Abstract

Under a ‘dirty hands’ model of undercover policing, it inevitably involves situations where whatever the state agent does is morally problematic. Christopher Nathan argues against this model. Nathan’s criticism of the model is predicated on the contention that it entails the view, which he considers objectionable, that morally wrongful acts are central to undercover policing. We address this criticism, and some other aspects of Nathan’s discussion of the ‘dirty hands’ model, specifically in relation to state entrapment to commit a crime. Using János Kis’s work on political morality, we explain three dilemmatic versions of the ‘dirty hands’ model. We show that, while two of these are inapplicable to state entrapment, the third has better prospects. We then pursue our main aim, which is to argue that, since the third model precludes Nathan’s criticism, a viable ‘dirty hands’ model of state entrapment remains an open possibility. Finally, we generalize this result, showing that the case of state entrapment is not special: the result holds good for policing practices more generally, including such routine practices as arrest, detention and restraint.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Dirty hands and undercover policing: Nathan’s criticisms

It is often said that politics is a dirty business. To be more precise: the ‘dirty hands’ model (DHM) of politics asserts that it inevitably involves situations where whatever the politician does is morally problematic. One might think that this analysis extends to the exercise of state power in general. Policing (or, more broadly, law enforcement) seems like an obvious example, particularly when it deploys coercive, violent, covert, or undercover methods or practices that arouse moral unease. The police use such methods arguably to pursue valuable ends, such as the prevention, detection and reduction of crime. Policing, in many instances, thereby creates situations where perhaps whatever police officers do will have morally problematic aspects. DHM might therefore be considered a fitting theoretical framework within which to analyse the morality of some central aspects of reactive and proactive policing.Footnote 1

Following Christopher Nathan (2017), we focus mainly upon a type of proactive policing that arouses moral unease and to which DHM might be considered applicable, namely undercover policing. Undercover policing, given its methods and special circumstances, is naturally prone to a ‘dirty hands’ (DH) analysis. For example, deception and manipulation are standard elements of the toolkit of undercover officers in their efforts to be accepted into the groups they aim to infiltrate. Commission of, or complicity in, crime can also be necessary to maintaining an undercover identity. This then easily leads to the kind of conflict situations in which DHM is particularly interested. Take the recent ‘spy cops’ scandal in the UK (Griffin, 2021). For over 40 years, more than 150 police officers (‘spy cops’) have infiltrated several political groups in the UK and elsewhere in Europe. In doing so, they have engaged in various harmful and morally problematic practices such as deceiving women into sex, fathering children while undercover, appearing in court under false identities, acting as agent provocateurs and participating in crime. Practices like the last three are of salient interest to DHM.

Nathan (2017: 37) introduces, but rejects as ‘unsatisfying’, the DHM of undercover policing:

The view often attributed to Machiavelli is that power inevitably involves doing some things that are wrongs, arising from genuine moral dilemmas. We must accept this moral residue, but we also do better not to dwell on our misdeeds. On this view, committing moral wrongs is part of the core of undercover work. The best we can do is to embrace the values we gain: in this case, the reduction of crime and the increase in security. It retains, nonetheless, a tragic element, since it is necessary that the work is performed, and those who perform it commit wrongs, thereby performing a sacrifice.[…]

A public that takes on board this view of manipulative policing will correctly feel that it puts wrongful acts at the centre of police practice. The wrongs may be justified by appeal to necessity, but unease will remain. Furthermore, one can reasonably expect that the effects of an internalisation of a dirty hands ethic by agents of a practice that is inherently secretive would be to encourage further secretiveness. A belief on the part of its agents that the practice is not wrongful is more conducive to public justification and regulation.Footnote 2

Nathan does not examine whether DHM applies to undercover policing in the first place.Footnote 3 Since his criticisms hold only if the model applies, it is pertinent to examine whether the model does indeed apply.

We do this by focusing on a specific method of proactive undercover law-enforcement, namely state entrapment to commit a crime (henceforth, ‘state entrapment’).Footnote 4 We have two main aims.

Our first main aim is to argue that, despite Nathan’s criticism, a viable DHM of state entrapment remains an open possibility. This main aim comes with two subsidiary aims. The first is to assess whether DHM applies to state entrapment. We show that there is a version of DHM that fits state entrapment. The second is to assess whether, when this account is applied to state entrapment, Nathan’s criticisms of DHM hold good. We argue that they do not.

We then proceed to our second main aim, which is to show that the case of state entrapment is not special: our results extend to policing practices more generally, including such routine practices as arrest, detention and restraint.

In Sect. 2, we provide a definition of state entrapment based on our previous work (in which we used the phrase ‘legal entrapment’ instead of ‘state entrapment’). In Sect. 3, we adapt to the case of state entrapment work by János Kis on political morality and DH. This enables us to set out three accounts that, fitting Nathan’s own depiction, understand the ethics of state entrapment in terms of a moral dilemma involving DH. We argue that the first two accounts, adapted from Kis, are inapplicable to state entrapment. The third, which is based on, but significantly different from, Kis’s formulation, has, we argue, better prospects of applying. It, however, leaves no room for wrongful acts, as opposed to acts that merely have bad aspects, as part of the picture: it therefore precludes Nathan’s fundamental criticism of DHM, namely his contention that on DHM a wrongful act is inevitable. In Sect. 4, we summarize our results up to that point. In Sect. 5, we consider a possible way of reinstating Nathan’s fundamental criticism so that it appeals to badness rather than wrongfulness. Our response to this attempt enables us to contest Nathan’s other criticisms of DHM and to extend to other policing practices our main result, namely that there is a version of DHM that both applies to state entrapment and resists Nathan’s criticisms. Section 5 is a concluding summary.

2 State entrapment to commit a crime: a definition

Entrapment is a prominent pro active (and normally undercover) policing method the morality and legality of which are highly controversial. This is evident from both primary legal sources and the secondary literature on entrapment in law and philosophy.Footnote 5 The entrapment methods used also showcase a possible connection to DHM. For example, in Jacobson v United States,Footnote 6 after some years spent ‘grooming’ their target (by holding themselves out as advocates of sexual freedom and freedom of choice), undercover police officers entrapped Jacobson by soliciting him to order child pornography via the mail. In Teixeira de Castro v Portugal,Footnote 7 plain-clothes police officers, after unsuccessfully trying to procure hashish from a drug user (and suspected small-time drug dealer), turned to his contact, Teixeira, whom they successfully convinced to procure heroin for them from a third source. Finally, in R v Syed,Footnote 8 officers posing on social media as ‘Abu Yusuf’ targeted Syed, who, as a result, engaged in what he believed was the purchase of weapons, a bomb, and target research for an attack in the UK. In such cases, we have police officers engaging in morally problematic acts (like setting traps, ‘grooming’, deceiving and manipulating). Entrapment scenarios, and similar morally problematic scenarios that can arise in undercover operations, naturally invite classification as instances of DH scenarios to which a DHM might apply.

To approach the connection between DHM and entrapment more strategically, let us formalize what we mean by ‘entrapment’ first. Cases of entrapment involve a party that intends to engage in entrapment, whom we call the ‘agent’ and a party that is entrapped, whom we call the ‘target’. Let the terms ‘party’, ‘agent’ and ‘target’ encompass both individuals and groups. We draw two distinctions, which cut across each other, concerning acts of entrapment. The first concerns the status of the agent; the second concerns the act that the target performs and that the agent procures.Footnote 9

State entrapment (also called ‘legal’Footnote 10 and ‘police’ entrapment) occurs when the agent is a law-enforcement officer, acting (lawfully or otherwise) in their official capacity as a law-enforcement officer, or when the agent is acting on behalf of a law-enforcement officer, as their deputy. When, on the other hand, neither of these is true of the agent, we have private entrapment (also called ‘non-state’ and ‘civil’ entrapment).

We distinguish between procured acts of criminal and of non-criminal types. An investigative journalist might entrap a politician into performing a morally compromising act that is not a crime in order that the journalist might expose the politician for having performed the act. When the act is non-criminal but is morally compromising (whether by being immoral, embarrassing, or socially frowned upon in some way), we are dealing with moral entrapment (using the word ‘moral’ in a wide sense). When the act is of a criminal type, we have criminal entrapment.

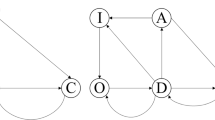

Accordingly, we classify acts of entrapment via the following two-dimensional matrix.

A | B | |

|---|---|---|

1. Is the agent acting (permissibly or otherwise) in their capacity as a law-enforcement agent or their deputy? | Yes | No |

2. Is the act that the agent intends the target to commit of a type that is criminal? | Yes | No |

We thus get four types of entrapment:

Type 1 = 1A + 2A = state entrapment to commit a crime

Type 2 = 1B + 2A = private entrapment to commit a crime

Type 3 = 1B + 2B = private moral entrapment

Type 4 = 1A + 2B = state moral entrapment

Type 1 entrapment, now called ‘state entrapment’ for short, is the kind that is relevant to our discussion. Elsewhere we argue that an act is one of state entrapment if and only if it meets the following five conditions:

-

(i)

a law-enforcement agent (or the agent’s deputy), acting in an official capacity as (or as a deputy of) a law-enforcement agent, plans that the target perform an act;

-

(ii)

the act is of a type that is criminal;

-

(iii)

the agent procures the act (using solicitation, persuasion, or incitement);

-

(iv)

the agent intends that the act should, in principle, be traceable to the target either by being detectable (by a party other than the target) or via testimony (including the target’s confession), that is, by evidence that would link the target to the act;

-

(v)

in procuring the act, the agent intends to be enabled, or intends that a third party be enabled, to prosecute (or to threaten to prosecute) the target for having performed the act.Footnote 11

3 Moral dilemmas, dirty hands and state entrapment

We now have a suitable notion of state entrapment at hand. The next step is to connect it to a suitable account of DHM. How are we to understand DHM? To begin, it is useful to recall the following main elements of Nathan’s description of DHM:Footnote 12

-

Moral wrongs (i.e., impermissible actions) are committed.

-

Genuine moral dilemmas are involved.

-

A moral residue is involved that we must accept.

-

The overall picture is tragic, despite a reduction in crime and an increase in security, because a moral wrong is unavoidable: a ‘sacrifice’ must be made to achieve these gains.Footnote 13

Let us clarify some important terms here. We take ‘moral dilemma’ to refer to a choice situation in which the agent is confronted with moral demands and whatever course is taken is morally problematic. We do not equate ‘morally problematic’ with ‘morally wrong’: this is so as not to foreclose the important possibility that, even if acting with DH involves facing moral dilemmas, these dilemmas are not best characterized in terms of moral wrongness. We explain the meaning of ‘moral residue’ below.

The core of Nathan’s depiction of DHM is that acting with DH involves a tragic moral dilemma in which moral wrongs are committed. That is, on a natural interpretation, DHM is presented as an offshoot of a tragic understanding of moral dilemmas. Following Kis (2008: Chapter 9), we explain three dilemmatic accounts of DHM.Footnote 14 We make some modifications, which we explain as we go along, to Kis’s discussion, and we somewhat simplify his presentation. Our modifications are substantial in the case of the third dilemmatic account of DHM. We consider how, if at all, each of these three dilemmatic accounts of DHM can be applied to the case of state entrapment. Unlike Kis and others in the literature on DH and/or moral dilemmas, we question an account only when this directly serves our primary purpose of examining the applicability or inapplicability of DHM to legal entrapment.

Of the three dilemmatic accounts, let us begin with the one that, we think, most closely matches Nathan’s depiction of DHM: the tragic account (TRAGIC). We begin each of the three subsections that follow with an indented summary of the account at issue.

3.1 The tragic account (TRAGIC)

The agent, S, is bound by two moral demands that cannot simultaneously be satisfied. Whichever demand S disregards, S violates a valid, in-force demand. The dilemmatic situation is inescapable, in that, even if S becomes involved innocently, S cannot come out of it innocently. However S acts, S will act impermissibly and incur guilt.

Recall that Nathan (2017: 37) says that situations involving DH acts retain a tragic element ‘since it is necessary that the work is performed, and those who perform it commit wrongs, thereby performing a sacrifice’. There are two necessity claims here.Footnote 15 The first claim is one of instrumental necessity. Nathan assumes that undercover policing methods, even if they are methods of last resort, are necessary means towards their ends. While it is doubtful that the actual deployment of undercover policing typically meets this condition (cf. Loftus, 2019), we assume, for the sake of argument, that the necessity towards such ends is a normative constraint on uses of undercover methods: that is, we assume that they are permissible only when they are instrumentally necessary towards their ends. The second form of necessity to which Nathan seems to allude is moral necessity: when the use of undercover methods is instrumentally necessary, the police have a moral duty to use them. This then leads to familiar slogans that aim to bring out the paradoxical nature of the resultant situation: that sometimes it is right to do what is wrong (de Wijze, 2007), or that sometimes whatever we do is wrong (Coady, 2008).

Slogans, however, do not help us to understand the underlying structure of the morality of the situation. We proceed in two steps. We first formalize the account, closely following Kis (2008: 238), in such a way that most clearly brings out the tragic element for which we are looking. Then, using the works of Stephen de Wijze, we consider a possible, and less radical, variation of TRAGIC. We proceed to argue that neither version of TRAGIC befits the morality of undercover policing or of state entrapment.

The relevant decision-making scenarios may be characterized as follows. Let S be the agent (in our case, the law-enforcement officer or their deputy), let a be a course of action that involves entrapment, and let b be an option that does not. To generate a dilemmatic situation, the following three background assumptions are needed:

A1: There is a moral demand that S should perform action a, and there is a moral demand that S should perform action b.

A2: S can satisfy each of the two demands separately.

A3: S cannot satisfy both demands together.Footnote 16

This gives us a situation of moral conflict, but not yet a situation of a moral dilemma. For that we require a further assumption:

A4TR: Of the two demands, neither overrides the other: both emerge undefeated.

A4TR is also crucial because it partially explains the tragic (and paradoxical) nature of the situation: there is no way that the agent can do the right thing without also doing something wrong. This, however, is only a partial explanation. According to Kis (2008: 239), moral dilemmas are tragic largely because of the agent’s lost innocence. The idea is that dilemmas are inescapable (in the sense that the choice situation occurs as a matter of necessity): one finds oneself in—in fact, one is put into—the dilemmatic situation through no fault of one’s own.Footnote 17 That is, one goes into the situation innocently, but, because of the nature of the choice involved, one cannot come out of it innocently.Footnote 18 Given the moral demand on each side of the dilemma, and that the dilemma is inescapable, TRAGIC has four tragic implications. To paraphrase Kis (2008: 239), these are:

I1TR: Whichever moral demand S chooses to disregard, S violates a valid, in-force moral demand.

I2TR: The dilemmatic situation is such that S may become involved in it innocently.

I3TR: Once in the dilemmatic situation, S has no opportunity to come out of it innocently.

I4TR: Whether S performs a or b, it will be appropriate for S to feel guilty.

On this account, moral dilemmas involve three layers of the tragic. The first is encapsulated in I1TR (and based on A4TR), and the second in the conjunction of I2TR and I3TR. Once these are in place, I4TR, the third layer, falls into place.

The question that concerns us, recall, is whether TRAGIC applies to the case of state entrapment. We think that the applicability of each of the three layers above can be called into question in the case of state entrapment. We focus on the first two. The third layer might not be supported by the phenomenology of these cases, if, that is, law-enforcement agents that entrap typically do not feel guilty about what they have done.Footnote 19 Of course, this does not rule out the view that it would be appropriate for them to feel guilty. Since the appropriateness of such reactive moral emotions is determined by the moral structure of the case, the third layer of the tragic is dependent upon the previous two layers.

With respect to the first layer, it is far from clear that A4TR (hence I1TR) holds true for most cases of state entrapment. Certainly, law-enforcement officers that entrap might be doing what is normally considered wrong pro tanto; after all, for example, they often tempt and deceive people, not always career criminals, into doing something criminal. Still, in the context of state entrapment, it is far from clear that A4TR holds true: given all the good that might be achieved through an act of entrapment (e.g., in terms of long-term crime prevention), it might be that the moral demand not to entrap is sometimes overridden. The literature on state entrapment contains conflicting views about its pro tanto moral permissibility,Footnote 20 and there is little discussion, if any, of how it fares in our overall moral assessment. In short, even on a charitable approach, there is reason to hold that A4TR is not generally true of scenarios of state entrapment. Rather than taking TRAGIC to apply across the board, it seems that it applies only to some, and not to all, cases.Footnote 21

With respect to the second layer, the inescapability requirement is of dubious applicability to cases of state entrapment. After all, state entrapment involves law-enforcement agents (or their deputies) choosing to entrap their targets. Although a law-enforcement agent might be ordered by a superior to entrap a target, the choice to entrap in this situation can hardly be construed as inescapable (whether for the superior or for the subordinate). In addition, both the superior and the subordinate, we can reasonably assume, made, or at least could have made, an informed choice when they became law-enforcement agents. It is hard to believe that those recruited into the police could not at least foresee, upon reflection, what might await them in the service. Police officers receive training that involves information on the different aspects of the job. This applies even more to those working undercover: they receive specialist training and are recruited from the ranks of ‘ordinary’ police officers. It might be that some agents stumble into being asked to engage in entrapment in jurisdictions in which entrapment is generally discouraged; still, this does not make their choice, in any relevant sense, inescapable.Footnote 22 It is reasonable to conclude, then, that the decision to engage in entrapment is, at least typically, a free and informed one. By contrast, the stereotypical case of an inescapable choice, which is often used in discussing TRAGIC, is Sophie’s choice (from Styron, 1979). Sophie had to choose which of her two children was to be sacrificed, and if she refused the choice both children were to be taken to the gas chamber. The choice, moreover, was imposed on her by Dr Mengele: Sophie did not create the choice situation, did not intend it, did not foresee it and did not have an innocent way out of it. Sophie, thus, truly loses her innocence, no matter what she does. It is doubtful, to say the least, that we can say anything remotely similar of law-enforcement officers that engage in entrapment.

Lastly, Nathan associates a moral residue with the DH situation. This is correct in one way and incorrect in another. If the agent has done wrong, then the agent, per I4TR, is guilty of wrongdoing, and this does not seem to us to constitute a moral remainder in a situation where all available alternatives are, by construction, morally wrong, being backed by undefeated moral demands. Perhaps, though, some might accept this, asserting that ‘moral residue’ here is referring to the moral phenomenology of these cases, i.e., to what the agent experiences, or, at least, to what it would be appropriate to experience. Nevertheless we do not consider it plausible to construe the moral residue as merely phenomenal. Instead, we think, the relevant residue should be located in the moral structure of entrapment and not (merely) in its phenomenology. More generally, we suggest, it is the moral structure of a scenario that determines what it is appropriate for a person in that scenario to feel.

It might be argued, however, that we have gone too far in our search for the tragic in DHM. A4TR is too exclusive, and it is thus easy ‘to beat’: there are few situations in ordinary life that conform to its demands, so it is not surprising that TRAGIC does not fit state entrapment. Could there be a version of TRAGIC that is more inclusive? Stephen de Wijze (2005, 2007, 2009, 2018 and 2024) has argued that TRAGIC is best understood as holding that in DH cases the agent’s choice is justified and overall right, but is also at the same time wrong: the justified choice, the choice that defeats all alternatives, is that of the lesser evil in the situation. On this approach, there is a tragic element, namely the choice of the lesser evil, that also serves as a moral remainder and accounts for the innocence lost.

We are doubtful, however, about whether de Wijze’s account would enhance the prospects of the application of TRAGIC to state entrapment.Footnote 23 Inescapability is still part of de Wijze’s account because, for him, it is a defining condition of DHM that the agent must dirty their hands owing to their becoming a causal part of the evil plans of others (de Wijze & Goodwin, 2009: 532; de Wijze, 2018: 132; cf. Nick, 2022). If we construe, as we have done so far, this inescapability as involving a form of necessity, i.e., as others’ evil plans necessitating the agent’s DH actions, then the condition is certainly not fulfilled in law enforcement (cf. Meisels, 2008: 166). On the other hand, if we interpret it as a form of duress, as de Wijze often does (e.g. 2007: 15, based on Stocker, 1990: 20), i.e., as others’ evil plans forcing the agents’ DH actions, even then, we think, it does not apply to state entrapment. Law-enforcement agents are not coerced into entrapping their targets by the criminal acts of their targets (or their broader milieu). They always have a way to ‘opt out’ in the ways we previously described.

Lastly, the question can also be raised about whether de Wijze’s account is incompatible with the two rivals to TRAGIC, namely RESIDUE and DIRTY that we discuss below. De Wijze’s version of TRAGIC bears similarities both to RESIDUE and to DIRTY and, we think, appears compatible with each of them. Here it is instructive to focus on de Wijze’s discussion about action-guidingness and disvalue, which is repeated in most of his articles and seems to be at the core of his account. To repeat, his view is that in DH cases, the DH act is overall morally justified, ‘even morally obligatory, yet nevertheless somehow wrong’ (de Wijze, 2005: 456, quoting Stocker, 1990: 10). How does this happen? His answer is as follows:

[I]n dirty hands scenarios such overall evaluations do not negate or render impotent the partial evaluations which were required to arrive at the overall evaluation. What is overridden is the action-guidingness of those ‘dirty features’, not its wrongness. ‘It (the act) remains as a disvalue which is still there to be noted and regretted.’ (de Wijze, 2005: 456 quoting, in the last sentence, Stocker, 1990: 10; as the passages are not totally identical occurs in de Wijze, 2007: 7; 2024: 205).

In short, what remains in DH cases is non-action-guiding moral wrongness, which is a disvalue.

It seems, then, that on de Wijze’s version of DHM, there is moral innocence lost, a moral violation has taken place, and the violation is best characterized in deontic terms. At the same time, however, in this passage, the deontic is curiously, we think, fused with the evaluative. Furthermore, we find the idea that the deontic status of a (putative) act is not action-guiding far from obvious. We can more easily accept that the action-guidingness remains in some form, or that the evaluative takes its place. Thus, from our point of view, de Wijze’s characterization of DHM is both compatible with, and possibly superseded by, each of RESIDUE (where there is an action-guiding remainder) and DIRTY (where there is non-action-guiding remainder, but not wrongness; there is badness instead). In short, it is not clear to us why de Wijze’s version of TRAGIC could not be reinterpreted as a version of RESIDUE (switching from wrongness to residual obligations to compensate), or, especially, of DIRTY (switching from wrongness to moral badness). From what we can see in his writings, de Wijze gives no reason that would count against making this change while, as we see things, the ‘controversy’ surrounding some of his core ingredients—moral wrongness as disvalue and moral wrongness as not action-guiding—puts the burden of proof squarely on his side.Footnote 24

Given this, and the fact that neither version of TRAGIC—neither our initial characterization following Kis nor de Wijze’s—provides clear applicability to entrapment, we have good reason to continue our inquiry and to consider other conceptualizations of DHM.

3.2 The moral residue account (RESIDUE)

S is bound by two moral demands, to perform a and to perform b, that cannot simultaneously be satisfied. The demand to perform a overrides the demand to perform b, but b’s normative force does not evaporate: rather, it gives rise to a derivative requirement that the target of S’s act must receive redress.

Williams (1965) has argued that what happens in moral dilemmas is that, contrary to A4TR, one moral demand overrides the others, but without the overridden demands’ being silenced: they ‘stick around’; their force does not evaporate.Footnote 25 In particular, these defeated demands generate derivative demands to compensate for, or to repair, the damage done: this is the moral residue that gives RESIDUE its name. As Kis (2008: 251) puts it:

The defeated ought has no action-guiding force in the immediate context of the situation in which the choice is being made, but it has action-guiding force in the context of a later choice that emerges in virtue of S’s action.

That is, the decision situation is more complex than in TRAGIC. If agent S opts to perform action b, then S must perform action ca (where this represents compensating for, or repairing the harm caused by, having failed to perform action a). If, on the other hand, S opts to perform a, then S must then perform cb (where this represents compensating for, or repairing the harm caused by, having failed to perform b). The decision is more complex because, when deciding how to act, S must not only decide whether to do a or b, but also which, if either, of ca and cb is a feasible option.

Before we address the question of application, let us this time highlight an important general problem: it appears that RESIDUE’s claim to a moral residue vanishes on closer analysis (Kis, 2008: 252). After all, if S makes the right choice by choosing to act on the overriding demand and also compensates the victims of this choice (for the failure to take the other courses of action that were initially open), then no moral residue remains. S simply did the right thing, on both levels (acting and then compensating): the moral universe remains intact, and S comes out of the situation (morally) innocent.

While there is a way around this problem, the way round suggests that the proper form of RESIDUE, the application of which to state entrapment we intend to query, is not the one with which we began. The way round is as follows. As Kis (2008: 253) points out, if there is irreparable damage involved in a choice situation, then a moral residue would necessarily remain. (Kis calls this ‘non-eliminable moral residue’.) This appears to restore the tragic character of S’s choice-situation, since there would be no way for S fully to satisfy the requirements that apply. To formalize it, the following account of the ‘moral residue’ account would hold. Let us start with the original account of moral conflict:

A1: There is a moral demand that S should perform action a, and there is a moral demand that S should perform action b.

A2: S can satisfy each of the two demands separately.

A3: S cannot satisfy both demands together.

We require, to follow this version of RESIDUE, a fourth assumption (Kis, 2008: 253):

A4MR: Performing action a involves a non-eliminable moral residue, and either performing b involves a non-eliminable moral residue or the demand to perform it is not overriding.

Replacing A4TR with A4MR produces its own problems, however. First, as Kis (2008: 253) points out, if damage is irreparable, i.e., if it cannot be repaired, then, if ‘ought’ implies ‘can’, it is not the case that it ought to be repaired.Footnote 26 This means that the ‘rediscovered’ tragic element in RESIDUE becomes diluted. If, on the one hand, the damage is reparable, then no residue need remain. If, on the other hand, the damage is irreparable, then a residue remains but redress is not required (because it is impossible). In either case, no derivative moral requirement remains that could, if violated, trigger a tragic dénouement.Footnote 27

Secondly, Kis (2008: 253) argues that this does not rule out the possibility that it would be appropriate for S to feel bad about having failed to compensate the victim(s) of S’s act. This feeling should not be guilt and perhaps not even regret or remorse. Still, S can think of the act as morally problematic and feel bad about this. This gives a thinly tragic analysis: whatever S does, it is appropriate for S to feel bad about the chosen act. It is doubtful, however, exactly what Kis has in mind here: what would ‘feeling bad’ amount to, and why would it be appropriate? Moreover, as far as the moral analysis of entrapment is concerned, this leaves us with very little of the tragic aspect of the situation as Nathan originally described it.

Furthermore, while the original version of RESIDUE was generally applicable to state entrapment, the present version applies only to those instances of it that involve irreparable damage. Arguably, however, most cases of state entrapment are too mundane to involve irreparable damage: law enforcement does not normally involve killing or maiming entrapped subjects, for example, or harming other parties.Footnote 28 In fact, this gets worse if we consider that, on A4MR, the choice not to entrap either should not be overriding (which is not obvious) or should cause irreparable damage (which is not generally the case). In short, what we gain in ‘tragedy’ by focussing on irreparable damage, we lose in scope of application.

Lastly, there is good reason to think that RESIDUE fails to preserve the dilemmatic nature of DH. As Kis (2008: 255–256) shows, reference to irreparable damage cannot be what constitutes moral dilemmas, because hard choices of the form depicted by A1–A3 that are not moral dilemmas can also involve irreparable damage. For example, a rescuer might allow someone to die by deciding to save another, and the choice might be perfectly well supported by moral reasons. RESIDUE fails to distinguish such cases from genuine moral dilemmas.

RESIDUE, we conclude, is not a viable dilemmatic account of DHM suitable for application to the case of state entrapment. Let us turn, then, to the third account drawn from Kis’s discussion.

3.3 The ‘dirty hands’ account (DIRTY)

S is bound by two moral demands, to perform a and to perform b, that cannot simultaneously be satisfied. Although the demand to perform a overrides the demand to perform b, performing a remains morally bad. Hence, while it is right for S to choose to perform a, what S does remains morally bad.

The above summarizes our version of this account, which differs significantly from Kis’s. We now explain Kis’s version, and then, using it as background, explain and justify the details of our version. We start with the usual three assumptions to depict moral conflict:

A1: There is a moral demand that S should perform action a, and there is a moral demand that S should perform action b.

A2: S can satisfy each of the two demands separately.

A3: S cannot satisfy both demands together.

The fourth assumption, as before, is the one that fulfils the task of accounting for the dilemmatic nature of the situation (Kis, 2008: 264). Moral reprehensibility is, on Kis’s account, the central concept that features in this assumption (Kis, 2008: 267):

A4DH: Performing action a is morally reprehensible, and performing action b is either morally reprehensible or the demand to perform it is not overriding.

Kis (2008: 260–263) explains how A4DH is meant to help secure a dilemmatic account of DHM. This involves five central ideas. The first concerns the aforementioned notion of moral reprehensibility. Kis holds that an act can be right, hence morally acceptable, in certain circumstances, and nonetheless morally reprehensible in the same circumstances. This is possible, says Kis, introducing his second central idea, because some acts, such as murder and betrayal, have essential properties that make them morally reprehensible irrespective of the circumstances.Footnote 29 Some concepts, like murder or betrayal, Kis says, have descriptive content that cannot be separated from evaluative criteria: the acts they describe cannot be identified in morally neutral terms. Murder and betrayal, Kis asserts, remain morally reprehensible even if in the given situation they are, all things considered, the morally right thing to do.

The third idea is that threshold deontology (TD) is an appropriate approach to normative ethics (cf. Nagel, 1986; Coady, 2018: §7; Alexander & Moore, 2021: §4). At bottom, the idea is that we can evaluate an act in two ways: according to the states of affairs it produces (the viewpoint typically associated with consequentialism) and according to how it treats its object (the viewpoint typically associated with deontology). It is the latter that is crucial: if an act fails to treat its object as it should be treated then this makes it morally reprehensible. Now, action-based constraints, on this view, often outweigh concerns related to consequences: the putatively good consequences that the action would bring about are outweighed by the constraints relating to how the action would treat its object. Nevertheless, beyond a certain threshold (e.g. avoidance of great harm) considerations of the consequences override those that relate to the intrinsic nature of the action. Importantly, even in such cases, the concerns pertaining to the nature of the action remain in place as evaluative considerations: it is morally right to avoid great harm, but what is, with respect to the nature of the action, inappropriate treatment, nevertheless remains inappropriate treatment.Footnote 30 Hence the act, albeit morally right because justified by its consequences, remains morally reprehensible: this is a moral residue. Kis’s fourth central idea is that this makes DIRTY paradoxical: whatever the agent does will be morally acceptable and unacceptable at the same time.

Finally, we come to Kis’s fifth idea: if we consider the acts the reprehensibility of whose natures is overridden by the goodness of their consequences in dilemmatic situations then we see that, although they are morally acceptable (because right) and unacceptable (because reprehensible) at the same time, they are not blameless and blameworthy at the same time. The justified nature of the act means that no blame is appropriate. The act is morally reprehensible, but the proper response to this is not blame, but regret or remorse. An observer’s proper responses are not resentment and indignation, but fear and pity. Kis (2008: 265) depicts the appropriate phenomenology of DH acts as lying between cases of faultless involuntary contributions to accidents (where only what Williams (1976) calls ‘agent-regret’ is appropriate) and blameworthy wrongdoing (where guilt and blame are appropriate).

While Kis’s formulation of DIRTY would, we think, apply to state entrapment, our interest is in a version of DIRTY that expunges some commitments from Kis’s formulation. Getting rid of these commitments has, we think, two main virtues: first, it renders the amended account more plausible; secondly, it expands the number, and the variety, of morally interesting situations to which DIRTY can be applied.Footnote 31

We amend Kis’s first commitment so that the notion of reprehensibility is replaced with the idea that an act can have a morally bad aspect. Thus, on our version of DIRTY, an act can be right, hence morally acceptable, in certain circumstances, but nonetheless have a morally bad aspect that, in the same circumstances, does not evaporate. Our next move is to specify further the nature of such aspects. Here, too, we disagree with Kis, now concerning his second central idea: essential properties. Besides holding that serious critical questions can be asked about Kis’s understanding of essentialism,Footnote 32 we also reckon that if a viewpoint in normative ethics can forswear a metaphysical commitment, while still doing its normative-ethical work, then it is better for it to do so. In any case, we think that it is not the idea of an act’s having essential properties that is, at bottom, relevant to deontology. Instead, it is the familiar idea that, apart from having extrinsic consequences (which they bring about), some acts have in themselves, as tokens of their types, morally relevant intrinsic features (such as being a promise, the breaking of a promise, or a lie). An appropriate example might be if a field surgeon, to a patient’s great extrinsic benefit, in order to prevent a tragic outcome for the patient, and under orders, violated the patient’s autonomy by administering a treatment to which the patient had expressly not consented. This act would have, we think, overwhelming extrinsically good consequences (in that, so to speak, it would save life or limb), while it would also be intrinsically morally bad (in that it would violate the patient’s autonomy).

It is this notion of intrinsic moral badness that we propose to use instead of Kis’s notion of essential moral reprehensibility. We are now in a position to replace Kis’s A4DH with our own proposal:

A4DH*: Performing action a has a morally bad aspect, and performing action b either has a morally bad aspect or the demand to perform it is not overriding.

We next deploy this notion within Kis’s third idea: TD.Footnote 33 The example above of the field surgeon is a case at hand: given the overwhelming positive consequences (even when balancing them against the negative consequence of pain), the threshold is reached, and administering the treatment becomes the morally right thing to do, despite the fact that doing so is intrinsically morally bad because it violates the patient’s autonomy (since the soldier has not consented to the treatment).

Furthermore, given A4DH*, we diverge from Kis’s view that an act can be both morally acceptable (because right) and morally unacceptable (because reprehensible) at the same time.Footnote 34 We supplant Kis’s notion of moral reprehensibility, and his subsequent paradoxical deployment of the notion of moral unacceptability, with the notion that, in the dilemmatic situation, a TD account sees one course of action as right but intrinsically bad. In the situations to which our amended version of DIRTY is meant to apply, the following happens. When the agent acts rightly, intrinsic moral badness is nevertheless produced. When the agent acts wrongly, an intrinsic moral good is promoted, but a more significant extrinsic ill is brought about. In short, on DIRTY, while the agent can choose to act rightly, they cannot avoid doing something morally bad at the same time. This leftover intrinsic moral badness is a moral residue that is left behind when the agent acts rightly.

Finally, to turn to Kis’s fifth central idea, from a phenomenological point of view, how should the agent then regard their action? Here we think that Kis’s phenomenological picture can be weakened somewhat. We agree that in DIRTY it can be appropriate for the agent to feel remorse at having to take the course of action in question, even though taking that course is permissible (and perhaps even mandatory) in the circumstances, and that this remorse is something more than mere agent-regret (Williams, 1976), though less than guilt. (Perhaps it is tragic-remorse: see de Wijze, 2005.) On our account, however, remorse would be appropriate only in situations in which the agent’s chosen course involved a grave moral ill. Similarly, observers in such serious cases can react with fear and pity, as Kis proposes. In other, less serious, situations, perhaps moral disappointment would be appropriate (cf. Menges, 2020).Footnote 35

For our modified version of DIRTY to apply to state entrapment, the act of entrapment must be intrinsically morally bad in the sense explained above. One candidate for such badness is suggested by the contention in Howard (2016: 25) that entrapment (whether state or private):

subverts the moral capacities of entrapped persons. To subvert an agent’s moral capacities is to interfere with the agent’s practical reasoning in ways that increase the likelihood she will culpably choose to act wrongly. Such activity […] is incompatible with respect for that agent. Specifically, it is incompatible with […] an attitude of support for the successful operation of others’ moral capacities.

While we are inclined to think that there are other morally bad aspects of state entrapment, some of which may be agent-centred rather than target-centred,Footnote 36 we agree with Howard that such subversion is involved in state entrapment, and that it is morally undesirable.Footnote 37 While Howard sees the subversion that is involved as sufficient to make entrapment wrong, rather than just bad, within the version of DIRTY that we are entertaining it is seen merely as a bad aspect. When is this badness outweighed, rendering state entrapment permissible? As in Kis’s discussion, this occurs when great harm is at stake. Now, there are many mundane cases where the target of state entrapment is unlikely to have otherwise proceeded to cause great harm; state entrapment is unlikely to be justified in such cases. On the other hand, the level of subversion inherent in a particular act of state entrapment might also be relevant: if this is minor, then entrapment may be morally justified even for minor benefits.Footnote 38

While the extent of DIRTY’s applicability as justification for real-life cases of state entrapment is thus unclear, this does not restrict its theoretical applicability: only those cases of entrapment are permissible where the intrinsic moral badness of the action is outweighed by the (overall) goodness of the consequences. Even in these cases, the account is non-consequentialist. This is because it remains the case that the action of state entrapment has intrinsic negative moral value that the gains do not nullify. DIRTY not only explains why state entrapment is sometimes permissible, but also why it is aptly regarded (e.g., in regulating policing operations) as a method of last resort. State entrapment is still bad, and the fitting response to having done it is, under at least some circumstances, remorse.

No doubt, many theoretical questions can be asked about DIRTY, but, as before, we have tried to stay clear of the general debate concerning moral dilemmas and DH. Our interest has been primarily in the application of DIRTY to state entrapment. Unlike TRAGIC and RESIDUE, DIRTY appears to be a good candidate for this. It has no place for the idea that whatever the agent in a DH scenario does will be morally wrong. It is therefore immune to Nathan’s fundamental criticism of DHM. At the same time, it retains not only the dilemmatic nature of the choice situation, but some element of the tragic (when the intrinsic moral badness qualifies as a grave moral ill) and a moral remainder as well.

4 Summary

Our substantive discussion took as its starting point Nathan’s criticisms of the DHM of undercover policing (Nathan, 2017: 37). Nathan made four assertions about what would happen if the DHM of undercover policing were to be publicly endorsed, which we now enumerate:

(1) The public would correctly feel that morally wrongful acts were at the centre of police practice.

(2) Despite the justification of these acts, public unease would remain.

(3) The police would become, because of internalization of this ethic, even more secretive.

(4) By contrast, if there were a better model for understanding the morality of undercover policing that would yield the belief on the part of its practitioners (the police) that it were not wrongful, that would be more conducive to public justification.

(2) and (3) are social-scientific predictions. (1) is too, but it incorporates a theoretical assertion that we have been subjecting to philosophical scrutiny: namely, that DHM takes wrongful acts to be at the centre of police practice. This is Nathan’s fundamental criticism of DHM.

We have highlighted Nathan’s characterization of DHM (specifically, of undercover policing) as morally dilemmatic, tragic and involving a moral residue. We have examined whether there was a way to flesh out Nathan’s remarks into a fully-fledged account that was applicable, in particular, to state entrapment. In doing so, we have deployed three accounts of the DHM of politics that we have adapted from Kis (2008). We have argued that the first two, TRAGIC and RESIDUE, are inapplicable to the case of state entrapment. We have proposed a modified version of the third account, DIRTY, and we have argued that it is applicable to state entrapment. Crucially, however, DIRTY, whether in Kis’s original form or in our modified version, rejects the idea that whatever the agent in a DH scenario does will be morally wrong (albeit, perhaps, also at the same time right). Nathan’s case against the DHM of undercover policing was predicated upon the contention that, on DHM, undercover policing involved moral wrongdoing. Of the three accounts here surveyed, then, DIRTY remains a good choice in the face of Nathan’s criticism.

5 Policing, dirty hands and public justification

At this point, a possible rejoinder is that Nathan’s fundamental criticism can be revised by replacing the appeal to moral wrongness (from his characterization of DHM) with an appeal (from our version of DIRTY) to what is intrinsically morally bad. Accordingly, DHM would be characterized via the following list (with changes italicized):

-

Acts with morally bad aspects are committed.

-

Genuine moral dilemmas are involved.

-

A moral residue is involved that we must accept.

-

The overall picture is tragic, despite a reduction in crime and an increase in security, since a moral evil is unavoidable: a ‘sacrifice’ must be made to achieve these gains.

The amended criticism could then be summarized as follows (only (1) and (4) change):

(1*) The public would correctly feel that acts with morally bad aspects were at the centre of police practice.

(2) Despite the justification of these acts, public unease would remain.

(3) The police would become, because of the internalization of this ethic, even more secretive.

(4*) By contrast, if there were a better model for understanding the morality of undercover policing that would yield the belief on the part of its practitioners (the police) that it did not involve acts with morally bad aspects, that would be more conducive to public justification.

We think, however, that neither (1*) nor (4*) is a serious problem, and, partly for the reasons that support this suggestion, that neither (2) nor (3) grounds a serious objection.

Let us start with (1*). The first thing to notice here is that DHM, under our modified version of DIRTY, applies, at least in principle, not only to the comparatively exotic, and certainly specialized, domains of undercover or covert proactive policing, but also to any forceful or coercive elements of policing that are necessary to the practice of law-enforcement. Among the many such forceful and coercive elements of policing, consider such routine reactive practices as arrest, detention and restraint. Although they may be for the greater good of their targets, and/or of society, these practices, given their forceful or coercive natures, can justifiably be resorted to only when the probability is relatively low that their ends can effectively and efficiently be achieved by non-forceful and non-coercive means. This is because when an act is forceful or coercive, that is an intrinsically morally bad aspect of it.

Consequently, unlike in the case of the original version of Nathan’s criticism, which was predicated on the idea that morally wrong acts were central to DHM, the contention that acts with morally bad aspects are at the centre of police practice is neither specific to the case of undercover policing nor, we suggest, particularly contentious. Indeed, the observation that even everyday police practice involves morally bad aspects is innocuous, realistic, and compatible with conscientious, but morally careful, policing. To deny it would seem naïve. Moreover, the contention that policing involves acts with morally bad aspects is not something that is distinctive of DHM: it arguably follows from any realistic picture of the ethics of everyday policing. In short, our modified version of DIRTY provides an account of DHM that applies not only to state entrapment, but to every method or practice of policing, whether undercover or not, that involves intrinsically bad aspects. These considerations suggest that (1*) is true but innocuous: it is ineffectual as a criticism of the DHM of undercover policing.

Turn now to (4*). The relationship between DH acts and public justification has two sides. On the one hand, there is the side, emphasized by Nathan, of the agent and the institution of which they are a part. The agent gets DH; thereby, so does their institution. The resulting demand for public justification puts a heavy burden on the agent’s institution (in this case, the police). Now, if wrongful acts are crucial to undercover policing, then of course this makes public justification of it difficult. Nathan is right about this. On our version of DIRTY, however, the relevant acts are not morally wrong, but ‘only’ morally bad. This makes public justification easier, and perhaps much easier, than Nathan envisages. In fact, given the above-noted wide scope and generality of DIRTY, it is difficult to see what one could propose as a realistic and non-naïve contrasting alternative.

It is, however, the other side of the relationship that is even more important for the evaluation of (4*): the side of the public to whom justification is owed. If policing did not centrally involve acts with morally bad aspects, then it would not, as against more typical forms of labour, be in special need of moral and political (as against economic) public justification. That is, in an important sense, (4*) gets things backwards, and Nathan’s objection can be inverted. He emphasizes the consequences of embracing the DH ethic for public morale, as well as for police morale. The very ethic he targets, however, has resourcesFootnote 39 in it to control these detrimental effects, and these resources centre exactly on the notion that Nathan finds detrimentally affected: public justification.That is, exactly because the acts involved are DH, public accountability is placed centre stage in DHM.

It is not difficult to understand why this is so. If an agent commits a morally bad—let alone morally wrong—act, then the agent owes, at a minimum, an explanation-cum-justification to the targets (or victims) of their act. Now, from this it does not automatically follow that this must take a public form.Footnote 40 Still, there are good reasons to think that it should do so (cf. Kis, 2008: Chapter 8). First, there is the problem of moral corruption. On the one hand, in policing we need—if we go along with the idea that there are morally justified DH acts—people that are willing to dirty their hands. On the other hand, we do not want these people to dirty their hands too easily. Lord Acton’s apothegm ‘power tends to corrupt, and absolute power corrupts absolutely’ (Acton, 1907: 504) is as true in policing as it is elsewhere. This is further underlined by a second reason: uncertainty. No police officer can be sure that when they entrap, for example, their reasons are indeed good. Hence, just as with moral corruption, we do not want to make it too easy for police officers to act on their reasons, however good they take them to be. The two considerations also connect: those that are more easily inclined to dirty their hands are also more likely not to care that they might be acting wrongfully. In short, public justification, for good reasons, is an essential part of DHM, and not an external constraint or demand on it.Footnote 41

Two further conclusions concern how the modified version of DIRTY undermines (2) and (3). In relation to (2), to the extent that the public is at ease with the idea that policing is necessary at all, the public will be, or at least ought rationally to be, at ease with the idea that the police will engage in forceful or coercive acts: for policing is, as the term suggests, an inherently forceful and coercive endeavour. It suggests this whether it is taken broadly (to include, for example, the activities of the intelligence services) or more narrowly (to exclude, for example, educational and outreach work undertaken by the police). Contrary to (3), the modified DIRTY account makes increased secrecy by the police less likely than would a contrary account that denied that morally bad acts were an inevitable aspect of policing. For, given that such acts are inevitable aspects of policing, and that the acknowledgement of this is crucial to the need for public (moral and political) justification of the activities of police forces, the rational and strategically appropriate attitude to those acts, on the part of the police, is to admit their presence and to justify them. Secrecy, on the contrary, would be both irrational and counter-productive in respect of public justification.

6 Conclusion

We have focused on DHM as a possible framework for analysing the morality of undercover policing, specifically in relation to state entrapment. We took as our starting point the criticisms of the model by Nathan (2017). We had two main aims. Our primary aim was to see if DHM applied to state entrapment, and to establish whether, if it applied, Nathan’s criticisms of it held. Our secondary aim was to see if state entrapment were a special case or our analyses could be extended to policing practices generally. To achieve these aims, we presented three possible versions of DHM, loosely taking our inspiration from Nathan’s remarks and making extensive use of Kis (2008). We found that the first two accounts, TRAGIC and RESIDUE, were inapplicable to the case of state entrapment. We argued that the third, DIRTY, applied, but left no room for morally wrong acts. When Nathan’s criticism was amended, we found that DIRTY was immune to all four of Nathan’s criticisms, and, in fact, that DIRTY could be made to apply to many standard instances of police work. In short, once we consider the range of resources available to DHM, Nathan’s critique is either precluded or loses its force, not just in the case of state entrapment, but also beyond.

6.1 Cases Referred to

England and Wales

R v Syed (Haroon) [2018] EWCA Crim 2809, [2019] 1 WLR 2459, [2019] Crim LR 442.

European Court of Human Rights

Teixeira de Castro v Portugal [1998] ECHR 52, (1999) 28 EHRR 101, App No. 25829/94 (9 June 1998).

United States (Federal)

Jacobson v United States 503 US 540 (1992).

Data availability

Not applicable.

Materials and/or code availability

Not applicable.

Notes

Klockars (1980) introduces the so-called ‘Dirty Harry’ case, derived from the famous film of that name, to illustrate the kind of situation that is of interest to DHM as a model of policing. Klockars (1980: 37–38) suggests that the problems that arise in these situations also arise in ‘familiar police practices’ such as ‘street stops and searches and victim and witness interrogation’. Others agree, often relating DHM, albeit not necessarily correctly, to so-called ‘noble cause’ corruption: see Alexandra (2000) and Cooper (2012). For a dissenting voice, see Miller (2016).

In his subsequent book, Nathan (2022: 30–32) qualifies his position: he reduces but does not eliminate the DH element of undercover policing, holding that a good deal of, but not all, undercover police work is not dilemmatic, either because of liability or because of consent. We do not claim that all undercover policing is apt for construal in terms of the DHM. Our concerns are with specific scenarios and practices.

DHM is merely the starting point for his discussion, as a model we should avoid. We take Nathan’s objections only to urge us to look for a better moral account of undercover policing, if there is any. We do not read him as offering a refutation of DHM per se.

Undercover policing is often seen as a crucial policing method, and it is becoming increasingly ‘normalized’ (HMIC 2014; cf. Loftus 2019). While the morality of entrapment is often discussed from other angles, it is interesting to consider the viability of applying DHM to it. Although we do not think that entrapment is by definition an undercover method, its uses are predominantly in undercover operations. The attempt to apply DHM to entrapment is therefore a natural development from Nathan’s depiction of how DHM might apply to undercover policing in general.

See further Hill, McLeod & Tanyi (2024).

Jacobson v United States 503 US 540 (1992).

Teixeira de Castro v Portugal [1998] ECHR 52, (1999) 28 EHRR 101, App No. 25829/94 (9 June 1998).

R v Syed (Haroon) [2018] EWCA Crim 2809, [2019] 1 WLR 2459, [2019] Crim LR 442.

Our notion of procurement is technical: the agent has an intentional influence, via directly related communicative acts, on the target’s will. See Hill, McLeod & Tanyi (2018) for further discussion.

Hill, McLeod & Tanyi (2018); entrapment (without the qualifier) differs in that conditions (i), (ii), and (v) are more inclusive.

Nathan lists an aspect of DHM that we do not list: that we, and undercover agents themselves, are encouraged not to dwell too much on their misdeeds. This seems to us a peculiar addition, however: it might have been true of Machiavelli’s original formulation of DHM, but it is not widely accepted today. We return to this issue, albeit indirectly, at the end of our paper.

The sacrifice consists in acting contrary to a value: in other words, it constitutes a kind of moral damage.

There are other ways of conceptualizing DHM and we will discuss them where needed. The focus on Kis’s discussion as our framework, however, serves our dialectical purposes well given that our main aim is the modest one of showing that a viable DHM can apply to undercover policing despite Nathan’s critique.

We think, in fact, that there is, or, rather, there has to be, also a third one, which we introduce later using the term ‘inescapability’. We discuss this crucial aspect of TRAGIC there and then but not yet here.

Under the influence of Railton’s (1996) discussion (and perhaps that of Stocker, 1990), Kis (2008: 238) characterizes moral dilemmas as involving conflicting cases of ‘ought’. We have instead characterized dilemmas in terms of conflicting moral demands: we take this to be closer to the spirit of Railton’s discussion, and a better way of attaining generality. While this choice can be disputed, we do not think it changes anything of substance in the paper.

There are voices in the literature that advise against appealing to necessity in this context: see Shklar (1984: 167) and McDonald (2000: 188–189). They merely warn us, however, that one can always use ‘necessity’ in a self-serving way, as an excuse for anything. The response to this, as we outline at the end of the paper, is to put emphasis on public justification and accountability.

One could decouple lost innocence from the nature of the choice situation. This is what Tillyris (2015, 2016, 2019) does in his dynamic DHM. For him, politicians make a series of choices and, certainly after the first choice, there is no lost innocence: the politician dirties their hands willingly, does not suffer and may even feel good about it. While Tillyris might be right about politics, his DHM does not fit TRAGIC; nor does it fit, we think, the cases of state entrapment or undercover policing.

Even if they do feel bad about what they did, there can be other explanations of this fact. They might doubt that they have done the right thing (cf. Nielsen, 2000). Other explanations of bad feelings (regret and remorse) are possible, and we appeal to them in what follows.

See Hill, McLeod & Tanyi (2024).

One could say that certain forms of policing need to be done—a social choice—so someone must dirty their hands. While this may be true in politics, it is far from clear that we need entrapment or undercover policing in general. Besides, there is something morally problematic about making an individual choice inescapable on the basis of a (presumed) social choice.

The coherence of the account can be questioned, but this is true of our original version of TRAGIC as well. See de Wijze (2024) for a defence. What is more concerning, from a purely theoretical point of view, is that, despite de Wijze’s suggestion (2007: 15) that tragic dilemmas such as Sophie’s can fit into his scheme, it is unclear to us how they could fit into it. This is because, unlike in Sophie’s case, the DH act is right, on his view, because it defeats the other alternatives in the situation.

Goodwin (2009) uses a distinction between ‘wrong’ and ‘wrongful’ (‘right’ and ‘rightful’) to accommodate the concerns that drive our questioning here. Goodwin does not consider this as a merely linguistic intervention (147–150). We do not have space to discuss his intriguing proposal, but it is not clear to us that his accommodation is better than what RESIDUE or DIRTY can offer.

RESIDUE is supported naturally by a picture of competing pro tanto reasons, the balancing of which gives us an all-things-considered ‘ought’-judgement. See Alexandra (2000), who depicts ordinary cases of ‘noble cause’ corruption in exactly this way.

Admittedly, it is controversial that ‘ought’ implies ‘can’ (OIC). In fact, this has relevance elsewhere in the debate on conceptualizing DHM, since the incoherence argument against TRAGIC uses OIC.

Could there be a way to escape between the horns of our dilemma? Perhaps the reason why we need to compensate victims of wrongdoing, even if the damage is irreparable, is communicative, so we should compensate as much as we can. The same conclusion could be arrived at by using Goodin’s (1989) distinction between compensation1 and compensation2. It is not clear that on either proposal the dilemma is escaped, however. For now, the question is whether the compensation on offer is of the right (moral) kind such that the damage done does not remain, in the relevant moral sense, irreparable. If it does not so remain, then the question is why this would not amount to full compensation, thus eliminating the tragic aspect of RESIDUE.

A reviewer pointed out to us that Goodin (1989) might contain the resources in it significantly to broaden the circle of relevant irreparable damages. This might indeed be so, but we are not yet convinced that it is so when applied to entrapment, given what Goodin (1989: 65, 73) says about ‘irreparable losses’.

This idea is based on his reading of Marcus (1996).

It is not taken up in Kis’s presentation exactly how TD sees the inter relation of reasons grounded in the consequences and reasons grounded in the intrinsic nature of the action. The notion of exclusionary reasons in Raz (1999) seems to be in the background here, although it is notoriously hard to interpret (Adams, 2021).

Kis (2017: 290–292) discards TD in favour of a distinction borrowed from Scanlon (2008: Chapter. 1) between the ‘critical question’ (regarding the agent’s attitudes) and the ‘deliberative question’ (regarding the agent’s acts). In this way Kis hopes to avoid the paradoxical nature of his earlier position. Our formulation of DIRTY retains TD, however, while avoiding both inconsistency and the idea of moral reprehensibility.

A venerable approach to metaphysics regards substances as things of the right kind to have essences; acts would not count, according to this tradition, as things of the right kind. Furthermore, it is clear that Kis is working with a modal account of essence, according to which all and only those properties that an entity has ‘in all possible worlds’, or as a matter of necessity, are of its essence. That conception of essence has often been contested, especially since Fine (1994).

We admit that there are problems with TD. De Wijze (2024) holds that on TD there is no moral remainder and that it collapses into consequentialism. We do not want to defend TD in this paper, however, so (2) is relevant only if any alternative to TD is unproblematic. The standard alternative in the DH literature, as in Nick (2022), is value pluralism, and that too is a deeply disputed view. Moreover, as we explain later in the paper, our version of TD is decidedly non-consequentialist. As for (1), we in fact use TD to make sense of a moral remainder (as moral badness). To make a general remark, TD does not seem to us to be more decisively or convincingly defeated than are, or are said to be, all the other major ethical theories.

This paradox, or seeming paradox, might be thought to be an undesirable feature of Kis’s account. This perhaps raises bigger questions, which we do not propose to address, about the appropriate philosophical methodology to use when approaching a seeming paradox.

If there is no guilt and blame, is punishment in order? The standard answer, starting with Walzer (1973) and most recently defended in de Wijze (2013), is affirmative. Roadevin (2019) argues against punishment, preferring instead what she calls ‘no-fault forgiveness’. Meisels (2008) puts forward another proposal, in which there is an ‘acoustic separation’ between what is communicated to the public (punishment) and what is ‘whispered’ to the courts (find a legal excuse such as suspension or pardon). Each of these positions, however, depends on the inescapability aspect discussed in TRAGIC, which aspect DIRTY lacks. Besides, as we argue at the end of the paper, public justification and accountability are important aspects of our view, and these would be toothless without at least the looming threat of punishment, it seems to us.

It is crucial for Howard that the target ‘will culpably choose to act wrongly’. Like some courts elsewhere (see Hill, McLeod & Tanyi, 2024), Howard is therefore implicitly rejecting the specific entrapment doctrine that has become orthodox under US Federal law. We also reject that doctrine. Moreover, in saying that entrapment subverts the target’s moral capacities short of nullifying culpability, Howard would be able to avail himself of the distinction (explained in Hill, McLeod & Tanyi, 2018) between causing the target to commit an act (e.g. by the administration of a mind-altering drug) and procuring the act (as we there understand it).

This connects to the discussion between those that advocate for a fixed threshold and those that argue for a sliding-scale form of TD. See Alexander & Moore (2021: §4).

Liberal democracy with a strong independent media is a good example of such a resource. In the case of the police, further institutional measures include all the ways of overseeing police work, the extensive discretionary rights of police officers, their original authority coming directly from the law, and other procedural barriers on police work.

Public justification has not always been the norm. The prince of Machiavelli (1988) has no inner life, for example. The politician of Weber (1994) suffers internally only. Although the ‘Catholic’ model of Walzer (1973) proposes social expression, this is primarily for the repentance of sins in order to achieve salvation.

We agree with McDonald (2000) that clean hands as tied hands are better than dirty hands. Tillyris (2015, 2016), following Bellamy (2010), argues that politicians should not reveal their dirt to the public. What holds for a career politician, however, might not hold for a law-enforcement officer. Besides, it is possible that, if Tillyris is right, we have a sort of tug of war on our hands: we should hold the politician to account, but perhaps the politician should then try to avoid and deceive us in response. Overall, we prefer a model of policing, but also of politics, that tries to minimize DH instances: a middle way between the democratic ‘dirty hands’ model (de Wijze, 2018; Nick, 2019), on which DH acts are either impossible or practically unrealistic, and the Tillyris–Bellamy model, on which DH acts are not only excusable but also hidden from view.

References

Acton, J., (1907). Historical essays and studies. Edited by J.N. Figgis & R.V. Laurence. Macmillan.

Adams, N. P. (2021). In defence of exclusionary reasons. Philosophical Studies, 178(1), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-020-01429-8

Alexander, L., & Moore, M. (2021). Deontological ethics. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2021 edition). https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/win2021/entries/ethics-deontological/

Alexandra, A. (2000). Dirty Harry and dirty hands. In T. Coady, S. James, S. Miller, & M. O’Keefe (Eds.), Violence and police culture (pp. 235–248). Melbourne University Press.

Bellamy, R. (2010). Dirty hands and clean gloves: Liberal ideals and real politics. European Journal of Political Theory, 9(4), 412–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474885110374002

Carlon, A. (2007). Entrapment, punishment, and the sadistic state. Virginia Law Review, 93, 1081–1134. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25050372.

Coady, C. A. J. (2018). The problem of dirty hands. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.), Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy Fall 2018 edition, ed. E.N. Zalta, https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/dirty-hands/

Coady, C. A. J. (2008). Messy morality: The challenge of politics. Oxford University Press.

Cooper, J. A. (2012). Noble cause corruption as the consequence of role conflict in the police organisation. Policing and Society, 22(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/10439463.2011.605132

de Wijze, S. (2005). Tragic-remorse—The anguish of dirty hands. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 7(5), 453–471. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-005-6836-x

de Wijze, S. (2007). Dirty hands: Doing wrong to do right. In I. Primoratz (Ed.), Politics and morality (pp. 3–20). Palgrave Macmillan.

de Wijze, S. (2018). The problem of democratic dirty hands: Citizen complicity, responsibility, and guilt. The Monist, 101(2), 129–149. https://doi.org/10.1093/monist/onx039

de Wijze, S. (2013). Punishing ‘Dirty Hands' - Three Justifications. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 16(4), 879–897.

de Wijze, S. (2024). Are dirty hands possible? Journal of Ethics, 28(1), 187–214. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-022-09411-8

de Wijze, S., & Goodwin, T. L. (2009). Bellamy on dirty hands and lesser evils: A response. British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 11(3), 529–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-856X.2009.00371.x

Dillof, A. M. (2004). Unravelling unlawful entrapment. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology, 94(4), 827–896. https://doi.org/10.2307/3491412

Fine, K. (1994). Essence and modality. Philosophical Perspectives, 8, 1–16. https://doi.org/10.2307/2214160

Goodin, R. E. (1989). Theories of compensation. Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 9(1), 56–75. https://doi.org/10.1093/ojls/9.1.56

Goodwin, T. (2009). The problem of dirty hands: Defending a special case of inescapable moral wrongdoing. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Manchester.

Griffin, N. S. (2021). ‘Everyone was questioning everything’: Understanding the derailing impact of undercover policing on the lives of UK environmentalists. Social Movement Studies, 20(4), 459–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/14742837.2020.1770073

Hill, D. J., McLeod, S. K., & Tanyi, A. (2018). The concept of entrapment. Criminal Law and Philosophy, 12(4), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-017-9436-7

Hill, D. J., McLeod, S. K., & Tanyi, A. (2021). Entrapment and ‘paedophile hunters’. Public Ethics Blog, 25 August 2021. https://www.publicethics.org/post/entrapment-and-paedophile-hunters

Hill, D. J., McLeod, S. K., & Tanyi, A. (2022a). What is the incoherence objection to legal entrapment? Journal of Ethics and Social Philosophy, 21(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.26556/jesp.v22i1.1181

Hill, D. J., McLeod, S. K., & Tanyi, A. (2022b). Entrapment, temptation and virtue testing. Philosophical Studies, 179(8), 2429–2447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11098-021-01772-4

Hill, D.J., McLeod, S.K., & Tanyi, A. (2024). Entrapment. P. Caeiro, S. Gless, & V. Mitsilegas, with M.J. Costa, J. de Snaijer, & G. Theodorakakou (Eds.), Elgar Encyclopedia of Crime and Criminal Justice. Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781789902990.entrapment

HMIC. (2014). An Inspection of undercover policing in England and Wales Retrieved June 6, 2020, from. http://www.justiceinspectorates.gov.uk/hmicfrs/wp-content/uploads/an-inspection-of-undercover-policing-in-england-and-wales.pdf

Howard, J. W. (2016). Moral subversion and structural entrapment. Journal of Political Philosophy, 24(1), 24–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopp.12060

Hughes, P. M. (2004). What is wrong with entrapment? Southern Journal of Philosophy, 42(1), 45–60. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6962.2004.tb00989.x

Kis, J. (2008). Politics as a moral problem. CEU Press.

Kis, J. (2017). A politika mint erkölcsi probléma. Kalligram.

Klockars, C. K. (1980). The Dirty Harry problem. ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 452(1), 33–47. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271628045200104

Loftus, B. (2019). Normalizing covert surveillance: The subterranean world of policing. British Journal of Sociology, 70(5), 2070–2091. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-4446.12651

Machiavelli, N. (1988). The Prince. Edited by Q. Skinner & R. Price. Cambridge University Press.

Marcus, R. B. (1996). More about moral dilemmas. In H. E. Mason (Ed.), Moral dilemmas and moral theory (pp. 23–36). Oxford University Press.

McDonald, M. (2000). Hands: Clean and tied or dirty and bloody? In P. Rynard & D. P. Shugarman (Eds.), Cruelty and deception: The controversy over dirty hands in politics (pp. 187–197). Broadview Press.

Meisels, T. (2008). Torture and the problem of dirty hands. Canadian Journal of Law and Jurisprudence, 21(1), 149–173. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0841820900004367

Menges, L. (2020). Blame it on disappointment. Public Affairs Quarterly, 34(2), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.2307/26921125

Miller, S. (2016). Noble cause corruption in policing. In S. Miller, Corruption and anti-corruption in policing: Philosophical and ethical issues (pp. 39–51). Springer Nature. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46991-1_3

Nagel, T. (1986). The view from nowhere. Oxford University Press.