Abstract

This study rigorously compares the effectiveness of online mobilization appeals via two randomized field experiments conducted over the social microblogging service Twitter. In the process, we demonstrate a methodological innovation designed to capture social effects by exogenously inducing network behavior. In both experiments, we find that direct, private messages to followers of a nonprofit advocacy organization’s Twitter account are highly effective at increasing support for an online petition. Surprisingly, public tweets have no effect at all. We additionally randomize the private messages to prime subjects with either a “follower” or an “organizer” identity but find no evidence that this affects the likelihood of signing the petition. Finally, in the second experiment, followers of subjects induced to tweet a link to the petition are more likely to sign it—evidence of a campaign gone “viral.” In presenting these results, we contribute to a nascent body of experimental literature exploring political behavior in online social media.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Sharing private information with third parties is now an ingrained part of online behavior, with potential benefits for both traditional advocacy groups and networked movements.

The organization-centered design also addresses any concern about our lack of covariates for these traditional predictors of participation, although Sect. 8 analyzes differential effects by factors that we were able to capture, gender and organizational status.

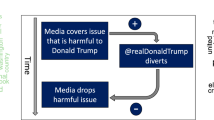

Contrast this with the case in which the organization is sending the public tweets—all of their followers are potentially exposed. When a random subset of users tweet the link, however, only a portion of the organization’s followers are exposed, allowing for experimental differences to be observed.

“Follower” condition: “You’re one of our most valuable followers! Please RT this petition to your friends to stop tax breaks to Big Oil (URL to petition)”; “organizer” petition: “You’re one of our most valuable organizers! Please RT this petition to your friends to stop tax breaks to Big Oil (URL to petition)”

Twitter’s API limits the number of DMs that an application can send to 250 per day. Subjects were randomly selected into batches.

This was done by using two different versions of the petition. See Fig. A1 in Online Appendix 4 for a screen shot of the encouragement, and Fig. A2 for the tweet window that popped up if a user clicked on the tweet encouragement.

By “scraping” we mean continually querying the Twitter API in order to capture tweets containing the URLs to either version of the petition. We used this approach because Twitter data is much easier to collect in real time than after the fact.

See Sect. 8 for the details of this procedure.

“Follower” condition: “You’re one of our most valuable followers! Help fight climate change by signing the petition & tweet to your friends! (URL)”; “organizer” condition: “You’re one of our most valuable organizers! Help fight climate change by signing the petition & tweet to your friends! (URL)”

Suppose that the true treatment effect is that a public tweet generates a single click per 10,000 followers exposed. With a sample size of 6687, we would expect to observe zero clicks about 51 % of the time.

These also seemed like plausible results ex ante; during a pilot study in which one of the authors sent automated direct messages to a subset of his followers, several recipients warned about “spam” or a possible virus.

See Online Appendix 1 for a full discussion of this assumption and its plausibility in this application.

We did not find any evidence of balance problems as in Study 1.

This could reflect the fact that the campaign was more timely and related to a current political dispute, in addition to the seasonality observed in other types of participation (Rosenstone and Hansen, 1993).

Online Appendix 2 presents randomization checks using these covariates.

References

Aaker, J., & Akutsu, S. (2009). Why do people give?. The role of identity in giving: Stanford University Graduate School of Business Research Paper.

Barr, D., & Drury, J. (2009). Activist identity as a motivational resource: Dynamics of (dis)empowerment at the G8 direct actions, Gleneagles, 2005. Social Movement Studies, 8(3), 243–260.

Benkler, Y. (2006). The wealth of networks: How social production transforms markets and freedom. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Bennett, W. L., & Segerberg, A. (2012). The logic of connective action: Digital media and the personalization of contentious politics. Information, Communication & Society, 15(5), 739–768.

Bimber, B., Flanagin, A. J., & Stohl, C. (2005). Reconceptualizing collective action in the contemporary media environment. Communication Theory, 15(4), 365–388.

Bowers, J., Fredrickson, M. M., & Panagopoulos, C. (2013). Reasoning about interference between units: A general framework. Political Analysis, 21(1), 97–124.

Bryan, CJ., Walton, GM., Rogers, T., Dweck, CS. (2011). Motivating voter turnout by invoking the sel. In Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (vol 108(31), pp. 12,653–12,656).

Converse, P. E. (1964). The nature of belief systems in mass publics. In D. E. Apter (Ed.), Ideology and Discontent. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Coppock, A. (2014). Information spillovers: Another look at experimental estimates of legislator responsiveness. Journal of Experimental Political Science, 1(02), 159–169.

Drury, J., Cocking, C., Beale, J., Hanson, C., & Rapley, F. (2005). The phenomenology of empowerment in collective action. British Journal of Social Psychology, 44(3), 309–328.

Farrell, H. (2012). The consequences of the internet for politics. Annual Review of Political Science, 15, 35–52.

Fowler, J. H., Heaney, M. T., Nickerson, D. W., Padgett, J. F., & Sinclair, B. (2011). Causality in political networks. American Politics Research, 39(2), 437–480.

Gaby, S., & Caren, N. (2012). Occupy online: How cute old men and malcolm X recruited 400,000 US users to OWS on Facebook. Social Movement Studies, 11, 367–374.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2000). The effects of personal canvassing, telephone calls, and direct mail on voter turnout: A field experiment. American Political Science Review, 94, 653–663.

Gerber, A. S., & Green, D. P. (2012). Field Experiments: Design, Analysis, and Interpretation. New York: W. W. Norton.

Gladwell, M. (2010). Small change: Why the revolution will not be tweeted. The New Yorker.

Gong, S., Zhang, J., Zhao, P., Jiang, X. (2014). Tweets and sales. Retrived from SSRN Working Paper.

Karpf, D. (2010). Online political mobilization from the advocacy group’s perspective: Looking beyond clicktivism. Policy & Internet, 2(4), 7–41.

Kobayashi, T., Ichifuji, Y. (2014). Tweets that matter: Evidence from a randomized field experiment in Japan. In Annual Meeting of the Southern Political Science Association.

Krueger, B. S. (2006). A comparison of conventional and internet political mobilization. American Politics Research, 34(6), 759–776.

Lupia, A., & Sin, G. (2003). Which public goods are endangered?: How evolving communication technologies affect the logic of collective action. Public Choice, 117(3–4), 315–331.

Marwick, A. E., & boyd, d. (2011). I tweet honestly, I tweet passionately: Twitter users, context collapse, and the imagined audience. New Media & Society, 13(1), 114–133.

McPherson, M., Smith-Lovin, L., & Cook, J. M. (2001). Birds of a feather: Homophily in social networks. Annual Review of Sociology, 27, 415–444.

Morozov, E. (2009). Iran: Downside to the ‘Twitter revolution’. Dissent.

Nickerson, D. W. (2007). The ineffectiveness of e-vites to democracy: Field experiments testing the role of e-mail on voter turnout. Social Science Computer Review, 25(4), 494–503.

Obar, J., Zube, P., & Lampe, C. (2012). Advocacy 2.0: An analysis of how advocacy groups in the United States perceive and use social media as tools for facilitating civic engagement and collective action. Journal of Information Policy, 2, 1–25.

Olson, M. (1965). The logic of collective action. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Porter, S. R., & Whitcomb, M. E. (2003). The impact of contact type on web survey response rates. Public Opinion Quarterly, 63, 579–588.

Rosenstone, S., & Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, Participation and Democracy in America. New York: MacMillan Publishing.

Shirky, C. (2008). Here Comes Everybody: The Power of Organizing Without Organizations. New York: Penguin Group.

Shulman, S. W. (2009). The case against mass e-mails: Perverse incentives and low quality public participation in US federal rulemaking. Policy & Internet, 1(1), 23–53.

Sinclair, B., McConnell, M., & Green, D. P. (2012). Detecting spillover effects: Design and analysis of multilevel experiments. American Journal of Political Science, 56(4), 1055–1069.

Taylor, S.J., Muchnik, L., Aral, S. (2014). Identity and opinion: A randomized experiment. Retrieved from SSRN.

Teresi, H., Michelson, M. (2014). Wired to mobilize: The effect of social networking messages on voter turnout. The Social Science Journal. doi:10.1016/j.soscij.2014.09.004.

Verba, S., Schlozman, K. L., & Brady, H. E. (1995). Voice and Equality: Civic Voluntarism in American Politics. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Verplanken, B., & Holland, R. W. (2002). Motivated decision making: Effects of activation and self-centrality of values on choices and behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82(3), 434.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the League of Conservation Voters, whose support and eagerness to include new experimental designs in its programs made this study possible. We also thank the Analyst Institute for its initial support of this project. The authors’ names are listed in alphabetical order. We particularly thank Amit Mistry, Vanessa Kritzer, Kristin Brown, and Mo Maraqa at LCV for their crucial roles in the planning and implementation of the two experiments. We are further grateful to Andy Przybylski and Neelanjan Sircar for extremely helpful discussions and feedback during the early stages of this project. We also thank Kevin Collins, Lindsay Dolan, Ben Farrer, Don Green, Lucas Leemann, three anonymous reviewers, and the editors of Political Behavior for their helpful comments and advice. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2014 Annual Meeting of the American Political Science Association in Washington, D.C., where we benefited from a lively discussion with participants and comments by Jaime Settle. This study would not have been possible without the use of Columbia University's Hotfoot High Performance Computing (HPC) Cluster for hosting the scraping programs.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Coppock, A., Guess, A. & Ternovski, J. When Treatments are Tweets: A Network Mobilization Experiment over Twitter. Polit Behav 38, 105–128 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9308-6

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-015-9308-6