Abstract

Spanish has two forms to introduce comparative standards: que ‘that’ and de ‘of.’ The comparative morpheme is always the same más ‘-er/more.’ While que-comparatives show no variation in their syntactic properties, there is significant variation within de-comparatives regarding extraposition, scope, ACD resolution and the syntax of comparative numerals. Despite this variation, I argue that a uniform account is possible. I propose that más has the same syntax across the board (i.e. it takes the late-merged standard as complement, Bhatt and Pancheva 2004) and semantically it is a generalized quantifier over degrees (Heim 2001). The analysis (i) ensures that más and the standard form a constituent, (ii) allows for inverse scope, ACD resolution inside the standard of comparison and extraposition.

Similar content being viewed by others

1 Introduction

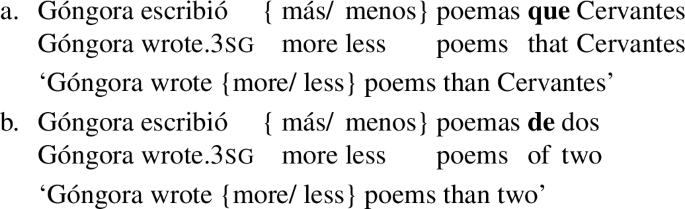

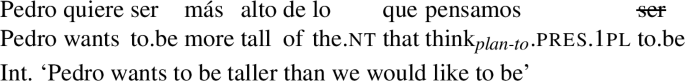

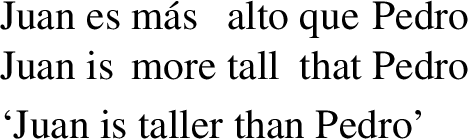

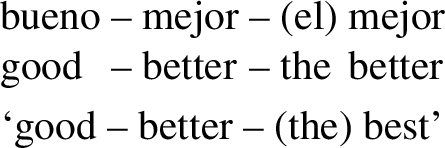

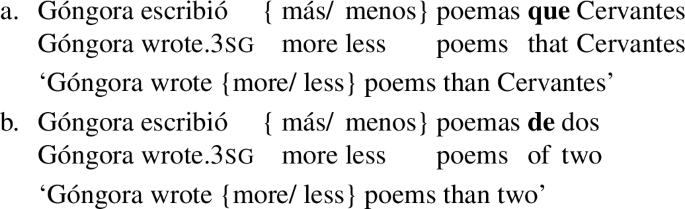

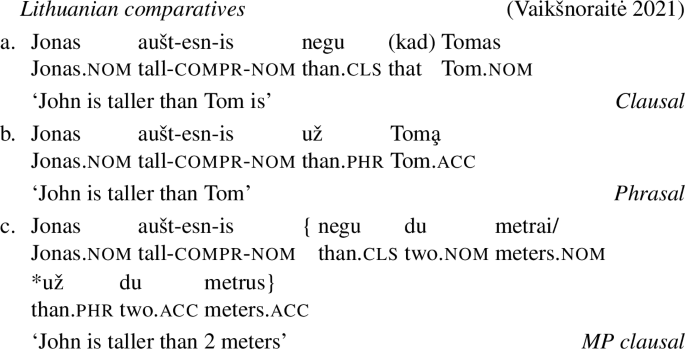

There is a great amount of variation in the expression of comparative constructions cross-linguistically. A common strategy is to morpho-syntactically differentiate the comparative morpheme, i.e. -er/more, from the standard morpheme, i.e. than (Stassen 1985; Beck et al. 2009). One such a language is Spanish where the standard of comparison can be introduced by two distinct morphemes: que ‘that’ and de ‘of.’ The comparative morpheme, however, remains always invariant: más ‘-er/more’ for superiority and menos ‘less’ for inferiority. This is illustrated in (1):Footnote 1Footnote 2

-

(1)

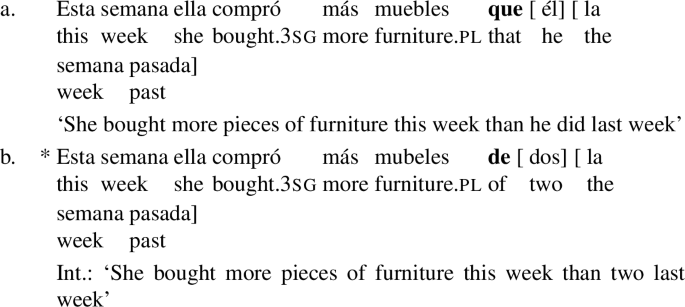

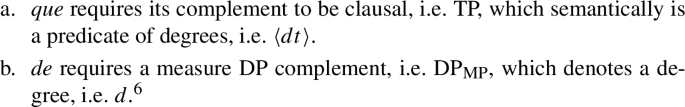

The choice of either que or de is not arbitrary but is conditioned by a series of syntactic and semantic factors (Price 1990; Brucart 2003; Mendia 2020). Que is a complementizer that selects for TPs; thus, it introduces clausal complements. This is supported by the fact that multiple constituents can co-occur inside the standard where comparative ellipsis has occurred (Bresnan 1973; Lechner 2001, 2004, 2020; Bhatt and Takahashi 2011; a.o.). On the contrary, de is a preposition and its complement must be a nominal. As a result, it is impossible to have multiple (indepdendent) constituents co-occurring inside the de-standard. This contrast is given in (2).Footnote 3

-

(2)

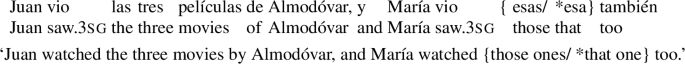

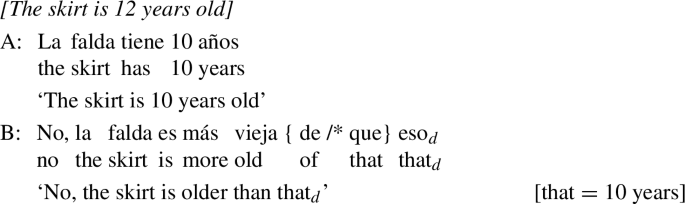

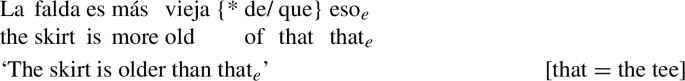

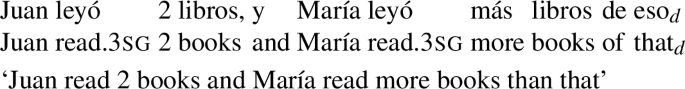

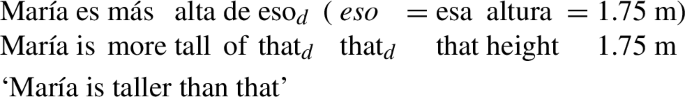

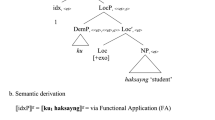

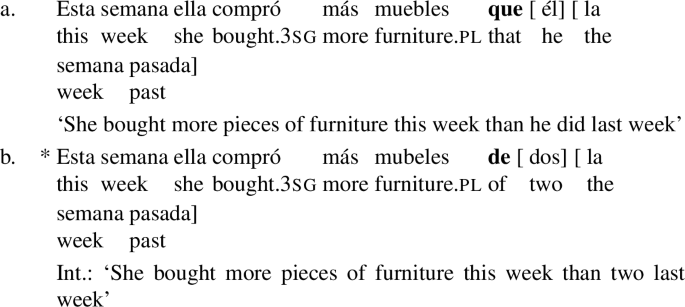

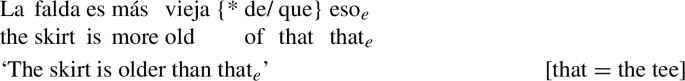

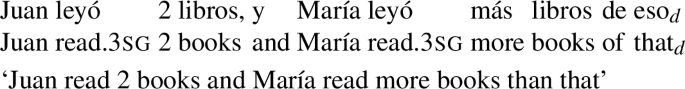

With respect to the semantics, clausal standards have been argued to involve degree-abstraction (Bresnan 1973; Heim 2001; Pancheva 2006; Beck et al. 2009), which makes them behave as predicates of degrees. The remnant constituents themselves inside the standard, though, can denote properties. This differs from de-standards which lack degree abstraction; and, the nominal complement that they introduce has to be degree-based. One way to test for this difference, as proposed by Mendia (2020), is to use the non-agreeing demonstrative pronoun eso ‘that,’ which can either make reference to an individual or to a degree. This difference is shown in (3) and (4):Footnote 4eso in (3) is making anaphoric reference to a degree (i.e. the age of the skirt); eso in (4) is referencing an individual, i.e. the tee.

-

(3)

-

(4)

[I have an old tee and an older skirt. Pointing at the tee.]

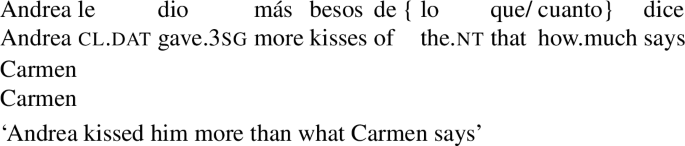

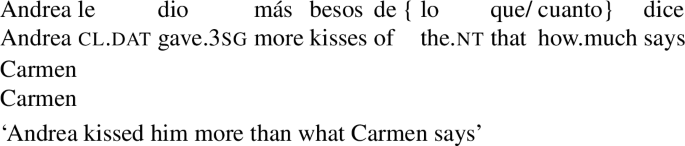

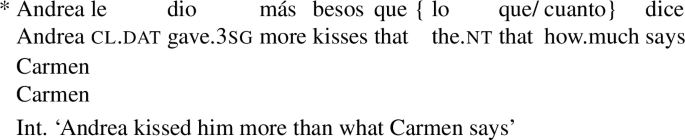

Furthermore, de is rather selective when it acts as the standard morpheme. In particular, the DP that de introduces may consist of a numeral or numerically modified NP as in (1b); a non-agreeing demonstrative pronoun making reference to degrees like in (3); or a free relative as in (5).Footnote 5

-

(5)

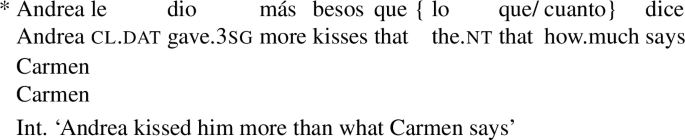

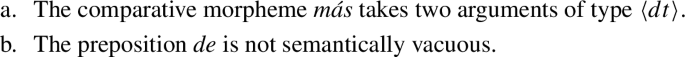

Free relatives fit the pattern of complements selected by de given that (i) they are DPs introduced by a definite or quantity determiner and (ii) are definite degree descriptions (Izvorski 1996; Donati 1997; Caponigro 2004; Gutiérrez-Rexach 2014). As a result, they are incompatible with standard morpheme que, e.g. (6).

-

(6)

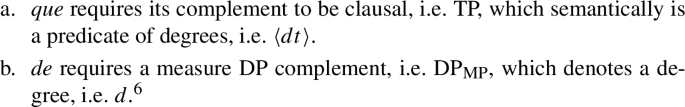

The generalizations that emerge from this discussion can be summarized in (7), slightly modified from Mendia (2020):

-

(7)

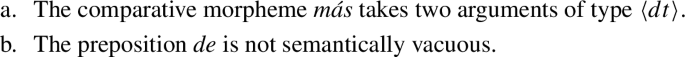

A question that (7) raises is whether a uniform analysis of the two types of comparatives is possible, considering that the standards of comparison they introduce belong to different syntactic categories, and are of a distinct semantic type. One possible answer is that such uniformity is not feasible (Mendia 2020). In this paper, I argue that not only is uniformity a more parsimonious and desired alternative but it is also empirically supported. In particular, I argue that it can be achieved by making the following two proposals:

-

(8)

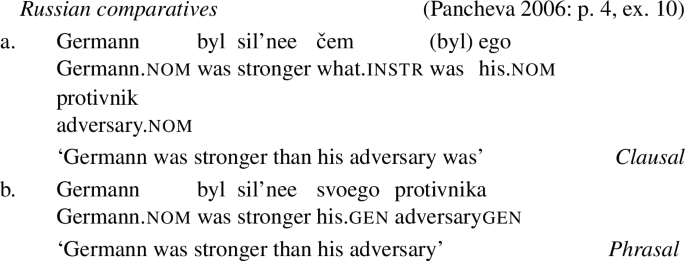

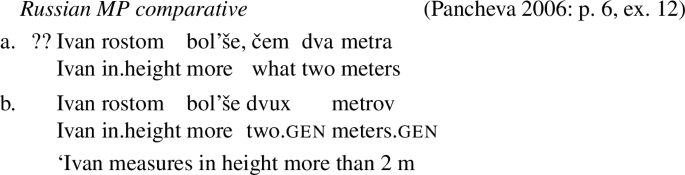

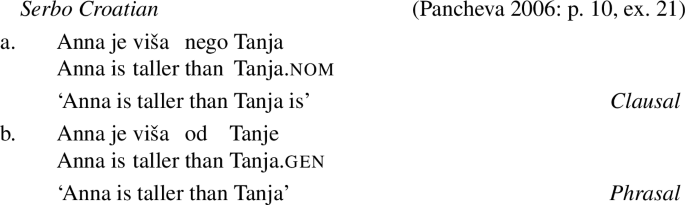

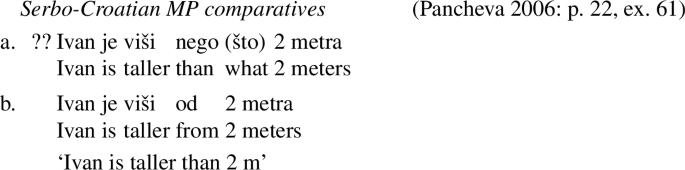

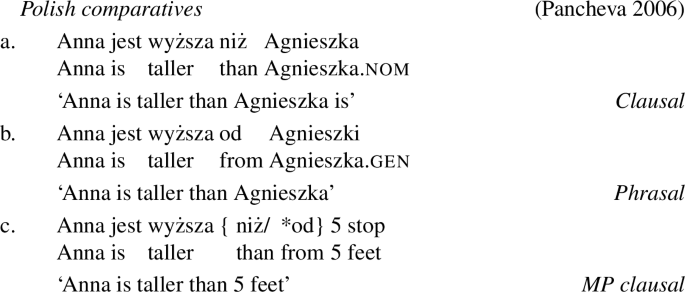

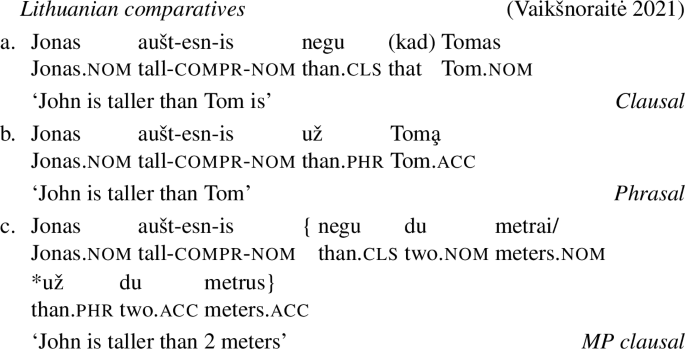

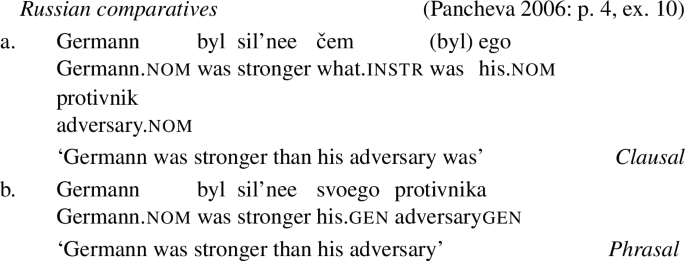

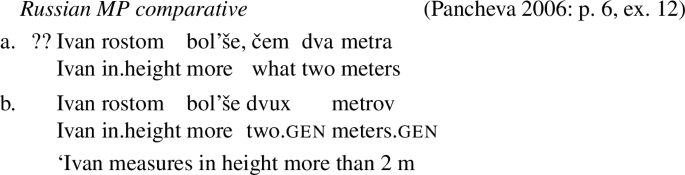

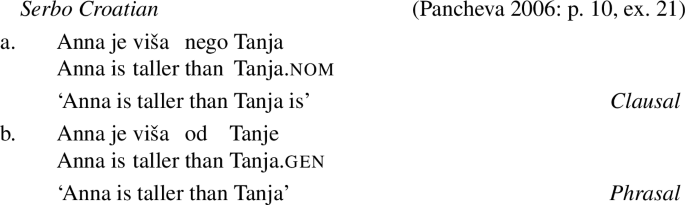

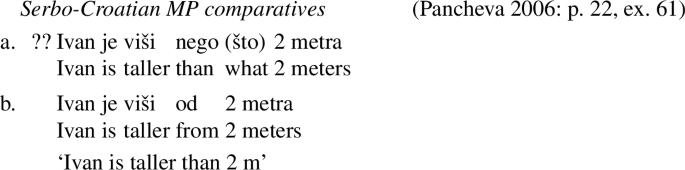

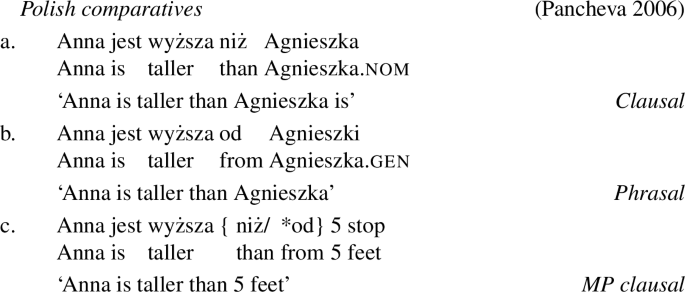

(8a) provides a uniform treatment for the comparative morpheme as a generalized quantifier over degrees, which has been independently argued for (Heim 2001; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Pancheva 2006, 2010; Lechner 2020; a.o.); and (8b) enables it (Pancheva 2006, 2010). This aligns with the cross-linguistic observations made by Pancheva (2006), Bale (2008) and Alrenga et al. (2012) that the semantics of comparison is not only encoded by the degree quantifier, but also by the standard morpheme. In fact, as they argue, in those languages that mark the phrasal vs. clausal distinction, the difference lies in the standard morpheme and not in the comparative morpheme.Footnote 6

The goal of this paper is twofold: (i) to provide a uniform syntactic analysis of comparatives in Spanish; and, (ii) to provide a full compositional semantic analysis with unified semantics for más and a semantic role for the standard morphemes. In a nutshell, I propose that, instead of being ambiguous, más should be analyzed as a Degree head that must undergo an operation of Quantifier Raising (QR) to a higher node (Heim 2001), at which point the standard is late-merged as its sister (Bhatt and Pancheva 2004). In addition, I compare the findings and predictions that the uniform analysis makes with the ones made by the non-uniform account developed in Mendia (2020). The two analyses are largely the same regarding que-comparatives, but they differ with respect to de-comparatives. I show that the non-uniform analysis faces a series of challenges that the uniform analysis does not.

The paper is organized as follows. In Sect. 2 I describe the core data for the two types of comparatives. I start to develop my proposal and delve into the details of the analysis in Sect. 3. In Sect. 4, I address the locality and height of QR, and the interactions with Scope Economy. In Sect. 5, I compare my analysis with Mendia’s (2020), and in Sect. 6 I address the Spanish data and some related cross-linguistic variation. Finally, Sect. 7 concludes the paper.

2 Core data

I first focus on que-comparatives (Sect. 2.1) and then move on to de-comparatives (Sect. 2.2). At this point I devote a subsection to discussing the relevant data for the subsequent analysis (e.g. comparative numerals, Sect. 2.2.1; extraposition into the clause, Sect. 2.2.2; inverse scope, Sect. 2.2.3; and ellipsis and ACD, Sect. 2.2.4). I then summarize the main findings in Sect. 2.3.

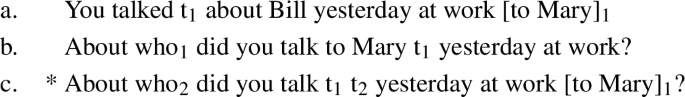

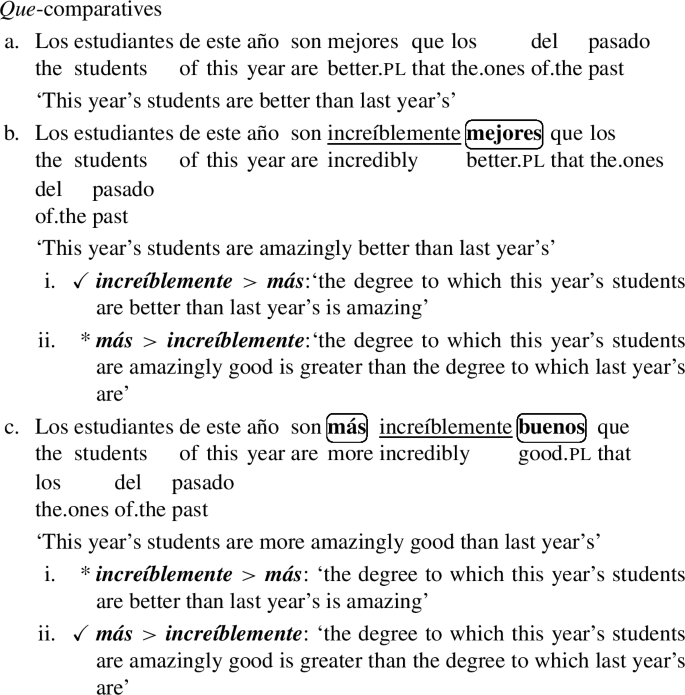

2.1 Que-comparatives

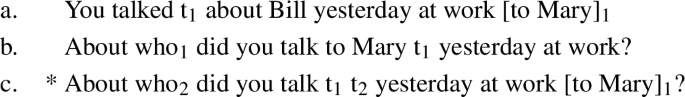

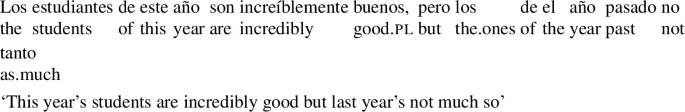

Spanish has a clausal comparative strategy which involves the comparative morpheme más and the standard morpheme que. I will refer to these as que-comparatives. One of the properties of que-comparatives is that the standard of comparison can appear extraposed into the clause. This is shown in (9):Footnote 7

-

(9)

Que-extraposition into the clause

In (9), the standard que un iPhone ‘than an iPhone’ may occupy different positions: it may precede both clausal adjuncts or appear to the right of either of them. Comparative ellipsis has applied to the embedded clause deleting everything but the remnant.

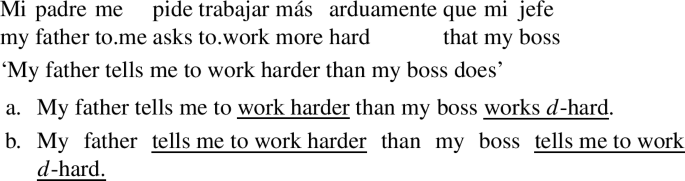

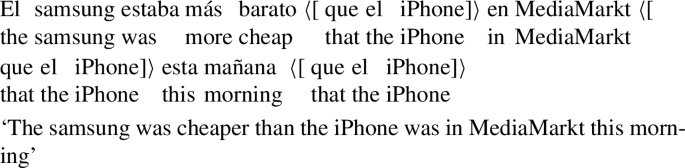

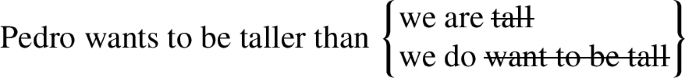

Relatedly, que-comparatives give rise to ambiguities depending on the size of the elided constituent. For example, the sentence in (10) is ambiguous between the two interpretations in (10a) and (10b).

-

(10)

The ellipsis site in (10a) is resolved by copying the non-finite clause trabjar arduamente ‘work hard,’ and what is being compared are the speaker’s working habits and the speaker’s boss’ working habits. In (10b), the ellipsis site is larger: it contains the matrix clause embedding the non-finite one. An accurate paraphrase is “my father tells me to work this hard and my boss tells me to work that hard”: this > that.

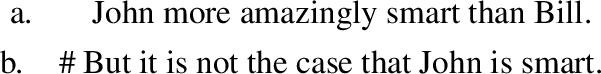

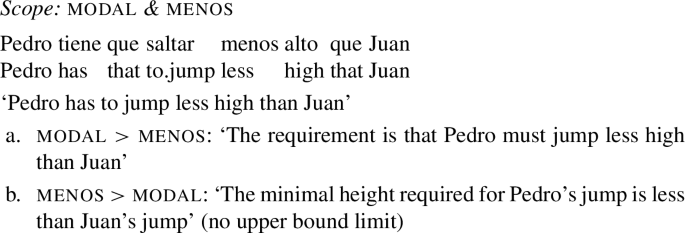

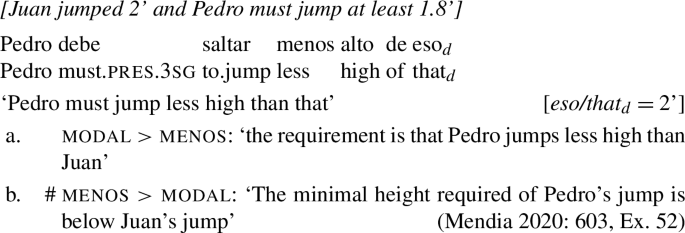

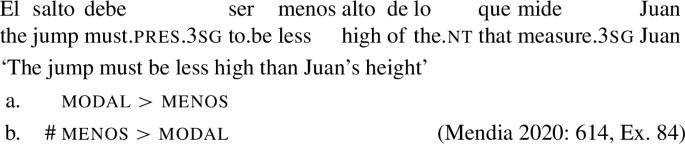

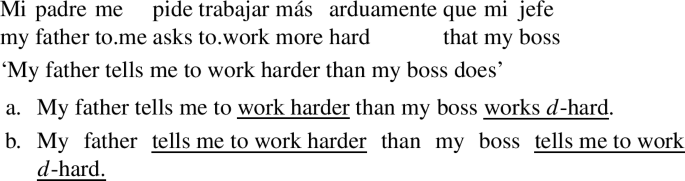

In addition to the extraposition and ellipsis resolution facts, it has been observed that comparative morphemes may take inverse scope over some quantificational elements, namely modals (e.g. Heim 2001; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Beck et al. 2009). Based on these observations, Mendia (2020) notes that the comparative morpheme más can also take inverse scope over intensional operators when the standard of comparison is introduced by que. This is shown with menos in (11).Footnote 8

-

(11)

The surface scope interpretation is a comparison of maxima: the maximal height of Juan’s jump and the maximal height of Pedro’s jump. The modal is imposing the requirement that the maximal height of Pedro’s jump cannot exceed the maximal height of Juan’s. However, the inverse scope is merely saying that Pedro is not required to jump as high as Juan, but he may do so. Both interpretations are acceptable in Spanish.

Ellipsis resolution, scope and surface position of the standard of comparison have been argued to be governed by the same underlying mechanism. In fact, as observed first by Sag (1976), Williams (1974, 1977) and subsequently by Bhatt and Pancheva (2004), there is a correlation between the size of the ellipsis and scope of the DegP. This generalization is known as the Ellipsis-Scope Generalization, formulated as in (12).

-

(12)

The Ellipsis-Scope Generalization

The scope of a DegP containing elided material must contain the antecedent of the ellipsis.

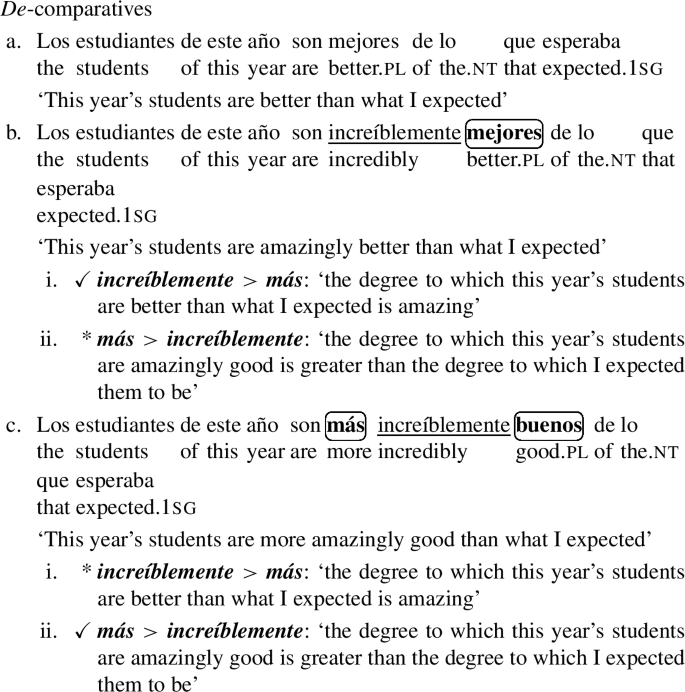

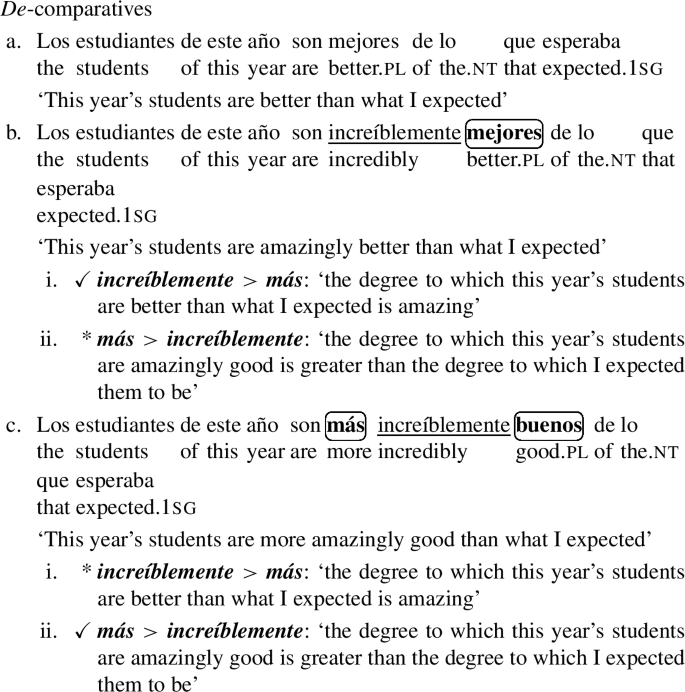

2.2 De-comparatives

In addition to que, the standard of comparison can also be introduced by the preposition de. I will refer to these as de-comparatives. An immediate question is whether más…de comparatives exhibit the same syntactic properties as their que counterparts. I will show that, while they do, there are important differences between the two types of comparative constructions. This variation seemingly questions a uniform analysis.

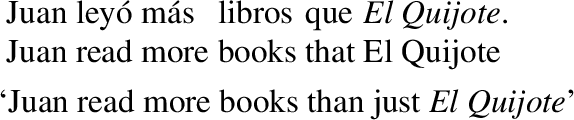

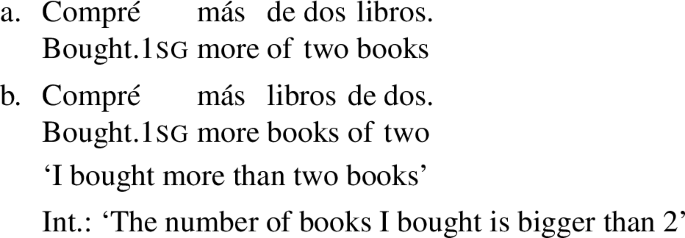

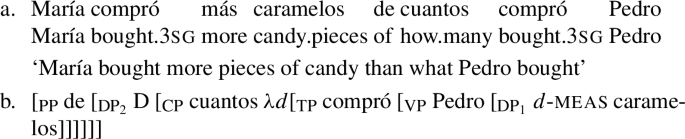

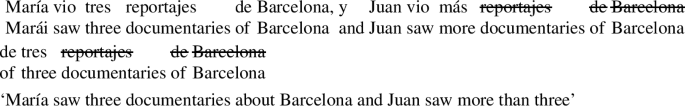

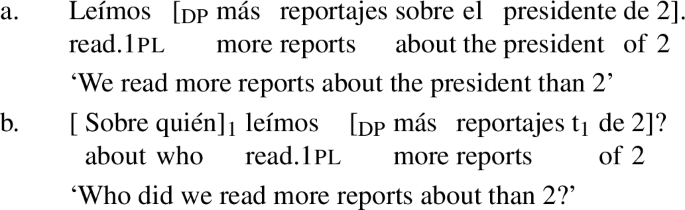

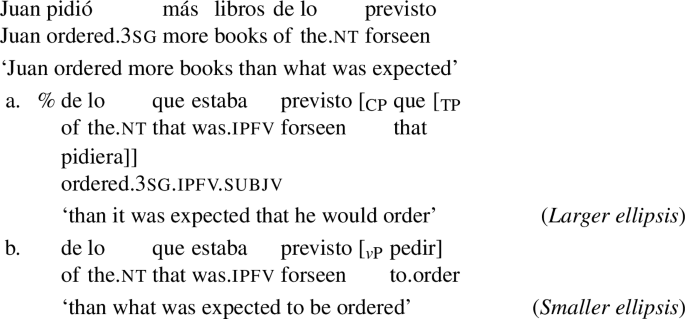

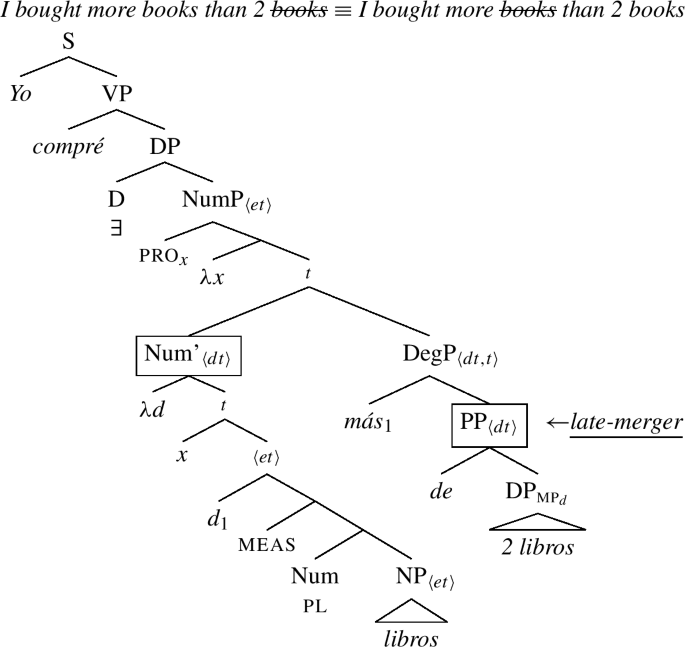

2.2.1 Comparative numerals

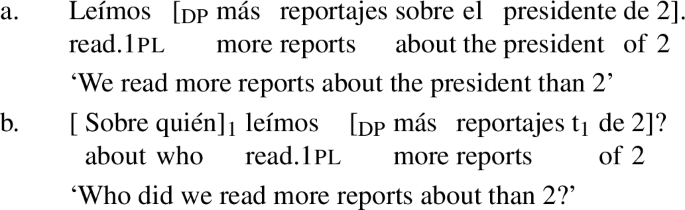

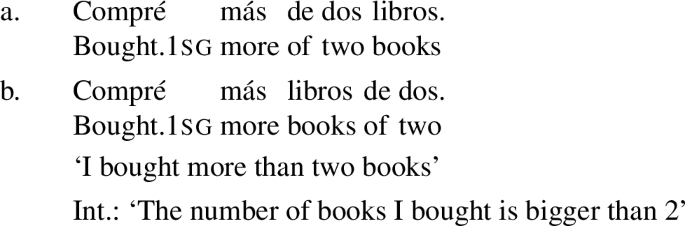

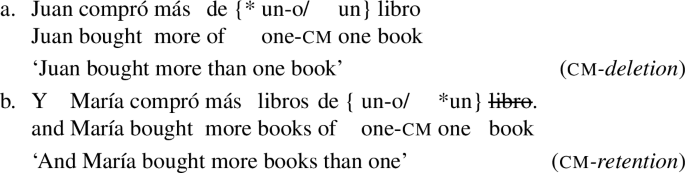

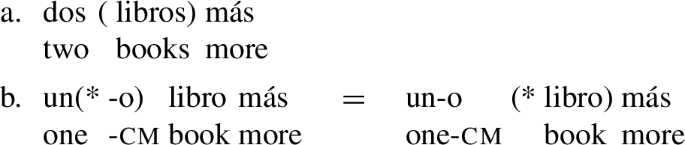

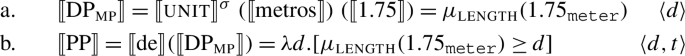

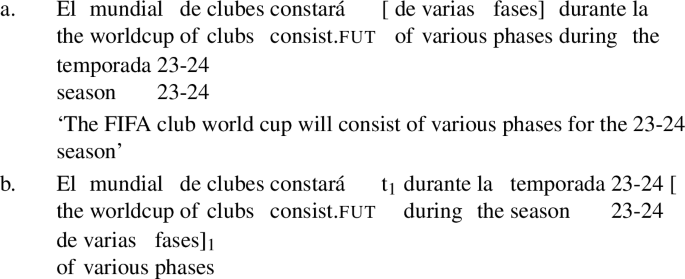

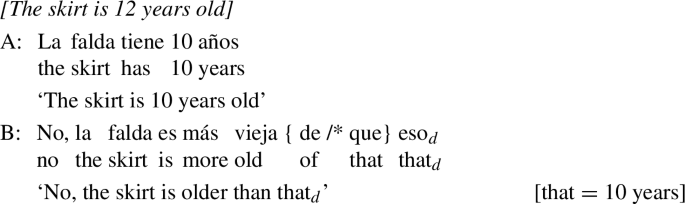

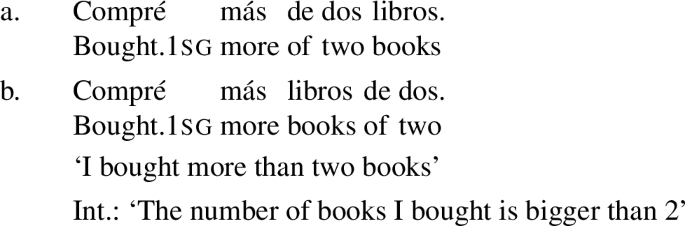

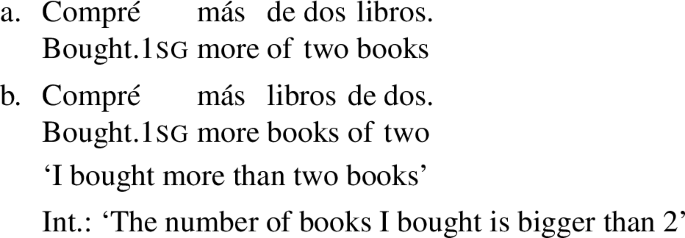

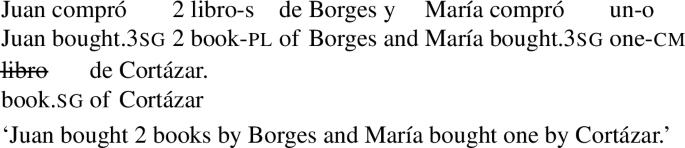

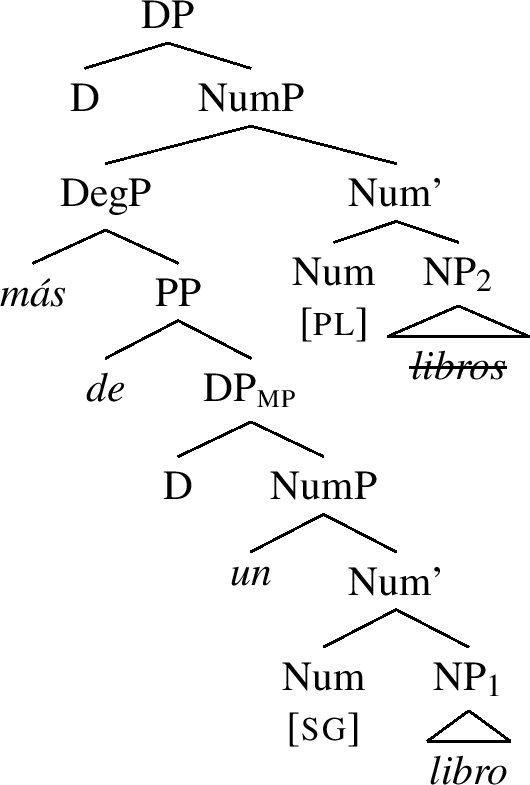

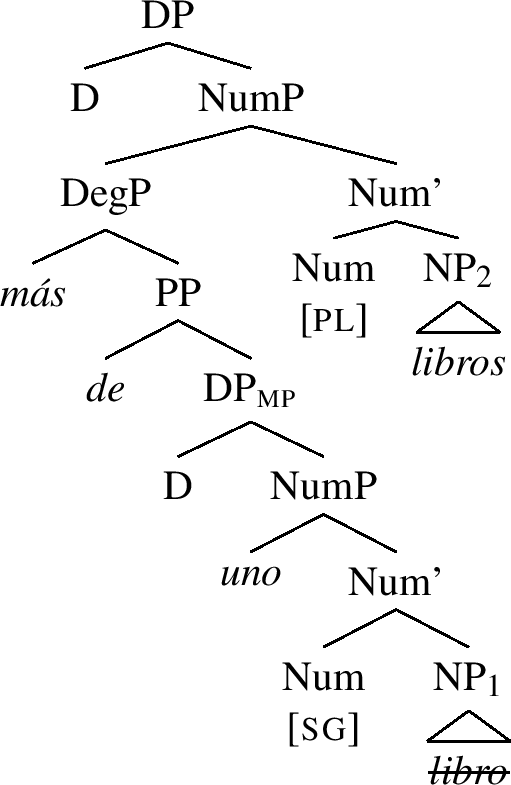

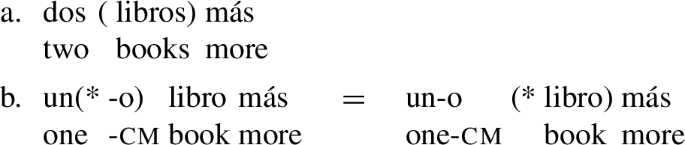

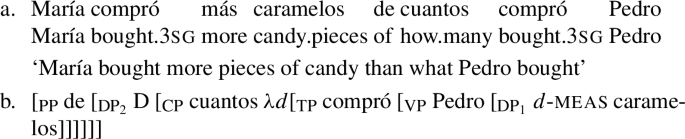

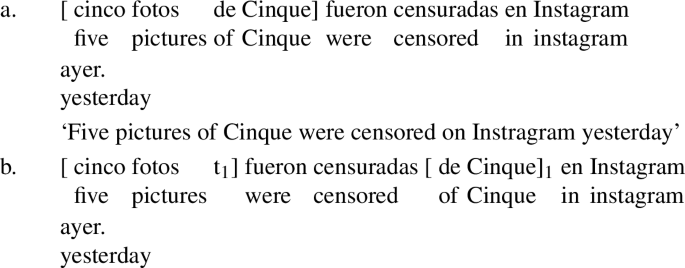

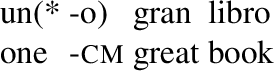

Nominal comparatives that have a numeral/numerically modified noun inside the standard are referred to in the literature as comparative numerals (Arregi 2013). One of the hallmark properties of de-comparatives is that numerals or numerically modified nouns can appear inside the standard. An example taken from Brucart (2003: p. 44, ex. 55a–b) is given in (13):

-

(13)

The sentences in (13) are truth-conditionally equivalent: ‘the number of books that I bought is bigger than 2’; but they differ on the surface depending on whether the NP libros ‘books’ is immediately adjacent to the numeral in (13a) or immediately adjacent to más in (13b).

Comparative numerals with de raise questions about DP-internal constituency, as well as the relation between más and the standard. In particular, what is the underlying structure of comparative numerals? And, are there two separate NPs underlyingly or just one? In order to provide a complete analysis of comparative constructions, and more specifically de-comparatives we must make headway in our understanding of comparative numerals.

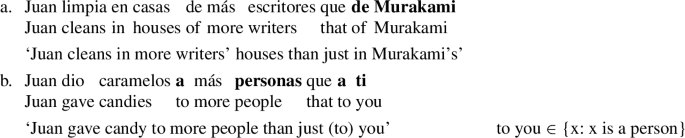

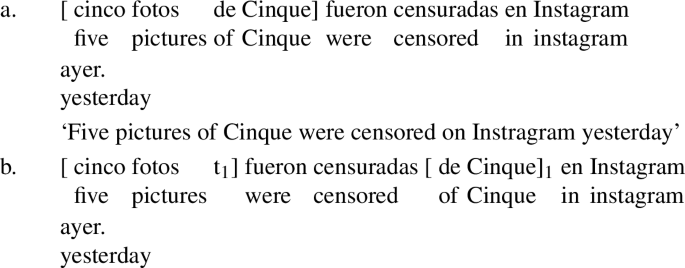

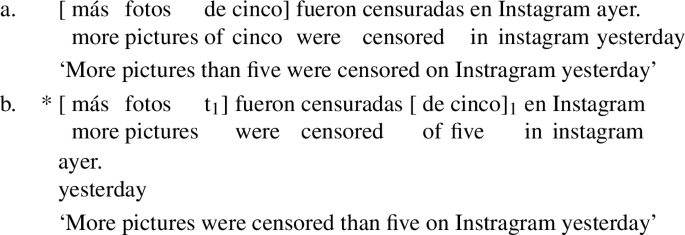

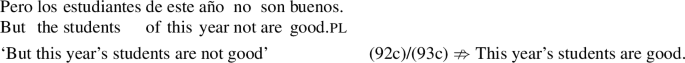

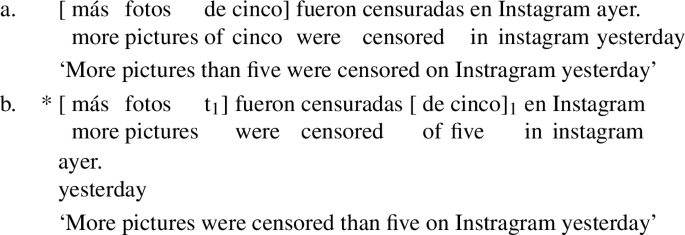

2.2.2 Extraposition into the clause

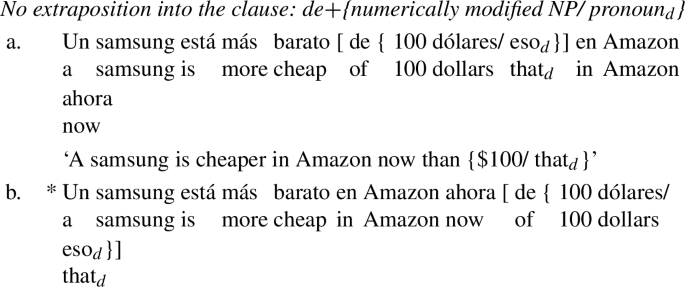

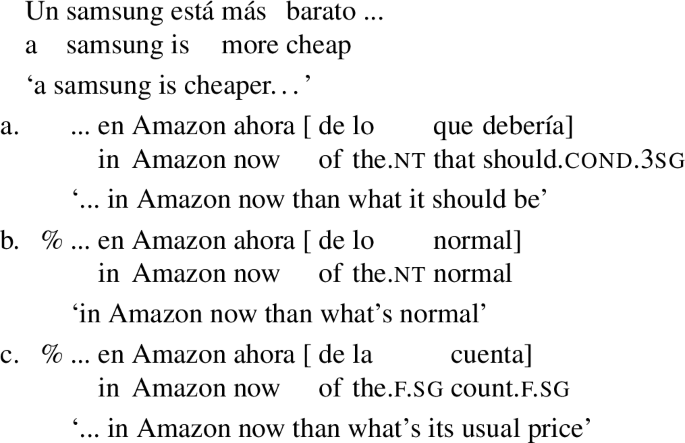

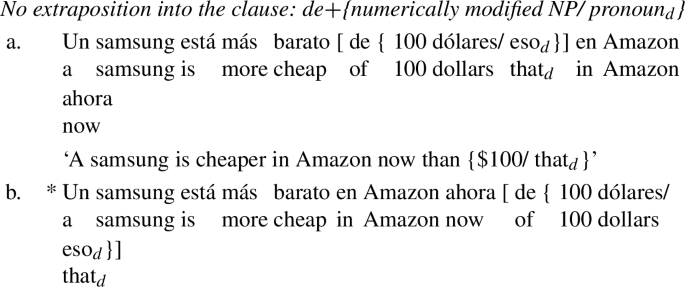

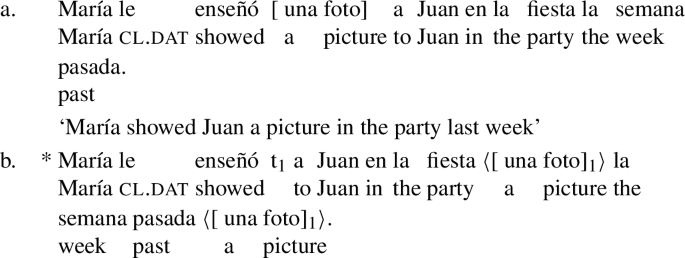

The second set of challenging data is concerned with extraposition. Namely, extraposition of de-standards into the clause is not acceptable when the complement of de is a numeral/numerically modified NP or a degree-denoting pronoun. This is shown in (14):

-

(14)

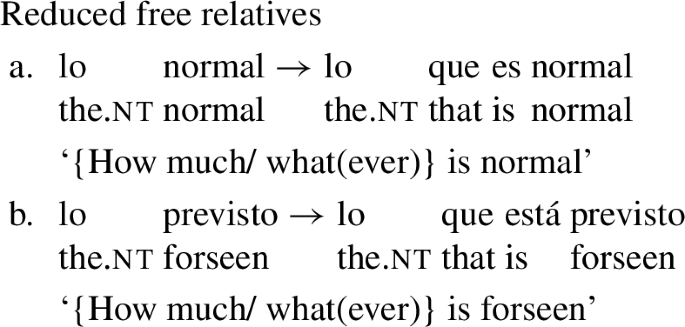

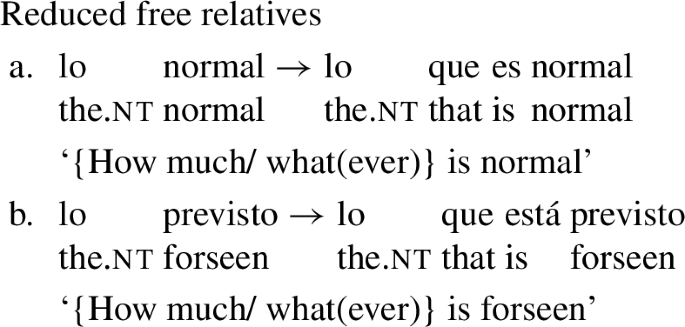

While it is true that the ungrammaticality of (14) is indisputable, we should not generalize that all de-standards cannot appear extraposed into the clause. In fact, there is a subset of de-standards that can. These include free relatives, both full (16a) and reduced (16b–16c).Footnote 9 By reduced free relatives I refer to those free relative constructions that lack an overt verbal projection. They typically consist of a definite determiner and a predicate, as in (15):

-

(15)

-

(16)

Extraposition into the clause: Full & reduced free relatives

The examples in (16) show that extraposition is not limited to que-comparatives (contra Mendia 2020); de-standards may appear extraposed into the clause as well. The data, in fact, suggest the generalization in (17):Footnote 10

-

(17)

The generalization prohibits extraposition into the clause of (14) since the standard is composed of a numerically modified NP or a degree-denoting pronoun; but crucially it does not rule out (16) with a free relative. We must then explain what restricts the two types of más…de discontinuity.Footnote 11

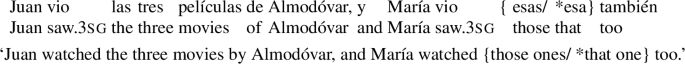

2.2.3 Inverse scope

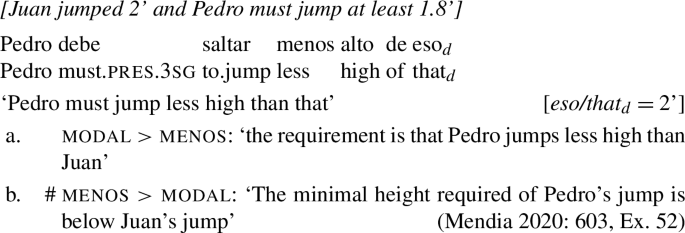

A third challenge is the variation in inverse scope. Mendia (2020) has reported, based on data like (18)–(19), that inverse scope between the degree morpheme and a modal is not possible when the standard is introduced by de. The data and the judgments are Mendia’s:

-

(18)

-

(19)

(18) and (19) do not allow the inverse scope interpretation with the lower bound. On the face of data like these, Mendia (2020) concludes that más does not interact with modals for scope when the standard is introduced by de.

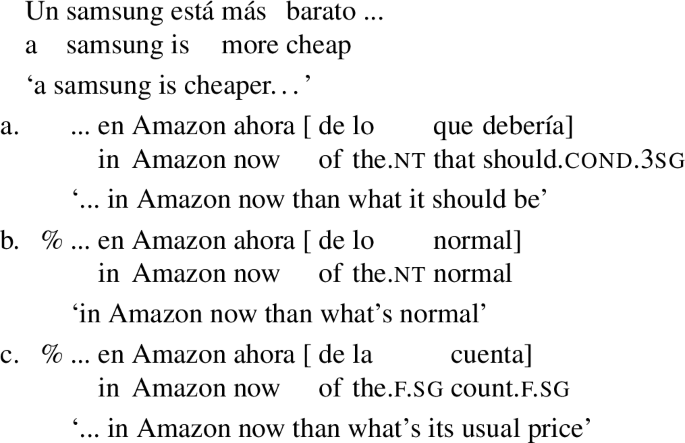

However, this is not entirely accurate and the judgments are more nuanced than what has been originally reported. In particular, there is a split between standards that are ruled out by DEG and those that are not. In other words, no speaker consulted ever accepts the inverse scope when de introduces numerically-modified phrases or degree-denoting pronouns; but some speakers do accept más to scope over modals when the de-standard hosts free relatives.Footnote 12

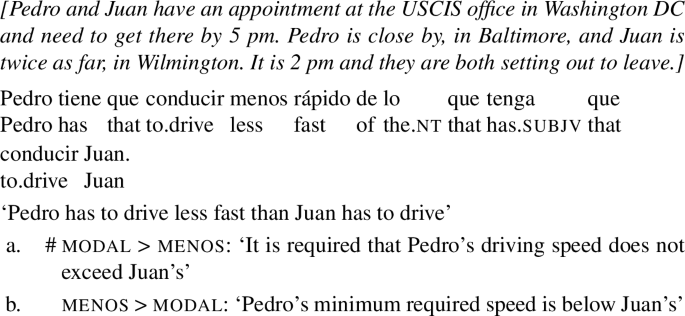

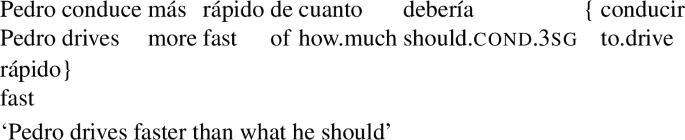

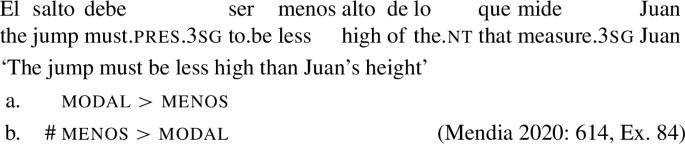

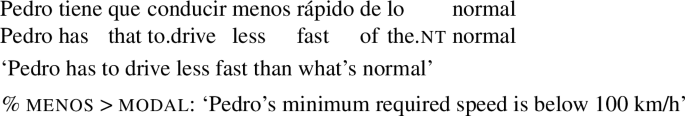

Consider the example in (20) based on Heim’s (2006) driving scenario. The two possible readings are in (a) and (b).

-

(20)

The standard denotes the maximal degree to which Juan has to drive, e.g. 100 km/h. Given the context, the sentence in (20) expresses the intuition that Pedro needs to drive less fast because the distance he has to cover is smaller in the same amount of time. In this scenario, the sentence is false under the interpretation where it is disallowed for Pedro to drive faster than Juan. Crucially, however, the sentence is true under the interpretation that Juan’s driving speed is higher than Pedro’s but it is acceptable for Pedro to drive faster than him; it is just that Juan’s minimum required speed is above Pedro’s. This interpretation is obtained by less taking inverse scope over the modal.

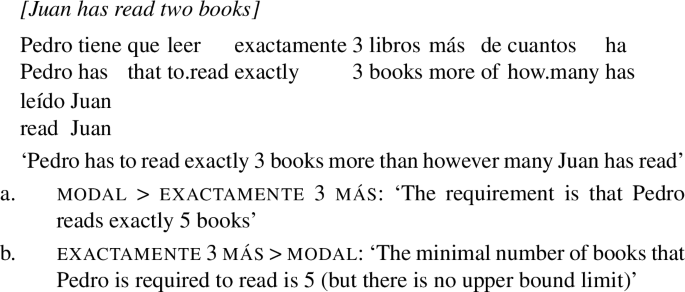

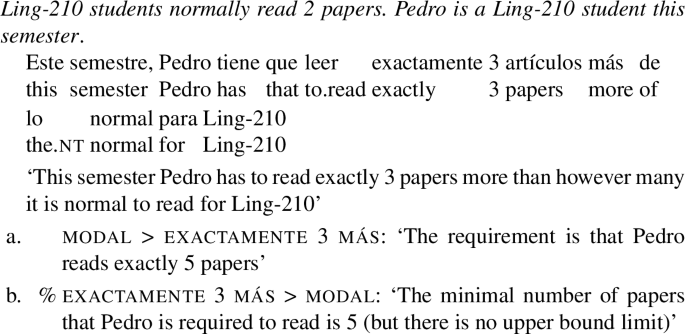

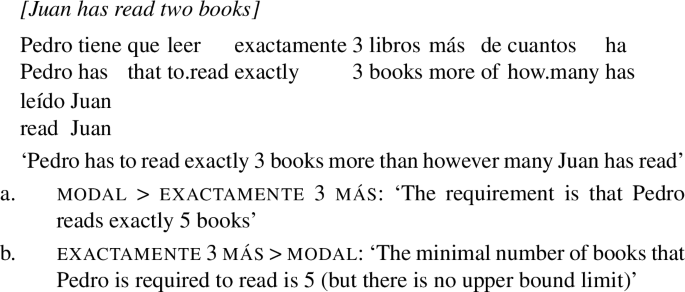

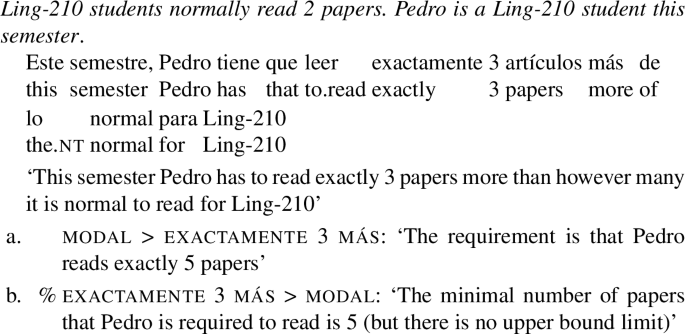

Similar scope facts are obtained with exactly differentials. This is illustrated in (21) which is ambiguous between Pedro having read exactly 5 books and Pedro having read at least 5 books. Both interpretations are acceptable.

-

(21)

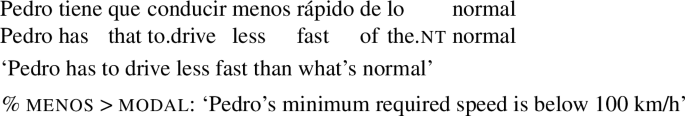

Regarding reduced free relatives such as (15), there is speaker variation as observed for extraposition into the clause and the size of the ellipsis site. In fact, I show in the next section that this variation in the acceptability of inverse scope correlates with the size of the ellipsis antecedent. The relevant data is in (22). We can make use of the same context for (22) as in (20) and assume that lo normal ‘the.nt normal’ = 100 km/h—which is Juan’s maximal speed in (20).Footnote 13

-

(22)

-

(23)

These examples contribute to the claim that the comparative morpheme in de-comparatives can also scope over intensional predicates.

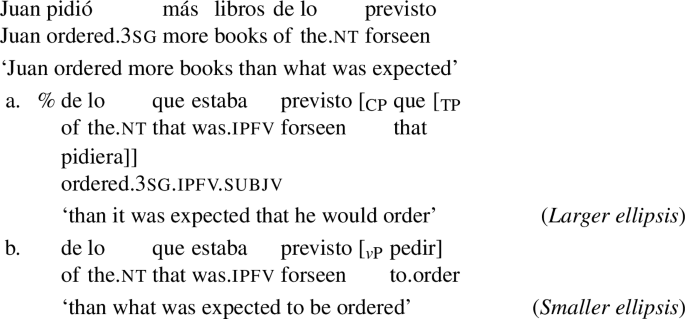

2.2.4 Ellipsis and ACD resolution

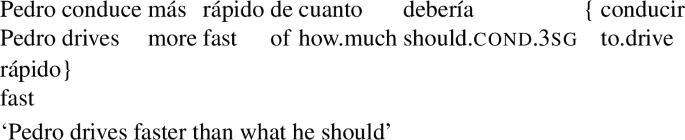

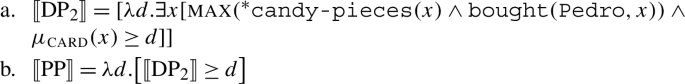

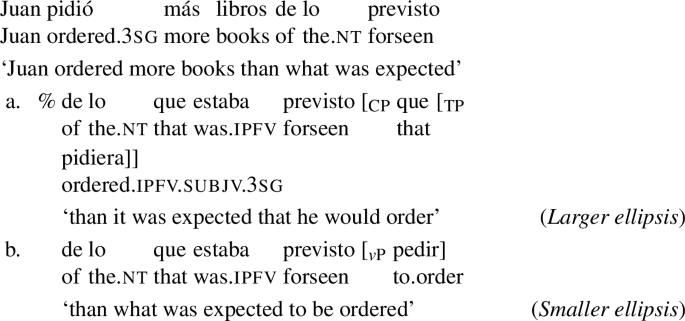

In (12), I introduced the Ellipsis-Scope generalization which correlated the position of the DegP (by means of the standard of comparison) with the resolution of an ellipsis site. The generalization is also active in de-comparatives where the nominals inside the de-standard may also contain an ellipsis site. This is more clearly seen when the complement of de is a free relative as in (24).

-

(24)

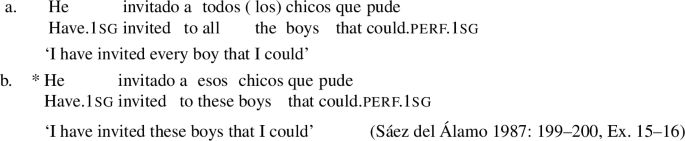

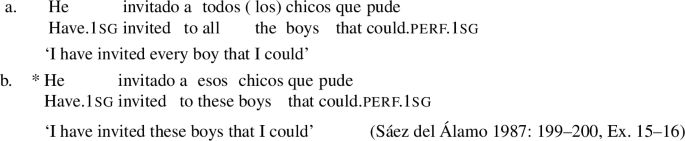

(24) is a special case of ellipsis, namely Antecedent Contained Deletion (ACD) (May 1985) that involves a modal verb or an intensional predicate (Sáez del Álamo 1987).Footnote 14

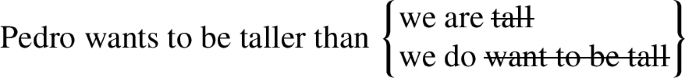

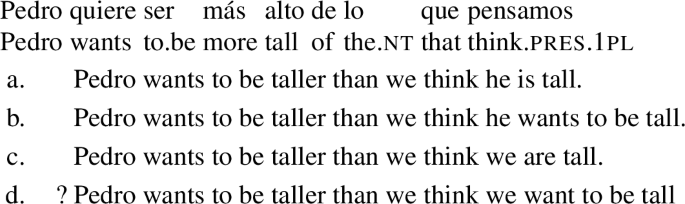

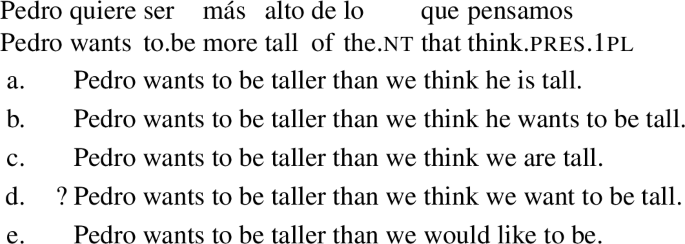

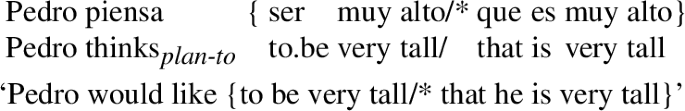

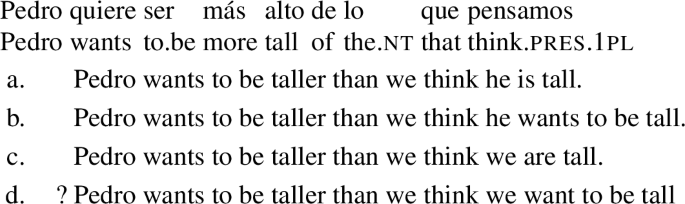

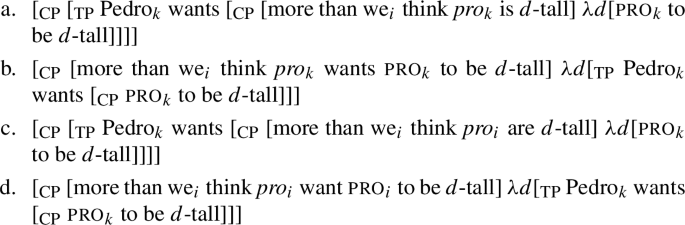

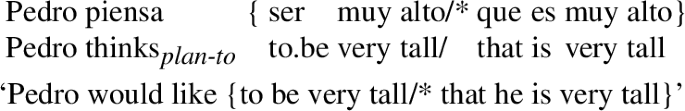

The Ellipsis-Scope generalization cannot be illustrated with a typical English example involving VP-ellipsis like (25), due to the unavailability of VP ellipsis in Spanish (Saab 2007; Ranero 2021). We can test for ACD using verbs that allow for null complements, as in (24). But that might bring the additional complication that some verbs allow for both a finite and a non-finite complement. Of special interest are cases with the verb pensar which is lexically ambiguous between ‘to think’ and ‘to plan to/want to become.’ For example (26) is multiple-ways ambiguous:

-

(25)

-

(26)

The 4 possible interpretations are the result of resolving the ACD site of the verb pensar with the meaning of ‘to think.’ When pensar has this meaning it requires that its clausal complement be finite: the embedded clause in (26a) and (26c), and the matrix clause including the subject in (26b) and (26d).Footnote 15

In addition to the 4-way ambiguity, the verb pensar with the meaning of ‘to plan to/ want to become’ imposes a different selectional requirement on the clausal complement that it embeds: it must be non finite. When this is the case, it induces an additional interpretation.Footnote 16 As a result, this gives rise to a fifth possible interpretation of the sentence in (26).This is illustrated in (27):

-

(27)

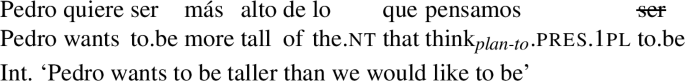

In addition to full free relatives, reduced free relatives also contain an ACD site that needs to be resolved. The size of the ACD site might vary across speakers just like in the case of scopal interactions. For example, in (28), some speakers of Peninsular Spanish accept both a larger and smaller site, whereas others only accept a smaller option.Footnote 17

-

(28)

The consulted speakers all accept to resolve the ellipsis site with a non-finite verb phrase, i.e. vP. For some speakers it is also possible to resolve it by finding a larger antecedent that contains the external argument Juan as well as tense and aspect morphology on the verb, i.e. TP.

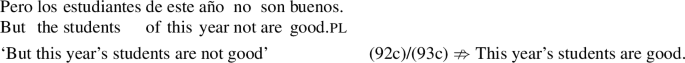

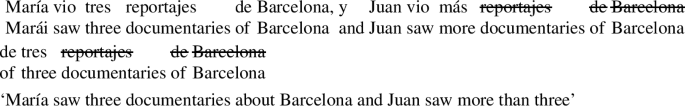

2.3 Interim summary

I have described the major properties of Spanish comparative constructions with que and de standards. I have shown that the properties of más across the two constructions are identical to a large extent: surface extraposition, ellipsis resolution and scope are possible with both types of comparative constructions. These properties are summarized in Table 1 for que and de-comparatives.

Concentrating solely on de-comparatives, however, we have observed that there is some variation depending on the constituent hosted by the standard. According to Table 1, the preliminary generalization that emerges is that there is a major split within de-comparatives: (i) comparative numerals and degree-denoting eso, (ii) and free relatives. On the one hand, comparative numerals and degree-denoting eso do not extrapose into the clause, and neither do they contain ACD sites or allow inverse scope. On the other hand, free relatives do. Additionally, there are fine-grained differences between the class of free relatives across speakers. While full free relatives always allow inverse scope and the ACD site to be large (i.e. at least a TP), reduced free relatives may not. Only if a speaker accepts inverse scope would they also accept a larger ACD site (and viceversa); but if they did not accept the former they would not accept the latter either (and viceversa).

It has been independently argued that extraposition, scope and ACD resolution can be accounted for if the constituent in question is a generalized quantifier (May 1985; Fox 1999, 2000, 2001, 2002; Fox and Nissenbaum 1999; Heim 2001; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Hackl et al. 2012). Thus, it would not be unreasonable to consider más to be quantificational. An appropriate analysis, though, needs to maintain a large degree of syntactic and semantic uniformity for más across constructions, while being flexible enough to capture the variation in Table 1. In the following sections, I argue that this can all be accomplished if más, which always takes the late-merged standard of comparison as its complement, is a generalized quantifier over degrees.

3 Towards a uniform analysis

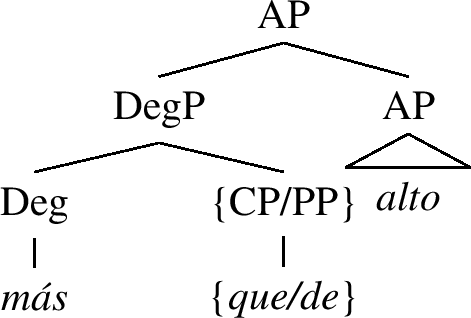

3.1 Spelling out the assumptions

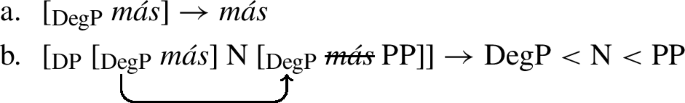

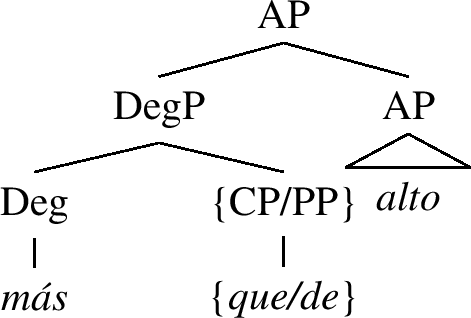

I am adopting the “classical analysis” of comparatives (Bresnan 1973; Hackl 2000; Heim 2001) according to which the comparative morpheme and the standard of comparison form a syntactic constituent to the exclusion of the gradable predicate. Schematically, the syntactic structure under the classical analysis is shown in (29):

-

(29)

Under this view, más is a Degree head that takes the standard as its complement and projects a DegP which is in a specifier position of the phrase it modifies.Footnote 18

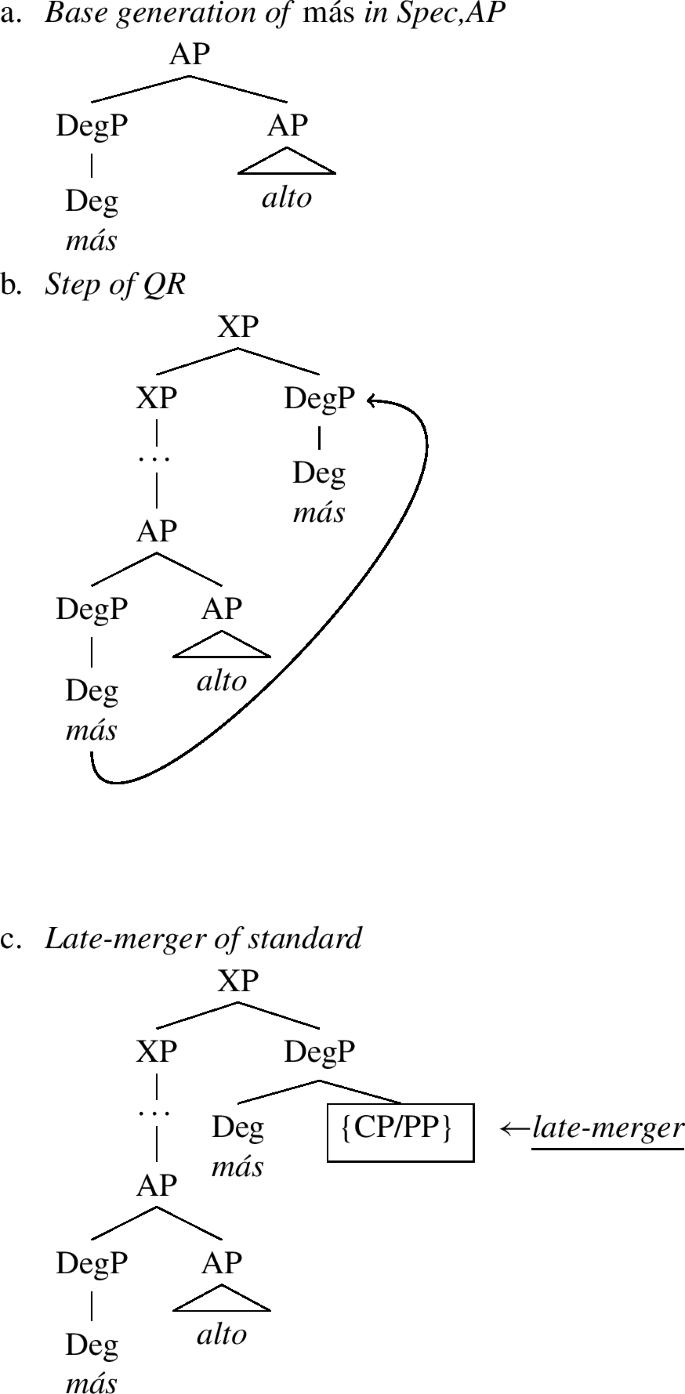

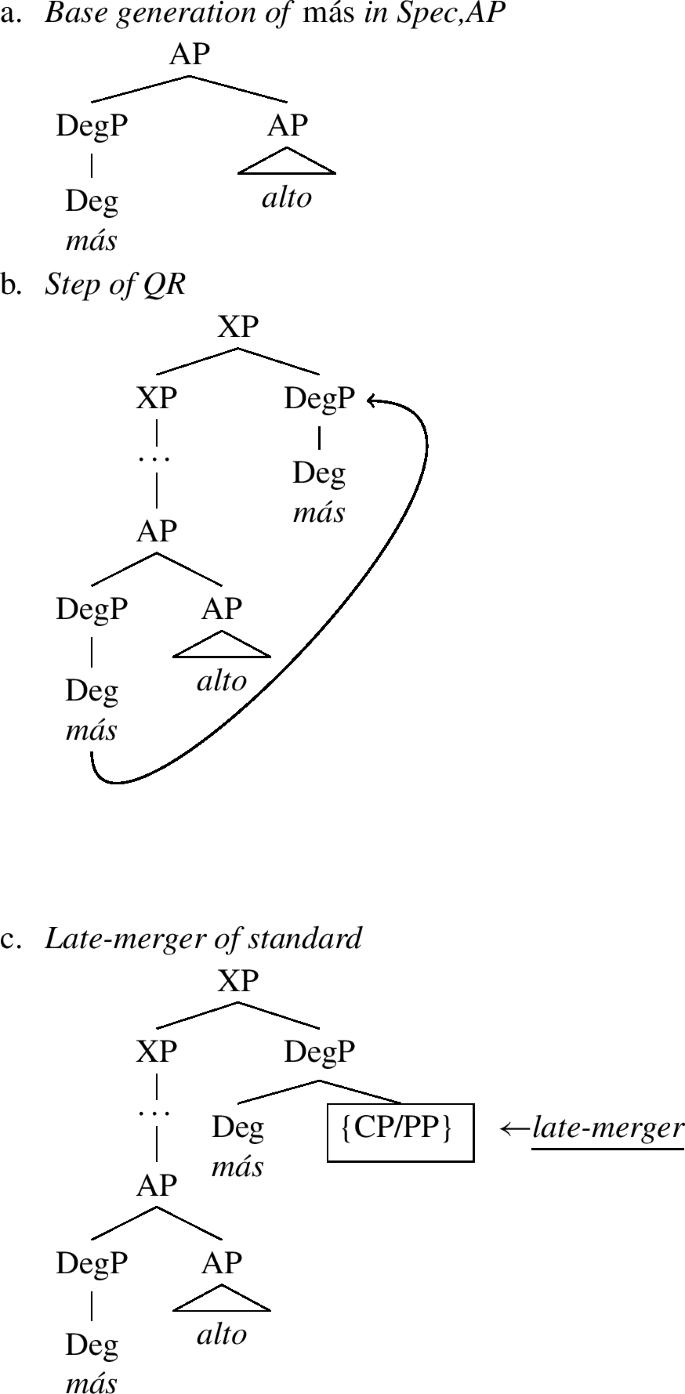

However, I follow the particular implementation proposed by Bhatt and Pancheva (2004): the head-complement relation between the comparative morpheme and the standard is obtained derivationally. Building on Fox and Nissenbaum (1999) and Fox (2000), Bhatt and Pancheva (2004) argue that more/-er undergoes QR and right-adjoins to a scope position; the standard of comparison is late-merged as the complement of the QR-ed comparative morpheme. As a result, the standard of comparison is late-merged in its surface position.

In Sect. 2 we observed that más could take inverse scope over intensional verbs such as modals. According to Heim (2001, 2006) and Bhatt and Pancheva (2004), this is obtained by moving a quantificational element to a position above the modal triggering degree abstraction at the Logical Form (LF) level of representation. Quantifier raising has also been argued to be involved in surface extraposition phenomena (e.g. Fox and Nissenbaum 1999) and ACD resolution (e.g. May 1985; Wilder 1997; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Hackl et al. 2012). That said, a quantificational treatment of Spanish más, on a par with English more/-er, seems empirically appropriate.

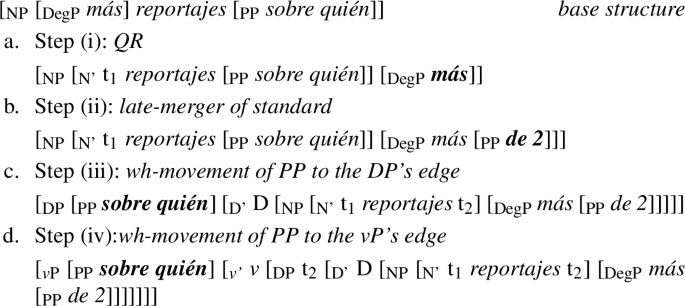

Applied to Spanish, Bhatt and Pancheva’s “classical analysis” entails the following: más will merge in its base position, i.e. the specifier of some phrase; being quantificational, it will then undergo QR leaving behind a copy, and will adjoin to a scope position to the right; the standard of comparison, regardless of whether it is phrasal (i.e. de) or clausal (i.e. que), late-merges as the complement of más in its QR-ed position. Más will then be interpreted in its scope position, but will be spelled-out in its base position. Schematically the steps of the derivation are given in (30):

-

(30)

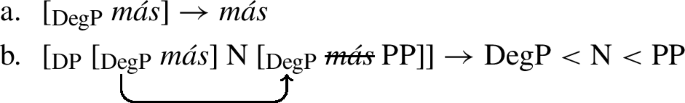

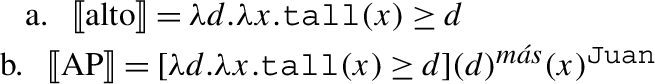

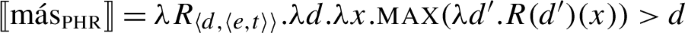

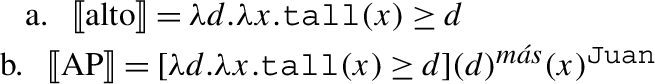

In terms of the semantics, I propose that más is a generalized quantifier over degrees of type 〈〈dt〉,〈dt,t〉〉 across the board. This is the only meaning for the comparative morpheme and its denotation is given in (31), taken from Heim (2001). Additionally, I propose that the standard morpheme is not vacuous and que has the denotation in (32).

-

(31)

\([\!\![\text{m\'{a}s} ]\!\!]=\lambda P_{\langle dt\rangle}.\lambda Q_{\langle dt\rangle}.[\textsc{max}(Q) > \textsc{max}(P)]\)

-

(32)

\([\!\![\text{que}_{\textsc{deg}} ]\!\!]= \lambda D_{\langle dt\rangle}.\lambda d. [\textsc{max}(D) \geq d]\)

Following Pancheva’s (2006) analysis of comparative and standard markers in Slavic languages, where we also observe a clausal vs. phrasal distinction, I treat que along the lines of a pseudo-partitive preposition: que will take a set of degrees as its first argument, and will return another set of degrees.Footnote 19

Más takes two arguments which are sets of degrees: the late-merged standard and the constituent in its scope after QR. I am assuming, following Heim and Kratzer (1998), that, after QR, más leaves a variable of type d in its base position. The variable is bound by a λ-abstractor created as a result of movement of más. The same operation of degree-abstraction holds in the clause inside the standard (Heim 2001).

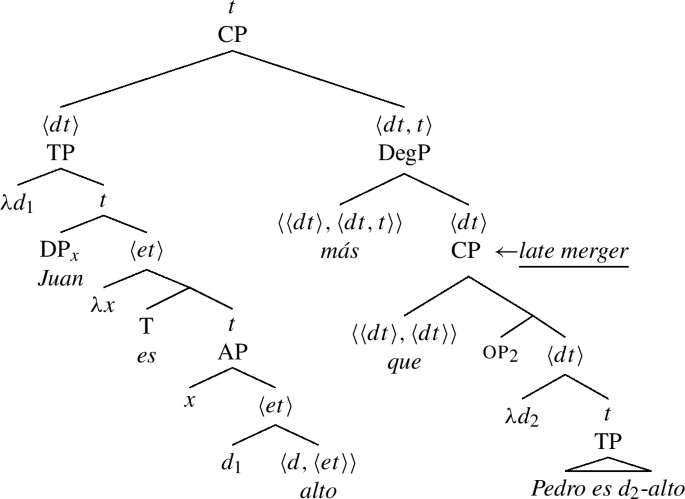

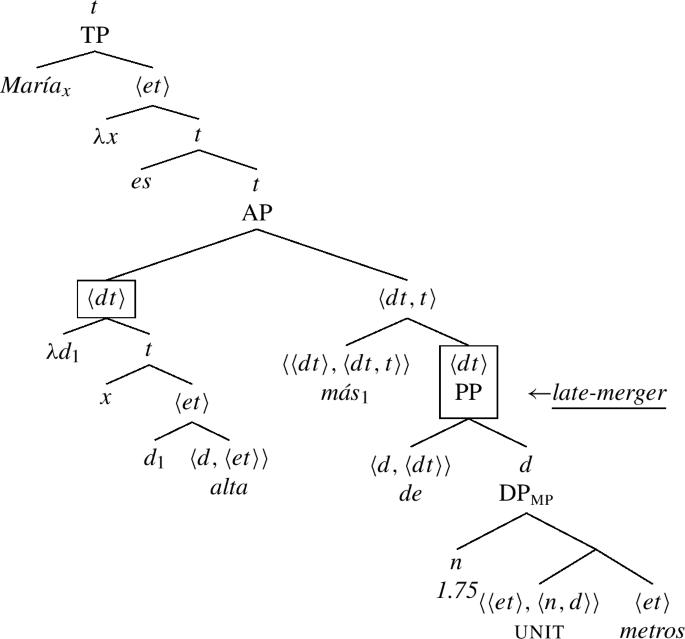

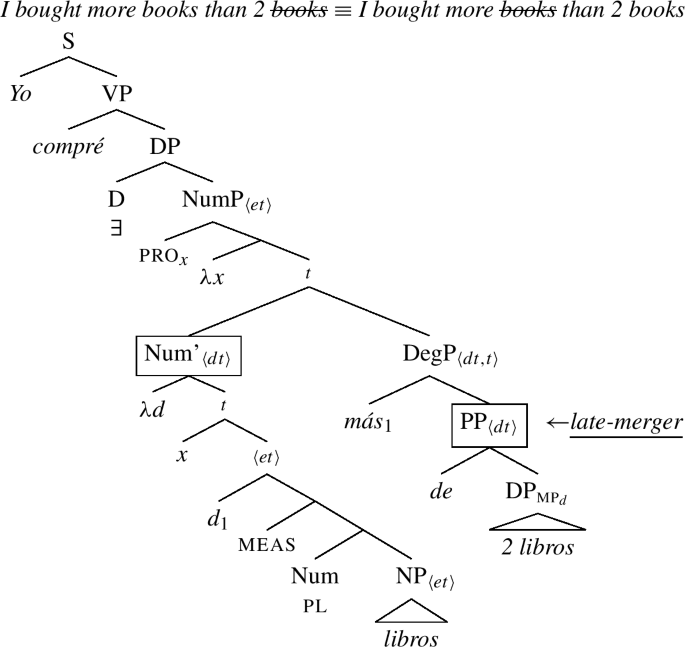

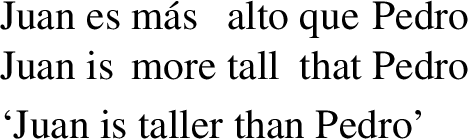

The tree in (34) illustrates the derivation of the sentence in (33) where más has QR-ed and adjoined to the right. I assume that the copula in T is an identity function.

-

(33)

-

(34)

As the structure in (34) shows, más undergoes QR to a higher node (i.e. the matrix TP), which is of type t leaving behind a trace of type d in the base position. The gradable adjective alto ‘tall’ then takes the degree variable as an argument.Footnote 20 QR of más creates a λ-abstractor which binds the degree variable inside the AP and composes with its sister node of type t via Predicate Abstraction (Heim and Kratzer 1998). Predicate Abstraction returns a set of degrees of type 〈dt〉 which serves as the second argument for más.

Que-comparatives will follow this same pattern regardless of the syntactic category being compared (i.e. NP, AP, VP etc.) and the remnant inside the standard. We can thus generalize the derivation in (34) to every case of canonical clausal comparatives. The only difference will be that the longer the QR, the higher in the structure the standard of comparison will be late-merged. As a result, the surface position of the que-clause marks the exact scope of más capturing, among other things, the Ellipsis-Scope Generalization in (12).

The real challenge to the uniform analysis of comparatives is presented by the variation observed in de-comparatives. While—as shown in the introduction and argued by Mendia (2020)—the constituent inside the standard denotes a degree rather than a set of degrees, according to DEG in (17) and Table 1, standards containing numerals and degree-denoting pronouns have different properties than free relatives.

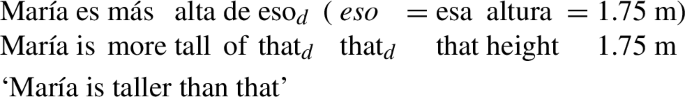

In order to make any headway in our understanding of these constructions, we must first analyze the underlying syntactic structure of these comparative numerals. In the next subsection, I focus on them. I propose an analysis of comparative numerals along the lines of Bhatt and Homer’s (2019) analysis of differential comparatives. This has the welcome result of unifying differential MP constructions and numerically modified NPs within de-standards. In addition, the arguments and data in the next section will allow us to understand the facts captured by the DEG in (17), and will add a motivation for local QR: NP-ellipsis resolution.

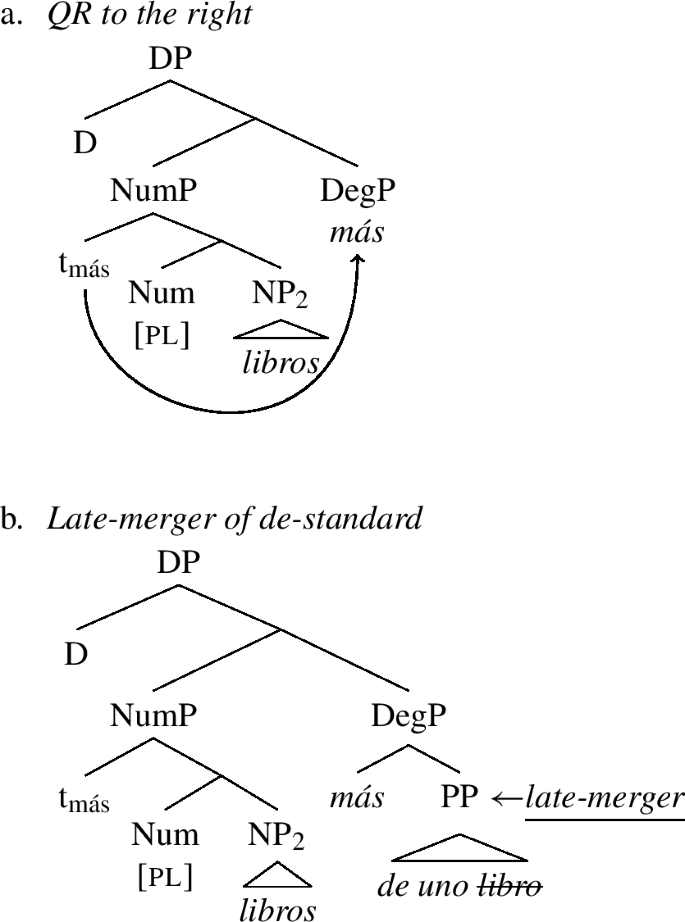

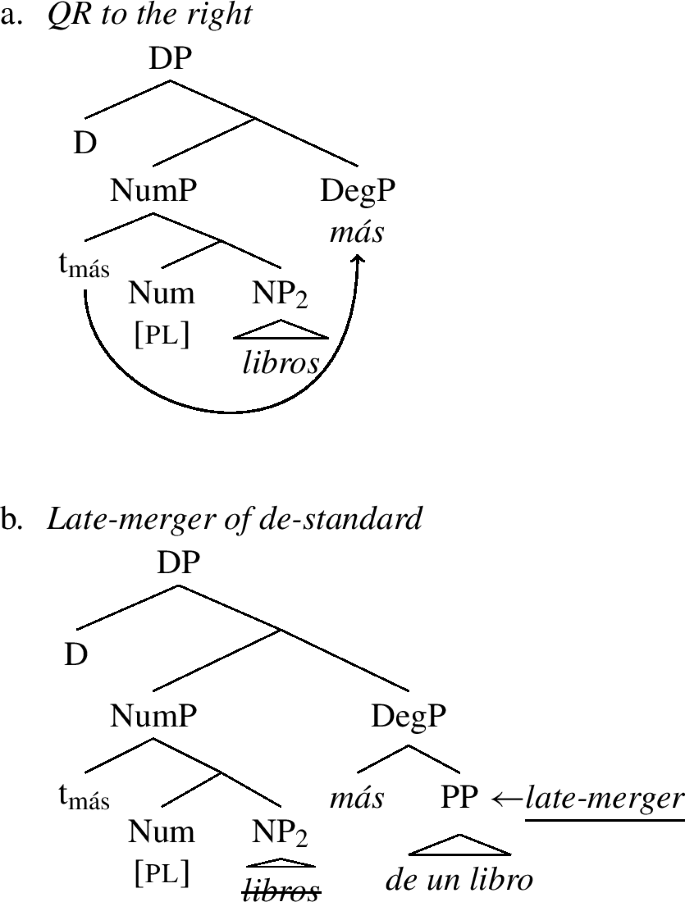

3.2 The syntax of comparative numerals

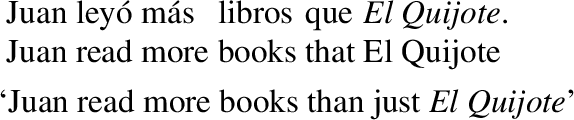

Comparative numerals like (13), repeated below as in (35), pose some challenges to the QR analysis of comparatives. As I noted, the sentences are truth-conditionally equivalent. And yet, the word orders differ: más and the standard are not (linearly) separated from each other in (35a) while they are on the surface in (35b). This is specially puzzling under a QR analysis because (i) the high copy of más that is a sister to the standard is generally deleted, and (ii) the standard cannot appear extraposed into the clause.

-

(35)

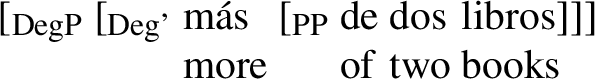

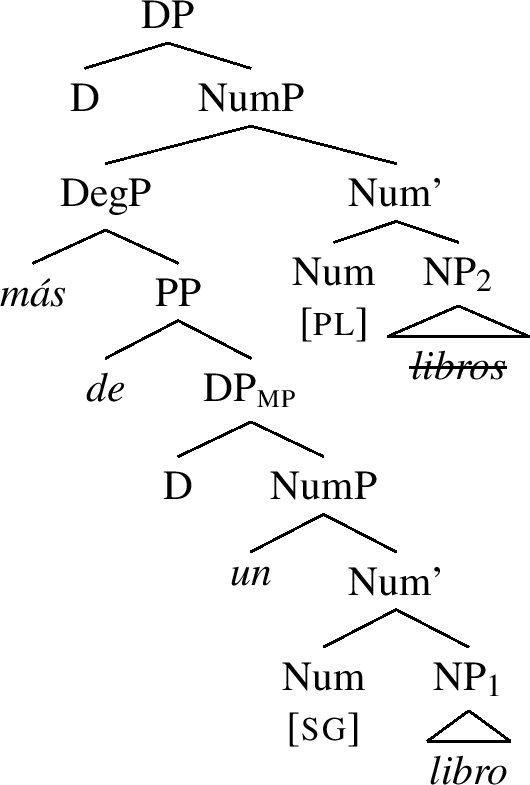

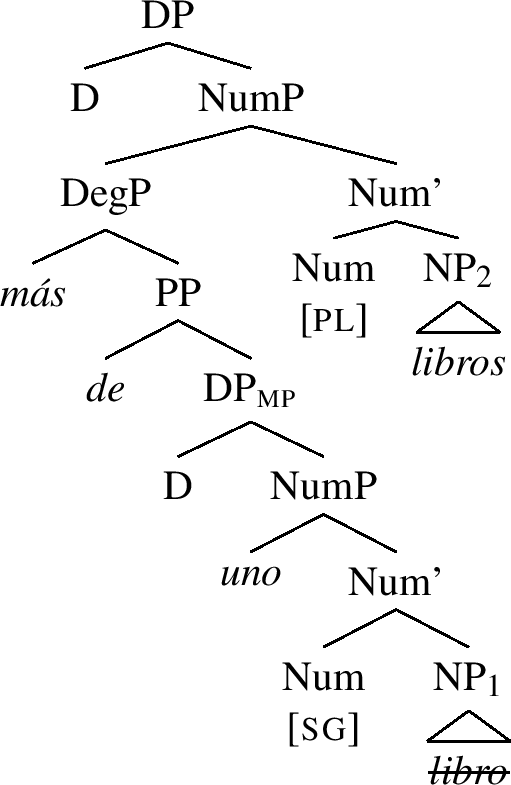

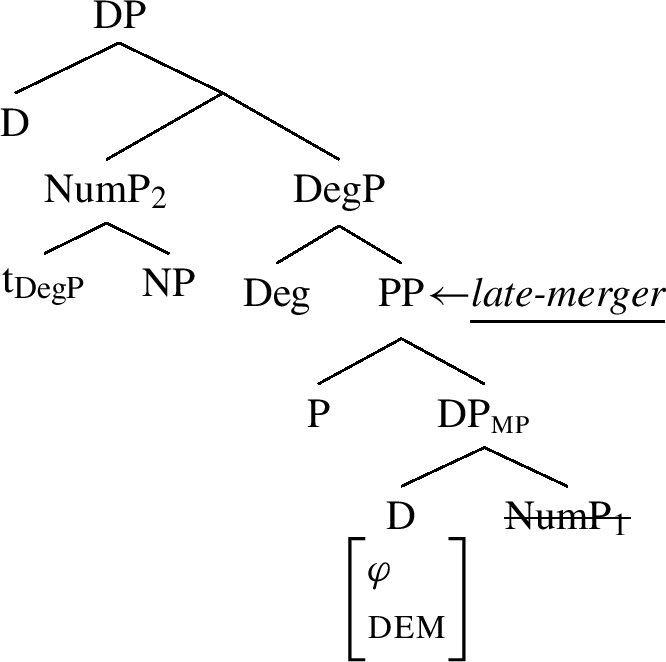

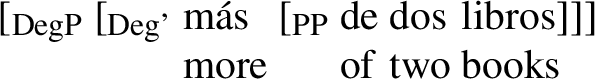

Based on cross-linguistic data from comparative numerals, Arregi (2013) argues that the degree head and the standard of comparison must form a constituent. Arregi, who is not concerned with issues of QR and extraposition of the standard, captures that dependency with the structure in (36):

-

(36)

I take Arregi’s (2013) insights about the relationship between más and de to be correct. Building on Arregi (2013) though, I propose that comparative numerals like (35) consist of two identical NPs: one inside the standard and another outside of it. The former is the one directly modified by the numeral, and the latter is part of the extended projection of the matrix DP. Either NP may or may not be overt. The finer-grained structure of comparative numerals is schematically represented in (37), ignoring extraposition for the moment, where the DegP occupies a specifier position in the extended projection of the standard-external NP:

-

(37)

[NumP [DegP [Deg’ más [PP de [DP # Num NP1]]]] [Num’ Num NP2]]

A crucial consequence of this structure, which was already anticipated in (36), is that the complement of de cannot be the numeral alone, it must be the numeral and the noun it modifies. In what follows, I provide empirical motivations for the structure in (37).

3.2.1 Motivating the syntax

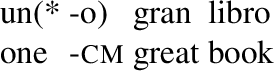

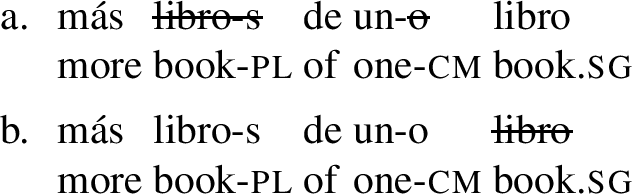

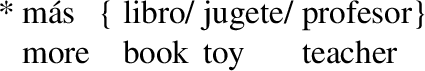

Class marker deletion & number mismatches under ellipsis in Spanish.

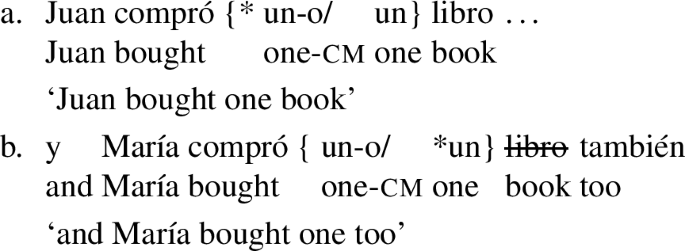

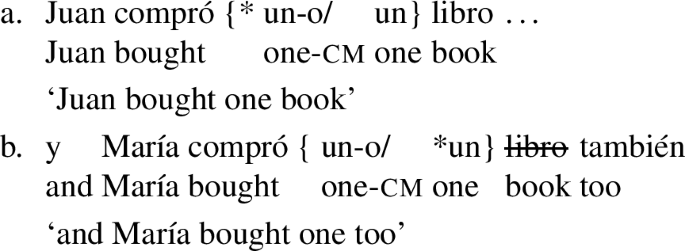

Arregi (2013) observes that the class marker (cm) of the numeral uno ‘one,’ i.e. the vowel -o, is deleted when the numeral is in a local relationship with the noun being modified.Footnote 21 However, the class marker is retained if the NP is deleted. This contrast is given in (38):

-

(38)

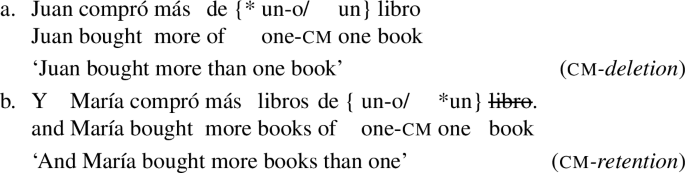

If comparative numerals involve NP-ellipsis, we should expect the same patterns of class marker-deletion/retention. This is borne out as shown in (39):

-

(39)

When the NP directly modified by the numeral inside the standard is overt, the class marker on the numeral is deleted. However, if only the standard-external NP is overt, the class marker is retained.

In addition to class marker deletion, Spanish allows the antecedent NP and the elided NP to mismatch in number (Picallo 2008; Lipták and Saab 2014). This is shown in (40) from Lipták and Saab (2014: p. 9) where the antecedent NP libros in the first conjunct is plural but the elided NP in the second conjunct is singular.

-

(40)

If the comparative numeral constructions under discussion involve NP-ellipsis, the same mismatches between standard-internal and standard-external NPs are expected. That is precisely the case of (39). The NP can be overt or deleted in either position (i.e. standard-internally or externally) without having a truth-conditional impact. In (39a) it is the standard-external NP that has been deleted and so is the class marker of uno, due to the numeral and the singular NP being in a local relationship. The standard-internal NP is overt and singular. In (39b), on the other hand, ellipsis has targeted the standard-internal NP: the numeral uno requires the NP it modifies to be singular. As a result of this NP being deleted, the class marker on the numeral is retained. In short, the sentences in (39) are underlyingly as in (41):Footnote 22

-

(41)

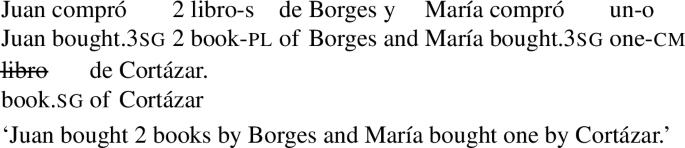

Furthermore, there is independent evidence from the countability restrictions imposed by degree morphemes that the singular libro, in (39a)/(41a), cannot be standard-external: it must form a constituent with the numeral un. Comparative morphemes and vague numerals (e.g English many, Spanish muchos/tantos) are incompatible with singular count NPs, but are compatible with plural count or mass NPs (Krifka 1989; Chierchia 1998; Hackl 2000; Schwarzschild 2006; Nakanishi 2007; a.o.).Footnote 23 Thus, if más was modifying the singular count NP, the sentence must be ungrammatical. Since it is not, and considering that number mismatches are allowed between antecedent and elided NP, más must be modifying a different NP, namely a plural count NP: libros. This rules out a bracketing like the one in (42):

-

(42)

Additional evidence: Number and class agreement in Bulgarian.

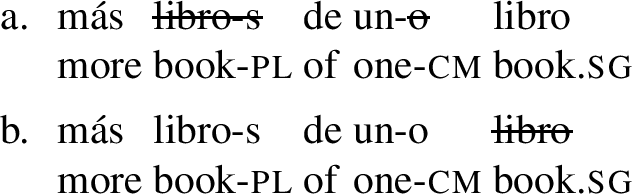

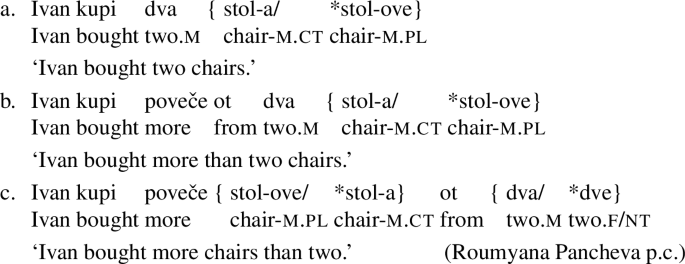

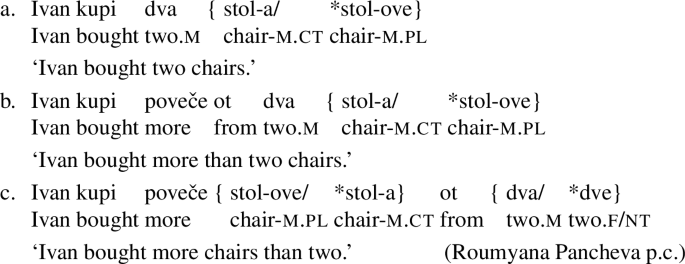

This is not an isolated accident from Spanish. In fact, similar facts obtain in Bulgarian. In Bulgarian the numeral ‘two’ inflects for gender: masculine dva vs. feminine/neuter dve. Masculine inanimate nouns have to appear in the “count” form (i.e. ct) with numerals, not the plural. The “count” morpheme is an adnumerative form, distinct from singular and plural (Ionin and Matushansky 2018: 199–204).Footnote 24 However, masculine inanimate nouns cannot appear in the “count” form with vague numeral ‘many’ and comparative poveče ‘more’; they have to appear in the plural form. This is shown in (43):

-

(43)

In the simple numeral construction in (43a), the noun ‘chair’ is masculine count, e.g. -a. The same is observed in the comparative numeral in (43b). This indicates that dva ‘two’ and the noun stol-a ‘chair-m.ct’ are in a local relationship. The agreement pattern changes when the comparative poveče stands in a local relationship with the noun ‘chair’ in (43c): ‘chair’ is masculine plural, e.g. -ove, instead of masculine count, e.g.-a. Importantly, in the Bulgarian counterpart of ‘more chairs than 2’ in (43c), the numeral is obligatorily masculine.

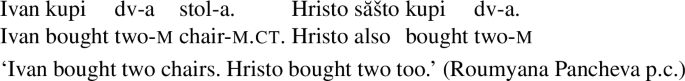

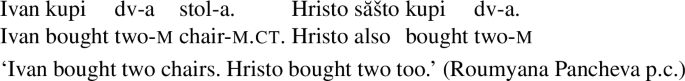

From (43c) we can conclude several things. First, there is an NP that is external to the DegP (NP2 in (37)) and is directly modified by the comparative morpheme. This is evidenced by the masculine plural agreement. Second, just like in (43b), the numeral ‘two’ surfaces with the masculine form, suggesting that there is an elided NP stol-a ‘chair-m.ct’ inside the standard that the numeral agrees with. The fact that there is NP ellipsis in the standard is independently supported by nominal ellipsis under a numeral. This is illustrated in (44).

-

(44)

The numeral ‘two’ retains the same masculine morpheme, e.g. -a, when the NP ‘chair’ has been deleted in the second sentence. In short, Bulgarian comparative numerals behave like Spanish.

Despite the fact that in no language, as far as we know, do we see the pattern more books than 2 books overtly where the NP books is repeated, there is evidence that there are actually two instances of the same NP: cm-deletion and number mismatches in Spanish, and count gender agreement in Bulgarian adnominative numerals. As a result, I propose that underlyingly there are two identical NPs, one inside the standard of comparison and another external to the DegP: either NP may then undergo deletion. Again ignoring extraposition for the moment, I propose that comparative numeral constructions have the syntax in (45)—for Spanish (39a) and Bulgarian (43b)—and in (46)—for Spanish (39b) and Bulgarian (43c):

-

(45)

more than one book

-

(46)

more books than one

The structures capture the numeral agreement patterns and class maker syncope described above. Furthermore, an advantage of these structures is that the dimension of comparison is kept constant (e.g. cardinality of books), and need not be stipulated.Footnote 25

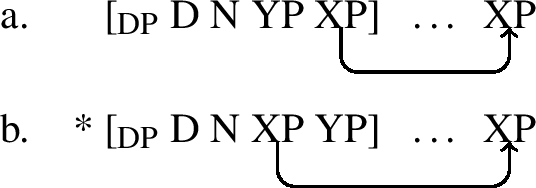

3.2.2 Deriving the word order patterns

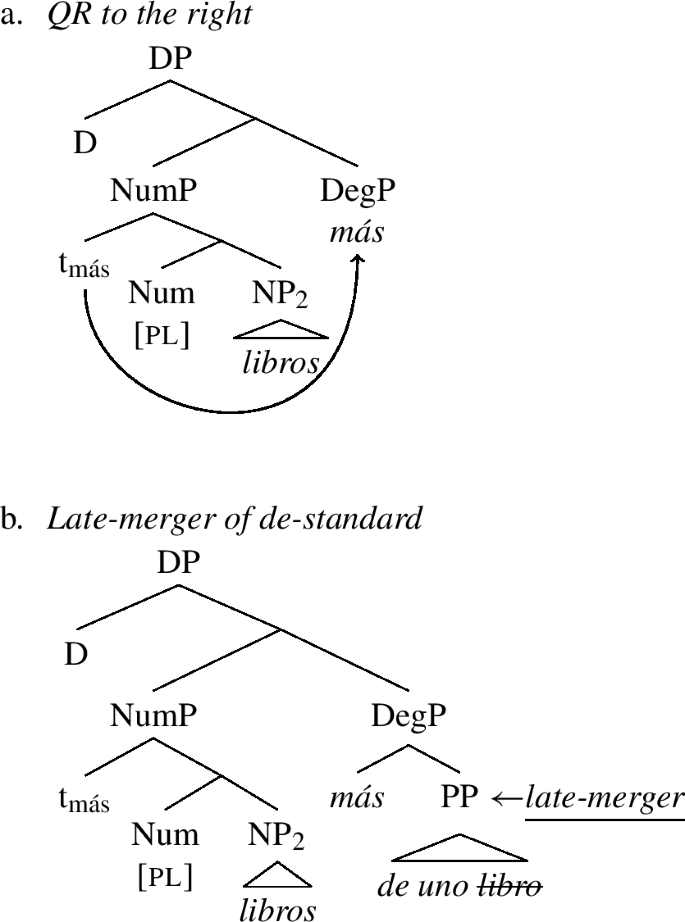

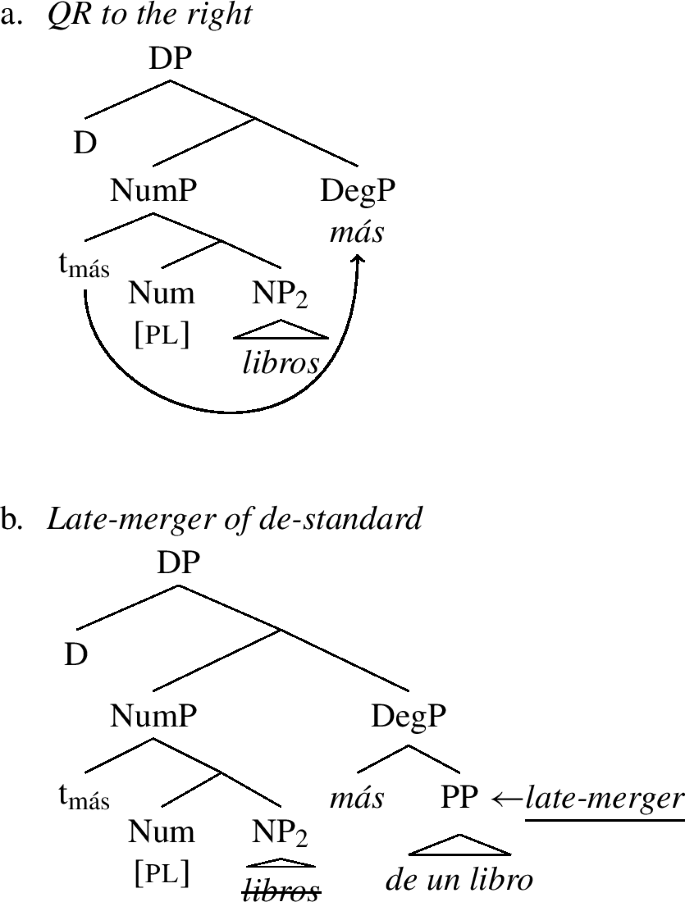

The structures proposed above for comparative numerals, and in particular (46), look like a prima facie challenge to the surface word order observed for comparatives. If the structures were to remain as they are in (45) and (46), the DegP should be linearized to the left of NP2 libros; but this is not accurate because the standard of comparison does never surface in that position. This challenge is only apparent given that I am adopting Bhatt and Pancheva’s (2004) analysis of comparatives according to which más undergoes QR to the right (Fox and Nissenbaum 1999; Fox 2000). It is in this position where the standard of comparison is late-merged. This is illustrated in (47) for the structure in (46) where intermediate projections have been omitted for simplicity:

-

(47)

Under the Copy Theory of Movement (Chomsky 1995, Nunes 1995, et seq.), movement of más leaves a copy in its base position, i.e. Spec,NumP. The movement and late-merger of the standard take place before the structure is spelled-out and transferred to PF and LF. Once the structure is spelled-out, at PF there are two copies of the moved quantifier. Given the Phonological theory of QR (Bobaljik 1995b, 2002; Pesetsky 2000), the highest copy created via movement is deleted and the lowest one in Spec,NumP is spelled-out. There is only one copy of the standard of comparison, though, since it has been late-merged in the DegP’s final landing site. Furthermore, given the step of rightward QR, the standard will be linearized to the right of everything it c-commands (Nunes 1995, 2004; Uriagereka 1999; Fox and Pesetsky 2009; Davis 2023; a.o.).

The semantics that I assume for más in (31) (a generalized quantifier over degrees) forces it to QR to a scope position. This DP-internal scope position has been independently argued for in the domain of comparatives (Matushansky 2002) and superlatives (Heim 1999; Sharvit and Stateva 2002; Pancheva and Tomaszewicz 2012). The quantifier composes with the late-merged standard in this position. In addition to resolving the type mismatch, QR to the DP internal position feeds NP ellipsis resolution.

These same operations occur when the DegP external NP is elided instead. As shown in (48), más QR-s to the right leaving a copy in its base position; the standard is then late-merged in the final landing site of más. Despite the fact that surface order invites an analysis in which the standard of comparison is merged (and subsequently interpreted) in the base position of más, the syntactic and semantic evidence tells us otherwise.Footnote 26

-

(48)

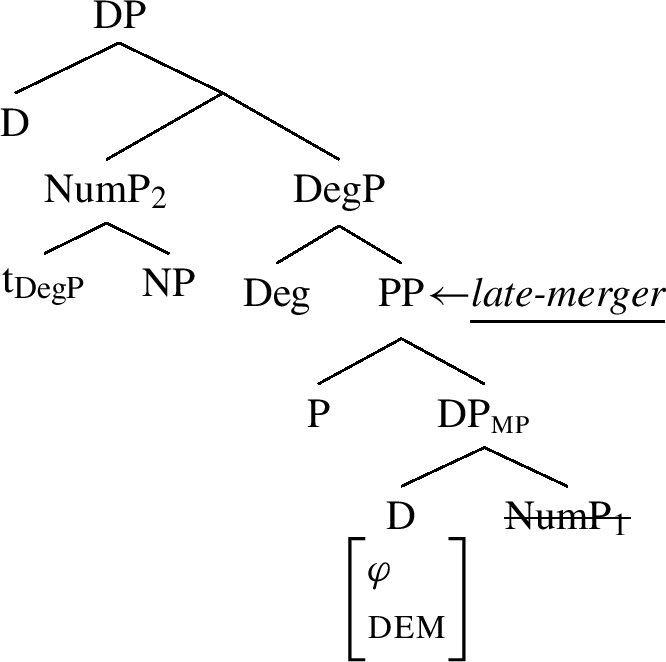

3.2.3 Extending the analysis to de-standards with degree-denoting pronouns

De-standards containing degree-denoting pronouns are no different from the comparative numerals just discussed. Pronouns have been argued to be definite determiners whose complement has undergone ellipsis (Postal 1966; Elbourne 2001, 2005). Thus, despite the fact that there is a single exponent eso, pronominal de-standards have the syntax of a full DP whose D head has survived deletion. Thus, at LF that covert piece of structure must be interpreted. In other words, the underlying syntax of numerically modified NP standards and pronominal ones is identical, but the sentences differ with respect to their externalization at PF.

According to Elbourne (2001), there are two conditions that make the NP/NumP deletion rule possible: an overt linguistic antecedent, or the presence of deictic aid in the discourse. In a sentence like (49), it is the first condition that is met, whereas in (50) it is the second condition that is met:Footnote 27

-

(49)

-

(50)

[Juan is 1.75 m tall]

The underlying structures for (49) and (50) are given in the trees in (51) and (52) respectively, where the PP has also been late-merged:

-

(51)

Structure of (49)

-

(52)

Structure of (50)

This has the desired result: at LF, the degree quantifier is adjoined to node of type t and the conditions for interpretation (in terms of cardinality or quantity) are met. At PF, D’s complement is deleted and rules of impoverishment taking place before Vocabulary Insertion (Arregi and Nevins 2012; Haugen and Siddiqi 2016) make sure that the correct exponent is inserted under the D node inside the standard.

3.2.4 Tacking stock

The underlying syntactic structure I have proposed does not only receive cross-linguistic empirical support, but it is also parsimonious. In both que and de-comparative, QR takes place. We achieve a parallelism between de-comparatives and que-comparatives with respect to QR. In addition to this, this structure has two extra benefits. First, we are able to explain Mendia’s (2020) observation that the dimension for comparison needs to be kept constant. This follows from the fact that the standard-external and standard-internal NPs are identical: if the NP is books, for example, we are comparing the degree of cardinality that n-books have to the degree of cardinality that n’-books have.

Second, we can draw a parallelism between differential Measure Phrase (MP) constructions and the complements of de-standards. As discussed by Bhatt and Homer (2019) and Homer and Bhatt (2020), differential nominal comparatives like 2 books more and 2 more books involve the presence of two NPs: the differential NP, and the NP that introduces the comparative in its specifier. One these NPs has to be covert. As they observe, the two NPs have to be identical for the dimension of measurement to be established along the relevant scale. This is exactly the situation we find in the nominal comparatives under discussion. Furthermore, the same numerically modified NPs that serve as complements of the de-standard can occur as differential arguments as well. This is shown in (53) where we can observe the same class marker deletion patterns as in (39).

-

(53)

Numerically modified NPs selected by de denote degrees, and so do the differentials (von Stechow 1984). Therefore, we can also extend Bhatt and Homer’s (2019) and Homer and Bhatt’s (2020) observation that nominal MPs are coextensive with the class of count nouns.

Considering the discussion in this section, we can now enlarge the generalization for de-comparatives in Table 1 as in Table 2. In fact, we can now take take these properties to diagnose the height and motivation of QR. QR with comparative numerals and degree-denoting pronouns has to occur locally because it is only driven by a type mismatch or by NP ellipsis.

In the next section, I provide a semantics for de. This semantics will allow más to take the late-merged standard of comparison as its first argument, after más has undergone QR.

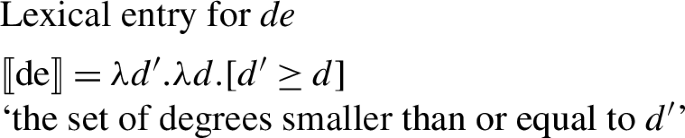

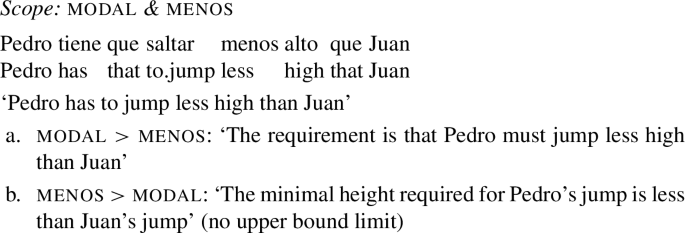

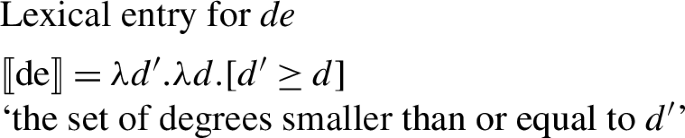

3.3 A semantic role for de

We have observed how the lexical entry for más in (31) appropriately computes the meaning for clausal comparatives: the CP is of type 〈dt〉 as a result of operator movement in the syntax triggering degree abstraction at LF inside the standard. However, as is, más would fail to compose with phrasal comparatives. As I have shown following Mendia (2020), the semantic type of de’s complement is d, i.e. a degree. Thus, there is a type mismatch: más requires its first argument to be a set of degrees, but the standard of comparison denotes a degree.

I propose that we can solve this compositional issue if the preposition de itself is not semantically vacuous (von Stechow 1984; Rullmann 1995; Pancheva 2006; Alrenga et al. 2012). Instead de will take the standard of type d as its argument and return an element of the appropriate type to saturate the comparative morpheme’s first argument. The lexical entry for the preposition is given in (54):Footnote 28

-

(54)

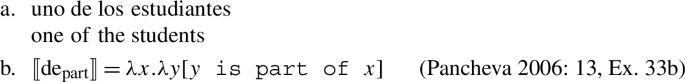

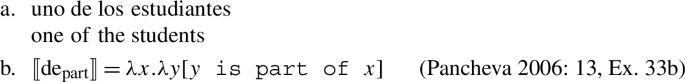

De in (54) denotes a function from degrees d to sets of degrees 〈dt〉. What is more, the lexical entry in (54) reminds us of the meaning of the partitive preposition de in (55): it takes a definite description of a plural or mass individual \(x'\) (of type e), and returns a set of individuals (of type 〈et〉) who are part of \(x'\). Thus, this analysis follows Pancheva’s (2006) thesis that (i) there is a parallelism between the domain of degrees and that of individuals, and (ii) the behavior of -er/más and de is parallel to that of a quantifier and its partitive first argument.

-

(55)

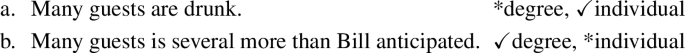

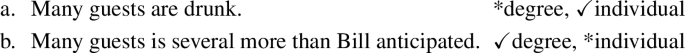

The DP that is de’s complement will saturate de’s first argument. That DP constituent must denote a degree even if its N head is an ordinary sortal noun like libros. It has been observed that numerically modified NPs can be ambiguous between a property-based or a degree-based interpretation (Rett 2014; O’Connor and Biswas 2015; Snyder 2021). These NPs may not themselves be measure-NPs, but ordinary sortal ones like pizza or guest, as in (56) and (57) from Rett (2014). Their interpretation can be disambiguated via agreement: singular agreement generally correlates with the degree interpretation, whereas plural agreement typically correlates with the individual interpretation (Rothstein 2009).

-

(56)

-

(57)

Furthermore, we have already seen that these same sortal NPs can appear as differential arguments where their denotation must be degree-based (von Stechow 1984; Bhatt and Homer 2019; Homer and Bhatt 2020).Footnote 29 That said, I consider that the noun inside the standard must have the semantics similar to that of measure nouns (Krifka 1989; Rothstein 2009, 2017; Scontras 2013; Rett 2014; Ahn and Sauerland 2015). That is, in addition to being a predicate of individuals, the denotation of a noun like book, shirt etc. can be degree-based.

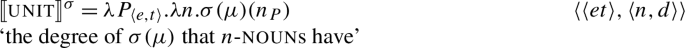

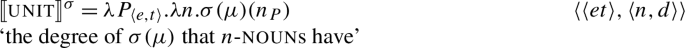

In order to capture this, I follow insights from Brasoveanu (2009), Rett (2014), Homer and Bhatt (2020) and Coppock (2022) and propose that the degree interpretation is derived from the individual-typed interpretation. In particular, I propose that there is a covert operator unit that relates the count NP to the numeral that modifies it. unit introduces a measure function that takes the NP, of type 〈et〉, and the numeral, of type n, and returns a degree of cardinality/volume/weight etc. on the noun-scale that corresponds to n. The denotation for unit is in (58), where σ is any assignment function and σ(μ) is the measure function that σ assigns to μ. The content of the measure function is resolved by what is being measured (cf. Wellwood 2015, 2019):

-

(58)

The degree-based denotation for a noun like libros in 2 libros is in (59). Given that we are measuring plurarlities of books, the value for μ is cardinality (for details, see Wellwood 2019; Cleani and Toquero-Pérez 2022).

-

(59)

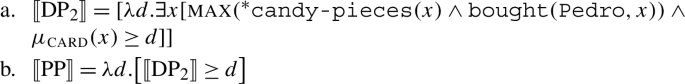

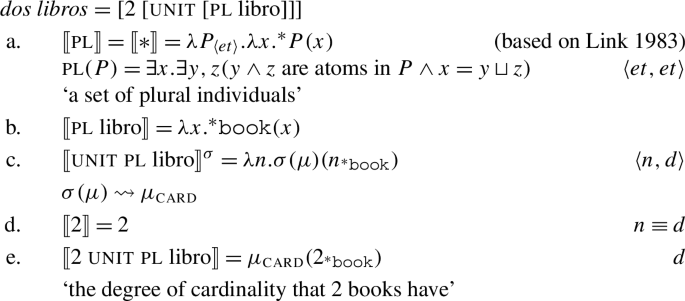

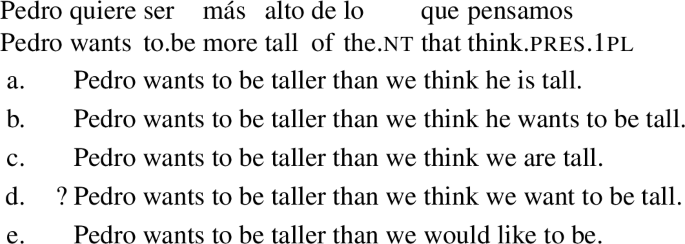

We can now derive the LF and semantic composition of de-comparatives. I do that for the sentence in (50) whose LF I represent in (60). The two arguments of más are boxed.

-

(60)

María is taller than that. [that = 1.75 m]

First más undergoes QR to a scope position and then the de-standard is late-merged. The late-merged PP serves as the first argument of más. Given the underlying syntax advocated for pronominal MPs in (51) and (52), eso is the exponent of a D head at PF, after NP/NumP ellipsis has occurred. At LF the standard of comparison is a fully fleshed DPmp. Semantic composition takes place appropriately given that the PP provides a suitable argument for the comparative morpheme. The derivation of the PP-standard is given in (61).

-

(61)

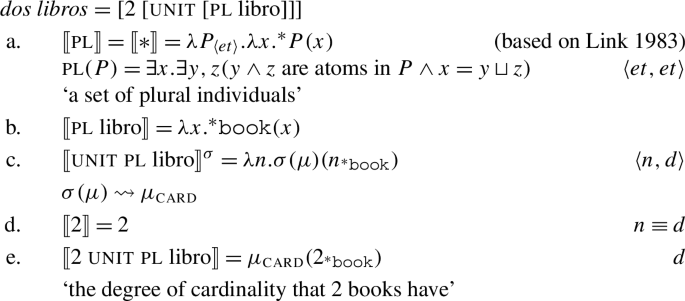

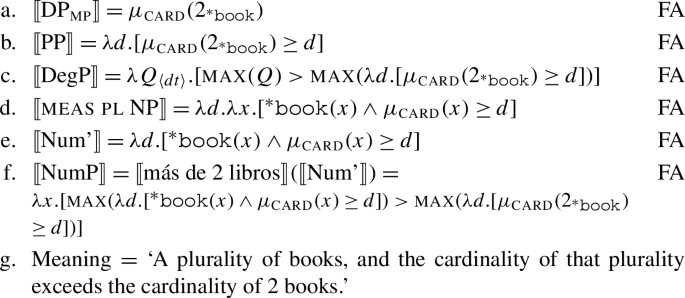

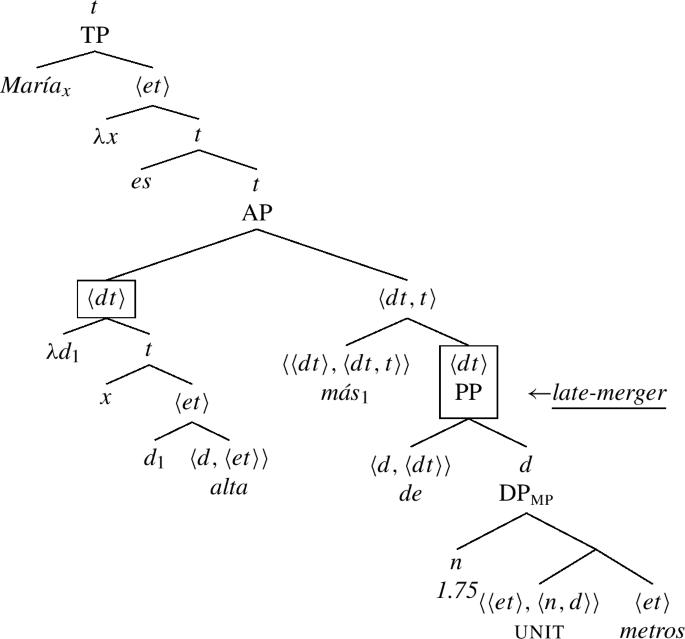

The proposal also makes the right predictions for nominal comparatives such as (35a) and (35b), which are truth conditionally identical and only differ in the location of the NP undergoing ellipsis. Their LF is in (62). The noun libros projects its own NP and the comparative is merged Spec,NumP. Given that QR happens DP-internally, we need a clausal node, of type t for the comparative quantifier to target. Here, I follow May (1985), Heim and Kratzer (1998), Hackl (2000) and Matushansky (2002), and assume that NPs have a subject position (possibly filled with a null vacuous pro) that is abstracted over.Footnote 30 The phonetically empty D has the semantics of a garden variety existential quantifier. The semantic derivation for the quantified NP is provided in (64).

-

(62)

-

(63)

-

(64)

The derivation and computation of the meaning are consistent with the core of the proposal: más is a quantifier, de combines with a DPMP of type d, and there is no QR outside of the DP.

3.4 Free relatives and ACD

I have shown how giving de a semantic value unifies the analysis of más. In this Sect. 1 demonstrate that free relatives (both full and reduced) and resolution of ellipsis inside of them conform to the analysis that I am advocating for.

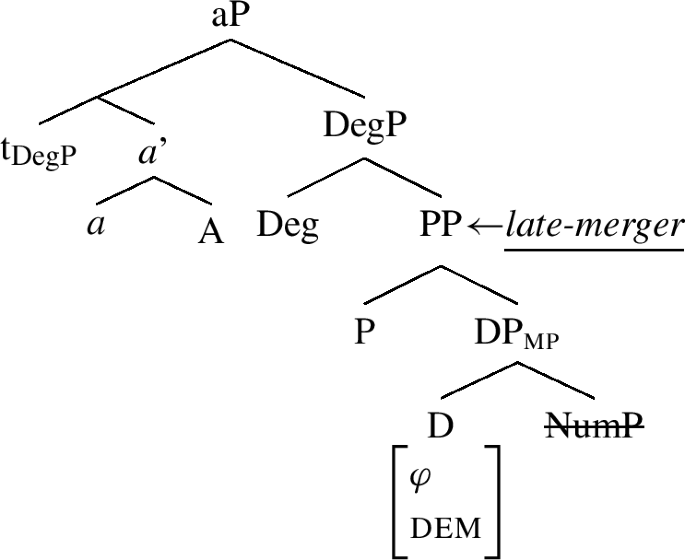

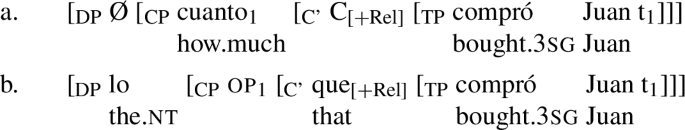

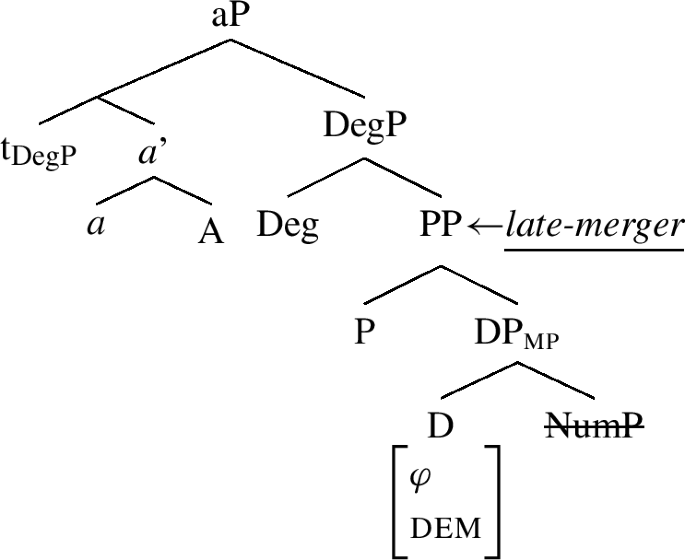

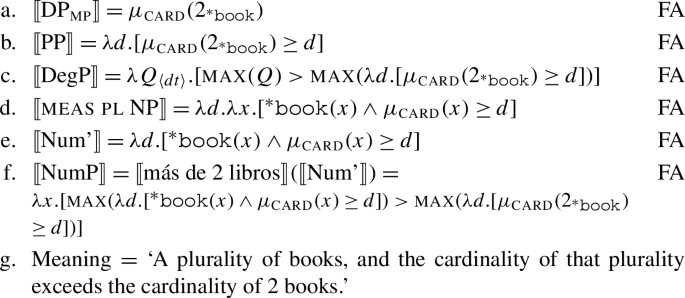

Following Donati (1997), I assume that free relatives involve movement of a wh-operator to the left periphery of CP and then a determiner merges with the CP relabelling the structure as a nominal. This operator movement can be overt as in (65a) or covert as in (65b).

-

(65)

We can assume that the syntactic structure of both (65a) and (65b) is identical with respect to the base position and landing site of the wh-operator: the operator moves to the left periphery of the clause, and binds a variable via lambda-abstraction at LF.Footnote 31 The structures differ regarding the realization of exponents at PF: if the operator is overt (e.g. cuanto ‘how much’) as in (65a), the complementizer is null and so is the determiner that relabels the structure; if the operator is null, the complementizer is spelled out as que and the determiner that embeds the CP is also spelled-out (e.g. lo ‘the.nt’), as in (65b). The determiner in charge of relabelling is also the one that does the maximalization regardless of whether it is overt or not.Footnote 32 The denotation for the maximalizing determiner is provided in (66):

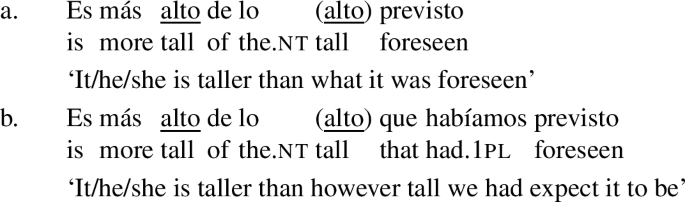

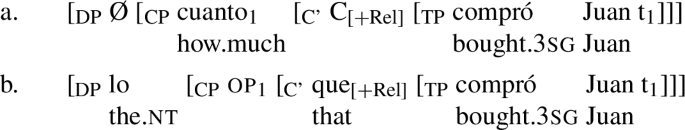

-

(66)

The same is true of reduced free relatives first shown in (15). The only difference is that the operator in charge of the abstraction is null and so is the complementizer. But the D in charge of the maximalization is overt. In fact, it is possible to have an overt gradable predicate inside them which provides evidence for a larger structure and operator movement, as in degree questions. This behavior parallels free relatives as shown in (67) (see also Fábregas 2020: pp. 81–82):

-

(67)

Pied-piping of the adjective is optional, as independently attested in degree questions in Spanish (Gergel 2009, 2010; Eguren 2020). Thus, given the structural parallelism between the two constructions, we should analyze these reduced free relatives on a par with full free relatives in terms of degree abstraction: a degree operator moves to the left periphery and it creates a λ-abstractor that binds the degree variable left after operator movement. This is shown in (68):

-

(68)

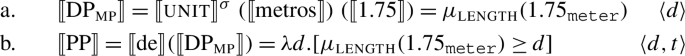

That said, the free relative in (69a) has the LF in (69b), and its corresponding semantic derivation is in (70).Footnote 33

-

(69)

-

(70)

DP2 in (70a) denotes a degree. But this cannot combine with our degree quantifier más because the latter requires a set of degrees 〈dt〉. Thus, the preposition de lifts the type of its complement: a function from degrees to sets of degrees. Más can then compose with (70b) via Function Application.

With this in mind, we can now revisit the cases of ACD within free relatives. A particularly relevant example was (26) repeated below as (71).

-

(71)

When this example was first discussed, I noted that the verb pensar was lexically ambiguous between ‘to think’ and ‘plan to/want to become’ which led to different selectional restrictions on the clause it embeds: the former requires a finite CP, while the latter requires a non-finite clause. Both types of pensar, however, enable an ACD site inside the standard. One way to resolve ACD is via QR (May 1985; Fox 2002; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Hackl et al. 2012). The analysis of más as a generalized quantifier over degrees allows us to adopt this solution. QR needs to target a node that is high enough to remove the ellipsis site from the c-command domain of the antecedent.

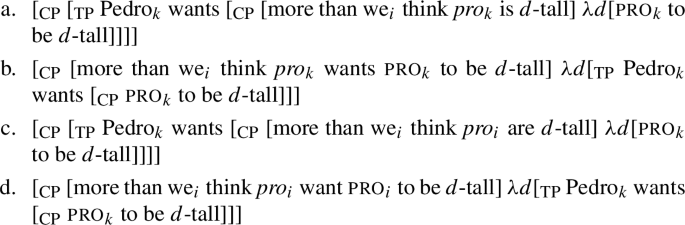

The example in (71) is 5-way ambiguous, with interpretations (71a)-(71d) being resolved by a finite clause complement, and the one in (71e) being resolved by a non-finite complement. These can be obtained by making QR available to different positions in the structure. Let’s focus on the four finite ACD sites first with pensar meaning ‘to think.’ The LFs for each interpretation are given in the bracket diagrams in (72):

-

(72)

Finite clause ACD site resolution of (71)

For (72a) and (72c), QR must take place to the edge of the embedded clause. The ACD site is resolved by copying the embedded TP. The verb pensar ‘to think’ in the standard requires that its TP complement be finite. This entails that a null pronoun must be the subject of the copied clause. There are two potential sources for pro resoltuion: Pedro or the 1pl pronoun we. Binding of pro by Pedro results in the LF in (72a), whereas binding by we results in (72c).

Contrary to this short QR, long QR of the DegP to the edge of the matrix clause renders different results. The antecedent of the ellipsis is now the whole clause: (72b) and (72d). Therefore, the ACD site includes the matrix verb want and the subject, given the finiteness requirement imposed by pensar on its complement. Again, the different interpretations arise due to a difference in binding options: if pro is bound by Pedro, so will be pro inside the ellipsis site giving rise to (72b); if pro is bound by we instead, so will pro and the interpretation that we obtain is (72d).

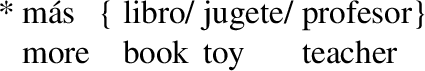

The last possible interpretation that needs some discussion is (71e) with pensar meaning ‘plan to/want to become.’ When the verb pensar has this meaning, it is a control predicate and its complement must be non-finite: the subject of pensar must control the pro in the non-finite clause. For this reading to be available, the relevant LF has to be such that QR targets the edge of the embedded non-finite clause and the ACD is resolved with the non-finite CP. pro inside the standard is then controlled by we. The LF, illustrated in (73), is similar to the one in (72c) with the crucial difference of (non-)finiteness of pensar\(_{ \textit{plan-to}}\)’s complement.

-

(73)

Non-finite ACD site resolution of (71)

Pedrok wants [CP [more than wei think\(_{plan-to}\) proi to be tall] λd[prok to be d-tall]]

These data demonstrate that QR is a neccesary mechanism to recover the ellipsis site contained within the free relative. What is more, the Ellipsis-Scope Generalization in (12) is satisfied: the DegP must contain the antecedent of the ellipsis in its scope.

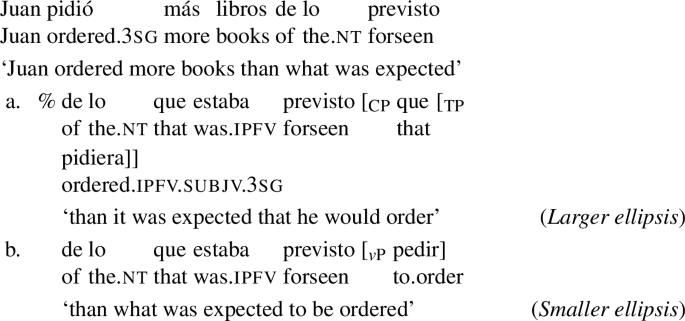

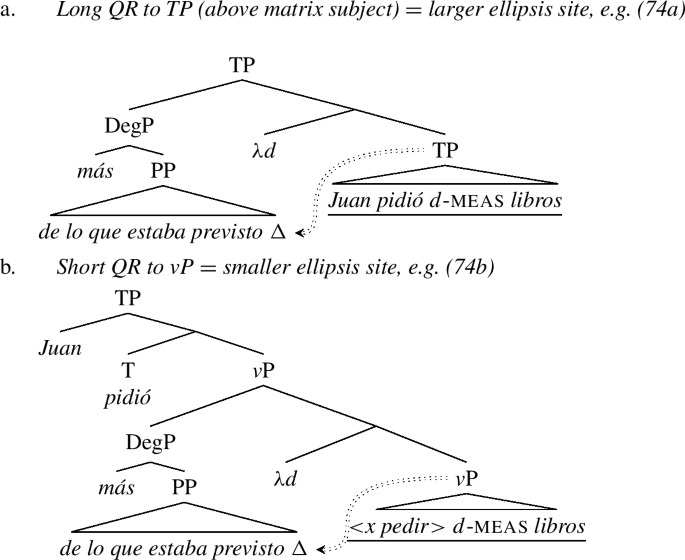

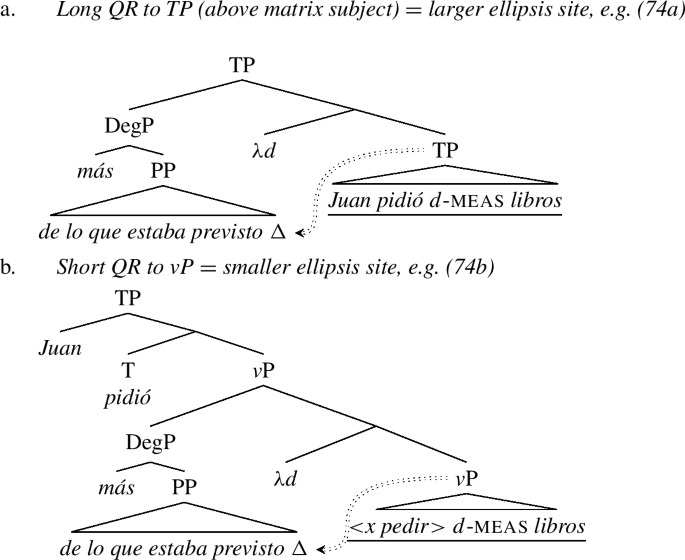

The same can be said about reduced free relatives, modulo the multiple ambiguity. It was shown in Sect. 2.2.4 that reduced relatives can also contain ACD sites, though the size of the ellipsis seemed to vary across speakers. The example used to illustrate ACD with reduced free relatives was (28) repeated as (74) for convenience:

-

(74)

In fact, it was noted that the larger ellipsis site in (74a) correlates with the possibility of inverse scope, while there is no such correlation between the smaller one in (74b) and inverse scope. This is because the landing site and height for QR are different for the two ACD options. In order to resolve the larger ellipsis site, QR must target the TP above the external argument. On the contrary, the smaller site is obtained via QR to the edge of the vP, which has been argued independently to be a scope position (Fox 1999; Legate 2003; Cecchetto 2004). The lower copy of the verb inside vP is uninflected, and so will the vP contained in the ellipsis site. The different structural options for (74) are provided in (75):

-

(75)

Given these structures in (75), the question is why inverse scope over a modal is only possible in (75a) but not (75b). The answer is that modal operators are merged into the structure higher than vP, but arguably lower than tense (Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2013). For cases like (75b), this entails that even if we reconstruct the modal to its base position (above vP), the degree quantifier will still be in the modal’s c-command domain. Thus, if these speakers do not allow the ACD site to be larger than vP, it makes sense that they do not accept inverse scope either. On the contrary, inverse scope is possible in (75a) because the DegP undergoes QR higher than T, which is the modal’s final landing site, assuming all verbs in Spanish raise to T.Footnote 34

3.5 Taking stock

I have shown how the proposal that más is a generalized quantifier over degrees can handle both clausal and phrasal-MP comparatives. The proposal has contributed to a deeper understanding of the syntax of comparative numerals, which plays a significant role in the analysis of de-comparatives. In particular, I have provided substantial evidence for a particular syntax of comparative numerals which establishes a parallelism with the syntax of numeral differential comparatives. The proposed structure has shed light on the kinds of arguments that de must take in the syntax and the semantics: de always selects a full MP and never a bare numeral or a pronominal. In fact, either of these options are found on the surface due to NP ellipsis.Footnote 35

Regarding phrasal MP comparatives more generally, I have demonstrated that, by providing a uniform syntax for más and a semantic meaning for de, the uniform analysis makes the right predictions with respect to extraposition, scope and ACD resolution. The proposal enables QR of más to a node of type t regardless of whether this node is DP/AP internal or higher up in the clause (e.g. vP, TP). Though it has been hinted that the reason for each target of QR has to be motivated—for example by the need to resolve a type mismatch or to resolve ACD—the next section is devoted to address these issues and discusses the locality of QR.

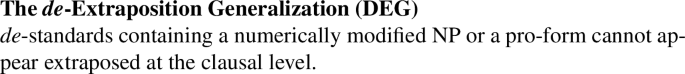

4 The locality and height of QR

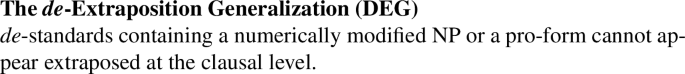

In Sect. 2.2.2 I formulated a generalization that focused on the relation between clausal extraposition and phrasal comparatives. The generalization, stated in (17), is repeated in (76) for convenience:

-

(76)

The de-Extraposition Generalization (DEG)

de-standards containing a numerically modified NP or a pro-form cannot appear extraposed at the clausal level.

This generalization was complemented by the generalization on Table 1, which has been updated as Table 2. According to Table 2, there can be different diagnostics to probe the locality of QR.

Más is a quantifier and it will have to QR to avoid a type mismatch at the base position. In addition, QR enables a particular kind of ellipsis, and since the size of ellipsis corresponds to the height of QR—an independent generalization due to Sag (1976) and Williams (1974, 1977)—the small ellipsis size in NPs needs just a short QR. Thus, since numeral or pronominal standards only show instances of the latter, the degree quantifier must QR to the closest node where it can satisfy that property and resolve the type mismatch: the NP domain. As a result, the standard cannot surface to the right of the clause; it must remain DP-internal. On the contrary, since resolving ACD and obtaining inverse scope involve longer movements, to nodes at the clausal level, surface extraposition of the standard into the clause is guaranteed.

In other words, the conditions that determine the length of QR depend on the diagnostics that we are using to test for it. For example, QR is typically regarded as a clause-bounded operation but under certain circumstances, such as the need to resolve ACD, a quantificational element can QR outside of the containing clause (Kennedy 1997a; Wilder 1997; von Fintel and Iatridou 2003; Cecchetto 2004). In fact, as argued by Cecchetto (2004), there are three main motivations for QR: to resolve a type mismatch, to get inverse scope or to avoid the problem of infinite regress in ACD configurations. These are the operations described in Table 2. I adopt a version of Scope Economy (Fox 1999, 2000, 2002; Cecchetto 2004) such that every step of successive cyclic QR must be independently motivated by at least one of the operations mentioned.Footnote 36

If we take a de-standard with a numerically modified NP, the degree operator must QR (i) to resolve a type mismatch and (ii) for the ellipsis site to be resolved appropriately under identity. The degree operator could in principle raise to a DP-internal node (May 1985; Heim and Kratzer 1998; Hackl 2000; Matushansky 2002) or to the vP edge (Legate 2003). However, the longer movement is not motivated since the only ellipsis to be resolved is that of the NP. Thus, QR beyond the DP is ruled out by Scope Economy.

The situation is identical in the case of degree-denoting pronouns, e.g. de esod, considering that pronouns are definite determiners whose complement has undergone ellipsis (Postal 1966; Elbourne 2001, 2005). A Vocabulary Insertion rule (Halle and Marantz 1993) is responsible for spelling out D as eso at PF.

The situation is different with free relatives. I have provided evidence that the need to resolve ACD triggers long QR. In fact, examples like (71) were ambiguous depending on the landing site of QR: embedded or matrix clause.Footnote 37 Long QR of this type predicts that interaction with intensional predicates should in fact be possible. This prediction was also borne out as illustrated in Sect. 2.2.3. Unlike for numeral and pronominal standards, where there was no motivation to abandon the more local position, QR is motivated to obtain inverse scope, and thus allowed by Scope Economy.

The same holds for reduced free relatives, though more inter-speaker variation should be factored in. We also found cases in which the size of the ACD site could vary: vP or TP. Regardless of the size of the ellipsis, both options in (74) support the hypothesis that the degree quantifier must QR at least as high as the vP. For some speakers, QR to the highest TP node is also available as indicated with (74a), where the external argument Juan is reconstructed inside the ellipsis site.

Regarding scope with respect to intensional predicates, only those speakers who accept larger ellipsis sites are able to find sentences like (22) and (23) felicitous with the inverse scope. As mentioned at the end of Sect. 3.4, this is expected if modal operators are (reconstructed) higher than vP, but lower than T (Iatridou and Zeijlstra 2013). As a result, if the speaker’s grammar does not find a motivation to posit QR higher than vP, neither inverse scope nor large ACD will be allowed. This is also borne out (see fn. 14).

In conclusion, I have made use of a version of Scope Economy, based on Fox’s (1999, 2000, 2002) and Cecchetto’s (2004), such that every step of successive cyclic QR must be independently motivated by at least one of these operations: type mismatch resolution, NP ellipsis, inverse scope and ACD resolution. I have then argued why QR, when de takes MPs including numerically modified NPs and degree-denoting pronouns, must always be extremely local: the type mismatch and the NP ellipsis are resolved by positing a DP/aP internal scope position. Since the ellipsis site can be resolved locally, QR to a structurally higher position is ruled out by Scope Economy. Thus, the lack of scope interactions with modals and the lack of clausal extraposition follow. With respect to free relatives, long QR is allowed by Scope Economy due to two major reasons (each of them independent from the other): the possibility to resolve ACD and inverse scope.

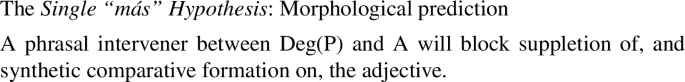

5 Comparing the current uniform analysis with Mendia’s (2020)

I have advocated for a uniform analysis of comparatives, according to which más is a generalized quantifier with the same syntax and semantics across the board. Any observed differences between comparative constructions stem from the syntax and semantics of the standards of comparison. We can refer to this as the Single “más” Hypothesis. The hypothesis is also grounded on a robust cross-linguistic observation: there is no language that we know of that uses different comparative morphemes, e.g. compr1 and compr2, to make a distinction between phrasal and clausal comparatives; the morpho-syntactic—and semantic–distinction is always found on the standard (Pancheva 2006; Bale 2008; Bhatt and Takahashi 2011; Bobaljik 2012: a.o.).

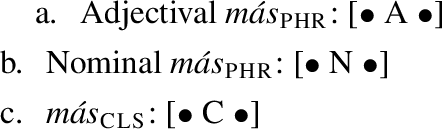

This is not the only possible account. In fact, an alternative has been developed by Mendia (2020) who proposes that the source of the distinct properties is not the standard but the comparative morpheme: más is ambiguous between máscls (i.e. clausal más) and másphr (i.e. phrasal más). We can refer to this as the Two “más” Hypothesis. In this section, I will briefly summarize Mendia’s main proposal and motivations and then I will discuss some potential challenges that it faces compared to the Single “más” Hypothesis.

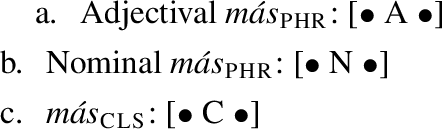

5.1 Mendia’s (2020) clausal más

Mendia adopts Bresnan’s (1973) “classical analysis” for máscls, represented in (29): máscls and the que-standard form a DegP constituent at base-structure which occupies a specifier position of the phrase it modifies. Semantically, Mendia follows Heim (2001) and analyzes máscls as a generalized quantifier of type 〈〈dt〉,〈dt,t〉〉: máscls composes with the que-standard and then the whole DegP undergoes QR to a higher node. Mendia motivates this analysis for máscls based on clausal extraposition of que-standards and the availability of inverse scope with modal operators.

This is largely identical to the analysis that I have proposed. The only difference is that I am assuming Bhatt and Pancheva’s (2004) version of the classical analysis, according to which the standard is late-merged after QR of más. As a quantifier, -er/más is non-conservative (Keenan and Stavi 1986; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004), and traces/copies are interpreted as variables bound by λ-abstracting nodes (Heim and Kratzer 1998; Fox 2001, 2002). When the interpretation of traces/copies is combined with the non-conservative semantics of -er/más, early merger of the standard of comparison and the interpretation of its copy after QR leads to a contradiction—the standard is interpreted twice (i) as the restrictor of -er/más, and (ii) inside the second argument of -er/más. Late-merger of the standard avoids the contradiction: after QR of -er/más, all that is left to deal with is the lower copy of the quantifier.Footnote 38 Mendia (2020) does not make the late-merger assumption and thus the analysis faces the non-conservativity problem.

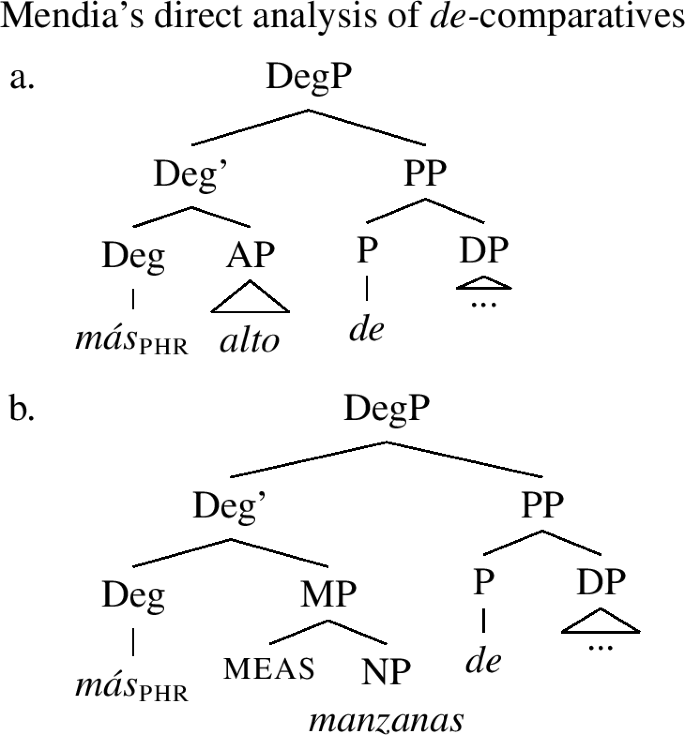

5.2 Mendia’s (2020) phrasal más

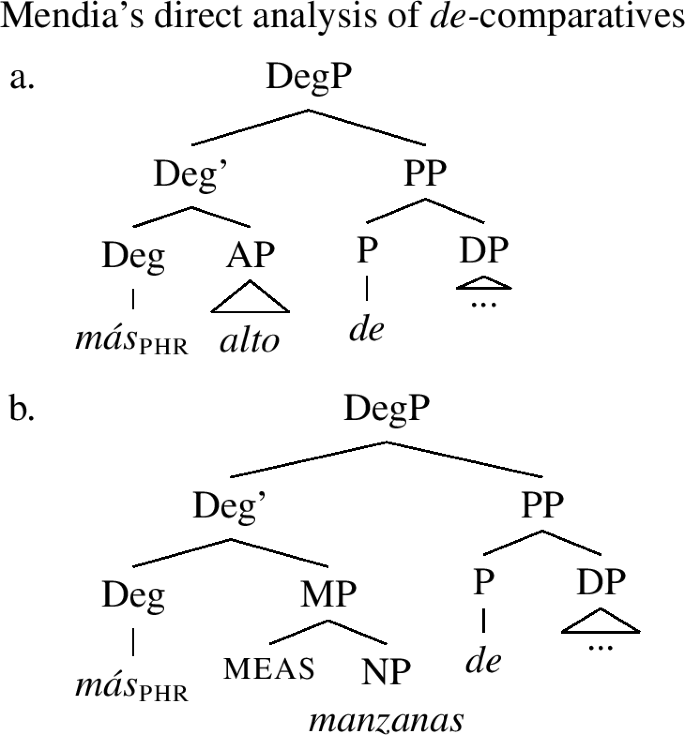

When discussing de-comparatives, Mendia (2020) assumes a different syntactic structure: másphr and the de-standard are never in a head-complement relationship. Instead, the complement of másphr is the gradable predicate. This syntactic geometry follows the “direct analysis” of comparatives (Abney 1987; Larson 1988; Corver 1990, 1997; Kennedy 1997b, 1999; a.o.). In the case of adjectival comparatives, másphr and the adjective are heads in the same extended projection; the standard is a right-adjoined adjunct. The same is true of nominal comparatives: másphr is a head in the Noun’s extended projection (Mendia 2020: p. 613, ex. 81). The relevant structures are in (77).

-

(77)

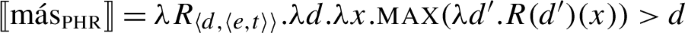

Semantically, másphr is not a quantifier but a three place predicate: it takes a gradable predicate, the de-standard of type d, and an individual. In this case más does not QR, and is interpreted in its base position (Kennedy 1997b, 1999). The denotation for másphr is in (78).

-

(78)

Mendia (2020) argues for the entry in (78) based on the following two observations: de-standards can never appear extraposed into the clause and másphr does not take inverse scope over modals.

As is, however, there are a series of challenges that Mendia’s analysis of de-comparatives faces. I comment on these below.

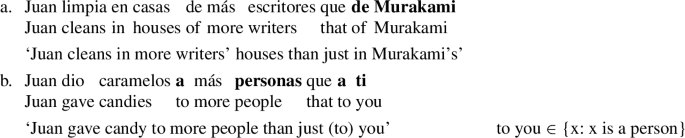

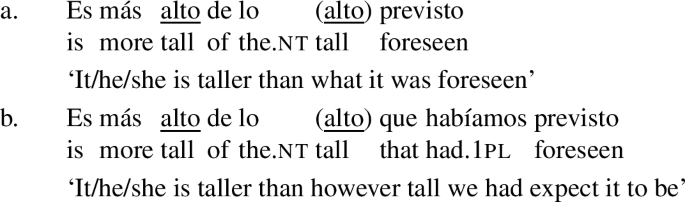

Challenge i: Extraposition, inverse scope and ACD.

As I have shown in Sects. 2.2.2 and 2.2.3, and summarized in Table 2, the observations which Mendia’s conclusions are based on are not entirely accurate. While de-standards hosting numerically modified NPs and degree-denoting pronouns cannot appear extraposed into the clause, de-standards introducing free relatives may, though. Furthermore, when the standard is able to appear extraposed higher than vP, inverse scope interpretations are grammatical. To this, we need to add the Ellipsis-Scope Generalization and the ACD facts discussed in Sect. 2.2.4. All in all, the direct analysis misses important generalizations concerned with the distribution of de-comparatives. All these facts, however, can be straightforwardly derived if más is a quantifier as I have shown.

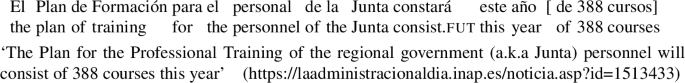

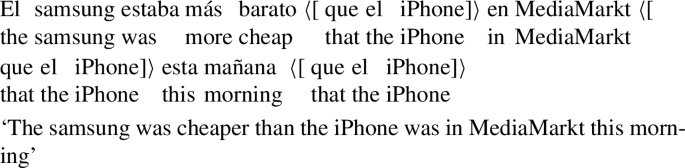

One might wonder, as one reviewer does, whether these facts, and in particular extraposition, can be explained by alluding to Heavy NP Shift: numerically modified NPs and degree-denoting eso are “lighter” than free relatives. If this were the case, the difficulty of extraposition for de-comparatives would be determined by a more general ban on smaller constituents: “heavier” PPs (e.g. de+free relatives) are easier to extrapose than “light” ones (e.g. de+numeral/eso).Footnote 39

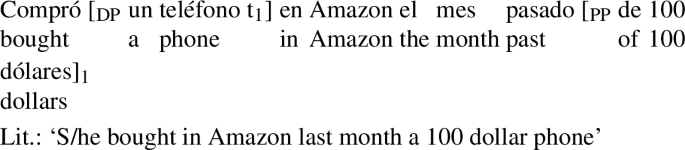

While I agree with the reviewer that extraposition of “heavier” constituents is easier and has been observed in the literature (Ross 1967; Baltin 1978, 1987), there are empirical arguments indicating that extraposition of de-standards is not driven by heaviness. First of all, heaviness only affects DP-extraposition. Other constituents such as PPs and CPs are exempt from the heaviness requirement—a fact also observed by Drummond (2009) for English. Consider the examples in (79):

-

(79)

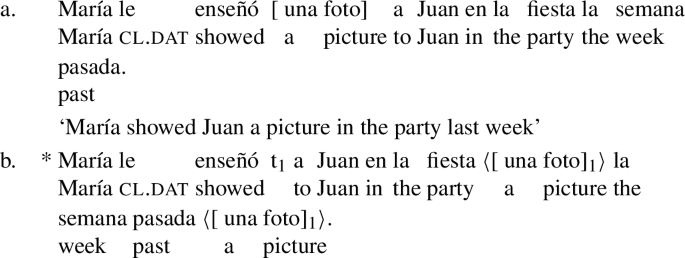

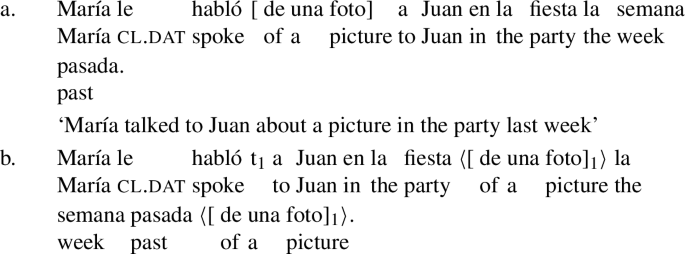

In (79a), the direct object una foto ‘a picture’ is light and occupies its unmarked position—i.e. higher than the indirect object (Demonte 1987, 1995; Cuervo 2003). When it moves to the right past the adjuncts as in (79b), ungrammaticality obtains. These data in (79) contrast with the extraposition of a light PP, shown in (80) and (81):

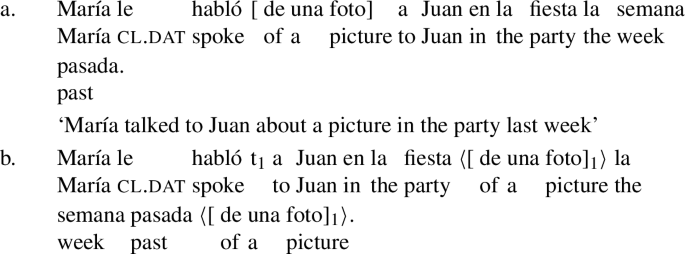

-

(80)

-

(81)

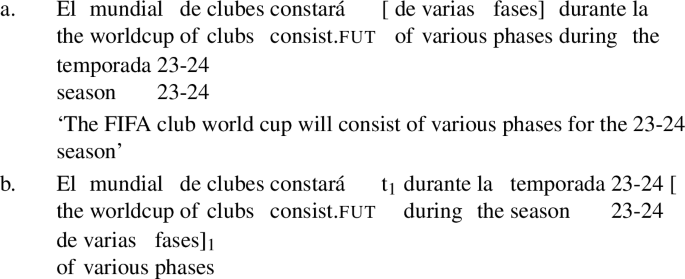

The PP de una foto ‘of a picture,’ which is a required complement of the verb hablar ‘to speak (about),’ is also light: in addition to the preposition, it only contains a two-word DP. Despite its lightness, the PP can undergo extraposition past the adjuncts as in (80b). Likewise, the PP-complement of constar ‘consist (of)’ in (81), which is obligatory and cannot be dropped, is also light and can appear extraposed as in (81b).Footnote 40

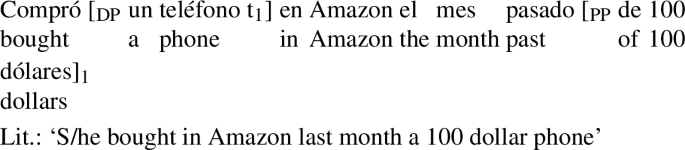

Numerically modified phrases like 100 dólares ‘100 dollars’ can also extrapose in non-comparative contexts despite the fact that they are not very heavy: compare (82) below with (14).

-

(82)

In addition to this, evidence that such PP-extraposition, including phrasal standards, is not affected by heaviness is supported by subextraction from subjects. Subjects are typically islands for extraction (Wexler and Culicover 1980), but their islandhood is voided in the passive (for Spanish, see Torrego 1984; Gallego 2010; Toquero-Pérez 2021). Extraposition of a DP-internal de-PP can occur from the subject position in Spec,vP as in (83):

-

(83)

Nevertheless, if an equally heavy de-PP standard is attempted to be extraposed from the same passive subject, the sentence is ungrammatical. This is illustrated in (84):

-

(84)

The data in (84) reinforce the observation that PPs can easily extrapose into the clause regardless of heaviness (Drummond 2009) or whether they are optional or obligatory. Thus, de-standards, which are also PPs, are not expected to be subject to this requirement. In fact, reduced free relatives are also light, i.e. they are two-word DPs, and can surface extraposed into the clause. The surface order restrictions that certain de-standards are sensitive to must be determined by a different requirement.Footnote 41

Challenge ii: Constituency, selection and the syntax of comparative numerals.

Mendia’s (2020) proposal does not only entail a semantic ambiguity of más; assigning two meanings for más also has the consequence of attributing a distinct, i.e. ambiguous, underlying syntax for the comparative morpheme. Under the direct analysis for de-comparatives, the de-standard is not the syntactic complement of másphr, but it is adjoined to the projection that dominates más and its complement, e.g. (77). This syntactic structure fails to capture the c-selectional restrictions that exist between the comparative head and the standard of comparison (Bresnan 1973; Carlson 1977; Bhatt and Pancheva 2004; Bhatt and Takahashi 2011). This is specially problematic if we take c-selection as strong evidence for head-complement relations (Chomsky 1957, et seq.).Footnote 42

This issue about the constituency of más and the standard is related to the the syntax of comparative numerals. As I have argued building on Arregi (2013), the comparative morpheme and the standard must form a constituent. This goes against the geometry in (77b). What is more, if such a syntactic analysis is on the right track, there are important consequences for the semantic composition proposed by Mendia (2020) in (78): másphr requires its first argument to be saturated by the gradable predicate of type 〈d,〈et〉〉, but given the alternative motivated constituency it must be saturated by the standard of type d or 〈dt〉. Thus, the derivation should crash.

Under the uniform analysis of comparatives, none of these present an issue: (i) más and the standard are always in a head-complement relation at some point in the derivation, and (ii) the standard of comparison always saturates más’ first argument.

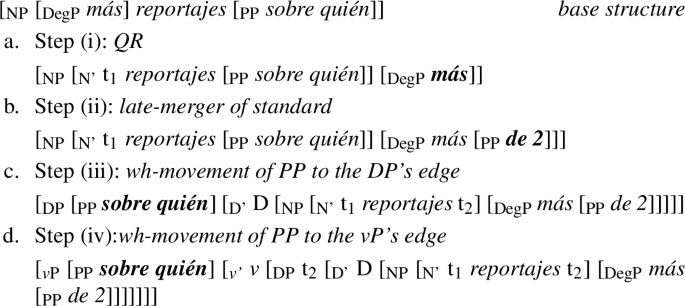

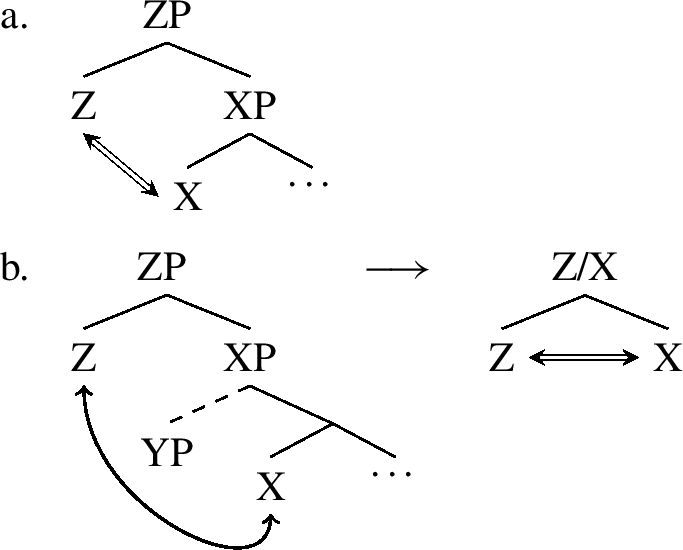

5.3 Distinguishing between the two analyses: Suppletion and synthetic comparatives

In addition to the different predictions that the two analyses make with respect to the syntax and semantics of comparative constructions, there are also distinct morphological predictions that are worth discussing. These are concerned with the formation of suppletive comparative formation on adjectives.

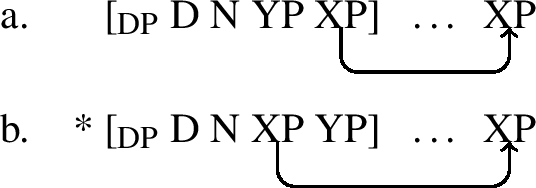

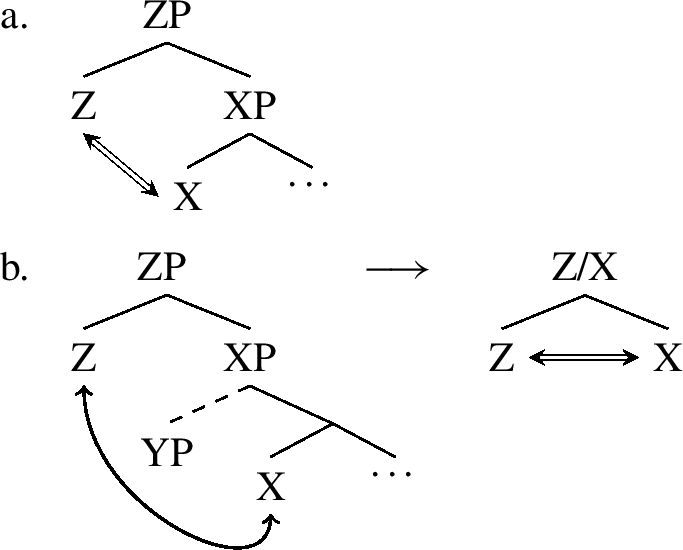

Suppletive vocabulary items are subject to stringent locality conditions: the trigger and the target of suppletion are required to be structurally adjacent post-syntactically (i.e. after spell-out) (Bobaljik 1995b, 2012; Embick and Noyer 2001; Embick 2007, 2010; Dunbar and Wellwood 2016; Bobaljik and Harley 2017). There are two potential ways that fall under the label structural adjacency: the two heads are part of the same extended projection in (85) or they belong to different extended projections in (86). The double arrows indicate that the two elements are structurally adjacent.

-

(85)

X and Z are both heads in the same extended projection

-

(86)

Z heads ZP which is a specifier of X

X and Z are part of the same extended projection and Z immediately c-commands X in (85a). Their structural adjacency can be preserved even if there is a phrasal intervener YP between Z and X via incorporation as depicted in (85b) (Emonds 1976; Travis 1984; Baker 1988; Noyer 1992; a.o.). The adjacency is only blocked if there is an additional head Y located between X and Z. On the contrary, Z and X in (86a) are not part of the same extended projection: Z is a head of ZP located in the specifier of X. They are (“linearly”) adjacent because there is nothing that intervenes between them. In case of an intervener, e.g. YP, adjacency is blocked as in (86b) (Marantz 1988; Embick and Noyer 2001).

The different syntactic structures and scenarios described have implications for suppletion. In (85), a head Z can trigger suppletion of X unless there is a head Y that intervenes between them. On the contrary, in (86) Z in ZP can trigger suppletion of X if and only if there is no intervener there is a YP that is closer to X than ZP.

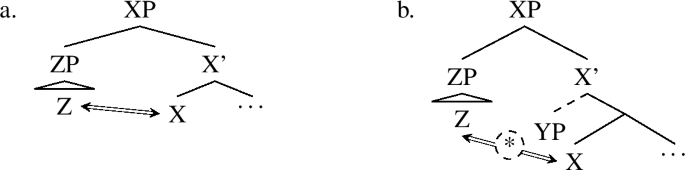

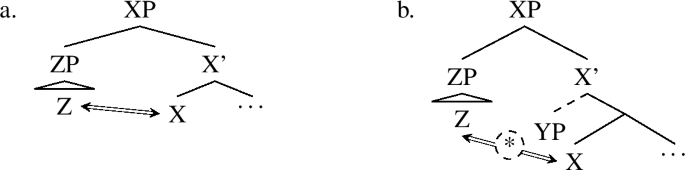

Implications and predictions for analyses of Spanish comparative constructions.

The two schematic structures in (85) and (86) remind us of the different syntactic geometries for que and de-comparatives: (30a) = (86a) and (77) = (85a), respectively. Given that the two structures make different predictions with respect to suppletion patterns, we can test them to distinguish between the two competing analyses. The relevant patterns involve suppletion of the adjective triggered by the comparative.

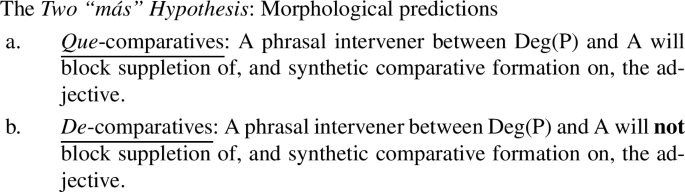

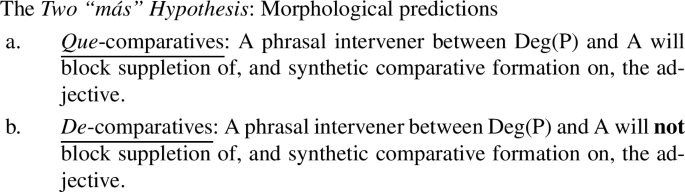

The Two “más” Hypothesis predicts an asymmetry between que and de-comparatives with respect to the suppletion and synthetic comparative formation patterns, given the two distinct structures it rests upon. The predictions are outlined in (87):

-

(87)

(87a) predicts that the comparative will not trigger suppletion on the adjective if más heading the DegP is in a specifier position, e.g. (86b). The comparative is expected to be analytic, rather than synthetic. (87b) predicts that the comparative will trigger suppletion of the adjective if más is a head in the extended projection of the adjective, e.g. (85b). The comparative will be synthetic.

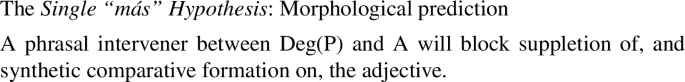

On the contrary, the Single “más” Hypothesis that I proposed in this paper is grounded on a single syntactic structure: the Deg(P) is a specifier of the element it modifies, including adjectives. Thus, we expect no asymmetry in suppletion or synthetic comparative formation. In fact, the prediction given in (88), is the same as the one made by the Two “más” Hypothesis for que-comparatives.

-

(88)

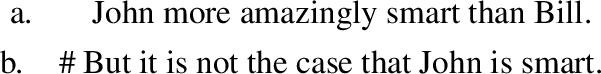

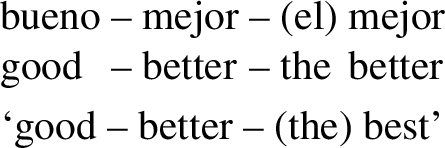

Let’s start with the observation that Spanish has very few synthetic comparative adjectives, and the few available are also suppletive. An example is given in (89).

-

(89)

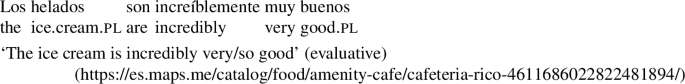

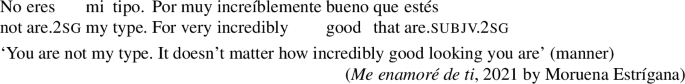

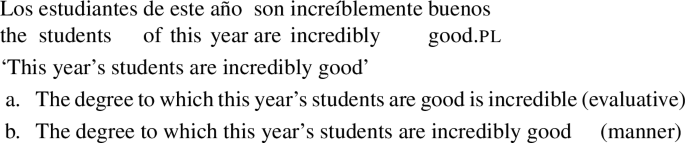

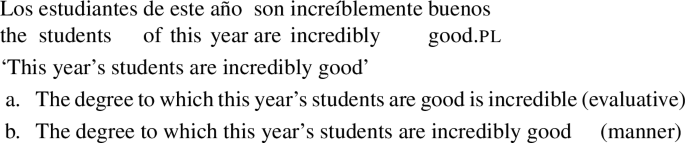

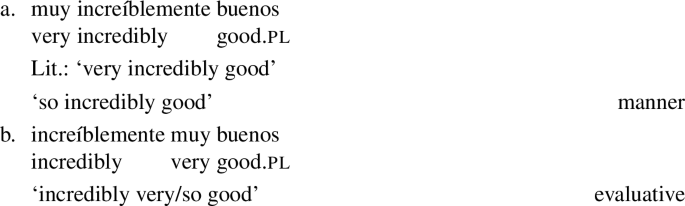

As observed by Embick (2007) and Dunbar and Wellwood (2016), some adverbials like increíblemente ‘incredibly’ are ambiguous between two possible interpretations when modifying an adjective in predicative position. One interpretation is “evaluative” and the other describes the manner (or degree) in which the subject of the predication instantiates the property denoted by the adjective. An example with the positive form of the adjective bueno ‘good’ is given in (90), with the corresponding paraphrases.

-

(90)

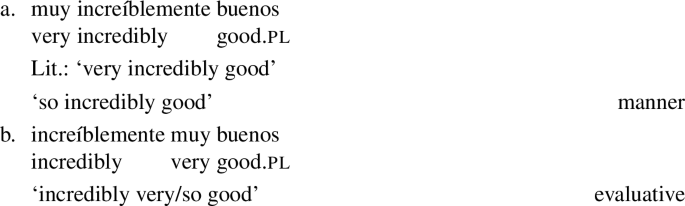

The interpretive ambiguity has been argued by these authors to be the result of a structural ambiguity. The “evaluative” reading is obtained when the adverbial is structurally higher than the position corresponding to the “manner” interpretation (Cinque 1999, 2010; Scott 2002; a.o.): Adveval > ⋯ > A vs. Advmanner > A. This order is independently motivated based on word order patterns with degree modifiers like muy ‘very.’ When muy precedes the adverbial and the adjective, only the manner interpretation is grammatical; but, when the adverbial precedes muy and the adjective, only the evaluative one is possible. The contrast is shown in (91).Footnote 43

-

(91)

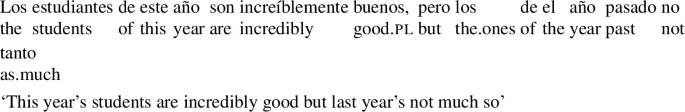

The data in (91) are crucial because they show that Deg(P)s are structurally higher than the AdvP conveying a manner reading: Adveval > Deg > Advmanner > A.Footnote 44

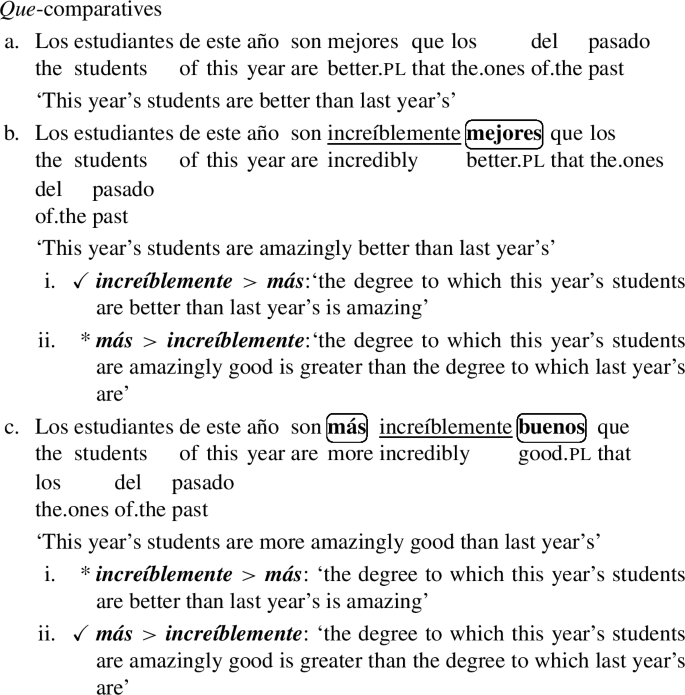

Thus, the question is whether an adverbial like increíblemente with a manner interpretation blocks the suppletion of the adjective triggered by the comparative morpheme, resulting instead in the analytic form of the comparative. If it does so only with que but not de-comparatives, we will have found support for Mendia’s (2020) Two “más” Hypothesis. However, if the suppletive form is always blocked upon the presence of the adverbial, we will have found support for the Single “más” Hypothesis. These predictions are summarized in Table 3.

Testing the predictions i: Que-comparatives.

The relevant data for que-comparatives are shown in (92). (92a) is the baseline illustrating that suppletion/synthetic comparative formation are possible.

-

(92)

In (92b), the adverbial increíblemente precedes the suppletive comparative adjective. However, what is crucial is that the sentence is only grammatical with the evaluative interpretation where the AdvP is higher than Deg(P) and A; and it is ungrammatical with the manner interpretation. For the manner interpretation to be obtained, the analytic comparative and non-suppletive form of the adjective must be used. That is the case in (92c).

What we can conclude from this is that both hypotheses make the correct predictions with respect to que-comparatives: an intervening AdvP blocks suppletion on the adjective resulting in an analytic comparative form. Thus, we can conclude that the comparative morpheme and the adjective are part of separate extended projections and the structure must be as in (86a).

Testing the predictions ii: De-comparatives.