Abstract

Interpersonal emotion regulation involves having emotions changed in a social context. While some research has used the term to refer to instances where others are used to alter one’s own emotions (intrinsic), other research refers to goal-directed actions aimed at modifying others’ emotional responses (extrinsic). We argue that the self-other distinction should be applied not only to the target (who has their emotion regulated) but also to the means (whether the agent uses themselves or others to achieve the regulation). Based on this, we propose interpersonal emotion regulation can take place when an agent changes a target’s emotions by affecting a third party’s emotion who will shift the emotion of the target in turn (direct other-based interpersonal ER) or by impacting a third party’s emotion (indirect other-based interpersonal ER). We discuss these processes and the conditions that lead to their emergence reconciling findings from different fields and suggesting new research venues.

Similar content being viewed by others

Every day in our social interactions we have our own and others’ emotions changed. For example, during conversations between romantic couples about a negative event affecting one of them, the other partner may feel bad about the situation (i.e., having their own mood shifted from positive to negative). In response, they may attempt to change how their partner is feeling (i.e., aiming to change the partner’s emotion from negative to more positive). This form of emotion regulation (ER) has been labelled interpersonal ER and entails an agent (usually the self) who takes direct actions to modify the emotions of a target (another person; Niven, 2017). This process differs from intrapersonal ER in who the target is: In interpersonal ERFootnote 1 the target is another person, in intrapersonal ER it would be the self (Gross et al., 2011). In this paper, we propose that this self-other distinction can be applied not only to the ends (i.e., who the target of the regulation is) but to the means (i.e., whether the person uses the self or others to change the emotional response). Consequently, we suggest that interpersonal ER can take two different forms: first, self-based interpersonal ER entails the agent aiming to change someone else’s emotions, but they do this directly by using their own strategies and resources (e.g., a child decides to make their friend feel better by talking to them and offering a listening ear). This is the process that has been typically described in the literature. Second, considering others as both means and ends suggests a new process that we labelled other-based interpersonal ER which will be the main focus of this paper.

Other-based interpersonal ER extends previous conceptualisations of interpersonal ER in several important ways. First, while self-based interpersonal ER assumes a dyadic interaction between an agent and a target (even if one of them is a group), other-based interpersonal ER expands this by acknowledging that there may be other actors involved in this process. This recognises that most social interactions take place in contexts where there are multiple people involved (e.g., family gatherings, team meetings, group work in the school context). Second, while self-based interpersonal ER suggests that the regulation happens in a specific direction (i.e., the agent either improves, worsens, or maintains the affect of the target), in other-based interpersonal ER the emotional valence of the different emotional exchanges might not necessarily go in the same direction. For example, an agent may make a third party feel bad (affect worsening), as this will cheer up the target as a result (affect improvement). This recognises the intricate nature of socio-emotional interactions in the interpersonal ER framework, including processes previously described in other fields such as family or group dynamics. Third, self-based interpersonal ER assumes a linear process in which the agent identifies the emotions of the target and selects and implements a number of regulation strategies (e.g., Nozaki & Mikolajczak, 2020). Although this process can require a certain degree of perspective-taking or theory of mind to represent others’ emotional states (Reeck et al., 2016), it can also take place due to more basic mechanisms such as classical conditioning (i.e., learning how to respond when one encounters someone upset) or mimicry or facial imitation (e.g., Eisenberg & Strayer, 1990; Wang et al., 2023). However, other-based interpersonal ER assumes a more complex cognitive mechanism in which the agent needs to represent two different emotional states. This extends current conceptualisations of interpersonal ER by highlighting that different forms of this process may vary in the complexity of the mechanisms involved. Finally, we argue that other-based interpersonal ER can expand current conceptualisations of interpersonal ER by integrating concepts referring to emotional dynamics that have received different labels across distinct fields (e.g., family, sports, or forensic contexts among many others) so that they can all be explained relying on a single framework. Therefore, in this paper, we will describe other-based interpersonal ER, its relevance, the different factors that may shape it, as well as the different applications and implications across different fields in psychology.

Other-based interpersonal ER

There are instances in which agents might not want or cannot directly change the emotion of the target and they need to rely on a third party or assume that third-party regulation would be more successful than directly changing the emotion of the target. We suggest that other-based interpersonal ER can occur in two ways: Direct and indirect. Direct other-based interpersonal ER involves the agent actively changing a third party’s emotions so that the third party can then alter the target’s emotions. For example, parent A (agent) may want to hurt parent B (target) by making their child (third party) feel guilty about not spending enough time together so that the child can, in turn, reject parent B (Fig. 1). On the other hand, indirect other-based interpersonal ER happens when the agent wants to change the target’s emotions by modifying a third party’s emotions without the need for the third party to change the target’s emotions. For example, a manager (agent) may make a senior employee (third party) laugh, improving their feelings so that this act makes a new employee (target) feel relaxed in their new work environment when witnessing this (Fig. 1). Although these processes can be understood as self-based interpersonal ER since the agent changes directly the emotions of the third party, we argue self- and other-based interpersonal ER are significantly different as the regulatory process serves different regulatory goals. While in self-based interpersonal ER the regulatory goal is first-order (i.e., the final aim is to change the emotions of a person or a specific group) in other-based interpersonal ER the regulatory goals are second-order, that is, they are undertaken with the final aim not to change the third party’s emotions per se but doing it with the ultimate goal to shift the target’s emotions.

Direct other-based interpersonal ER

This regulation process may happen when the agent knows that they can change the target’s emotions by impacting a third party person’s emotions, who will change the target’s emotions in turn. This emotional process can occur in different contexts (e.g., family, workplace, etc.), may involve affect improvement (i.e., enhancing others’ positive emotions) or worsening (i.e., deteriorating others’ emotions), and may be done for different motives (e.g., hedonic, that is, for the sake of improving or worsening others’ affect; instrumental with the aim for the target to attain a different goal by experiencing either a positive or a negative affect; see Table 1 for a glossary of key terms used in the paper). Regarding affect improvement, a coach (agent) may try to boost the captain’s mood (van Kleef et al., 2019) so that the captain (third party) can in turn boost the morale of the team (target) to make them feel better (i.e., hedonic) or to improve how they feel so that they can perform better in the competition (i.e., instrumental; Campo et al., 2016). This may happen in instances where the target (team) may feel closer or may have more trust in the third party (captain) as compared to the agent (coach) and as such, the regulatory efforts are more likely to be successful using this route rather than self-based interpersonal ER (Fransen et al., 2014).

Considering affect worsening, episodes of triangulation in family dynamics where separation and divorce have happened can exemplify this process. In these contexts, one parent (agent) engages in abusive behaviours making the child (third party) feel bad so that the child can in turn upset the other parent (target) by rejecting them or not wanting to spend time with them (Baker, 2005; Gardner, 2002). In this process, the agent (parent A) aims to hurt the target (parent B) but instead of doing it directly uses a third party (the child) with the ultimate goal of worsening the target’s feelings (Darnall, 2011) or for instrumental reasons such as damaging the relationship between the target and the third party (Harman et al., 2018) or for negatively impacting the reputation of the target (Gardner, 2002). Another example can be found in organisational contexts where an employee (agent) may highlight instances where the manager was unfair to their work colleagues (third party) to worsen their mood so that they in turn could ostracise the manager (target) to just worsen their affect (i.e., hedonic) or to worsen the target’s affect so that the manager might be more likely to quit the job (instrumental; Bedi, 2019).

Indirect other-based interpersonal ER

This regulation process may take place when the agent knows that they can change the target’s emotions just by impacting a third-party’s emotions. This process can again entail affect improvement and worsening and can be driven by different motives. Focusing on affect improvement, the use of affinity seeking and maintaining strategies in the family context is an example of this process (e.g., Ganong & Coleman, 2017). For instance, a step-parent (agent) may try to get on well with the step-child (third-party) and make the step-child feel good so that this in turn can cheer up the partner and parent of the child (target; e.g., Ganong et al., 1999). This may be done for the sake of making the partner feel good, that is, for hedonic considerations (e.g., Coleman & Ganong, 1997); or potentially to improve family dynamics and attain increased trust and love from the partner, that is, for instrumental or social motives (e.g., Widmer, 2016). In addition, within family dynamics, the concept of emotional spillover (e.g., Low et al., 2019) can also be explained as indirect other-based interpersonal ER as it suggests that one member (agent) affecting another member’s emotional state (third party) can also have an effect in an additional member of the family (target). For example, a child (agent) who may have failed to directly comfort their stressed parent (target), may engage in positive interactions with their sibling (third party), so that their parent will be pleased and less stressed when observing this.

We can also find examples of indirect other-oriented interpersonal affect improvement in the workplace. For instance, a worker (agent) may try to cheer up their co-workers (third party) as this is expected to please the manager (target) and ultimately make the manager happy (hedonic) or improve the company’s productivity which in turn will also make the manager happy (instrumental; Fisher, 2010). Similar interactions may also be observed in the classroom context. For instance, when a student (agent) notices their teacher (target) feeling upset, the student might have a desire to offer comfort. However, due to a perceived power imbalance that may act as a deterrent, the student might opt for an indirect approach. In this case, they choose to be kind to a peer (a third party) and try to uplift their spirits, understanding that making the peer feel happy can indirectly improve the teacher's mood as well (hedonic motive; Brackett et al., 2011). The same act can be done for instrumental reasons if making the teacher feel better is done to attain more trust and bias their academic judgment (e.g., Forster-Heinzer et al., 2020).

Indirect other-based interpersonal ER can also take place when agents engage in affect worsening. In the family context, episodes of abuse can serve as examples of these emotional processes. We can find indirect other-based interpersonal ER in situations when one member of the couple (agent) harms the child (third party) to inflict pain on the partner (target) (i.e., direct vicarious violence; Porter & López-Angulo, 2022). The anger experienced toward the partner is induced in the child so that this in turn can make the partner feel bad with the aim of hurting the partner (i.e., hedonic motive; Wilczynski, 1995) or trying to exert power and control (i.e., instrumental motive; Johnson, 2008). This is done particularly in instances when the agent (i.e., aggressor) does not have direct access to the target (i.e., partner) due sometimes to legal requirements of social distancing between partners (Porter & López-Angulo, 2022). In fact, separation from the partner (i.e., physical distancing) was described as an important risk factor for this emotional process (e.g., Kirkwood, 2012; West et al., 2009). Another example can be found in organizational settings where indirect upwards bullying (Branch et al., 2021) may take place and a worker (agent) may create a difficult working environment for other colleagues (third party) making them feel bad to ultimately upset their manager (target) (hedonic considerations; Ramsay et al., 2010) or for creating a power imbalance (i.e., instrumental; Patterson et al., 2018). Although affect worsening can entail most of the time a counterhedonic motivation (i.e., worsening other people’s mood to hurt them) it is also possible that affect worsening can be done for more altruistic purposes (López-Pérez et al., 2017, 2021). We argue this can also take place in other-based interpersonal ER. For instance, consider a situation where parent A (the agent) discovers that their adolescent child (the target) has started using drugs. The natural inclination for parent A may be to directly confront their child, expressing their disappointment and concern, but they are aware that such a direct approach can lead to reactance and resistance in the target (Donaldson et al., 2023). Therefore, parent A decides on an alternative strategy. They engage in a conversation with parent B, discussing the concerning rise in drug use among adolescents and the associated risks. As a result of this conversation, parent B (the third party) becomes visibly anxious and concerned. The adolescent child (the target) observes parent B's distress and, in turn, experiences a sense of guilt and regret about their own actions. This process illustrates how, by affecting the emotions of a third party, in this case, parent B, the agent (parent A) can indirectly prompt the target (the adolescent child) to reflect on their behaviour and feel upset for the sake of their long-term well-being, evidencing more altruistic forms of affect worsening.

The process of other-based interpersonal ER

Emotional valence

The emotional processes previously described assume that the emotional valence remains the same across the different transactions, that is, the emotion the agent expects to induce in the target has the same emotional valence as the emotion they induce in the third party (e.g., affect worsening from agent to the third party and affect worsening from the third party to the target). However, there may be instances of a discrepancy in valence in such emotional transactions. For example, in the family context, an agent (parent A) may engage in an action to improve the feelings of the third party (e.g., purchasing a gift to the child) so that this can infuriate the target (ex-partner/parent B) through the action itself (indirect other-based interpersonal ER; Cashmore & Parkinson, 2009) or by making the child reject the target afterwards (direct other-based interpersonal ER; Lowenstein, 2013). The opposite emotional trajectory is also plausible. In the workplace, a middle-manager (agent) may stress out workers of a company (third party) as the agent anticipates this will please the CEO of the corporation (target) (indirect other-based interpersonal ER; Peyton, 2004). In the sports context, a coach (agent), noticing one of the team players is ostracised, may decide to induce guilt in the captain (third party) so that the captain can change their behaviour towards the ostracised player (target) making the target feel better and more integrated into the team (direct other-based interpersonal ER; Bachand, 2017).

Motives

As outlined in the previous sections, other-based interpersonal ER can be driven by many different motives. While in some instances these motives may signal selfish reasons (solely the agent may benefit), there are other occasions in which other-based interpersonal ER can be cooperative (i.e., both agent and target can benefit by attaining a common goal) or altruistic (i.e., only the target benefits; Tamir, 2015). Importantly, the same other-based interpersonal ER action can be done for very different motives. Our initial example of a step-parent (agent) making the step-child feel good (third party), so that this, in turn, can cheer up the partner and parent of the child (target) might serve as an illustration. The step-parent can do this action to attempt to elicit a positive impression in their partner to enhance their partner’s liking towards them (i.e., selfish or egoistic motives; e.g., Ganong et al., 1999). Alternatively, the step-parent may do that with the ultimate goal of fostering cohesion in the family (i.e., cooperative motives; Barber & Buehler, 1996). Selfish or egoistic motives can be understood as manipulative or entailing malicious intentions, as the agent is looking to obtain a personal benefit and the change of others’ affect (even if positive) is done in an insincere manner misleading both the third party and the target (e.g., Grieve, 2011). However, altruistic and cooperative motives are not manipulative as the agent seeks the benefit of the target or both rather than just personal gain, even if potentially in the short-term there can be a potential disagreement about how the agent wants the target to feel and how the target would like to feel (Zaki, 2020). Motives are therefore independent of the emotional valence (affect improvement/worsening).

Is it manipulation?

The motives and intentions in other-based interpersonal ER are helpful to distinguish this process from other related processes such as manipulation. Psychological manipulation emerges when there is a conflict of interest between an agent (manipulator) and a target (manipulation recipient; Buss, 1987) and the agent wants the target to do something for them, act in a certain way, or change their behaviour (Bliton & Pincus, 2020). This definition is key to understanding the similarities and differences between manipulation and other-based interpersonal ER. Some forms of other-based interpersonal ER can overlap with manipulation when (a) there is a conflict of interest between what the agent wants the others to feel and how the third party and the target would like to feel and (b) the intention of the agent is insincere. However, there are instances in which other-based is undertaken with sincere intentions. This happens when the means are altruistic or cooperative and there is a match in the ends, that is, what agents want targets to feel and what targets want to feel align (even if it is only in the long-term). In addition, while manipulation exclusively targets behaviour, other-based interpersonal ER is centered on changing the emotional experience. While certainly emotions have an impact on people’s behaviour (e.g., theory of planned behaviour, Ajzen, 2011), the ultimate goal of other-based interpersonal ER is to affect the emotional experience (Niven, 2017) rather than changing the emotions to ultimately alter someone’s behaviour as described in the manipulation literature (e.g., making someone feel guilty so that they can act as we please). Another important element that distinguishes other-based interpersonal ER from manipulation is that while other-based interpersonal ER can be aimed at improving or worsening the third party’s and the target’s affect, in manipulation the feelings of the target are almost always worsened (Krause, 2012). While other-based interpersonal affect worsening may share certain strategies with manipulation (e.g., sulking to the target is called regression in Buss’ (1992) classification of manipulation strategies while in the interpersonal affect classification by Niven et al., 2009 is called rejection), other-based interpersonal ER may use other adaptive strategies that do not feature in manipulation. For example, affinity seeking and maintenance strategies in the family context would involve active listening, validation, or reassurance which do not feature as manipulation in any of the available classifications (e.g., Apostolou, 2013; Buss, 1992; Overall et al., 2009). In sum, other-based interpersonal ER differs from manipulation in regards to 1) aiming to change the feelings of the target as the ultimate goal (rather than their behaviour), 2) including not only affect worsening but improving, 3) including a wider repertoire of strategies, 4) featuring social exchanges that go beyond dyadic interactions as described in the manipulation literature (e.g., Apostolou, 2013; Buss, 1992); and 5) not necessarily being driven by insincere intentions and egoistic motives but altruistic and/or cooperative.

Conditions that may trigger other-based interpersonal ER and antecedents

Conditions

We suggest that other-based interpersonal ER is triggered by different conditions. First, this process may happen when there is a physical barrier between the agent and the target (e.g., Porter & López-Angulo, 2022) which may prevent the agent from directly changing the target’s emotions. In these instances, the agent needs to first shift a third party’s emotions so that this, in turn, affects the target (indirect other-based interpersonal ER). For example, if a parent (agent) notices their child (target) is not happy at school they cannot be in that context to change how their child feels there (contextual barrier), so they may rely on the teacher (third party) sharing their worries and potentially making the teacher feel concerned so that the teacher can make the child feel more comfortable and integrated into the classroom.

Second, other-based interpersonal ER may also happen when there is a psychological distance between the agent and the target. This psychological distance might exist because there is a lack of intimacy in the relationship, there might be a power imbalance, as in the case between an employee and a manager (Peyton, 2004), or when the target does not have enough trust in the agent (Fransen et al., 2014). In fact, the closeness between the agent and the target has been described as a critical aspect for the success of self-based interpersonal ER (Tanna & Maccann, 2023), making other-based interpersonal ER a feasible alternative when closeness between agent and target is low.

Third, this process may also happen when the agent perceives other-based interpersonal ER to be the most successful process to achieve the desired emotional effects on the target. For example, in instances of family abuse, the agent (parent A, aggressor) could worsen directly the feelings of the target (parent B, victim) but knows that making the third party (the child) feel bad will cause more intense negative emotions in the target (e.g., Bourget et al., 2007).

Finally, other-based interpersonal ER may also happen when the agent might not want to take direct responsibility for changing the target’s emotions. For example, in an organisational context, a worker (agent) might not want to directly ostracise a work colleague (target) as the agent may encounter a punishment for such actions (e.g., being fired; Robinson & Schabram, 2019); hence, making other colleagues (third party) feel resentment against the target so that all can ostracise the target might be less risky for the agent as it would allow diffusing personal responsibility (Khan et al., 2023).

Antecedents. Engaging in interpersonal ER involves thinking about what emotion the target should experience in a particular context (Niven, 2017). Hence, to engage in interpersonal ER agents need to be able to identify a potential discrepancy between the target’s current emotional state and the desired emotional state they want to induce in the target (López-Pérez et al., 2016; Netzer et al., 2015). This involves understanding that different situations may trigger distinct emotions depending on how individuals may appraise those contexts (e.g., Ellsworth, 2013; Kappas & Descôteaux, 2003). Although most research has found that emotion understanding (i.e., correctly identifying different emotional states and their possible causes and consequences) seems to be achieved by 5–6 years of age (e.g., Pons et al., 2003) there is evidence that there are significant gains even at 12 years of age (Kramer & Lagattuta, 2022). In addition, other-based interpersonal ER involves agents considering not only the emotions of the target but also the potential effects of shaping a third party’s emotions. From a cognitive perspective, this process involves a second- and even a third-order theory of mind as the agent needs to consider the emotional states of two different entities and whether the third party’s emotions may have an effect on the target (Westby & Robinson, 2014). From a developmental perspective, second- and third-order theory of mind are significantly developed by 10 years of age (Osterhaus & Koerber, 2021; Papera et al., 2019). Hence, it is probably not until late childhood that children can successfully undertake other-based interpersonal ER. In fact, strategies of indirect relational aggression that involve using others to harm the target (e.g., providing the agent false information about the target to the third party so that they can in turn spread it and harm the target), have only been documented from middle to late childhood (Archer & Coyne, 2005; Dailey et al., 2015) supporting the idea that a more advance form of theory of mind might be needed to engage in some forms of other-based interpersonal ER.

Dynamic nature of the process

It is important to highlight that the different processes outlined so far (self- and other-based intra- and interpersonal ER) are likely to co-occur or happen sequentially as ER is a highly dynamic process (Gross, 2015). For example, many processes of interpersonal ER (i.e., actions aimed at changing others’ emotions) may take place because the target decides to share their feelings with the agent in the first instance (i.e., intrinsic interpersonal ER; Rimé et al., 2020). Different studies have shown that approximately 90% of the time people talk about their emotions with others after a significant emotional event (Rimé et al., 2009; Schuster et al., 2001). Hence, it is likely that interpersonal ER may originate as a response to that emotional dynamic. In addition, polyregulation (i.e., use of multiple regulation strategies; Ford et al., 2019) may be possible with two emotional processes (i.e., other-based intrapersonal ER and self-based interpersonal ER) taking place one after the other or at the same time. In sequential polyregulation, the agent may have attempted, for example, self-based interpersonal ER without success so decides to implement other-based interpersonal ER to change the emotions of the target (e.g., parent A may have tried to worsen the feelings of parent B without the expected success so decides to worsen the feelings of the child as parent A knows this will significantly harm parent B’s feelings; Dallos & Vetere, 2011). In concurrent polyregulation, the agent may decide to implement other-based interpersonal ER while also undertaking self-based interpersonal ER to potentially maximise the success of the regulatory effort (Ford et al., 2019).

Concerning the number of different strategies used, previous research has demonstrated that using a large number of regulatory strategies does not necessarily entail better ER (e.g., Gruber et al., 2013) as it may involve negative consequences for the agent (e.g., lower well-being) and can undermine the social bond between the agent and the target (e.g., Niven et al., 2012). In fact, prior literature focused on self-based intrapersonal ER has highlighted that if the agent engages in polyregulation without considering the efficacy of the regulation strategies the ER may not work as expected (Ford et al., 2019).

Ending other-based interpersonal ER

In the emotional processes previously described, the agent undertakes a concrete action anticipating that the target’s affect will be shifted in a specific direction. However, previous research on self-based interpersonal ER has already demonstrated that there can be a mismatch between the agent and the target’s emotion goals or desired emotional responses (López-Pérez et al., 2017; Zaki, 2020). That is, what the agent wants the target to feel does not necessarily correspond to how the target actually wants to feel or indeed feels in that situation. Hence, there might be an unexpected emotional response from the target. Going back to one of our previous examples, a middle manager (agent) may stress out workers (third party) anticipating this will please the CEO (target), however, this may not be the case, if such practices go against the organizational culture, upsetting the CEO instead (e.g., Kao et al., 2014).

Given that we are defining interpersonal ER as a goal-directed process one important question is how the agent can determine when other-based interpersonal ER has been successful to stop the process. A simple answer is once the agent perceives that the target is experiencing the emotion they wanted to induce (Reeck et al., 2016). However, there may be caveats to this assertion. First, the emotion goals that the agent would like to induce in the third party and the target might not match what the target wants to feel (Zaki, 2020). In those instances, other-based interpersonal ER might be less likely to succeed or may take several iterations to attain the desired outcome. Second, the agent might experience a discrepancy in the perceived and the attained emotional experience for both the third party and the target. This happens when agents may struggle to accurately identify how the third party and the target are feeling (Reeck et al., 2016). This might be particularly relevant in individuals who have been described as exhibiting difficulties in accurately identifying the emotions of others either because they struggle to decode emotional expressions (e.g., individuals with ASD; Rump et al., 2009) or because they tend to misinterpret others’ intentions (e.g., individuals with Borderline personality disorder; Mitchell et al., 2014). As a consequence, the agent may stop before ER has happened or continue the ER process unnecessarily. Finally, it might be that the agent has to stop the process (before attaining ER) if this entails negative consequences for them such as burnout (Cohen & Arbel, 2020). In the same vein, agents can continue other-based interpersonal ER if potentially the agent can feel better after engaging in it (even if neither the third party nor the target may need to have their emotions changed; see Zaki, 2020), as this was previously found in the prosocial behaviour literature; where acting prosocially was positively linked to higher levels of wellbeing (Zuffianò et al., 2018).

Contexts in which other-based interpersonal ER might occur

Individual factors

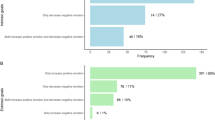

Personal characteristics can affect other-based interpersonal ER. For example, people scoring high in machiavellianism might be more likely to engage in other-based interpersonal affect worsening as they are prone to emotional manipulation. Hence, those scoring high in macheviallianism might be more inclined to engage in other-based interpersonal ER for selfish motives and insincere intentions and engaging in processes that may overalap with manipulation (see Fig. 2). Additionally, people who score high on cognitive empathy (i.e., the ability to adopt other people’s perspectives; Davis, 1983) might be better at other-based interpersonal ER as they may have the capacity to understand better how the target and the third party might be feeling (i.e., higher empathic accuracy; Zaki et al., 2008). Another factor could be people’s regulatory self-efficacy often considered a proxy of emotion regulation competence (Caprara et al., 2008). On one hand, it could be theorised that individuals with elevated levels of emotional regulatory self-efficacy and who also use a broader array of regulatory processes and strategies (e.g., Friesen et al., 2019) might be inclined to engage in other-based interpersonal emotion regulation. On the other hand, considering that other-based interpersonal emotion regulation often involves indirect and non-confrontational strategies where individuals may avoid taking direct responsibility, it is plausible that this approach is more prevalent among those with lower regulatory self-efficacy due to its connection with avoidance (e.g., De Castella et al., 2017). Therefore, future research could investigate the specific conditions that may explain the link between regulatory self-efficacy and other-based interpersonal ER.

Finally, considering the role of personality traits we would expect agreeableness, extraversion, and neuroticism to have unique associations with other-based interpersonal ER depending on the situational conditions. If the aim is to avoid personal responsibility (especially in instances of affect worsening), we would expect individuals high in agreeableness and neuroticism to rely on other-based rather than self-based processes. This is because individuals high in agreeableness try to avoid personal conflict; in fact, they have reported a lower tendency to engage in self-based affect worsening (Austin & O’Donnell, 2013). Those high in neuroticism are characterised by avoidance-motivation (Liu et al., 2013); hence, other-based would give them the possibility of avoiding confrontation with the target and diluting the responsibility potentially through the third party (i.e., responsibility displacement and diffusion). Given that people high in neuroticism try many self-based strategies when not obtaining the desired effect immediately, it is expected that they may be motivated to use other-based if self-based interpersonal ER is not leading to the desired results (Southward et al., 2018). Finally, as extroverts are motivated to use self-based interpersonal affect improvement and worsening (Austin & O’Donnell, 2013; López-Pérez et al., 2017), we hypothesise that their use of other-based interpersonal ER might be limited to instances where this process might be more successful than self-based or there might be a barrier that may prevent self-based interpersonal ER to be used, as they have a readiness to use self-based processes.

Contextual factors

Regarding context, we hypothesise that culture can play a significant role given that culture shapes how individuals emotionally respond to events (Kitayama et al., 2000) which can result in ER differences (Mesquita, 2001). For instance, individuals from cultures that do not value confrontation (i.e., a tendency to avoid conflict) might be more likely to engage in other-based interpersonal ER, especially when the aim is to worsen the feelings of the target as opposed to self-based interpersonal ER (Brett et al., 2014). Besides culture, the specific setting where other-based interpersonal ER may take place can also be relevant. Previous research has shown that ER that takes place at home allows more freedom in the implementation of ER processes (Leidner, 1999). Hence, it is likely that individuals could engage equally in direct and indirect other-based affect improvement and worsening, as evidenced in the family dynamics literature (e.g., Gardner, 2002; Porter & López-Angulo, 2022). On the other hand, emotional neutrality is normally encouraged in a workplace context (Lively, 2000). Hence, people might be less likely to engage in other-based affect worsening if negative repercussions can emerge from those actions as compared to affect improvement (Robinson & Schabram, 2019). Future research would benefit from looking at whether the specific social setting can shape the possible other-based interpersonal ER processes given that the social situation has been proposed as a relevant variable in the study of ER in general (English et al., 2016).

Clinical conditions

Interpersonal functioning is affected in many different clinical conditions. Hence, different forms of other-based interpersonal ER might be more or less present in individuals with certain conditions as compared to healthy matched controls. For example, individuals diagnosed with personality disorders often exhibit intrapersonal emotion dysregulation (Dimaggio et al., 2017) as well as deficits in interpersonal functioning (Hengartner et al., 2013). Therefore, it is likely that their interpersonal ER might be impaired. Specifically, we would expect that individuals diagnosed with paranoid and borderline personality disorder would be more prone to display other-based interpersonal affect worsening when this process could harm the target significantly more than self-based interpersonal affect worsening. Both paranoid and borderline personality disorders are characterised by a lack of trust in others as well as a tendency for people to misinterpret others’ feelings and actions which can lead them to display antisocial behaviours against others to generate the most possible harm (Garofalo et al., 2015).

On the other hand, we expect that individuals presenting with Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD) would engage in other-based interpersonal ER less as compared to healthy matched controls. Individuals with ASD are characterised by presenting an impaired understanding of others’ emotions as well as deficits in interpersonal functioning (e.g., Gillespie-Smith et al., 2017; Travis & Sigman, 1998). Specifically, we hypothesise that due to the difficulties individuals with ASD experience engaging in second- and third-order theory of mind (e.g., Livingston et al., 2018), they would find it more difficult to display other-based interpersonal ER. Finally, we also expect a potential lower engagement in other-based interpersonal ER in individuals with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), as they are characterised by exhibiting challenges in social cognition and impaired interpersonal functioning (e.g., Sibley et al., 2009). Hence, investigating other-based interpersonal ER in the aforementioned clinical conditions could help to understand the extent of the potential interpersonal challenges they experience.

Investigating other-based interpersonal ER

Motives and intentions

The same other-based interpersonal ER process can be undertaken with different motives and intentions. For example, acting nicely towards a co-worker (third party) to make the new manager (target) feel more relaxed in the workplace can be done for egoistic (i.e., impression management; DuBrin, 2010), or cooperative reasons (i.e., promoting an adequate emotional climate; Härtel & Liu, 2012). Therefore, observational methods might provide little information as to why people engage in other-oriented interpersonal ER. Experiments similar to delegation studies in economic game theory (Schotter et al., 2000) can allow for investigating motives in other-based interpersonal ER. Delegation studies include an agent, a third party, and a target but it is only the third party who can liaise with the target directly. Adapting those tasks including mood inductions can help to understand agents’ motives in other-based interpersonal ER. For example, by manipulating whether the agent gets any reward for affecting the feelings of the third party and the target we can investigate whether agents are driven by selfish or altruistic motives. In the same vein, manipulating the goal to fulfill (e.g., reaching an agreement vs competing for resources) can help study affect improvement and worsening, respectively (López-Pérez et al., 2017; Netzer et al., 2015). In addition, experimental paradigms in which conditions (e.g., power imbalance, diffusion of responsibility, or physical barrier between the agent and the target) might be manipulated could provide information about people's readiness to engage in other-based interpersonal ER. We would predict that particularly in instances when a target is aiming to diffuse responsibility other-based interpersonal ER might be preferable when aiming to worsen the feelings of the third party and/or target and the motivation might be counter-hedonic (i.e., worsening the feelings with the ultimate goal to harm the target).

Unpacking emotional dynamics

To better understand whether other-based interpersonal ER is taking place in specific contexts the use of exponential random graph models can be helpful. These statistical models analyse the structure and dynamics of social networks. Applying these techniques, it would be possible to identify the presence/absence of edges (links between agent, third party, and target), the number of connections, and whether there are specific exchanges that can detect other-based interpersonal ER dynamics by looking at the interaction between members grouped within a particular cluster (Robins, 2011). Importantly, these models can play a significant role in forecasting the occurrence of such emotional dynamics (Lusher et al., 2012). Such predictions can be especially valuable to prevent those in which other-based interpersonal ER may be done to damage the third party and the target.

Understanding emergence and development

One of the key variables to investigate how other-based interpersonal ER develops is theory of mind (ToM). ToM is the ability to attribute mental states (e.g., desires, beliefs) to others and the self to explain behaviours (Sutton et al., 1999). ToM can involve processes aimed at decoding and reasoning about mental states (Sabbagh, 2004). More developed ToM involves being capable of operating well in both levels (i.e., decoding and reasoning; Báez et al., 2014). Hence, one could expect that more developed (second- and third-order) ToM might be needed for other-based interpersonal ER to take place since agents need to decode the feelings of the third party and the target and reason about the potential effects of their actions in both. Importantly, high levels of ToM are linked not only to more prosocial behaviour (Watson et al., 1999) but also to prosocial lying (Lee & Imuta, 2021) and more relational aggression (Sutton et al., 1999). This would give support to high levels of second- and third-order ToM being needed when aiming to improve or worsen others’ (third party and target) feelings not only in a genuine way but in an insincere, manipulative manner. Future research could rely on experimental ToM tasks to evaluate whether different motivated forms of other-based interpersonal ER are more present as ToM develops. The administration of ToM tasks could be accompanied by (a) scenarios to understand how children reason about other-based interpersonal ER in different contexts across different age groups (similar procedures have been used in developmental studies to understand self-based interpersonal ER in social exclusion contexts; Gummerum & López-Pérez, 2020), (b) peer nomination procedures to then apply exponential random graph models to understand other-based interpersonal ER in the classroom, or (c) ecological momentary assessments to understand the antecents, frequency, and consequences of other-based interpersonal ER in the family context (Smyth & Heron, 2013). Using these procedures in clinical groups could provide valuable information as to whether other-based interpersonal ER is present at similar levels in clinical and healthy controls. For example, a meta-analysis found that patients with BPD experienced significant challenges in reasoning about others’ emotions (Németh et al., 2018). Hence, given that other-based interpersonal ER is hypothesised to be linked to higher levels of ToM, we might predict that other-based interpersonal ER might be different from healthy controls (e.g., might be used less frequently and/or with lower efficacy).

Applications

Other-based interpersonal ER is ubiquitous. Studying different phenomena described in the literature under the process of other-based interpersonal ER can help explain emotional dynamics of different fields, helping to connect findings across distinct disciplines (Table 2).

From a developmental perspective, family dynamics including affinity seeking and maintaining strategies (e.g., Ganong & Coleman, 2017), triangulation (i.e., the involvement of a third party to defuse dyadic conflict; e.g., Dallos & Vetere, 2011), direct vicarious violence (i.e., aggression/abuse to the child with the final aim to hurt the ex-partner; e.g., Porter & López-Angulo, 2022), emotional spillover (e.g., Low et al., 2019), or abuse and aggression based on retaliation (i.e., abuse to the child to take revenge of the ex-partner, including in extreme cases filicide; e.g., Bourget et al., 2007) can be studied considering not only the positive or negative act but the emotional processes linked to those and, importantly, the motives and strategies that may underline agents’ actions. This can help us better understand those dynamics and plan appropriate interventions. In fact, interventions focused on emotions are currently suggested to counteract risk factors that may lead to negative family dynamics such as in the case of triangulation (e.g., McCauley & Fosco, 2021). Besides the family context, socio-emotional dynamics in the peer groups can also be investigated considering the process of other-based interpersonal ER. For example, relational aggression in which an agent may use rumour to separate the target (victim) from the third party (groups of friends) by making the third party feel negative about the target can be considered a form of direct other-based interpersonal ER (e.g., Crick & Grotpeter, 1995).

The sports context would also benefit from considering other-based interpersonal ER as emotional processes are extremely relevant for team sports cohesion (e.g., Campo et al., 2019) as well as performance (e.g., Jekauc et al., 2021). Previous research has mainly focused on the emotional exchanges between an agent (e.g., coach) and a target (e.g., the athlete/team) (e.g., Kim et al., 2021). However, the use of a third party to have the emotions of the target changed might be particularly promising especially when there is a gap (e.g., lack of trust, not enough intimacy, power imbalance) between the agent and the target. For example, some of the literature has referred to captains or assistant coaches (third party) as ‘sounding boards’ who might be of help not only to listen to the concerns of the team (target) but also to change the emotions of the players, especially when these have not enough trust/confidence in the coach (agent) (e.g., McMorris & Hale, 2006).

Finally, from a social psychology stance, other-based interpersonal ER can help explain different phenomena. For example, direct other-based interpersonal affect improvement can be observed in current marketing trends in which brands (agents) may purposefully send free products to influencers (third party) so that they can experience positive emotions (e.g., De Veirman et al., 2017). They, in turn, will shape potential consumers’ (target) attitudes and emotions towards a specific brand or product (e.g., Ki et al., 2020). This process is used as brands (agents) have realized that by using influencers (third party) they can be more successful in changing potential consumers’ (targets) emotional responses and ultimately the buying behaviour, as potential buyers may identify more with the third party (e.g., Pop et al., 2021). Other-based interpersonal ER can be particularly helpful in studying romantic relationship dynamics. In the initial stages of a romantic relationship, indirect other-based interpersonal affect improvement has been described in the literature as impression management. For example, it has been found that people (agent) may decide to engage in prosocial actions towards a third party in front of the prospective partner (target) so that the target can feel good about the agent’s action and like them more (e.g., Barclay, 2010). Indirect other-based affect worsening has been documented as a strategy to generate jealousy in the ex-partner (target) by for example observing the agent having fun with a third party (e.g., Ellis & Weinstein, 1986). From a political psychology approach, other-based interpersonal ER is present in many political conflicts and even in terrorism. For instance, indirect other-based interpersonal affect worsening can be observed when terrorists (agents) may inflict violence or blackmail civilians (third party) making them feel bad so that this can in turn make a government (target) feel pressured and lead the terrorists (agents) to attain specific political goals (e.g., Ganor, 2004).

These processes are just some examples in which other-based interpersonal ER can be observed. Studying social and political processes under other-based interpersonal ER can help to understand emotional dynamics in which a third party can play a significant role in shaping the interaction between the agent and the target and importantly identifying whether there are commonalities in regards to factors that may lead to affect improvement and worsening. Overall, other-based interpersonal ER can be a useful process to consider when trying to understand emotional dynamics rather than exclusively changes in behaviours as done in prior research. In addition, considering other-based interpersonal ER gives scope to better understand the motives and final intentions involved in those processes shedding light on the similarities and differences with other psychological processes such as manipulation (Fig. 2).

Final remarks

When investigating interpersonal ER it is important to consider the distinction between self and others in the target of the regulation process but also in the means to change the emotions. We have outlined in this paper how this distinction not only expands the current conceptualizations of interpersonal ER but also brings together concepts from different disciplines that can be explained using the distinction of direct and indirect other-based interpersonal ER. We hope that the emotional processes proposed will not only move the research agenda forward but will open a new venue to better understand the complexity of ER taking place in social interactions.

References

Apostolou, M. (2013). Do as We Wish: Parental Tactics of Mate Choice Manipulation. Evolutionary Psychology, 11(4), 147470491301100. https://doi.org/10.1177/147470491301100404

Archer, J., & Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2

Austin, E., & O’Donnell, M. (2013). Development and preliminary validation of a scale to assess managing the emotions of others. Personality and Individual Differences, 55(7), 834–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2013.07.005

Bachand, C. R. (2017). Bullying in Sports: the definition depends on who you ask. The Sport Journal, 9, 1–14.

Báez, S., Marengo, J., Pérez, A., Huepe, D., Font, F. G., Rial, V., Gonzalez-Gadea, M. L., Manes, F., & Ibáñez, A. (2014). Theory of mind and its relationship with executive functions and emotion recognition in borderline personality disorder. Journal of Neuropsychology, 9(2), 203–218. https://doi.org/10.1111/jnp.12046

Baker, A. J. L. (2005). The Long-Term Effects of Parental Alienation on Adult Children: A Qualitative Research study. American Journal of Family Therapy, 33(4), 289–302. https://doi.org/10.1080/01926180590962129

Barber, B. K., & Buehler, C. (1996). Family cohesion and enmeshment: Different constructs, different effects. Journal of Marriage and Family, 58(2), 433. https://doi.org/10.2307/353507

Barclay, P. (2010). Altruism as a courtship display: Some effects of third-party generosity on audience perceptions. British Journal of Psychology, 101(1), 123–135. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712609x435733

Bedi, A. (2019). No Herd for Black Sheep: A Meta-Analytic Review of the Predictors and Outcomes of Workplace Ostracism. Applied Psychology, 70(2), 861–904. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12238

Bliton, C. F., & Pincus, A. L. (2020). Construction and validation of the interpersonal influence tactics Circumplex (IIT-C) scales. Assessment, 27(4), 688–705. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911198646

Bourget, D., Grace, J., & Whitehurst, L. (2007). A review of maternal and paternal filicide. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 35(1), 74–82. https://web.archive.org/web/20190719114750id_/http://jaapl.org/content/jaapl/35/1/74.full.pdf

Brackett, M. A., Reyes, M. R., Rivers, S. E., Elbertson, N. A., & Salovey, P. (2011). Classroom emotional climate, teacher affiliation, and student conduct. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 46(1), 27–36. http://bcps.org/offices/oea/pdf/classroom-emotional-climate.pdf

Branch, S., Ramsay, S. G., Shallcross, L., Hedges, A., & Barker, M. (2021). Exploring Upwards Bullying to learn more about workplace bullying. In Handbooks of Workplace Bullying, Emotional Abuse and Harassment (pp. 263–293). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-13-0935-9_11

Brett, J. M., Behfar, K., & Sanchez-Burks, J. (2014). Managing cross-culture conflicts: A close look at the implication of direct versus indirect confrontation. In Edward Elgar Publishing eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781781006948.00016

Buss, D. M. (1987). Selection, evocation, and manipulation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53(6), 1214–1221. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1214

Buss, D. M. (1992). Manipulation in close Relationships: Five personality factors in interactional context. Journal of Personality, 60(2), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00981.x

Campo, M., Sánchez, X., Ferrand, C., Rosnet, É., Friesen, A. P., & Lane, A. M. (2016). Interpersonal emotion regulation in team sport: Mechanisms and reasons to regulate teammates’ emotions examined. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 15(4), 379–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2015.1114501

Campo, M., Mackie, D. M., & Sánchez, X. (2019). Emotions in Group Sports: A Narrative review from a social Identity perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00666

Caprara, G. V., Di Giunta, L., Eisenberg, N., Gerbino, M., Pastorelli, C., & Tramontano, C. (2008). Assessing regulatory emotional self-efficacy in three countries. Psychological Assessment, 20(3), 227–237. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.20.3.227

Cashmore, J., & Parkinson, P. (2009). Children’s participation in family law disputes: The views of children, parents, lawyers and counsellors. Social Science Research Network. https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID1471693_code609399.pdf?abstractid=1471693&mirid=1

Cohen, N., & Arbel, R. (2020). On the benefits and costs of extrinsic emotion regulation to the provider: Toward a neurobehavioral model. Cortex, 130, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2020.05.011

Coleman, M., & Ganong, L. H. (1997). Stepfamilies from the Stepfamily’s Perspective. Marriage and Family Review, 26(1–2), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1300/j002v26n01_07

Crick, N. R., & Grotpeter, J. K. (1995). Relational Aggression, Gender, and Social-Psychological Adjustment. Child Development, 66(3), 710–722. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1995.tb00900.x

Dailey, A. L., Frey, A. J., & Walker, H. M. (2015). Relational aggression in school settings: Definition, development, Strategies, and implications. Children & Schools, 37(2), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1093/cs/cdv003

Dallos, R., & Vetere, A. (2011). Systems Theory, family attachments and Processes of triangulation: Does the concept of triangulation offer a useful bridge? Journal of Family Therapy, 34(2), 117–137. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6427.2011.00554.x

Darnall, D. (2011). The psychosocial treatment of parental alienation. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 20(3), 479–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2011.03.006

Davis, M. H. A. (1983). Measuring individual differences in empathy: Evidence for a multidimensional approach. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(1), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.44.1.113

De Castella, K., Platow, M. J., Tamir, M., & Gross, J. J. (2017). Beliefs about emotion: Implications for avoidance-based emotion regulation and psychological health. Cognition & Emotion, 32(4), 773–795. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2017.1353485

De Veirman, M., Cauberghe, V., & Hudders, L. (2017). Marketing through Instagram influencers: The impact of number of followers and product divergence on brand attitude. International Journal of Advertising, 36(5), 798–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650487.2017.1348035

Dimaggio, G., Popolo, R., Montano, A., Velotti, P., Perrini, F., Buonocore, L., Garofalo, C., D’Aguanno, M., & Salvatore, G. (2017). Emotion dysregulation, symptoms, and interpersonal problems as independent predictors of a broad range of personality disorders in an outpatient sample. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(4), 586–599. https://doi.org/10.1111/papt.12126

Donaldson, C. D., Alvaro, E. M., Siegel, J. T., & Crano, W. D. (2023). Psychological reactance and adolescent cannabis use: The role of parental warmth and monitoring. Addictive Behaviors, 136, 107466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107466

DuBrin, A. J. (2010). Impression management in the workplace. In Routledge eBooks. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203865712

Eisenberg, N., & Strayer, J. (Eds.). (1990). Empathy and its development. CUP Archive.

Ellis, C., & Weinstein, E. A. (1986). Jealousy and the social psychology of emotional experience. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 3(3), 337–357. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407586033006

Ellsworth, P. C. (2013). Appraisal theory: Old and new questions. Emotion Review, 5(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912463617

English, T., Lee, I. A., John, O. P., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Emotion regulation strategy selection in daily life: The role of social context and goals. Motivation and Emotion, 41(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9597-z

Fisher, C. D. (2010). Happiness at work. International Journal of Management Reviews, 12(4), 384–412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2009.00270.x

Ford, B. Q., Gross, J. J., & Gruber, J. (2019). Broadening our field of view: The role of emotion polyregulation. Emotion Review, 11(3), 197–208. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073919850314

Forster-Heinzer, S., Nagel, A., & Biedermann, H. (2020). The Power of Appearance: Students’ Impression Management within Class. In IntechOpen eBooks. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.88850

Fransen, K., Vanbeselaere, N., De Cuyper, B., Broek, G. V., & Boen, F. (2014). The myth of the team captain as principal leader: Extending the athlete leadership classification within sport teams. Journal of Sports Sciences, 32(14), 1389–1397. https://doi.org/10.1080/02640414.2014.891291

Friesen, A. P., Stanley, D. M., Devonport, T. J., & Lane, A. M. (2019). Regulating own and teammates’ emotions prior to competition. Movement & Sport Sciences, 105, 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1051/sm/2019014

Ganong, L. H., & Coleman, M. (2017). Stepfamily relationships. In Springer eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-7702-1

Ganong, L. H., Coleman, M., Fine, M. A., & Martin, P. Y. (1999). Stepparents’ Affinity-Seeking and Affinity-Maintaining Strategies with Stepchildren. Journal of Family Issues, 20(3), 299–327. https://doi.org/10.1177/019251399020003001

Ganor, B. (2004). Terrorism as a strategy of psychological warfare. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 9(1–2), 33–43. https://doi.org/10.1300/j146v09n01_03

Gardner, R. A. (2002). Parental Alienation Syndrome vs. Parental Alienation: Which Diagnosis Should Evaluators Use in Child-Custody Disputes? American Journal of Family Therapy, 30(2), 93–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/019261802753573821

Garofalo, C., Holden, C. J., Zeigler-Hill, V., & Velotti, P. (2015). Understanding the connection between self-esteem and aggression: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Aggressive Behavior, 42(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.21601

Gillespie-Smith, K., Ballantyne, C., Branigan, H. P., Turk, D. J., & Cunningham, S. J. (2017). The I in autism: Severity and social functioning in autism are related to self-processing. British Journal of Development Psychology, 36(1), 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12219

Grieve, R. (2011). Mirror Mirror: The role of self-monitoring and sincerity in emotional manipulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 51(8), 981–985. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.004

Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion Regulation: Current status and future Prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840x.2014.940781

Gross, J. J., Sheppes, G., & Urry, H. L. (2011). Cognition and Emotion lecture at the 2010 SPSP Emotion Preconference. Cognition & Emotion, 25(5), 765–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2011.555753

Gruber, J., Kogan, A., Mennin, D. S., & Murray, G. (2013). Real-world emotion? An experience-sampling approach to emotion experience and regulation in bipolar I disorder. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 122(4), 971–983. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034425

Gummerum, M., & López-Pérez, B. (2020). “You shouldn’t feel this way!” Children’s and adolescents’ interpersonal emotion regulation of victims’ and violators’ feelings after social exclusion. Cognitive Development, 54, 100874. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cogdev.2020.100874

Harman, J. J., Kruk, E., & Hines, D. A. (2018). Parental alienating behaviors: An unacknowledged form of family violence. Psychological Bulletin, 144(12), 1275–1299. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000175

Härtel, C. E. J., & Liu, X. Y. (2012). How emotional climate in teams affects workplace effectiveness in individualistic and collectivistic contexts. Journal of Management & Organization, 18(4), 573–585. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.2012.18.4.573

Hengartner, M. P., Müller, M., Rodgers, S., Rössler, W., & Ajdacic-Gross, V. (2013). Interpersonal functioning deficits in association with DSM-IV personality disorder dimensions. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 49(2), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-013-0707-x

Jekauc, D., Fritsch, J., & Latinjak, A. T. (2021). Toward a theory of emotions in competitive sports. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.790423

Johnson, M. E. (2008). Redefining harm, reimagining remedies, and reclaiming domestic violence law. UC Davis Law Review, 42, 1107. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1303011

Kao, F., Cheng, B., Kuo, C., & Huang, M. (2014). Stressors, withdrawal, and sabotage in frontline employees: The moderating effects of caring and service climates. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 87(4), 755–780. https://doi.org/10.1111/joop.12073

Kappas, A., & Descôteaux, J. (2003). Of butterflies and roaring thunder. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 45–74). https://doi.org/10.1093/med:psych/9780195141092.003.0003

Khan, H., Cristofaro, M., Chughtai, M. S., & Baiocco, S. (2023). Understanding the psychology of workplace bullies: The impact of Dark Tetrad and how to mitigate it. Management Research Review, 46(12), 1748–1768. https://doi.org/10.1108/mrr-09-2022-0681

Ki, C., Cuevas, L., Chong, S. M., & Lim, H. (2020). Influencer marketing: Social media influencers as human brands attaching to followers and yielding positive marketing results by fulfilling needs. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 55, 102133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2020.102133

Kim, J., Tamminen, K. A., Harris, C., & Sutherland, S. (2021). A Mixed-Method examination of coaches’ interpersonal emotion regulation toward athletes. International Sport Coaching Journal, 9(1), 111–121. https://doi.org/10.1123/iscj.2021-0006

Kirkwood, D. (2012). Heeding the warning signs : Recognising family violence as a risk for filicide. DVRCV Quarterly, 2, 1–4. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.977661610685845

Kitayama, S., Markus, H. R., & Kurokawa, M. (2000). Culture, emotion, and well-being: Good feelings in Japan and the United States. Cognition & Emotion, 14(1), 93–124. https://doi.org/10.1080/026999300379003

Kramer, H. J., & Lagattuta, K. H. (2022). Developmental changes in emotion understanding during middle childhood. In Oxford University Press eBooks (pp. 157–173). https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198855903.013.24

Krause, D. E. (2012). Consequences of Manipulation in Organizations: Two Studies on its Effects on Emotions and Relationships. Psychological Reports, 111(1), 199–218. https://doi.org/10.2466/01.21.pr0.111.4.199-218

Lee, J. Y. S., & Imuta, K. (2021). Lying and Theory of Mind: A Meta-Analysis. Child Development, 92(2), 536–553. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13535

Leidner, R. (1999). Emotional labor in service work. The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 561(1), 81–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/000271629956100106

Liu, T., Ode, S., Moeller, S. K., & Robinson, M. D. (2013). Neuroticism as distancing: Perceptual sources of evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(5), 907–920. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031969

Lively, K. J. (2000). Reciprocal emotion management. Work and Occupations, 27(1), 32–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888400027001003

Livingston, L. A., Colvert, E., Bolton, P., & Happé, F. (2018). Good social skills despite poor theory of mind: Exploring compensation in autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 60(1), 102–110. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12886

López-Pérez, B., Wilson, E., Dellaria, G., & Gummerum, M. (2016). Developmental differences in children’s interpersonal emotion regulation. Motivation and Emotion, 40(5), 767–780. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-016-9569-3

López-Pérez, B., Howells, L., & Gummerum, M. (2017). Cruel to be kind: Factors underlying altruistic efforts to worsen another person’s mood. Psychological Science, 28(7), 862–871. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617696312

López-Pérez, B., Hanoch, Y., & Gummerum, M. (2021). Coronashaming: Interpersonal affect worsening in contexts of COVID-19 rule violations. Cognition & Emotion, 36(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2021.2013778

Low, R. S. T., Overall, N. C., Cross, E. J., & Henderson, A. M. E. (2019). Emotion regulation, conflict resolution, and spillover on subsequent family functioning. Emotion, 19(7), 1162–1182. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000519

Lowenstein, L. F. (2013). Is the Concept of Parental Alienation a Meaningful One? Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 54(8), 658–667. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2013.810980

Lusher, D., Koskinen, J., & Robins, G. (2012). Exponential random graph models for social networks. In Cambridge University Press eBooks. https://doi.org/10.1017/cbo9780511894701

McCauley, D. M., & Fosco, G. M. (2021). Family and individual risk factors for triangulation: Evaluating evidence for emotion coaching buffering effects. Family Process, 61(2), 841–857. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12703

McMorris, T., & Hale, T. S. (2006). Coaching science: Theory into practice. John Wiley & Sons.

Mesquita, B. (2001). Emotions in collectivist and individualist contexts. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 80(1), 68–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.80.1.68

Mitchell, A. E., Dickens, G. L., & Picchioni, M. (2014). Facial Emotion Processing in Borderline Personality Disorder: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 24(2), 166–184. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-014-9254-9

Nemeth, N., Matrai, P., Hegyi, P., Czeh, B., Czopf, L., Hussain, A., ... & Simon, M. (2018). Theory of mind disturbances in borderline personality disorder: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Research, 270, 143–153. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.08.049

Netzer, L., Van Kleef, G. A., & Tamir, M. (2015). Interpersonal instrumental emotion regulation. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 58, 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.01.006

Niven, K. (2017). The four key characteristics of interpersonal emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 17, 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.06.015

Niven, K., Totterdell, P., & Holman, D. (2009). A classification of controlled interpersonal affect regulation strategies. Emotion, 9(4), 498–509. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015962

Niven, K., Macdonald, I. A., & Holman, D. (2012). You spin me right round: Cross-Relationship Variability in interpersonal emotion regulation. Frontiers in Psychology, 3. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00394

Nozaki, Y., & Mikolajczak, M. (2020). Extrinsic emotion regulation. Emotion, 20(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000636

Osterhaus, C., & Koerber, S. (2021). The Development of Advanced Theory of Mind in Middle Childhood: A longitudinal study from age 5 to 10 years. Child Development, 92(5), 1872–1888. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13627

Overall, N. C., Fletcher, G. J., Simpson, J. A., & Sibley, C. G. (2009). Regulating partners in intimate relationships: The costs and benefits of different communication strategies. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 96(3), 620–639. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012961

Papera, M., Richards, A., Van Geert, P., & Valentini, C. (2019). Development of second-order theory of mind: Assessment of environmental influences using a dynamic system approach. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 43(3), 245–254. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025418824052

Patterson, E. A., Branch, S., Barker, M., & Ramsay, S. G. (2018). Playing with power. Qualitative Research in Organizations and Management: An International Journal, 13(1), 32–52. https://doi.org/10.1108/qrom-10-2016-1441

Peyton, P. R. (2004). Dignity at Work: Eliminate Bullying and Create and a Positive Working Environment. Routledge.

Pons, F., Lawson, J., Harris, P. L., & De Rosnay, M. (2003). Individual differences in children’s emotion understanding: Effects of age and language. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 44(4), 347–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9450.00354

Pop, R., Săplăcan, Z., Dabija, D., & Alt, M. (2021). The impact of social media influencers on travel decisions: The role of trust in consumer decision journey. Current Issues in Tourism, 25(5), 823–843. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2021.1895729

Porter, B., & López-Angulo, Y. (2022). Violencia vicaria en el contexto de la violencia de género: Un estudio descriptivo en Iberoamérica [Vicarious violence in the ontext of gender-based violence: A descriptive study in Ibero-America]. CienciAmérica, 11(1), 11–42.

Ramsay, S. G., Troth, A. C., & Branch, S. (2010). Work-place bullying: A group processes framework. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 84(4), 799–816. https://doi.org/10.1348/2044-8325.002000

Reeck, C., Ames, D. R., & Ochsner, K. N. (2016). The Social Regulation of Emotion: An Integrative, Cross-Disciplinary model. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 20(1), 47–63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.09.003

Rimé, B., Páez, D., Basabe, N., & Martínez, F. J. S. (2009). Social sharing of emotion, post-traumatic growth, and emotional climate: Follow-up of Spanish citizen’s response to the collective trauma of March 11th terrorist attacks in Madrid. European Journal of Social Psychology, 40(6), 1029–1045. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.700

Rimé, B., Bouchat, P., Paquot, L., & Giglio, L. (2020). Intrapersonal, interpersonal, and social outcomes of the social sharing of emotion. Current Opinion in Psychology, 31, 127–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.08.024

Robins, G. (2011). Exponential Random Graph Models for Social Networks. In J. Scott & P. Carrington (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis (pp. 484–500). Sage Publications.

Robinson, S. L., & Schabram, K. (2019). Workplace ostracism: What’s it good for? In S. C. Rudert, R. Greifeneder, & K. D. Williams (Eds.), Current directions in ostracism, social exclusion, and rejection research (pp. 155–170). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351255912-10

Rump, K., Giovannelli, J., Minshew, N. J., & Strauss, M. (2009). The development of emotion recognition in individuals with autism. Child Development, 80(5), 1434–1447. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01343.x

Sabbagh, M. A. (2004). Understanding orbitofrontal contributions to theory-of-mind reasoning: Implications for autism. Brain and Cognition, 55(1), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandc.2003.04.002

Schotter, A., Zheng, W., & Snyder, B. (2000). Bargaining through Agents: An experimental study of delegation and commitment. Games and Economic Behavior, 30(2), 248–292. https://doi.org/10.1006/game.1999.0728

Schuster, M. A., Stein, B. D., Jaycox, L. H., Collins, R. L., Marshall, G. N., Elliott, M. N., Zhou, A. J., Kanouse, D. E., Morrison, J. L., & Berry, S. H. (2001). A National Survey of Stress Reactions after the September 11, 2001, Terrorist Attacks. The New England Journal of Medicine, 345(20), 1507–1512. https://doi.org/10.1056/nejm200111153452024

Sibley, M. H., Evans, S. W., & Serpell, Z. (2009). Social Cognition and Interpersonal Impairment in Young Adolescents with ADHD. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 32(2), 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-009-9152-2

Smyth, J. M., & Heron, K. E. (2013). Ecological Momentary Assessment (EMA) in family research. In National symposium on family issues (pp. 145–161). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-01562-0_9

Southward, M. W., Altenburger, E. M., Moss, S., Cregg, D. R., & Cheavens, J. S. (2018). Flexible, yet firm: A model of healthy emotion regulation. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 37(4), 231–251. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2018.37.4.231

Sutton, J., Smith, P. K., & Swettenham, J. (1999). Bullying and ‘Theory of Mind’: A critique of the ‘Social Skills Deficit’ view of Anti-Social behaviour. Social Development, 8(1), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9507.00083

Tamir, M. (2015). Why do people regulate their emotions? A taxonomy of motives in emotion regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 20(3), 199–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868315586325

Tanna, V. J., & MacCann, C. (2023). I know you so I will regulate you: Closeness but not target’s emotion type affects all stages of extrinsic emotion regulation. Emotion, 23(5), 1501–1505. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001073

Travis, L. L., & Sigman, M. (1998). Social deficits and interpersonal relationships in autism. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 4(2), 65–72. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-2779(1998)4:2%3c65::AID-MRDD2%3e3.0.CO;2-W

van Kleef, G. A., Cheshin, A., Koning, L., & Wolf, S. (2019). Emotional games: How coaches’ emotional expressions shape players’ emotions, inferences, and team performance. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 41, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2018.11.004

Wang, J., Yang, J., Yang, Z., Gao, W., Zhang, H., Ji, K., Klugah-Brown, B., Yuan, J., & Biswal, B. B. (2023). Boosting interpersonal emotion regulation through facial imitation: Functional neuroimaging foundations. Cerebral Cortex. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhad402

Watson, A., Nixon, C. L., Wilson, A., & Capage, L. (1999). Social interaction skills and theory of mind in young children. Developmental Psychology, 35(2), 386–391. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.35.2.386

West, S. G., Friedman, S. H., & Resnick, P. J. (2009). Fathers Who Kill Their Children: An Analysis of the literature. Journal of Forensic Sciences, 54(2), 463–468. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1556-4029.2008.00964.x

Westby, C., & Robinson, L. (2014). A developmental perspective for promoting theory of mind. Topics in Language Disorders, 34(4), 362–382. https://doi.org/10.1097/tld.0000000000000035

Widmer, E. D. (2016). Family configurations: A structural approach to family diversity. Routledge.

Wilczynski, A. (1995). Risk Factors for Parental Child HomicideResults of an English Study. Current Issues in Criminal Justice, 7(2), 193–222. https://doi.org/10.1080/10345329.1995.12036696

Zaki, J. (2020). Integrating empathy and interpersonal emotion regulation. Annual Review of Psychology, 71(1), 517–540. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-050830

Zaki, J., & Williams, W. C. (2013). Interpersonal emotion regulation. Emotion, 13(5), 803–810. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033839

Zaki, J., Bolger, N., & Ochsner, K. N. (2008). It takes two. Psychological Science, 19(4), 399–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2008.02099.x

Zuffianò, A., Vilar, M. M., & López-Pérez, B. (2018). Prosociality and life satisfaction: A daily-diary investigation among Spanish university students. Personality and Individual Differences, 123, 17–20. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.10.042

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Conflicting interests

The authors declare there is no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions