Abstract

Going beyond the deeply examined non-distribution constraint, which refers to the right to residual income, the paper investigates the other side of ownership, i.e. the right to residual control, to discover a general economic rationale for what we call “democracy”: a collective decision-making method based on the principles of equality and inclusiveness. The main result of the analysis is to point to the concept of perfect democracy as an efficient solution for the provision of public goods where other allocative mechanisms, such as the marketplace, fail.

Similar content being viewed by others

Introduction

To designate organizations that do not belong to the public sector and that differ from traditional firms, we commonly talk about “nonprofit” or “third sector”. These generic expressions need a sound definition first. Salomon and Anheier (1992) provide a useful and essential description of the boundaries of such sector, arguing that nonprofit organizations require five basic characteristics, in that they have to be formal, private, non-profit distributing, self-governing and voluntary.

Consistent with this definition, it can be argued that research on the nonprofit sector needs to set for itself the ambitious goal to study, in general, all possible ways in which individuals come together on a voluntary basis to achieve common objectives that may vary from one another to a significant extent and may require widely differing governance and incentive systems. Therefore, this analysis starts by drawing a distinction among the various kinds of objectives, to associate such objectives with different ownership structures for the organization.

According to Enjorlas (2009), nonprofit and voluntary organizations may be seen as governance structures -presenting specific features in terms of formal end, ownership, residual rights, decision-making procedures, accountability, checks and balances, control procedures and embedded incentives- that facilitate collective action oriented toward public or mutual interests or toward advocacy. This paper adopts this perspective to examine, specifically, the emerging complementarities between the ownership structures for these organizations and the nature of the goods and services provided.

To do so, it will focus the analysis on a special kind of membership-based organizations engaged in activities generating, as will be shown, positive “public” externalities. Then a question is asked: which ownership structure will emerge among individuals coming together to set up a voluntary organization to pursue such public aims? Going beyond the traditional reference to the non-distribution constraint, the other side of property rights - i.e. the right to residual control - will be investigated to discover a general economic rationale for what we call “democracy”.

The “public” nature of nonprofit supply

As it has just been notes, the nature of the aims pursued by third sector organizations can be extremely extensive and diversified, requiring different incentive structures to achieve efficiently the intended objectives. Beyond this crucial theoretical aspect, it is worthwhile to distinguish between different kinds of organizational objectives also in terms of policy prescriptions, as these objectives may be more or less worthy of different kinds of government and tax incentives.

Focusing on the nature of the goods and services provided, the main theories suggest that nonprofit firms arise as institutional solutions to market and government failures (Rose-Ackerman 1986). In his classical work, Weisbrod (1975) points out that the private provision of public goods can be seen as the economic rationale for such organizations, financed by people dissatisfied with the level of public goods supplied by government. His analysis focuses mainly on collective-consumption goods, but he seems to extend nonprofit activities to other government provided goods defined as “preferred private goods”. In particular, he refers to goods that can be sold in private markets but that nonprofits may wish to make available to some consumers regardless of their ability to pay, as in the case of educational services (Weisbrod 1998).

An interesting frame of reference to understand the nature of supply is that put forward by Gui (1993), who classifies economic micro-organizations by making a distinction between a dominant category and a beneficiary category of stakeholders. According to this approach, unlike for-profit or capitalist organizations, the beneficiaries of third sector organizations are not the investors. As he draws the limit with respect to traditional firms, Gui makes a further distinction within third sector organizations. He refers to mutual benefits when the dominant category and the beneficiary category merge. This situation applies in most cases considered by traditional economic theories. On the other hand, when both categories diverge, we are in the presence of so-called public benefits. In this case, the dominant category is made up generally of donors while beneficiaries include various classes of agents. According to this approach, only the latter should be considered true nonprofit organizations while there would be no point in setting a non-distribution constraint for mutual benefits.

The existence of public benefit organizations shows that, by subsidizing the consumption of others, there are individuals willing to pay for goods and services that they do not use directly. Such propensity, which is quite common in reality, can be explained by reference to the concept of existence value, which is also known as “passive-use value”. This concept was originally introduced by Krutilla (1967) to attribute economic value to things that cannot be easily priced, such as environmental resources. The passive-use value is the price that an individual is willing to pay for the production or conservation of a good regardless of its use or consumption. It calls to mind the concept of “merit good”, which is a good that provides benefits to both its users as well as, in keeping with the values prevailing in the community at large, those that do not use it directly (Musgrave 1987).

Even though this definition of willingness to pay makes no reference, at least not openly, to forms of subsidy for the consumption of others, there is a basic analogy that should be considered. In fact, the adoption of the concept of passive-use value makes it possible to extend the so-called “set of valuers” to a vaster range of individuals than that which includes only the users of the good (Carson et al. 1999). In other words, the possibility is accepted that there are individuals, other than consumers, who might derive a benefit from certain goods and this has significant implications for the understanding of many realities that are part of the third sector. Suffice to think of the voluntary provision of charitable goods, i.e. goods that benefit users other than those who pay for them, or to specific kinds of services, such as childcare, medical care, education and care for the aged: even though they are private, as people other than the beneficiaries are interested in the level of quality of such services, they imply a public good element (Francois 2003).

To this end, it is worthwhile to consider Rose-Ackerman’s (1996) classical viewpoint, whereby nonprofit firms should be founded by ideological individuals defined as people who “feel pleasure when an idea they support is reified in a service-providing or advocacy organization” (p. 717). This definition again calls to mind an intrinsic value, independent of consumption, which can be seen as the lowest common denominator of this kind of supply, supporting the idea that such services, such as those just mentioned, are all characterized by a public good element to the extent that individuals, other than consumers, are interested in their level or quality.

Thus, starting from Weisbrod’s perspective on public goods, a broader definition of public goods can be given based on a minimum requirement, that is that the two essential properties of non-excludability and equal availability identified by Samuelson (1954; 1955) should apply to at least one aspect, including the above-mentioned passive-use value. So, public benefits will be considered in an extensive sense, too, as nonprofit organizations engaged in activities generating positive public externalities in many ways. This approach appears perfectly consistent with some of the main theories about nonprofit organizations which often assume, directly or indirectly, a willingness to pay not related to the dimension of consumption.Footnote 1 To deny this phenomenon would mean to exclude from economic analysis the most emblematic and probably most significant - including from a quantitative point of view - organizations of the third sector.

Talking about public goods implies necessarily taking into account the free riding problem. For the sake of argument, one can consider many reasons why individuals participate voluntarily in the production of public goods of this nature. Emphasis is placed on Arrow’s illuminating and exhaustive analysis (1975) related to the case of voluntary blood giving that can be easily extended to the kind of goods and services examined. First, he refers to a sort of altruism whereby the welfare of each individual will depend both on his own satisfaction and on the satisfactions of others. Alternatively, he considers that the welfare of an individual can depend not only on what is good for himself and others but also on his contributions to the welfare of others. Lastly, he refers to the possibility that the choices of individuals are sometimes determined by the intention to abide by rules perceived as fair and capable of leading, if followed by everyone, to a Pareto-efficient situation, such as that of the production of a public good. In this sense, Arrow refers to ethical standards related to Rawls’s theory of justice and Kant’s moral imperatives.

There is a research strand in experimental economics that investigated the psychological reasons of a phenomenon commonly observed in reality. In fact, several experiments showed that in many cases, even though they are generally lower than necessary to achieve Pareto-efficiency, individual contributions to a public good are always greater than contemplated by traditional theory.Footnote 2 To that end, several hypotheses were investigated, including the propensity to reciprocity (Sugden 1984) and other forms of selective incentives (Olson 1965), such as the quest for social recognition and the tendency to affirm one’s identity or to reinforce a sense of belonging.Footnote 3

Whatever the reasons that drive some people to contribute voluntarily to the production of a public good, there is a need to combine all the resources that are potentially available for this purpose, as some individuals might refrain from contributing due to the lack of reliable counterparties capable of guaranteeing the proper use of the resources gathered. In the next paragraph this problem will be approached by focusing on the optimal ownership structure for private organizations engaged in the provision of such kind of goods and services.

The organization’s ownership structure

In the preceding paragraph a general criterion was identified to give an overview of public benefit nonprofits as opposed, for example, to third sector organizations that pursue - in a mutual way - private benefits for their members. Now, it’s useful to investigate the complementarities between the nature of supply and the decision-making procedures spontaneously adopted by private organizations engaged in production. To do so, attention is shifted from the deeply examined non-distribution constraint to the other side of ownership. In fact, according to the traditional theory of the firm (Williamson 1975; Grossman and Hart 1986; Hart and Moore 1990), ownership of an organization can be defined as the holding of two “residual” rights: the right to the residual income resulting from the organization’s activities, after deducting all contractual costs, and the right to residual control, i.e. the right to make decisions in situations not covered by contracts.

The non-distribution constraint obviously refers to the right to residual and its importance has been stressed first by Hansmann (1980). According to his analysis, nonprofit firms arise in sectors where, for some reasons, it is difficult for the purchaser to evaluate the good or service sold. Such firms are established as a result of the non-distribution constraint which acts as a signal to assure people that quality will not be sacrificed for private monetary gain. He specifically examines the case of voluntary contribution to local public broadcasting stations in the United States and the example of charity organizations, financed by personal contributions, dedicated to providing help to needy individuals: interestingly, both cases represent well the public nature of nonprofit supply as defined above.

In theory if the non-distribution constraint worked perfectly, its presence in the organization’s bylaws would be sufficient to guarantee the public interest embedded in the goods provided. Unfortunately this clause, as amply demonstrated by the literature on this topic, is not perfectly enforceable and can be evaded in many ways, by adopting indirect forms of profit redistributions like increase in compensation, overpricing of supply and other forms of self-dealing extensively illustrated in Herzlinger (1996). This fact suggested to investigate the other side of ownership, i.e. the right to residual control, basing the analysis on legal rules and common practices easily identifiable in the third sector.

So, starting from the main differences with the traditional ownership structure of the firm (where the “one share, one vote” rule typically applies and the entry of new shareholders is in any case subject to the existence of a limited number of shares), two common principles can be well identified in third sector organizations worldwide, especially among voluntary associations and social enterprises: the equality of individual voting rights and the absence of entry barriers for new members. A specific review of the Italian legal system (Balestri 2011a) reveals that these principles are quite common in public benefit organizations,Footnote 4 providing evidence that the above-mentioned rules are strictly connected to the public nature of the aims pursued. Also at the European level, a study conducted by Emes shows that the traits shared by social enterprises in the different European countries include a governance system that is not based on property rights in the form of shares and participation mechanisms involving all the parties concerned in the activities conducted (Defourny 2001), thus proving that such rules emerge spontaneously, regardless of the different national contexts. Generally speaking, such two basic principles of equality and inclusiveness, are the way public benefit (membership-based) organizations usually work all over the world.

This last aspect suggests that such rules or institutions emerge because they are better than any alternative, when there is some public interest to be guaranteed. Balestri (2011b) investigates how these alternative ownership structures influence the level of production of a specific kind of goods, characterized by the possibility of being sold in the market but also of generating positive public externalities. By building a simple utility maximization model, it analyses first the issue of individual optimal choice by the single entrepreneur in relation to the quantity of goods to be produced, and then it focuses on collective decisions adopted by the body of members. Lastly it examines the individual ex-ante choice of the type of firm to set up or to join for the production of such goods. The model leads to the conclusion that organizations whose ownership does not entail rights to returns and the right to control is “non-excludable” and “equally distributed” (i.e. without limits to admittance of new members and without differences in voting rights) can achieve efficientFootnote 5 results in terms of public goods provided. At the same time it demonstrates that such rules encourage the participation of the “ideological” individuals (Rose-Ackerman 1996) and discourage the pure-selfish ones, stimulating a sort of virtuous self-selection mechanism of members.Footnote 6

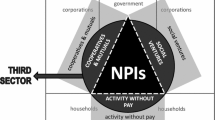

These results are due to the fact that both the rules examined, similarly to the non-distribution constraint that is supposed to work imperfectly, reduce the decisive voter’sFootnote 7 opportunity cost - in terms of private benefits - of enhancing the level of public good to be provided. More specifically, a positive relation is assumed between the individual share of residual control for each member (i.e. voting right) and each such member’s ability to extract personal private benefits, thus violating the non-distribution constraint through indirect forms of profit redistribution. So, equality in voting rights prevent the possibility for members more interested in voting for the maximization of profits to cast decisive votes for the adoption of resolutions by the body of members, while the non-excludable principle, which permits an increase in the number of members, dilutes the individual shares of earnings that can be diverted for private benefits. Generally speaking this configuration of property rights generates a structure of incentives that leads owners to enhance the level of public goods provided while traditional firms would produce such public goods at a sub-optimal level, due to positive externalities involved. This ideal type of public benefit organizations can be depicted as in Fig. 1.

This diagram describes a new and enlightening analogy between the ownership structure, especially in the right to residual control (i.e. without entry barriers to new members and without differences in voting rights), and the nature of public goods provided, whose benefits are distributed equally and non-exclusively. In particular, in the “one head, one vote” rule a sort of voluntary mechanism can be identified which leads, thanks to the type of preferences referred to in the previous section, to a spontaneous “Lindhal equilibrium”Footnote 8 since every member sets voluntarily the amount of the contribution paid for the production of a public good in the presence of equal voting rights and an equal availability of the public goods provided.

Such complementarities between the organization’s ownership structures and the nature of the goods provided, become more evident when the effects of each of the three rules examined on the nature of supply, are considered individually. So the results illustrated can be extended by relaxing one condition at a time. By removing the non-distribution constraint, for example, the ownership structure is quite similar to that of cooperatives where earning distribution is not totally forbidden but collective decision-making is normally based on the one head, one vote principle.Footnote 9 By relaxing the non-excludability rule, the organizations become more similar to mutual benefits organizations, which are better designed to provide the so-called “club goods”, as in the classical cases of tennis or golf clubs where the services are equally provided but are made available only to members. In fact, the efficient provision of such goods can be obtained only through an efficient mechanism of exclusion that prevents the group from exceeding its optimal size (Buchanan 1965). On the other hand, generally speaking, in public benefit organizations the widest possible participation is encouraged. The last case is reflected by the traditional ownership structure of corporations based on the “one share, one vote” rule, which represents the optimal solution for maximizing the flow of dividends and therefore the stock market value of a company (Grossman and Hart 1988).

There is clearly no doubt about the prevalence of corporations in the markets for private goods and services while they are residual or almost absent in the fields of economic activities traditionally addressed by nonprofit organizations, specifically where a public component of supply emerges. From this point of view, these evident patterns of specialization demonstrate strong complementarities between the organization’s ownership structure and the nature of supply, and are worth investigating further by extending the analysis to the whole institutional context, in which is what the next section will try to accomplish.

Toward an economic rationale for democracy

If one looks at the above-mentioned principles, clear and strong analogies can be seen with the basic rules of what we call “democracy”. By removing from the term democracy all adjectives that can be associated to it – e.g. direct democracy, representative democracy, liberal democracy or social democracy – there remain few and very essential elements to give a sort of “minimal definition” of democracy. According to Bobbio (1987), to this end it is worthwhile to define democracy in a simple procedural way, as a method to take collective decisions in accordance with at least two rules: allFootnote 10 participate in decision-making and a decision is adopted after a free discussion by the majority of participants. It is interesting to notice that Bobbio stresses that these rules are not necessarily connected to the political context but they can be applied to every kind of group (formal or informal), like associations, where decisions are taken according to the rules mentioned.

From this perspective, Dahl’s reconstruction (1998) to explain the nature of democracy is very enlightening. He starts from the simple acknowledgment that “all of us have goals that cannot attain by ourselves. Yet we might attain some of these by cooperating with others who share similar aims. Let us suppose, then, that in order to achieve certain common ends, you and several hundred other persons agree to form an association” (p. 35).

He imagines an initial discussion among members about the need to establish a constitution for the association, at the end of which everybody agrees that such constitution must comply with one elementary principle: that all members are to be treated as if they were equally qualified to participate in the process of making decisions about the policies that the association will pursue. In other words, in governing this association, all members are to be considered as “politically” equal.Footnote 11

Dahl (1998), in his classical work, identifies a minimum set of processes that must be continuously operating in a situation to qualify as democratic. So he stipulates five process-oriented fundamental criteria for democracy: voting equality, effective participation, enlightened understanding, control of the agenda and inclusion of all adult members in collective choices. These five criteria, especially the first four, make the democratic process fully consistent with the fundamental requisite of political equality, i.e. the condition whereby “the preferences of no one citizen are weighted more heavily than the preferences of any other citizen” (Dahl and Lindblom 1953, p. 41).

For the purposes of this paper, it is extremely interesting to notice that Dahl, in his analysis (1998), specifies that by “State” he means “a very special type of association that is distinguishable by the extent to which it can secure compliance with its rules, among all those over whom it claims jurisdiction, by its superior means of coercion” (p. 41): this is exactly the same perspective adopted in the paper.

However, passing from this normative perspective to a positive empirical approach, many other important elements may emerge as necessary for democracy to work effectively.Footnote 12 Nevertheless, in this theoretical context, it is important to underline that there is a minimum set of rules that qualify a democratic process of collective-decision making. This minimal set of rules, according to a common belief among scholars, is represented by the fact that each citizen/member is entitled to a single vote, equal in weight to that of all the others. Generally speaking, then, one can support the view that equality and inclusiveness (or non-excludability) are the key elements of the concept of democracy, whether they are applied to a group of friends, to the members of an association or to the citizenry as a whole.

So the ownership rules identified in the nonprofit sector emerge as minimal requisites of the democratic order. Moreover, as argued, both kinds of private and public institutional solutions, respectively nonprofit organizations and the State, seem to share the same nature in terms of the objectives pursued, the only difference being that the individual contribution to the provision of the public good in a nonprofit organization is voluntary while, in the second case, it is based upon the State’s power of coercion.

Actually, market failure in the production and allocation of public goods is considered, based on the normative approach of “Public Finance”, one of the main rationales for State intervention in the economy (Musgrave 1999). However, the normative approach of Public Finance is designed to identify efficient solutions without exploring the collective choice mechanisms that make it possible to attain these results, while in this case the interaction between the objectives pursued and the collective decision-making mechanisms adopted to achieve them, is analyzed.

Examining change in power systems, from anarchy to dictatorship and democracy, Olson (1993) concludes observing that “the moral appeal of democracy is now almost universally appreciated, but its economic advantages are scarcely understood” (p. 575). McGuire and Olson (1996) start from the assumption that rulers try to maximize taxes to pursue their objectives and that, unless they are “roving bandits”, they must take account of the production of resources and, consequently, the related incentives. In their analysis, democracy makes for a better trade-off between tax rates and overall output growth, as most voters have a greater “encompassing interest” in economic growth compared with an autocrat. For this reason, decision-making based on democratic procedures (i.e. majority rule) will lead to a higher provision of public goods, as these are regarded as means of production useful to achieve greater output growth, to the benefit of all.

This argument can be generalized by considering public goods not only as means of production but as factors of the utility function of individuals. In this sense models exist which examine the allocation of government budgets between public goods and private transfers. In a dictatorship, where political power is concentrated, a rational government leader will spend the public budget mainly on transfers targeted to politically influential groups and will spend less on non-exclusive public goods because much of their benefits would spill over to non-influential individuals. On the other hand, in a democracy, where control of government requires satisfying a large fraction of population, direct transfers are relatively unattractive while spending in public goods is strongly encouraged to obtain a sufficient level of consensus. This hypothesis has been tested by Deacon (2009), using cross-country data on public goods provision and empirical indicators of political regimes. Its findings show that dictatorial governments provide public schooling, roads, safe water, public sanitation and pollution control at levels far below democracies.

Interestingly, in the literature democracies have been compared mainly with dictatorships as historically these have been – in their different manifestations – the main foes of democracies. On the other side, it cannot be denied that, throughout history and especially since the end of WWII, democracy has been progressively expanding, to the point that it has become, at least in theory, the standard of reference for the exercise of public power.

If we leave aside all criteria of justice, as the historic emergence of dictatorships suggests, it is stimulating to see that the idea of a State organized according to principles usually applied by firms has never taken hold, even though the “one share one vote” rule is dominant among business organizations that compete in traditional markets. In fact, while this collective decision-making method has been overwhelmingly successful among firms that produce and sell private goods, it has never been used in government of the “res publica” and, specifically, in the production of public goods for which democratic institutions seem to have prevailed over other collective decision-making processes. Footnote 13

This interpretation is confirmed by the observation that, in the sphere of private autonomy, a special type of organization has emerged which is devoted to the production of public goods and services and has spontaneously adopted the principles of democracy for their own ownership structure. For these reasons, from an evolutionary perspective, such public benefit organizations resemble some sort of democratic nations at their early stage.

Particularly in countries where democracy has not yet been adopted and developed, such kinds of organization are paramount in coordinating collective actions oriented to common ends and, ultimately, in advancing democracy itself. It might be stated, turning Weisbrod’s theory on its head, that in these cases the spontaneous association of people who organize in accordance with the democratic method to pursue common goals, precedes and fosters the birth of democratic states.Footnote 14

Conclusions

While it is usual to talk about markets in terms of efficiency (or inefficiency), any reference to democracies calls to mind the idea of justice (or injustice) first. In other words, it is quite normal to judge markets in terms of efficiency as democracies in terms of justice. This paper, on the contrary, is an attempt to shed new light on the economic rationale of democracy, intended as a general method to take collective decisions by a group of individuals in order to achieve certain common ends which cannot be attained individually: as it has been argued this method basically involves a collective decision procedure, based on the rule that every individual can vote and that each individual vote has the same weight as that of everyone else. The main point of this article is that, as a mechanism for allocating limited resources, the democratic method is an efficient alternative for the provision of public goods, considering that it is a well-known fact that other allocative mechanisms, such as market-based ones, are not effective.

Nevertheless, shifting from our theoretical perspective to a practical one, many problems need to be addressed: specifically, it is necessary to understand how a minimum and purely procedural notion of democracy can be translated into a substantive democracy. Many such problems derive from the fact that when it comes to real choices, the rationality of individuals is limited by many factors, such as the incomplete information available to them and the individual effort necessary to process such information (Simon 1957). This fundamental aspect, of course, affects the perfect functioning of market as well the proper working of democracy.

If the sub-optimal provision of public goods is traditionally related to the free-riding problem, in the real institutional context, this problem is overcome mainly through the coercive power of the State and, as shown, through a system of voluntary contributions advanced by the nonprofit sector. Nevertheless these solutions do not solve completely the matter connected to the efficient provision of public goods, they simply shift it from a free riding problem to an agency problem as, like citizens who do not have complete information about public official doings, nonprofit members are not fully knowledgeable about the activities of the organization’s managers. In this context the opportunity cost in terms of private benefits that can be unlawfully obtained, becomes the most serious obstacle to the optimal provision of public goods. In this sense, nonprofit organizations seem to share failures similar to those of governments: actually, the violation of the non-distribution constraint can be considered equivalent to what we call, in the case of public officials, corruption.

Therefore, there is a tendency by restricted groups to keep secret certain areas of the decision-making process to receive illegal private benefits. Bobbio (1987) sees invisible power as a frequent and dangerous degeneration of democracy. In fact, generally speaking, the organizations that promote a public good do so publicly whereas those who seek benefits for a restricted group, at worst, do so secretly. At the opposite end of the spectrum, there are the different forms of deliberative democracy,Footnote 15 where all efforts are made to promote a full understanding of the issues at hand, “establishing conditions of free public reasoning among equals” (Cohen 1998, p. 186).

In essence, the main result of this theoretical work is the recognition of the concept of perfect democracy as an efficient allocative mechanism for public goods, in the same way as perfect market is traditionally considered for private goods. However, as argued, major and continuous efforts are necessary to make both work in the real world.

Notes

In this sense it is useful to consider Sen’s warning (1987) to separate the concept of rationality from that of self-interest maximization. He wrote “Why should it be uniquely rational to pursue one’s own self interest to the exclusion of everything else? It may not, of course, be at all absurd to claim that maximization of self interest is not irrational, at least not necessary so, but to argue that anything other than maximizing self interest must be irrational seems altogether extraordinary” (p. 15).

According to some writers, so-called “expressive value” can be used to justify voluntary contributions to public goods (Kanheman and Knetsch 1992). For instance, one may donate to an environmental association not only to contribute to environmental protection but also to express, in the eyes of others or in one’s own eyes, a personal sensitivity to environmental issues.

In particular, the survey covered the sector’s legislation, which is intended to identify, among nonprofit organizations provided for and regulated by the Italian civil code, entities that engage in socially worthy pursuits which are eligible to enjoy a number of benefits, ranging from tax breaks to the possibility to enter into agreements for the provision of general interest services: these include “voluntary organizations” (Law 266/1991), “social promotion associations” (Law 383/2000), “non-profit organizations of social utility” (Legislative Decree 460/1997) and “social cooperatives” (Law 381/1991”).

The model refers to an allocative kind of efficiency -between private and public goods- and does not address, for simplicity’s sake, the question of productive efficiency.

Valentinov (2007) shows how property rights structure in nonprofit organizations can affect intrinsically motivated stakeholders, leading to efficient results.

Defined as the voter pivotal, in the body of members, for a result prevailing over another in the simple case of a binary choice between the maximization of profit or the maximization of the level of public good provided (both subject to the constraint that revenues have to be enough to cover costs).

The Lindhal equilibrium requires each individual to face personalized prices such that everyone demands the same level of public goods and thus agrees on the amount that should be provided (Roberts 2008).

Typically, the products of cooperatives vary widely, ranging from higher social-content goods – as in the case of Italian social cooperatives – to more traditional mass consumption goods. Generally, however, their presence in the mass market is quite marginal compared with capitalist firms. Following an analysis based on voting mechanisms, Hart and Moore (1998) argue that cooperatives are preferable to corporations when interests are homogeneous while the opposite is true when interests are heterogeneous.

Bobbio notes that talking about “all” is an abstraction, considering that even in the democratic regime that comes closest to achieving perfection, individuals vote only after they have reached a certain age, consistent with the minimal competency requirements. Thus, he specifies that a “democratic regime” is “first and foremost a set of procedural rules for arriving at collective decisions in a way which accommodates and facilitates the fullest possible participation of interested parties” (Bobbio 1987, p. 19).

Many behavioral studies have examined the consequences of other kinds of equality, such as that of income, for the voluntary provision of public goods: one of the most recent works is that of Andersen et al. (2008). In general there is a negative correlation between propensity to cooperate and inequality among actors.

First of all, transparency and open access to full information about decision making processes. To be “fully” or at least “enough” informed requires a personal effort by each voter. In this sense, effective participation becomes a crucial point that can be facilitated by intermediate forms of association in civil society.

The preceding scheme can be used to describe also forms of government other than democracies: thus, relaxing the equal distribution of residual control a sort of “plutocracy” is obtained, the removal of non-excludability leads to forms of “oligopoly” while the absence of non-distribution constraint calls to mind the case of “dictatorship”. Obviously, it refers to theoretical patterns although, historically, there have been hybrid ideal-types combining such alternatives in different ways.

On the other hand, the growing influence of global corporations (based on “one share one vote” rule) on the public policies adopted by national governments, represents an increasing threat for the correct functioning of democracies worldwide.

The idea, largely due to Habermas’ work, that democracy revolves around the transformation rather than simply the aggregation of preferences (Elster 1998), suits better the case of deliberating about public rather than private goods or interests for which the concept of bargaining appear more adequate.

References

Andersen, L. R., Mellor, J. M., & Milyo, J. (2008). Inequality and public good provision: An experimental analysis. Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(3), 1010–1028.

Arrow, K. J. (1975). Gifts and exchanges. In E. Phelps (Ed.), Altruism, morality and economic theory (pp. 13–29). New York: Russell Sage.

Balestri, C. (2011a). Gli enti senza scopo di lucro nell’ordinamento italiano: un’ipotesi interpretativa fondata sulla natura della proprietà. Areté, 4(1), 81–100.

Balestri, C. (2011b). Property rights and the nature of nonprofit supply. Studi e Note di Economia, 16(2), 229–248.

Ben Ner, A., & Von Hoomissen, T. (1993). Nonprofit organizations in the mixed economy: a demand and supply analysis. In A. Ben-Ner & B. Gui (Eds.), The nonprofit sector in the mixed economy (pp. 27–58). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bobbio, N. (1987). The future of democracy. A defence of the rules of the game. New York: Polity Press.

Buchanan, J. M. (1965). An economic theory of clubs. Economica, 32, 1–14.

Carson, R. T., Flores, N. E., & Mitchell, R. C. (1999). The theory and measurement of passive-use value. In I. J. Bateman & K. G. Willis (Eds.), Valuing environmental preferences (pp. 97–130). New York: Oxford University Press.

Cohen, J. (1998). Democracy and liberty. In J. Elster (Ed.), Deliberative democracy (pp. 185–231). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dahl, R. A. (1998). On democracy. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Dahl, R. A., & Lindblom, C. E. (1953). Politics, economics and welfare. New York: Harper.

Deacon, R. T. (2009). Public good provision under dictatorship and democracy. Public Choice, 139(1–2), 241–262.

Defourny, J. (2001). From third sector to social enterprise. In C. Borzaga & J. Defourny (Eds.), The emergence of social enterprise (pp. 1–28). London: Routledge.

Elster, J. (1998). Introduction. In J. Elster (Ed.), Deliberative democracy (pp. 1–18). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Enjolras, B. (2009). A governance-structure approach to voluntary organizations. Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly, 38(5), 761–783.

Francois, P. (2003). Not-for-profit provision of public services. The Economic Journal, 113, C53–C61.

Grossman, S., & Hart, O. (1986). The costs and benefits of ownership: a theory of vertical and lateral integration. Journal of Political Economy, 94(4), 691–719.

Grossman, S., & Hart, O. (1988). One share-one vote and the market for corporate control. Journal of Financial Economics, 20(1), 175–202.

Gui, B. (1993). The economic rationale for the third sector. In A. Ben-Ner & B. Gui (Eds.), The nonprofit sector in the mixed economy (pp. 59–80). Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Hansmann, H. (1980). The role of nonprofit enterprise. Yale Law Journal, 89(5), 835–901.

Hart, O., & Moore, J. (1990). Property rights and the nature of the firm. Journal of Political Economy, 98(6), 1119–1158.

Hart, O., Moore, J. (1998) Cooperatives vs outside ownership. NBER working paper, n. w6421b.

Herzlinger, R. E. (1996). Can public trust in nonprofits and governments be restored? Harvard Business Review, 74(2), 97–107.

Kanheman, D., & Knetsch, J. L. (1992). Valuing public goods: the purchase of moral satisfaction. Journal of Environmental Economics and Management, 22(1), 57–70.

Krutilla, J. (1967). Conservation reconsidered. American Economic Review, 57(4), 777–786.

McGuire, M. C., & Olson, M. (1996). The economics of autocracy and majority rule: the invisible hand and the use of force. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 72–96.

Musgrave, R. (1987). Merit goods. In J. Eatwell, M. Milgate, & P. Newman (Eds.), The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics (pp. 452–453). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Musgrave, R. A. (1999). The nature of the fiscal state: the roots of my thinking. In J. M. Buchanan & R. A. Musgrave (Eds.), Public finance and public choice (pp. 29–50). Cambridge MA: The MIT Press.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press.

Olson, M. (1993). Dictatorship, democracy and development. American Political Science Review, 87(3), 567–576.

Roberts, J. (2008). Lindahl equilibrium. In S. N. Durlauf & L. E. Blume (Eds.), The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1986). Introduction. In S. Rose-Ackerman (Ed.), The economics of nonprofit institutions, studies in structures and policy. New York: Oxford University Press.

Rose-Ackerman, S. (1996). Altruism, nonprofits and economic theory. Journal of Economic Literature, 34, 701–728.

Salomon, L. M., & Anheier, H. K. (1992). In search of the non-profit sector. I: The question of definitions. Voluntas, 3(2), 125–151.

Samuelson, P. (1954). The pure theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 36(4), 387–389.

Samuelson, P. (1955). Diagrammatic exposition of a theory of public expenditure. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 37(4), 350–356.

Sen, A. (1987). On ethics and economics. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Simon, H. A. (1957). Models of man. New York: Wiley.

Sugden, R. (1984). Reciprocity: the supply of public goods through voluntary contribution. The Economic Journal, 94, 772–787.

Valentinov, V. (2007). The property rights approach to nonprofit organization: the role of intrinsic motivation. Public Organization Review, 7(1), 41–55.

Weisbrod, B. (1975). Toward a theory of the voluntary nonprofit sector in a three-sector economy. In E. Phelps (Ed.), Altruism, morality and economic theory (pp. 171–195). New York: Russell Sage.

Weisbrod, B. (1998). Modeling the nonprofit organization as a multiproduct firm. In B. Weisbrod (Ed.), To profit or not to profit: the commercial transformation of nonprofit sector (pp. 47–64). New York: Cambridge University Press.

Williamson, O. (1975). Markets and hierarchies. New York: Free Press.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License which permits any use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and the source are credited.

About this article

Cite this article

Balestri, C. The Other Side of Ownership in Nonprofit Organizations: an Economic Rationale for Democracy. Public Organiz Rev 14, 187–199 (2014). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-012-0214-7

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11115-012-0214-7