Abstract

Background

Only 5–10% of all adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are reported. Mechanisms to support patient and public reporting offer numerous advantages to health care systems including increasing reporting rate. Theory-informed insights into the factors implicated in patient and public underreporting are likely to offer valuable opportunity for the development of effective reporting-interventions and optimization of existing systems.

Aim

To collate, summarize and synthesize the reported behavioral determinants using the theoretical domains framework (TDF), that influence patient and public reporting of ADRs.

Method

Cochrane, CINAHL, Web of science, EMBASE and PubMed were systematically searched on October 25th, 2021. Studies assessing the factors influencing public or patients reporting of ADRs were included. Full-text screening, data extraction and quality appraisal were performed independently by two authors. Extracted factors were mapped to TDF.

Results

26 studies were included conducted in 14 countries across five continents. Knowledge, social/professional role and identity, beliefs about consequences, and environmental context and resources, appeared to be the most significant TDF domains that influenced patient and public behaviors regarding ADR reporting.

Conclusion

Studies included in this review were deemed of low risk of bias and allowed for identification of key behavioural determinants, which may be mapped to evidence-based behavioral change strategies that facilitate intervention development to enhance rates of ADR reporting. Aligning strategies should focus on education, training and further involvement from regulatory bodies and government support to establish mechanisms, which facilitate feedback and follow-ups on submitted reports.

Similar content being viewed by others

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Impact statements

-

Further focus on relevant theory is advocated to develop effective interventions to enhance the low rates of patient and public reporting of ADRs, and support medication safety.

-

Patient and public reporting of adverse drug reactions are reported to be linked to their knowledge; their belief of the consequences of reporting; perceptions of their role in medications safety; and environmental context factors including the influence of healthcare professionals and the ease of reporting.

-

Strategies to enhance patient and public ADR reporting should focus on education, training and further involvement from regulatory bodies and government support to establish mechanisms, which facilitate feedback and follow-ups on submitted reports.

Introduction

Patient and public reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) offers numerous advantages to health care systems, namely promotion of patient rights, earlier detection of important ADRs, and benefits to healthcare organizations from patient involvement [1, 2]. Similarly, there is growing evidence of their value in establishing stronger causality of ADRs [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Initially established to address substantial under-reporting rates of healthcare professionals, in recent years, systems to receive ADR reports from patients and public have become increasingly common globally [3, 5, 7]. The World Health Organization (WHO) Programme for International Drug Monitoring facilitates the exchange of information, policies, guidelines, and other normative activities between countries and support countries in their pharmacovigilance activities, including patient and public reporting [8]. However, there remains substantial under-reporting of ADRs by both healthcare professionals; and patients and public. It is estimated that only 5–10% of all ADRs are reported [9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18]. Under-reporting delays the triggering of signals and subsequently making decisions to maintain an appropriate drug benefit-to-harm balance [1].

Multiple articles, including recent investigations, have presented the factors contributing to healthcare professionals’ underreporting [10, 16, 19,20,21,22,23,24]. The findings have indicated that the knowledge and attitudes of healthcare professionals appear to be a significant influence; as well as a lack of time, different care priorities, uncertainty about the drug causing the ADR, difficulty in accessing reporting forms, lack of awareness of the requirements for reporting, and lack of understanding of the purpose of reporting systems. However, a review of these studies found only two that had adopted relevant theory to underpin the investigation; a study using the theory of planned behaviour to explain the mechanisms behind nurses intention to report ADRs [25]; and a study adopting the theory of satisfaction of needs to investigate predictive factors of reporting among community pharmacists [26].

Patient and public reporting of ADRs has also been investigated, although a large part of this research has focussed on the value of patient and public reporting to health systems [1, 6, 27, 28]. Such studies have included a 2017 systematic review [1], and numerous retrospective analyses evaluating the quality and characteristics of ADR reports by patients and public compared against those submitted by healthcare professionals [6, 27, 28].

Further studies [12, 29,30,31,32,33], including one systematic review [34], investigating the factors of patient and public reporting of ADRs have largely reported similar findings as those reported with healthcare professionals, and similarly, there has been little consideration of adopting theory to underpin these investigations.

A range of strategies that have attempted to address the high-rate of underreporting of ADRs in both healthcare professionals, and patients and public, have been reported in the literature [35, 36]. Two recent systematic reviews, one of which including a meta-analysis, reported on the effectiveness of interventions for improving ADR reporting by patients and public and healthcare professionals [35, 36]. Both reviews indicated that a range of strategies may be effective in increasing ADR reporting however, there is limited evidence of sustained improvement once the intervention ceases. Furthermore, Paudyal et al.’s review goes further to call for the need to develop and test theory-based interventions, since they point out that there is an accumulation of evidence that theory-based interventions are more likely to yield positive and sustainable results compared to pragmatic approaches [35]. These conclusions align with the UK Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance for the development and evaluation of complex interventions, which places emphasis on the importance of drawing on evidence and theory and specifying key steps in the intervention development process [37].

The Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [14] is one such theoretical framework that has that has been extensively and successfully adopted in healthcare practice research to investigate the various interacting components of specific behaviours. Beyond this, The Behavioural Change Wheel (BCW) builds upon the MRC guidance and provides a practical guide of how to develop theory and evidence based intervention [38]. The BCW is a systematic tool for designing complex interventions to understand behaviour(s), identify the theoretical process to facilitate behaviour change and specify intervention content [38]. Fundamental to the BCW is an appreciation that ‘Behaviour’ is influenced by an individual, or systems, ‘Capability, Opportunity and Motivation’ (COM-B model). The COM-B elements can further be mapped to theoretical constructs using the Theoretical Domains Framework (TDF) [39].

Aim

The aim of this systematic review was to collate, summarize and synthesize the reported behavioural determinants using the TDF, that influence patient and public reporting of ADRs.

Method

This systematic review was guided by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis (PRISMA) guidelines [40].

This systematic review protocol was pre-registered in Open Science Framework database (OPS) (Registration Number: 5J7WR) [41].

Eligibility criteria and study selection

The review used the PICO framework to structure the eligibility criteria (Comparator was not relevant):

-

Population: Adult (aged 16 years or over) patients, participants, and/or members of the public;

-

Intervention: ADR reporting;

-

Outcomes: Views, attitudes and/or knowledge.

All study designs were eligible for inclusion, except for reviews, letters, and editorials.

No date limitations were applied to the search; only studies published in English were included.

Information sources and search strategy

An electronic database search was independently conducted by two authors on 25th October 2021. Five databases were systematically searched: PubMed, CENTRAL, EMBASE, Web of Science and CINAHL. Relevant medical subject headings (MeSH) and the detailed search strategies are provided in Supplementary File A. Reference lists of included studies were manually checked. The search included all articles published in English language since inception.

Selection process

Pre-implementation studies, and studies which included pooled data from investigations that included other stakeholders (e.g. healthcare professionals) were excluded. Both title/abstract and full-text screening were completed by two independent authors and discrepancies were resolved by consulting a third author. All eligible articles were transferred to ENDNOTE 7 software for duplicates to be removed.

Data collection process

A data extraction tool was developed using Excel software, extracting details of study design, country, year of publication, objective of the study, participants, description of data collection method, description of patient ADR reporting system, outcomes of the ADR reporting systems and the factors of patients and public ADR reporting.

Risk of bias assessment

The Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) checklists were used to critically appraise the cross-sectional and qualitative studies [42], while the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to appraise mixed methods studies [43]. The critical appraisal was independently conducted by two researchers, any disagreements were resolved by discussion with a third author.

Data synthesis

The theoretical domains framework (TDF), a comprehensive framework derived from 33 psychological theories and 128 theoretical constructs and organized into 14 domains [14] was employed to classify the extracted data. Two researchers with experience using the TDF worked independently to classify the data into enablers and barriers (ZN and LS). To ensure consistent interpretation of the domains, continued reference was made to the original article describing the development of the TDF [14]. In assigning the data to the most relevant TDF domain, relevant contextual information reported for an individual barrier/enable were cross-referenced to TDF constructs to check for alignment.

Where disagreement arose, the two authors met to discuss. If the disagreement could not be resolved, a third experienced member of the research team (DS) was consulted, and discussions continued until consensus was reached. There were two main disagreements between the authors regarding the classification of two barriers/enablers into the most relevant TDF domains; one barrier that was aligning both to beliefs about consequence and goals; and one enabler that was aligning to both to intentions and goals.

Results

Search outcomes

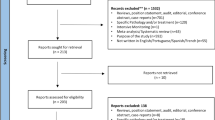

Twenty-six articles met the inclusion criteria [14, 29, 33, 44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram. See electronic Supplementary File A, which provides further detail of study exclusion following full-text review. All studies were of cross-sectional design, adopting either qualitative (n = 7) or quantitative methods (n = 13); six articles adopted mixed methods. None of the studies had adopted relevant theories to support their investigations. Details of excluded studies with reasons of exclusion in electronic Supplementary File B.

Study characteristics

Studies were published between 2008 and 2021, and were conducted in a range of countries; Saudi Arabia (n = 3) [49, 55, 57], United Kingdom (n = 4) [44, 58, 63, 64], USA (n = 2) [52, 53], Ghana (n = 3) [29, 48, 66] with remaining studies from South Korea [33], Netherlands [50, 62], Thailand [47], Canada [49], and Australia [14, 45, 59]. Detailed study characteristics are presented in Table 1.

Four studies conducted in the UK investigated patients and public’ perceptions of the National Yellow Card Scheme (YCS) [44, 58, 63, 64]. Similarly, further studies, included investigations of national reporting systems and provided a description of the reporting system and the process for patient and public reporting, however, there were 7 studies in which such details were excluded or minimally reported [45, 47, 49, 54, 57, 59, 65].

There was also considerable diversity in the number of participants involved in the included studies, cross-sectional quantitative studies ranged between 84 and 2484 participants; qualitative studies ranged between 15 and 78 participants. Participants included in the studies were either members of the public, patients who had experienced ADRs previously (buy not necessarily reported it), or participants who were retrospectively approached following submission of their ADR through an ADR reporting system. Further detail of the ADR reporting systems and study participants are presented in electronic Supplementary File C.

Risk of bias assessment

Risk of bias using the JBI checklist indicated that the influence of the researchers on the methodology in qualitative studies was not always reported [58, 64]. Within cross-sectional quantitative studies, reporting the assessment of confounding factors was frequently absent [48, 49, 54]. Assessment of mixed-methods studies using the MMAT tool revealed that the majority of studies were of high quality; however, one study did not perform sample size calculations, which drew some concerns regarding the external validity and generalizability of data [44]. Risk of bias results for both JBI and MMT tool represented in electronic Supplementary file D.

Coding of factors influencing patients and public ADR reporting

A total of twelve TDF domains resonated from factors reported in the included articles. Examples of each domain are represented in Tables 2 and 3. The TDF domains memory, attention and decision processes and behavioral regulations did not seem to be implicated in patient and public reporting of ADRs.

Knowledge: Four studies reported factors that were mapped to knowledge; patients and public often lacked adequate understanding and knowledge about ADR self-reporting systems and the purpose of these systems. Studies were cross-sectional quantitative and qualitative that indicated patients and the public were aware of the available ADR reporting systems and the process for reporting, which subsequently encouraged reporting [52, 54, 58, 66].

Skills: One UK study preformed a cross-sectional qualitative methodology and concluded that patients who had acquired skills in reporting ADRs (either under the direction of a healthcare professional or an informed acquaintance) and had prior knowledge of how to use the Yellow Card Scheme seemed to be more motivated to submit ADR self-reports [58].

Social /professional role and identity: Seven studies reported factors influencing ADR reporting, as per our analysis, these factors were mapped to social/professional role and identity. Some studies indicated patients and the public belief that they themselves have an important role to report ADRs, and a responsibility to prevent harm and help support drug safety research [50, 52, 58, 62]. In contrast, four studies mentioned an opposing perception; patients and the public did not believe that ADR reporting is their responsibility, rather it is the healthcare providers’ duty [33, 57, 61, 62].

Beliefs about capabilities: There were conflicting reports regarding patients and the public belief in their ability to report ADRs; two studies reported positive beliefs [33, 46]; whereas, one study described that an important factor contributing to patient under-reporting was a self-perceived lack of necessary skill and inability to accurately identify ADRs [58].

Optimism: From four studies, our analysis mapped factors to optimism. Patients and the public were optimistic that their reports would help enhance drug safety and improve health systems [29, 44, 58]. Whereas one study indicated patients’ lack of optimism and belief that their reports would have no subsequent impact [33].

Beliefs about consequences: In six studies, participants indicated that they report ADRs because they recognize their importance in preventing harm and potential to positively impact on their lives [44,45,46, 62, 65, 66]. Additionally, patients and the public believed that their reports provide more information that contribute to improved medication safety [29, 47, 58, 66]. However, only three studies reported that patients and the public may avoid ADR reporting due to previous negative experiences such as dismissal, denial, and lack of feedback from the ADR reporting system [33, 56, 60].

Reinforcements: Three studies reported other stimuli that encouraged patient and public reporting, these included intolerable and severe drug reactions that impact daily living, and if patients and the public perceived the need for additional medical care to resolve the drug reaction [56, 60, 63].

Intentions: One study reported patients’ intention to report so to have a voice in sharing their concerns directly with the ADR reporting agency, without interference from healthcare professionals [58].

Goals: Two studies indicated that patient aim to provide information about ADRs that are not mentioned in the patient leaflets; therefore, they tend to report their ADRs whenever it occurs [29, 50].

Environmental context and resources: Three studies mentioned that when patients and the public received specific directions and reminders from healthcare providers, they were more motivated to report their suspected ADR [49, 55, 58]. Based on the analysis, these factors were mapped to environmental context and resources. However, practitioners’ dismissive attitudes; the cost of accessing the ADR reporting system; were environmental factors that discouraged patients and the public from reporting [44, 58, 60]. Additionally, one study mentioned that having an ADR system that is easily and freely accessible and not limited to clinic-opening times was preferred [55]. Participants across various investigations agreed that a system that was easily and freely accessible, that was not limited to clinic-opening times was preferred [47, 48, 54]. Two studies reported that the use of technology such as mobile phones or web-based platforms were more preferred than paper-reports with an integrated function to provide feedback following submissions of reports [47, 48].

Social influences: Patient self-reporting was encouraged by family members and healthcare providers [29, 56].

Emotion: Two studies revealed that patients and the public anxiety resulting from suffering an ADRs is what encouraged them to report [50, 53]. Moreover, patients and the public annoyance and dissatisfaction with practitioners’ response; motivated them to report [46, 58]. In contrast, one article mentioned that patients indicated feeling embarrassed to report specific ADRs may have prevented them from reporting [51].

Discussion

Key findings

This systematic review has elucidated the key behavioral determinants relating to patient reporting of ADRs as reported in the literature. Under-reporting by patients and the public of ADRs is well documented, this review identified factors that aligned to 12 of the 14 TDF domains. Social role and identity; beliefs about consequences; knowledge; environment context and resources, were the domains that were most frequently identified to either positively or negatively influence reporting.

There were no noticeable contrasting trends in findings reported from the various countries or settings; similarly both findings derived from qualitative, quantitative or mixed-methods studies were not distinctly dissimilar.

Most studies were found to be of high quality and low-risk of bias. However, this finding should be considered in consideration of the heterogeneity between various tools that were used. The JBI checklist [41] offers a more comprehensive set of criteria than the MMAT; thus as well as the MMAT increasing the need for interpretation, its cumulative critical appraisal provides a less detailed evaluation.

Strengths and weaknesses

This review is the first to adopt behavioural theory to investigate and synthesize reported influencers of patient and public reporting of ADRs. These findings facilitate elucidation of key issues to be considered in refining existing structures and processes and increase the effectiveness of patient and public reporting ADR systems.

In terms of the study limitations, the search was limited to studies published in English or where an English translation was available. Secondly, the review excluded studies that investigated the factors of ADR reporting in population samples that included both patients and the public, and healthcare professionals with pooled findings, where it was not possible to distinguish the specific factors of each of these populations. It should be mentioned, however, that such studies were few and included small sample sizes.

Interpretation

This review builds on the existing knowledge base and provides deeper insights into the issues regarding patient and public reporting ADRs. Whilst some of the findings, such as: participant’s confusion as to who’s responsibility it is to report ADRs and to whom; patients and the public belief that reporting may prevent similar ADRs in others; that reporting would subsequently improve drug safety; and that reporting may improve the practice of health care; are similar to those reported in previous studies [29,30,31,32,33, 56]. This study has provided rich description regarding the TDF domains which influence reporting.

Many of the included studies reported patient and public uncertainty regarding reporting, which was mapped to the TDF domains knowledge and social role and identity. Further studies are warranted to understand why patients and the public experience this uncertainty, and to investigate a possible link to reports of healthcare professionals’ sub-optimal knowledge, attitudes, time constraints and lack of motivation regarding ADR reporting [9,10,11, 67, 68]. Recent literature has advocated that healthcare providers have a responsibility to enhance patients and the public awareness and understanding of their role through various methods such as sending them reminders and face-to-face educational sessions [35]. Furthermore, multiple studies reported patients and the public belief that their reports would contribute to subsequent improvements in drug safety and/or health care delivery, which was mapped to the TDF domain beliefs about consequences. An akin approach that has proved successful in encouraging healthcare professionals to report ADRs is dissemination by email of submitted reports, such investigations have not been conducted with patients and the public [69,70,71].

The TDF domain environment context and resources, captured the various reports which emphasized the patients and the public preference for a reporting system that is cost-free, easily accessible and confidential. A digital platform was also proposed several times by study participants. Such characteristics are in-line with WHO guidelines that suggests that reporting for general public should be easy and cheap [72]. Moreover, Leonardi’s Methodological Guidelines for the Study of Materiality and Affordances, discusses the need to recognise such characteristics (and others) of digital technologies in order to engage users and promote usability [73].

Further interventions aimed at improving ADR reporting rates have been reported in a 2020 systematic review and meta-analysis, which revealed that of the 28 included studies, the vast majority were educational interventions aimed at healthcare professionals [35]. The review commented on the lack of high-quality theory-informed interventions reported in the literature and their limited evidence of enhancing rates of reporting. Additionally, the authors emphasise the need to develop theory-based interventions, which are more likely to yield positive and sustainable results compared to pragmatic approaches.

This review has benefitted from the use of TDF to identify key behavioural domains that can be used to target in developing and/or refining patient and public reporting systems, as suggested by the UK Medical Research Council [37]. The Behaviour Change Wheel (BCW) advises which domains promote optimal strategies and designing of interventions mapped to behavioural determinants. Interventions are described as seven categories of education; persuasion; incentivisation; coercion; training; restriction; and environmental restructuring, modelling and enablement [38]. Determinants of social role and identity and beliefs about consequences are linked to reflective motivation in the BCW and may be enhanced through education, enablement and training. Similarly, the TDF determinant of knowledge is linked to psychological capability and may be enhanced through an educational intervention. Environmental context and resources is linked physical opportunities of the BCW may be enhanced through training, environmental restructuring and enablement [37, 38].

Thus, education, enablement and training are the most relevant interventions to influence reporting behaviours and enhance reporting-rates. This may be achieved through establishing accessible step-by-step instructional protocols and educational resources for patient and public reporting; promoting reporting through national awareness campaigns including education about the benefits of self-reporting; and integration into the delivery of person-centred care to enhance the advocacy from healthcare professionals [37, 38].

Also environmental restructuring which is likely to include further involvement from regulatory bodies and government support to establish mechanisms, which facilitate feedback and follow-ups on submitted reports, and implemented with the necessary modifications to regulations, legislations, and service provision [37, 38].

Further research

In light of these findings, this review may be used as a guide in future attempts to develop and refine patient and public ADR reporting system. Carefully designed interventions that further patient and public engagement; and enhance stakeholder education, awareness and attitudes towards ADR reporting, are likely to result in more increased reporting rates. Accordingly, it has been reported that countries with the highest reporting rates were found to intensively engage with consumer organisations to promote awareness and acceptance of pharmacovigilance [50]. This study also indicates the structural characteristics which may support patient and public reporting; simple and convenient access through a web-enabled platform or mobile application seem to support reporting rates. Lenoardi’s methodological guidelines has shown potential alignment with these findings to account for materiality and affordances of the reporting system [51] and may be adopted in future studies to elucidate further value.

Lastly, this study is the first to adopt the TDF to understand patients and the public behaviour towards reporting, albeit using retrospective data; future prospective studies, underpinned with behavioural theory, are also of value to corroborate findings and provide further insight. Likewise, the authors advocate for interventional studies, informed by the emerging evidence-based, and underpinned with relevant theory, to assist in developing strategies to optimise patient and public reporting.

Conclusion

This review has revealed the key behavioural determinants that influence patient and public reporting ADRs; namely, their knowledge; their sense of their social role and identity; their beliefs about the consequences of reporting; and their environmental context. These determinants can be mapped to behavioural change strategies to facilitate intervention development and enhance rates of ADR reporting.

References

Inácio P, Cavaco A, Airaksinen M. The value of patient reporting to the pharmacovigilance system: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:227–46.

van Hunsel F, de Waal S, Härmark L. The contribution of direct patient reported ADRs to drug safety signals in the Netherlands from 2010 to 2015. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2017;26:977–83.

Banovac M, Candore G, Slattery J, et al. Patient reporting in the EU: analysis of EudraVigilance data. Drug Saf. 2017;40:629–45.

Watson S, Chandler RE, Taavola H, et al. Safety concerns reported by patients identified in a collaborative signal detection workshop using VigiBase: Results and reflections from Lareb and Uppsala monitoring centre. Drug Saf. 2018;41:203–12.

Hasford J, Bruchmann F, Lutz M, et al. A patient-centred web-based adverse drug reaction reporting system identifies not yet labelled potential safety issues. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2021;77:1697–704.

Mahajan MM, Thatte UM, Gogtay NJ, et al. An analysis of completeness and quality of adverse drug reaction reports at an adverse drug reaction monitoring centre in Western India. Perspect Clin Res. 2018;9:123–6.

Matos C, Härmark L, van Hunsel F. Patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: an international survey of national competent authorities’ views and needs. Drug Saf. 2016;39:1105–16.

Programme for International Drug Monitoring. Available from: https://www.who.int/teams/regulation-prequalification/regulation-and-safety/pharmacovigilance/health-professionals-info/pidm. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Durrieu G, Jacquot J, Mège M, et al. Completeness of spontaneous adverse drug reaction reports sent by general practitioners to a regional pharmacovigilance centre: a descriptive study. Drug Saf. 2016;39:1189–95.

Lopez-Gonzalez E, Herdeiro MT, Figueiras A. Determinants of under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2009;32:19–31.

Bates DW, Cullen DJ, Laird N, et al. Incidence of adverse drug events and potential adverse drug events. Implications for prevention. ADE Prevention Study Group. JAMA. 1995;274:29–34.

van Hunsel F, Härmark L, Pal S, et al. Experiences with adverse drug reaction reporting by patients: an 11-country survey. Drug Saf. 2012;35:45–60.

Matos C, van Hunsel F, Joaquim J. Are consumers ready to take part in the pharmacovigilance system? A Portuguese preliminary study concerning ADR reporting. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2015;71:883–90.

Robertson J, Newby DA. Low awareness of adverse drug reaction reporting systems: a consumer survey. Med J Aust. 2013;199:684–6.

Jha N, Rathore DS, Shankar PR, et al. Need for involving consumers in Nepal’s pharmacovigilance system. Australas Med J. 2014;7:191–5.

Tandon VR, Mahajan V, Khajuria V, et al. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a challenge for pharmacovigilance in India. Indian J Pharmacol. 2015;47:65–71.

Khalili M, Mesgarpour B, Sharifi H, et al. Estimation of adverse drug reaction reporting in Iran: correction for underreporting. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2021;30:1101–14.

Dutta A, Banerjee A, Basu S, et al. Analysis of under-reporting of adverse drug reaction: scenario in India and neighbouring countries. IP Int J Compr Adv Pharmacol. 2020;5:118–24.

Shamim S, Sharib SM, Malhi SM, et al. Adverse drug reactions (ADRS) reporting: awareness and reasons of under-reporting among health care professionals, a challenge for pharmacists. Springerplus. 2016;5:1778.

Gupta R, Malhotra A, Malhotra P. A study on determinants of underreporting of adverse drug reactions among resident doctors. Int J Res Med Sci. 2018;6:623–7.

Haider. Factors associated with underreporting of adverse drug reactions by nurses: a narrative literature review. Medknow Publications and Media Pvt. Ltd.; 2017; Available from: https://www.saudijhealthsci.org/article.asp?issn=22780521;year=2017;volume=6;issue=2;spage=71;epage=76;aulast=Haider. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Underreporting of adverse drug reactions: Results from a survey among physicians | European Psychiatry | Cambridge Core [Internet]. Available from: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/european-psychiatry/article/underreporting-of-adverse-drug-reactions-results-from-a-survey-among-physicians/D8021AAD38020DA38873F2E6DEE27E31. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Güner MD, Ekmekci PE. Healthcare professionals’ pharmacovigilance knowledge and adverse drug reaction reporting behavior and factors determining the reporting rates. J Drug Assess. 2019;8:13–20.

Le TT, Nguyen TTH, Nguyen C, et al. Factors associated with spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting among healthcare professionals in Vietnam. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2020;45:122–7.

Angelis AD, Pancani L, Steca P, et al. Testing an explanatory model of nurses’ intention to report adverse drug reactions in hospital settings. J Nurs Manag. 2017;25:307–17.

Yu YM, Lee E, Koo BS, et al. Predictive factors of spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions among community pharmacists. PLoS ONE. 2016;11: e0155517.

van Hunsel F, Passier A, van Grootheest K. Comparing patients’ and healthcare professionals’ ADR reports after media attention: the broadcast of a Dutch television programme about the benefits and risks of statins as an example. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;67:558–64.

Rolfes L, van Hunsel F, Wilkes S, et al. Adverse drug reaction reports of patients and healthcare professionals-differences in reported information. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2015;24:152–8.

Sabblah GT, Darko DM, Mogtari H, et al. Patients’ perspectives on adverse drug reaction reporting in a developing country: a case study from Ghana. Drug Saf. 2017;40:911–21.

Yamamoto M, Kubota K, Okazaki M, et al. Patients views and experiences in online reporting adverse drug reactions: findings of a national pilot study in Japan. Patient Prefer Adherence. 2015;9:173–84.

Assanee J, Sorofman BA, Sirisinsuk Y, et al. Factors influencing patient intention to report adverse drug reaction to community pharmacists: a structural equation modeling approach. Res Soc Adm Pharm. 2022;18:2643–50.

Chen Y, Wang Y, Wang N, et al. Knowledge, attitude, and practice regarding pharmacovigilance among the general public in Western China: a cross-sectional study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2021;37:101–8.

Kim S, Yu YM, You M, et al. A cross-sectional survey of knowledge, attitude, and willingness to engage in spontaneous reporting of adverse drug reactions by Korean consumers. BMC Public Health. 2020;20:1527.

Al Dweik R, Stacey D, Kohen D, et al. Factors affecting patient reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;83:875–83.

Paudyal V, Al-Hamid A, Bowen M, et al. Interventions to improve spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting by healthcare professionals and patients: systematic review and meta-analysis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19:1173–91.

Li R, Zaidi STR, Chen T, et al. Effectiveness of interventions to improve adverse drug reaction reporting by healthcare professionals over the last decade: a systematic review. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2020;29:1–8.

O’Cathain A, Croot L, Duncan E, et al. Guidance on how to develop complex interventions to improve health and healthcare. BMJ Open. 2019;9: e029954.

Online Book. The behaviour change wheel book—a guide to designing interventions. Available from: http://www.behaviourchangewheel.com/online-book#1. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Cane J, O’Connor D, Michie S. Validation of the theoretical domains framework for use in behaviour change and implementation research. Implement Sci. 2012;7:37.

PRISMA. Available from: https://prismastatement.org/PRISMAStatement/Checklist.aspx. Accessed 10 Nov 2022.

Shafei L, Nazar Z, Alhathal T, et al. Influencers and outcomes of patient reporting adverse drug reactions: A systematic review. [Internet]. https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/5J7WR. Accessed 31 Mar 2023.

Critical Appraisal Tools | JBI [Internet]. Available from: https://jbi.global/critical-appraisal-tools. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) Version 2018 User Guide | NCCMT [Internet]. Available from: https://www.nccmt.ca/knowledge-repositories/search/232. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Anderson C, Krska J, Murphy E, et al. Yellow Card Study Collaboration. The importance of direct patient reporting of suspected adverse drug reactions: a patient perspective. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72:806–22.

Adisa R, Adeniyi OR, Fakeye TO. Knowledge, awareness, perception and reporting of experienced adverse drug reactions among outpatients in Nigeria. Int J Clin Pharm. 2019;41:1062–73.

Ashoorian DM, Davidson RM, Rock DJT, et al. Development of the My Medicines and Me (M3Q) side effect questionnaire for mental health patients: a qualitative study. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2015;5:289–303.

Jarernsiripornkul N, Patsuree A, Krska J. Public confidence in ADR identification and their views on ADR reporting: mixed methods study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;73:223–31.

Sabblah GT, Darko D, Härmark L, et al. Patient preferences and expectation for feedback on adverse drug reaction reports submitted in Ghana. Ghana Med J. 2019;53:150–5.

Sales I, Aljadhey H, Albogami Y, et al. Public awareness and perception toward adverse drug reactions reporting in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. Saudi Pharm J. 2017;25:868–72.

van Hunsel F, van der Welle C, Passier A, et al. Motives for reporting adverse drug reactions by patient–reporters in the Netherlands. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2010;66:1143–50.

Fortnum H, Lee AJ, Rupnik B, et al. Yellow Card Study Collaboration. Survey to assess public awareness of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions in Great Britain. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:161–5.

McAuley JW, Chen AY, Elliott JO, et al. An assessment of patient and pharmacist knowledge of and attitudes toward reporting adverse drug events due to formulation switching in patients with epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav. 2009;14:113–7.

Oladimeji O, Farris KB, Urmie JG, et al. Risk factors for self-reported adverse drug events among medicare enrollees. Ann Pharmacother. 2008;42:53–61.

Cheema E, Sutcliffe P, Singer DR. Gaining insight into patients’ medications and their self-reported experience of adverse drug reactions: a cross sectional study in the emergency department. Int J Pharm Sci Res. 2018;46:2067–72.

Kassem LM, Alhabib B, Alzunaydi K, et al. Understanding patient needs regarding adverse drug reaction reporting smartphone applications: a qualitative insight from Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18:3862.

Al Dweik R, Yaya S, Stacey D, et al. Patients’ experiences on adverse drug reactions reporting: a qualitative study. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2020;76:1723–30.

Islam MA, Al-Karasneh AF, Naqvi AA, et al. Public awareness about medicine information, safety, and adverse drug reaction (ADR) reporting in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. Pharmacy. 2020;8:E222.

Arnott J, Hesselgreaves H, Nunn AJ, et al. What can we learn from parents about enhancing participation in pharmacovigilance? Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75:1109–17.

Braun LA, Tiralongo E, Wilkinson JM, et al. Adverse reactions to complementary medicines: the Australian pharmacy experience. Int J Pharm Pract. 2010;18:242–4.

Bukirwa H, Nayiga S, Lubanga R, et al. Pharmacovigilance of antimalarial treatment in Uganda: community perceptions and suggestions for reporting adverse events. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13:1143–52.

Elkalmi R, Hassali MA, Al-Lela OQ, et al. Adverse drug reactions reporting : Knowledge and opinion of general public in Penang, Malaysia. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2013;5:224–8.

Härmark L, Lie-Kwie M, Berm L, et al. Patients’ motives for participating in active post-marketing surveillance. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2013;22:70–6.

Krska J, Jones L, McKinney J, et al. Medicine safety: experiences and perceptions of the general public in Liverpool. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2011;20:1098–103.

Lorimer S, Cox A, Langford NJ. A patient’s perspective: the impact of adverse drug reactions on patients and their views on reporting. J Clin Pharm Ther. 2012;37:148–52.

Jha N, Rathore DS, Shankar PR, et al. Pharmacovigilance knowledge among patients at a teaching hospital in Lalitpur District, Nepal. J Clin Diagn Res. 2014;8:32–4.

Jacobs TG, Hilda Ampadu H, Hoekman J, et al. The contribution of Ghanaian patients to the reporting of adverse drug reactions: a quantitative and qualitative study. BMC Public Health. 2018;18:1–11.

Hazell L, Shakir SAW. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions : a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006;29:385–96.

Varallo FR, Guimarães SDOP, Abjaude SAR, et al. Causes for the underreporting of adverse drug events by health professionals: a systematic review. Rev Esc Enferm U P. 2014;48:739–47.

Johansson M-L, Brunlöf G, Edward C, et al. Effects of e-mails containing ADR information and a current case report on ADR reporting rate and quality of reports. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:511–4.

Adams SA. Using patient-reported experiences for pharmacovigilance? Stud Health Technol Inform. 2013;194:63–8.

Ribeiro-Vaz I, Silva A-M, Costa Santos C, et al. How to promote adverse drug reaction reports using information systems—a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:27.

World Health Organization. Safety monitoring of medical products: reporting system for the general public [Internet]. World Health Organization; 2012. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/336225. Accessed 8 Nov 2022.

Leonardi PM. Methodological guidelines for the study of materiality and affordances. Routledge Companion Qual Res Organ Stud. London: Routledge; 2017.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by the Qatar National Library. This publication was made possible by the UREP award [UREP25-068-3-020] from the Qatar National Research Fund (a member of The Qatar Foundation). The statements made herein are solely the responsibility of the authors.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interest

Derek Stewart is the Editor-in-Chief of the International Journal of Clinical Pharmacy. He had no role in handling the manuscript, specifically the processes of editorial review, peer review and decision making.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Shafei, L., Mekki, L., Maklad, E. et al. Factors that influence patient and public adverse drug reaction reporting: a systematic review using the theoretical domains framework. Int J Clin Pharm 45, 801–813 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01591-z

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11096-023-01591-z