vandsburger, E. (2011). Elder abuse and neglect: Assessment tools, interventions, and recommendations for effective service provision. Educational Gerontology, 37(7), 634–650. https://doi.org/10.1080/15363759.2011.577721

Jackson, S. L. (2017). Adult protective services and victim services: A review of the literature to increase understanding between these two fields. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 34, 214–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2017.01.010

Kayser, J., Morrow-Howell, N., Rosen, T., Skees, S., Doering, M., Clark, S., Hurka-Richardson, D., Shams, R. B., Ringer, T., Hwang, U., & Platts-Mills, T. F. (2021). Research priorities for elder abuse screening and intervention: A Geriatric Emergency Care Applied Research (GEAR) network scoping review and consensus statement. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 33(2), 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2021.1904313

Laumann E. O., Leitsch, S. A., & Waite, L. J. (2008). Elder mistreatment in the United States: prevalence estimates from a nationally representative study. Journal of Gerontology, 63(4), S248–S254. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/63.4.S248

Lifespan. (2011). Elder abuse: Under the radar. Lifespan of Greater Rochester Inc. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from http://www.lifespanroch.org/documents/ElderAbusePrevalenceStudyRelease.pdf

Lithwick, M., Beaulieu, M., Gravel, S., & Straka, S. M. (2000). The mistreatment of older adults: Perpetrator-victim relationships and interventions. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 11(4), 95–112. https://doi.org/10.1300/J084v11n04_07

Lu, P., & Shelley, M. (2021). Comparing older adult and child protection policy in the United States of America. Ageing & Society, 41(2), 273–293. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0144686X19000990

Madsen, W., Ambrens, M., & Ohl, M. (2019). Enhancing resilience in community-dwelling older adults: A rapid review of the evidence and implications for public health practitioners. Frontiers in Public Health, 7(14). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2019.00014

Makaroun, L. K., Bachrach, R. L., & Rosland, A. (2020). Elder abuse in the time of COVID-19 – Increased risks for older adults and their caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(8), 876–880. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jagp.2020.05.017

Marshall, K., Herbst, J., Girod, C., & Annor, F. (2020). Do interventions to prevent or stop abuse and neglect among older adults’ work? A systematic review of reviews. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 32(5), 409–433. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2020.1819926

Mauk, K. L. (2011). Ethical perspectives on self-neglect among older adults. Rehabilitation Nursing, 36(2), 60–65. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2048-7940.2011.tb00067.x

McGee, L., & Urban, K. (2021). Adult maltreatment data report 2020. Submitted to the Administration for Community Living, U.S. Department of Health & Human Services.

MetLife Mature Market Institute. (2011). MetLife study of elder financial abuse: Crimes of occasion, desperation, & predation against elders. MetLife Mature Market Institute.

Moore, C., & Browne, C. (2017). Emerging innovations, best practices, and evidence-based practices in elder abuse and neglect: A review of recent developments in the field. Journal of Family Violence, 32(4), 383–397. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-016-9812-4

Mydin, F. H. M., Yuen, C., & Othman, S. (2019). The effectiveness of educational intervention in improving primary health-care service providers’ knowledge, identification, and management of elder abuse and neglect: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838019889359

Naik, A. D., Lai, J. M., Kunik, M. E., & Dyer, C. B. (2008). Assessing capacity in suspected cases of self-neglect. Geriatrics, 63(2), 24–31.

National Center on Elder Abuse. (n.d.). Research, statistics, & data. Retrieved July 11, 2021, from https://ncea.acl.gov/What-We-Do/Research/Statistics-and-Data.aspx

National Guardianship Network. (2021). Fourth national guardianship summit on maximizing autonomy & ensuring accountability: Adopted recommendations. Retrieved November 5, 2022, from https://www.guardianship.org/wp-content/uploads/Fourth-National-Guardianship-Summit-Adopted-Recommendations-May-2021-1.pdf

Older Americans Act of 1965. (as amended 2020). Washington, D.C.: Administration on Aging, Office of Human Development Services, U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare. Retrieved July 20, 2021, from https://acl.gov/about-acl/authorizing-statutes/older-americans-act

Owusu-Addo E, O’Halloran K, Birjnath, B, & Dow, B. (2020). Primary prevention interventions for elder abuse: A systematic review. Prepared for Respect Victoria on behalf of National Ageing Research Institute.

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. British Medical Journal, 372, 71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Pillemer, K., Breckman, R., Sweeney, C. D., Brownell, P., Fulmer, T., Berman, J., Brown, E., Laureano, E., & Lachs, M. S. (2011). Practitioners’ views on elder mistreatment research priorities: Recommendations from a research-to-practice consensus conference. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 23(2), 115–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2011.558777

Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., Riffin, C., & Lachs, M. S. (2016). Elder abuse: Global situation, risk factors, and prevention strategies. The Gerontologist, 56(2), S194–S205. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnw004

Pillemer, K., Burnes, D., & MacNeil, A. (2021). Investigating the connection between ageism and elder mistreatment. Nature Aging, 1, 159–164. https://doi.org/10.1038/s43587-021-00032-8

Ploeg, J., Fear, J., Hutchison, B., MacMillan, H., & Bolan, G. (2009). A systematic review of interventions for elder abuse. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 21(3), 187–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946560902997181

Ramsey-Klawsnik, H. (2017). Older adults affected by polyvictimization: A review of early research. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2017.1388019

Ramsey-Klawsnik, H., & Heisler, C. (2014). Polyvictimization in later life. Victimization of the Elderly and Disabled, 17(1).

Ramsey-Klawsnik, H., Burnett , J., & Dayton, C. (2019) . Confronting the sticky wicket of self-neglect. Administration for Community Living Project White Paper.

Reframing Aging Initiative. (2021). Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.reframingaging.org/

Roberto, K. A. (2017). Perpetrators of late life polyvictimization. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2017.1374223

Roberto, K. A., & Teaster, P. B. (2017). Theorizing elder abuse. In Elder Abuse (pp. 21–41). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47504-2_2

Rosen, T., Elman, A., Dion, S., Delgado, D., Demetres, M., Breckman, R., Lees, K., Dash, K., Lang, D., Bonner, A., Burnett, J., Dyer, C. B., Snyder, R., Berman, A., Fulmer, T., & Lachs, M. S. (2019). Review of programs to combat elder mistreatment: Focus on hospitals and level of resources needed. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society (JAGS), 67(6), 1286–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15773

Rowe, J. W., & Kahn, R. L. (2015). Successful aging 2.0: Conceptual expansions for the 21st century. The Journals of Gerontology: Series B, 70(4), 593–596. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/gbv025

Shen, Y., Sun, F., Zhang, A., & Wang, K. (2021). The Effectiveness of psychosocial interventions for elder abuse in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 679541–679541. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679541

Simmons, J., & Swahnberg, K. (2021). Lifetime prevalence of polyvictimization among older adults in Sweden, associations with ill-heath, and the mediating effect of sense of coherence. BMC Geriatrics, 21(1), 129. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-021-02074-4

Snyder, J., & Benson, W. F. (2017). Adult protective services and the long-term care ombudsman program. In X. Dong (Ed.), Elder abuse: Research, practice & policy (pp. 317–342). Springer International. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-47504-2_15

Teaster, P., & Hall, J. (Eds.). (2018). Elder abuse and the public’s health (1st edition). Springer Publishing Company.

Teaster, P. B. (2017). A framework for polyvictimization in later life. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 29(5), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2017.1375444

Teaster, P. B., Roberto, K. A., & Dugar, T. A. (2006). Intimate partner violence of rural aging women. Family Relations, 55(5), 636–648. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3729.2006.00432.x

Teaster, P. B., Wangmo, T., & Anetzberger, G. J. (2010). A glass half full: The dubious history of elder abuse policy. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 22(1–2), 6–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946560903436130

Teaster, P. B., Lindberg, B. W., & Gallo, H. B. (2019). Assessing the federal response to elder abuse, while the opioid crisis rages on. Generations, 43(4), 73–79. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33462525/

Teresi, J. A., Burnes, D., Skowron, E. A., Dutton, M. A., Mosqueda, L., Lachs, M. S., & Pillemer, K. (2016). State of the science on prevention of elder abuse and lessons learned from child abuse and domestic violence prevention: Toward a conceptual framework for research. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 28(4–5), 263–300. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2016.1240053

Van Royen, K., Van Royen, P., De Donder, L., & Gobbens, R. J. (2020). Elder assessment tools and interventions for use in the home environment: A scoping review. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 15, 1793–1807. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S261877

Vespa, J. (2019). The graying of America: More older adults than kids by 2035. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 10, 2021, from https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2018/03/graying-america.html

Wang, X. M., Brisbin, S., Loo, T., & Straus, S. (2015). Elder abuse: An approach to identification, assessment and intervention. CMAJ Canadian Medical Association Journal, 187(8), 575–581. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.141329

Wangmo, T., Teaster, P. B., Grace, J., Wong, W., Mendiondo, M. S., Blandford, C., Fisher, S., & Fardo, D. W. (2014). An ecological systems examination of elder abuse: A week in the life of Adult Protective Services. Journal of Elder Abuse & Neglect, 26(5), 440–457. https://doi.org/10.1080/08946566.2013.800463

Williams, J. L., Racette, E. H., Hernandez-Tejada, M. A., & Acierno, R. (2020). Prevalence of elder polyvictimization in the United States: Data from the national elder mistreatment study. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 35(21–22), 4517–4532. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517715604

World Health Organization. (2021). Elder abuse. Retrieved July 11, 2021, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/elder-abuse

Yon, Y., Mikton, C. R., Gassoumis, Z. D., & Wilber, K. H. (2017). Elder abuse prevalence in community settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 5(2), e147–e156. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30006-2

Yon, Y., Ramiro-Gonzalez, M., Mikton, C. R., Huber, M., & Sethi, D. (2019). The prevalence of elder abuse in institutional settings: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Public Health, 29(1), 58–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky093

Acknowledgements

We acknowledge Kathryn Ratliff, Graduate Research Assistant, and E. Carlisle Shealy, Ph.D., MPH, Assistant Director, VT Center for Gerontology for their assistance on this paper.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Ethics Approval

Not applicable.

Consent to Participate

Not applicable.

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Bolkan, C., Teaster, P.B. & Ramsey-Klawsnik, H. The Context of Elder Maltreatment: an Opportunity for Prevention Science. Prev Sci 24, 911–925 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01470-5

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-022-01470-5