Abstract

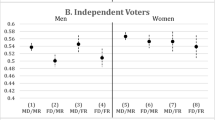

In this paper, we examine whether women candidates are more likely to spur turnout in election years when gender-related issues are central to the national debate. We argue that having women on the ballot in a gendered electoral environment mobilizes specific groups of voters. Utilizing voter files in Pennsylvania and Washington for 2014 and the more gender focused 2018 election, we evaluate this potential mobilizing effect in both primary and general midterm elections. Our results show that both female and male voters were more likely to turn out in the 2018 midterm elections when a woman was on the ballot for the U.S. House of Representatives. In Pennsylvania, which tracks registrants’ party affiliation, Democrats, members of third parties, and independents were particularly impacted by the presence of a female candidate. Moreover, in both states, a woman on the ballot was especially important for young people, a group that is traditionally less engaged. Utilizing a difference-in-difference approach, we confirm these results are not due to the endogenous selection of where women choose to run. These findings demonstrate that the mobilizing effect of women candidates is dependent on political context.

Similar content being viewed by others

Change history

20 January 2022

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-022-09772-8

Notes

For example, see FiveThirtyEight special on “When Women Run” (January 2020).

Additional details are available in Supplementary Appendix E.

Difference-in-difference was not performed for Pennsylvania because court ordered redistricting changed the district lines between 2014 and 2018.

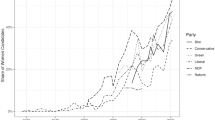

A total of 176 women were candidates for Congress in 2014, compared to 257 women in 2018 (CAWP, 2018c). The 2018 election resembles the 1992 election, dubbed the “Year of the Woman” for the surge in women candidates, particularly Democratic women, and focus on gender-related issues.

Millennials are those born between 1980 and 1996. Generation Z encompasses those born between 1997 and 2012. Only a small portion of Generation Z (those born 1997–2000) were eligible to vote in 2018.

A perspective also seen in the smaller group of adults that are part of Generation Z (Parker et al., 2019).

For an assessment of state polling accuracy see Guskin and Santamariña (2020). For additional details on differences between survey and voter file data as well as an analysis showing how survey data yields inaccurate estimates in this context, see online Appendix E.

The voter files contain key attributes of individual registrants including vote history, gender, age, and (for Pennsylvania) party registration.

Due to the maintenance of VFs as snapshots in time, we use separate VFs for the 2018 and 2014 models. 2018 models use a January 31, 2019 version of the Washington VF and a February 18, 2019 Pennsylvania VF. 2014 models use a December 2014 Washington VF and a February 6, 2017 export of the Pennsylvania VF. Ideally, we would have preferred a 2014 version of the Pennsylvania VF, unfortunately the state does not maintain old versions and the 2017 version was the oldest the authors had in their possession. Luckily, the 2017 version had voter history for the past 40 elections and district designations prior to the 2018 court ordered redistricting that altered district lines.

Data and replication codes for all analyses are available at the Political Behavior Dataverse page: https://dataverse.harvard.edu/dataset.xhtml?persistentId=doi:10.7910/DVN/GCZG82.

This is done by computing the predicted probability of voting when female candidate = 1 minus the probability of voting when female candidate = 0 with all constituent interaction terms set accordingly. See Brambor et al. (2006).

While we include every House primary, regardless of whether there is a female on the ballot, in the case of the 2014 Democratic primary, we exclude districts 15 and 18 because no candidates ran for their party’s nomination in those districts. In these excluded districts, no House candidate, male or female, would have impacted turnout.

References

Atkeson, L. R. (2003). Not all cues are created equal: The conditional impact of female candidates on political engagement. The Journal of Politics, 65(4), 1040–1061.

Atkeson, L. R., & Rapoport, R. B. (2003). The more things change the more they stay the same: Examining gender differences in political attitude expression, 1952–2000. Public Opinion Quarterly, 67(4), 495–521.

Bauer, N. (2020). The qualifications gap: Why women must be more qualified than men to win political office. Cambridge University Press.

Besley, T., & Case, A. (2000). Unnatural experiments? Estimating the incidence of endogenous policies. The Economic Journal, 110(467), 672–694.

Bobo, L., & Gilliam, F. D. (1990). Race, sociopolitical participation, and black empowerment. American Political Science Review, 84(2), 377–393.

Brambor, T., Clark, W. R., & Golder, M. (2006). Understanding interaction models: Improving empirical analyses. Political Analysis, 14(1), 63–82.

Broockman, D. E. (2014). Do female politicians empower women to vote or run for office? A regression discontinuity approach. Electoral Studies, 34, 190–204.

Brunner, J. (2018). Kim Schrier tries to make lack of political experience an asset in race with Dino Rossi. The Seattle Times, October 17. https://www.seattletimes.com/settle-news/politics/kim0schrier-tries-to-make-lack-of-political-experience-an-asset-in-race-with-dino-rossi/

Bryant, L. A., Hanmer, M. J., Safarpour, A. C., & McDonald, J. (2020). The power of the state: How postcards from the state increased registration and turnout in Pennsylvania. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09625-2

Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). (2018a). 2018: Women general election candidates for U.S. Congress and Statewide Elected Executive. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/2018-women-candidates-us-congress-and-statewide-elected-executive

Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). (2018b). 2018 summary of women candidates. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/potential-candidate-summary-2018

Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). (2018c). Women Candidates for Congress 1974–2018. https://cawp.rutgers.edu/sites/default/files/resources/canwincong_histsum.pdf

Center for American Women and Politics (CAWP). (2019). Women in Elective Office 2019. https://www.cawp.rutgers.edu/women-elective-office-2019

CIRCLE. (2018). Young People Dramatically Increase their Turnout to 31%, Shape 2018 Midterm Elections. November 7. https://civicyouth.org/young-people-dramatically-increase-their-turnout-31-percent-shape-2018-midterm-elections/

Crowder-Meyer, M., & Cooperman, R. (2018). Can’t buy them love: How party culture among donors contributes to the party gap in women’s representation. The Journal of Politics, 80(4), 1211–1224.

Cramer, R. (2018). In a 2018 democratic primary, it’s good to be a woman. Buzzfeed, May 6. https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/rubycramer/democratic-primary-women-candidates

Dolan, K. (1998). Voting for women in the ‘year of the woman.’ American Journal of Political Science, 42(1), 272–293.

Dolan, K. (2006). Symbolic mobilization? The impact of candidate sex in American elections. American Politics Research, 34(6), 687–704.

Enos, R. (2016). What the demolition of public housing teaches us about the impact of racial threat on political behavior. American Journal of Political Science, 60(1), 123–142.

File, T. (2014). Young-adult voting: An analysis of presidential elections, 1964–2012. Current Population Survey Reports, PS20-572. U.S. Census Bureau.

Fry, R. (2018). Millennials approach baby boomers as America’s largest generation in the electorate. Pew Research Center, April 3. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/03/millennials-approach-baby-boomers-as-largest-generation-in-u-s-electorate/

Fulton, S. A. (2012). Running backwards and in high heels: The gendered quality gap and incumbent electoral success. Political Research Quarterly, 65(2), 303–314.

Fulton, S. A., & Dhima, K. (2020). The gendered politics of congressional elections. Political Behavior, 42(1), 1–27.

Grossman, M., & Hopkins, D. A. (2016). Asymmetric politics: Ideological Republicans and group interest Democrats. Oxford University Press.

Guskin, E., & Santamariña, D. (2020). The 2020 polling paradox: Accurate results in some key states but big misses in others. The Washington Post, December 9. https://www.washingtonpost.com/politics/2020/12/09/2020-polling-paradox-accurate-results-some-key-states-big-misses-others/?arc404=true

Hainmeuller, J., & Hiscos, M. (2010). Attitudes toward highly skilled and low-skilled immigration: Results from a survey experiment. American Political Science Review, 104(1), 61–84.

Hanmer, M. J. (2009). Discount voting: Voter registration reforms and their effects. Cambridge University Press.

Hanmer, M. J., & Kalkan, K. O. (2013). Behind the curve: Clarifying the best approach to calculating predicted probabilities and marginal effects from Limited dependent variable models. American Journal of Political Science, 57(1), 263–277.

Hansen, S. B. (1997). Talking about politics: Gender and contextual effects on political proselytizing. The Journal of Politics, 59(1), 73–103.

Hemmer, N. (2017). #MeToo’s Roots in the feminist awakening of the 1960s. Vox, November 29. https://www.vox.com/the-big-idea/2017/11/29/16712454/me-too-feminism-sexual-harassment-twitter

Holman, M. R., Merolla, J. L., & Zechmeister, E. J. (2016). Terrorist threat, male stereotypes, and candidate evaluation. Political Research Quarterly, 69, 134–147.

Klein, E. (2018). The Ford–Kavanaugh sexual assault hearings, explained. Vox, September 28. https://www.vox.com/explainers/2018/9/27/17909782/brett-kavanaugh-christine-ford-supreme-court-senate-sexual-assault-testimony

Lawless, J. L. (2004). Politics of presence? Congresswomen and symbolic representation. Political Research Quarterly, 57(1), 81–99.

Mansbridge, J. (1980). Beyond adversary democracy. Basic Books.

Medenica, V. E., & Fowler, M. (2020). The intersectional effects of diverse elections on validated turnout in the 2018 midterm elections. Political Research Quarterly, 73(4), 988–1003.

Misra, J. (2019). Voter turnout rates among all voting age and major racial and ethnic groups were higher than in 2014. United States Census Bureau, April 23. https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2019/04/behind-2018-united-states-midterm-election-turnout.html

Newburger, E. (2018). Female candidates are calling out sexism more aggressively on the campaign trail. CNBC, September 27. https://www.cnbc.com/2018/09/27/female-candidates-are-more-aggressive-about-tackling-gender-based-attacks-in-2018-election.html

Newport, F. (2018). Top issues for voters: healthcare, economy, immigration. Gallup, November 2. https://news.gallup.com/poll/244367/top-issues-voters-healthcare-economy-immigration.aspx

Ondercin, H. L., & Fulton, S. A. (2019). Bargain shopping: How candidate sex lowers the cost of voting. Politics & Gender. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1743923X19000254

Palmer, B., & Simon, D. (2008). Breaking the political glass ceiling: Women and congressional elections (2nd ed.). Routledge.

Paolino, P. (1995). Group-salient issues and group representation: Support for women candidates in the 1992 senate elections. American Journal of Political Science, 39(2), 294–313.

Parker, K., Graf, N., & Igielnik, R. (2019). Generation Z looks a lot like Millennials on key social and political issues. Pew Research Center, February 12. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2019/01/17/generation-z-looks-a-lot-like-millennials-on-key-social-and-political-issues/

Pew Research Center. (2018). The generation gap in American politics. March 1. https://www.people-press.org/2018/03/01/the-generation-gap-in-american-politics/

Reingold, B., & Harrell, J. (2010). The impact of descriptive representation on women’s political engagement: Does party matter? Political Research Quarterly, 63(2), 280–294.

Rosenstone, S. J., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. Macmillan.

Rouse, S. M., & Ross, A. D. (2018). The politics of Millennials: Political beliefs and policy preferences of America’s most diverse generation. University of Michigan Press.

Safarpour, A. C., Gaynor, S. W., Rouse, S. M., & Swers, M. L. (2021). Replication data for: When Women Run, Voters Will Follow (Sometimes): Examining the Mobilizing Effect of Female Candidates in the 2014 and 2018 Midterm Elections. Harvard, Dataverse, V 1. https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/GCZG82.

Schneider, M. C., & Bos, A. L. (2014). Measuring stereotypes of female politicians. Political Psychology, 35, 245–266.

Thomsen, D. M. (2015). Why so few (Republican) women? Explaining the partisan imbalance of women in the US congress. Legislative Studies Quarterly, 40(2), 295–322.

Thomsen, D. M., & Swers, M. L. (2017). Which women can run? Gender, partisanship, and candidate donor networks. Political Research Quarterly, 70, 449–463.

Wattenberg, M. P. (2015). Is voting for young people? Routledge.

Wolak, J. (2019). Descriptive representation and the political engagement of women. Politics & Gender, 16(2), 1–24.

Wolak, J. (2020). Conflict avoidance and gender gaps in political engagement. Political Behavior. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-020-09614-5

Wolbrecht, C., & Campbell, D. E. (2017). Role models revisited: Youth, novelty, and the impact of female candidates. Politics, Groups, and Identities, 5(3), 418–434.

Zhou, L. (2018). 12 charts that explain the record-breaking year women have had in politics. Vox, November 6. https://www.vox.com/2018/11/6/18019234/women-record-breaking-midterms

Acknowledgements

We thank Michael Hanmer, Janelle Wong, Patrick Wohlfarth, Will Bishop, Tiago Ventura, Sebastian Vallejo Vera, and the participants at the University of Maryland American Politics Workshop for helpful feedback on earlier versions of this paper. We also thank Jennifer Wolak, Christina Wolbrecht, Melissa Deckman, and Daniel Smith for helpful conversations about this project. Thoughtful comments from Political Behavior editor Geoffrey Layman and the anonymous reviewers challenged us to improve the manuscript. Any errors or omissions remain our own.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Safarpour, A.C., Gaynor, S.W., Rouse, S.M. et al. When Women Run, Voters Will Follow (Sometimes): Examining the Mobilizing Effect of Female Candidates in the 2014 and 2018 Midterm Elections. Polit Behav 44, 365–388 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09767-x

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-021-09767-x